Abstract

This study analyzes narratives of cyber-porn users and defines major patterns of distress as self-reported by contributors to a self-help group in the Internet. It applies narrative analysis methodology to 2000 messages sent by 302 members of an Italian self-help Internet community for cyber-porn dependents (noallapornodipendenza). This paper focuses directly on the narratives of cyber-porn dependents, as they define themselves to analyze the major patterns of distress and characterize the extent and manifestations of their self-defined dysfunction. According to these testimonials in the collected messages, we should suggest that cyber-porn dependence is for many a real mental disorder that can have destructive implications for personal well-being, social adaptation, work, sex life and family relations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In contrast to purchasing pornographic magazines and videotapes or sex with prostitutes, the Internet has several features which make it an ideal medium for anonymous sexual activity. It is widely and easily accessible from almost any location. It is cheap, available in the privacy of one’s own home or office, insures secrecy and does not compromise the user’s social image, because these activities can be hidden from family and friends (Cooper et al. 2000a; Thomas 2004). The factors that make sex on the Internet a powerful medium include, among other things, accessibility, affordability and anonymity. This triad has been referred to as The Triple A Engine (Cooper 1998a). Moreover, the Internet has created a huge variety of sexual activities, not only pornographic picture libraries, videos and video clips, live strip-shows, but also chat-rooms, live sex shows and voyeuristic Web-Cam sites. It would also appear that virtual environments have the potential to provide short-term comfort, sexual affairs, uninhibited excitement and/or distraction. These aspects of Internet sex, moreover, might prove to be an advantage for such disenfranchised groups as homosexuals (Griffiths 2004, p.200), lesbians, bisexuals, transgenders and rape survivors (Cooper et al. 2000b).

There have been a few studies of excessive Internet use that have found a small proportion of users who admitted using the Internet for sexual purposes (Young 1998; Cooper et al. 1999b; Cooper et al. 2000a; Schwartz and Southern 2000). Researchers investigating the addictive potential of the Internet have noted the correlations between time spent online and negative consequences reported by users (Cooper et al. 1999c). They found that compulsive cybersex respondents are those who spent an average of 10 to 25 hours per week pursuing sex online (Cooper et al. 2000a, p. 8), and stressed that this group reported higher levels of distress around their online pursuits (Cooper et al. 1999a).

When compulsive sex use on the Internet reaches such weekly averages, it clearly decreases the user’s involvement, care, and availability to his family, and can negatively impact on marriage and sexual relationships, not only in cases of virtual infidelity (Schneider 2000a, b). The negative side of this activity may have troubling implications at the workplace (Cooper et al. 2002).

Popular-scientific studies suggest dysfunctions on the intrapersonal level that include loneliness, shame, boredom, depression, social isolation, impotence, powerlessness, anxiety, and the withdrawal-tolerance symptoms of addiction (Young 1998; Greenfield 1999). Most of these symptoms have been found by other clinicians who stated that “most clients (inpatients and outpatients) who use cybersex addictively also display signs and symptoms of the more pervasive sexual/behavioral compulsivities” which included, among other things, addiction tolerance and withdrawal symptoms (Orzack and Ross 2000, p.115).

Cooper identified five hallmarks of sexual compulsion that appear to be particularly prevalent in online users: denial, unsuccessful repeated efforts to discontinue the activity, negative impact of the behavior on social, occupational and recreational functioning and repetition of the behavior despite adverse consequences (Cooper 1998b).

Excessive Internet use and its relationship with sexuality have been divided by Griffiths (2004) into online sexual addiction, Internet and computer addiction, and online relationship dependency and/or virtual affairs. Griffiths found that these behaviors have implications for mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, and relapse (see also: Griffiths 1996). He argued that any behavior related to Internet abuse which fulfills these criteria can be operationally defined as an addiction. Moreover he stressed that there is certainly enough evidence that online sexual activity can cause major negative consequences to a small minority of users and that, for the majority of these individuals, their behavior resembles an addiction as most people would understand it. On the other hand Griffiths also indicated that it must be noted that collected data do have methodological limitations (the use of a self-selected sample, clinical samples of those who come in for treatment, self-reports by the partners of Internet sex addicts, reports by treatment providers, etc.).

This paper, circumventing statistical surveys and clinical reports, will try to map the common symptoms reported by an Italian group of male surfers, who define themselves as dependent on sex in the Internet (noallapornodipendenza site: http://www.noallapornodipendenza.it/index.htm). Notwithstanding the differences in the professional terms “abuse,” “addiction,” and “compulsivity” and their different pathological implications, this paper uses the term “dependence” based on the self-definitions of the participants themselves.

If surveys are correct, between 6–10% of Italian male surfers indulge in compulsive sexual activities on the web (La Repubblica Correspondents 2002), a figure similar to what has been found in the US (see for example: Cooper et al. 1999b, p. 83). But how do these surfers recount their stories, describe their experiences, and create their particular narrative? An innovative approach can be seen in an idiosyncratic qualitative methodology, which includes the participants’ reports juxtaposed with the stories of other members of the group. This approach should capture emotional expressions, subtle nuances beyond words, utterances, accessing “subject matter over which the speaker has command” (Goffman 1981, p. 187).

This research aims to analyze histories of distress and suffering, as recounted by participants in a self-help group, and to identify major symptoms of their self defined dysfunction. This study is an opportunity to collect and analyze the testimonials of cyber-porn dependents first hand, and to indicate pathological states among part of the population of participant.

The Character of the Italian Self-help Forum

An Internet self-help group is more than suitable for this purpose, in particular one that eschews professional involvement and interpretation and the mediation of empirical statistic research. The members of an Internet self-help group do not meet in a concrete physical arena, such as the town square or the ancient forum or agora, but rather interact in a crowded and intensive virtual space where they can express opinions and emotions directly without intermediaries, and where the forum elicits intense human feelings and networks of personal relationships (Rheingold 1994). Therefore Cooper’s (1998a) Triple A Engine characterized by accessibility, affordability, and anonymity can also be co-opted for the benefit of this space: “Any time there is a need, individuals can use these forums to write out thoughts and feelings, knowing that others will see what they write and may respond” (Cooper et al. 1999b, p. 96).

According to a few scholars, the web can be helpful for clinicians who should combine “e-mail, interactive video, and face-to-face treatment, integrated with the use of online education and group social support” (Putnam and Maheu 2000, p. 107). For others, the intervention of professionals is not necessary. Immediacy, simplicity of form, and lack of face-to-face interaction do not detract from the social impact of these exchanges. As scholars have argued, anonymity is often valued because it creates opportunities to reveal one’s true self and to engage in genuine, authentic forms of interaction, expressing aspects of personality that social inhibition would generally encourage one to suppress (Baym 1995). Recently, various studies of self-help groups on the Internet for disenfranchised communities based on sexuality have become available (Durkin 2004; Sanders 2008, pp. 79–87).

Analyzing a self-help group on the Web for the porn-dependent provides first-hand material about the problem, and thus avoids academic and professional interpretation, designation, pruning, classification etc. As stressed, the Italian noallapornodipendenza support group on the Internet was the primary source for the current study. In fact this site satisfies the prerequisites for this research: it explicitly encourages people to recount personal stories and show their feelings. Moreover, the site expresses a basic attitude of caution and even criticism as regards professional experts. From the very beginning the members were invited by the moderator to be sincere, speak their minds, and describe their distress in their own words. They were encouraged to detail their trial and error attempts to define, cope with, and overcome their problems and share this with the group. Furthermore, the homepage of the site has a special link dedicated to bad advice given by Italian professionals, who, according to the moderator of the site, usually do not understand the nature of the dependency and the members’ subjective personal experience of suffering (see the link: http://www.noallapornodipendenza.it/esperti.htm).

The general attitude of the site is the need to constantly search for new strategies to understand this “new disease”. In this sense the participants have gradually created their own internally developed narrative, body of knowledge, and intervention techniques, based on their personal experiences. As Rappaport stated (1994), the formation of an inner narrative can become a genuine antidote to monopolistic professional discourses.

The Genesis of the Forum

On April 23, 2003, “Marco”, whose nickname was also Ulisseuno 2003, started the Italian support group site on Yahoo! called noallapornodipendenza (transliterated loosely as nopornodependence). In his brief first message he stressed four points related to cyberporn dependence:

-

1.

“Ours is not an aberration, rather it is a specific mental illness, with clear causes, studies and research on the issue and real remedies.”

-

2.

“Many of us have this disease, but in particular in Italy people are not used to talking about it, probably because it is perceived as a sign of lack of sexual health, a lack of masculinity and (misplaced) eroticism.”

-

3.

“We can escape from dependence, but we need to know much more about ourselves, and what pornography represents for us...”

-

4.

“Porno-dependence gives us strong and comfortable emotions: in order to get rid of them we need to find other emotions, stronger emotions, [they are stronger] because [they are] nicer, more human and more in harmony with our spirituality.”

(Marco, message 1 in: http://www.noallapornodipendenza.it/index.htm).

Thus, from the very beginning, the founder drew on his dramatic experiences to assert that porn dependence is real, widespread, and pathological. In his subsequent messages “Marco” encouraged participants to be sincere, speak their minds, and share their suffering in their own words. In particular he asked them to speak out about their trial-and-error attempts to define, to cope with and overcome their distress.

The first to join was “Guido” who, when he discovered the new site, exclaimed that “There are other people. I’m not alone... I can say things and be understood, really understood by people going through the same thing” (# 3). Less than three weeks later (May 11, 2003), the group already had 35 members. By the middle of that summer, the site had reached a peak of more than 700 messages per month, with a total of 265 members (July 17, 2003). By April 1, 2005 the group had become a virtual community numbering one thousand members, and a hundred thousand visitors. Today (August, 2007), after two and half years of activity, the group has 2575 registered members. Noallapornodipendenza had an average of 270 messages per month in 2006. From the year 2005 on, members of the site’s self-help groups started to have face to face encounters all over the country, and recently spouses have started to take part.

The vicissitudes of “Marco”, or Ulisseuno (literally Ulysses one), the founder, are very different from those of the mythical Ulysses, who dramatically lost all his companions during his journey, and had to conceal his identity when he returned to his beloved Ithaca. “Marco,” whose real name is Vincenzo Punzi, indeed set sail, and gradually outed himself with his real identity, image, career profile, and phone numbers. He agreed to be interviewed by national weekly magazines such “Panorama” and appeared, undisguised, on top-rated popular TV programs like “Le Iene” (Italia Channel 1) and Piazza Grande (RAI Channel 2). He has also published a testimonial about his personal experiences as a porn-dependent in a recent book (Punzi 2006).

Methodology

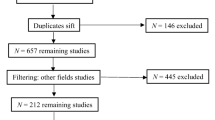

This study reports on a narrative analysis of two thousand messages written by 302 members of an Italian self-help group for cyberdependents (noallapornodipendenza). It sampled 400 messages from each year (2003–2007). Between 30–50 messages each month of each year were analyzed.

Out of a total population of 302 participants sampled, 85% are heterosexual adult males, with an average age of 32. Most are college students, or single men with academic degrees, white-collar professionals (such as business administrators, managers), teachers, and members of the liberal professions (computer technicians, engineers, architects, economists, paramedics, etc.—see occupational similarities in Cooper et al. 2000a). Their lifestyle gives them 24-hour free access to the Internet (either to sex activities or to the self-help forum). In the sample, the research found five cases of members who reported previous addictions (two cases of cocaine and heroin, two ex-alcoholics and one case of multiple addictions, gambling included), one case with a history of child abuse, two cases of severe physical disability, three cases of mental co-morbidity (depression with insomnia), and six cases of bisexual and homosexual activities in cyber-porn and real life. It seems that these figures, taken with some caution, run counter to other researches, which stressed higher figures of previous trauma, co-morbidity and other addictions among “compulsive cybersex abusers” (see for example, Schwartz and Southern 2000, p.132).

The sample also included fifteen cyber-porn addicted women who take an active part in this site, and thirty spouses and live-in friends of the cyber-addicted, whose participation in the site was welcomed by the moderator and by the members from the very beginning. These testimonials have been collected by the moderator in a specific link in the homepage: http://www.noallapornodipendenza.it/la%20donna%20del%20pornodipendente.htm).

The open, tolerant dialogue established between addicted women, spouses/live-in-friends, and addicted males created a positive dynamic, which deserves a separate study. This work will quote a few testimonials of these women when this complements the narratives of the male counterpart.

The male members have good Internet and computer skills. Most of them work with the Internet, at home or in their offices. As early as the mid-1990s, these qualified surfers quickly discovered pornography on the Web, and the use of firewalls or parental control devices became ineffective for most of them. The temptation to steal the ‘forbidden fruit’ by breaching filters (in Italian slang “craccare”) became part of the exciting game for many (see messages on this topic #16356–16367). Thus, their experience, skill, and lifestyle made them more likely to find support and resource-sharing within this same virtual reality. The testimonials of many members bear this out: “As usual I was surfing and searching for new porn sites, when I found your link and discovered that there are other people like me. I am not alone and I am already feeling better.”

The sample in this study is indicative of the highly educated, intelligent middle-class of Italy, characterized by broad cultural horizons. The nicknames are original and peculiar, and the style of the messages indicates a rich, well-constructed vocabulary in Italian, with hardly any spelling or grammar mistakes. The content is verbally dense, with no run-on sentences, and shows a good capacity to express emotions, insights, and to formulate arguments.

This paper employed narrative analysis (Berger 1997, pp. 4–14; Fairclough 2001) and an interpretive approach (Riessman 1993; Agar and Hobbs 1982). By using coding procedures that clustered sentences in the messages in analytically relevant ways (Grinnell 1997), similarities in the messages were mapped and conceptual themes and patterns were identified. This process will buttress the interpretation of symbols and concerns about issues related to porn dependence and the main issues of mental and physical distress of the participants.

Narrative analysis aims at understanding cognition, culture and community. It has been defined as a field that is emerging from several disciplines as a way to understand human experience, memory, and personal identity from the point of view of a person within a social context. In its simplest form, the narrative approach means understanding life to be experienced as a constructed story (Rappaport 1994). As Ken Plummer points out, the narrative may tell of a form of suffering that previously had to be endured in silence or may indeed not even have been recognized at all (Plummer 1995).

On a methodological level, the study of this site should be regarded with some caution, since those participating are not a representative sample of the population at large. Not everyone is likely to enter the arena of the self-help group (Cooper et al. 1999b, p. 96). A further methodological limitation is that this study has no control over the characters that interact in its “laboratory;” it has no way of classifying and cataloging the research sample. It is very likely that a few respondents may send many different messages, use different nicknames, or provide personal information to pose as someone he is not. Of course, hackers, agents provocateur and other participants faking or pretending a disease can also infiltrate this site.

The Individual Psychological Processes in Cyber-porn Dependence

It is more than natural and logical that appropriate recreational users, were not found as active members in the self-help group. They are those who access cybersex and do not experience any obsession, compulsion, or consequence as a result of their cybersex use (Delmonico 2002), and are designated also as non-sexually- or moderately sexually-compulsive respondents (Cooper et al. 2000a) or non- pathological users (Cooper et al. 1999b), In fact, this research identified two other sub-groups on the basis of different processes of cyber-porn compulsivity/ abuse/ dependence/ addiction.

The first group can be defined as cyber-porn dependents by a process of escalation. This group is also defined in the literature as a lifelong sexually compulsive group, composed of those who have had to cope with sexual addiction in other forms throughout their life, and the Internet simply becomes one additional way of acting out their inappropriate behaviors (Delmonico 2002). This group is mostly characterized by a history of isolation and solitude since childhood (“vincenzo” #5043). These are usually younger members who report their disease as a natural result of ongoing, sometimes compulsive masturbation, which started in their pre-adolescence. The advent of the Internet in the mid-1990s provided a newer, cheaper, faster, and more secret way for their auto-erotic expression. Most of them complain about compulsive sexual auto-eroticism, insecurity with women, lack of self-esteem and a sense of physical and mental inferiority. The story of this linear progress is well expressed by the following message (“the wall” #3510):

Probably a few of these mental dynamics started in my childhood. I remember having sexual thoughts at the age of 5/6. I was obsessed by photographic eroticism, erotic prose, and later, by pornography, first off-line and later on-line. First I was masturbating with vague indistinct thoughts, not related to sexuality. From the age of eleven, twelve and thirteen, very slowly ... I started to be obsessed, but in an introverted hidden way, with a heavy mark of shame because of my behavior... feeling I was doing something erroneous, abnormal... I was a bad pupil, I stuttered... I lived with a real psychological disease... which is still influencing my life... I started looking for sex on TV late in the night, purchasing Japanese comics, I was still living my own hidden world that started and terminated only inside myself, which kept me apart from others. Probably the erotic/pornographic material ruined my life, and probably I will never be able to have a normal, sentimental or sex life.

This particular group is typified by patterns of shyness, introversion, low self-esteem, and ongoing social isolation. The Italian slang term sfigato (unlucky or rejected sexually) is used frequently. This group is also composed of students who instead of studying are hooked on the Net, and procrastinate or neglect their academic commitments. A student wrote that he had been deceiving his parents for a year, pretending to work on his dissertation, while actually surfing cyber-porn sites day and night. For many their condition is reminiscent of an addicted escalation with new levels of tolerance. Many of them in fact search for increasingly more explicit, bizarre and violent images, bestiality included (“devorivivere” #2097).

The second group can be defined as having a double life. This situation is depicted by a few members as a life in two sealed chambers (compartimenti stagno) (“vincenzo” #5043), or as a member put it “living like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” (“lafcade” #8010). They are generally older, with more experience in heterosexual relations. About 5% state they are married or live with a partner. A few have children. They mostly complain about a dramatic change in their life that occurred when they discovered the Internet, sometimes parallel to and sometimes as a result of a stressful event in their lives (separation, divorce, breakups, unemployment, etc.). According to Delmonico (2002), this can be defined as a predisposed group, consisting of those who have had some history of problematic sexual fantasies, but for the most part have kept their urges and behaviors under control. Other scholars define this group as “at-risk users...who do not have histories of sexual compulsivity. However, their online sexual pursuits have caused problems in their lives” (Cooper et al. 1999b, p. 88). The Internet serves to foster the development of an already out-of-control sexual fantasy or urge that may not have developed into behavior until the introduction of the cybersex. The members of this group mostly complain about the gradual decline of their social and normal sexual lives, loss of contact with friends, colleagues and partners, and a growing lack of involvement and lower proficiency at work. In other words they are distancing themselves from their past identity. A 50 year old man castigated himself (“evergreen” #4427): “What am I doing [?], still masturbating like an adolescent, instead of talking with my wife?”

Many members complain about increased impotence and lack of ejaculation (“clockwork” #5020), feeling in their real life like “a dead man walking” (“vivalavita” #5014). The following example concretizes their perceptions (“sul” #4411):

My erotic relation with my spouse was disappointing....With the opportunity to be contacted on-line, I started to surf... Later I started to chat on eroticism... I kept my wife out of all this... In the meanwhile, other women appeared on the scene... from an exciting playful game, in one year my visits to erotic chat rooms became a real obsession, I stayed up at night... masturbating in front of the PC. I used to work during the day and masturbate at night... My work started to be affected... I was tired in the daytime...My wife caught me....She did not leave me... but she will never forget... I have betrayed and humiliated her; I have shared my intimacy in such an obscene way with strangers...

There were also cases in this group of compulsive masturbation, addiction tolerance, combined with a severe isolation from real life. Many of these participants can be defined as “at-risk users/stress reactive types” (Cooper et al. 1999b, p. 90). The following case of severe addiction of a young adult is not unusual (“filippo” #4754):

Since I installed my Internet, chatting and browsing porn videos has been my only occupation during the day. I start the morning by visiting news... in the forum, then I start to download. I have states of euphoria when my browsing is fast and of mild depression when there is nothing new. In the afternoon, it is the same... in the evening I select the best material for my archive and delete everything I don’t need... A good day or a bad one depends upon the number of megabytes I am able to download. All this has ruined my social life. The only positive point is that I have a girlfriend... but with her I almost always fake my orgasm, or I fake pains justifying my [giving up and] going back to my screen. Today I don’t work, I quit two jobs because they didn’t give me enough time to spend in front of the screen...

The distinction between two groups of male dependents is thus based mainly on the nature of the addiction process. It should be stressed that at times the two processes can overlap, with a history of social isolation during adolescence, then a problematic romantic relationship or marriage, and later, falling back into a life of stress, depression, social isolation, and cybersex abuse.

Narratives of Distress

The symptoms and the coping strategies in the community members’ narratives are highly similar, and in this context the division into two different groups becomes irrelevant. This section will present and discuss the most typical and significant narratives related to the suffering of this group (strategies of coping and recovery of members of this community are analyzed in another study: Cavaglion 2008a, b).

Total Breakdown of Self-esteem

This dynamic is well expressed by the moderator (“Marco” #222):

Our battle is conducted through our eyes...we are exposed to thousands of images with our penis in continuous tension...then tired, confused, humiliated, deprived of our own self-esteem, in an attempt at self conservation, we finally decide to ejaculate, [so as] not to go mad, not to die. And the tension, the anguish and the anger collapse vertically. And those images that hooked us for hours... lose their life, lose any form of attraction. Insane, ridiculous, absurd.

In another message a member desperately announces that the true state of consciousness is lack of self esteem, therefore: “I didn’t have any right to live. No place for my deepest spiritual needs” (“marco2” #4004). This lack of self-esteem is also expressed by hundreds of self derogatory attributes related to inner decay, filth and excrement: “I feel dirty” (“elvinjones” #4195), “I feel rotten inside” (“kronor” #4743), and also terms such as “disgusted with myself, I am sick of myself” etc. For many, a common metaphor takes a scatological form: “feeling like sh-t,” “being stuck in a sewer,” etc. (“vincenzo” #12035). Many similar terms can be seen as part of living in a world of excreta and secretions, and grotesque male degradation typical of pornography in general (see discussion in Langman 2004).

Other terms are taken from other specific jargons and metaphors. Among these are:

-

1.

Demonization: The use of demonic terms in the discussion of social deviance is still commonplace today and perhaps even more so in Catholic countries like Italy. The prime road to demonic deviance, the road to temptation, is one in which humans are afforded some measure of choice. Yet, following the ancestral fall from grace, they are said to be weakened and susceptible to seduction by the multiple forms taken by the devil (Pfohl 1985). The second road to demonic deviance is the road of possession. A possessed person is believed to be literally taken over by the devil or by some evil spirit. Once possessed, a person may be viewed as no longer responsible, and no longer able to choose between good and evil, sin and conformity (Pfohl 1985). Demonic themes can be found in the messages, as for example: “I am becoming a monster” (“sonoio” #2073); “We are possessed by the devil [i.e. the personal computer]” (“marco”, the moderator #76); “We made a pact with the Devil...who stole your soul, by giving you whatever you want” (“w4 × 3l” #73). Or in a more mythological frame: “[Cyberporn is] like Medusa—you must never look at her” (“marco” the moderator #4008). In other words, many participants assume that cyber-porn has some magical and powerful influence on their minds. An evil spell (maledizione) has influenced their lives.

-

2.

Sickness and Insanity: These narratives are a more sophisticated way to designate forms of social deviance. Their foundation is science and not faith. They stress the absence of guilt, and emphasize treatment and rehabilitation rather than punishment for a so-called sin (see discussion in Kittrie 1971). The pathological model has an element of “moral neutrality,” where the victim is exempt from normal responsibilities and direct responsibility for his condition (Conrad and Schneider 1980). As the sociologist Pfohl stressed, pathologically defined rule-breakers are able to avoid blame and shun responsibility; those included in this group cloak themselves in the false garb of moral neutrality (Pfohl 1985). A few participants claimed that cyber-porn probably had some subliminal, hypnotic, cunning, or enticing influence. In other words, the individualization of their problem on a pathological level assumes the function of a “sickness” which may remove blame and responsibility (Halleck 1971). These themes are also present in the following quotes “PD [porn dependence] is a very new disease, like AIDS and SARS, it is immediate... endemic... it spreads easily and fast” (“devorivivere” #2094). “This compulsion is like herpes, it remains in your body” (“ammin” #15559). “Giving up without a fight is now part of our DNA” (“marco” the moderator #3783). “It is like a migraine headache that’s so bad you can’t control yourself” (“devorivivere” #2094). “It is as though part of my body is sick and influences all the other parts that are trying to live” (“boescape” #3517). And also: “It is like an allergy” (“adriano” #2243).

The self-definition of being sick can reduce shame, but can also instill hope among the participants. This point was stressed in the mediator’s initial message: “Ours is not an aberration, rather it is a specific mental disease, with clear causes, studies and research on the issue and real remedies” (“marco” #1 [italics added]). The theme of mental illness is more frequent: “We are nuts (mentecatti)” (“marco” the moderator #3514); “My brain is like custard” and “I am a neurotic” (“rosariobene” #3599); “I am a slave of orgasm” (“marco2” #76); “I am in a brain warp” (“sonoio” #2073); “I need a dose of daily porn” (“effemmerre” #3528). “I have a Peter Pan Complex” (“alberto” #2968); “You have to think that you are suffering from a terrible disease... which traumatized your psyche” (“marco” the moderator #4203); “Our brain is sick, lazy, poisoned by huge quantities of free endorphines” (“vincenzo” #5029).

In many cases the members adopt an updated physiological theory of neurotransmitter dysfunction in the brain. Words like physiological craving, endorphines, and dopamine are common.

Progressive Lack of Confidence in One’s Ability to Manage His Life

Many surfers stated that they felt they were losing control over their lives, and were unable to manage their day: “I cannot finish anything” (“rosariobene” #3599); “I am stuck in a whirlpool” (“boescape” #3517); “Porn dependence is the alibi for the novel I am not writing” (“marquez” #4737). For many this feeling is also caused by the huge costs associated with their addiction. The following story concretizes the secondary financial loss (“paneintegrale” #5686):

I have made a quick calculation: in this “activity” I spend almost 36/38 hours a week, 150 hours a month, 1800 hours a year. I am a freelancer, and [paid] 30 Euros per hour—this little toy costs me 54 thousand euros per year. This little toy has lasted for 8 years... that is at least 432 thousand Euros... this is madness!!!

Lack of Concentration and Lower Proficiency at Work or at School

As stressed in the introduction, one of the most troubling ramifications on the interpersonal level stems from the large amount of time spent on the computer, which becomes detrimental at the workplace (Cooper et al. 2002). Many surfers claim they experience addiction withdrawal at work or at home that usually manifests itself as physical tiredness and mental irritability (“lvbenci” #4187). For others it appears more like the Gestalt paraphrase of unfinished business: “I cannot finish my studies” (“mandriano” #2559); “I cannot submit my dissertation” (“devovivere” #3600); “I am all dried up” (“bruja” #2904); “Today I do not have other interests, I don’t study anymore, I work the minimum” (“fellos” #94). Many surfers talked about a sense of existential lethargy, powerlessness and helplessness: “I am spineless” (“mandriano” #2559). This existential attitude to time and life is reminiscent of the following passage by Erich Fromm (cited in von Franz 2000, p.64):

If one believes in Time, then one has no possibility of sudden change, there is a constant expectation that “in time” everything will come all right. If one is not capable of solving a conflict one expects that “in time” everything will come all right, one expects that “in time” the conflicts will solve themselves, without one having to risk a decision. You find that very often, especially in believing in time as far as one’s achievements are concerned. People comfort themselves, not only because they do not really do something but also for not making any preparation for what they have to do, because for such things there is plenty of time and therefore there is no need to hurry. The older such people get, the more they cling to the illusion one day they will do it. In certain people the reaching of a certain age, brings a sobering effect so that they then begin to use their own forces, or there is a neurotic breakdown which is based upon the fact that one cannot live if one does not have that comforting time illusion.

Progressive Isolation from the World Outside

In their research, Schwartz and Southern found that focus on the computer, as a “dissociative reenactment,” can put people in a trance-like state and help them to ignore “past conflicts or traumas with underlying motives to resolve unfinished business” and outside events and emotions that they don’t want to experience (2000, p. 129). For many surfers the cyber-porn world is perceived as a world of fantasies, which causes a sense of aloofness, numbness, dissociation and isolation from real life. As stressed by a participant: “in cyber-porn dependence there are havens, tranquility and relaxation, there you can deal with your heart and your mind, and nobody will spy on you, you don’t have to cope with others’ sentiments” (bjorkanto #2974). The messages indicate a loss of the important value of the here-and-now and, with it, the psychological functions of feeling. Feelings impart a meaning to the present, for without feelings one has no relationship to the here-and-now situation, and with it comes responsibility, and hence a structured adult individual. For example, a message stressed that their condition of cyber-porn dependency “is a rite of childish omnipotence of grown up boys who do not want to come to terms with real life and its relationships” (“benco4” #201). A very severe case was reported by an adult male, who spent two consecutive days and nights on the Internet, eating, drinking and urinating in front of the screen. After that, he started suffering from insomnia and hemorrhoids (“vinicio” #14091). This is a very regressive mental state, similar to a primitive retreat into the womb. As another participant stated, he still feels like he is living in a bubble or in a placenta (“boooh” #1409).

Not surprisingly, for this group of cybersex dependents, coming out and declaring their distress can be very difficult, because of their regressive state and social isolation. Moreover, they perceive themselves as being doubly deviant: on the one hand they feel they are suffering from a new and undefined disease, and on the other, they feel abnormal, guilty, and ashamed of their addictive consumption of pornography and their frequent and compulsive masturbation in adulthood. For many people, being in psychological treatment, visiting a “shrink” may be perceived as a further deviance, especially when the problem of internet addiction in general, is still too new for consensus in the professional and academic establishment as regards diagnosis and treatment (Morahan-Martin 2005; Griffiths 1998). Therefore, also for this reason, an anonymous self-help group in the Internet can be very beneficial for many (Cooper et al. 1999b, p. 96–97).

A Painful Sensation of Seeing Life Fade Away

Many surfers report a sensation of terminal time warp, a phenomenon that almost all Internet users experience at some point in their on-line travels, coupled with embarrassment or even alarm at how much time they spent when they went on-line for a few minutes (Young 1998). As one participant said: “It felt like two minutes, but I wasted one and a half hours doing nothing” (“harlot” #4134). This feeling of wasting one’s time is more dramatic when this problem extends to the participants’ whole life, with such descriptions as: “I am frittering away my time on the screen” (“jack” #216). “I feel parched, having lost moments in life that will not come back again” (“inpanne” #196). “We are not living how we would like to live. We have denied ourselves those essential emotions for our survival” (“marco” the moderator #89). “We are fucking our youth” (“rosariobene” #3599). “I have wasted hours in my life for nothing” (“notte” #120). There are even notions of ongoing self-destruction: “I am a terminally ill person who is waiting to die” (“dam_09” #178), and “I am vegetating, not living” (“rosariobene” #3599).

The following message captures this feeling of a wasted life, and profound sorrow for the lost years (“violanavi” # 2170):

I fell into porn dependence seven years ago... I dumped into my mind about 100,000 pics or movies; I spent at least 5,000 hours of my very precious life in front of that damned screen; I masturbated with madness at least 500 times and I spent my precious sperm without... joy. And I told myself that all this has ravaged and distorted my mind, and poisoned my way of thinking.

While for many surfers the theme is wasting their lives, others stress the fact that they had never begun to live. Again, in Gestalt vocabulary this seems to be a problem of un-started business, a sort of “Waiting for Godot” syndrome. For example (“fenotipo” #3504):

We porn-dependent men, at least in my case, are basically adolescents, and children in our way of living even before being exposed to pornography... we live in fantasies, we give up important things in life... we are naïve, lazy... those sterile pictures where women and men do not smell, do not sweat... their secretions do not have any smell or taste, pictures shot in wonderful places... villas, swimming pools where they make love in parks or absurd places... they all become a surrogate to reality, but the real reality doesn’t belong to us anymore.

And also: “I am chasing after silly illusions” (“winner” #2060). As a 50-year-old member observed, in pornography “you only have to satisfy yourself, you learn to control your movements in order not to ejaculate, to consume [the images of] 100, 1000, 10,000 false women” (“Marcello” #15557).

This attitude is reminiscent of the Roman myth of the Eternal Child, the Puer Aeternus, who is enmeshed in unrequited pursuit of the beautiful and the poignant, yearning for union with the Mother from one woman to another (von Franz 2000). As Moore and Gillette stressed (1991, p. 36 italics in the text):

[This immature child] can never be satisfied with a mortal woman, because what he is seeking is the immortal Goddess... [he is] what is called autoerotic. He may compulsively masturbate. He may be into pornography, seeking the Goddess in the nearly infinite forms of the female body.... He is seeking to experience his masculinity, his phallic power, his generativity. But instead of affirming his own masculinity as a mortal man, he is really seeking to experience the penis of God—the Great Phallus— that experiences all women, or rather that experiences union with the Mother Goddess in her infinity of female forms. Caught up in masturbation and the compulsive use of pornography,[he] wants just to be. He does not want to do what it takes to actually have union with a mortal woman and to deal with all the complex feeling involved in an intimate relationship. He doesn’t want to take responsibility.

This attitude is consistent with the fact that many participants expressed a general devaluation of any real woman, whom they perceived as “less attractive than any surrogate porno star” (“ap_ibiza” #4200).

Many women who sent messages to the site expressed a similar feeling that they were living with an apathetic, aloof, isolated man who did not express any affection to them as a person or show sexual interest in their mostly imperfect bodies (see discussion in Schneider 2000a, b). The homepage of the site has messages from dozens of betrayed, offended, humiliated, desperate and neglected women “going crazy, afraid, and sick of all his lies” who found the site to be a channel for dialogue and self expression http://www.noallapornodipendenza.it/la%20donna%20del%20pornodipendente.htm).

Many of their testimonials buttress the narrative of specific maladaptive behavior among their male partners, in particular on the level of their relatedness, social involvement, ability to work and sex life. These descriptions contain various themes that were brought up by other scholars: a feeling of being objectified, comparing themselves with cybersex women, initial attempts to increase the quantity and/or variety of sexual activities, and a decreased desire to have sexual relations with the addict (Schneider 2000a). Moreover, in many cases women reported cases of online infidelity as the major causes of the male behavior (change in sleep patterns, a demand for privacy, evidence of lying, personality changes, etc.; see: Young et al. 2000, pp. 65–66).

Sexual Problems

Many participants stated that they usually spend hours looking at and collecting pictures and movies holding their erect penis in their hand, unable to ejaculate, waiting for the ultimate, extreme image to release the tension. For many the final ejaculation puts an end to their torture (supplizio) (“incercadiliberta” #5026). But for others masturbation is no longer the final goal. For example the compulsive collection of movies and pictures itself becomes the ultimate goal of pleasure (“paneintegrale” #5686):

I discovered my life was ruled by porn. Everything has to function according to it. My computers are maintained and updated to make more space for more movies. Antivirus and other protections are there to protect me when I download from unauthorized sites. The first thing I do in the morning is to make a list of automatic downloads and check dozens of movies ... on Sunday when I get rid of my family, I spend the day cataloguing the movies. If I have dinner with friends, later at night I go to my office to check if my computer is connected and is still downloading.

Others enjoy collecting and archiving for categories: “blonds, brunettes, large breasts, legs etc.” (“herman” #14456).

Problems in heterosexual relations are more than frequent. People complain they have erection problems (“nick” #19), lack of sexual relations with their spouses (“carlomiglio” #6), lack of interest in sexual intercourse, feeling like a person who has eaten hot, spicy food, and consequently cannot eat ordinary food (“enr65a” #205). In many cases, as also reported by spouses of cyber dependents, there are indications of male orgasmic disorder with the inability to ejaculate during intercourse. This sense of desensitization in sexual relationships is well expressed in the following passage (“vivaleiene” #6019):

Last week I had an intimate relation with my girlfriend; nothing bad at all, despite the fact after the first kiss I didn’t feel any sensation. We didn’t finish the copulation because I didn’t want to. You know what I am going to do? Run away. I am afraid... I feel completely inadequate... I am afraid to make an idiot of myself... I am afraid I will disgust her, not perform (in Italian slang: fare cilecca).

Many participants expressed their real interest in “chatting on line” or “telematic contact” instead of physical touch (“duke” #12580), and a pervasive and unpleasant presence of pornographic flashbacks in their mind, during sleep and during sexual intercourse (“vincenzo” #12269). As stressed, the claim of a real sexual dysfunction is echoed by many testimonials from female partners. But also forms of collusion and contamination appear in these narratives. Here are a few of the most striking comments of these female partners:

Making love is always poisoned by these stories, which I also see on the Web. Yesterday we made love without these stories but he did not have any passion, I felt it. I felt distressed, the pictures he showed me days before were popping up in my mind. I felt obliged to be like those women, to do what they do, otherwise I had the feeling I would not satisfy my man... I am afraid that we will never be able to make love without other thoughts (“Laura ballarin”).

And also:

Our way to make love is a real imitation of a pair of actors in the most obscene porn movie, there is no more tenderness, there is no more total contact of the bodies, only genitals, there is never a kiss or a hug (“Lucia gavino”).

Another woman states:

I am afraid that when he finally will get closer to me again, he will have all that garbage in his mind, and it will happen to me too (in an exciting and disgusting sense), this will happen because after I discovered his PC-archived images, sometimes I have flashbacks, I see them as if they are pasted in front of me, in such a vivid and disgusting way, will these images persecute me in my most intimate moments forever? (“pornobasta0505”).

Discussion

In the scientific literature the definition of “Internet addiction” has been challenged on several counts (see for example Morahan-Martin 2005; Griffiths 1998). One frequent argument is that a sexual addiction can be invented and monopolized by mental health professionals so that they can benefit by becoming the targets of designation and intervention by the hegemonic medical establishment. Other scholars may claim that there is a tendency to stereotype and over-generalize cybersex addiction as a “new disease” by also including a vast umbrella of symptoms that can be ascribed to any personal computer user. This led to the claim (albeit from a minority) that addiction in general is a new domain invented for the therapeutic industry (Peele 1999).

But for other scholars, sexually-related Internet behaviors appear to range from the healthy and normal to the unhealthy and abnormal (see for example the spectrum of, use, abuse, and addiction, Cooper et al. 1999b).

Although this study should be considered preliminary and its findings are subject to caution, what emerges is that the terms of psychopathological conditions or mental disorders are more than appropriate for the lifelong sexually compulsive and predisposed double life groups. It may be the case that more than one diagnostic category is valid for many participants. However, a sample of these dramatic testimonials suggests that we are dealing with forms of psychopathology that deserve real attention. Most of the messages sent to the Italian self help group do indicate the presence of pathology by those participants, according to the model of salience (in real life), mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal symptoms and interpersonal conflict, a diagnostic model developed by Griffiths (2004).

Moreover, the strict definition of pathology, as discussed in the DSM lists many of the reported features of distress, including disability and impairment in one or more areas of functioning, significantly increased risk of suffering and pain, and, more importantly, partial or total loss of freedom. According to scholars who tried to define the essence of psychopathology, if there is some personal discomfort, if people are distressed over their thoughts or behavior, there is a pathology (see discussion in Bootzin et al. 1993). Moreover, if a person manifests maladaptive behavior and is not able to meet the demands of his life, namely, hold down a job, deal with friends and family, pay the bills on time and the like, this pattern is also characteristic of abnormal behavior. Thus cyber-porn dependence, as reported by Italian participants in the self-help group, may indicate a maladaptive behavior which interferes with functioning and is self-defeating, since its outcomes, which are longlasting and severe, impinge on the continued well-being of the individual and that of the human community of which the individual is a member (see discussion in Carson et al. 1999).

In conclusion we should stress again that these results can be interpreted with some caution, because of the nature of the research and methodological. Further research is needed basing on a different and more empirically sophisticated methodology, and/ or basing on a follow up of the group and/or using a comparative analysis with similar groups in other western countries.

References

Agar, M., & Hobbs, J. (1982). Interpreting discourse: cohering and the analysis of ethnographic interviews. Discourse Processes, 5, 1–32.

Baym, N. (1995). The emergence of community in computer-mediated communication. In S. Jones (Ed.), CyberSociety: Computer-mediated communication and community (pp. 138–163). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Berger, A. A. (1997). Narratives in popular culture, media and everyday life. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bootzin, R., Acocella, J., & Alloy, L. (1993). Abnormal psychology. New York: McGraw Hill.

Carson, R., Buthcer, J., & Mineka, S. (1999). Abnormal psychology and modern life. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Cavaglion, G. (2008a). Narratives of self-help of cyberporn dependents. Journal of Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity, 15(3), 195–216.

Cavaglion, G. (2008b). Voices of coping in an italian self-help virtual community of cyberporn dependents, accepted for publication by CyberPsychology & Behavior (in press).

Conrad, P., & Schneider, J. (1980). Deviance and medicalization. St. Louis: C.V. Mosby.

Cooper, A. (1998a). Sexuality and the internet: surfing into the new millenium. CyberPsychology, & Behavior, 1, 187–193.

Cooper, A. (1998b). Sexually compulsive behavior. Contemporary Sexuality, 32, 1–3.

Cooper, A., Boies, S., Maheu, M., & Greenfield, D. (1999a). Sexuality and the internet: The next sexual revolution. In F. Muscarella, & L. Szuchman (Eds.), The psychological science of sexuality: A research based approach (pp. 519–545). New York: Wiley.

Cooper, A., Delmonico, D., & Burg, R. (2000a). Cybersex users, abusers, and compulsive: new findings and implications. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity, 7, 1–2.

Cooper, A., Golden, G., & Kent-Ferraro, J. (2002). Online sexual behavior in a workplace: how can human resource department and employee assistance programs respond effectively. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity, 9, 149–165.

Cooper, A., McLoughlin, I., & Campbell, K. (2000b). Sexuality in the cyberspace: update for the 21st century. CyberPsychology and Behavior, 3, 521–536.

Cooper, A., Putnam, D., Planchon, L., & Boies, S. (1999b). Online sexual compulsivity: getting tangled in the net. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 6, 79–104.

Cooper, A., Scherer, C., Boies, S., & Gordon, B. (1999c). Sexuality on the internet: from sexual exploration to pathological expression. Professional Psychology, 30, 54–164.

Delmonico, D. (2002). Sex on the superhighway: Understanding and treating cybersex addiction. In P. Carnes, & K. Adams (Eds.), Clinical management of sex addiction (pp. 239–254). New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Durkin, K. (2004). The internet as a milieu for the management of a stigmatized sexual identity. In D. Waskul (Ed.), Net.seXXX: Readings on sex, pornography and the internet (pp. 131–147). New York: Peter Lang.

Fairclough, N. (2001). Critical discourse analysis as a method in social scientific research. In R. Wodak, & M. Meyer (Eds.), Methods of critical discourse analysis (pp. 121–138). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Goffman, E. (1981). Forms of talk, Philadelphia. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania.

Greenfield, D. (1999). Virtual addiction: Help for netheads, cyberfreaks, and those who love them. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger.

Griffiths, M. (1996). Internet “Addiction”: an issue for clinical psychology? Clinical Psychology Forum, 97, 32–36.

Griffiths, M. D. (1998). Internet addiction: Does it really exist? In J. Gackenbach (Ed.), Psychology and the internet: Intrapersonal, interpersonal and transpersonal applications (pp. 61–75). New York: Academic.

Griffiths, M. (2004). Sex addiction on the internet. The Janus Head, 7, 188–217.

Grinnell, R. (1997). Social work research and evaluation: Quantitative and qualitative approaches. Itasca: Peacock.

Halleck, S. (1971). The politics of therapy. New York: Science House.

Kittrie, N. (1971). The right to be different. Baltimore: John Hopkins.

La Repubblica Correspondents. (2002). Sessodipendenza: ne Soffre il 5% degli Uomini Italiani. La Repubblica, p. 3 (in Italian), March 15.

Langman, L. (2004). Grotesque degradation: Globalization, carnivalization, and cyberporn. In D. Waskul (Ed.), Net.seXXX: Readings on sex, pornography and the internet (pp. 193–216). New York: Peter Lang.

Moore, R., & Gillette, D. (1991). King, warrior, magician, lover: Rediscovering the archetypes of the mature masculine. San Francisco: Harper.

Morahan-Martin, J. (2005). Internet abuse: addiction? Disorder? Symptom? Alternative explanations? Social Science Computer Review, 23, 39–48.

Orzack, M. H., & Ross, C. J. (2000). Should virtual sex be treated like other sex addictions? Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 7, 113–125.

Peele, S. (1999). Diseasing of America: How we allowed recovery zealots and the treatment industry to convince us we are out of control. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Pfohl, S. (1985). Images of deviance and social control: A sociological history. New York: McGraw Hill.

Plummer, K. (1995). Telling sexual stories: Power, change and social words. London: Routledge.

Punzi, V. (2006). Io Pornodipendente Sedotto da Internet. Milan: Costa & Nolan (in Italian).

Putnam, D., & Maheu, M. (2000). Online sexual addiction and compulsivity: Integrating web resources and behavioral telehealth in treatment. In A. Cooper (Ed.), Cybersex: The dark side of the force (pp. 91–112). Philadelphia: Taylor and Francis.

Rappaport, J. (1994). Narrative studies, personal stories, and identity transformation in the mutual-help context. The Journal of Applied Behavior Sciences, 29, 239–256.

Rheingold, H. (1994). The virtual community: Finding connection in a computerized world. London: Minerva.

Riessman, C. (1993). Narrative analysis. Newbury Park CA: Sage.

Sanders, T. (2008). Paying for pleasure: Men who buy sex. Portland: Willan.

Schneider, J. (2000a). Women of addicted cyberporn abusers. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity, 7, 31–58.

Schneider, J. (2000b). Effect on cybersex addiction on the family: Result of a survey. In A. Cooper (Ed.), Cybersex: The dark side of the force (pp. 31–58). Philadelphia: Taylor and Francis.

Schwartz, M., & Southern, S. (2000). Compulsive cybersex: The new tea room. In A. Cooper (Ed.), Cybersex: The dark side of the force (pp. 127–144). Philadelphia: Routledge.

Thomas, J. (2004). Cyberpoaching behind the keyboard: Uncoupling the ethics of ‘virtual infidelity’. In D. Waskul (Ed.), Net.seXXX: Readings on sex, pornography and the internet (pp. 149–177). New York: Peter Lang.

von Franz, M. L. (2000). The problem of the Puer Aeternus. Toronto: Inner City Books.

Young, K. (1998). Caught in the net. NY: Wiley.

Young, K., Griffin-Shelley, E., Cooper, A., O’Mara, J., & Buchanan, J. (2000). Online infidelity: A new dimension in couple relationships with implications for evaluation and treatment. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity, 7, 59–74.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cavaglion, G. Cyber-porn Dependence: Voices of Distress in an Italian Internet Self-help Community. Int J Ment Health Addiction 7, 295–310 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-008-9175-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-008-9175-z