Abstract

This paper evaluates Peter Klein’s objection to foundationalism. According to Klein, foundationalism fails because it allows arbitrariness “at the base.” I first explain that this objection can be interpreted in two ways: either as targeting dialectical foundationalism or as targeting epistemic foundationalism. I then clarify Klein’s concept of arbitrariness. An assertion or belief is assumed to be arbitrary if and only if it lacks a reason that is “objectively and subjectively available.” Drawing on this notion, I evaluate Klein’s objection. I first argue that his objection construed as targeting dialectical foundationalism fails, since nothing prevents dialectical foundationalism from ruling out arbitrary assertions. I then argue that the objection seen as targeting epistemic foundationalism cannot be disqualified in the way some foundationalists believe. However, I show that also the objection so construed does not succeed, since epistemic foundationalism need not countenance arbitrary beliefs.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction: Foundationalism and the Arbitrariness Objection

Foundationalism, as a theory of epistemic justification, has met with a variety of objections. It has been criticized for positing incorrigible beliefs, or infallible beliefs, or beliefs that are justified merely in virtue of someone’s holding them. As has been convincingly argued, though, foundationalism can be defended as a view that does not posit such beliefs (e.g., Alston 1976b). A different, and possibly more subtle, objection states that foundationalism, in holding that at some point chains of justification come to an end, allows a kind of arbitrariness. This objection to foundationalism can be found at several places but has been put forward most explicitly and forcefully in some recent papers by Peter Klein. According to Klein,

In the present paper, I argue that Klein’s objection does not succeed. However, I also explain that the responses given by several foundationalists fail to show that Klein is wrong. I proceed as follows. In Section 2, I distinguish two versions of foundationalism: dialectical foundationalism and epistemic foundationalism. I explain that many of Klein’s remarks appear to be directed at dialectical foundationalism, but that there are also indications that he objects to epistemic foundationalism. In Section 3, I explain Klein’s concept of arbitrariness. An assertion or belief is assumed to be arbitrary if and only if it lacks a reason that is “objectively and subjectively available.” Drawing on this notion, I evaluate Klein’s objection in Section 4 and Section 5. In Section 4, I discuss the objection construed as an objection to dialectical foundationalism. I argue that this objection fails, since dialectical foundationalism can be defended as a view that licenses only assertions which have an objectively and subjectively available reason. In Section 5, I assess Klein’s objection as an objection to epistemic foundationalism. I argue that, so construed, it cannot be shown to be mistaken in the way some foundationalists believe. However, at the same time, I show that also epistemic foundationalism need not allow arbitrariness. Since it is possible to construe basic beliefs such that they should have a reason that is objectively and subjectively available, epistemic foundationalism can rule out arbitrary beliefs.

2 Klein’s Objection to Foundationalism

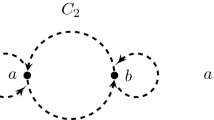

Foundationalism is typically seen as a response to the regress problem. This problem admits of at least two varieties: an epistemic regress problem and a dialectical regress problem. The epistemic regress problem arises on the assumptions that a belief can only be justified if it is based on a reason or ground and that reasons or grounds are further justified beliefs. If a belief B1 can only be justified by another justified belief B2, and B2 can only be justified by a further justified belief B3, which can only be justified by a still further justified belief B4, etc., this implies that in order to have any justified belief, we need to have infinitely many justified beliefs.

The dialectical regress problem, on the other hand, arises in situations where a person is asked to justify her belief in response to critical challenges. Suppose S believes that p, and an interlocutor asks her to give a reason for thinking p is true. After S responds by saying that q, the interlocutor asks for a reason for believing q. When S answers by asserting that r, the interlocutor asks for a reason for r. If S’s interlocutor is what Leite (2005) has called a “persistent interlocutor,” one who never stops asking for reasons, and if S is obliged to give reasons whenever challenged to do so, it seems that she has to be able to cite reasons indefinitely.

Rescorla (2009, pp. 44–46) has shown that since there is this distinction between an epistemic regress problem and a dialectical regress problem, a distinction should be drawn between two forms of foundationalism as well. Epistemic foundationalism, on the one hand, holds that many beliefs are justified by further beliefs, which may be justified by still further beliefs, etc., but that this chain of beliefs comes to an end in so-called basic beliefs: beliefs that do not rely on further beliefs for their justification (Quinton 1973, p. 119; Audi 1978, p. 49; Ginet 2005, pp. 141–143).Footnote 1 Dialectical foundationalism, on the other hand, holds that when S is challenged to justify her belief, and is asked for new reasons whenever she has given one, she does not have to go on giving reasons indefinitely. Rather, S does not have to cite a further reason when at some point she has asserted something that counts as dialectically foundational (Brandom 1994, chs. 3 and 4; Norman 1997; Leite 2005).

Given the distinction between epistemic and dialectical foundationalism, a first question that arises is which kind of foundationalism Klein is actually objecting to. Although Klein himself does not explicitly distinguish epistemic and dialectical foundationalism, it appears as if it is especially dialectical foundationalism that he has in mind. Often he speaks of foundationalism as accepting arbitrary assertions (e.g., Klein 1999, p. 303). In most of his papers, Klein also presents his case by considering a dialectical situation where he envisions

a type of socratic questioning that lies behind the regress of reason-giving that begins with the assertion of some proposition, say p, followed by the question, “Why do you believe that p?” The regress continues: Because I believe that q. “And why do you believe that q?” Because I believe that r. “And why do you believe that r?” Etc. (Klein 2004, p. 168).

Klein calls such imagined conversations “assertion/question dialogues” (168), “reason-giving games” (169), or “why-games” (171). It is in the context of such dialogs where someone is asked to justify her belief that foundationalism is said to involve arbitrariness: “even the practicing, self-conscious, modest foundationalist would fall into an unacceptable kind of arbitrariness once the regress of providing reasons begins” (168).

In order to see how Klein thinks this unacceptable arbitrariness is effected, it is useful to consider his description of the way a foundationalist supposedly must respond when he is asked to give reasons:

Now, imagine a dialog (even if it is a sotto voce one). Call the personae, Fred the Foundationalist and Sally the Skeptic. Fred begins by asserting something, say p, and Sally asks Fred why he believes that p. Fred gives his reason, say r. This goes on for a while, but eventually Fred gives what he takes to be a basic reason, say b. Sally asks Fred for his reason for b. Fred, being a foundationalist, says that there is no reason available for b—or more cautiously—there need be no reason available for b because b is propositionally justified at least to some degree but not in virtue of there being a reason for it (Klein 2007, p. 14).

Since foundationalists allow Fred to reason thus, they allow a “form of unacceptable arbitrariness in [his] reasoning” (Klein 2004, p. 167) or a vicious kind of “arbitrariness at the base” (Klein 1999, p. 297).

Given Klein’s repeated emphasis on dialectical situations, his main focus seems to be dialectical foundationalism. However, there are also indications that his target is epistemic foundationalism. First, Klein always presents foundationalism as opposed to epistemic views such as (linear and holistic) coherentism and infinitism. Second, at certain places, Klein mentions beliefs as the items constituting justificatory chains (e.g., Klein 1999, p. 299). Third, at some point, Klein explicitly describes foundationalism in an epistemic fashion (Klein 2000, p. 23). For this reason, and also because most foundationalists commenting on Klein treat his objection as an objection to epistemic foundationalism, I evaluate the objection both as directed at dialectical foundationalism and as directed at epistemic foundationalism.

3 Epistemic Arbitrariness

In order to be able to evaluate Klein’s objection, it is crucial to establish (1) what (kinds of) items are allegedly allowed to be arbitrary and (2) what, if those items are supposedly allowed to be arbitrary, is meant by “arbitrary.” As to the first question, Klein is not very clear.Footnote 2 However, since he is talking about either dialectical foundationalism or epistemic foundationalism, it is reasonable to assume that he thinks either assertions or beliefs are allowed to be arbitrary. Dialectical foundationalism holds that chains of justifying assertions terminate with foundational assertions; epistemic foundationalism has it that chains of justified beliefs come to an end in basic beliefs. According to Klein, in this way, foundationalist views advocate “arbitrariness at the base” (Klein 1999, p. 297). Given his mention of arbitrariness at the base, and given what dialectical and epistemic foundationalism posit at the base, I assume that it is either foundational assertions or basic beliefs that are supposedly allowed to be arbitrary. Turning to the second question, then, what does Klein mean when he calls assertions or beliefs “arbitrary”? I first discuss arbitrary assertions and then construe an analogous notion of arbitrary beliefs.

Items most naturally called arbitrary are choices. If one is asked to choose between two identical boxes, one of them containing $1000, the other being empty, without knowing which one contains the money, one chooses without having a reason. Since, judged from one’s perspective, nothing favors a particular choice, the choice one in fact makes may be considered arbitrary.Footnote 3

Although assertions may be rather different from choices, they resemble them in being evaluated in terms of reasons. Just as it is possible to ask for and give reasons for choices, is it possible to ask for and give reasons for assertions. Thus, it is natural to suggest that assertions are arbitrary if they are not supported by a reason. However, there are many different kinds of reasons for assertions. One can have moral reasons, and also pragmatic or political reasons. Yet, it is not the absence of such reasons that gives rise to the arbitrariness objection. Rather, it is the absence of epistemic reasons: foundationalism fails because it allows foundational assertions not supported by reasons for thinking they are true.

In order to explicate Klein’s notion of epistemic arbitrariness, it is useful to start by considering his “Principle of Avoiding Arbitrariness”:

For all x, if a person, S, has a justification for x, then there is some reason, r1, available to S for x; and there is some reason, r2, available to S for r1; etc. (Klein 1999, p. 299).

According to Klein, this principle entails that “the chain of reasons cannot end with an arbitrary reason—one for which there is no further reason” (Klein 1999, p. 299). So if an assertion is not to be arbitrary, there has to be a reason available for it. However, Klein argues, there just being a reason available does not suffice, for it appears that for any assertion there is a reason available. Suppose I assert that all fish wear army boots. Surely, when asked for a reason, I could say that all fish have fins and anything having fins wears army boots. Yet it is clear that the availability of this “reason” hardly suffices for my assertion not being arbitrary (Klein 1999, p. 300).

In order to rule out the possibility of such ad hoc reasons, Klein introduces the requirement that a reason be objectively available. By this, he means that a reason, r, must satisfy certain quality requirements, thus allowing r to be anchored in non-normative properties. For instance, r could be regarded objectively available as a reason for an assertion that p (1) if r has some sufficiently high probability and the conditional probability of p given r is sufficiently high; or (2) if an impartial, informed observer would accept r as a reason for p; or (3) if r would be accepted in the long run by an appropriately defined set of people. Klein lists seven possible accounts of objective availability and adds that it may be that another, yet unmentioned, account will turn out to be the best one (Klein 1999, p. 300). For the sake of discussion, I shall employ a concept of objective availability to the effect that r is an objectively available reason for an assertion A if and only if the probability of A, given r, is very high.

While a reason’s being objectively available is necessary for an assertion not to be arbitrary, in Klein’s view it is not sufficient. For if it were sufficient, then any assertion for which there is an objectively available reason would not be arbitrary, even if judged from the perspective of the person making the assertion it is merely an unfounded guess or hunch. Thus, Klein argues, a reason should also be subjectively available. By this, he means that it must be “properly hooked up” with beliefs she already holds; it must be a reason that she would endorse at least “in some appropriately restricted circumstances” (Klein 1999, p. 300). In Klein’s view, not only consciously believed reasons, such as the “reason” that 2 + 2 = 4, can be subjectively available. Also the “reason” that apples do not normally grow on pear trees and the “reason” that 366 + 71 = 437 can be subjectively available, even though one has never consciously entertained these “reasons” and although being able to endorse them may require a bit of adding (Klein 1999, p. 308).

So if an assertion is to avoid arbitrariness, it is necessary that it has a reason that is both objectively and subjectively available. Given that Klein does not mention further criteria, it is safe to assume that he also regards this sufficient for avoiding arbitrariness. Since an assertion avoids being arbitrary if and only if it has a reason that is objectively and subjectively available, an assertion is arbitrary if and only if it lacks an objectively and subjectively available reason. (Henceforth, I use “objective” for “objectively available,” “subjective” for “subjectively available,” and “objective and subjective reason” for “reason that is both objectively and subjectively available.”)

Since an assertion A is arbitrary if it lacks a reason that is both objective and subjective, it can be arbitrary in more than one way. A can be arbitrary in virtue of lacking both an objective and a subjective reason; A can be arbitrary in virtue of lacking only an objective reason; and A can be arbitrary in virtue of lacking only a subjective reason. Because of these different ways in which an assertion’s arbitrariness can be realized, it is possible to isolate different forms of arbitrariness. For the purposes of this paper, I mention two forms. When an assertion lacks an objective reason, I call the assertion objectively arbitrary. When an assertion has an objective reason that is not subjective, I call the assertion subjectively arbitrary.

Given this analysis of arbitrary assertions, it is rather easy to develop an analogous notion of arbitrary beliefs. Since also beliefs are evaluated in terms of reasons, it can be said that a belief is arbitrary if and only if it has no objective and subjective reason. I assume that r is an objective reason for a belief B if and only if the probability of B, given r, is very high. Because a belief’s lacking an objective and subjective reason can be realized in more than one way, I also isolate two senses in which a belief can be arbitrary. When a belief has no objective reason, I call it objectively arbitrary; when a belief has an objective reason that is not subjective, I call it subjectively arbitrary.Footnote 4

In the sections that follow, I shall evaluate Klein’s objection. In Section 4, I consider whether dialectical foundationalism has to allow arbitrary assertions; in Section 5, I consider whether epistemic foundationalism must countenance arbitrary beliefs.

4 Dialectical Foundationalism and Arbitrariness

Does dialectical foundationalism have to sanction arbitrary assertions? Recall how Klein represents “Fred the Foundationalist” as arguing when he is asked to give a reason for the allegedly foundational assertion that b:

Fred, being a foundationalist, says that there is no reason available for b—or more cautiously—there need be no reason available for b because b is propositionally justified at least to some degree but not in virtue of there being a reason for it (Klein 2007, p. 14).

If it is true (what Fred says) that there is no reason available for b, and hence neither a reason that is both objective and subjective, then the assertion that b is arbitrary. So if dialectical foundationalists argue in the way Fred argues, they do indeed allow arbitrariness. However, must dialectical foundationalists necessarily argue as Fred does? Dialectical foundationalism holds that when S is challenged to justify her belief, and is asked for new reasons whenever she has given one, she does not have to go on giving reasons indefinitely. Rather, S does not have to cite a further reason when she has asserted something that counts as dialectically foundational. Does this view necessarily allow foundational assertions that lack an objective and subjective reason?

Presumably, this depends on how dialectical foundationalism should think of foundational assertions. There exist versions of the position that construe foundational assertions such that they can terminate dialectical regresses even when they lack an objective and subjective reason (e.g., Brandom 1994, Ch. 3, and Norman 1997). However, it is by no means clear that foundationalism is committed to such a view of foundational assertions. Nothing in the concept of dialectical foundationalism prevents it from construing foundational assertions as assertions that must have an objective and subjective reason. In fact, some dialectical foundationalists do explicitly regard them in that way. According to Adam Leite, for instance, if someone is asked to give a reason for what she has asserted, and after she has given a reason is asked for a further reason, etc.,

[a]t a certain point (…) a request for further reasons is inappropriate, and the defendant’s pointing this out may legitimately terminate the justifying episode (Leite 2005, p. 403).

However, Leite stresses, in this way terminating a justificatory regress is possible only “so long as the defendant possesses reasons in favour of the belief at issue” (403). That Leite regards the availability of reasons, even for foundational assertions, pivotal becomes manifest also in what he considers to be “the norm governing justificatory conversations”:

Don’t request further reasons if the defendant correctly and responsibly takes there to be no reason for doubt; under such conditions the defendant need not provide justifying reasons (though she must believe things which constitute such reasons) (407, my italics).

Again, considering someone making an assertion for which she has no reason, but who nevertheless dismisses a request for reasons, Leite says that her response “would be sheer dogmatism” (405). As Leite’s remarks illustrate, nothing prevents dialectical foundationalism from construing foundational assertions such that they must have an objective and subjective reason. Hence, dialectical foundationalism has a way to avoid arbitrary assertions. But if this is so, Klein’s argument construed as targeting dialectical foundationalism does not succeed.

5 Epistemic Foundationalism and Arbitrariness

How about Klein’s objection regarded as an objection to epistemic foundationalism? According to epistemic foundationalism, justificatory chains of beliefs come to an end in “basic beliefs”: beliefs that are justified without relying for their justification on further beliefs. Klein’s objection is that in allowing basic beliefs to terminate epistemic regresses, foundationalism licenses arbitrary beliefs. Since several foundationalists have already responded to Klein’s objection so construed, I begin with evaluating their arguments in Section 5.1. I discuss the responses advanced by Michael Huemer, Michael Bergmann, and Daniel Howard-Snyder and E.J. Coffman. After arguing that their arguments are less convincing than they are presented as being, I give my own assessment of the arbitrariness objection in Sections 5.2 and 5.3.

5.1 Three Foundationalist Responses

According to Michael Huemer, on most interpretations, Klein’s objection is not so much an objection to foundationalism, as a question-begging rejection of it. To argue that foundationalism is unacceptable because it involves epistemic arbitrariness, says Huemer, “is simply to repeat the thesis of foundationalism, appending the assertion that the thesis is unacceptable” (Huemer 2003, p. 143). That Huemer is able to so respond to the objection is due to his definition of foundationalism:

The central idea of foundationalism is that in some circumstances, we do not need reasons for believing a proposition to be justified in believing it. More precisely: (…) For some persons S and some propositions P, S is justified in believing P, and some of S’s justification for believing P does not depend upon S’s having a reason or reasons for believing P (Huemer 2003, p. 141; cf. Huemer 2010, p. 22).

Huemer defines basic beliefs as beliefs for which no reasons are needed. Since arbitrary beliefs are beliefs that have no (objective and subjective) reason, this means that he defines basic beliefs as beliefs that are allowed to be arbitrary. Hence, if foundationalism is construed as Huemer construes it, then the objection that it fails because it allows arbitrariness is indeed viciously circular. What is expected of an objection to foundationalism is more than a mere assertion that it is unacceptable.

I think Huemer’s response to Klein’s objection is unconvincing for two reasons. First, even if the arbitrariness objection, as an objection to foundationalism as defined by Huemer, begs the question, one may still wonder whether Huemer need not account for the fact that his version of foundationalism allows arbitrary beliefs. If someone were to define foundationalism so that basic beliefs are beliefs that stand in need only of bad reasons, then to object that this foundationalist view allows basic beliefs for which there are only bad reasons would certainly beg the question. Yet it seems that someone defending such a view may be expected at least to explain why allowing such basic beliefs is unobjectionable.

Second, most foundationalists define foundationalism in a way different from the way Huemer defines it. Instead of saying that basic beliefs do not stand in need of reasons, they construe basic beliefs as beliefs that do not rely on further beliefs. When basic beliefs are construed in that way, foundationalism does not involve epistemic arbitrariness in the direct way that Huemer’s account does. Hence, to claim that foundationalism allows arbitrariness need not be question-begging.

Michael Bergmann’s response targets Klein’s concept of arbitrariness. Klein holds that a belief is arbitrary if and only if it has no objective and subjective reason. Bergmann rejects this notion. He argues that a foundationalist confronted with Klein’s objection should be advised to respond as follows:

I say a belief for which one has no reason can avoid being arbitrary if it has some feature F such that beliefs having feature F are noninferentially justified (Bergmann 2004, p. 164).

Thus, Bergmann advices a foundationalist to cite the presence of a “meta-justification.” However, when he is in fact “drawing attention to the meta-justificatory argument, the foundationalist is not offering a reason for his basic beliefs” (164). Rather,

the foundationalist is using the ideas in that meta-justificatory argument to explain why it is that lacking a reason for a belief is not sufficient for that belief’s being arbitrary. The aim is to avoid the appearance of arbitrariness, not by providing a reason for [the basic belief] b, but by casting doubt on an assumption about what is sufficient for b’s being arbitrary (164–165).

What to think of this appeal to meta-justifications? I first note that it appears hard to make sense of Bergmann’s claim that drawing attention to the meta-justificatory argument does not involve giving a reason. Consider an allegedly basic belief B. Let’s say that B has the feature, F, of being reliably produced by a properly functioning perceptual system. Assume that Bergmann says that in such a situation, B has a meta-justification. How can appealing to this meta-justification not involve adducing a reason? Recall that r is an objective reason for B if and only if the probability of B, given r, is very high. Since justification is supposed to be truth-conducive, the fact that B’s having F provides B with a meta-justification presumably indicates that it makes B very likely to be true. So the fact that B has F forms an objective reason for B. But if that is so, then certainly asserting that B has F is to give a reason for B.

Setting this worry aside, though, does Bergmann succeed in showing how the presence of meta-justifications precludes arbitrariness? Recall that avoiding arbitrariness requires a reason that is both objective and subjective. A belief is objectively arbitrary if it has no objective reason, and subjectively arbitrary if it has an objective reason that is not subjective. Given what I said in the previous paragraph, it is clear that the presence of a meta-justification involves the existence of an objective reason. If B’s having F provides B with a meta-justification, then it makes B very likely to be true. Hence, B’s having a meta-justification does prevent B from being objectively arbitrary.

How about subjective arbitrariness, though? In order to avoid also this form of arbitrariness, the fact that B has an objective reason does not suffice. The person holding B should also have a certain degree of access to that reason. Suppose that S holds B and that B is produced by S’s reliably functioning visual system. Bergmann says that the existence of this meta-justification ensures that B is not arbitrary. However, suppose that S himself has no idea whatsoever about B’s origin. When asked why he holds B, S does not know anything to cite in support of his belief. Seen from his perspective, B has just popped into his head from nowhere; to him, B appears to be a mere guess or hunch. In such a case, it is obvious that B is subjectively arbitrary. Hence, Bergmann’s appeal to meta-justifications fails to do what he claims it does. Though the presence of such justifications may rule out objective arbitrariness, it does not preclude subjective arbitrariness.

As it stands, the claim that meta-justifications rule out arbitrariness is false. However, could Bergmann’s remarks not be interpreted differently? Perhaps his only concern is to show that meta-justifications rule out objective arbitrariness. Though beliefs that are not objectively arbitrary could still be subjectively arbitrary, Bergmann could be taken to hold that this latter kind of arbitrariness is not objectionable.Footnote 5 On this interpretation, Bergmann would take a typically externalist line of argument, saying that although S has no idea where some purported basic belief B comes from, although S does not have any clue what to say when B is challenged, and although from his point of view B seems a mere hunch, B may nevertheless be justified, as long as B has a suitable meta-justification. In countenancing B as being justified, Bergmann would simply bite the bullet that his verdict involves subjective arbitrariness. Or he would even be proud that his epistemology allows such beliefs to be justified, since it also allows children, lower animals, and supermarket doors to have justified beliefs, and since (he thinks) an epistemic theory should allow for that.

Would Bergmann’s argument, so construed, succeed in dismantling Klein’s objection? Obviously, internalists such as Klein deny that a belief can be justified when it is subjectively arbitrary. They find pressing intuitions telling against beliefs where the person holding them has no clue whatsoever why they would be true, and where the beliefs just appear to pop into her head from nowhere. Though it may be valuable that S’s belief has a meta-justification, it is also required that S has access to (what is responsible for) that justification. Thus, Klein and other internalists would not be persuaded by Bergmann’s externalist proposal that the presence of a meta-justification suffices for avoiding arbitrariness and for guaranteeing justification.

This controversy between externalists and internalists is very old, and it seems that a solution to it is not to be expected soon. In Alston’s (2005) terms, internalists and externalists press different epistemic desiderata. Both agree that (i) there being an objective reason and (ii) this reason also being subjective are valuable from an epistemic point of view. But when a particular belief has an objective reason that is not subjective, whether one is willing to regard the belief as justified depends on which of these two desiderata one considers decisive. Externalists press the desideratum that there must be an objective reason, whereas internalists emphasize that this reason must also be subjective. As long as internalists and externalists keep appealing to their intuitions, it is very unlikely that this debate is going to be settled. Since internalists cite intuitions not shared by externalists and vice versa, there appears to be no neutral way of bringing the dispute to an end (Alston 2005, pp. 53–57).

If Bergmann’s approach were the externalist approach sketched above, he and Klein would get involved in such a standoff. Whereas Klein would have intuitions telling him that a subjectively arbitrary belief cannot be justified, Bergmann would not have these intuitions or would ignore them in favor of others. And since Bergmann would not share Klein’s view on the normative status of subjective arbitrariness, in a sense his position would be immune to Klein’s objection. After all, that objection presupposes that subjective arbitrariness is objectionable, something Bergmann denies. At the same time, however, it would be improper to describe Bergmann’s response as an argument establishing that Klein’s objection fails. For just as Klein’s objection presupposes something Bergmann does not accept, Bergmann’s response relies on a premise Klein does not accept. Rather, what Bergmann’s response would boil down to is a venting of intuitions about arbitrariness that are different from those enjoyed by internalists. And although Bergmann’s view so construed would be immune to Klein’s objection, it is clear that his response could not reasonably be expected to convince Klein. While Klein’s objection, relying on internalist intuitions about subjective arbitrariness, would not persuade Bergmann, Bergmann’s response, relying on his externalist intuitions, would definitely not persuade Klein.

I draw two conclusions. First, Bergmann does not succeed in showing what he says he shows, i.e., how the presence of a meta-justification rules out arbitrariness. A belief having such a justification can still be subjectively arbitrary. Second, if Bergmann’s argument is reinterpreted as saying that the presence of a meta-justification rules out objective arbitrariness and that other forms of arbitrariness are unobjectionable, it turns out that Klein’s objection need not be fatal to his view. Yet, in that case, Bergmann’s arguments cannot properly be said to show that the objection fails, and his argument will not even begin to convince Klein.Footnote 6

Still another response to Klein’s objection has been adduced by Daniel Howard-Snyder and E.J. Coffman. Of the five possible interpretations of Klein’s objection they suggest, the following reconstruction seems to come closest to what Klein is in fact arguing:

If Foundationalism is true, then there could be basic beliefs of the following kind: S’s basic belief that p is justified although there are no further beliefs of S that make it even slightly better that S believe p rather than any of p’s contraries. Since Foundationalism implies that there could be basic beliefs of this kind, and there couldn’t be, Foundationalism is false (Howard-Snyder and Coffman 2006, p. 541).

According to Howard-Snyder and Coffman, neither internalist nor externalist foundationalists need be impressed by this objection. Consider how they think internalists can escape the charge of arbitrariness:

if you are an internalist, and, more importantly, if your particular brand of internalism implies that one’s belief that p is justified only if one has some further beliefs that support p over its contraries, you can still be a foundationalist (…) provided that you allow that in some cases, namely the case of basic beliefs, one’s belief does not owe its justification to those further beliefs (541).

“Of course,” Howard-Snyder and Coffman admit, a proponent of such an internalist foundationalism “will need to explain why one must have those further beliefs in the first place” (541). However, it seems that she has to explain more than just that. First, in describing the internalist option the way they do, Howard-Snyder and Coffman assume that it is possible that S’s belief is justified only if she has further beliefs that support it over its contraries, while at the same time it does not owe its justification to those further beliefs. So the presence of supporting beliefs is posed as a necessary condition for another belief’s justification, while the latter belief is said not to owe its justification to those supporting beliefs. Yet it seems very hard to make sense of the idea that some condition is a necessary condition for a belief’s justification while at the same time the justified belief does not owe its justification to the satisfaction of that condition. Second, and relatedly, it is doubtful whether the internalist view described by Howard-Snyder and Coffman can still be called foundationalist. If someone’s basic belief can be justified only if she has other beliefs that support it over its contraries, certainly it is not the case that that belief does not rely on other beliefs for its justification.Footnote 7 Thus, foundationalism of this internalist variety cannot escape the charge of arbitrariness in the way Howard-Snyder and Coffman think it can.

Howard-Snyder and Coffman also hold that externalist versions of foundationalism do not have to worry about the arbitrariness objection. When externalists maintain that S’s belief B can be justified even if S has no access to reasons for B, Klein objects that their view allows subjective arbitrariness. Although certain external factors may prevent B from being objectively arbitrary, B is subjectively arbitrary as long as S has no clue as to why B would be true. Howard-Snyder and Coffman find Klein’s objection unconvincing:

Externalists tend to allow for cases in which one’s belief that p is justified even if one has no further beliefs that support p over its contraries (…). So if you are an externalist, you will probably not be much impressed by the premise above that there could not be a case of the sort in question [i.e., a case of someone having a basic belief not supported by further beliefs] (541).

However, why exactly is it that externalists need “not be much impressed” by Klein’s objection? Given that their position is said to allow arbitrariness, one would at least expect some response. Presumably, Howard-Snyder and Coffman could follow the same strategies as Bergmann. One option would be to assert that externalist foundationalism does not allow arbitrariness at all. However, as Howard-Snyder and Coffman’s argument stands, it does not begin to make that claim plausible. Externalist foundationalism can avoid objective arbitrariness by requiring the presence of an objective reason. But as long as it allows S’s belief to be justified in cases where an objective reason is not subjective to S, it clearly countenances subjective arbitrariness.

A second possibility is that Howard-Snyder and Coffman assert that it suffices if externalism rules out objective arbitrariness. Perhaps externalism licenses justified beliefs that are subjectively arbitrary, but the arbitrariness enjoyed by such beliefs is not vicious.Footnote 8 As with Bergmann, taking this line would render their position immune to Klein’s objection. But at the same time it is unreasonable to expect that this response would even begin to convince Klein. Externalists may discover strong intuitions to the effect that some subjectively arbitrary beliefs are justified, but Klein does not share those intuitions. Hence, this line of defense would not so much count as an attempt to show that Klein’s objection fails but rather as an expression of different intuitions about arbitrariness.

5.2 Objective Reasons for Basic Beliefs

The responses proffered by Huemer, Bergmann, and Howard-Snyder and Coffman cannot be expected to convince Klein. In the current section, I shall attempt to really establish that Klein’s argument fails.

Given the concept of arbitrariness assumed in this paper, the crucial question with regard to Klein’s objection is whether foundationalism must allow beliefs that lack an objective and subjective reason. Presumably, the only ground for thinking they must allow such beliefs is that requiring that beliefs have an objective and subjective reason involves the justificatory presence of further beliefs. For if it involves this, then foundationalists, in their attempt to avoid arbitrariness, have to regard basic beliefs as requiring further beliefs. So the decisive question is whether a belief’s having an objective and subjective reason involves the presence of a further belief. In the present section, I discuss what is implied by having an objective reason; in Section 5.3, I consider what is involved by having a subjective reason.

Whether a belief’s having an objective reason involves a further belief depends on what kinds of items can be objective reasons. If only beliefs can be objective reasons, then a belief’s having such a reason obviously involves the presence of a further belief. But regardless of whether beliefs can be objective reasons at all, the suggestion that only beliefs can be objective reasons is wildly implausible. Consider the natural law saying that iron expands when heated. At some time in the past, t, this law was not yet believed to obtain. Suppose that at t some piece of iron was in fact heated. If only beliefs can be reasons, and if at t no other relevant beliefs about iron and heating were held, then at t there was no reason at all for believing that the piece of iron would expand. But this consequence is highly counterintuitive. We don’t say that there was no objective reason for believing that the piece of iron would expand, but that the reason that obtained was not yet believed to obtain; that although the reason existed, it had still to be discovered.Footnote 9

So presumably, other items can be objective reasons as well. For the purposes of this paper, I shall especially focus on two plausible candidates: facts and experiences. Many epistemologists have noticed that ordinary language suggests that reasons could be facts (Pollock 1974, p. 25; Alston 1988, p. 230; Millar 1991, p. 65; Thomson 2008, p. 128). For instance, in the example given above, at t an objective reason for believing that the piece of iron would expand was the fact that iron expands when heated. Similarly, a reason for believing that the train shall leave at 12:33 is the fact that the schedule says that it leaves at 12:33. These facts form objective reasons for the corresponding beliefs because the likelihood of the beliefs, given the facts, is very high. Analogously, many philosophers maintain that particular sensations or perceptual experiences can be reasons (Pryor 2000; Alston 2002, pp. 81–85; Turri 2009; Rescorla 2009, pp. 50–54). For instance, when a visual experience as of a maple tree outside prompts me to believe that there is a maple tree outside, my experience is a good reason for holding that belief. Likewise, if an auditory experience as of a bus approaching from behind causes me to believe that a bus is approaching, my experience forms a perfect reason for the belief. These experiences constitute objective reasons for the beliefs they engender, since given the experiences, the beliefs are highly likely to be true.

I assume that these examples illustrate that both facts and experiences can be objective reasons for beliefs. Many facts are such that given that they obtain, a corresponding belief is highly probable, and very often, a subject’s having a particular experience makes it extremely likely that a corresponding belief is true. Regardless of whether any person has these facts or experiences subjectively available, they can at least be objective reasons. But if that is true, it is safe to assert that a belief’s having an objective reason need not involve the justificatory presence of a further belief. So nothing prevents foundationalism from requiring basic beliefs to have an objective reason.

5.3 Subjective Reasons for Basic Beliefs

How about subjective reasons, though? Can an objective reason be required to be also subjective without this involving the presence of a further belief? Footnote 10 This of course depends on what “being subjective” means. In Section 3, we saw that on Klein’s account reasons can be subjective even if they are not consciously believed. Also reasons that one has never entertained, e.g., the “reason” that apples do not normally grow on pear trees, and even reasons that one can endorse only after some adding, e.g., the “reason” that 366 + 71 = 437, can be subjective. Such reasons are subjective if they are “correctly hooked up to already formed beliefs” (Klein 1999, p. 308). Elsewhere, Klein argues that reasons can be subjective (or available “in the appropriate sense”) even if what is needed in order to believe them is “new experiences, insight and perhaps a certain amount of luck” (Klein 2000, p. 23). For instance, though at some point in history we did not yet believe that many diseases are caused by microscopic organisms, we did have the capacity to form this belief. Hence, Klein says, also this “reason” has always been subjective (23). In a later paper, Klein suggests that a reason that p is subjective to S “just in case there is an epistemically credible way of S’s coming to believe that p given S’s current epistemic practices” (Klein 2007, p. 13). Reasons that are subjective to S “are like money in S’s bank account that is available to S if S has some legal way of withdrawing it even if S is unaware that the money is there or takes no steps to withdraw it” (13). Suppose S is asked what is the capital of Montana. If her epistemic practices are such that for this she has to check the state capital listings in the World Almanac, then the fact that this almanac lists Helena as the capital of Montana entails that the “reason” that Helena is the capital of Montana is subjective to S (13).

Given these examples, it is safe to say that a reason’s being subjective need not involve the presence of (further) beliefs. So on Klein’s concept of subjective reasons, it is clearly open to foundationalism to construe basic beliefs so that they must have an objective reason that is also subjective. Hence, on Klein’s assumptions, it is possible for foundationalism to rule out arbitrary basic beliefs. But if this is possible, then Klein’s claim that foundationalism allows arbitrary basic beliefs is false. If we accept Klein’s concept of objective and subjective reasons, his objection to foundationalism does not succeed.

However, it may be wondered whether this conclusion is not reached a bit easily. That foundationalism can require objective reasons to be also subjective is due to a rather lenient conception of subjective reasons. But is this conception not much too lenient? Klein assumes that any capacity to discover an objective reason suffices for S’s belief for which it is a reason not to be arbitrary, even if as yet S has no idea why his belief would be true. However, does not this assumption judge not arbitrary many beliefs that are clearly arbitrary?Footnote 11 Suppose S holds the belief, B, that Jones is having a party. Since there are a lot of cars around Jones’s house, and since this makes it very likely that B is true, B has an objective reason. Moreover, assume that S is in a position where she can travel to Jones’s house in order to see the cars standing around the house. Since S has this capacity, the objective reason is also subjective to S. Hence, on Klein’s account, B is not arbitrary. However, if we suppose that at the moment S has no clue whatsoever as to why B would be true, Klein’s verdict appears to be false. As long as S has no idea about the existence of a reason, her belief still seems subjectively arbitrary in an important sense. Analogously, suppose I believe that Helena is the capital of Montana. Since I can check with the World Almanac to find out that this is true, Klein judges that my belief is not arbitrary. However, suppose that before in fact consulting the almanac I have no idea whatsoever about the truth of my belief; that judged from my point of view it is nothing but a mere guess. Klein’s judgment here does not seem to be correct. My belief is subjectively arbitrary.

What this shows, I think, is that Klein’s requirement for subjective availability is far too weak.Footnote 12 In order for a reason r to be appropriately subjective to S, it does not suffice that S has some capacity to discover r, or that S’s epistemic practices provide her with a credible way of detecting r. A reason’s being sufficiently subjective requires the satisfaction of a stronger requirement. That requirement should not only render subjective all reasons that clearly are sufficiently available but should also judge not subjective all reasons that Klein’s concept wrongly judges to be sufficiently available.Footnote 13 However, if such a stronger requirement is to be of any use to the foundationalist concerns of this paper, it should at the same time be weak enough to not involve the presence of beliefs. Hence, the pivotal question becomes whether foundationalism can find a requirement that is both strong enough to rule out the reasons Klein wrongly regards subjective, and weak enough to not involve beliefs.

In order to show how I think foundationalism can find such a requirement, I draw attention to an availability requirement proposed by Alston (1988). Alston holds that a belief not only needs to have an objective (or, in his terms, adequate) reason but that this reason should also be “fairly readily available to the subject through some mode of access much quicker than lengthy research, observation, or experimentation” (238). A reason should be “the sort of thing that, in general, a subject can explicitly note the presence of just by sufficient reflection on his situation” (238). Drawing on this suggestion, I say that a reason r is strongly subjective to S if and only if S can note the presence of r just by reflecting on her present situation. A strong availability requirement holds that S’s belief B avoids being arbitrary only if an objective reason for B is strongly subjective to S.

Can this strong availability requirement satisfy the aims of foundationalism? I first consider whether it is strong enough, then whether it is weak enough. The requirement is strong enough if it not only judges subjective all reasons that clearly are sufficiently available but also judges not subjective all reasons that Klein’s concept wrongly judges to be sufficiently available. Presumably, the requirement does give the right verdict about many clearly subjective reasons. Suppose my experience as of a grey coffee cup prompts me to believe that there is a grey coffee cup placed on my desk. Once I start to wonder why I hold the belief, I recognize my experience as a reason. So this reason is clearly subjective. Since I can note its presence by reflecting on my present situation, it also satisfies the strong availability requirement. Or imagine that I believe my fiancée is home after she told me this morning that she would be working home today. When I start to think about it, I remember what she told me this morning and cite that as a reason for my belief. Clearly, the fact about what she told me is a subjective reason. And since I can note it just by reflecting on my present situation, also the strong availability requirement judges it subjective. Thus, the strong availability requirement renders subjective such readily available reasons.

More importantly, however, does it also judge not subjective all reasons that Klein’s concept wrongly judges to be sufficiently subjective? Recall S’s belief that Jones is having a party, where S can come to discover that there are a lot of cars around Jones’s house. On Klein’s concept, the objective reason for this belief is also subjective. However, on the strong availability requirement, this reason turns out to be not subjective. If S first has to travel to Jones’s house in order to detect the objective reason, she is not in a position where she can note the presence of that reason just by reflecting on her present situation. Similarly, Klein judges that the objective reason for my belief that Helena is the capital of Montana is sufficiently subjective, since I can always check the Almanac. Yet the strong availability requirement renders this reason not subjective: I cannot find the Almanac’s contents just by reflecting on my situation. Thus, the strong availability requirement is sufficiently strong: not only does it judge subjective those reasons that clearly are readily available, it also renders not subjective reasons that Klein’s weak requirement wrongly judges subjective.

Is the strong availability requirement also weak enough, though? It is weak enough if it does not involve the presence of further beliefs. According to the requirement, S should be able to explicitly note the presence of an objective reason just by sufficient reflection on his situation. But to require this is not yet to require the presence of a further belief. As S has to be able to note the presence of the reason by reflection on his situation, that reason clearly has to be part of his situation already: it does not suffice that S can discover the reason by traveling to a distant place or by consulting an almanac. But from that it does not follow that the reason has to be believed already. There are many things which are part of my present situation that I do not yet believe. Currently, an enormous amount of biological and neurophysiological processes are operative in my body. But though they are part of my present situation, I do not hold any beliefs about those processes.

Similarly, again consider the case where a visual experience as of a grey cup on my desk prompts me to believe that there is a grey cup on my desk. Though that experience is part of my present situation, as yet I hold no beliefs about it. Or suppose that the fact that leaves are falling causes me to believe that autumn has begun. The fact regarding the leaves clearly affects my present situation. Yet it is possible that as yet I have not formed any beliefs about it. To be sure, when I were to reflect on my situation, e.g., by asking why I believe that the cup is on my desk or that autumn has begun, I would presumably come to believe things about my experience and facts regarding the leaves. But before reflecting on these matters, I did not have any beliefs about them. Rather, that I come to believe things about my experience and the leaves upon reflection presupposes that I did not believe those things before. Thus, the envisaged requirement is also weak enough: it is possible for a reason to meet it without this involving a further belief.

The strong availability requirement is both strong enough and weak enough. So, unlike Klein’s requirement, this requirement can really be used to ensure that reasons are sufficiently subjective vis-à-vis the aim of avoiding arbitrariness. Hence, foundationalism can require basic beliefs to have a reason that is both objective and sufficiently subjective. Therefore, it can rule out arbitrary beliefs not only on Klein’s lenient view of subjective reasons but also on a concept that involves a much stronger availability requirement.

Let me draw the threads of this long section together. First, I showed that the arguments given by several foundationalists do not succeed in establishing that Klein is wrong. At best, their arguments can be reinterpreted as presenting a view that is immune to Klein’s objection. But, in that case, they cannot reasonably be expected to persuade Klein. Second, I attempted to really establish that Klein is wrong. I argued that since facts and experiences can be objective reasons, nothing prevents foundationalism from requiring basic beliefs to have an objective reason. I also argued that it can require that this objective reason is subjective. On Klein’s notion of subjective availability, this is rather easy. But I have shown that it is also possible to require that objective reasons are available in a stronger sense. When a strong availability requirement is posed, foundationalism ensures that an objective reason should also be sufficiently subjective. Since foundationalism can require basic beliefs to have a reason that is both objective and strongly subjective, it can avoid arbitrary basic beliefs. Hence, Klein’s objection to foundationalism is unsound.

6 Conclusion

In this paper, I have argued that Klein’s arbitrariness objection, regarded as an objection either to dialectical foundationalism or to epistemic foundationalism, fails. With regard to dialectical foundationalism, I argued that nothing prevents it from construing foundational assertions as having an objective and subjective reason. With regard to epistemic foundationalism, I argued that neither a belief’s having an objective reason nor its having a subjective reason need involve the presence of further beliefs. As a result, I argued, foundationalism can construe basic beliefs as having an objective and subjective reason.

Thus, I have argued that both versions of foundationalism can avoid arbitrariness by requiring that what they posit at the basis has an objective and subjective reason. However, a question remains: have I not merely replaced one problem for another? I may have shown that foundational assertions and basic beliefs need not be arbitrary, but what about the reasons for those assertions and beliefs? Are they not vulnerable to a similar arbitrariness objection? If there are no reasons for these reasons, are not these new items “at the base” arbitrary? After all, as we have seen, Klein sometimes phrases his objection by saying that “foundationalism is unacceptable because it advocates accepting an arbitrary reason at the base” (Klein 1999, p. 297, my italics).

Though this question is rather intuitive, there is a proper answer to it. In Section 5.2, I argued that epistemic foundationalism could think of objective reasons as being non-doxastic items such as perceptual experiences or facts. Analogously, dialectical foundationalism can think of reasons for foundational assertions as experiences or facts. But if foundationalism can construe those reasons as experiences or facts, it can easily respond to the worry that they are also arbitrary as long as they lack a further reason. In Section 3, I explained that items primarily called arbitrary are choices. Though assertions and beliefs are rather different from choices, they resemble them in being evaluated in terms of reasons. Therefore, they can be considered arbitrary too. However, experiences and facts are different not only from choices but also from assertions and beliefs. Assertions and beliefs can be true or false, but experiences and facts cannot; assertions and beliefs can be evaluated in terms of reasons, but experiences and facts cannot. And, crucially, as experiences and facts cannot be evaluated in terms of reasons, they cannot be epistemically arbitrary. So, since foundationalism can think of objective reasons as experiences or facts, it can avoid arbitrary foundational assertions and beliefs without positing other arbitrary items at the base.

My arguments in this paper are not meant as a final defense of foundationalism. There may be very good reasons for rejecting foundationalism after all. What I have shown, though, is that foundationalism can require foundational assertions and basic beliefs to have a reason that is both objective and strongly subjective. Assuming that having such a reason suffices for assertions and beliefs not to be arbitrary, one can be a foundationalist and not allow arbitrariness at the base.

Notes

Not all foundationalists construe basic beliefs in this way. Plantinga (1993, p. 68) thinks of them as beliefs that do not rely on other beliefs as evidence. Alston (1976a, p. 19) and Pryor (2000, p. 532) construe them as beliefs that are justified without relying on further justified beliefs for their justification. It will become clear in Section 4 that dismantling Klein’s objection to epistemic foundationalism is much easier if one of these latter concepts is assumed. Since the notion mentioned in the main text is the strongest, however, I prefer to employ that notion. If, as I shall argue, epistemic foundationalism can withstand Klein’s objection while assuming the strongest notion, it can also stand up to the objection while assuming one of the weaker notions.

Sometimes he speaks of arbitrary reasons (Klein 1999, pp. 297, 299, 303), sometimes of arbitrary beliefs (Klein 1999, pp. 299, 304), sometimes of arbitrary assertions (Klein 1999, p. 303), sometimes of arbitrary propositions (Klein 1999, p. 304; Klein 2000, p. 12), and sometimes of arbitrary suppositions (Klein 2000, p. 8). Elsewhere, he also speaks of treating a proposition as foundational (Klein 1998, p. 924), of stopping to give reasons (Klein 2000, p. 21), and of using b as a reason (Klein 2005, p. 134) as being arbitrary.

Throughout the present paper, I shall take Klein’s concept of arbitrariness for granted. For an evaluation of his concept, see Engelsma (2014).

I thank an anonymous referee for bringing this interpretation to my attention.

As I shall show in Sections 5.2 and 5.3, it is possible for foundationalists to give a much stronger response to Klein’s objection. That response defends a form of foundationalism which requires that basic beliefs have a reason that is both objective and subjective, and therefore attempts to show that Klein is wrong on terms that also he accepts.

That basic beliefs do not rely on further beliefs is a requirement that also Howard-Snyder and Coffman endorse (535).

In a different paper where he argues against Klein’s objection in a similar fashion, Howard-Snyder intimates that he does not feel attracted to this second option: “Unfortunately, the foundationalist cannot find solace in arbitrariness. That’s because justification just is being nonarbitrary in the relevant sense; (…) So the arbitrariness option reduces to the denial of Foundationalism” (Howard-Snyder 2005, p. 20).

Some think that Klein holds that only beliefs can be objective reasons (Ginet 2005, p. 143; Howard-Snyder 2005, p. 20). However, it is not clear exactly why they attribute this view to Klein. Though sometimes what he says seems to indicate that he regards especially beliefs as reasons, there are strong indications that he thinks of other items as reasons as well. First, consider his requirement that reasons be both objective and subjective. If only beliefs can be objective reasons, a reason can only be objective if it is a belief. But if a reason can only be objective if it is a belief, a reason can only be objective if it is also subjective. Yet, in that case, the requirement that reasons be not only objective but also subjective becomes unintelligible (or at least tautological). Second, at several places, Klein explicitly speaks of other items as reasons for beliefs. Sometimes, he speaks of reasons for beliefs as if they are particular facts (e.g., Klein 1998, p. 924); at other places, he mentions propositions as reasons for beliefs (e.g., Klein 2007, p. 12).

If basic beliefs are construed in one of the alternative ways mentioned in footnote 1, then showing that foundationalism can require that objective reasons for basic beliefs are also subjective becomes much easier. For in that case, foundationalism can require the presence of further beliefs, provided that those beliefs do not function as evidence or need not be justified. I keep focusing on the stronger notion, however, since I think it is possible to require the presence of objective and subjective reasons even on that notion.

I thank an anonymous referee for pressing this question.

I think Klein is tempted to let his notion of subjective availability be so weak because, as an infinitist, he wants to leave room for human beings having an infinite number of reasons available. Employing a stronger notion of subjective availability would tend to rule out this possibility.

The idea to distinguish between Klein’s weak availability requirement on the one hand and a (more appropriate) stronger requirement on the other was suggested to me by an anonymous referee.

References

Alston, W. (1976a). Two types of foundationalism. In W. Alston (Ed.) (1989), Epistemic justification. Essays in the theory of knowledge (pp. 19–38). Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Alston, W. (1976b). Has foundationalism been refuted? In W. Alston (Ed) (1989), Epistemic justification. Essays in the theory of knowledge (pp. 39–56). Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Alston, W. (1988). An internalist externalism. In W. Alston (Ed) (1989), Epistemic justification. Essays in the theory of knowledge (pp. 227–245). Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Alston, W. (2002). Sellars and the “Myth of the Given”. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 65(1), 69–86.

Alston, W. (2005). Beyond “Justification”: dimensions of epistemic evaluation. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Audi, R. (1978). Psychological foundationalism. In R. Audi (Ed.) (1993), The structure of justification (pp. 49–71). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bergmann, M. (2004). What’s not wrong with foundationalism. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 68(1), 161–165.

Brandom, R. (1994). Making it explicit. Reasoning, representing and discursive commitment. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Engelsma, C. (2014). On Peter Klein’s concept of arbitrariness. Metaphilosophy, 45(2), 192–200.

Ginet, C. (2005). Infinitism is not the solution to the regress problem. In M. Steup & E. Sosa (Eds.), Contemporary debates in epistemology (pp. 140–149). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Howard-Snyder, D. (2005). Foundationalism and arbitrariness. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 86, 18–24.

Howard-Snyder, D., & Coffman, E. J. (2006). Three arguments against foundationalism: arbitrariness, epistemic regress, and existential support. Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 36(4), 535–564.

Huemer, M. (2003). Arbitrary foundations? Philosophical Forum, 34(2), 141–152.

Huemer, M. (2010). Foundations and coherence. In J. Dancy, E. Sosa, & M. Steup (Eds.), A companion to epistemology (pp. 22–32). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Klein, P. (1998). Foundationalism and the infinite regress of reasons. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 58(4), 919–925.

Klein, P. (1999). Human knowledge and the infinite regress of reasons. Philosophical Perspectives, 13, 297–325.

Klein, P. (2000). The failures of dogmatism and a new pyrrhonism. Acta Analytica, 15(24), 7–24.

Klein, P. (2004). What is wrong with foundationalism is that it cannot solve the epistemic regress problem. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 68(1), 166–171.

Klein, P. (2005). Is infinitism the solution to the regress problem? In M. Steup & E. Sosa (Eds.), Contemporary debates in epistemology (pp. 131–140). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Klein, P. (2007). Human knowledge and the infinite progress of reasoning. Philosophical Studies, 134, 1–17.

Klein, P. (2012). Infinitism. In A. Cullison (Ed.), The continuum companion to epistemology (pp. 72–91). New York: Continuum International.

Leite, A. (2005). A localist solution to the regress of epistemic justification. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 83(3), 395–421.

Millar, A. (1991). Reasons and experience. Oxford: Clarendon.

Norman, A. (1997). Regress and the doctrine of epistemic original sin. The Philosophical Quarterly, 47(189), 477–494.

Plantinga, A. (1993). Warrant: the current debate. New York: Oxford University Press.

Pollock, J. (1974). Knowledge and justification. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Pryor, J. (2000). The skeptic and the dogmatist. Noûs, 34(4), 517–549.

Quinton, A. (1973). The nature of things. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Rescher, N. (1959/60). Choice without preference. Kant-Studien, 51, 142–175.

Rescorla, M. (2009). Epistemic and dialectical regress. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 87(1), 43–60.

Thomson, J. J. (2008). Normativity. Chicago: Open Court.

Turri, J. (2009). The ontology of epistemic reasons. Noûs, 43(3), 490–512.

Ullmann-Margalit, E., & Morgenbesser, S. (1977). Picking and choosing. Social Research, 44(4), 757–785.

Acknowledgments

My research is funded by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO), grant 360-20-281. For valuable comments on previous drafts, I thank Jeanne Peijnenburg, Jan Albert van Laar, and the members of the Groningen research colloquium in theoretical philosophy. I also thank the audiences of my talks at the University of Groningen (April 2013) and the University of Eindhoven (August 2013). For discussion of my thoughts at the workshop on infinite regresses at Vanderbilt University (October 2013), I especially thank Michael Rescorla, Selim Berker, Mylan Engel, Jeremy Fantl, René van Woudenberg, Scott Aikin, and Peter Klein. Finally, I thank an anonymous referee for this journal for comments that helped improve the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Engelsma, C. Arbitrary Foundations? On Klein’s Objection to Foundationalism. Acta Anal 30, 389–408 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12136-015-0257-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12136-015-0257-9