Abstract

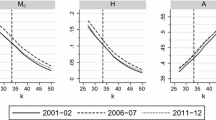

Although the multidimensional approach to poverty is a common-sense idea, there have been numerous debates on what kind of dimensions can be included in the concept. As one way of addressing the issue, I introduce a dimension of ‘time’, which could help us to select more relevant dimensions by displaying the changes in their influence on the multidimensional poverty over a period of time. After the thirteen waves of British Household Panel Survey data, 1996–2008, are analyzed for a multidimensional poverty based on the Capability approach, I find out that most of the dimensions that have mentioned in previous research demonstrate a consistent influence on poverty over the period, which implies that existing literature on multidimensional poverty has been on the right path. Also, it turns out that the dimensions of ‘health’ and ‘social capital’ are getting more weights in measuring the multidimensional poverty, while ‘economic resources’ dimension is still the most influential factor for the construct. The findings seem to suggest that the multidimensional approach as it stands is quite relevant, though an agreeable list of dimensions of poverty still requires far more intellectual endeavor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It is certain that the negative impressions on the result of the “War” also have a lot to do with the implementation part of a policy process, which were convincingly argued in Pressman and Wildavsky (1979)’s ground–breaking research.

It is certain that it also depends heavily on regional differences. Recently, the U.S. Census Bureau begins to produce the Supplemental Poverty Measurement series, and one of the main arguments for it is that it is indispensable to take the geographic variation in the cost of living into account when we measure poverty (Meyer and Sullivan 2012).

Tomlinson et al. (2008), however, argue that even the initial students of poverty measurement already realized the need to take account of social conditions. Also, they find that Adam Smith already considered “shame and stigma” as an inherent components of poverty.

It is also worthwhile to note that S. Anand and Sen (1997) argues that the tendency to concentrate on other variables than income, such as, the inability to take part in the life of the community, is especially strong in the more affluent countries.

It has to be noted that the existence of one operational definition does not necessarily mean there should be one composite index for social exclusion. Marlier and Atkinson (2010) even advocate that the key dimensions of social exclusion should not be aggregated into one index “not to conceal dissensions in a ‘scientific’ model” (Erikson 1974).

It has three main “pillars”, which can be outlined as “Promote the effective exercise of fundamental rights”, “Promote an integrated approach and action”, and “Promote participation and partnership”(Demeyer & Farrell 2005).

Sen (1992) argues that to have a choice to go without food, i.e., for religious reason, shows one has more freedom than the other one who only has a choice to eat (no matter whether it is possible), for example, people in the sub-Saharan Africa who usually cannot but live in a deprivation of food.

On the contrary, Nussbaum (2003) argues enthusiastically for a list of central capabilities as a guideline.

“Lack of functionings” does not imply a binary distinction. With some difficulty in designing measurement system, it is entirely possible to make a measurement that can distinguish the extent of it.

Measuring these conditions, the author strongly recommends using both objective and subjective indicators. While objective indicators refer to the observation of factual conditions, subjective indicators stand for “measurement of attitudes” (Allardt 1993). For example, the ratio of students to teachers can be an objective indicator for an educational environment, whereas subjective indicators can be obtained by asking students’ opinion about the educational environment.

“Existential” categories indicate four aspects of human existence: being, having, doing, and interacting, each of which corresponds to personal or collective attribute, institutional context, actions, and locations and milieus (as times and spaces), respectively. On the other hand, “axiological” categories denote nine dimensions of human needs.

Specific meanings of these dimensions are not elaborated by the author, but indicators of the dimensions are fully provided.

Robeyns (2000) reviews twelve researches adopting the capability approach, and all of them regard health as an important functioning.

Tomer (2002) puts it in this way, “It is not about how much food one consumes; it is about eating tasty food and being well-nourished.”

These phrases indicate that there is still a room for inevitable arbitrariness in terms of choosing specific indicators, because the concept of “modern American society” or “every-day life activities” implies cultural or relative aspects of poverty.

Foster and Shorrocks (1988) point that arbitrary decisions also exist in traditional poverty measurements. They identify two main sources of arbitrariness: (1) the precise functional form adopted to aggregate influences the results eventually obtained, and (2) how to set a poverty line. See also Haughton (2009); Ringen (1988).

For more detailed discussion on the arbitrariness in multidimensional poverty measurement, see Qizilbash (2004).

Since the multiple imputation method generally stands on the assumption of missing at random (MAR), this should not be understood as concluding that missingness is irrelevant. However, as van Buuren (2012) shows, the multiple imputation method is “remarkably robust against not missing at random (NMAR)” situation. Besides, I utilize the fully conditional specification (FCS) which are known to provide multiple imputation results minimal bias and maximal efficiency (Meng 1994; Collins et al. 2001). Also, the examination of ‘relative bias’—according to Graham (2012), it can be assessed by looking into the residual covariance matrix in SEM context—displays that the bias introduced by missingness is not great.

There are two points involving measurement error. The first is that no single variable represents appropriately a functioning, and the second is that a subjective evaluation often implies the "anchoring" problem, different connotations due to a reference group (Kuklys 2005; Kuklys and Robeyns 2004).

Kline (2011) categorizes the indices other than Chi square statistic as “approximate fit indexes” because these statistics do not take sampling error into account and they can vary across samples for a same model. He further points that the thresholds for the indexes would not be justified because models with an acceptable model fit can still account for a part of model very poorly.

As a matter of fact, Brown (2006) points that the transformation would not change the explanatory power of the original solution.

Meyer and Sullivan (2012) delve into the diverse measures of poverty to understand how different people are categorized as poor by those measurements. They find that a ‘health spending’ indicator, which is the proxy for health status in the newly-developed “Supplemental Poverty Measurement (SPM)” in the U.S., has a rather complex relationship with health status. It does not necessarily mean that health spending is not a reliable observation, but it does suggest that we need to consider health status itself whenever it is available.

Anand et al. (2005) argue that it is better for policymakers to try to enhance the choice set available to people rather than to point out what people choose to do accurately.

This point is epitomized by Sen (1979a)’s Cambridge University lecture title “Equality of What?” If measuring poverty is an evaluation of a situation, we have an agreement on neither what kind of situation we should look into nor what criteria we should be based on. Sen calls this “a valuation problem”.

References

Addison, T., Hulme, D., & Kanbur, R. (2009). Poverty dynamics: Interdisciplinary perspectives. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Alkire, S. (2002). Dimensions of human development. World Development, 30(2), 181–205.

Alkire, S. (2008). Choosing dimensions: The capability approach and multidimensional poverty. In N. Kakwani & J. Silber (Eds.), The many dimensions of poverty. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Alkire, S., & Black, R. (1997). A practical reasoning theory of development ethics: Furthering the capabilities approach. Journal of International Development, 9(2), 263–279.

Allardt, E. (1993). Having, loving, being: An alternative to the swedish model of welfare research. In M. C. Nussbaum & A. K. Sen (Eds.), The quality of life. New York: Oxford University Press.

Anand, P., Hunter, G., Carter, I., Dowding, K., Guala, F., & Van Hees, M. (2009). The development of capability indicators. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 10(1), 125–152.

Anand, P., Hunter, G., & Smith, R. (2005). Capabilities and well-being: Evidence based on the Sen-Nussbaum approach to welfare. Social Indicators Research, 74(1), 9–55.

Anand, P., Krishnakumar, J., & Tran, N. B. (2010). Measuring welfare: Latent variable models for happiness and capabilities in the presence of unobservable heterogeneity. Journal of Public Economics, In Press, Accepted Manuscript.

Anand, S., & Sen, A. K. (1997). Concepts of human development and poverty: A multidimensional perspective. Human Development Papers, 1–19.

Antolin, P., Dang, T. T., & Oxley, H. (2000). Poverty Dynamics in Six OECD Countries (OECD Economic Studies No. 02550822). OECD Publications and Information Centre.

Atkinson, A. B. (1999). The contributions of Amartya Sen to welfare economics. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 101(2), 173–190.

Atkinson, A. B. (2003). Multidimensional deprivation: Contrasting social welfare and counting approaches. Journal of Economic Inequality, 1(1), 51–65.

Atkinson, A. B., Marlier, E., & Nolan, B. (2004). Indicators and targets for social inclusion in the European Union. Journal of Common Market Studies, 42(1), 47–75.

Ballon, P., & Krishnakumar, J. (2010). Measuring Multidimensional Poverty: A Model-Based Index of Capability Deprivation (Unpublished Work). Geneva.

Bane, M. J., & Ellwood, D. T. (1986). Slipping into and out of poverty: The dynamics of spells. Journal of Human Resources, 21(1), 1–23.

Basu, K. (1987). Achievements, capabilities and the concept of well-being. Social Choice and Welfare, 4(1), 69–76.

Bauman, K. J. (2003). Extended measures of well-being: living conditions in the United States, 1998 [sssssGovernment Document]. USA: U.S Census Bureau.

Benner, C., & Pastor, M. (2012). Just growth: Inclusion and prosperity in America’s metropolitan regions. New York, NY: Routledge.

Bérenger, V., & Verdier-Chouchane, A. (2007). Multidimensional measures of well-being: Standard of living and quality of life across countries. World Development, 35(7), 1259–1276.

Betti, G., Cheli, B., Lemmi, A., & Verma, V. (2005). The fuzzy approach to multidimensional poverty: The case of Italy in the 90’s. [Conference Paper] UNDP. August 29–31, 2005.

Betti, G., & Verma, V. (1998). Measuring the Degree of Poverty in a Dynamic and Comparative Context: A Multi-Dimensional Approach using Fuzzy Set Theory (Electronic Article No. 22). Universita di Siena, Dipartimento di Metodi Quantitativi.

Blank, R. M. (2008). Presidential address: How to improve poverty measurement in the United States. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 27(2), 233–254.

Boarini, R., & d’Ercole, M. M. (2006). Measures of Material Deprivation in OECD Countries (Generic No. 37). OECD.

Booth, C. (1892). Life and labour of the people of London. London, U.K.: Macmillan.

Booysen, F. (2002). An overview and evaluation of composite indices of development. Social Indicators Research, 59(2), 115–151.

Bossert, W., Chakravarty, R., Satya, & D’Ambrosio, C. (2009). Multidimensional poverty and material deprivation [Electronic Article]. Society for the Study of Economic Inequality (ECINEQ).

Bossert, W., D’Ambrosio, C., & Peragine, V. (2007). Deprivation and social exclusion. Economica, 74(296), 777–803.

Bourguignon, F., & Chakravarty, S. R. (2003). The measurement of multidimensional poverty. Journal of Economic Inequality, 1(1), 25–49.

Bradshaw, J. (2000). Prospects for poverty in britain in the first twenty-five years of the next century. Sociology-the Journal of the British Sociological Association, 34(1), 53–70.

Bradshaw, J., & Finch, N. (2003). Overlaps in dimensions of poverty. Journal of Social Policy, 32(4), 13.

Brady, D. (2003). Rethinking the sociological measurement of poverty. Social Forces, 81(3), 36.

Brandolini, A., & D’Alessio, G. (1998). Measuring well-being in the functioning space [Unpublished Work]. Rome, Banca d’Italia.

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Carr-Hill, R. (1986). An approach to monitoring social welfare. In P. Nolan & S. Paine (Eds.), Rethinking socialist economics: A new agenda for Britain. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Cellini, S. R., McKernan, S.-M., & Ratcliffe, C. (2008). The dynamics of poverty in the United States: A review of data, methods, and findings. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 27(3), 577–605.

Chiappero-Martinetti, E. (2000). A multidimensional assessment of well-being based on Sen’s functioning approach. Rivista Internazionale di Scienze Sociali, 2, 207–239.

Citro, C. F., & Michael, R. T. (1995). Measuring poverty: A new approach. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Clark, D. A. (2003). Concepts and perceptions of human well-being: Some evidence from South Africa. Oxford Development Studies, 31(2), 173.

Clark, D. A., & Qizilbash, M. (2008). Core poverty, vagueness and adaptation: A new methodology and some results for South Africa. Journal of Development Studies, 44(4), 519–544.

Collins, L. M., Schafer, J. L., & Kam, C. M. (2001). A comparison of inclusive and restrictive strategies in modern missing data procedures. Psychological Methods, 6(3), 330–351.

Costa, M. (2002). A multidimensional approach to the measurement of poverty (IRISS Working Paper Series). IRISS at CEPS/INSTEAD. Retrieved December from http://ideas.repec.org/p/irs/iriswp/2002-05.htmlsss

Couch, K. A., & Pirog, M. A. (2010). Poverty measurement in the U.S., Europe, and developing countries. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 29(2), 217–226.

Cummins, R. A. (1996). The domains of life satisfaction: An attempt to order chaos. Social Indicators Research, 38(3), 303–328.

Dagum, C., & Costa, M. (2004). Analysis and measurement of poverty: Univariate and multivariate approaches and their policy implications: A case study: Italy. In C. Dagum & G. Ferrari (Eds.), Household Behaviour. Equivalence Scales, Welfare and Poverty Heidelberg, Germany: Physica-Verlag.

Danziger, S., & Haveman, R. H. (2001). Understanding Poverty. Cambridge, MA: Russell Sage Foundation; Harvard University Press.

Danziger, S., & Weinberg, D. H. (1986). Fighting poverty: What works and what doesn’t. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Demeyer, B., & Farrell, F. (2005). Indicators of social quality and the anti-poverty strategies. European Journal of Social Quality, 5, 1–2.

Desai, M. (1991). Human development: concepts and measurement. European Economic Review, 35(2–3), 350–357.

Desai, M., & Shah, A. (1988). An econometric approach to the measurement of poverty. Oxford Economic Papers, 40(3), 505–522.

Deutsch, J., & Silber, J. (2005). Measuring multidimensional poverty: An empirical comparison of various approaches. Review of Income and Wealth, 51(1), 145–174.

Dewilde, C. (2004). The multidimensional measurement of poverty in Belgium and Britain: A categorical approach. Social Indicators Research, 68(3), 331–369.

Doyal, L., & Gough, I. (1991). A theory of human need. New York: Guilford Press.

Duclos, J. Y., Sahn, D. E., & Younger, S. D. (2006). Robust multidimensional poverty comparisons. The Economic Journal, 116(514), 943–968.

Duncan, G. J., Gustafsson, B., Hauser, R., Schmauss, G., Messinger, H., Muffels, R., & Ray, J.-C. (1993). Poverty dynamics in eight countries. Journal of Population Economics, 6(3), 215–234.

Erikson, R. (1974). Welfare as a planning goal. Acta Sociologica, 17, 273–288.

Esposito, L., & Chiappero-Martinetti, E. (2008). Multidimensional Poverty Measurement: Restricted and Unrestricted Hierarchy among Poverty Dimensions [Unpublished Work]. Oxford. Retrieved from www.ophi.org.uk

Federman, M., & Garner, T. I. (1996). What does it mean to be poor in America? Monthly Labor Review, 119(5), 3.

Foster, J. E. (1984). On economic poverty: A survey of aggregate measures. Advances in Econometrics, 3, 215–252.

Foster, J. E., & Shorrocks, A. F. (1988). Poverty orderings and welfare dominance. Social Choice and Welfare, 5(2), 179–198.

Fukuda-Parr, S. (2003). The human development paradigm: Operationalizing Sen’s ideas on capabilities. Feminist Economics, 9(2/3), 301.

Graham, J. W. (2012). Missing data: Analysis and design. New York, NY: Springer.

Grusky, D. B., & Kanbur, R. (2006). Introduction: The conceptual foundations of poverty and inequality measurement. In D. B. Grusky & R. Kanbur (Eds.), Poverty and Inequality. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Hacourt, G. (2003). Poverty indicators: Starting from the experience of people living in poverty (Report). European Anti-Poverty Network.

Haughton, J. H. (2009). Handbook on poverty and inequality. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Hayati, D., Karami, E., & Slee, B. (2006). Combining qualitative and quantitative methods in the measurement of rural poverty: The case of Iran. Social Indicators Research, 75(3), 361–394.

Himmelfarb, G. (1991). Poverty and compassion: The Moral Imagination of the Late Victorians. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Hulme, D., & McKay, A. (2007). Identifying and measuring chronic poverty: Beyond monetary measures? In N. Kakwani & J. Silber (Eds.), The Many Dimensions of Poverty. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jäntti, M. (2009). Mobility in the United States in comparative perspective. Focus, 26(2), 38–42.

Jenkins, S. P., & Micklewright, J. (2007). Inequality and poverty re-examined. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press.

Kahneman, D., Krueger, A. B., Schkade, D., Schwarz, N., & Stone, A. (2004). Toward national well-being accounts. American Economic Review, 94(2), 429–434.

Kakwani, N., & Silber, J. (2007). The many dimensions of poverty. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kangas, O., & Ritakallio, V.-M. (1998). Different methods—different results? approaches to multidimensional poverty. In H.-J. Andress (Ed.), Empirical poverty research in a comparative perspective (pp. 167–203). Hants, UK: Ashgate.

Kaplan, D. (2000). Structural equation modeling: foundations and extensions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Kim, S.-G. (2014). Fuzzy multidimensional poverty measurement: An analysis of statistical behaviors. Social Indicators Research, 120(3), 635–667.

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Kuklys, W. (2005). Amartya Sen’s capability approach: theoretical insights and empirical applications. New York: Springer.

Kuklys, W., & Robeyns, I. (2004). Sen’s capability approach to welfare economics (Report). Cambridge University.

Lelli, S. (2001). Factor analysis vs. Fuzzy sets theory: Assessing the influence of different techniques on Sen’s functioning approach (Report). K. U. Leuven, DPS.

Lichter, D. T., & Crowley, M. L. (2002). Poverty in America: Beyond Welfare Reform (Vol. 57) (Generic No. 2). The Population Reference Bureau.

Maasoumi, E., & Lugo, M. A. (2008). The information basis of multivariate poverty assessments. In N. Kakwani & J. Silber (Eds.), Quantitative approaches to multidimensional poverty measurement. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Marlier, E., & Atkinson, A. B. (2010). Indicators of poverty and social exclusion in a global context. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 29(2), 285–304.

Max-Neef, M. A. (1993). Human scale development: Conception, Application and further reflections. New York: The Apex Press.

Meng, X.-L. (1994). Multiple imputation with uncongenial sources of input (with Discussion). Statistical Science, 9(4), 538–573.

Meyer, B. D., & Sullivan, J. X. (2012). Identifying the disadvantaged: official poverty, consumption poverty, and the new supplemental poverty measure. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26(3), 111–136.

Millar, J. (2003). Gender, poverty and social exclusion. Social Policy and Society, 2(3), 181–188.

Morduch, J. (1994). Poverty and vulnerability. American Economic Review, 84(2), 221–225.

Muffels, R. (1993). Deprivation standards and style of living indices. In J. Berghman & B. Cantillon (Eds.), The European face of social security: Essays in honour of Herman Deleeck. Avebury: Brookfield, VT.

Muffels, R., Berghman, J., & Dirven, H.-J. (1992). A multi-method approach to monitor the evolution of poverty. Journal of European Social Policy, 2(3), 193–213.

Mussard, S., & Pi Alperin María, N. (2005). Multidimensional decomposition of poverty: A Fuzzy Set approach (Report). Groupe de Recherche en Économie et Développement International. Retrieved from http://ideas.repec.org/p/shr/wpaper/05-08.html

Narayan, D., Patel, R., Schafft, K., Rademacher, A., & Koch-Schulte, S. (2000). Can anyone hear us?: Voices from 47 countries. New York: Oxford University Press for the World Bank.

Nolan, B., & Whelan, C. T. (2010). Using non-monetary deprivation indicators to analyze poverty and social exclusion: Lessons from Europe? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 29(2), 305–325.

Nussbaum, M. C. (2000). Women and human development: The capabilities approach. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Nussbaum, M. C. (2003). Capabilities as fundamental entitlements: Sen and social justice. Feminist Economics, 9(2/3), 33.

Orshansky, M. (1965). Counting the poor: Another look at the poverty profile. Social Security Bulletin, 28(1), 3–29.

Øyen, E. (1996). Poverty Research Rethought. In E. Øyen, S. M. Miller, & S. A. Samad (Eds.), Poverty: a global review: Handbook on international poverty research (pp. 3–17). Boston, MA: Scandinavian University Press.

Pastor, M., & Benner, C. (2008). Been down so long: Week market cities and regional equity. In R. McGahey & J. Vey (Eds.), Restoring Prosperity in Older Industrial Areas. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Pressman, J., & Wildavsky, A. B. (1979). Implementation: How great expectations in Washington are dashed in Oakland. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Qizilbash, M. (1996). Capabilities, well-being and human development: A Survey. Journal of Development Studies, 33(2), 143.

Qizilbash, M. (1997). Pluralism and well-being indices. World Development, 25(12), 2009–2026.

Qizilbash, M. (2004). On the Arbitrariness and robustness of multidimensional poverty rankings. Journal of Human Development, 5(3), 355–375.

Rank, M. R., & Hirschl, T. A. (2001). The occurrence of poverty across the life cycle: Evidence from the PSID. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 20(4), 737–755.

Ringen, S. (1988). Direct and indirect measures of poverty. Journal of Social Policy, 17(03), 351–365.

Ringen, S. (1995). Well-being, measurement, and preferences. Acta Sociologica, 38(1), 3–15.

Robeyns, I. (2000). An Unworkable idea or a promising alternative? Sen’s capability approach re-examined [Unpublished Work]. Leuven, Germany.

Robeyns, I. (2003). Sen’s capability approach and gender inequality: Selecting relevant capabilities. Feminist Economics, 9(2/3), 61.

Robeyns, I. (2006). The Capability Approach in Practice. Journal of Political Philosophy, 14(3), 351–376.

Rowntree, B. S. (1901). Poverty: A study of town life. London, UK: Macmillian.

Schmid, J., & Leiman, J. M. (1957). The development of hierarchical factor solutions. Psychometrika, 22, 53–61.

Seccombe, K. (2000). Families in poverty in the 1990s: Trends, causes, consequences, and lessons learned. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 1094–1113.

Seers, D. (1969). The meaning of development. International Development Review, 11(2), 2–6.

Seidl, C. (1988). Poverty Measurement: A Survey. In D. Bös, M. Rose, & C. Seidl (Eds.), Welfare and efficiency in public economics (pp. 71–147). New York: Springer-Verlag.

Sen, A. K. (1979a). Equality of what? [Electronic Article]. April 17, 2010.

Sen, A. K. (1979b). Issues in the measurement of poverty. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 81(2), 285–307.

Sen, A. K. (1979c). Personal utilities and public judgments: Or what’s wrong with welfare economics. The Economic Journal, 89(355), 537–558.

Sen, A. K. (1985a). Commodities and capabilities. New York: Elsevier Science.

Sen, A. K. (1985b). A Sociological approach to the measurement of poverty: A reply to professor peter townsend. Oxford Economic Papers, 37(4), 669–676.

Sen, A. K. (1985c). The Standard of Living [Electronic Article]. University of Cambridge.

Sen, A. K. (1992). Inequality reexamined. Cambridge: Russell Sage Foundation; Harvard University Press.

Sen, A. K. (1993). Capability and well-being. In M. C. Nussbaum & A. K. Sen (Eds.), The Quality of Life. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sen, A. K. (1997). On economic inequality. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Sen, A. K. (2000). A decade of human development. Journal of Human Development, 1(1), 17–23.

Sen, A. K. (2004a). Capabilities, lists, and public reason: Continuing the conversation. Feminist Economics, 10(3), 77–80.

Sen, A. K. (2004b). Elements of a theory of human rights. Philosophy and Public Affairs, 32(4), 315–356.

Smeeding, T. (2006). Poor people in rich nations: The United States in comparative perspective. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(1), 69–90.

Stevens, A. H. (1994). The dynamics of poverty spells: Updating Bane and Ellwood. The American Economic Review, 84(2), 34–37.

Stevens, A. H. (1999). Climbing out of poverty, falling back in. Journal of Human Resources, 34(3), 557–588.

Stiglitz, J. E., Sen, A. K., & Fitoussi, J.-P. (2009). Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress [Electronic Article]. The Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. Retrieved February 11, 2011 from http://www.stiglitz-sen-fitoussi.fr/documents/rapport_anglais.pdf

Sugden, R. (1993). Review: Welfare, resources, and capabilities: A Review of inequality reexamined by Amartya Sen. Journal of Economic Literature, 31(4), 1947–1962.

Taylor, M. F., Brice, J., Buck, N., & Prentice-Lane, E. (2010). British Household Panel Survey user manual (Vols. A: Introduction, Technical report and Appendices). U.K.: University of Essex.

Thorbecke, E. (2005). Multidimensional poverty: Conceptual and measurement issues [Conference Paper]. UNDP International Poverty Centre. Auguest 29–31, 2005.

Thorbecke, E. (2007). Multidimensional poverty: Conceptual and measurement issues. In N. Kakwani & J. Silber (Eds.), The many dimensions of poverty. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Tomer, J. F. (2002). Human well-being: A new approach based on overall and ordinary functionings. Review of Social Economy, 60(1), 23–45.

Tomlinson, M., Walker, R., & Williams, G. (2008). Measuring poverty in Britain as a multidimensional concept, 1991 to 2003. Journal of Social Policy, 37(04), 597–620.

Townsend, P. (1979a). Introduction: Concepts of poverty and deprivation. In P. Townsend (Ed.), Poverty in the United Kingdom: a survey of household resources and standards of living (pp. 31–62). London: Penguin Books.

Townsend, P. (1979b). Poverty in the United Kingdom: A survey of household resources and standards of living. London: Penguin Books.

Townsend, P. (1985). A sociological approach to the measurement of poverty: A rejoinder to Professor Amartya Sen. Oxford Economic Papers, 37(4), 659–668.

Valletta, R. G. (2006). The ins and outs of poverty in advanced economies: Government policy and poverty dynamics in Canada, Germany, Great Britain, and the United States. Review of Income and Wealth, 52(2), 261–284.

van Buuren, S. (2012). Flexible imputation of missing data. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Veit-Wilson, J. (1987). Consensual approaches to poverty lines and social security. Journal of Social Policy, 16(02), 183–211.

Volkert, J. (2006). European union poverty assessment: A capability perspective. Journal of Human Development, 7(3), 359–383.

Wagle, U. (2005). Multidimensional poverty measurement with economic well-being, capability, and social inclusion: A case from Kathmandu, Nepal. Journal of Human Development, 6(3), 301–328.

Wagle, U. (2008). Multidimensional poverty measurement: Concepts and applications. New York: Springer.

Wang, J., & Wang, X. (2012). Structural equation modeling: Applications using mplus. Chichester, UK: Higher Education Press.

Weinberg, D. H. (1991). Poverty dynamics and the poverty gap, 1984-86. The Journal of Human Resources, 26(3), 535–544.

Whelan, B. J. (1993a). Non-monetary Indicators of Poverty. In J. Berghman & B. Cantillon (Eds.), The European face of social security: Essays in honour of Herman Deleeck. Avebury: Brookfield, VT.

Whelan, C. T. (1993b). The role of social support in mediating the psychological consequences of economic stress. Sociology of Health and Illness, 15(1), 86–101.

Whelan, B. J., & Whelan, C. T. (1995). In What Sense is Poverty Multidimensional? In G. Room (Ed.), Beyond the threshold: The measurement and analysis of social exclusion (pp. 29–48). Bristol: The Policy Press.

Zheng, B. (1997). Aggregate poverty measures. Journal of Economic Surveys, 11(2), 123–162.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Indicators for Each Dimension and their Measurement

Dimension | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

Economic resources | Household income Financial situation | Annual household income for year 2005 Self-evaluation of personal financial situation |

Healtht | Health status | Health status over last 12 months |

Satisfaction with health | How satisfied with current health | |

Health inhibits activities | Whether health prohibits respondents from doing things they want to do | |

Employment | Permanent job | Current job status: permanent, temporary or no job |

Job security satisfaction | How satisfied with job security | |

Overall job satisfaction | Overall, how satisfied with job | |

Housing | Lack of adequate heating | Y/N question |

Leaky roof/Shortage of space Noise from neighbors Street noise/Condensation Not enough light/Damp walls Rot in windows and floors | Y/N question | |

Durable goods | TV/VCR/Freezer/Washer Dishwasher/Microwave/Computer/CDP Phone/Cellphone/Internet/Cars | Y/N question |

Social capital | Feed visitors once a month | Intention of feeding visitors once a month |

Talking to neighbors | Frequency of talking to neighbors | |

Meeting people | Frequency of meeting people (friends or relatives) at home or elsewhere | |

Local group activities | Frequency of attending meetings for local groups/vol- untary organizations | |

Voluntary works | Frequency of doing unpaid voluntary work |

Indicators | Measurement |

|---|---|

Income | Eight-fold income bracket (based on 15, 30, 45, 60, 75, 90 percentiles) |

Financial situation | 1 (Very difficult)—5 (living comfortably) |

Permanent job | 1 (Contractual), 2(seasonal), 3 (permanent) |

Job satisf. security | 1 (Not satisfied at all)–7 (completely satisfied) |

Job satisf. overall | 1 (Not satisfied at all)–7 (completely satisfied) |

Health status | 1 (Very poor)–5 (excellent) |

Satisf. health | 1 (Not satisfied at all)–7 (completely satisfied) |

Health inhibits activities | 1 (Yes), 2 (no) |

Feed visitors | 1 (No), 2 (yes) |

Talking to neighbors | 1 (Never)–5 (on most days) |

Meeting people | 1 (Never)–5 (on most days) |

Local group activities | 1(Never)–5 (at least once a week) |

Voluntary works | 1(Never)–5 (at least once a week) |

Housing | Average over 9 binary indicators |

Durable goods | Average over 12 binary indicators |

Appendix 2: Detailed Result for 1996

Unstandardized result

Estimate | S.E. | Est./S.E. | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Economic resources (econres) | ||||

Income (econres1) | 0.730 | 0.092 | 7.955 | 0.000 |

Financial situation (econres2) | 1.000 | 0.000 | 999.000 | 999.000 |

Employment (emp) | ||||

Permanent job (emp1) | 1.000 | 0.000 | 999.000 | 999.000 |

Job satisfaction: security (emp2) | 3.359 | 0.801 | 4.196 | 0.000 |

Job satisfaction: overall (emp3) | 3.135 | 0.712 | 4.401 | 0.000 |

Health (health) | ||||

Health status (health1) | 1.000 | 0.000 | 999.000 | 999.000 |

Satisfaction: health (health2) | 0.833 | 0.016 | 50.555 | 0.000 |

Health inhibits activities (health3) | 0.905 | 0.017 | 53.598 | 0.000 |

Social capital (scapital) | ||||

Feeding visitors (sc1) | 1.000 | 0.000 | 999.000 | 999.000 |

Local group acitvities (sc3) | 2.081 | 0.312 | 6.678 | 0.000 |

Voluntary works (sc4) | 2.624 | 0.339 | 7.745 | 0.000 |

Well-being | ||||

Durable goods (durablep) | 1.000 | 0.000 | 999.000 | 999.000 |

Housing (housep) | 0.328 | 0.044 | 7.458 | 0.000 |

Social Capital | 1.000 | 0.000 | 999.000 | 999.000 |

Economic resources | 4.128 | 0.374 | 11.028 | 0.000 |

Health | 5.369 | 0.531 | 10.117 | 0.000 |

Employment | 0.617 | 0.167 | 3.699 | 0.000 |

Correlated variables | ||||

Scapital with emp | −0.002 | 0.003 | −0.560 | 0.576 |

Sc3 with sc4 | 0.444 | 0.068 | 6.520 | 0.000 |

Durablep with econres1 | 0.077 | 0.006 | 12.045 | 0.000 |

Durablep with sc1 | 0.050 | 0.005 | 9.887 | 0.000 |

Sc1 with econres2 | 0.187 | 0.021 | 9.016 | 0.000 |

Sc1 with econres1 | 0.258 | 0.027 | 9.617 | 0.000 |

Housep with econres2 | 0.022 | 0.003 | 8.410 | 0.000 |

Health3 with econres1 | 0.211 | 0.029 | 7.188 | 0.000 |

Standardized result

Estimate | S.E. | Est./S.E. | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Economic resources (econrres) | ||||

Income (econres1) | 0.528 | 0.038 | 14.032 | 0.000 |

Financial situation (econres2) | 0.723 | 0.048 | 15.163 | 0.000 |

Employment (emp) | ||||

Permanent job (emp1) | 0.222 | 0.048 | 4.593 | 0.000 |

Job satisfaction: security (emp2) | 0.747 | 0.059 | 12.646 | 0.000 |

Job satisfaction: overall (emp3) | 0.698 | 0.057 | 12.274 | 0.000 |

Health (health) | ||||

Health status (health1) | 0.916 | 0.009 | 100.510 | 0.000 |

Satisfaction: health (health2) | 0.763 | 0.010 | 76.668 | 0.000 |

Health inhibits activities (health3) | 0.829 | 0.012 | 71.516 | 0.000 |

Social capital (scapital) | ||||

Feeding visitors (sc1) | 0.229 | 0.025 | 9.324 | 0.000 |

Local group acitvities (sc3)0.476 | 0.069 | 6.922 | 0.000 | |

Voluntary works(sc4) | 0.601 | 0.074 | 8.071 | 0.000 |

Well-being | ||||

Durable goods (durablep) | 0.402 | 0.025 | 16.319 | 0.000 |

Housing (housep) | 0.219 | 0.025 | 8.725 | 0.000 |

Social capital | 0.445 | 0.047 | 9.556 | 0.000 |

Economic resources | 0.582 | 0.042 | 13.800 | 0.000 |

Health | 0.597 | 0.034 | 17.768 | 0.000 |

Employment | 0.283 | 0.040 | 7.031 | 0.000 |

Correlated variables | ||||

Scapital with emp | −0.041 | 0.073 | −0.561 | 0.575 |

Sc3 with sc4 | 0.631 | 0.038 | 16.643 | 0.000 |

Durablep with econres1 | 0.390 | 0.026 | 14.781 | 0.000 |

Durablep with sc1 | 0.222 | 0.022 | 10.089 | 0.000 |

Sc1 with econres2 | 0.278 | 0.038 | 7.300 | 0.000 |

Sc1 with econres1 | 0.312 | 0.033 | 9.399 | 0.000 |

Housep with econres2 | 0.212 | 0.026 | 8.266 | 0.000 |

Health3 with econres1 | 0.445 | 0.062 | 7.172 | 0.000 |

Correlation residual

Econres1 | Econres2 | Health1 | Health2 | Health3 | Emp1 | Emp2 | Emp3 | Sc1 | Sc3 | Sc4 | Housep | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Econres1 | ||||||||||||

Econres2 | 0.000 | |||||||||||

Health1 | 0.068 | 0.001 | ||||||||||

Health2 | −0.017 | 0.017 | 0.001 | |||||||||

Health3 | 0.000 | −0.052 | −0.008 | 0.009 | ||||||||

Emp1 | 0.098 | 0.076 | −0.004 | −0.003 | 0.003 | |||||||

Emp2 | −0.093 | 0.007 | −0.005 | 0.087 | −0.029 | 0.072 | ||||||

Emp3 | −0.123 | 0.062 | 0.023 | 0.142 | −0.078 | −0.180 | 0.003 | |||||

Sc1 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.091 | 0.073 | 0.126 | 0.030 | 0.006 | 0.038 | ||||

Sc3 | 0.015 | 0.040 | 0.023 | −0.055 | −0.047 | −0.083 | −0.026 | 0.049 | −0.004 | |||

Sc4 | −0.046 | −0.009 | 0.019 | −0.044 | 0.018 | −0.132 | −0.031 | 0.021 | 0.003 | 0.000 | ||

Housep | 0.005 | 0.000 | −0.003 | 0.003 | −0.011 | 0.019 | 0.007 | 0.005 | 0.020 | 0.008 | −0.002 | 0.000 |

Durablep | 0.000 | 0.006 | −0.002 | −0.022 | 0.029 | 0.023 | −0.032 | −0.031 | 0.000 | −0.003 | 0.011 | −0.001 |

Appendix 3: Unstandardized Factor Loadings

1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Income | 0.730*** (0.092) | 0.807*** (0.056) | 0.738*** (0.056) | 0.900*** (0.043) | 0.680*** (0.047) | 1.003*** (0.063) | 0.978*** (0.041) | 0.749*** (0.040) | 0.723*** (0.034) | 0.589*** (0.060) | 0.689*** (0.041) | 0.844*** (0.063) | 1.231*** (0.084) |

Financial situation | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000)(0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 | 1.000 (0.000) |

Permanent job | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 0.278*** (0.048) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) |

Job satisf.Security | 3.359*** (0.801) | 1.266*** (0.135) | 5.065*** (0.935) | 1.353*** (0.223) | 9.012 (4.915) | 2.756*** (0.395) | 1.967*** (0.418) | 5.203*** (1.220) | 1.088*** (0.103) | 1.000 (0.000) | 3.025*** (0.537) | 5.358** (1.822) | 2.911** (0.839) |

Job satisf.Overall | 3.135*** (0.712) | 1.759*** (0.128) | 3.247*** (0.522) | 0.242** (0.076) | 6.893 (4.020) | 2.400*** (0.311) | 0.348** (0.118) | 7.075*** (1.762) | 1.566*** (0.101) | 0.885*** (0.071) | 3.237*** (0.588) | 5.532** (2.016) | 3.717** (1.111) |

Health status | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) |

Satisf.Health | 0.833*** (0.016) | 0.887*** (0.010) | 0.838*** (0.013) | 0.819*** (0.010) | 0.811*** (0.014) | 0.821*** (0.008) | 0.805*** (0.008) | 0.796*** (0.018) | 0.846*** (0.013) | 0.846*** (0.014) | 0.839*** (0.013) | 0.831*** (0.019) | |

Health inhibits activities | 0.905*** (0.017) | 0.939*** (0.010) | 0.901*** (0.013) | 0.794*** (0.010) | 0.866*** (0.015) | 1.080*** (0.049) | 0.932*** (0.009) | 0.890*** (0.009) | 0.527*** (0.015) | 0.928*** (0.013) | 0.910*** (0.014) | 0.903*** (0.014) | 0.938*** (0.019) |

Feed visitors | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | |

Talking to neighbors | −0.009 (0.024) | 0.752*** (0.133) | 0.330*** (0.068) | 0.629*** (0.126) | 1.000 (0.000) | 0.402*** (0.085) | 0.839*** (0.133) | 1.522*** (0.226) | 0.578*** (0.124) | 0.515*** (0.102) | 0.430*** (0.109) | −0.008 (0.097) | |

Meeting people | 0.224*** (0.063) | 0.406*** (0.115) | −0.090 (0.068) | 0.145 (0.107) | −0.273 (0.164) | −0.029 (0.082) | −0.229* (0.113) | 0.215 (0.148) | 0.310** (0.115) | 0.430*** (0.099) | 0.366*** (0.105) | 0.362** (0.109) | |

Local group activities | 2.081*** (0.312) | 0.157** (0.053) | 1.627*** (0.270) | 2.168*** (0.185) | 4.739*** (0.545) | 2.628*** (0.330) | 2.611*** (0.202) | 2.670*** (0.281) | 2.963*** (0.289) | 1.868*** (0.297) | 0.992*** (0.154) | 1.299*** (0.227) | 2.302*** (0.216) |

Voluntary works | 2.624*** (0.339) | 0.162* (0.064) | 1.949*** (0.305) | 1.203*** (0.150) | 5.367*** (0.614) | 1.397*** (0.397) | 2.699*** (0.215) | 1.062** (0.317) | 2.812*** (0.302) | 1.176*** (0.229) | 1.081*** (0.168) | 0.949*** (0.208) | 1.124*** (0.158) |

Economic resources | 4.128*** (0.374) | 5.997*** (0.341) | 4.488*** (0.632) | 5.480*** (0.221) | 15.127*** (2.021) | 5.809*** (0.405) | 6.959*** (0.320) | 7.548*** (0.361) | 11.826*** (0.647) | 4.956*** (0.375) | 4.767*** (0.279) | 3.612*** (0.246) | 2.835*** (0.222) |

Employment | 0.617*** (0.167) | 2.191*** (0.218) | 0.315*** (0.083) | 1.296*** (0.216) | 0.573 (0.331) | 0.795*** (0.139) | 1.652*** (0.360) | 0.670*** (0.167) | 3.474*** (0.307) | 3.720*** (0.354) | 0.549*** (0.108) | 0.315** (0.116) | 0.533** (0.162) |

Health | 5.369*** (0.531) | 5.772*** (0.340) | 2.202*** (0.374) | 3.588*** (0.249) | 9.397*** (1.309) | 4.876*** (0.348) | 6.529*** (0.300) | 5.930*** (0.267) | 7.491*** (0.378) | 6.065*** (0.525) | 3.086*** (0.191) | 4.112*** (0.438) | 3.859*** (0.232) |

Social capital | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) |

Durable goods | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) |

Housing | 0.328*** (0.044) | 0.427*** (0.036) | 0.645*** (0.054) | 0.399*** (0.023) | 0.920*** (0.128) | 0.439*** (0.035) | 0.437*** (0.029) | 0.454*** (0.030) | 0.788*** (0.044) | 0.322*** 0.036) | 0.283*** (0.020) | 0.229*** (0.024) | 0.198*** (0.027) |

Model fit statistics

Year | Sample size | χ2 | D.F. | P value | CFIa | TLI | RMSEA | Testb | WRMRc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1996 | 4850 | 473.87 | 54 | 0.00 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.04 | 1.00 | 1.87 |

1997 | 11,193 | 1041.95 | 71 | 0.00 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.04 | 1.00 | 2.54 |

1998 | 10,906 | 823.11 | 72 | 0.00 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.03 | 1.00 | 2.26 |

1999 | 15,623 | 975.41 | 65 | 0.00 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.03 | 1.00 | 2.44 |

2000 | 15,603 | 548.00 | 68 | 0.00 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.02 | 1.00 | 1.86 |

2001 | 18,867 | 685.23 | 55 | 0.00 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.02 | 1.00 | 2.33 |

2002 | 16,597 | 893.57 | 66 | 0.00 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.03 | 1.00 | 2.32 |

2003 | 16,238 | 837.38 | 66 | 0.00 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.03 | 1.00 | 2.26 |

2004 | 15,791 | 685.50 | 66 | 0.00 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.02 | 1.00 | 2.05 |

2005 | 15,617 | 851.13 | 78 | 0.00 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.02 | 1.00 | 2.32 |

2006 | 15,392 | 859.47 | 77 | 0.00 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.03 | 1.00 | 2.33 |

2007 | 14,873 | 782.83 | 74 | 0.00 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.02 | 1.00 | 2.21 |

2008 | 7746 | 726.37 | 81 | 0.00 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.03 | 1.00 | 2.12 |

Appendix 4: Unstandardized Factor Loadings After Multiple Imputation

1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Income | 0.656*** (0.095) | 0.750*** (0.056) | 0.674*** (0.060) | 0.882*** (0.041) | 0.637*** (0.034) | 0.845*** (0.038) | 0.854*** (0.061) | 0.681*** (0.038) | 0.691*** (0.035) | 0.468*** (0.051) | 0.667*** (0.044) | 0.739*** (0.063) | 0.945*** (0.056) |

Financial situation | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) |

Permanent job | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 0.408*** (0.036) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) |

Job satisf. security | 2.567*** (0.565) | 1.222*** (0.134) | 4.001*** (0.763) | 2.032*** (0.538) | 3.241*** (0.460) | 1.902*** (0.098) | 2.774 (1.617) | 3.204*** (0.538) | 1.143*** (0.118) | 1.000 (0.000) | 2.357*** (0.383) | 3.064** (0.881) | 1.366*** (0.197) |

Job satisf. overall | 2.039*** (0.499) | 1.589*** (0.126) | 2.531*** (0.388) | 0.892** (0.273) | 3.371*** (0.584) | 1.468*** (0.101) | 1.210 (0.881) | 4.289*** (0.983) | 1.523*** (0.087) | 0.913*** (0.050) | 2.766*** (0.500) | 3.391** (1.084) | 1.536*** (0.288) |

Health status | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) |

Satisf. health | 0.852*** (0.018) | 0.900*** (0.010) | 0.846*** (0.014) | 0.818*** (0.010) | 0.823*** (0.009) | 0.833*** (0.008) | 0.820*** (0.009) | 0.822*** (0.018) | 0.854*** (0.013) | 0.867*** (0.014) | 0.853*** (0.013) | 0.854*** (0.016) | |

Health inhibits activities | 0.912*** (0.018) | 0.943*** (0.010) | 0.902*** (0.013) | 0.790*** (0.010) | 0.913*** (0.009) | 1.053*** (0.032) | 0.941*** (0.008) | 0.900*** (0.010) | 0.620*** (0.018) | 0.928*** (0.013) | 0.920*** (0.014) | 0.911*** (0.015) | 0.946*** (0.023) |

Feed visitors | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | |

Talking to neighbors | −0.006 (0.092) | 0.789*** (0.153) | 0.416*** 1.673** | (0.026) (0.267) | (0.148) 0.573*** | (0.081) 0.431*** | 0.499* 0.478** | (0.080) 0.108 | 1.000 (0.127) | (0.000) (0.109) | 0.450*** (0.149) | 0.930** (0.106) | |

Meeting people | 0.242*** (0.065) | 0.448** (0.141) | −0.024 (0.079) | 0.104 (0.072) | −0.378*** (0.120) | 0.046*** (0.099) | −0.105*** (0.125) | 0.378*** (0.179) | 0.247*** (0.115) | 0.405** (0.123) | 0.484*** (0.131) | 0.105*** (0.111) | |

Local group activities | 2.358*** (0.429) | 0.158** (0.055) | 1.882*** (0.310) | 2.524*** (0.224) | 4.708*** (0.387) | 2.474*** (0.229) | 2.595*** (0.209) | 2.422*** (0.307) | 2.841*** (0.320) | 2.135*** (0.294) | 1.244*** (0.177) | 1.283*** (0.285) | 2.493*** (0.238) |

Voluntary works | 3.020*** (0.449) | 0.175* (0.069) | 2.277*** (0.348) | 1.403*** (0.176) | 5.032*** (0.407) | 1.477*** (0.285) | 2.659*** (0.220) | 1.100** (0.332) | 2.770*** (0.328) | 1.368*** (0.253) | 1.497*** (0.206) | 0.959*** (0.247) | 1.438*** (0.168) |

Economic resources | 5.008*** (0.606) | 6.767*** (0.444) | 6.911*** (1.021) | 6.253*** (0.326) | 14.796*** (1.647) | 7.212*** (0.335) | 7.398*** (0.382) | 7.995*** (0.398) | 11.709*** (0.772) | 5.705*** (0.407) | 4.695*** (0.331) | 3.957*** (0.281) | 3.689*** (0.314) |

Employment | 1.286** (0.456) | 2.750*** (0.266) | 0.670* (0.260) | 1.456*** (0.351) | 1.909*** (0.374) | 1.473*** (0.114) | 1.788* (0.787) | 1.441*** (0.303) | 4.464*** (0.384) | 3.767*** (0.311) | 0.836*** (0.148) | 0.863** (0.274) | 1.760*** (0.327) |

Health | 6.308*** (0.920) | 6.285*** (0.401) | 3.293*** (0.546) | 4.933*** (0.411) | 10.824*** (1.221) | 5.176*** (0.217) | 7.386*** (0.395) | 6.709*** (0.400) | 8.314*** (0.460) | 5.646*** (0.420) | 3.414*** (0.338) | 5.573*** (0.655) | 4.507*** (0.447) |

Social capital | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) |

Durable goods | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) | 1.000 (0.000) |

Housing | 0.391*** (0.065) | 0.460*** (0.042) | 0.679*** (0.059) | 0.481*** (0.029) | 1.163*** (0.132) | 0.552*** (0.025) | 0.466*** (0.033) | 0.450*** (0.031) | 0.780*** (0.054) | 0.376*** (0.036) | 0.261*** (0.024) | 0.242*** (0.029) | 0.241*** (0.036) |

Appendix 5: Standardized Factor Loadings after Multiple Imputation

1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Income | 0.500*** (0.040) | 0.504*** (0.023) | 0.458*** (0.025) | 0.567*** (0.016) | 0.474*** (0.015) | 0.570*** (0.015) | 0.539** (0.022) | 0.476*** (0.016) | 0.484*** (0.015) | 0.372*** (0.024) | 0.471*** (0.019) | 0.473*** (0.025) | 0.570*** (0.023) |

Financial situation | 0.764** (0.056) | 0.672*** (0.026) | 0.679*** (0.032) | 0.643*** (0.016) | 0.744*** (0.020) | 0.674*** (0.017) | 0.632*** (0.023) | 0.698*** (0.021) | 0.701*** (0.020) | 0.795*** (0.044) | 0.707*** (0.027) | 0.640*** (0.030) | 0.604*** (0.025) |

Permanent job | 0.319** (0.056) | 0.510*** (0.040) | 0.230*** (0.037) | 0.451*** (0.061) | 0.210*** (0.031) | 0.423*** (0.021) | 0.378*** (0.104) | 0.192** (0.035) | 0.536*** (0.039) | 0.308*** (0.025) | 0.281*** (0.049) | 0.235*** (0.059) | 0.505*** (0.079) |

Job satisf.Security | 0.805*** (0.112) | 0.621*** (0.026) | 0.913*** (0.061) | 0.900*** (0.119) | 0.677*** (0.034) | 0.803*** (0.023) | 0.999** (0.311) | 0.607*** (0.027) | 0.610*** (0.022) | 0.756*** (0.021) | 0.652*** (0.032) | 0.692*** (0.035) | 0.681*** (0.040) |

Job satisf.Overall | 0.636*** (0.084) | 0.808*** (0.035) | 0.579*** (0.045) | 0.394*** (0.074) | 0.702*** (0.031) | 0.619*** (0.021) | 0.430* (0.204) | 0.806*** (0.031) | 0.815*** (0.031) | 0.690*** (0.020) | 0.763*** (0.036) | 0.762*** (0.038) | 0.760*** (0.045) |

Health status | 0.908*** (0.010) | 0.887*** (0.005) | 0.907*** (0.007) | 0.912*** (0.006) | 0.913*** (0.005) | 0.856*** (0.013) | 0.905*** (0.004) | 0.925*** (0.005) | 0.921*** (0.010) | 0.899*** (0.007) | 0.894*** (0.007) | 0.912*** (0.007) | 0.903*** (0.011) |

Satisf.Health | 0.774*** (0.011) | 0.799*** (0.006) | 0.767*** (0.008) | 0.746*** (0.006) | 0.751*** (0.006) | 0.754*** (0.005) | 0.758*** (0.006) | 0.757*** (0.009) | 0.767*** (0.008) | 0.775*** (0.008) | 0.778*** (0.007) | 0.771*** (0.011) | |

Health inhibits activities | 0.828*** (0.012) | 0.837*** (0.007) | 0.818*** (0.009) | 0.721*** (0.007) | 0.833*** (0.006) | 0.902*** (0.014) | 0.852*** (0.006) | 0.832*** (0.006) | 0.571*** (0.018) | 0.834*** (0.009) | 0.822*** (0.010) | 0.831*** (0.010) | 0.854*** (0.016) |

Feed visitors | 0.213*** (0.025) | 0.747*** (0.103) | 0.240*** (0.025) | 0.267*** (0.017) | 0.180*** (0.013) | 0.193*** | 0.206*** (0.012) | 0.217*** (0.020) | 0.143*** (0.016) | 0.288*** (0.028) | 0.315*** (0.028) | 0.340*** (0.039) | 0.291*** (0.021) |

Talking to neighbors | −0.004 (0.019) | 0.190*** (0.030) | 0.111*** (0.020) | 0.090*** (0.012) | (0.017) | 0.093*** (0.018) | 0.202*** (0.028) | 0.238*** (0.025) | 0.165*** (0.032) | 0.136*** (0.033) | 0.163** (0.047) | 0.032 (0.031) | |

Meeting people | 0.181*** (0.028) | 0.107** (0.031) | −0.006 (0.021) | 0.019 (0.013) | −0.073** (0.022) | 0.009 (0.020) | −0.023 (0.027) | 0.054* (0.024) | 0.071* (0.032) | 0.128** (0.040) | 0.165*** (0.041) | 0.031 (0.032) | |

Local group activities | 0.500*** (0.079) | 0.118*** (0.031) | 0.452*** (0.058) | 0.673*** (0.043) | 0.845*** (0.027) | 0.477*** (0.043) | 0.536*** (0.040) | 0.525*** (0.054) | 0.404*** (0.041) | 0.615*** (0.061) | 0.391*** (0.048) | 0.435*** (0.075) | 0.726*** (0.051) |

Voluntary works | 0.641*** (0.084) | 0.130** (0.042) | 0.547*** (0.062) | 0.374*** (0.039) | 0.904*** (0.029) | 0.285*** (0.052) | 0.549*** (0.041) | 0.239** (0.070) | 0.394*** (0.042) | 0.394*** (0.060) | 0.471*** (0.054) | 0.326*** (0.074) | 0.419*** (0.038) |

Economic resources | 0.572*** (0.049) | 0.741*** (0.033) | 0.773*** (0.052) | 0.891*** (0.037) | 0.801*** (0.030) | 0.886*** (0.022) | 0.812*** (0.023) | 0.784*** (0.028) | 0.860*** (0.029) | 0.618*** (0.037) | 0.859*** (0.036) | 0.669*** (0.045) | 0.781*** (0.043) |

Employment | 0.343*** (0.066) | 0.397*** (0.021) | 0.219*** (0.054) | 0.294*** (0.038) | 0.366*** (0.026) | 0.289*** (0.021) | 0.324*** (0.061) | 0.511*** (0.024) | 0.430*** (0.025) | 0.429*** (0.022) | 0.387*** (0.036) | 0.392*** (0.033) | 0.446*** (0.037) |

Health | 0.604*** (0.044) | 0.522*** (0.022) | 0.276*** (0.031) | 0.495*** (0.021) | 0.477*** (0.019) | 0.501*** (0.013) | 0.566*** (0.017) | 0.497*** (0.016) | 0.465*** (0.017) | 0.540*** (0.021) | 0.493*** (0.027) | 0.659*** (0.037) | 0.638*** (0.035) |

Social capital | 0.412*** (0.050) | 0.099*** (0.014) | 0.317*** (0.032) | 0.344*** (0.022) | 0.225*** (0.016) | 0.430*** (0.039) | 0.336*** (0.021) | 0.316*** (0.028) | 0.362*** (0.035) | 0.299*** (0.029) | 0.411*** (0.046) | 0.318*** (0.041) | 0.440*** (0.034) |

Durable goods | 0.375*** (0.033) | 0.358*** (0.015) | 0.339*** (0.032) | 0.411*** (0.021) | 0.205*** (0.021) | 0.395*** (0.012) | 0.346*** (0.012) | 0.355*** (0.014) | 0.270*** (0.014) | 0.303*** (0.017) | 0.426*** (0.026) | 0.342*** (0.025) | 0.412*** (0.021) |

Housing | 0.223*** (0.027) | 0.217*** (0.017) | 0.369*** (0.031) | 0.230*** (0.012) | 0.320*** (0.013) | 0.311*** (0.011) | 0.226*** (0.012) | 0.233*** (0.014) | 0.298*** (0.013) | 0.246*** (0.020) | 0.264*** (0.018) | 0.195*** (0.022) | 0.218*** (0.030) |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, SG. What Have We Called as “Poverty”? A Multidimensional and Longitudinal Perspective. Soc Indic Res 129, 229–276 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1101-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1101-8