Abstract

Purpose

The practicality of social footprinting is currently hampered by an excessive data requirement, a lack of focus on materiality of the impacts, and a lack of understanding of the main impact pathways (cause-effect relationships) for social and economic impacts. We propose a “streamlined” method to overcome these barriers without loss of comprehensiveness.

Methods

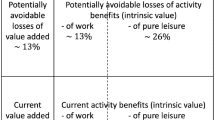

The method combines a top-down approach using input-output data to focus the data collection effort on processes with high value added or a high number of work hours with a streamlined impact assessment that limits the inventory data requirement and the need for detailed impact pathway descriptions, by focusing on the macro-scale impacts of income redistribution and productivity impacts of missing governance, both of which can be classified as nonproduction-specific impacts, i.e., unrelated to enterprise-specific actions and choice of technology, and therefore quantifiable from national statistics without need to access detailed technology- or enterprise-specific data. The method is open for further refinement and detail in areas of specific interest for a particular product or project.

Results and discussion

We show that nonproduction-specific impacts constitute the vast majority of social and economic impacts and how important income inequality is for the impact assessment. We apply a novel way of combining impacts on productivity and impacts on human well-being and show that inequality implies that an intervention that changes the amount of QALY (quality-adjusted life years) for a population group will always give a larger change in well-being than an intervention of the same monetary value that only affects the level of consumption of the same population group. Throughout the article, we apply and illustrate the method with an example from the clothing industry.

Conclusions

The presented method allows comprehensive assessments of social footprints of products at much lower efforts than seen so far. The potential credits for positive action is by far the largest in countries with missing governance, thus providing a compelling argument for placing activities in countries with missing governance, provided that it allows the enterprise to follow an active strategy to create shared value.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Work-place related impacts (e.g. health, labour rights violations, discrimination, missing pay and social security) can best be expressed in relation to working time, while impacts on the community (e.g. corruption, underemployment, missing tax and infrastructure payments) can best be expressed in relation to value added (Weidema 2006b).

Income includes both direct income as wages or entrepreneurial profit and indirect income via tax transfers, which together sum up to the value added.

It is an interesting question whether some of the difference in productivity should be ascribed to climate or other local conditions, also in a situation without externalities. Evidence presented by Dell et al. (2008) shows an effect of temperature on aggregate productivity for poor countries, but not for rich countries. Rather than a direct causal relationship between temperature and productivity, the adverse temperatures appear to aggravate other causes for low productivity. The question is therefore if such differences would persist in a situation without externalities (and therefore also without limitations on the movement of labour and with adequate income to provide temperature adaptation). If indeed they should persist, they would be related to variation in the work-leisure preference, i.e., the extent to which leisure is preferred to work or vice versa, and while such variation may affect the per capita GDP, it does not affect the productivity per work hour, which is what we are concerned with here. The same argument can be applied to any cultural differences in productivity that may remain after all externalities have been internalised.

The 21 % is calculated from a wage for household workers of 2.325 USD and 1312 h of unpaid work for each of the 73.7 % of the population above 15 years (Worldbank 2015).

References

Ahmad N, Koh S-H (2011) Incorporating estimates of household production of non-market services into international comparisons of material well-being. STD/2011/07. OECD, Paris

D’Ambrogio E (2014) Workers’ conditions in the textile and clothing sector: just an Asian affair? European Parliament Briefing. Brussels: European Parliamentary Research Service. www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2014/538222/EPRS_BRI(2014)538222_REV1_EN.pdf (Accessed 2015–07-30)

Andrews ES, Barthel LP, Beck T, Benoît C, Ciroth A, Cucuzzella C, Gensch CO, Methot AL, Moberg A, Hébert J, Lesage P, Manhart A, Mazeau P, Mazjin B, Norris G, Parent J, Prakash S, Reveret JP, Spillemaeckers S, Ugaya S, Maria L, Valdivia S, Weidema BP (2009) Guidelines for social Life Cycle Assessment of Products - UNEP SETAC life cycle initiative

Barro R J, Lee J-W (2010) A New Data Set of Educational Attainment in the World, 1950–2010. NBER Working Paper No. 15902

Benoit-Norris C, Cavan DA, Norris G (2012) Identifying social impacts in product supply chains: overview and application of the social hotspot database. Sustainability 4(9):1946–1965

Bocoum I, Macombe C, Revéret J-P (2015) Anticipating impacts on health based on changes in income inequality caused by life cycles. Int J Life Cycle Assess 20:405–417

Brown G (2012) Child labour & educational disadvantage – breaking the link, building opportunity. The Office of the UN Special Envoy for Global Education, London

Ciroth A, Franze J (2011) LCA of an ecolabeled notebook - consideration of social and environmental impacts along the entire life cycle. GreenDeltaTC, Berlin

Falque A, Feschet P, Garrabé M, Gillet C, Lagarde V, Loeillet D, Macombe C (2014) Social LCAs. Socio-economic effects in value chains. Montpellier: Fruitrop Thema, CIRAID. Copyright CIRAID 2013. English edition published 2014

Feschet P, Macombe C, Garrabé M, Loeillet D, Saez A, Benhmad F (2013) Social impact assessment in LCA using the Preston pathway. Int J Life Cycle Assess 18:490–503

Grießhammer R, Buchert M, Gensch C-O, Hochfeld C, Manhart A, Reisch L, Rüdenauer I (2007) Prosa – Product Sustainability Assessment Guideline. (PROSA 2.0). Freiburg: öko-Institut e.v. – Institute for Applied Ecology

Jørgensen A, Le Bocq A, Nazarkina L, Hauschild MZ (2008) Methodologies for social life cycle assessment. Int J Life Cycle Assess 13(2):96–103

Jørgensen A, Finkbeiner M, Jørgensen MS, Hauschild MZ (2010a) ) Defining the baseline in social life cycle assessment. Int J Life Cycle Assess 15(4):376–384

Jørgensen A, Lai L, Hauschild M (2010b) Assessing the validity of impact pathways for child labour and well-being in social life cycle assessment. Int J Life Cycle Assess 15:5–16

Kabeer N, Mahmud S (2004) Rags, riches and women workers: export-oriented garment manufacturing in Bangladesh. In: Carr M (ed) Chains of fortune: linking women producers and workers with global markets. Commonwealth Secretariat, London, pp. 133–164

Kane G (2015) India Country Report. An Overview of the Garment Industry. Amsterdam: Clean Clothes Campaign. www.cleanclothes.org/resources/publications/factsheets/

Klöpffer W (2008) Life cycle sustainability assessment of products. Int J Life Cycle Assess 13(2):89–95

Lambert, PJ (2001) The distribution and redistribution of income. Manchester University Press

Layard R, Nickell S, Mayraz G (2008) The marginal utility of income. J Public Econ 92:1846–1857

Macombe C, Leskinen P, Feschet P, Antikainen R (2013) Social life cycle assessment of biodiesel production at three levels: a literature review and development needs. J Clean Prod 52:205–216

Moavenzadeh J, Doherty S, Philip R, Geiger T, Gottfredson M, Mattios G, Willink BT, Correa A, Hoekman B, Jackson S, Ferrantino M, Tsigas M (2013) Enabling trade. Valuing growth opportunities. World Economic Forum, Geneva

Psacharopoulos G (1994) Returns to investment in education: a global update. World Dev 22(9):1325–1343

Reitinger C, Dumke M, Barosevcic M, Hillerbrand R (2011) A conceptual framework for impact assessment within SLCA. Int J Life Cycle Assess 16(4):380–388

Tukker A, de Koning A, Wood R, Hawkins T, Lutter S, Acosta J, Rueda Cantuche JM, Bouwmeester M, Oosterhaven J, Drosdowski T, Kuenen J (2013) EXIOPOL – development and illustrative analyses of a detailed global MR EE SUT/IOT. Econ Syst Res 25(1):50–70

Weidema BP (2006a) The integration of economic and social aspects in life cycle impact assessment. Int J Life Cycle Assess 11(1):89–96

Weidema, BP (2006b) Social impact categories, indicators, characterisation, and damage modelling. Presentation for the 29th Swiss LCA Discussion Forum 2006.07.15

Weidema BP (2009) Using the budget constraint to monetarise impact assessment results. Ecol Econ 68(6):1591–1598

Weidema, BP (2015) The social footprint – A practical approach to comprehensive and consistent social LCA. Presentation to the SETAC 25th Annual meeting, Barcelona, 2015.05.3–7

Worldbank (2015) Data. GDP (current LCU). GDP per capita (current US$). Labour force, total. Population, total. Population, ages 0–14 (% of total). Unemployment, total (% of total labor force). http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CN/, NY.GDP.PCAP.CD/, SL.TLF.TOTL.IN/, SP.POP.TOTL/, SP.POP.0014.TO.ZS/, and SL.UEM.TOTL.ZS/ (accessed 2015–07-29)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Miguel Brandão for constructive sparring during the development of the arguments presented in this article and for nudging us to submit it to this special issue. The ideas were originally presented orally to the 2015 SETAC-Europe Annual meeting in Barcelona (Weidema 2015). We are also grateful for detailed and helpful comments from three anonymous reviewers of the originally submitted manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Catherine Macombe

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Weidema, B.P. The social footprint—a practical approach to comprehensive and consistent social LCA. Int J Life Cycle Assess 23, 700–709 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-016-1172-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-016-1172-z