Abstract

This paper considers the extent to which the notion of truthmaking can play a substantive role in defining physicalism. While a truthmaking-based approach to physicalism is prima facie attractive, there is some reason to doubt that truthmaking can do much work when it comes to understanding physicalism, and perhaps austere metaphysical frameworks in general. First, despite promising to dispense with higher-level properties and states, truthmaking appears to make little progress on issues concerning higher-level items and how they are related to how things are physically. Second, it seems that truthmaking-based approaches to physicalism will have a difficult time addressing the status of truthmaking itself without, in effect, appealing to the resources of alternative ways of conceptualizing physicalism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

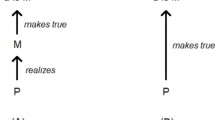

For approaches to physicalism that appeal to relations like supervenience, realization, and constitution, see Boyd (1980), Chalmers (1996), Howell (2009), Jackson (1998), Levine (2001), Loewer (2001), Melnyk (2003), Pereboom (2011), Putnam (1967), Shoemaker (2007), Tye (1995), and Wilson (2005). The label “nonreductive” is imperfect, due to different uses of “reduction” as well as disagreement about the consequences of understanding physicalism in terms of these relations. Regarding the first issue, I am using “nonreductive” in a broad sense to cover any approach that countenances entities or properties distinct from strictly physical entities and properties. An approach may be nonreductive in this sense while being reductive in other senses: for example, it is consistent with an approach accepting the reductive explainability of higher-level truths, if reductive explanation does not require metaphysical reduction. As an example of the second issue, while Shoemaker (2007) puts forward an account of physical realization as a way of articulating nonreductive physicalism, it is a matter of dispute whether the account succeeds in its nonreductive aspirations (see Kim 2010; Morris 2011; Ney 2010 for discussion). Similarly, it is a matter of dispute whether functionalism and a thesis of functional realization leads to metaphysical reduction (see Kim 2005; Block 2015 for discussion; Melnyk 2003 argues that functional realization leads to a kind of explanatory reduction). In some cases, relations like supervenience and realization are appealed to as something like premises in an argument for a reductionist picture. One might read Kim’s (2005) use functional realization in this way, as well as his recent defense of supervenience-based understandings of physicalism (see Kim 2011; for discussion, see Morris 2014); similarly, while Chalmers (1996) and Jackson (1998) formulate physicalism in terms of supervenience, they go on to argue that the supervenience thesis at issue requires the a priori deducibility of all truths about the world from a description of the world in the language of physics, which appears to at least support a kind of explanatory reduction (see Sect. 2.3 for related discussion).

For concerns along these lines, and the suggestion that they motivate a “one-level” approach to physicalism (and perhaps any comprehensive metaphysical outlook), see Heil (2003) and Kim (1998, 2005); for discussion focused on attempts to understand physicalism in terms of supervenience, see Horgan (1993) and Melnyk (2003). Melnyk (2003) argues that realization supports a kind of explanatory reduction; however, he does not infer from this a “flat” metaphysics (see fn. 3 for related discussion).

Sharpe (unpublished ms) does explicitly develop a truthmaking-based approach to physicalism, which he calls “truthmaking physicalism”. While Heil does not develop a truthmaking-based view of physicalism, much of what he says is suggestive of this. For example, he develops (2003, Chapters 2–7) a truthmaking-based approach to metaphysics as a response to what is essentially the nonreductive physicalist commitment to “levels of reality”. Further, he appears to hold (2012, Chapter 8) that the truthmakers for ordinary and special science discourse are ultimately to be discovered by physics.

Truthmaking theory is itself an area of dispute, and those interested in truthmaking have debated the nature of truthbearers, truthmakers, and the truthmaking relation, whether it ought to be held that all truths have truthmakers, and so on. For discussion, see the papers in Beebee and Dodd (2005) and Lowe and Rami (2009). My aim is to remain as neutral as possible on these issues. However, some of my discussions will work from one or another account of truthmaking.

See Merricks (2007).

See Schulte (2014). Admittedly, given the disputes that have occupied truthmaker theorists about the nature of truthbearers, truthmaking, and truthmakers (see fn.7), it is likely that not all will regard this as trivial.

This is essentially what Heil (2003) labels “Principle (Φ)”, which he takes to be a core component of the linguistic approach to metaphysics that he rejects.

Schulte’s “problem of higher-level entities” is similar to, though distinct from, the concerns that I will raise about truthmaking physicalism. Schulte (2014) is primarily interested in the extent to which various accounts of truthmaking have the consequence that items not needed as truthmakers are “ontological free lunches”. This is relevant to truthmaking physicalism, since the truthmaking physicalist should prefer an account of truthmaking under which items not needed as truthmakers are “ontological free lunches”. Nonetheless, Schulte is not interested specifically in the extent to which truthmaking can be used to understand physicalism. I discuss Schulte’s proposal for understanding truthmaking in Sect. 2.3.

See the references in fn. 6. While Heil might be read in this way, it is not entirely clear to me where he stands on these issues. A broadly reductionist position about things like tomatoes and properties like redness is suggested by his rejection, in From an Ontological Point of View, of any levels-based metaphysics. In more recent work, however, he seems more amenable to using truthmaking to draw a distinction between the fundamental and the derivative, with physics given the role of describing how the world is fundamentally; see, for example, Heil (2012), Chapter 8. I discuss a position like this in Sect. 2.2.

Below I discuss the related suggestion that when properly understood, truthmaking physicalism should be understood as a kind of eliminativism about higher-level items; see Sect. 2.2.

See Schulte (2014) for discussion. For views of truthmaking along these lines, see Armstrong (1997, 2004). For related views, see Bigelow (1988) and Lewis (2001). Schaffer (2008) attributes this kind of view to Cameron; however, Cameron (2008, 2010) is not especially forthcoming about the nature of truthmaking.

For example, while rejecting simple necessitation-based accounts of truthmaking, Merricks (2007) essentially adds to them an aboutness condition on the truthbearer, that it must be about its truthmaker. Likewise, various authors have proposed understanding truthmaking in terms of an “in virtue of” or “grounding” notion, which appears to be understood as entailing, though not entailed by, the thesis that truthmakers necessitate the truth of what they make true (see Rodriguez-Pereyra 2005; Schaffer 2008; for a related suggestion, see Lowe 2009).

Schaffer (2008) argues that truthmaking cannot provide an alternative to a Quinean approach to ontology on the grounds that a truthmaking-based theory will take certain quantifier-based commitments, those that assert the existence of a truthmaker, to be ontologically committal. My interest, however, is not with the extent to which truthmaking can provide a distinctive measure of ontological commitment. For even if “ontological commitment” is understood in truthmaker-theoretic terms, it can still be asked how those items that exist but are not ontological commitments are related to those that are ontological commitments.

This appears to be the view in Sharpe (unpublished ms).

The concern here is not that there cannot be a physicalist account of truthmaking. For example, if supervenience were sufficient for “physicalistic acceptability”, one could claim that truthmaking is unproblematic on the grounds that truthmaking supervenes on physical reality. Nor is the concern that it is impossible to articulate truthmaking in other terms—for example, in terms of an “in virtue of” or “grounding” notion (see fn. 18). Rather, the concern is specifically that truthmaking will not play a role in explaining the place of truthmaking itself in the physical world.

Two points are worth noting. First, it should be emphasized that the concerns here arise specifically for the truthmaking-based approach to physicalism, and (perhaps unlike the concerns raised in Sect. 2) do not appear to threaten the general use of truthmaking in austere metaphysical pictures. This is significant, in part, because certain objections to truthmaking-based theories of fundamentality, such as those developed in Sider (2011), can perhaps be met by taking truthmaking to be fundamental (see Fisher 2015). However, a strategy like this is unavailable to the truthmaking physicalist: physicalism places constraints on the fundamental metaphysics, and plausibly these constraints exclude fundamental truthmaking. Second, the present line of thought targets views that take truthmaking to be a relation between language and world, and has little force against views that take truthmaking to be an operator on sentences or representations (Melia 2005; Schneider 2006). While addressing the issues that these views raise for truthmaking physicalism would require a lengthy discussion, the following points are salient. First, those who have utilized truthmaking to understand austere metaphysical pictures have emphasized the role of truthmaking as a relation between truthbearers and the world, and not as a sentential operator. Second, they have supposed that truthmaking can play a role in delineating metaphysical issues from linguistic ones. This may prove untenable if “making true” is construed as a sentential operator. Third, while understanding “makes true” as a sentential operator may avoid the concerns developed in Sect. 3, such proposals do not straightforwardly avoid those advanced in Sect. 2.

References

Armstrong D (1997) A world of states of affairs. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Armstrong D (2004) Truth and truthmakers. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Beebee H, Dodd J (eds) (2005) Truth-makers: the contemporary debate. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Bigelow J (1988) The reality of numbers: a physicalist’s philosophy of mathematics. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Block N (2015) The Canberra plan neglects ground. In: Horgan T, Sabatés M, Sosa D (eds) Qualia and mental causation in a physical world. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Block N, Stalnaker R (1999) Conceptual analysis, dualism, and the explanatory gap. Philos Rev 108:1–46

Boyd R (1980) Materialism without reductionism: what physicalism does not entail. In: Block N (ed) Readings in philosophy of psychology, vol 1. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Byrne A (1999) Cosmic hermeneutics. Philos Perspect 13:347–383

Cameron R (2008) Truthmakers and ontological commitment: or how to deal with complex objects and mathematical ontology without getting into trouble. Philos Stud 140:1–18

Cameron R (2010) How to have a radically minimal ontology. Philos Stud 151:249–264

Cameron R, Barnes E (2007) A critical study of John Heil’s from an ontological point of view. SWIF Philos Mind Rev 6:22–30

Chalmers D (1996) The conscious mind. In search of a fundamental theory. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Chalmers D, Jackson F (2001) Conceptual analysis and reductive explanation. Philos Rev 110:315–360

Fisher A (2015) Truthmaking and fundamentality. Pac Philos Q. doi:10.1111/papq.12082

Fodor J (1974) Special sciences (or: the disunity of science as a working hypothesis). Synthese 28:97–115

Heil J (2003) From an ontological point of view. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Heil J (2012) The universe as we find it. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Horgan T (1993) From supervenience to superdupervenience: meeting the demands of a material world. Mind 102:555–586

Howell R (2009) Emergentism and supervenience physicalism. Australas J Philos 87:83–98

Jackson F (1998) From metaphysics to ethics: a defense of conceptual analysis. Clarendon Press, New York

Kim J (1998) Mind in a physical world. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Kim J (2002) The layered model: metaphysical considerations. Philos Explor 5:2–20

Kim J (2005) Physicalism, or something near enough. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Kim J (2010) Thoughts on Sydney Shoemaker’s physical realization. Philos Stud 148:101–112

Kim J (2011) From naturalism to physicalism: supervenience redux. Proc Am Philos Assoc 85:109–134

Levine J (2001) Purple haze. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Lewis D (2001) Truthmaking and difference-making. Nous 35:602–615

Loewer B (2001) From physics to physicalism. In: Gillett C, Loewer B (eds) Physicalism and its discontents. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Lowe EJ (2009) An essentialist approach to truthmaking. In: Lowe EJ, Rami A (eds) Truth and truth-making. Acumen, Stocksfield

Lowe EJ, Rami A (eds) (2009) Truth and Truth-making. Acumen, Stocksfield

Melia J (2005) Truthmaking without truthmakers. In: Beebee H, Dodd J (eds) Truth-makers: the contemporary debate. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Melnyk A (2003) A physicalist manifesto. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Merricks T (2007) Truth and ontology. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Morris K (2011) Subset realization and physical identification. Can J Philos 41:317–335

Morris K (2014) Causal closure, causal exclusion, and supervenience physicalism. Pac Philos Q 95:72–86

Ney A (2010) Convergence on the problem of mental causation: Shoemaker’s strategy for (nonreductive?) physicalists. Philos Issues 20:438–445

Pereboom D (2011) Consciousness and the prospects of physicalism. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Polger T (2013) Physicalism and moorean supervenience. Anal Philos 54:72–92

Putnam H (1967) Psychological predicates. In: Capitan WH, Merrill DD (eds) Art, mind and religion. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh

Rodriguez-Pereyra G (2005) Why truthmakers. In: Beebee H, Dodd J (eds) Truth-makers: the contemporary debate. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Schaffer J (2008) Truthmaker commitments. Philos Stud 141:7–19

Schneider B (2006) Truth-making without truth-makers. Synthese 152:21–46

Schulte P (2014) Can truthmaker theorists claim ontological free lunches? Eur J Philos 22:249–268

Sharpe K (Unpublished Manuscript) Psychophysical reduction without property identity

Shoemaker S (2007) Physical realization. Oxford University Press, New York

Sider T (2011) Writing the book of the world. Oxford University Press, New York

Tye M (1995) Ten problems of consciousness. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Wilson J (2005) Supervenience-based formulations of physicalism. Noûs 39:426–459

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Morris, K. Physicalism, Truthmaking, and Levels of Reality: Prospects and Problems. Topoi 37, 473–482 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-016-9379-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-016-9379-y