Abstract

This article examines alternative and supplementary ways in which theorists and researchers have sought to account for bullying behavior among students in schools. Contemporary explanations acknowledge the variety, complexity, and interactivity of both person and environmental factors in determining acts of bullying in schools. Two explanatory models or frameworks are described: (i) an adaptation of the theory of planned behavior proposed by Ajzen (Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50:179–211, 1991); and (ii) the comprehensive model of bullying (CMB) by Rigby (Multiperspectivity in school bullying, page 64. Routlege, 2021b). The strengths and limitations of these models are discussed, together with applications in addressing school bullying.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The rise of concern since the early 1990s over bullying in schools has led to a proliferation of theoretical explanations for why it is so prevalent among schoolchildren. Estimates derived from 71 countries reported by UNESCO (2019) suggest that around 32% of schoolchildren between the ages of 9 and 15 years were bullied for one or more days during the previous month. Analyses of trend data by UNESCO have shown that despite increasing attention to the problem, over half (55%) of these countries have reported no significant reductions. Although some carefully evaluated interventions to reduce bullying in schools have been modestly successful (Ttofi & Farrington, 2011), a large majority have had little or no effect. At the same time, numerous studies have shown that bullying behavior has the effect of seriously reducing the wellbeing and mental health and learning of victimized students (Armitage, 2021). In the light of these findings, more effective means of intervening to reduce bullying are needed, and these need to be grounded in an understanding of why bullying takes place in schools. This article seeks to examine a range of theoretical explanations for bullying behavior and describes two models that exhibit both strengths and limitations in describing why bullying occurs in schools and how it may be countered.

Explanations must begin an acceptable definition of bullying. It is conceived as a subset of aggression. Although some views on what precisely constitutes bullying behavior remain controversial, the formulation of the definition proposed by Olweus (1993, p.9) has been broadly accepted by most researchers: that is, “a student is being bullied or victimized when he or she is exposed repeatedly and over time to negative actions on the part of one or more other students.” Crucial elements generally include (i) bullying is intentional and deliberate; (ii) it occurs in a situation in which there is an imbalance of power; and (iii) it is repeated over time. What may constitute “negative actions” has expanded more recently to include not only direct actions such as striking people and face-to-face verbal abuse, but also indirect negative actions such as exclusion, rumor spreading, and cyber bullying. In general terms, bullying has been viewed as a systematic abuse of power (Smith & Sharp, 1994) and by Tattum and Tattum (1992, p.147) as “a conscious, willful desire to hurt another person and put him/her under stress.” This latter view is inadequate as a definition of bullying, which is recognized as a behavior. However, it draws attention to the motivational core of bullying, which may be seen as a state of mind, specifically a “desire.” Whether bullying can best be understood as a consequence of individual volition, as distinct from broader considerations such as group dynamics and the caring-ness or otherwise of the social milieu, has been questioned in a recent set of recommendations by a UNESCO committee on school violence (Cornu et al., 2022).

This article provides a brief survey of theoretical perspectives that have been thought to be relevant to understanding and explaining bullying in schools, together with supportive empirical findings. Two models purporting to explain bullying are described, linking, where possible, with theoretical formulations and reported findings. The models are then critically discussed as to their adequacy and potential value in assisting schools in addressing the problem of bullying.

Theoretical Explanations

Theoretical explanations of bullying may be categorized under three general headings: (1) the nature of the beast, an idiom that conveys the inherent or essential quality or character of something, which cannot be changed and must be accepted (see Anderson, 2022); (2) the nature of the environment, that is, the aggregate of external agents or conditions—physical, biological, social, and cultural—that influence the functions of an organism (APA, 2022); and (3) interaction between (1) and (2). Although different emphases may be placed on the “nature of the beast” and/or the nature of the environment in explaining bullying in schools, it is generally understood that a full explanation of bullying requires an examination of how each contributes and how the two interact with one another. According to a heuristic formula proposed by Lewin (1936), B = f (P, E), where B is the behavior (in this case “bullying”) and P stands for person—that is, the “beast” in question—and E is the environment.

Evolutionary psychology has produced a basic explanation of bullying that emphasizes what is “given” in the nature of living beings. Bullying is seen as an evolved adaptive strategy, practiced by both non-humans and humans, that offers benefits to its practitioners through the achievement of somatic, sexual, and dominance goals (Volk et al., 2012). Evolutionary theories of bullying acknowledge the significant role that the environment may play in the development of bullying behavior. However, as pointed out by Volk et al., despite substantial variations in environmental conditions, bullying among students is prevalent in all countries.

Related to the evolutionary view of bullying is the so-called dominance theory (Evans & Smokowski, 2016), according to which individuals and groups are motivated to bully others in order to gain and secure social capital, that is, to the benefits gained from social relationships (Putnam, 2000). Dominance per se may be for some individuals a means to an end, rather than an end in itself.

Consistent with the claims of evolutionary psychologists, there is evidence that the tendency of children to bully others is influenced by genetic factors. For instance, it has been reported that identical twins are significantly more likely to be similar in their tendency to bully others than are fraternal twins, even when the identical twins are reared apart (Ball et al., 2008). More recently, genetic material derived from analyses of samples of blood and saliva has been used to predict bullying behavior of children, as rated by fellow students (Musci et al., 2018). This is not to deny the influence of environmental factors but rather to support the view that genetics play an influential role in explaining bullying behavior.

Some explanations of bullying behavior emphasize the role of personality conceived as a set of relatively enduring psychological characteristics that affect the way people behave. For instance, Farrell and Volk (2017) see bullying as the product of an anti-social personality described by them as a predatory, exploitive personality trait. Research findings based on personality assessments indicate that children who bully tend to be relatively extraverted, psychotic, sadistic, narcissistic, Machiavellian, disagreeable, and deficient in emotional empathy (Vangeel et al., 2017). These qualities are, to some degree, genetically determined (Veldkamp et al., 2019). A further claim is that bullying behavior can be explained by psychoanalytical theory, according to which bullying can be seen as the outcome of a disposition to protect one’s ego through the use of projection and/or scapegoating (Dixon & Smith, 2011; Wampold, 2015).

In explaining aggression, a central role has sometimes been accorded to the consequences of frustration and/or being placed under considerable strain through negative life events with which a person is unable to cope. The classic definition of frustration in psychology is any event or stimulus that prevents an individual from attaining a goal and its accompanying reinforcement quality (Dollard et al., 1939). On the basis of empirical studies, it has been reported that experiencing frustration, even if unintended, commonly leads to a person acting aggressively (Berkowitz, 1989). This may include bullying behavior. For instance, levels of school bullying have been reported as relatively high in schools in England where community resentment and associated frustration have been aroused by increases in foreign migration (Denti, 2021). For some students and families, such perceived “intrusion” may constitute a strain leading to anti-social acts such as bullying (Agnew, 1992).

At the same time, not every instance of frustration or negative life events leads to acts of interpersonal aggression. Hence, one aspect or dimension of personality relevant to bullying is tolerance of frustration. As predicted, Potard et al. (2021) have confirmed that adolescent schoolchildren in France who were identified as bullies were more likely than those not involved bullying to report a relatively low level of tolerance of frustration on a Frustration Discomfort Scale. This result was significant on two subscales, one relating to entitlement, “I can’t stand it when people go against my wishes,” and one to achievement, “I can’t bear the frustration of not achieving my goals.”

Persons may be described according to cognitive capacities or modes of thinking that are related to bullying. Explanations of bullying may be derived from cognitive theory as developed by Bandura (1999). It has been reported that children who bully tend to be morally disengaged (Hymel & Bonnanno, 2014). They commonly invent reasons why a victim deserves to be hurt and are untroubled by any scruples (Thornberg & Jungert, 2014). It has been further claimed that having a greater cognitive capacity for discerning what others may be thinking, as in theory of mind, may advantage some prospective bullies who choose to exploit this capacity (Smith, 2017).

The person (P) in the Lewin formulation may also include age and gender. Both these factors have been found to be related to bullying behavior. Increases in its prevalence in schools have been reported as occurring in early adolescence. Boys are more commonly reported as perpetrators, at least as far as physical bullying is concerned; however, this difference may not extend to other forms of bullying, such as verbal and cyber bullying (Menesini & Salmivalli, 2017) and can depend on the cultural background (Rigby et al., 2019).

The Environment (E)

The most general theory to account for behavior including bullying is reinforcement theory, as propounded by Skinner (1953). This theory dismisses the need to postulate any internal states, such as “desire” to explain bullying behavior. It is claimed that all bullying can best be understood as a consequence of certain actions, defined as bullying, being taken and positively reinforced. Positive behavior support programs in schools to counter bullying are based on the assumption that bullying will cease if it is not reinforced (Ross & Horner, 2009). In more recent years, learning theorists have sought to explain bullying by expanding the “purer” Skinnerian version of how learning occurs to include more cognitive factors and the importance of modeling in the acquisition of bullying behaviors (Bandura, 1977).

Other explanations specify features of the environment that give rise to bullying. These may include physical features such as the ambient temperature in one’s locality (Wei et al., 2017) and the built environment in which one spends time (Fram & Dickman, 2012). More commonly, attention is paid to the social environment, past and present. Following the seminal work of Bronfenbrenner (2009), a variety of social systems and influences have been identified as contributing to bullying behavior (See Espelage, 2014; Swearer & Hymel, 2015; Hornby, 2015). These include interacting microsystems in the immediate environment, such as the home, the local neighborhood, and the school. Other more expansive systems involve society and culture, within which government policies, the Law, and the media may play a part (Rigby, 2021b). Each of these ecological systems is conceived as interacting with and influencing each other in all aspects of the children’s lives, including their interpersonal relations at school, and may, in some circumstances, result in bullying.

Research findings have supported some of the claims that aspects of the social ecology may influence the occurrence of bullying in schools. The home environment of children who experience cold, authoritarian parenting has been reported as being more likely than others to bully their peers at school (Connell et al., 2016; Rigby, 2013). Levels of reported bullying in school have been found to be much higher in some neighborhoods and communities than others; for example, they have been reported to be significantly higher in countries with greater economic inequality (Elgar et al., 2009). The ethos of the school attended by a child, as indicated by prevailing attitudes, values, and behaviors of students and teachers, is reportedly related to how children interact with their peers, with bullying perpetration being less prevalent in schools in which children feel supported by school staff (Modin et al., 2017; Thornberg et al., 2018). Social norms endorsed by peer or friendship groups, especially in relation to negative treatment of outsiders and those against whom there is bias or prejudice, are seen as contributing to bullying (Perkins et al., 2011).

The complexity of explaining bullying within an ecological framework becomes evident when the nature of interactions between the factors is considered. For example, the influence of an oppressive home environment may have more adverse consequences for a child when combined with negative school ethos, or have a less negative effect if combined with positive relations with teachers.

Interactions Between P and E

Reverting to the Lewin formulation, as adapted, B (bullying) = f (P, E), one may ask how in practice this may help in explaining bullying. It requires us to consider how effects traceably to the environment are modified in accordance with the nature of individual persons. One might expect some ecological factors to influence bullying behavior more so or less so, according to the personal qualities of the child. As an example, a child with a low tolerance of frustration may become aggressive and engage in bullying in one school, but not in another school where he or she is helped by a teacher to control negative emotions. The relationship between a person and the environment can be viewed as reciprocal. A person is not only acted on by the environment but may also act to modify the environment, which in turn may produce changes in the person. For instance, learning not to over-react to provocation may lead to a change in how a child is treated by others at school, that is, produce a change in the social environment and, as a consequence, how he or she subsequently treats others.

A number of heuristic models have been constructed to identify factors, relationships, and inter-relationships that are thought to be relevant to understanding and explaining bullying in schools. They may differ in two ways: first according to the selection of variables considered relevant and, second, whether they indicate a “process” according to which selected independent variables bring about bullying behavior.

A wide range of relevant variables have been suggested by Astor and Benbenishty (2018). These are differentiated according to whether they are (i) internal factors, that is, ones that operate within a school, such as school climate, school leadership, availability of resources, and disciplinary procedures, and (ii) external factors, such as home background, neighborhood, and the mass media. Internal and external factors are seen as interacting in ways that may change over time. Person factors, apart from age and gender, are not considered; genetic influences or personality or attitude variables are not seen as playing any part. Acknowledging that evidence for the associations between measures of the factors is correlational, the authors do not claim directional, causal links between the variables. They point out, for instance, that a reduction in bullying in a school may result in an improvement in the school climate, which may further reduce bullying prevalence. Whilst their contribution notes a wide range of ecological factors that may influence bullying behavior, they do not attempt to show how such factors may, in combination, determine bullying behavior. The two models to be examined in this article describe or imply a “process” according to which environmental and person-related variables in combination give rise to bullying behavior.

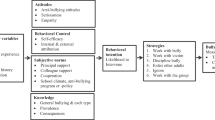

The first model is derived from the theory of reasoned action (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980), further elaborated by Ajzen (1991) in the theory of planned behavior. In an adaptation of this model (Rigby, 1997), three factors were identified as interacting and contributing to the intention to bully someone, (i) personal attitudes towards bullying behavior, seen as a consequence of a history of reinforcement following acts of bullying, (ii) perceived or subjective norms regarding bullying, and (iii) perceived behavioral control, that is, belief in one’s capacity to carry out the action of bullying. Factors (i) and (iii) are regarded as related to person. Normative influences, filtered through individual perceptions, relate to the environment. Collectively, these factors were thought to predict intention to act. Ajzen claimed that the intention to act is closely related to actually doing so. Thus, if a person has a positive attitude towards bullying behavior, believes that significant others, for example, a friendship group, actually support bullying behavior, and holds the belief that he or she is able to bully someone, then, according to the model, bullying is more likely to result. Unlike the model proposed by Astor and Benbenishty, hypothesized relationships predicting bullying behavior are testable (see Fig. 1).

Application of the model of planned behavior to bullying, based on Ajzen (1991)

The planned behavior model has some theoretical and empirical support. It draws upon principles of reinforcement theory as applied in bullying interventions (Ross & Horner, 2009) and also upon social cognitive theory in highlighting the influence of perceived social norms among students (Burns et al., 2008; Salmivalli, 2010). The model includes the factor of perceived capability to perform an act of bullying, thereby recognizing that it can occur in circumstances in which there is an imbalance of power favoring the bully (Olweus, 1993). This model has used in several studies of adolescent schoolchildren to predict intention to bully (Rigby, 1997) and, more specifically, to engage in cyber bullying (Pabian & Vandebosch, 2014; Auemaneekul et al., 2020; Siriporn, 2021). In each study, all three factors, independently and collectively, made significant contributions.

A second model is more comprehensive in its inclusion of factors that may influence bullying behavior and also includes a description of how what may follow once the intention to bully has been made. The comprehensive model of bullying (CMB) as described by Rigby (2021b) is distinctive in being based largely on the assumption made by Tattum and Tattum that bullying behavior is driven primarily by a desire on the part of a perpetrator to hurt or place someone under stress. Desire is seen here as a disposition or state of mind to act to bring about a specific outcome (Anscombe, 2000; Rigby, 2012a, b, 2021b). It assumes that this hypothesized desire is determined by genetic or personality factors, together with a range of ecological factors. The stronger the influence in increasing the desire to hurt or place someone under stress, the more likely it is that a child will engage in aggressive and possibly bullying behavior. How the hypothesized desire may be generated is suggested in Fig. 2, together with possible sequelae.

As in the formulation of Astor and Benbenishty, a number of relevant environmental factors are identified. These include an authoritarian and abusive home background (Georgiou et al., 2013), a troublesome neighborhood (Bowes et al., 2009), and a negative school ethos (Modin et al., 2017) as indicated by negative relations between students and staff members. Negative and non-accepting attitudes towards other students may also contribute to bullying behavior. A qualitative study of how students in primary and secondary schools in Australia felt about “children at this school” indicated that negative judgements were expressed by 24% of the students, as in being “stupid,” “mean,” “bitchy,” “stuck up,” “uncool,” and “idiots.” Students making such judgements were also significantly more likely than others to report engaging in bullying at school (Rigby & Bortolozzo, 2013).

A set of person factors are also identified, including extraversion, low empathy, disagreeableness, and sadism. The environmental and person factors are seen as contributing in some way, directly or through interaction with each other, to produce a frame of mind characterized as having, in varying degrees, a desire to act hurt or pressure another person, and which under some conditions and circumstances could result in bullying behavior.

Whether children actually engage in aggressive behavior is seen to depend, in part, on whether the desire is sufficiently intense and sustained. It may dissipate over time without any aggression being expressed. Whether any aggression involves bullying (as distinct from conflict between individuals or groups of equal or similar power) may depend in part on the moral engagement or otherwise of the potential perpetrator. Morally disengaged students are seen as more likely to engage in bullying. Such disengagement is likely to be influenced by group membership and the social norms they share, as well as by personal prejudice (Iannello et al., 2021).

This model also draws attention to possible sequelae. These include (i) decisions made as to the person or persons to be targeted; (ii) the method(s) to be employed in carrying out the bullying, e.g., physical, verbal, and/or cyber; (iii) reactions of the targeted person(s) when the bullying is attempted, e.g., resisting and calling on help; (iv) opposing (restraining) or supporting (facilitating) bystander responses; and (v) the perceived presence and effectiveness of teacher surveillance and/or intervention. Given the perceived “successes, and especially the satisfaction it gives to the perpetrator, one might expect in some cases a cycle would be set up, with others joining in, so that the bullying becomes more difficult to stop.

Discussion

Finding better, more comprehensive explanations for the occurrence of bullying in schools is an important step towards developing anti-bully policies and effective method of prevention and intervention. Many suggestions have been made as to the origins of this prevalent and harmful form of behavior. Various explanations have been proposed drawing on evolutionary psychology, behavioral genetics, reinforcement theory, frustration-aggression theory, strain theory, personality theory, social ecology, and cognitive theory. The models described above draw upon some of the reported findings and theoretical explanation relating to bullying behavior and are consistent with the view that bullying is an outcome of both person and environmental factors.

The model based on the theory of planned behavior recognizes that environmental and personal factors may interact in determining bullying, for instance, perceived social norms and enduring attitudes to bullying (considered a person attribute) seen as derived from a history of reinforcement. It challenges schools to consider how negative social group norms can be countered and the part that can be played through reinforcing positive, pro-social behavior. It also recognizes that bullying necessarily involves a perceived imbalance of power, which may in some cases be reduced, arguably by teaching targeted children to be more assertive, as appropriate. However, it may be criticized in being too narrowly conceived and as not including other factors that need to be taken into account in addressing bullying, such as a genetic predisposition, home background, and school ethos. Finally, it does not recognize the central role of motivation and how a state of mind prone to bully others can be managed.

The CMB provides a more comprehensive explanation of bullying behavior. It draws attention to the contribution of a range of person and environmental factors that have been identified as potentially influencing bullying behavior. It differs from the other models in postulating a state of mind, a desire to hurt or place another under stress, that may, under some conditions, motivate and give rise to bullying behavior. Inspection of the model may enable schools to identify steps that can be taken to prevent bullying or respond effectively to actual cases.

-

1.

First, in focusing on the state of mind in students, namely a desire to hurt or place another under stress as leading to bullying behavior, educators are challenged to examine what they can do to reduce unnecessary sources of frustration or strain in the school for example, by promoting interpersonal empathy (Jolliffe & Farrington, 2006); developing a supportive and caring school environment (Smit & Scherman, 2016); encouraging cooperative learning (Van Ryzin & Roseth, 2019); and working constructively with parents (Healy & Sanders, 2014).

-

2.

It draws attention to students in a chronic or recurrent states of hostility and how they might be helped to regulate their emotions, for example, by teaching techniques of mindfulness (Foody & Samara, 2018) and/or conducting motivational interviewing with students who bully and are seeking help to change their behavior (Cross et al., 2018).

-

3.

In considering the decision-making process whereby a student takes action to bully someone, attention is directed towards the means by which moral disengagement can be discouraged among students through counselling (Campaert et al., 2017).

-

4.

As well as seeking to develop a school ethos that may prevent bullying, the model may encourage schools to develop more effective and appropriate intervention methods, recognizing that a failure to stop cases of bullying from continuing can set up a cycle of bullying that may become more difficult to deal with, as more students may join in the bullying (Rigby, 2012a, b, 2021a).

-

5.

It identifies the importance of bystander behavior, given the strong influence of positive bystander action in stopping cases from continuing (Hawkins et al., 2001; Salmivalli, 2014). Teachers can encourage positive bystander action to assist victims through classroom discussions (Rigby & Johnson, 2006a, 2006b). There is, however, a danger that by their actions bystanders can draw attention to the status of victims and put them more at risk of being bullied (Healy, 2020)–and thereby perpetuate the problem.

Limitations and Criticism

The question remains as to why given experiences, such as perceived social norms supporting bullying and abusive, authoritarian parenting, should result in the desire to hurt and in some cases bullying behavior. Possible explanations for following social norms have included the desire to belong to an admired group who approve of the bullying, the acquisition of a positive self-image, and a fear of rejection and isolation if one adopts a contrary attitude (Gross & Vostroknutov, 2022). Why abusive parenting and negative school ethos may lead to children bullying others may also be seen as a consequence of frustration, especially among students with low tolerance for frustration, as suggested by the frustration-aggression hypothesis.

However, arguably, not all bullying may involve an aggressive intent. The motivation may, for instance, be a desire to increase or maintain one’s status in a group and/or to be admired by some peers (Veenstra et al., 2010). In such cases, the aim is not to hurt, though it may well do so. Parents and others may at times encourage and reinforce such behavior, mindful that their children’s “success” (defined by “social status”) may be achieved by dominating others in ways that may be viewed as non-malign. It may therefore be that the model is limited in its application to bullying behavior that involves an intention of the bully to harm another person. It would be of interest to discover how often a desire to hurt is present in cases of bullying as distinct from bullying that does not include such an element.

Conclusion

According to the famous maxim of Kurt Lewin (1951), there is nothing more practical than a good theory. It is with this expectation that one may follow the trail of his formula, as adapted: B (bullying) = f (P, E). How successful this journey can be remains to be seen. The models presented here were consistent with empirical findings in relating bullying behavior to ecological and person variables. Furthermore, the models discussed can be used to draw attention to points at which appropriate interventions may be undertaken by schools to prevent bullying from occurring or from continuing and provide justifications for various actions in addressing the problem.

References

Agnew, R. (1992). Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology, 30(1), 47–87.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding and predicting social behavior. Prentice Hall.

Anderson, D. J. (2022). The nature of the beast: How emotions guide us. Basic Books.

Anscombe, E. (2000). Intention (2nd ed.). Harvard University Press.

APA. (2022). APA Dictionary of Psychology. American Psychological Association.

Armitage, R. (2021). Bullying in children: Impact on child’s health. BMJ. Paediatric Open, 5–1, 1–8.

Astor, R. A., & Benbenisthty, R. (2018). Bullying, school violence, and climate in evolving contexts: Culture, organization, and time. Oxford University Press.

Auemaneekul, N., Powwattana, A., Kiatsiri, E., & Thananowan, N. (2020). Investigating the mechanisms of theory of planned behavior on cyberbullying among Thai adolescents. Journal of Health Research, 34(1), 42–55.

Ball, H., Arseneault, L., Taylor, A., Maughan, B., Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T. (2008). Genetic and environmental influences on victims, bullies and bully-victims in childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(1), 104–112.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 33, 193–209.

Berkowitz, L. (1989). Frustration-aggression hypothesis: Examination and reformulation. Psychological Bulletin, 106(1), 59–73.

Bowes L., Arseneault L., Maughan, B., Taylor A. Caspi A., & Moffitt, T. E. (2009) School, neighborhood, and family factors are associated with children’s bullying involvement: A nationally representative longitudinal study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(5):545–553.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (2009). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Burns, S., Maycock, B., Cross, D., & Brown, G. (2008). The power of peers: Why some students bully others to conform. Qualitative Health Research, 18(12), 1704–1716.

Campaert, K., Nocentini, A., & Menesini, E. (2017). The efficacy of teachers’ responses to incidents of bullying and victimization: The mediational role of moral disengagement for bullying. Aggressive Behavior, 43, 483–492.

Connell, N. M., Morris, R. G., & Piquero, A. R. (2016). Predicting bullying: Exploring the contributions of childhood negative life experiences in predicting adolescent bullying behavior. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 60(9), 1082–1096.

Cornu, C., Abduvahobov, P., & Laoufi, R. (2022). An Introduction to a whole-education approach to school bullying: Recommendations from UNESCO scientific committee on school violence and bullying including cyberbullying. Int Journal of Bullying Prevention. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-021-00093-8

Cross, D. S., Runions, K. C., Britt, E. F., & Gray, C. (2018). Motivational interviewing as a positive response to high-school bullying. Psychology in the Schools, 55(5), 464–475.

Denti, D. (2021). Looking ahead in anger: The effects of foreign migration on youth resentment in England. Journal of Regional Science, 1–26.

Dixon, R., & Smith, P. K. (2011). Rethinking school bullying: Towards and integrated model. Cambridge University Press.

Dollard, J., Miller, N. E., Doob, L. W., Mowrer, O. H., & Sears, R. R. (1939). Frustration and aggression. Yale University Press.

Elgar, F. J., Craig, W., Boyce, W., Morgan, A., & Vella-Zarb, R. (2009). Income inequality and school bullying: Multilevel study of adolescents in 37 countries. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45, 151–159.

Espelage, D. L. (2014). Ecological theory: Preventing youth bullying, aggression, and victimization. Theory into Practice, 53(4), 257–264.

Evans, C. B. R., & Smokowski, P. R. (2016). Theoretical explanations for bullying in school: How ecological processes propagate perpetration and victimization. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal, 33(4), 365–375.

Farrell, A. H., & Volk, A. A. (2017). Social ecology and adolescent bullying: Filtering risky environments through antisocial personality. Children and Youth Services Review, 83, 85–100.

Foody, M., & Samara, M. (2018). Considering mindfulness techniques in school-based antibullying programs. Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research, 7(1), 3–9.

Fram, S. M., & Dickman, E. M. (2012). How the school-built environment exacerbates bullying and peer harassment. Children, Youth and Environmemts, 22(1), 227–249.

Georgiou, S. N., Stavrinides, P., & Fousiani, K. (2013). Authoritarian parenting, power distance, and bullying propensity. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 1(3), 199–206.

Gross, J., & Vostroknutov, A. (2022). Why do people follow social norms? Science Direct, 44, 1–6.

Hawkins, D. L., Pepler, D. J., & Craig, W. M. (2001). Naturalistic observations of peer interventions in bullying. Social Development., 10, 512–527.

Healy, K. L., & Sanders, M. R. (2014). Randomized controlled trial of a family intervention for children bullied by peers. Behavior Therapy, 45(6), 760–777.

Healy, K. L. (2020). Hypotheses for possible iatrogenic impacts of school bullying prevention programs. Child Development Perspectives., 14(4), 221–228.

Hornby, G. (2015). Bullying: An ecological approach to bullying in schools. Preventing School Failure, 60(3), 1–9.

Hymel, S., & Bonanno, R. A. (2014). Moral disengagement processes in bullying. Theory into Practice, 53(4), 278–285.

Iannello, N. M., Camodeca, M., Gelati, C., & Papotti, N. (2021). Prejudice and ethnic bullying among children: The role of moral disengagement and student-teacher relationships. Frontiers of Psychology, 12, 1–11.

Jolliffe, D., & Farrington, D. (2006). Examining the relationship between low empathy and bullying. Aggressive Behavior, 32, 540–550.

Lewin, K. (1936). Principles of topological psychology. McGraw-Hill.

Lewin, K. (1951). Reprinted 1964. Field theory in social science –selected theoretical papers by Kurt Lewin. N.Y.: Harper & Row.

Menesini, E., & Salmivalli, C. (2017). Bullying in schools: The state of knowledge and effective interventions. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 22, 240–253.

Modin, B., Laftman, S. B., & Ostberg, V. ( 2017). Teacher rated school ethos and student reported bullying–A multilevel study of upper secondary schools in Stockholm, Sweden. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14, 1–13.

Musci, R. J., Bettencourt, A. F., Sisto, B. S., Maher, B., Uhl, G., Ialongo, N., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2018). Evaluating the genetic susceptibility to peer reported bullying behaviors. Psychiatry Research, 263, 193–198.

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Blackwell.

Pabian, S., & Vandebosch, H. (2014). Using the theory of planned behavior to understand cyberbullying: The importance of beliefs for developing interventions. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 11(4), 463–477.

Perkins, H. W., Craig, D. W., & Perkins, J. M. (2011). Using social norms to reduce bullying: A research intervention among adolescents in five middle schools. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 14(5), 703–722.

Potard, C., Pochon, R., Henry, A., Combes, C., Kubiszewski, V., & Roy, A. (2021). Relationships between school bullying and frustration intolerance beliefs in adolescence: A gender-specific analysis. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy. Advance Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-021-00402-6

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Rigby, K. (1997). Attitudes and beliefs about bullying among Australian school children. Irish Journal of Psychology, 18(2), 202–220.

Rigby, K. (2012a). Bullying interventions in school: Six basic approaches. Boston/Wiley (American edition).

Rigby, K. (2012b). Bullying in schools: Addressing desires, not only behaviors. Educational Psychology Review, 24(2), 339–348.

Rigby, K. (2013). Bullying in schools and its relation to parenting and family life. Family Matters, 91, 61–68.

Rigby, K. (2021a). Addressing cases of bullying in schools: Reactive strategies. Editors: Peter K Smith and James O’Higgins. Chapter 20 In The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Bullying: A Comprehensive and International Review of Research and Intervention, 2, 370–387. London: John Wiley and Sons.

Rigby, K. (2021). Multiperspectivity in school bullying. Routledge.

Rigby, K., & Bortolozzo, G. (2013). How schoolchildren’s acceptance of self and others relate to their attitudes to victims of bullying. Social Psychology of Education, 16, 181–197.

Rigby, K., Haroun, D., & Ali, E. (2019). Bullying in schools in the United Arab Emirates and the personal safety of students. Child Indicators Research, 12, 1663–1675.

Rigby, K., & Johnson, B. (2006a). Expressed readiness of Australian school children to act as bystanders in support of children who are being bullied. Educational Psychology, 26, 425–440.

Rigby, K., & Johnson, B. (2006b). Playground heroes: Who can stop bullying? Greater Good, 14–17.

Ross, S. W., & Horner, R. H. (2009). Bully prevention in positive behavior support. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 42, 747–759.

Salmivalli, C. (2010). Bullying and the peer group: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15, 112–120.

Salmivalli, C. (2014). Participant roles in bullying: How can peer bystanders be utilized in interventions? Theory into Practice, 53(4), 286–292.

Siriporn, S. (2021). Theory of planned behavior in cyberbullying: A literature review. International Journal of Research and Review, 8(11), 234–239.

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. Simon and Schuster.

Smit, B., & Scherman, V. (2016). A case for relational leadership and an ethics of care for counteracting bullying at schools. South African Journal of Education, 36(4), 1–9.

Smith, P. K., & Sharp, S. (Eds.). (1994). School bullying: Insights and perspectives. Routledge.

Smith, P. K. (2017). Bullying and theory of mind: A review. Current Psychiatry Reviews, 13(2), 90–95.

Swearer, S. M., & Hymel, S. (2015). Understanding the psychology of bullying: Moving towards a socio-ecological diathesis- stress model. American Psychologist, 70(4), 344–355.

Tattum, D., & Tattum, E. (1992). Social education and personal development. David Fulton.

Thornberg, R., & Jungert, T. (2014). School bullying and the mechanism of moral disengagement. Aggressive. Behavior, 40, 99–108.

Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., Pozzoli, T., & Gianluca, G. (2018). Victim prevalence in bullying and its association with teacher–student and student–student relationships and class moral disengagement: A class-level path analysis. Research Papers in Education, 33(3), 320–335.

Ttofi, M. M., & Farrington, D. P. (2011). Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying: A systematic and meta-analytic review. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 7(1), 27–56.

UNESCO. (2019). School violence and bullying: Global status and trends, drivers and consequences. UNESCO.

VanGeel, M., Goemans, A., Toprak, F., & Vedder, P. (2017). Which personality traits are related to traditional bullying and cyberbullying? A study with the big five, dark triad and sadism. Personality and Individual Differences, 106(1), 231–235.

Van Ryzin, M. J., & Roseth, C. J. (2019). Effects of cooperative learning on peer relations, empathy, and bullying in middle school. Aggressive Behavior, 45(6), 643–651.

Veenstra, R., Lindenberg, S., Munniksma, A., & Dijkstra, J. K. (2010). The complex relation between bullying, victimization, acceptance, and rejection: Giving special attention to status, affection, and sex differences. Child Development, 81(2), 480–486.

Veldkamp, S. A. M., Boomsma, D. I., de Zeeuw, E. L., van Beijsterveldt, C. E. M., Bartels, M., Dolan, C. V., & van Bergen, E. (2019). Genetic and environmental influences on different forms of bullying perpetration, bullying victimization, and their co-occurrence. Behavior Genetics, 49, 432–443.

Volk, A. A., Camilleri, J. A., Dane, A. V., & Zopito, A. M. (2012). Is adolescent bullying an evolutionary adaptation? Aggressive Behavior, 38, 222–238.

Wampold, B. E. (2015). The great psychotherapy debate: The evidence for what makes psychotherapy work. Routledge.

Wei, W., Lu, J. G., Galinsky, A. D., Wu, H., Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., Yuan, W., Zhang, Q., Guo, Y., Zhang, M., Gui, W., Potter, J., Wang. J., Li, B., Xiaojie, L., Han, Y. M., Lu, M., Guo, Q., Choe, Y., Lin, W., Yu, K., Bai, Q., Shang, Z., Han, Y., & Wang, L. (2017). Regional ambient temperature is associated with human personality. Nature Human Behavior, 1(12), 890–895.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rigby, K. Theoretical Perspectives and Two Explanatory Models of School Bullying. Int Journal of Bullying Prevention 6, 101–109 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-022-00141-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-022-00141-x