Abstract

Introduction

Oral antidiabetes medications, including dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4is) saxagliptin and sitagliptin, are used for the treatment of type 2 diabetes (T2D). The study objective was to compare all-cause and diabetes-related costs following initiation of saxagliptin or sitagliptin.

Methods

Patients aged ≥18 years initiating saxagliptin or sitagliptin between January 1, 2009 and January 31, 2012 in the Truven Health MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental databases were identified. Patients were required to have continuous enrollment for ≥365 days before and ≥365 days after the index date (date of the first saxagliptin or sitagliptin claim). Additionally, patients were required to have a claim with a T2D diagnosis (ICD-9-CM 250.×0, 250.×2) and no claims for a DPP-4i medication before the index date. All-cause and diabetes-related medical costs and total costs (including pharmacy costs) were captured over the 1-year follow-up period. Generalized linear models with log link and gamma distribution were fit to compare costs between the two cohorts using cost ratios, controlling for patient baseline characteristics. Recycled prediction methods were used to generate adjusted predicted costs and confidence intervals.

Results

The final sample comprised 3354 saxagliptin initiators and 26,895 sitagliptin initiators. The average age of saxagliptin and sitagliptin initiators was 57 years and just over 50% were males. After adjusting for baseline characteristics, saxagliptin patients had significantly lower average all-cause medical costs (cost ratio = 0.901, P < 0.001; predicted mean costs: $8687 vs. $9646) compared with sitagliptin patients over the 1-year follow-up. Findings were consistent for diabetes-related medical costs (cost ratio = 0.890, P < 0.001; predicted mean costs: $2180 vs. $2450). Total costs were also lower for saxagliptin initiators (cost ratio = 0.950, P = 0.002; predicted mean costs: $13,911 vs. $14,651) over the 1-year follow-up period.

Conclusion

Initiation of treatment with saxagliptin was associated with lower medical costs over 1 year compared with initiation of sitagliptin among adults with T2D.

Funding

AstraZeneca.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The American Diabetes Association reports that between 2007 and 2012, the total cost of diabetes in the United States increased 41% from $174 billion (2007 USD) to $245 billion (2012 USD) [1]. Direct medical costs accounted for $176 billion [1]. The primary components of the costs were direct medical costs for inpatient care, prescription medications to treat diabetes-related complications, and antidiabetes therapies and supplies, responsible for 43%, 18%, and 12% of the $176 billion sum, respectively [1]. An additional $69 billion was attributed to lost productivity [1]. Compared with individuals without diabetes, patients diagnosed with diabetes have 2.3 times greater healthcare costs, averaging $13,741 annually compared with $5853 [1]. Therefore, an estimated $7888 in excess costs per year per person may be associated with diabetes [1].

For patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D), the primary goal of treatment is to achieve and maintain glycemic control [2], as poor glycemic control is associated with numerous microvascular and macrovascular complications including, but not limited to, diabetic nephropathy, retinopathy, coronary artery disease, and stroke [3]. For patients with T2D, standards of care recommend metformin first for appropriate patients in combination with dietary and lifestyle modifications, and if treatment failure occurs, the addition of a supplementary non-insulin agent such as a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA), sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor (SGLT-2i), dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor (DPP-4i), thiazolidinedione (TZD), sulfonylurea (SU), or meglitinide (GLN) [2–4].

In the United States, two commonly used DPP-4i medications are saxagliptin and sitagliptin. Compared with patients who initiated sitagliptin, saxagliptin initiators have been found to have better medication adherence and persistence [5]. Additionally, saxagliptin initiators were reported to have lower all-cause and diabetes-related medical costs over the 6 months following initiation [6]. Direct cost comparisons between patients treated with one of these two DPP-4i medications over longer periods of time are not available. This retrospective claims-based study sought to add to the body of available evidence by comparing the healthcare utilization and costs among patients with T2D who initiated saxagliptin to those who initiated sitagliptin in the 12 months following initiation.

Methods

Study Design

This retrospective observational cohort study used administrative claims data to analyze the all-cause and diabetes-related healthcare resource utilization and costs for patients with T2D who initiated saxagliptin or sitagliptin between January 1, 2009, and January 31, 2012. The patients included in this analysis were a subset of a previously identified sample of patients with T2D [5]. Among these patients, healthcare resource utilization and costs were compared among saxagliptin initiators and sitagliptin initiators over the 12 months following DPP-4i initiation.

Data Sources

Two Truven Health MarketScan® research databases were used in this study: the Commercial Claims and Encounters Database (Commercial) and the Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits Database (Medicare Supplemental). The Commercial database contains the inpatient and outpatient medical and outpatient prescription drug experience of several million lives annually. The Medicare Supplemental database contains the healthcare experience (both medical and pharmacy) of individuals with Medicare supplemental insurance paid for by employers. Both databases provide detailed cost, use, and outcomes data for healthcare services performed in both inpatient and outpatient settings across a variety of fee-for-service, fully capitated, and partially capitated health plans. The health plans include preferred provider organizations, point of service plans, indemnity plans, and health maintenance organizations. The medical claims are linked to outpatient prescription drug claims and person-level enrollment data through the use of unique enrollee identifiers.

Inclusion Criteria

The Commercial and Medicare Supplemental databases were used to identify adults (age ≥18 years) with at least one prescription for saxagliptin or sitagliptin during the period extending from January 1, 2009 to January 31, 2012. The service date on the first observed prescription for saxagliptin or sitagliptin was defined as the index date and the drug filled on the index date was designated the index drug. Patients were required to have at least 28 days of continuous days supplied of the index drug to qualify for the study. Additionally, patients were required to have continuous medical and pharmacy benefits enrollment for at least 12 months prior to and following the index date. Patients were required to have a medical claim with a diagnosis of T2D (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code 250.×0 or 250.×2); however, patients were excluded if they had a prescription for a DPP4-i medication in the year prior to index or a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes mellitus (ICD-9-CM code 250.×1 or 250.×3) or gestational diabetes (ICD-9-CM code 648.8×) on a medical claim at any time during the study period. Patients were allowed to have prescription claims for other antidiabetes medications prior to the index date. These patient selection criteria have been published previously [5]. Patients were stratified into two cohorts based on index drug: saxagliptin initiators or sitagliptin initiators. This was an intent-to-treat analysis.

Outcomes

Healthcare utilization and costs were measured during the 12 months following the index date (follow-up period). Both all-cause and diabetes-related resource utilization and costs were captured. Diabetes-related measures were defined as medical claims with a primary or non-primary diagnosis of T2D (ICD-9-CM 250.×0, 250.×2) or an outpatient claim for an antidiabetes medication. The following service categories were captured: inpatient admissions, emergency room (ER) visits, outpatient physician office visits, other outpatient services (including laboratory and radiology services, ambulatory care, dialysis, etc.), which were all considered medical costs, and outpatient pharmacy fills. Pharmacy fills for index drug (saxagliptin or sitagliptin) were also captured. Costs were the paid amount on claims, including insurer- and patient-paid portions. Medical, pharmacy, and total costs (the sum of medical and pharmacy costs) were adjusted to 2013 US dollars using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index [7], as the 12 months of follow-up extended into 2013 for some patients. Costs for capitated claims were imputed using a payment proxy based on the payment of non-capitated claims with the same procedure code in the same year, from the region. The primary outcomes of interest were all-cause and diabetes-related medical costs, all-cause and diabetes-related pharmacy costs, and total all-cause and diabetes-related healthcare costs. Secondary outcomes were presence of all-cause and diabetes-related inpatient admissions and inpatient costs, all-cause and diabetes-related other outpatient medical costs, and index drug (saxagliptin or sitagliptin) pharmacy costs, as these were the main drivers of costs in this population.

As adherence and persistence to medications may be associated with higher diabetes-related pharmacy costs and lower diabetes-related medical costs, adherence to and persistence with saxagliptin and sitagliptin over the 12-month follow-up period was also measured. Proportion of days covered (PDC) was used to measure adherence. PDC was calculated by dividing the number of days the patient was covered on index drug during the 12-month follow-up period by 365 days. If there was an overlap in index drug, the overlapping days supply was appended to the previous prescription’s end. Patients with PDC ≥0.80 were considered adherent. Discontinuation of the initiated drug was also evaluated. Patients were followed starting with their index prescription and were considered to have ‘discontinued’ if they had a gap of more than 60 days without any drug supply available during the 12-month follow-up.

Covariates

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics were captured. Demographic characteristics were measured at index date and included age, gender, geographic region, insurance plan type, and index year. Use of other antidiabetes medications, including insulin, was captured during the 12 months prior to the index date based on pharmacy claims. Comorbid conditions based on diagnosis and procedure codes on medical claims, and healthcare costs were also measured during this period. Index drug was classified as mail order or non-mail order. Cost sharing for the index drug, defined as the average patient out-of-pocket cost for a 30-day supply on index drug for patients in each insurance plan, was also calculated [8]. Lastly, claims for non-DPP-4i antidiabetes medications filled around the time of the index date were evaluated to determine if a patient was using any other classes of antidiabetes medications in combination with saxagliptin or sitagliptin. Based on these claims, a patient’s ‘index regimen’ was determined and classified as polytherapy or monotherapy. Patients were considered to be on polytherapy if they had (A) one pharmacy claim in the 60 days prior to the index date and a second pharmacy claim in the 45 days following index for a non-DPP-4i drug; (B) had a pharmacy claim for a non-DPP-4i drug during the time window index date −60 days to index date +45 days that overlapped with index drug for at least 30 days in the first 45 days following index date; or (C) indexed on a fixed-dose metformin combination drug [5]. All other patients were considered to be on a monotherapy regimen [5]. A full list of study covariates is included in Table 1.

Statistical Analyses

Demographic, clinical, treatment regimen characteristics, and outcomes (Tables 1, 2, 3) were compared between the saxagliptin and sitagliptin cohorts using t tests for continuous variables and Chi-squared tests for categorical variables. Multivariable generalized linear models (GLMs) with a log link and gamma error distribution were used to compare costs among patients initiating saxagliptin and sitagliptin. A log link and gamma error distribution were used to handle the non-normal cost distributions. If the P value for the cost ratio of the cohort coefficient from the model was <0.05, the difference between the saxagliptin and sitagliptin cohorts was considered statistically significant. To present adjusted costs on the dollar scale, the recycled prediction method was used to generate predicted mean costs. In the recycled prediction method, mean costs are calculated for two pseudo-samples (one saxagliptin and one sitagliptin), the size of both pseudo-samples being the total number of patients. Each pseudo-sample is a combination of observed values for those patients who had the treatment concerned and predicted counterfactuals for those patients who had the other treatment.

Although the same methods of GLMs with log link and gamma error distribution, followed by use of the recycled prediction method to calculate adjusted costs on the dollar scale, were used to analyze all cost variables in separate models, the actual process followed was different for the inpatient cost variables and the others, i.e., total, medical, other outpatient medical and pharmacy costs. The reason for this difference is that a high percentage (approximately 90%) of inpatient costs were zero, i.e., the patient had no such costs, whereas for the other cost variables, hardly any patients had zero costs.

Therefore, for the inpatient costs only, a two-part modeling approach was used to estimate predicted probability of all-cause and diabetes-related inpatient admission and inpatient costs to account for patients with $0. First, logistic regression models were fit to model the odds of inpatient admission and the estimates of coefficients from these models were used to generate predicted probabilities of inpatient admission. Second, GLMs with log link and gamma error distribution were fit to obtain predicted inpatient costs among patients with non-zero costs. To obtain average inpatient costs for each cohort, the predicted probability of inpatient admission was multiplied by the predicted costs. Bootstrapping, using 1000 resamples of the observed data, was used to generate 95% confidence intervals around probability of inpatient admission and average inpatient costs, these estimates of intervals and averages being taken from the bootstrapping distributions of the 1000 resamples.

For total, medical, other outpatient medical and pharmacy costs, only the GLMs with log link and gamma error distribution were fit (essentially discarding patients with zero costs), and bootstrapping was not used. The recycled prediction estimate of cost on the dollar scale for these outcomes was from the single analysis of the observed data. For these costs, the estimates of averages and 95% confidence intervals for costs on the dollar scale were from the distributions of the two pseudo-samples.

All aforementioned models controlled the following variables: age, sex, presence of capitated services, payer, region, population density (metro vs. non-metro), plan type, index year, indicator for fixed-dose metformin index drug, indicator for index drug filled via mail order, index regimen (monotherapy, index drug plus additional non-insulin antidiabetic drugs [NIAD], index drug plus insulin), baseline total healthcare costs and diabetes prescription expenditures, index diabetes medication class cost sharing, baseline endocrinologist and cardiologist visits, baseline renal impairment, baseline macrovascular and microvascular disease, pregnancy during follow-up, baseline number of unique 3-digit ICD-9 diagnoses and Deyo Charlson Comorbidity Index [9]. Variables included were hypothesized to be potential confounders of the relationship between the type of drug initiated and post-initiation costs, as this was an observational analysis and patients were not randomly assigned to receive saxagliptin or sitagliptin. The covariates listed above are demographic characteristics and clinical characteristics, including proxies for severity of diabetes, which may affect a clinician’s choice of medication and may also affect costs. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., SAS Campus Drive, Cary, NC, USA).

Compliance with Ethic Guidelines

The analyses presented are based on previously collected, de-identified data, and do not contain any new studies with human subjects performed by any of the authors.

Results

Patient Demographics

There were 30,249 DPP-4i initiators who met the study criteria and among them, 3354 initiated saxagliptin (11.1%). Demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. On average, patients were approximately 57 years old and slightly more than half were male, with no significant differences between saxagliptin and sitagliptin initiators. A significantly larger proportion of saxagliptin initiators resided in the South. The majority of patients insured through a commercial plan (approximately 78%) and a significantly smaller proportion of saxagliptin initiators had evidence of capitated services.

Clinical Characteristics and Index Regimen Characteristics

Clinical characteristics and index regimen characteristics are also presented in Table 1. During the baseline period, 6.5%, 12.7%, and 21.3% of study patients had evidence of renal impairment, microvascular disease (as evidenced by diabetic peripheral neuropathy, diabetic retinopathy, leg and foot amputation, or nephropathy), and macrovascular disease (characterized by evidence of acute myocardial infarction, other ischemic heart disease, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular accident, or peripheral vascular disease), respectively, with no significant differences between the two cohorts. Overall, however, saxagliptin patients had a significantly greater number of unique ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes prior to the index date. A significantly larger proportion of saxagliptin initiators used metformin during the baseline period. There were no significant differences in total healthcare costs or diabetes medication costs during the baseline period, although total healthcare costs tended to be lower for saxagliptin initiators, on average. Regarding index regimen, a significantly smaller proportion of saxagliptin initiators had an index prescription that was a fixed-dose combination with metformin. Initiating monotherapy was significantly more common among saxagliptin initiators.

Healthcare Resource Utilization and Costs

Saxagliptin initiators tended to have lower unadjusted all-cause and diabetes-related medical costs than sitagliptin initiators in all service categories but most of the cost comparisons were not statistically significant (Table 2). Average outpatient pharmacy prescription costs were significantly higher for saxagliptin initiators. Healthcare utilization was similar between the two cohorts, although the proportion of patients with an all-cause inpatient admission was significantly smaller in the saxagliptin cohort.

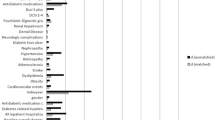

Results from multivariable models controlling for covariates and predicted costs are presented in Fig. 1. Over the 12 months following initiation, saxagliptin patients had 9.9% lower all-cause medical costs and 11.0% lower diabetes-related medical costs than patients who initiated sitagliptin. Differences in predicted mean all-cause medical and diabetes-related medical costs between the two cohorts were $959 and $270, respectively, favoring saxagliptin. Additionally, all-cause and diabetes-related total costs were both approximately 5.0% lower in saxagliptin patients. Pharmacy costs, however, were higher among saxagliptin initiators with a difference in predicted mean all-cause costs of $207, and difference in predicted mean diabetes-related cost of $51. When evaluating saxagliptin and sitagliptin prescription costs for the two cohorts, the saxagliptin cohort tended to have higher costs but the difference was not statistically significant. Results for inpatient admission and costs are presented in Table S1 in the supplementary material. The predicted proportion of saxagliptin patients with an inpatient admission (11.0%) was significantly smaller than the predicted proportion of sitagliptin patients (12.5%, difference = 1.5%, 95% confidence interval −2.5%, −0.2%). There were no significant differences in predicted proportion of patients with a diabetes-related inpatient admission or predicted inpatients costs. Results for other outpatient medical costs models are presented in Table S2 in the supplementary material. Compared with sitagliptin patients, saxagliptin patients had significantly lower predicted all-cause other outpatient medical costs ($4834 vs. $5457) and predicted diabetes-related outpatient medical costs ($848 vs. $1093).

Adherence and Persistence to Initiated Medication during Follow-Up

As shown in Table 3, over the 12-month follow-up period, the proportion of patients who were adherent was significantly greater in the saxagliptin cohort compared with the sitagliptin cohort in an unadjusted analysis. Similarly, a smaller proportion of saxagliptin initiators discontinued index drug during follow-up. The average number of index drug prescription fills was significantly higher for the saxagliptin cohort compared with the sitagliptin cohort (Table 2).

Discussion

In this retrospective, observational claims-based analysis of adults with T2D, all-cause and diabetes-related medical costs were lower among saxagliptin initiators compared with sitagliptin initiators over a 12-month follow-up period. Additionally, total all-cause and diabetes-related healthcare costs were also lower in saxagliptin patients, although the magnitudes of the differences were smaller due to the tendency of saxagliptin patients to have greater pharmacy costs. Presently, there is very little information available directly comparing real-world costs and healthcare resource utilization among saxagliptin and sitagliptin initiators. To our knowledge, this is the first analysis to compare costs and utilizations among patients initiating one of the DPP-4i medications over a 12-month follow-up period.

Potential explanations for lower costs observed in saxagliptin patients in this study include a lower proportion of patients with inpatient admissions among saxagliptin initiators (11.1% saxagliptin vs. 12.5% sitagliptin) as well as better adherence and persistence to the index drug among saxagliptin initiators. Saxagliptin patients were more adherent over the 12-month follow-up (50.7% saxagliptin vs. 47.4% sitagliptin) and had decreased odds of all-cause inpatient admission. Previous research has found that within the DPP-4i medication class, patients initiating saxagliptin had better adherence and persistence than patients who initiated sitagliptin [5]. Increasing adherence to antidiabetes medication has been correlated with increased glycemic control and decreased healthcare costs and resource utilization [10–12].

A previous investigation by Kaltenboeck et al. [6] evaluated healthcare costs and utilization over 6 months following the initiation of saxagliptin, sitagliptin, or SU. Only unadjusted utilization results were presented [6]. Over the short follow-up period, significantly smaller proportions of saxagliptin initiators had an all-cause inpatient admission or an ER visit compared with sitagliptin initiators (7.2% vs. 10.6% and 14.1% vs. 17.5%, respectively) [6]. The same was true for diabetes-related inpatient admissions (4.0% vs. 6.6%) and diabetes-related ER visits (5.7% vs. 7.3%) [6]. The saxagliptin cohort had a significantly greater proportion of patients with a diabetes-related outpatient visit (80.2% vs. 78.6%) [6]. Unadjusted mean all-cause and diabetes-related total costs were significantly lower for saxagliptin initiators than sitagliptin initiators ($7346 vs. $8797 and $2445 vs. $2828, respectively) [6]. Mean costs were significantly lower for all service categories except diabetes-related outpatient visits and diabetes-related prescription costs, although saxagliptin initiators tended to have lower costs for both [6]. The findings after adjusting for patient demographic and clinical characteristics were consistent [6]. Saxagliptin patients had significantly lower all-cause medical ($5073 vs. $5535, P < 0.001) and total costs ($7802 vs. $8302, P < 0.001) [6]. Additionally, compared with sitagliptin patients, saxagliptin patients had significantly lower diabetes-related medical ($1149 vs. $1387, P < 0.001) and total costs ($2510 vs. $2772, P < 0.001) [6].

This study has several limitations to acknowledge. First, administrative claims data are not collected for research purposes, as the diagnostic coding on administrative claims is recorded by physicians to support reimbursement. Diagnoses on claims may be coded incorrectly, or not at all, thereby potentially introducing measurement error with respect to variables that incorporated ICD-9-CM codes into their definitions. Similarly, prescriptions that were filled and did not generate an insurance claim were not captured in this analysis. Adherence and persistence were calculated using the service date and days supply information found on outpatient prescription drug claims and while it is assumed that the medication was taken as directed, skipped doses or discontinuation of the medication before the end of the current days supply could not be captured. Next, observational analyses may be subject to residual confounding even after multivariable adjustment, and causal inferences should be made cautiously. Lastly, study findings may not be generalizable to the entire Medicare population, Medicaid population, or uninsured population as the MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental databases contain data only on patients receiving coverage through employers, private commercial insurance, or employer-sponsored supplemental Medicare.

Conclusions

For adults with T2D, initiation of treatment with saxagliptin was associated with lower all-cause and diabetes-related medical costs over 1 year compared with sitagliptin. The differences in costs may be due in part to better adherence and fewer hospitalizations among saxagliptin initiators.

References

American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2012. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(4):1033–46.

American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes–2014. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(Suppl 1):S14–80.

Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach. Position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia. 2012;55(6):1577–96.

Handelsman Y, Bloomgarden Z, Grunberger G, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology—Clinical Practice Guidelines for Developing a Diabetes Mellitus Comprehensive Care Plan—2015. Endocr Pract. 2015;21:1–87.

Farr AM, Sheehan JJ, Curkendall SM, Smith DM, Johnston SS, Kalsekar I. Retrospective analysis of long-term adherence to and persistence with DPP-4 inhibitors in US adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Adv Ther. 2014;31(12):1287–305.

Kaltenboeck A, Ivanova J, Birnbaum H, et al. Costs after initiating saxagliptin, sulfonylurea, or sitagliptin in patients with T2DM. Am J Pharm Benefits. 2014;6(3):e60–9.

Consumer Price Index Detailed Report Tables Annual Average 2013. Accessed at: http://www.bls.gov/cpi/tables.htm. Accessed March 9, 2015.

Gibson TB, Song X, Alemayehu B, et al. Cost sharing, adherence, and health outcomes in patients with diabetes. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(8):589–600.

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–9.

Asche C, LaFleur J, Conner C. A review of diabetes treatment adherence and the association with clinical and economic outcomes. Clin Ther. 2011;33(1):74–109.

Wild H. The economic rationale for adherence in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(3 Suppl):S43–8.

Salas M, Hughes D, Zuluaga A, Vardeva K, Lebmeier M. Costs of medication nonadherence in patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and critical analysis of the literature. Value Health. 2009;12(6):915–22.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by AstraZeneca. The article processing charges and open access fee for this publication were funded by AstraZeneca. Parts of this manuscript were presented as a podium presentation at the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research 20th Annual International Meeting in Philadelphia, PA, USA. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published.

Disclosures

A. M. Farr, M. Brouillette, D. M. Smith, and S. S. Johnston are employees of Truven Health Analytics and have nothing to disclose. J. J. Sheehan is a current employee of AstraZeneca. I. Kalsekar is a former employee of AstraZeneca.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

The analyses presented are based on previously collected, de-identified data, and do not contain any new studies with human subjects performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Farr, A.M., Sheehan, J.J., Brouillette, M. et al. Healthcare Costs Among Adults with Type 2 Diabetes Initiating DPP-4 Inhibitors. Adv Ther 33, 68–81 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-015-0277-2

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-015-0277-2