Abstract

Using a nationally representative dataset, this study analyzes: 1) 12th grade trends, patterns, and changes in bullying victimization in the United States from the 1989 to the 2009 school years, and 2) the differential impacts of demographic, social, and economic characteristics on bullying victimization. Four self-reported experiences of bullying behavior that occurred at school or in transit to and from school are studied: threatened without a weapon, threatened with a weapon, injured without a weapon, and injured with a weapon. Zero-inflated Poisson models are used to estimate intensity (or rate) and likelihood of exposure (or probability) parameters of the annual frequency distributions of the four bullying behaviors. For the intensity of bullying victimization, as measured by the average number of times 12th graders were bullied annually, it is found, first, that there indeed was a wave of increased bullying behaviors in the 2002–2009 years that coincides with increased media attention and reporting during these years. Second, it is shown that this recent upsurge is similar to what happened in the early 1990s—but the most recent wave reached higher levels of intensity. Third, the analyses reveal that the intensity and/or exposure parameters covary with several demographic, socioeconomic, and behavioral factors and these differentials persist over time. While 12th graders who were male or African American, city dwellers, and from single-parent or no-parent families show persistently higher intensities of bullying victimization over time, greater probabilities of exposure are found for 12th graders who were male, were from single-parent or no- parent families, did not regularly attend religious services, regarded religion as less important, and showed worse school performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Propelled by concerns about school violence and a public outcry following highly publicized bully-related suicides, child and youth bullying behaviors, especially in school contexts, have received increased attention during the past few years from the press, policy makers, and school administrators in the United States (Benbenishty and Astor 2005; Berger 2007; Srabstein 2008). While the psychological trauma caused by school bullying is so overwhelming that some students being bullied at school may believe that suicide is the only solution, school bullying can also leave long-lasting psychological and emotional scars such that the former victims tend to be depressed and show lower self-esteem even after leaving school (Olweus 1994; Smith and Myron-Wilson 1998). Moreover, school bullying, especially in the form of direct attacks and physical harassment, can foster an unpleasant and intimidating school environment affecting victims, bystanders, and fellow students (Bosworth et al. 1999). For instance, about 10 % of high school dropouts identified fear of being attacked or harassed as their most important reason for not returning to school (Greenbaum et al. 1989).

Although a violence-free learning environment was included as one of the six National Education Goals in the United States in the 1990s, increases in the prevalence of school bullying were reported in the early 2000s (National Education Goals Panel 1993; Srabstein 2008; Duncan 2010). While increased school bullying was labeled by policy makers as an epidemic, it has been argued that current anti-bullying efforts nationwide not only fail to change the status quo but may lead to an increase in school bullying (Hu 2011; Duncan 2010). Without concrete evidence about historical trends in school bullying and changes in bullying victimization across demographic, social and economic groups, the wisdom behind the war against school bullying will continue to be challenged. Important questions remain as to whether the recent increase in school bullying is unique, what are the relative risks of bully victimization of students with different socio-demographic and behavioral characteristics, and how the influence of these risk factors varies over time. Yet a paucity of research on the trends of school bullying has been conducted, and virtually no studies in the US have examined socio-economic disparities in school bullying over time.

To address these questions, this research uses a nationally representative dataset of 12th graders to analyze trends and changes in school bullying and in the differential exposure of demographic, social, and economic groups to school bullying. The next section commences with a review of the literature on definitions and the trends of bullying victimization across demographic, social, and economic groups. After a brief description of data and variables used in this study, the rational for using zero-inflated Poisson models and their statistical details is presented. Guided by findings from existing literature, an empirical analysis of both exposure and intensity of bullying victimization over time then reveals the overall trends and disadvantage/advantage of certain groups. Finally, this article concludes with a discussion of possible explanations of findings.

2 Research on Bullying

2.1 The Definition of Bullying Victimization

The definition of bullying victimization proposed by Olweus (1994: 1173) has frequently been used to guide empirical studies: “a student is being bullied or victimized when he or she is exposed, repeatedly and over time, to negative actions on the part of one or more other students.” Granted that negative actions can be in the forms of physical attacks, name-calling and more subtle ways such as social isolation, direct bullying involving open attacks and threats on a victim features the imbalance of power and aggressive nature of school bullying, which may lead to more detrimental outcomes (Olweus 1991, 1994; Rigby 2002; Nansel et al. 2003). If school bullying is regarded as longstanding violence or harassment directed against an individual who has difficulty in defending himself/herself, we would expect that the systematic abuse of power has persistent effects on individuals who possess few resources and skills to escape school bullying (Roland 1989; Smith and Sharp 1994). Prior research on patterns, trends, and changes in bullying behaviors is limited, and, thus does not reveal the macro-social dynamics of bullying behaviors. If the trends and changes of bullying victimization actually mirror more fundamental social changes in the US such as decreased social capital, increased social isolation, breakup of families, teenage births, and the more recent economic meltdown, a study using a coherent set of variables on the trends and patterns of differential bullying behaviors is needed.

2.2 Demographic Differentials in Bullying Victimization

It has been widely observed that boys are more likely to be exposed to school bullying than girls across national studies (Olweus 1994; Nansel et al. 2001; Bosworth et al. 1999; Espelage and Swearer 2003; Schwartz et al. 2002). In particular, physical and direct bullying behaviors tend to be more prevalent among boys, which is in tandem with gender disparities in aggressive behaviors worldwide (Ekblad and Olweus 1986; Maccoby and Jacklin 1980; Olweus 1994). Regarding the prevalence of bullying across race/ethnicity groups, a large-scale study found that compared with whites and Latinos, more Black youth in the US report being bullied and the association is statistically significant (Nansel et al. 2001). Likewise, African Americans in urban middle schools tended to be identified by fellow students as aggressive (Graham and Juvonen 2002).

2.3 Bullying Victimization and Socio-economic Status

Mixed findings have been reported regarding the association between bullying victimization and socio-economic status. A survey including over 6,000 respondents from 17 junior/middle schools in the United Kingdom showed a significant negative correlation between the frequency of bullying and socio-economic status of families, though the size of effect is small (Whitney and Smith 1993). A longitudinal study conducted in Finland suggested that parental education and socio-economic status were not associated with bullying victimization from childhood to adolescence (Sourander et al. 2000).

It has been found that children and youth from rural areas were more likely to be victims of bullying than their peers in urban areas. This is different from what one might expect based on studies of concentrated poverty and residential segregation in cities (Massey and Denton 1988; Wilson 1987). For example, Olweus (1991) found that the percentage of bullying victims was slightly lower in schools located in big cities compared with other parts of Norway. This finding was replicated by a study in the United Kingdom, which shows that victims of direct bullying were more likely to be students from rural schools (Woods and Wolke 2004).

Prior research indicates that children from single-parent or no-parent families are at greater risk of school bullying (Bowers et al. 1994; Smith and Myron-Wilson 1998). A study conducted in three middle schools in the UK found that bullying victims were less likely to report a father living at home and more likely to regard family members as distant (Bowers et al. 1994). Moreover, families of bullying victims tended to have insecure and negative parent–child interactions (Smith and Myron-Wilson 1998). In addition, aggressive behaviors of students were also found to be associated with negative parenting, such as punitive discipline, lack of warmth and failure to supervise children’s behaviors (Dishion 1990; Olweus 1980).

2.4 Bullying Victimization and Behavioral Characteristics

A negative association between academic performance and bullying victimization has been found in previous research, although the specific mechanism through which bullying victimization and school performance are associated remains unclear (Batsche and Knoff 1994). It was found that pupils (aged 10–12) with lower academic performance were more likely to be targets of school bullying in South Korea (Schwartz et al. 2002). In addition, intelligence is negatively associated with levels of bullying victimization for male students in primary schools (Perry et al. 1988).

Few studies specifically addressed the association between religion and bullying victimization. Given that frequent religious service attendance and strong religious orientation predict larger sizes of social network, more social support and better life satisfaction (Ellison and George 1994; Lim and Putnam 2010; Salsman et al. 2005), a negative association between religion and bullying victimization may exist if the latter correlates with social isolation and rejection (Schuster 1996). In this regard, it has been found that victims usually experience peer rejection and have very few friends at school for emotional support (Olweus 1994; Schuster 1999). Consequently, victims who show lower self-esteem and are disliked by peers may be trapped in a vicious cycle such that their withdrawal from school activities and social engagement is followed by more intensified school bullying (Batsche and Knoff 1994; Carney and Merrell 2001).

Based on these findings from prior research, it is expected that bullying victimization is more common and intense for students who are boys or African Americans, come from rural areas, live in single-parent or no-parent families, show lower academic performance, and weak religious identification. By examining the patterns, trends, and changes of bullying victimization of 12th graders in the US from 1989 to 2009, we test these hypotheses using zero-inflated Poisson models.

3 Data

This research is based on the Monitoring the Future (MTF) project, a nationally representative study designed to explore trends and changes in values, behaviors, and orientations of American adolescents. Since the MTF did not include annual surveys of 8th and 10th graders until 1991, our analysis of bullying victimization is based on MTF surveys of 12th graders (the last grade of school prior to receipt of a high school diploma) from 1989 to 2009. Instructed by MTF research staff, thousands of 12th graders annually participate in this survey by completing self-administered and machine-readable questionnaires at school. Participants respond to questions on a series of subjects, such as drug use, religious orientation, school performance, violence, and socio-economic status of their parents. In the present research, we focus on reports of bullying behaviors towards 12th graders. More than 44,000 12th graders were interviewed from 1989 to 2009. The information on experiencing bullying behavior is based on self-report data collected by the MTF. Because students involved in school bullying may feel uncomfortable or embarrassed describing school bullying to interviewers, researchers have concluded that self-reports are the best single data collection strategy for research on school bullying if the data collection has a clear definition of targeted behaviors, uses frequencies in response categories, and gives a delimited and natural time frame as the reference period (Bosworth et al. 1999; Olweus 1991).

3.1 Outcome Variables

Questions regarding school bullying during the last 12 months appear in the MTF questionnaire as follows. “The next questions are about some things which may have happened TO YOU while you were at school (inside or outside or in a school-bus). During the LAST 12 MONTHS, how often …”

-

1.

Has an unarmed person threatened you with injury, but not actually injured you?

-

2.

Has someone threatened you with a weapon, but not actually injured you?

-

3.

Has someone injured you on purpose without using a weapon?

-

4.

Has someone injured you with a weapon (like a knife, gun, or club)?

These specific targeted behaviors are hereinafter referred as threatened without injury, threatened with a weapon, injury without a weapon and injury with a weapon, respectively. Response categories for all four questions are measured by frequencies: 1) not at all, 2) once, 3) twice, 4) 3–4 times, and 5) 5+ times. Although the MTF also investigates a series of violence, misdemeanor, and criminal acts associated with respondents (e.g., hit an instructor or supervisor, take part of a car without permission of the owner, and damage school property on purpose), only these four questions are relevant to bullying victimization at school. For each of the four questions for each year from 1989 to 2009, the frequency distributions of the total samples of 12th graders were obtained from MTF codebooks.

Frequency distributions of specific socio-demographic and behavioral groups were retrieved and computed from each year’s MTF datasets for public use. To protect the confidentiality of respondents, certain variables were collapsed or recoded in the publicly released datasets but the difference between results generated by raw datasets and public-use datasets is below 1 % (Johnston et al. 1989). Annual relative frequency (percentage) distributions for the four outcome variables retrieved from public-use datasets are shown in Table 1.

3.2 Demographic, Socioeconomic, and Behavioral Covariates

Covariates that may affect the risk of bullying victimization identified in the review of prior research above are dichotomized to achieve greater statistical power. These dichotomized covariates include nine dummy variables denoting demographic background, socioeconomic status, and behavioral characteristics of 12th graders: sex (male vs. female), residential location (on a farm or in the country vs. in a city), family structure (single-parent and no-parent families vs. two-parent families), race (African American vs. non-African American), maternal education (tertiary education vs. secondary education and below), paternal education (tertiary education vs. secondary education and below), religious attendance (rare or no attendance vs. regular attendance), religious orientation (important vs. unimportant) and grade point average (GPA, B + and below vs. A- and above).Footnote 1 These covariates are chosen because their influence on school bullying has been documented or implied by existing literature. Table 2 presents the overall distributions of the covariates reported in this study. Due to relative small sample sizes of certain groups in particular years, data smoothing was applied to observed frequency distributions in order to facilitate the detection of temporal trends.

4 Statistical Models and Methods

Classic statistical models for analyzing rare events (such as school bullying) are built on the Poisson distribution (see, e.g., Fox 2008: 383; Long and Freese 2006: 394–396). The Poisson distribution has the restrictive property that its expected value (mean) and variance are equal. Empirical frequency distributions of rare events often do not satisfy this constraint, and, indeed, these distributions often have variances that exceed their means, i.e., they are over-dispersed. The source of over-dispersion in empirical frequency distributions often is an excess of observations with zero events, i.e., an excess of zeroes. Exploratory data analyses showed that this is the case for the MTF bullying count data shown in Table 1. In other words, more 12th graders are not at any risk of school-based bullying than would be expected if the bullying victimizations were distributed as Poisson variables.

To account for differential exposure to bullying behaviors, i.e., the possibility that bullying processes are not present in the school environments of some 12th graders, we estimated zero-inflated Poisson (ZIP) distributions with probability mass function given as follows (Lambert 1992):

where P is the proportion of 12th graders exposed to bullying behaviors and λ is the mean number of occurrences (average number of school bullying incidents) in a year for an individual among those exposed to the risk of school bullying. In brief, the ZIP model specifies a two-stage process for bullying victimization. In the first stage, the exposure to bullying is determined by a binomial distribution with the parameter P that estimates the likelihood that a 12th grader is exposed to bullying; in the second stage, the intensity or mean rate of bullying for students exposed to bullying is given by a Poisson distribution with expectation λ. As this approach is applied to different socio-demographic and behavioral groups, the extent of bullying victimization of a certain group is jointly determined by the likelihood of being bullied and the intensity of bullying given that individuals are at risk of being bullied. It should be noted that the exposure to bullying behaviors parameter of zero-inflated Poisson models P is not identical to observed prevalence rates (the proportion of students who report that they were bullied) in sample surveys because bullying behaviors may or may not happen to individuals who are at the risk of bullying victimization. Rather, observed prevalence rates experiencing an event in sample surveys are the sum of (1) the expected proportion of sample respondents who experience the event among those exposed to the event process for a specific Poisson rate parameter λ and (2) the proportion 1-P of the sample members who are in the latent class of individuals for whom the Poisson process is not operative and thus the outcome event count necessarily is zero. In brief, P is the proportion of the population surveyed who are members of the latent class of students at risk of the event being studied. In the present application, this is the latent class of 12th graders in a given school year for whom the specific violent bullying victimization response may be zero or a positive count, as estimated by the Poisson distribution with mean λ.

As already noted, the response categories for the reported numbers of bullying victimizations in the MTF data are combined (3–4 times) and right-censored (5 + times). No existing statistical software package can be readily applied to analyze such data. To overcome the computational challenge imposed by the data structure, an R program was written to estimate the parameters of the zero-inflated Poisson distributions over observed frequencies by minimizing mean absolute deviations in each year (Gelman and Hill 2007; Zeileis et al. 2008). There are no substantial differences in results when the weighted data of the MTF are used. Because frequency distributions reported by recent MTF codebooks are based on unweighted data, our analyses are unweighted.

5 Results

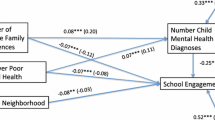

Findings on over-time trends and patterns in annual-sample estimates of the two parameters of the ZIP distributions for the four reported bullying behaviors are reported graphically in Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5. The values for the intensity trends are on the left horizontal axis. Overall, the estimated intensity of school bullying (λ) shows a marked increase from the late 1990s to early 2000s for being threatened without injury (Fig. 1a), threatened with a weapon (Fig. 1b), and injured without a weapon (Fig. 1c) and then slowed or declined beginning in the mid-2000s. For example, the intensity (λ) of school bullying through injury without a weapon (Fig. 1c) increased from 0.90 in 1989 to 1.08 in 2009, a 20 % increase during the period of study. The increases of intensity in the early 2000s were similar to, but more dramatic than, the increases that occurred in the early 1990s for these three bullying behaviors. The trend of intensity for being injured with a weapon (Fig. 1d) was high in the mid-1990s and again in the early 2000s, and also shows substantial increases since 2006.

Trends of estimated parameters of zero-inflated Poisson distributions, MTF data, 1989 to 2009, 12th graders. a Being Threatened without Injury: for 12th Graders, 1989–2009, b Being Threatened with a Weapon: for 12th Graders, 1989–2009, c Being Injured without a Weapon: for 12th Graders, 1989–2009, d Being Injured with a Weapon: for 12th Graders, 1989–2009

Trends of estimated parameters of zero-inflated Poisson distribution by sex, MTF, 1989 to 2009. a Being Threatened without Injury: for 12th Graders, 1989–2009, b Being Threatened with a Weapon: for 12th Graders, 1989–2009, c Being Injured without a Weapon: for 12th Graders, 1989–2009, d Being Injured with a Weapon: for 12th Graders, 1989–2009

Trends of estimated parameters of zero-inflated Poisson distributions by family parental composition, MTF, 1989 to 2009. a Being Threatened without Injury: for 12th Graders, 1989–2009, b Being Threatened with a Weapon: for 12th Graders, 1989–2009, c Being Injured without a Weapon: for 12th Graders, 1989–2009, d Being Injured with a Weapon: for 12th Graders, 1989–2009

Trends of estimated parameters of zero-inflated Poisson distributions by GPA and religious orientation, MTF, 1989 to 2009. a Being Threatened without Injury: for 12th Graders, 1989–2009, b Being Threatened with a Weapon: for 12th Graders, 1989–2009, c Being Injured without a Weapon: for 12th Graders, 1989–2009, d Being Injured with a Weapon: for 12th Graders, 1989–2009

Trends of estimated parameters of zero-inflated Poisson distributions by race and maternal education, MTF, 1989 to 2009. a Being Threatened without Injury: for 12th Graders, 1989–2009, b Being Threatened with a Weapon: for 12th Graders, 1989–2009, c Being Injured without a Weapon: for 12th Graders, 1989–2009, d Being Injured with a Weapon: for 12th Graders, 1989–2009

Different from the upward trends of the estimated intensity of school bullying, the estimated proportions of individuals exposed to bullying behaviors (P) show long-term downward trends across the four bullying behaviors, although a mild increase starting from the year 2005 is exhibited for being threatened with a weapon (Fig. 1b) and being injured without a weapon (Fig. 1c). The largest decrease in the exposure values (P) from 1989 to 2009 occurs for being threatened without injury (Fig. 1a), which declines from 35.0 % in 1989 to 25.8 % in 2009. Such decreases in the exposure to bullying victimization are consistent with declining percentage of violent victimizations at school reported elsewhere (Robers et al. 2012; Molcho et al. 2009).

As will be seen throughout these analyses, the estimates of the two parameters of the ZIP distributions tend to move in opposite directions. For example, when the likelihood (P) of a particular bullying behavior goes up the intensity (λ) or number of bullying experiences per exposed student goes down. Substantively, this corresponds to a widening of the set of 12th graders exposed to the risk of bullying (i.e., an increased P) who are subjected to lower rates of bullying (i.e., five or fewer incidents), thus bringing down the estimated overall intensity of the bullying frequency distribution (i.e., a decreased λ). Conversely, when the set of 12th graders exposed to the risk of bullying narrows (i.e., a decreased P) those who remain at risk of bullying experience higher relative frequencies/intensities of bullying events (i.e., an increased λ). This inverse relationship does not always hold, as there are specific time periods and specific types of serious school bullying for which both ZIP parameters increase or decrease in unison; see, for instance, Fig. 1c for the being injured without a weapon bullying outcomes for the years 2006 to 2009. Overall, however, the inverse temporal movement of the two ZIP parameters is evident for most time periods and bullying outcomes shown in Fig. 1.

The sex disparity in bullying victimization is illustrated in Fig. 2. Across all four types of bullying behaviors, it is clear that boys have higher risks of bullying victimization than girls over the entire period of study. An increase in exposure is observed for boys threatened with a weapon from 1989 to 1994 (Fig. 2b), while the trend of this type of bullying is more flat for girls during the same period. While overall a steady decrease of bullying exposure is shown for being injured with a weapon after the year 2005 (Fig. 1d), the recent decrease in bullying exposure is restricted to boys rather than girls (Fig. 2d). The trends of exposure for being threatened without injury (Fig. 2a) or being injured without a weapon (Fig. 2c) for boys and girls are relatively flat and parallel to each other. In terms of the intensity of bullying victimization, boys also show higher levels of bullying intensities compared to girls for all four types of bullying behavior from 1989 to 2009. For 12th graders injured with a weapon (Fig. 2d), the recent upsurge in the intensity of bullying only appears for boys, whereas the increase in the intensity of bullying victimization is relatively flat for girls.

Students from single- or no-parent families have higher risks of bullying victimization compared to students from two-parent families (see Fig. 3). From 1989 to 2009, students from two-parent families show consistently lower and declining levels of exposure for all four behaviors studied, while estimated levels of exposure of students from single- or no- parent families have fluctuated more. The most salient difference in bullying exposure happens with being injured with a weapon (Fig. 3d) in 2009, where the proportion exposed to bullying for students from single- or no-parent families (10.5 %) is more than twice the corresponding value for students from two-parent families (4.9 %). The intensities for being injured without a weapon and with a weapon fluctuated for the 12th grade students from both family types over the period of study. There was virtually no difference in the intensity of being threatened without injury (Fig. 3a) by family type from 1989 to 1999 and for being threatened with a weapon (Fig. 3b) from 1989 to 1992, after which time the intensities for students from single- or no-parent families increased.

Among the nine covariates examined in this research, only two, sex and family structure, show persistent disparities in both exposure (P) to, and intensity (λ) of, bullying victimization across all four targeted behaviors. The remaining seven covariates show either persistent disparities in bullying exposure for all bullying behaviors (academic performance, religious orientation and religious attendance) or meaningful differences in bullying exposure for certain bullying behaviors (maternal education, paternal education, and race), or have persistent disparities in intensities of bullying victimization for all bullying behaviors (race and residential location). In Fig. 4, only results for bullying exposure are presented because disparities in intensities of bullying victimization are indiscernible over the period of study. As shown in Fig. 4, students with better academic performance (A- and above) have consistently less exposure to bullying victimization from 1989 to 2009. The differential exposure is most evident for being threatened or injured with a weapon (see Figs. 4b and d, respectively). Students that regard religion as important also have less exposure to bullying victimization over most of the study period, although the trends in bullying exposure of students with different religious attitudes tend to converge (for being injured without a weapon, Fig. 4c) or even cross (for being injured with a weapon, Fig. 4d) after the year 2005. The association between religious attendance and bullying exposure largely follows the same pattern (results not shown). Students with rare or no religious attendance have consistently higher levels of exposure to bullying victimization across the study period, although the disparities diminish for being threatened with a weapon or cross over for being injured without a weapon in more recent years.

Whereas no clear patterns in the association between parental education and bullying intensities are evident, students with lower maternal education show higher levels of bullying exposure for being threatened or injured with a weapon (Figs. 5b and d). For the other two targeted behaviors without the use of a weapon (Figs. 5a and c), students with lower maternal education have, however, lower levels of exposure over most of the period studied, although such differences in bullying exposure are relatively small. Likewise, levels and trends of bullying exposure reported by students with differential paternal education are very similar to those reported by students with differential maternal education despite more fluctuations in the association between paternal education and bullying exposure (results not shown). There are also reversed race disparities in bullying exposure. As shown in Figs. 5a and c, African-American students have lower levels of exposure to bullying behaviors without the use of a weapon over most of the period examined. However, this race disparity is dramatically reversed for bullying behaviors involving the use of a weapon, where higher levels of exposure to being injured or threatened with a weapon are reported by African-American students (Figs. 5b and d).

The temporal trend in race disparity in the intensities of bullying victimization is presented in Fig. 6. The difference in the intensities of experiencing bullying for African American and non-African American 12th graders fluctuates greatly for all types of bullying over the period of study. The mid-1990s show a stronger intensity of African American students being injured with a weapon (1.49 in 1996) compared to non-African American students (see Fig. 6d). The intensity for African American students being injured with a weapon increased again, although not so markedly, from 2001 to 2003, and has been increasing since 2005. The highest intensities experienced by African Americans peaked in the mid-2000s for the three other types of bullying. A surprising outcome is that African American students largely show lower intensity in being threatened without injury (see Fig. 6a) until 2003. Since our exposure analyses also shows that African American students have less exposure in the same bullying behavior (see Fig. 5a), these findings may suggest the importance of distinguishing bullying behaviors. With regard to the influence of residency,Footnote 2 students living in rural areas have consistently higher and more fluctuating levels of bullying intensity for all four types of bullying victimization from 1989 to 2009. Compared to students living in urban areas, 12th graders in rural areas experienced a recent upsurge in bullying intensity of all four targeted behaviors, whereas a recent upsurge in bullying intensity only exists for urban 12th graders exposed to being injured with a weapon.

Trends of estimated parameters of zero-inflated Poisson distributions by race and residential location, MTF, 1989 to 2009. a Being Threatened without Injury: for 12th Graders, 1989-2009, b Being Threatened with a Weapon: for 12th Graders, 1989–2009, c Being Injured without a Weapon: for 12th Graders, 1989–2009, d Being Injured with a Weapon: for 12th Graders, 1989–2009

Finally, the question can be raised as to whether the annual changes and trends in the estimated exposure and intensity parameters of the zero-inflated Poisson distributions of the annual frequency distributions of the four types of bullying victimization reported above are statistically significant and not merely random fluctuations. Because the current research focuses on the annual changes and trends of bullying victimization over time instead of the accuracy with which the ZIP parameters are estimated from the MTF sample in a specific year, time-series standard deviations were calculated. For this, a moving-average time series model specification (Kendall and Stuart 1976: 380–418) was adopted to define the trend in the expected values of the estimated exposure and intensity parameters for each year from 1989 to 2009. That is, the expected value of each of the parameters for each year t is assumed to vary over time but to tend towards an expected or mean value that is defined “locally.” Specifically, the expected value of, say, the estimated exposure parameter P for a specific bullying victimization behavior for year t is specified to be the three-year average of the estimated values of P for years t-1, t, and t + 1.Footnote 3

The standard deviations of the estimated values of the ZIP parameters then can be calculated as deviations of the estimated values of each parameter for each year from the corresponding expected values, squaring the deviations, summing across the years, and taking square roots. As could be anticipated, the resulting estimated time-series standard deviations shown in Table 3 tend to be larger for those estimated ZIP parameters that visually fluctuate more widely in the graphs reviewed above. Generally, however, year-to-year changes in either bullying exposure or intensity are largely several times of corresponding time-series standard errors. For example, the estimated ZIP bullying exposure parameter P for African-American students declined 1.7 % from 1989 (17.2 %) to 1990 (15.5 %), which is around five times of the corresponding time-series standard deviation (0.31 %). In sum, the estimated time series standard deviations of the estimated ZIP parameters of the annual frequency distributions of the bullying behaviors reported in Table 3 generally indicate that both the year-to-year changes and the long-term trends from 1989 to 2009 are statistically significant. Accordingly, these changes and trends can be meaningfully interpreted as indicative of substantively significant changes in the annual frequency distributions of the underlying bullying behaviors, as has been done above in our descriptions of the graphs shown in the figures.

6 Discussion and Conclusions

The foregoing analyses yield several findings regarding trends and patterns in school bullying among 12th graders in the US across the two decades from 1989 to 2009. First, with regard to the intensity (λ) of bullying victimization, there is substantial empirical evidence of an upturn for all forms of school bullying for 12th graders that began in 2002–2003 and extended through the end of the decade. This echoes a smaller upward wave in school bullying that occurred in the late-1980s and early-1990s. In other words, there indeed is empirical evidence of an increase in school bullying in the mid-to-late-2000s so that the increased media reporting of teenage bullying incidents is not just a media event, but rather has an empirical evidentiary base. However, this recent wave of bullying victimization is not unique in US history, as the empirical record shows the prior wave of bullying victimization. Second, the long-term trend in the percent of students at risk (P) of school bullying over the two most recent decades is down, with declines ranging from four to 11 percentage points depending on the category of bullying behavior studied. Thus, the risk of experiencing serious bullying victimization for 12th graders was lower in recent years than in the early 1990s. Third, the analyses reveal differences in bullying experiences are a function of a series of socio-demographic and behavioral factors. Across all four targeted behaviors, boys and students from no- or single-parent families show consistently higher levels of both bullying exposure and bullying intensity over most of the period since 1989. And, while students with lower school performance, weaker religious attachment, and less religious attendance show consistently higher risks of being bullied, African American students and students living in cities largely experience more intensified school bullying. Fourth, this study points to heterogeneity among types of bullying victimizations with respect to their associations with socioeconomic and race covariates. For bullying behaviors involving the use of a weapon, African-American background and lower parental education are associated with higher levels of bullying exposure. However, such disparities in the exposure to bullying behaviors are reversed for bullying behaviors without the use of a weapon.

In addition to corroborating the well-documented sex disparity in school bullying, our analyses point to the significance of family structure in influencing school bullying. One possible explanation is that, due to weak or absent parent–child relationships, students from no- or single-parent families may be deprived of opportunities for building their social skills and capacity via parent–child interaction, which make them more vulnerable to bullying victimization (Arora 1987; Bowers et al. 1994). The association between religion and the intensity of school bullying, which was rarely reported in previous research, may suggest the role of social isolation in shaping bullying behaviors given the fact that religious involvement has a strong influence on social support and social networks (Ellison and George 1994; Schuster 1999). When the most frequent reason given by middle- and high-school students for bullying victimization is that victims “don’t fit in” (Hoover et al. 1992: 11), students who are more socially isolated and rejected by peers tend to be targets of school bullying (Nansel et al. 2001). By replicating findings from existing research, our analyses also corroborate existing findings that school bullying is not a city problem and students with lower school performance are at higher risks of school bullying. Finally, differential socioeconomic status disparities in different bullying behaviors deserve attention. For example, African-American 12th graders were found to be less likely to have the exposure to and intensity of being threatened without injury, the least serious bullying behaviors examined in this research, but are more likely to experience the more harsh forms of bullying, those that involve weapons and being injured. Such reversed socioeconomic status disparities also exist in the association between parental education and bullying exposure. Since educational attainment and race are intertwined indicators of social stratification, these findings suggest that students from lower-socioeconomic status families are more likely to be victims of harsher forms of bullying. Nonetheless, a full understanding of these findings requires additional research. For instance, certain bullying behaviors are associated with instrumental needs, such as gaining property (Dodge 1991), may be associated with more extreme forms of bullying.

It should be noted that several limitations of this research lend caution to interpretation of the findings. First, the bullying measures used in this study reflect self-reports of experiencing serious bullying victimization but fails to identify the types of persons exhibiting the bullying behaviors. Different from the dichotomized classification of bullying-related students as bullies or victims, researchers have suggested a third category of students, bully/victims, who both bully others and are victimized at other times. (Kumpulainen et al. 1998; Sutton and Smith 1999). Although behavioral characteristics of bully/victims are distinct (Forero et al. 1999), this particular group of bullying victims cannot be examined with available data in the MTF. Second, the empirical data we have analyzed are drawn from 12th graders, which make our estimates of bullying victimization at school conservative. Bullying victimization generally decreases in the higher grades because victims of school bullying can gradually develop strategies for coping and escaping school bullying as they grow older (Olweus 1994). Third, the cross-sectional data employed in this study precludes any statement about causality. Therefore, the associations between the covariates investigated and school bullying should not be causally interpreted. It is possible that reverse causal relations exist. For instance, it remains unclear whether worse school performance causes bullying victimization or whether being bullied leads to worse school performance, possibly mediated by skipping classes and less participation in school-related activities (Batsche and Knoff 1994). Therefore, the findings presented here are insufficient to guide intervention programs and policy development.

Despite these limitations, this study extends the body of literature on school bullying in several ways. By distinguishing bullying exposure from bullying intensity, this research devises an innovative method to extract information from a national representative dataset and reveals the long-term trends of school bullying in the US. The repetitive trends of bullying intensity and downward trends of bullying exposure are, to our knowledge, first reported here. Finally, this research demonstrates the persistent disadvantage of several socio-demographic and behavioral groups in bullying victimization. The association between certain covariates (family structure, religious attendance and religious orientation) and school bullying also have been rarely reported by previous studies.

While it is imperative to identify groups of students who are at greater risk of school bullying, the persistent disadvantage shown in this study should by no means be interpreted as suggesting that the bullying problems among students less at risk of school bullying (such as girls, non-African Americans and students from intact families) deserve little attention. To the contrary, such problems should also be acknowledged and addressed by parents, teachers, scholars and policy makers.

Notes

We also examined the effects of maternal employment (no employment or employed some of the time vs. employed all of the time or most of the time) on bullying victimization. However, 12th graders with differential maternal employment tend to have similar trends and levels of school bullying (results available on request).

Because the rural–urban disparity in bullying exposure fluctuates widely over the period of study, only estimated bullying intensities are reported in this study.

For the first and last years of the time series of estimated parameters, two-point moving averages are applied.

References

Arora, T. C. M. J. (1987). Defining bullying for a secondary school. Education and Child Psychology, 4(3), 110–120.

Batsche, G. M., & Knoff, H. M. (1994). Bullies and their victims: understanding a pervasive problem in the schools. School Psychology Review, 23(2), 165–175.

Benbenishty, R., & Astor, R. (2005). School violence in context: culture, neighborhood, family, school, and gender. New York: Oxford University Press.

Berger, K. S. (2007). Update on bullying at school: science forgotten? Developmental Review, 27(1), 90–126.

Bosworth, K., Espelage, D. L., & Simon, T. R. (1999). Factors associated with bullying behavior in middle school students. The journal of early adolescence, 19(3), 341–362.

Bowers, L., Smith, P. K., & Binney, V. (1994). Perceived family relationships of bullies, victims and bully/victims in middle childhood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 11(2), 215–232.

Carney, A. G., & Merrell, K. W. (2001). Bullying in schools: perspectives on understanding and preventing an international problem. School Psychology International, 22(3), 364–382.

Dishion, T. J. (1990). The family ecology of boys’ peer relations in middle childhood. Child Development, 61(3), 874–892.

Dodge, K. A. (Ed.). (1991). The structure and function of reactive and proactive aggression (the development and treatment of childhood aggression). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Duncan, A. (2010). The Myths About Bullying: Secretary Arne Duncan’s Remarks at the Bullying Prevention Summit Accessed April 21 2012.

Ekblad, S., & Olweus, D. (1986). Applicability of Olweu’s aggression inventory in a sample of Chinese primary school children. Aggressive Behavior, 12(5), 315–325.

Ellison, C. G., & George, L. K. (1994). Religious involvement, social ties, and social support in a southeastern community. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 33(1), 46–61.

Espelage, D. L., & Swearer, S. M. (2003). Research on school bullying and victimization: what have we learned and where do we go from here? School Psychology Review, 32(3), 365–383.

Forero, R., McLellan, L., Rissel, C., & Bauman, A. (1999). Bullying behaviour and psychosocial health among school students in New South Wales, Australia: cross sectional survey. British Medical Journal, 319, 344–348.

Fox, J. (2008). Applied regression analysis and generalized linear models. Los Angeles: Sage Publications, Inc.

Gelman, A., & Hill, J. (2007). Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Graham, S., & Juvonen, J. (2002). Ethnicity, peer harassment, and adjustment in middle school. The journal of early adolescence, 22(2), 173–199.

Greenbaum, S., Turner, B., & Stephens, R. D. (1989). Set straight on bullies. Los Angeles: Pepperdine University Press.

Hoover, J. H., Oliver, R., & Hazler, R. J. (1992). Bullying: Perceptions of adolescent victims in the midwestern USA. School Psychology International, 13(1), 5–16.

Hu, W. (2011). Bullying law puts New Jersey schools on spot. The New York Times, p. A1.

Johnston, L. D., Bachman, J. G., & O’Malley, P. M. (1989). Monitoring the future: A continuing study of the lifestyles and values of youth, 1989. In U. o. Michigan (Ed.). Ann Arbor.

Kumpulainen, K., Räsänen, E., Henttonen, I., Almqvist, F., Kresanov, K., Linna, S.-L., et al. (1998). Bullying and psychiatric symptoms among elementary school-age children. Child Abuse & Neglect, 22(7), 705–717.

Lambert, D. (1992). Zero-inflated poisson regression, with an application to defects in manufacturing. Technometrics, 34(1), 1–14.

Lim, C., & Putnam, R. D. (2010). Religion, social networks, and life satisfaction. American Sociological Review, 75(6), 914–933.

Long, J. S., & Freese, J. (2006). Regression models for categorical dependent variables using stata. College Station: Stata Press.

Maccoby, E. E., & Jacklin, C. N. (1980). Sex differences in aggression: a rejoinder and reprise. Child Development, 51(4), 964–980.

Massey, D. S., & Denton, N. A. (1988). The dimensions of residential segregation. Social Forces, 67(2), 281–315.

Molcho, M., Craig, W., Due, P., Pickett, W., Harel-Fisch, Y., Overpeck, M., et al. (2009). Cross-national time trends in bullying behaviour 1994–2006: findings from Europe and North America. International Journal of Public Health, 54(2), 225–234.

Nansel, T. R., Overpeck, M., Pilla, R. S., Ruan, W. J., Simons-Morton, B., & Scheidt, P. (2001). Bullying behaviors among US youth: prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 285(16), 2094–2100.

Nansel, T. R., Overpeck, M. D., Haynie, D. L., Ruan, W. J., & Scheidt, P. C. (2003). Relationships between bullying and violence among US youth. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 157(4), 348.

National Education Goals Panel. (1993). The national education goals report: volume One. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Olweus, D. (1980). Familial and temperamental determinants of aggressive behavior in adolescent boys: a causal analysis. Developmental Psychology, 16(6), 644–660.

Olweus, D. (1991). Bully/victim problems among schoolchildren: basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program (The development and treatment of childhood aggression). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Olweus, D. (1994). Bullying at school: basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 35(7), 1171–1190.

Perry, D. G., Kusel, S. J., & Perry, L. C. (1988). Victims of peer aggression. Developmental Psychology, 24(6), 807–814.

Rigby, K. (2002). New perspectives on bullying. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Robers, S., Zhang, J., Truman, J., & Snyder, T. D. (2012). Indicators of school crime and safety: 2011. In U. S. D. o. E. National Center for Education Statistics, and Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice (Ed.). Washington, DC.

Roland, E. (Ed.). (1989). A system oriented strategy against bullying (Bullying: An international perspective). London: David Fulton Publishers.

Salsman, J. M., Brown, T. L., Brechting, E. H., & Carlson, C. R. (2005). The link between religion and spirituality and psychological adjustment: the mediating role of optimism and social support. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(4), 522–535.

Schuster, B. (1996). Rejection, exclusion, and harassment at work and in schools. European Psychologist, 1(4), 293–317.

Schuster, B. (1999). Outsiders at school: the prevalence of bullying and its relation with social status. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 2(2), 175–190.

Schwartz, D., Farver, J. M., Chang, L., & Lee-Shin, Y. (2002). Victimization in South Korean children’s peer groups. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30(2), 113–125.

Smith, P. K., & Myron-Wilson, R. (1998). Parenting and school bullying. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 3(3), 405–417.

Smith, P. K., & Sharp, S. (1994). School bullying: Insights and perspectives. London: Routledge.

Sourander, A., Helstelä, L., Helenius, H., & Piha, J. (2000). Persistence of bullying from childhood to adolescence–a longitudinal 8-year follow-up study* 1. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24(7), 873–881.

Srabstein, J. (2008). Deaths linked to bullying and hazing. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 20(2), 235–239.

Sutton, J., & Smith, P. K. (1999). Bullying as a group process: an adaptation of the participant role approach. Aggressive Behavior, 25(2), 97–111.

Whitney, I., & Smith, P. K. (1993). A survey of the nature and extent of bullying in junior/middle and secondary schools. Educational Research, 35(1), 3–25.

Wilson, W. J. (1987). The truly disadvantaged: The inner city, the underclass, and public policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Woods, S., & Wolke, D. (2004). Direct and relational bullying among primary school children and academic achievement. Journal of School Psychology, 42(2), 135–155.

Zeileis, A., Kleiber, C., & Jackman, S. (2008). Regression models for count data in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 27(8), 1–25.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This research was supported by a research grant from the Foundation for Child Development.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, Q., Land, K.C. & Lamb, V.L. Bullying Victimization, Socioeconomic Status and Behavioral Characteristics of 12th Graders in the United States, 1989 to 2009: Repetitive Trends and Persistent Risk Differentials. Child Ind Res 6, 1–21 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-012-9152-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-012-9152-8