Abstract

Adsorbent regeneration is critical for a continuous adsorption–regeneration process and often underestimated. In this work, the regeneration of bifunctional AgXO@SBA-15 for [O]-induced reactive adsorptive desulfurization of liquid fuel is reported and further investigated. The spent AgXO@SBA-15 was regenerated in various types of solvents followed by calcination and tested in multiple desulfurization–regeneration cycles. The effects of regenerate solvents were also compared systematically. The original and regenerated AgXO@SBA-15 was characterized by X-ray diffraction, transmission electron microscopy, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, N2 adsorption, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and atomic absorption spectrometry. The recovery of desulfurization capacity using various solvents follows the order of acetonitrile > acetone > ethanol > methanol > water. Owing to the complete reduction of silver species to Ag0 and severe agglomeration of Ag0, the bifunctional AgXO@SBA-15 demonstrating > 85% (2.60 mg-S/g) of sulfur removal dramatically reduced to < 46% (1.56 mg-S/g) after only 1st-cycle regeneration. It is suggested that polar organic species strongly adsorbed (or residual) on the spent AgXO@SBA-15, in that case, after solvent wash may contribute to the accelerated decomposition of Ag+ to Ag0 in the following calcination step. The desulfurization capacity decreased rather mildly in the later regeneration runs. Cautious choice of regeneration conditions and strategies to rational design stabilized adsorbents is required to avert the adsorbent deactivation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Environment protection is an ongoing subject worldwide and becomes even urgent with more severe air pollution nowadays. Among various air pollutants, sulfur oxide (SOx) is one typical hazard which has adverse effects on human health and the atmospheric environment (i.e., causing acid rain and generating fine particular matter) (Zhang et al. 2016b; Xia 2008; Mohammadian et al. 2017). It is estimated that half of the anthropogenic SO2 arises for the emission from fossil-fuel combustion, including on-road vehicle sources and off-road mobile sources (Lu et al. 2010; Fan et al. 2009). In such circumstances, clean fuel research, especially ultra-deep desulfurization of transportation fuels, becomes a more and more important subject in environmental catalysis. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulated a sulfur content of 30 ppmw in gasoline and 15 ppmw in diesel, and even lower sulfur content may be required in the future or for special use. Technically, refineries are facing great challenges to meet the fuel sulfur specification along with rather low operating costs and investment for ultra-deep desulfurization. Hydrodesulfurization (HDS) (Song 2003; Babich and Moulijn 2003; Song and Ma 2003) at high temperature ranging from 300 to 400 °C and high hydrogen pressure from 3 to 6 MPa converts organosulfur compounds to hydrogen sulfide (H2S) over CoMo or NiMo catalysts. Currently HDS is widely applied in refineries to remove sulfur from liquid hydrocarbon steams (Xiao et al. 2014). However, HDS achieves less efficiency in the removal of heterocyclic S-compounds such as benzothiophene (BT), dibenzothiophene (DBT) and their derivatives (González et al. 2016). Therefore, developing alternative non-hydrotreating approaches which could be used under ambient conditions and without high hydrogen consumption for effective ultra-deep desulfurization has attracted much interest (Miao et al. 2016; Sévignon et al. 2005).

Non-hydrotreating technologies, such as catalytic oxidative desulfurization (Piccinino et al. 2017; Wu et al. 2016; Li et al. 2016a, b), adsorption desulfurization (Lee and Valla 2017; Qin et al. 2016; Lei et al. 2016), biodesulfurization (Chaiprapat et al. 2015; Agarwal and Sharma 2010) and extraction desulfurization (Li et al. 2016a, b; Juliao et al. 2018; Bhutto et al. 2016) have been reported in the past decade. Among them, HDS coupled with selective adsorption of organic sulfur compounds has been considered as one potential technology (Song 2003) as HDS is efficient for desulfurization of high concentrations of organosulfur compounds, while adsorption can be advantageous for cleaning up the trace amount of stubborn organosulfur compounds which are very difficult to remove by HDS (Xiao et al. 2008, 2010). Reactive adsorptive desulfurization based on a reduced metal-based sorbent (namely S-Zorb) was developed by Phillips Petroleum and has been applied in industry (Gislason 2001). Besides, physical absorption showed advantages in easy desorption and recycling (Qiu et al. 2013; Hobson 1973), but hindered by less adsorption selectivity only targeting organosulfur compounds.

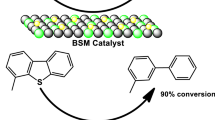

Previously, a selective catalytic adsorption desulfurization (CADS) approach coupling oxidation with adsorption for deep desulfurization was proposed (Guo et al. 2012; Li et al. 2015; Ma et al. 2007). In the CADS process, organosulfur compounds in fuels were oxidized to sulfoxides or sulfones, and then the oxidized sulfur compounds with higher polarity can be selectively adsorbed on the adsorbent surface to achieve ultra-deep desulfurization. The adsorbents served bifunctionally as an oxidation catalyst for thiophenes and as a selective adsorbent for sulfoxides/sulfones. Ren et al. (2016) investigated CADS of model diesel using TiO2/SBA-15 under mild conditions, and high desulfurization capacity of 12.7 mg-S/g was achieved even at a low sulfur concentration of 15 ppmw-S. The CADS-TiO2/SBA-15 mechanism involved the oxidation of DBT to DBTO2 by cumene hydroperoxide and the simultaneous adsorption of DBTO2 by TiO2/SBA-15. Dou and Zeng (2014) developed a synthetic route to integrate thin mesoporous silica nanowires and achieved over 99% conversion of DBT to DBTO2 in model diesel. The mesoporous silica served as catalyst and adsorbent to remove organosulfur compounds effectively. Previous work hinted that CADS via organic peroxides to convert thiophenic sulfur compounds to sulfones over adsorbent can be a plausible approach to enhance ADS selectivity for ultra-deep desulfurization. However, the high cost of organic peroxides may limit its application in industry, whereas further development of CADS processes via the abundant oxygen molecules in air can further push the way of the real applications of the CADS technology. In such case, how to activate the oxygen molecules in the air for the oxidation of thiophenes becomes critical. Xiao et al. (2013) demonstrated the desulfurization of commercial diesel by using TiO2–CeO2 mixed-oxide adsorbents with the addition of air to the fuel and found a strong promoting effect of air under ambient conditions, but the desulfurization capacity needs to be improved further. Silver nanoparticles (NPs) also possess the potential to activate oxygen molecules in the air (Le et al. 2012), while hexagonal mesoporous silica SBA-15 can serve as a promising platform for metal NPs because of its high surface area, large pore size and good stability (Dai et al. 2016; Verma et al. 2015). Beyond that, we recently demonstrated an [O]-induced reactive adsorptive desulfurization (RADS) approach using bifunctional AgXO@SBA-15 adsorbent under ambient conditions. High desulfurization capacity and selectivity, as well as a high kinetic rate for deep desulfurization, were achieved (Ye et al. 2017). However, questions remain on how to regenerate the AgXO@SBA-15 adsorbent and how it behaves in multiple runs.

In this work, the regeneration of AgXO@SBA-15 for RADS of liquid fuel was explored and further investigated. The spent AgXO@SBA-15 adsorbent was regenerated by a solvent washing followed by calcination. The effect of various solvents was compared and further discussed in detail. The original and regenerated AgXO@SBA-15 samples were characterized by N2 adsorption, powder X-ray diffraction (XRD), transmission electron microscope (TEM), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS). The deactivation mechanism of AgXO@SBA-15 during regeneration was closely investigated. The exploration of regeneration and deactivation mechanism disclosed in this work may provide guidance for cautious choice of regeneration conditions to avert the adsorbent/catalyst deactivation.

2 Experimental

2.1 Adsorbent syntheses

The supported AgXO@SBA-15 adsorbents were prepared by an incipient-wetness impregnation method assisted with ultrasound. For at least 12 h, 0.5 g SBA-15 (XFNANO Corp., China) was preheated in 110 °C. Then, 0.1545 g AgNO3 was dissolved in 1.2 mL deionized water and added into SBA-15 drop by drop with ultrasonic mixing while stirring vigorously and with the ultrasound continuing for 30 min after the deposition. After that the sample was dried at 110 °C for 2 h and calcined at 400 °C for 4 h ramped at 1.5 °C/min. The as-prepared AgXO@SBA-15 adsorbents were stored in a desiccator before use.

2.2 Model fuels

The model fuels were prepared by dissolving 150 ppmw-S of benzothiophene (BT, 99%) in n-dodecane (AR, Guangdong Guanghua Chemicals Co., 99%).

2.3 Desulfurization experiments

The desulfurization experiments were carried out in a batch reactor under ambient conditions, with 10 cc/min air flowing continuously for 4 h, and the fuel-to-sorbent ratio (w/w) was 20. And then the sulfur concentrations in initial and desulfurized fuels were analyzed by a high-performance liquid chromatogram (HPLC) equipped with a UV-Vis detector at 290 nm for BT and an ODS-C18 column at the flow rate of 1.0 cm3 min−1. In addition, the adsorption of BT over AgXO@SBA-15 without air flow was tested for comparison.

2.4 Regeneration of AgXO@SBA-15

In the regeneration process, the spent adsorbent was washed with an excess amount of acetonitrile or other solvents, including deionized water, methanol, ethanol and acetone assisted with ultrasound for 10 min and then filtered. The solid was dried in 110 °C for 30 min, and a part of the sample was stored in a desiccator before being tested in the next desulfurization cycle when another part was calcined at 400 °C for 4 h ramped at 1.5 °C/min before being stored. 15% AgXO@SBA-15 samples which were tested under the RADS system for four consecutive regeneration cycles were denoted as orig. 0, recy. 1, recy. 2, recy. 3 and recy. 4, respectively.

2.5 Characterization of AgXO@SBA-15

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD). XRD data were obtained by a Bruker D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation at room temperature with a scan speed of 2 °C/min and a step length of 0.02° at the range of 5°– 60° (2θ).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). The morphology and element mapping of the AgXO@SBA-15 samples were performed on a JEM-2100F field emission electron microscope operating at 180 kV with supplied software for automated electron tomography.

N2 adsorption. N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms were obtained at − 160 °C on a Micromeritics’ Accelerated Surface Area and Porosimetry Analyzer 2020 (ASAP 2020) equipped with commercial software for calculation and analysis. The pore textural properties such as specific Langmuir surface area and Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area were obtained by analyzing the N2 adsorption isotherms. The pressure ranges used for the BET surface area calculations were 0.05 < P/P0 < 0.25. (Based on the three consistency criteria pore volume data and pore size distribution calculation also were provided by the ASAP 2020 equipped with the software based on density functional theory (DFT).) The samples were outgassed at 186 °C for 8 h before each measurement.

Atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS). Ag loading was measured by Z-2000 AAS with 1800 line/mm diffraction raster and 200 nm wave length, 190–900 wave range. Its focal distance is 400 mm, the bottom line of the dispersion rate is 1.3 nm/mm, and spectral bandwidth has four files of 0.2, 0.4, 1.3 and 2.6. The average current value is around 2.5–20 mA.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was examined by a Kratos Axis Ultra DLD XPS spectrometer. The spectrum of each sample was recorded by monochromatized Al Kα radiation using the binding energy (284.6 eV) of amorphous C1s as the reference.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Adsorbent regeneration

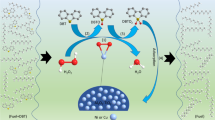

In our previous work, the bifunctional AgXO@SBA-15 adsorbent for [O]-induced reactive adsorption desulfurization (RADS) was reported, and the desulfurization capacity reached 2.62 mg-S/g with the addition of air under ambient conditions (Ye et al. 2017). The RADS mechanism of AgXO@SBA-15 illustrated that the thiophenic compounds can be oxidized to sulfones by oxidative nanosize [O]-retaining AgO on SBA-15 (the AgO transforms to Ag2O after desulfurization) in the absence of air or by the resulting or existing catalytic nanosize Ag2O and Ag (in small amounts) in the presence of air. The transformed sulfones adsorbed on the adsorbent through a stronger R2SO2-Ads H-bonding interaction through the oxygen atom in sulfones with the silanol groups on the surface of the silica support, rather than R2S-Ads interaction (Xiao et al. 2015), resulting in a dramatically enhanced ADS capacity. In this work, the adsorbent regeneration of AgXO@SBA-15 is further investigated for a continuous adsorption–regeneration process.

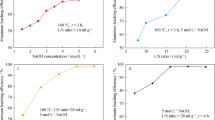

Different solvents were applied to wash the spent AgXO@SBA-15 without further calcination. Effect of solvents on RADS capacity of the spent AgXO@SBA-15 is shown in Fig. 1. By washing the spent AgXO@SBA-15 with different solvents of water, acetonitrile, methanol, ethanol and acetone, its RADS capacity recovered to 0.75, 1.12, 1.00, 1.02 and 1.10 mg-S/g, respectively. The recovery of desulfurization capacity using various solvents followed the order of acetonitrile > acetone > ethanol > methanol > water, inconsistent with the polarity of the solvents, which decreased in the order of water > acetonitrile > methanol > ethanol > acetone (Li et al. 2009). Acetonitrile showed the highest recovery, probably due to the “like dissolves like” principle as sulfone can be easily dissolved in acetonitrile, and the low surface tension enhances mass transfer (Lu et al. 2016). In the case of water, it is hard to dissolve the residual organic species from the spent AgXO@SBA-15, as sulfone cannot be dissolved in water, forming an immiscible mixture (Li et al. 2009). The pictures of the regenerated AgXO@SBA-15 after solvent wash are shown in the inset of Fig. 1. As confirmed, the acetonitrile washing showed the most similar color to the fresh material and also demonstrated the maximum recovery of desulfurization capacity. Therefore, acetonitrile was chosen as the washing solvent in the later studies.

Intended to further remove adsorbed species, i.e., sulfoxides/sulfones, thiophenic compounds, fuel compositions, residue of the polar solvent of acetonitrile on the spent AgXO@SBA-15, the adsorbent was regenerated by an acetonitrile wash followed with oxidative air treatment (Ren et al. 2016; Miao et al. 2015). Figure 2 shows the desulfurization uptakes of the 15% AgXO@SBA-15 in 4 consecutive RADS-regeneration cycles. The regenerated AgXO@SBA-15 shows the desulfurization uptakes of 2.60 (original), 1.56, 1.19, 1.06, 1.05 mg-S/g in the first four cycles, suggesting partial recovery of RADS capacity. The uptake of AgXO@SBA-15 after calcination followed by solvent washing (1.56 mg-S/g) is higher than that after solvent washing only (1.12 mg-S/g), suggesting oxidative air treatment is effective to further recover desulfurization sites on the spent AgXO@SBA-15 to some extent. It is noticeable that after the 1st-cycle regeneration, the desulfurization capacity of AgXO@SBA-15 decreased nearly 40%, yet the desulfurization capacities of AgXO@SBA-15 after the later consecutive regeneration runs decreased slightly. The results suggested that the active sites (either catalytic or adsorptive sites) on the AgXO@SBA-15 for BT catalytic oxidation adsorption cannot be fully regenerated, and the deactivation mechanism in different regeneration runs may vary. The deactivation mechanism in varied regeneration runs is worthy of further exploration.

Knowing the desulfurization capacity in the RADS process integrates adsorption capacity of BT and [O]-induced desulfurization capacity of chemically transformed sulfones (BTO2), the contributions from both parts may vary with regeneration runs. To understand the decrease in sulfur uptakes in both parts during regeneration, desulfurization under air ([O]-induced adsorptive desulfurization) and nitrogen (sole adsorptive desulfurization) was compared. Figure 3 shows the desulfurization capacity of the regenerated AgXO@SBA-15 in the 1st cycle and 4th cycle compared to the original fresh one. The original AgXO@SBA-15 showed a much lower desulfurization capacity of 1.71 mg-S/g under nitrogen (sole adsorption) than that under air ([O]-induced RADS of 2.60 mg-S/g), and the difference illustrates the contribution from the [O]-induced desulfurization. After 1st cycle of regeneration, the desulfurization capacity of AgXO@SBA-15 under air and nitrogen decreased to a similar value of ~ 1.6 mg-S/g. The results suggested the complete loss of [O]-induced desulfurization capacity only after 1-run regeneration, referred to ΔQ1 in Fig. 3. The inference was further supported by the GC–MS results, as only BT was detected on the spent AgXO@SBA-15 under air, and no sulfone was detected either in the eluent (acetonitrile solvent after washing the spent sorbent) or in the treated fuel. It should be mentioned that after losing the [O]-induced desulfurization capacity in the 1st run, the adsorption capacity decreased much more mildly (referred to ΔQ2 in Fig. 3) even after multiple regeneration runs. The loss of [O]-induced desulfurization capacity may relate to the irreversible loss of the oxidation or catalytic oxidation sites on SBA-15, i.e., nanosize AgO, AgO2 and Ag particles, while the loss of adsorption capacity of BT may be caused by the damaged or reduced amount of adsorption sites, which will be further characterized in the next session.

Desulfurization capacity over AgXO@SBA-15 original and recycled samples under air and nitrogen. (ΔQ1: complete loss of [O]-induced desulfurization capacity after 1-run regeneration. ΔQ2: mild decrease in adsorption capacity. Reaction conditions: fuel-to-sorbent ratio of 20:1 (w/w), fuel of 150 ppmw-S BT in n-dodecane, air and nitrogen bubbled in at ambient condition)

3.2 Sorbent characterizations

Figure 4a, b shows the wide and low-angle XRD patterns of AgXO@SBA-15 samples at four consecutive RADS-regeneration cycles. No intense diffraction peaks of silver species were detected on the fresh AgXO@SBA-15, indicating high dispersion of silver nanoparticles. The particle size of AgXO is calculated to be 3–4 nm (by TEM in Fig. 5), below the detection limit of the XRD instrument, as reported in the literature (Zhang et al. 2016a; Perkas et al. 2013). In sharp contrast, two diffraction peaks at 38.1° and 44.1° appeared in all of the regenerated samples, corresponding to the reflections of (111) and (200) crystalline planes of face-centered cubic (fcc) structure of metallic Ag0 (JCPDS Card No. 04-0783) (Gu et al. 2011). The results indicated that the multivalent silver nanoparticles reduced to zero-valence Ag0 after oxidative air treatment. Moreover, the XRD results suggested that the particle size of silver increased after regeneration. It should be noticed that the diffraction intensity of both peaks increased with increasing runs of regeneration. The Scherrer equation (Borchert et al. 2005; Ocakoglu et al. 2015) \(D = 0.89\lambda /\beta \cos \theta\) was used to calculate the crystalline size (D) of the recycled AgXO@SBA-15, where λ, β and θ were X-ray wavelength, FWHM of diffraction peak and Bragg’s diffraction angle, respectively. Instrumental broadening was taken into account in the calculation, and the result is listed in Table 1. Based on the FWHM of Ag(111) diffraction peaks at 0.295°, 0.284°, 0.280° and 0.269°, the crystalline sizes of the Ag particles in 1–4 runs became 27.2, 28.5, 28.7 and 30.1 nm, respectively. The data indicated that the silver particles sharply aggregated from the average particle size of ~ 3 to ~ 27 nm after 1st-cycle regeneration, and further increased slightly after the latter runs of regeneration.

From the low-angle XRD patterns, the three peaks at 2θ of 0.92°, 1.60° and 1.84° were corresponding to (100), (110), (200) planes of the hexagonal mesostructure (Dai et al. 2016), respectively. The results suggested that the hexagonal order was well maintained, but slight loss of peak intensity for the low-angle reflections was observed after multiple runs of regeneration. It was noticed that the diffraction peaks of the initial AgXO@SBA-15 samples shifted to higher angle in the recycled AgXO@SBA-15 samples, indicating the decrease in SBA-15 lattice parameters after oxidative air treatment. Table 1 lists the interplanar spacings d100 and the unit cell parameter a0 of AgXO@SBA-15 in multiple runs of regeneration. Slight decrease in d100 (from 9.6 to 9.3 nm after 4 runs) and a0 (from 11.1 to 10.7 after 4 runs) can be found, and it further suggested that the mesoporous structure of AgXO@SBA-15 nanocomposites showed unit cell shrinkage (Ebin et al. 2010; Aronson et al. 1997) with the increase in regeneration cycles. It is believed that the oxidative air treatment introduced defects that can lead to slight contraction of the framework. This framework contraction may result from further silver condensation during regeneration.

To complement the XRD analysis, transmission electron microscope (TEM) and energy-dispersive X-Ray spectroscopy (EDS) were employed to directly observe the change on Ag crystalline particles of AgXO@SBA-15. Figure 5a-1, a-2 shows the TEM image of the fresh AgXO@SBA-15. Multivalent silver nanoparticles were detected and dispersed homogeneously in the channel of SBA-15 supports. The spherical nanoparticles possess d-spacing of 0.241, 0.216, 0.233 and 0.205 nm, corresponding to the (111) and (213) planes of AgO, (101) plane of Ag2O and (200) plane of Ag, respectively. The corresponding EDS elemental mapping (Fig. 5a-3) shows that the Ag species is well dispersed in the fresh sample. The particle-size histogram (Fig. 5a-4) reveals that the particle size of Ag nanoparticles displays a normal distribution, and their average size is 1.65 ± 1.17 nm. In contrast, the images of AgXO@SBA-15 after 1st-cycle regeneration (Fig. 5b-1, b-2) reveal that the Ag nanoparticles agglomerated to quite large spherical particles. The particles possess d-spacing of 0.205 and 0.232 nm, corresponding to the (200) and (111) planes of Ag0, respectively, with the particle size of silver species as large as 50.6 ± 8.7 nm. The particle size detected by TEM is much larger than the calculated value from XRD, because the particle size calculated by Scherrer equation is the average size of silver particles and the silver particles on the surface of AgXO@SBA-15 detected by TEM are partially agglomerated, as reported in the literature (Ebin et al. 2010). Besides, the corresponding EDS elemental mapping (Fig. 5b-3) reveals that the silver particles on AgXO@SBA-15 are partly aggregated after regeneration. And silver clusters further aggregated to larger silver particles of 52.3 ± 13.5 nm after four continuous regeneration cycles (Fig. 5c-1, c-2). Corresponding EDS (Fig. 5c-3) showed the silver particles aggregated more intuitively.

From the result of XRD and TEM/EDS, a conjecture is that the desulfurization capacity decreased sharply after the 1st-cycle regeneration because the active high-valence AgO and Ag2O were reduced to zero-valence Ag0 and the metallic silver nanoparticles aggregated to bigger ones which resulted in the complete loss of [O]-induced desulfurization capacity of AgXO@SBA-15. The presence of Ag0 in regenerated samples was further confirmed in XPS (Fig. 6), though Ag0 was also detected in the fresh sample via XPS, which was attributed to the fact that nanosize silver species in AgXO@SBA-15 are readily reduced to the elemental Ag0 at high vacuum (10−7 Pa for 6 h pretreatment in XPS, as stated in our previous work) (Ye et al. 2017). In the latter regeneration runs, the desulfurization capacity decreased slightly, because the mild aggregation of Ag0 particles resulted in a gentle decrease in adsorption capacity of BT.

From our previous work, the optimized adsorption configurations of the possible functionalities of Ag0, Ag2O and surface silanol group Si–OH were calculated (Le et al. 2012). The fresh AgXO@SBA-15 and, in the presence of air, BT were transferred to BTO2 by oxidative AgO or oxygen catalyzed by Ag2O. In this case, BTO2 has a shorter bond with Si–OH (2.01 Å) than Ag (2.72 Å) or Ag2O (2.75 Å), suggesting BTO2 preferentially adsorbs on Si–OH, which explains the enhanced desulfurization capacity after RADS. On the other hand, the bond distance for BT follows the order of Ag2O (2.39 Å) < Ag (2.65 Å) < Si–OH (3.43 Å), suggesting BT adsorbs on silver sites preferentially. Hence, in the RADS system, the affinity between the adsorbents and adsorbates follows the order of BTO2–(Si–OH) > BT–Ag2O > BT–Ag > BTO2–Ag > BTO2–Ag2O > BT–(Si–OH). The strong affinity of BTO2–(Si–OH) resulted in the high desulfurization capacity of the fresh AgXO@SBA-15. However, after the regeneration of AgXO@SBA-15, the major silver species presented on SBA-15 is non-oxidative and bulky Ag0. On the one hand, the dominant adsorbent–adsorbate affinity transferred from strong BTO2–(Si–OH) through [O]-induced desulfurization to relative weak BT–Ag0 interaction through pi-complexation. On the other hand, from the result of XRD (Fig. 4) and TEM (Fig. 5), the severe agglomeration of silver species is detected, that is to say, the amount of exposed adsorption sites of Ag0 on SBA-15 for BT also decreased, resulting in dramatically decreased desulfurization capacity after regeneration.

Figure 7a, b shows the nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms and the corresponding pore width distribution of AgXO@SBA-15 at four consecutive RADS-regeneration cycles referred to the SBA-15 substrate, with the textural properties as listed in Table 1. According to the IUPAC classification (Malakooti et al. 2013), the nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms of SBA-15 and AgXO@SBA-15 original and recycled samples belong to typical IV isotherms, suggesting that all the support SBA-15 and AgXO@SBA-15 samples after regeneration retain mesoporosity with two-dimensional hexagonal structures (George et al. 2005). However, Type H1 loops are observed on the AgXO@SBA-15, while an H2 hysteresis loop is observed in SBA-15 (Kruk and Jaroniec 2001). In fact, an H1 hysteresis loop was often reported for the materials that consisted of agglomerates or compacts of approximately spherical particles arranged in a fairly uniform way (Sing et al. 1985), and H2 hysteresis loops were observed for materials with relatively uniform channel-like pores (Kruk and Jaroniec 1997), which correspond to the silver impregnation and agglomeration after regeneration of AgXO@SBA-15 and mesoporous channels of SBA-15, respectively. Meanwhile, the adsorbed N2 amounts decreased after loading AgXO on SBA-15, but only a gentle decline was observed in AgXO@SBA-15 in four consecutive regenerations, suggesting that the porosity of AgXO@SBA-15 remained almost the same with only a slight decline.

As shown in Table 1, SBET of SBA-15 and AgXO@SBA-15 in multiple runs is 723.6, 489.2, 473.7, 447.0, 428.9 and 413.2 m2/g, respectively. BET surface area decreased sharply after silver impregnation and only slightly after regenerations. A similar trend was observed in the decrease in pore volumes of SBA-15 and AgXO@SBA-15 in multiple runs, corresponding to 1.15, 0.72, 0.72, 0.69, 0.68 and 0.66 cm2/g, respectively. Considering that both the SBET and the sulfur adsorption capacity decrease gradually, a linear fitting between SBET and sulfur adsorption capacity is presented in Fig. 8. Except the fresh AgXO@SBA-15, sulfur adsorption capacity (Q) decreases with SBET of AgXO@SBA-15 in latter runs of regeneration, which can be fitted to Q = 0.0087 × SBET–2.62 with correlation coefficients (R2) of 0.84. The decreased SBET in multiple runs can be associated with the agglomeration of silver particles, while retaining similar pore sizes (Fig. 7b).

Metal leaching is another concern for multirun regeneration, which was studied with AAS (Butler et al. 2015). Silver content of AgXO@SBA-15 in multiple runs was measured as 15.0%, 15.2%, 15.4%, 15.5% and 15.6%, respectively (Fig. 9), suggesting no leaching of silver species after cycles of regeneration. It can be noted that the silver amount even increased slightly after cycles of regenerations. One conceivable explanation is the reduction of AgO/Ag2O on the fresh sample to metallic Ag0 of AgXO@SBA-15, resulting in the loss of oxygen atoms, and the decrease in the background denominator, so the overall content of Ag element increased. Theoretically, the complete reduction of AgO and Ag2O to Ag would result in the increase in Ag content to 15.7% and 15.3%, respectively (Zvereva and Trunova 2012).

From the above analysis, the deactivation mechanism of AgXO@SBA-15 after regeneration can be deduced. After the 1st-cycle regeneration, high-valence AgO/Ag2O reduced to zero-valence Ag0 after oxidative air treatment, and much larger aggregated Ag0 particles, resulting in the complete loss of oxidation capacity of AgXO@SBA-15, and the affinity between the adsorbates and adsorbents decreased. Meanwhile, the adsorption affinities as well as the amount of adsorption sites decreased after 1st cycle of regeneration, resulting in sharply decreased desulfurization capacity. In the latter regeneration cycles, the further aggregation of Ag0 particles and the mild decrease in SBET of AgXO@SBA-15 resulted in the gradual slight decrease in the desulfurization capacity in the latter regenerations. Nevertheless, the specific factors leading to the reduction or agglomeration is worthy to be further explored.

3.3 Effect of regeneration steps

Considering the severe deactivation of AgXO@SBA-15 in the first regeneration, further work was carried out to ascertain which step or steps in regeneration made the deactivation occur. Figure 10a shows the desulfurization capacity of AgXO@SBA-15 samples with different regeneration treatments, and corresponding XRD patterns of the resulting samples are shown in Fig. 10b. The regenerated sample was tested in desulfurization under air and nitrogen, and their sulfur capacities are 1.12 mg-S/g and 0.87 mg-S/g, respectively. The one under air exhibited higher desulfurization capacity than that under nitrogen, suggesting portion of catalytic sites for sulfur oxidation recovered after the acetonitrile solvent washing. The corresponding XRD patterns (sample solvent wash) show that no Ag diffraction peak was detected, indicating that individual operation of a solvent washing would not lead to the agglomeration of silver particles. However, the solvent itself is likely to remain and block the active sites on the adsorbent surface, resulting in reduced desulfurization capacity. Hence, the step of followed-up calcination is necessary to remove the residual species in common regeneration. However, the desulfurization capacity recovered only 46% after calcination (1.56 mg-S/g), indicating that AgXO@SBA-15 deactivated during calcination. To rule out the possibility of the deactivation of AgXO@SBA-15 in longer calcination time, the re-calcination of the fresh AgXO@SBA-15 sample without desulfurization test (sample re-calcine) was conducted and the desulfurization capacity reached up to 2.52 mg-S/g, 97% of the desulfurization capacity of the AgXO@SBA-15 fresh sample, suggesting that the loss of desulfurization capacity may not relevant with the calcination time of AgXO@SBA-15.

In fact, well-dispersed Ag2O and nanosize Ag can be observed after desulfurization from the result of TEM (Le et al. 2012), which ruled out the possibility of the reduction and agglomeration of silver particles during desulfurization. In the meantime, the corresponding XRD patterns of AgXO@SBA-15 samples with different regeneration treatments show that no Ag diffraction peak was detected in the sample solvent wash and re-calcine, indicating that neither individual operation of solvent wash nor calcination contributes to the agglomeration of silver particles. It is likely that the decomposition and agglomeration of Ag+ to Ag0 may occur during the thermal regeneration step, only in the presence of the polar organic compounds remaining on the AgXO@SBA-15 after solvent washing, as silver/silver oxide attracts N-containing organic solvents easily, i.e., ammonia solutions or cupric ammine (Starovoytov et al. 2007; Guan 1994; Yoon et al. 2003), which further accelerates the reductive decomposition of silver species, and the Ag0 is more likely to accumulate on the silica surface. For comparison, instead of organic solvents, the desulfurization capacity of the spent adsorbent regenerated by deionized water wash followed with oxidative air treatment was tested and the desulfurization capacity was only 0.83 mg-S/g, lower than that from acetonitrile. This is likely due to the fact that water can hardly remove the residues adsorbed on the spent AgXO@SBA-15. Therefore, the choice of regeneration solvent must be cautious and is under further investigation.

Figure 11 shows the schematic diagram of the deactivation mechanism of AgXO@SBA-15. In the process of RADS, the active high-valence AgO oxidized BT in the model fuel and as well the Ag2O species also acted as the oxidation catalyst to transform BT into BTO2 in air. As the transformed BTO2 has a stronger affinity for AgXO@SBA-15 than BT, thus BTO2 and a small amount of BT were adsorbed onto AgXO@SBA-15 through BTO2–(Si–OH) or BT–Ag2O interaction, etc. After desulfurization, the active high-valence AgO was consumed, and more Ag2O and a small amount of Ag0 were present well dispersed on the surface of the spent AgXO@SBA-15, as shown in Fig. 11a. In the first step of solvent washing in regeneration, BTO2 and BT, some organic compounds (as shown as “residue” in Fig. 11) as well as alkanes, the alcohols by-products and the washing solvent itself (acetonitrile), etc., may be residual or adsorbed on the spent AgXO@SBA-15 after solvent washing (Fig. 11b), which also blocked the active sites on AgXO@SBA-15 for completely reversible RADS. As shown in Fig. 11c, with the surrounding organic species over AgXO@SBA-15, the decomposition of Ag2O accelerates and the agglomeration of Ag0 occurs during calcination up to 400 °C.

4 Conclusion

The regeneration of AgXO@SBA-15 for fuel desulfurization was investigated in this study. The recovery of desulfurization capacity using various solvents follows the order of acetonitrile > acetone > ethanol > methanol > water. It was noticeable that after the 1st-run regeneration, the desulfurization uptake of AgXO@SBA-15 decreased to 46% (1.56 mg-S/g), but the decrease is much milder in the latter regenerations. The deactivation mechanism in multiple cycles and during each regeneration step was further examined. XRD and TEM results suggested that high-valence AgO/Ag2O in the fresh AgXO@SBA-15 altered to zero-valence Ag0 after the 1st-run regeneration and aggregation of nanosize silver particles occurred, resulting in the complete loss of oxidizability of Ag species that oxidize BT to the corresponding sulfones with high adsorption affinity to the AgXO@SBA-15. Polar organic compounds strongly adsorbed (residual) on the spent AgXO@SBA-15 after solvent washing may contribute to the decomposition of Ag+ to Ag0 and silver aggregation during the second thermal regeneration step. Further mild aggregation of Ag0 particles and gentle decrease in SBET of AgXO@SBA-15 were noted in the regenerated AgXO@SBA-15 in the latter cycles, which likely contribute to the gradual decrease in adsorption capacity of BT. Cautious choice of regeneration conditions and strategies to rational design stabilized adsorbents may reduce the adsorbent deactivation.

References

Agarwal P, Sharma DK. Comparative studies on the bio-desulfurization of crude oil with other desulfurization techniques and deep desulfurization through integrated processes. Energy Fuels. 2010;24(1):518–24. https://doi.org/10.1021/ef900876j.

Aronson BJ, Blanford CF, Stein A. Solution-phase grafting of titanium dioxide onto the pore surface of mesoporous silicates: synthesis and structural characterization. Chem Mater. 1997;9(12):2842–51. https://doi.org/10.1021/cm970180k.

Babich IV, Moulijn JA. Science and technology of novel processes for deep desulfurization of oil refinery streams: a review. Fuel. 2003;82(6):607–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-2361(02)00324-1.

Bhutto AW, Abro R, Gao S, Abbas T, Chen X, Yu G. Oxidative desulfurization of fuel oils using ionic liquids: a review. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng. 2016;62:84–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtice.2016.01.014.

Borchert H, Shevchenko EV, Robert A, Mekis I, Kornowski A, Grübel G. Determination of nanocrystal sizes: a comparison of TEM, SAXS, and XRD studies of highly monodisperse CoPt3 particles. Langmuir. 2005;21:1931–6. https://doi.org/10.1021/la0477183.

Butler OT, Cairns WRL, Cook JM, Davidson CM. 2014 atomic spectrometry update—a review of advances in environmental analysis. J Anal At Spectrom. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1039/c4ja90062f10.1039/c4ja90062f.

Chaiprapat S, Charnnok B, Kantachote D, Sung S. Bio-desulfurization of biogas using acidic biotrickling filter with dissolved oxygen in step feed recirculation. Bioresour Technol. 2015;179:429–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2014.12.068.

Dai P, Yan TT, Yu XX, Bai ZM, Wu MZ. Two-solvent method synthesis of NiO/ZnO nanoparticles embedded in mesoporous SBA-15: photocatalytic properties study. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2016;11(1):226. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-016-1445-2.

Dou J, Zeng HC. Integrated networks of mesoporous silica nanowires and their bifunctional catalysis-sorption application for oxidative desulfurization. ACS Catal. 2014;4(2):566–76. https://doi.org/10.1021/cs400996j.

Fan Q, Zhao D, Dai Y. The research of ultra-deep desulfurization in diesel via ultrasonic irradiation under the catalytic system of H2O2–CH3COOH–FeSO4. Pet Sci Technol. 2009;27(3):302–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10916460701707679.

George J, Shylesh S, Singh AP. Vanadium-containing ordered mesoporous silicas: synthesis, characterization and catalytic activity in the hydroxylation of biphenyl. Appl Catal A Gen. 2005;290:148–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcata.2005.05.012.

Gislason J. Phillips sulfur-removal process nears commercialization. Oil Gas J. 2001;99(47):72.

González J, Chen LF, Wang JA, Manríquez M, Limas R, Schachat P, et al. Surface chemistry and catalytic properties of VOX/Ti-MCM-41 catalysts for dibenzothiophene oxidation in a biphasic system. Appl Surf Sci. 2016;379:367–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.04.067.

Gu G, Xu J, Wu Y, Chen M, Wu L. Synthesis and antibacterial property of hollow SiO2/Ag nanocomposite spheres. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2011;359(2):327–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2011.04.002.

Guan Y. The dissolution behavior of silver in ammoniacal solutions with cupric ammine. J Electrochem Soc. 1994;141(1):91–6. https://doi.org/10.1149/1.2054715.

Guo J, Janik MJ, Song C. Density functional theory study on the role of ceria addition in TixCe1−xO2 adsorbents for thiophene adsorption. J Phys Chem C. 2012;116(5):3457–66. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp2063996.

Ebin B, Yazici E, Gurmen S, Ozkal B. Preparation and characterization of nanocrystalline silver particles. TMS Annual Meeting. 2010:571–576.

Hobson JP. Physical adsorption. Crit Rev Solid State Mater Sci. 1973;4(1–4):221–45.

Juliao D, Gomes AC, Pillinger M, Valenca R, Ribeiro JC, Goncalves IS, et al. Desulfurization of liquid fuels by extraction and sulfoxidation using H2O2 and [CpMo(CO)3R] as catalysts. Appl Catal B Environ. 2018;230:177–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.02.036.

Kruk M, Jaroniec M. Application of large pore MCM-41 molecular sieves to improve pore size analysis using nitrogen adsorption measurements. Langmuir. 1997;13(23):6267–73. https://doi.org/10.1021/la970776m.

Kruk M, Jaroniec M. Gas adsorption characterization of ordered organic-inorganic nanocomposite materials. Chem Mater. 2001;13(10):3169–83. https://doi.org/10.1021/cm0101069.

Le Y, Mehmood F, Lee S, Greele J, Lee B, Seifert S, et al. Increased silver activity for direct propylene epoxidation via subnanometer size effects. Science. 2012;328(5975):224–8. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1185200.

Lee KX, Valla JA. Investigation of metal-exchanged mesoporous Y zeolites for the adsorptive desulfurization of liquid fuels. Appl Catal B. 2017;201:359–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2016.08.018.

Lei W, Wenya W, Mominou N, Liu L, Li S. Ultra-deep desulfurization of gasoline through aqueous phase in situ hydrogenation and photocatalytic oxidation. Appl Catal B. 2016;193:180–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2016.04.032.

Li JR, Kuppler RJ, Zhou HC. Selective gas adsorption and separation in metal-organic frameworks. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38(5):1477–504. https://doi.org/10.1039/b802426j.

Li LD, Xu CZ, Zheng MQ, Chen XH. Effect of B2O3 modified Ag/TiO2–Al2O3 adsorbents on the adsorption desulfurization of diesel. J Fuel Chem Technol. 2015;43(8):990–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1872-5813(15)30028-1.

Li M, Zhou Z, Zhang F, Chai W, Zhang L, Ren Z. Deep oxidative-extractive desulfurization of fuels using benzyl-based ionic liquid. AIChE J. 2016a;62(11):4023–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/aic.15326.

Li S-W, Gao R-M, Zhang R-L, Zhao JS. Template method for a hybrid catalyst material POM@MOF-199 anchored on MCM-41: highly oxidative desulfurization of DBT under molecular oxygen. Fuel. 2016b;184:18–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2016.06.132.

Lu Z, Streets DG, Zhang Q, Wang S, Carmichael GR, Cheng YF, et al. Sulfur dioxide emissions in China and sulfur trends in East Asia since 2000. Atmos Chem Phys. 2010;10(13):6311–31. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-10-6311-2010.

Lu Z, Guo E, Zhong H, Tian Y, Yao Y, Lu S. Kinetic modeling of the extraction-oxidation coupling process for the removal of dibenzothiophene. Energy Fuels. 2016;30(9):7214–20. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.6b01552.

Ma X, Zhou A, Song C. A novel method for oxidative desulfurization of liquid hydrocarbon fuels based on catalytic oxidation using molecular oxygen coupled with selective adsorption. Catal Today. 2007;123(1–4):276–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2007.02.036.

Malakooti R, Parsaee Z, Hosseinabadi R, Oskooie HA, Heravi MM, Saeedi M, et al. [Cu(bpdo)2·2H2O]2+-supported SBA-15 nanocatalyst for efficient one-pot synthesis of benzoxanthenone and benzochromene derivatives. C R Chim. 2013;16(9):799–806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crci.2013.03.007.

Miao G, Ye F, Wu L, Ren X, Xiao J, Li Z, et al. Selective adsorption of thiophenic compounds from fuel over TiO2/SiO2 under UV-irradiation. J Hazard Mater. 2015;300:426–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.07.027.

Miao G, Huang D, Ren X, Li X, Li Z, Xiao J. Visible-light induced photocatalytic oxidative desulfurization using BiVO4/C3N4@SiO2 with air/cumene hydroperoxide under ambient conditions. Appl Catal B. 2016;192:72–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2016.03.033.

Mohammadian M, Ahmadi M, Khosravinikou MR. Adsorptive desulfurization and denitrogenation of model fuel by mesoporous adsorbents (MSU-S and CoO-MSU-S). Pet Sci Technol. 2017;35(6):608–14.

Ocakoglu K, Mansour ShA, Yildirimcan S, Al-Ghamdi AA, El-Tantawy F, Yakuphanoglu F. Microwave-assisted hydrothermal synthesis and characterization of ZnO nanorods. Spectrochim Acta Part A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2015;148:362–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2015.03.106.

Perkas N, Lipovsky A, Amirian G, Nitzan Y, Gedanken A. Biocidal properties of TiO2 powder modified with Ag nanoparticles. J Mater Chem B. 2013;1(39):5309. https://doi.org/10.1039/c2tb00337f.

Piccinino D, Abdalghani I, Botta G, Crucianelli M, Passacantando M, Di Vacri ML, et al. Preparation of wrapped carbon nanotubes poly(4-vinylpyridine)/MTO based heterogeneous catalysts for the oxidative desulfurization (ODS) of model and synthetic diesel fuel. Appl Catal B. 2017;200:392–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2016.07.037.

Qin J-X, Tan P, Jiang Y, Liu X-Q, He Q-X, Sun L-B. Functionalization of metal–organic frameworks with cuprous sites using vapor-induced selective reduction: efficient adsorbents for deep desulfurization. Green Chem. 2016;18(11):3210–5. https://doi.org/10.1039/c6gc00613b.

Qiu L, Zou K, Xu G. Investigation on the sulfur state and phase transformation of spent and regenerated S zorb sorbents using XPS and XRD. Appl Surf Sci. 2013;266:230–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2012.11.156.

Ren X, Miao G, Xiao Z, Ye F, Li Z, Wang H, et al. Catalytic adsorptive desulfurization of model diesel fuel using TiO2/SBA-15 under mild conditions. Fuel. 2016;174:118–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2016.01.093.

Sévignon M, Macaud M, Favre-Réguillon A, Schulz J, Rocault M, Faure R, et al. Ultra-deep desulfurization of transportation fuels via charge-transfer complexes under ambient conditions. Green Chem. 2005;7(6):413. https://doi.org/10.1039/b502672e.

Sing KSWE, Everett DH, Haul RAW, Moscou L, Pierotti RA, Rouquerol J, Siemieniewska T. Reporting physisorption data for gas/solid systems with special reference to the determination of surface area and porosity. Pure Appl Chem. 1985;57(11):603–19.

Song C. An overview of new approaches to deep desulfurization for ultra-clean gasoline, diesel fuel and jet fuel. Catal Today. 2003;86(1–4):211–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0920-5861(03)00412-7.

Song C, Ma X. New design approaches to ultra-clean diesel fuels by deep desulfurization and deep dearomatization. Appl Catal B. 2003;41(1–2):207–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0926-3373(02)00212-6.

Starovoytov ON, Kim NS, Han KN. Dissolution behavior of silver in ammoniacal solutions using bromine, iodine and hydrogen-peroxide as oxidants. Hydrometallurgy. 2007;86(1–2):114–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hydromet.2006.11.009.

Verma P, Kuwahara Y, Mori K, Yamashita H. Synthesis and characterization of a Pd/Ag bimetallic nanocatalyst on SBA-15 mesoporous silica as a plasmonic catalyst. J Mater Chem A. 2015;3(37):18889–97. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5ta04818d.

Wu P, Zhu W, Dai B, Chao Y, Li C, Li H, et al. Copper nanoparticles advance electron mobility of graphene-like boron nitride for enhanced aerobic oxidative desulfurization. Chem Eng J. 2016;301:123–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2016.04.103.

Xia D. The oxidation-extraction desulfurization of FCC gasoline. Pet Sci Technol. 2008;26(16):1887–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/10916460701426072.

Xiao J, Li Z, Liu B, Xia Q, Yu M. Adsorption of benzothiophene and dibenzothiophene on ion-impregnated activated carbons and ion-exchanged Y zeolites. Energy Fuels. 2008;22(6):3858–63. https://doi.org/10.1021/ef800437e.

Xiao J, Bian G, Zhang W, Li Z. Adsorption of dibenzothiophene on Ag/Cu/Fe-supported activated carbons. J Chem Eng Data. 2010;55(12):5818–23. https://doi.org/10.1021/je1007795.

Xiao J, Sitamraju S, Chen Y, Janik M, Song C. Air-promoted adsorptive desulfurization over Ti0.9Ce0.1O2 mixed oxides from diesel fuel under ambient conditions. ChemCatChem. 2013;5(12):3582–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/cctc.201300329.

Xiao J, Wu L, Wu Y, Liu B, Dai L, Li Z, et al. Effect of gasoline composition on oxidative desulfurization using a phosphotungstic acid/activated carbon catalyst with hydrogen peroxide. Appl Energy. 2014;113:78–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2013.06.047.

Xiao J, Sitamraju S, Chen Y, Watanabe S, Fujii M, Janik M, et al. Air-promoted adsorptive desulfurization of diesel fuel over Ti-Ce mixed metal oxides. AIChE J. 2015;61(2):631–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/aic.14647.

Ye FMG, Wu Y, Li Z, Song CS, Xiao J. [O]-induced reactive adsorptive desulfurization of fuel over AgXO@SBA-15 under ambient conditions. Chem Eng Sci. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2017.04.032.

Yoon H, Sohn JS, Kim NS, Han KN. Dissolution behavior of silver/silver oxides in ammoniacal solutions. Miner Metall Process. 2003;20(1):31–5.

Zhang X, Dong H, Zhao D, Wang Y, Wang Y, Cui L. Effect of support calcination temperature on Ag structure and catalytic activity for CO oxidation. Chem Res Chin Univ. 2016a;32(3):455–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40242-016-5377-2.

Zhang Y, Yuan S, Feng X, Li H, Zhou J, Wang B. Preparation of nanofibrous metal-organic framework filters for efficient air pollution control. J Am Chem Soc. 2016b;138(18):5785–8. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.6b02553.

Zvereva VV, Trunova VA. Determination of the elemental composition of tissues of the cardiovascular system by atomic spectrometry, mass spectrometry and X-ray spectrometry methods. J Anal Chem. 2012;67(7):613–31. https://doi.org/10.1134/s1061934812070064.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the research grants provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21576093), Guangdong Natural Science Funds for Distinguished Young Scholars (2016A030306031), Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (2014A030312007) and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Edited by Xiu-Qin Zhu

Handling editor: Wen shuai Zhu

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, L., Ye, F., Lei, D. et al. Regeneration of AgXO@SBA-15 for reactive adsorptive desulfurization of fuel. Pet. Sci. 15, 857–869 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12182-018-0264-8

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12182-018-0264-8