Abstract

The paper provides an overview of definitions, measurements and applications of the concept of multidimensional poverty through a systematic review. The literature is classified according to three research questions: (1) what are the main definitions of multidimensional poverty?; (2) what methods are used to measure multidimensional poverty?; (3) what are the dimensions empirically measured?. Findings indicate that (1) the research on multidimensional poverty has grown in recent years; (2) multidimensional definitions do not necessarily imply to leave behind the dominance of the economic sphere; (3) the most popular methods proposed in the literature deal with the Alkire–Foster methodology, followed by latent variable models. Recommendations for future research emerge: new methodologies or the improvement of current ones are rather relevant; intangible aspects of poverty start to deserve attention calling for new definitions; there is evidence of under researched geographical areas, thereby calling for new empirical works that expand the geographical scope.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The human capital is an essential resource for the growth of a country. Individuals or groups who are in poverty have to be helped to improve their conditions in order to experience a dignified life. With this in mind, poverty, its understanding, measuring, and reduction are at the center of socio-economic and political programs of governments in developing and non-developing countries. In particular, the way how it is measured determines the directions of governments’ lines of interventions. The other side of poverty is wealth. As reported in Peichl and Pestel (2013, p. 4551) “the rich are an important source of both economic growth and inequality and have considerable economic and political power.” Therefore, in terms of design of public policies it becomes important not only who the poor are but also who the rich are.

We started our review from the belief, not new in the literature (see for example Petrillo 2018), that people well-being is far from being a unidimensional concept based only on the monetary aspects (i.e. income). Instead, other aspects of human life have to be included in order to enrich the idea of well-being.

As a matter of fact, the conceptualization of poverty ranges from income and/or consumption-based definitions to others that consider its multidimensional nature and its many manifestations: lack of productive resources to sustain livelihoods, limited or no access to basic services such as water, health and education, malnutrition, increased morbidity and mortality, living in an unsafe or insecure environment, poor or no housing, lack of participation in social, cultural and political life, social exclusion (Botchway 2013).

Originally, the literature on poverty has dwelt a great deal on the economic dimension as poverty manifestations and measurement were based on the GDP (at a national level) and on the poverty line.

Only recently, poverty has been increasingly conceptualized and measured from a multidimensional perspective in order to provide policy makers and the general public with the necessary tools for effectively monitoring social changes (Iglesias et al. 2017). For instance, policy makers who have often underestimated the need to define poverty multidimensionally (Kana Zeumo et al. 2011), started to consider it as a multidimensional concept. A number of factors made the multidimensional poverty concept appealing to them: (1) different measurements based on single indicators may produce different results (Lister 2004; Barnes et al. 2002) and the consideration of multidimensionality may prevent such a risk when policy makers evaluate policy impacts and targets to reduce poverty, (2) as income-based poverty and multidimensional poverty do not overlap, policies need to be addressed to different aspects of citizens’ lives, other than economic wellness.

However, such a relatively new conceptualization is still far from consolidation (Aaberge and Brandolini 2014). Furthermore, how many aspects of multidimensionality are jointly measured remains still an open debate.

Yet this growing literature is highly fragmented and to the authors’ knowledge no systematic review has been recently carried out on the concept of multidimensional poverty. It is acknowledged that a systematic literature review is considered the gold standard for evidence assessment and it is “the most efficient and high-quality method for identifying and evaluating extensive literature” (Mulrow 1994). It makes explicit the values and assumptions underpinning a review and enhances the legitimacy and authority of the resulting evidence (Tranfield et al. 2003). Systematic reviews use a rigorous method of study selection and data extraction and typically involve a detailed and comprehensive plan and search strategy derived a priori that reduce selection bias, which is very common in narrative reviews.

Using the systematic literature review (SLR) methodology, the aim of this paper is to identify the main definitions of poverty, to review how the concepts of “multidimensional poverty” and “multidimensional poverty measurement” have been developed, and which are the dimensions considered in empirical analysis, ultimately.

This specific objective leads to the achievement of a more general goal, which is to serve as a bibliometric reference for researchers who will need to deal with the topic of multidimensional poverty in the three areas investigated: definitions, methods, and empirical analysis.

Specifically, the method followed is the SLR procedure as transferred from medicine to business and economics research by Tranfield et al. (2003), employing specific criteria for inclusion and exclusion of articles in and from the review.

Through the SLR we aim at identifying the main definitions of poverty with special emphasis on different aspects encompassed in the definition, the methods proposed in the literature to study the multidimensional concept of poverty, and the dimensions included in the empirical applications.

A total of 229 articles were finally included. The key information related to these articles was stored in a data repositoryFootnote 1 specifically designed for recording their characteristics. After that, the main information has been summarized and discussed. The most relevant findings of the SLR can be outlined as follows. First, the analysis of the definitions of multidimensional poverty showed that only few studies proposed a new definition (10 studies out of 229). Also, most definitions included the income-based poverty as focus. Second, among the new methodological proposals, the relative majority of studies proposed modifications of the Alkire–Foster method (Alkire and Foster 2007, 2009, 2011a) in terms of weighting schemes or methods of identification and aggregation of the dimensions. Only few studies (about 10%) proposed a comparison among different methodological approaches. Last, with reference to empirical applications, it emerged that not all the hypothesized dimensions are jointly considered and there was not observed a uniform geographical coverage of the continents. In this respect, a lack of studies related to USA emerged. Moreover, a certain preference for secondary data was observed with a predominant use of surveys that clearly show the extant need of producing internationally comparable “poverty” data with harmonized questionnaires by country and by year.

The main contribution of the paper is to bring together in one single research the most relevant studies about multidimensional poverty in order to find possible avenues for future research.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the methodology employed to conduct the systematic review; Sect. 3 describes the main characteristics of the studies included in the final data repository and provides the results from an in-depth review of the studies; Sect. 4 summarizes the main findings, discusses and concludes.

2 Methodology of the literature review

According to the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins and Green 2011; Higgins et al. 2020) “A systematic review attempts to collate all empirical evidence that fits pre‐specified eligibility criteria in order to answer a specific research question. It uses explicit, systematic methods that are selected with a view to minimizing bias, thus providing more reliable findings from which conclusions can be drawn and decisions made”. The SLR here conducted follows three main stages—planning, executing, and reporting, as described in Tranfield et al. (2003). At the same time, we rely on the methodological guide summarized by Mohamed Shaffril et al. (2021), who have provided an all-encompassing and up-to-date guide to conducting systematic review for non-health researchers.

2.1 Planning

2.1.1 Conceptual development and research questions

Scholars and practitioners agree that one indicator alone cannot capture the multiple aspects of the poverty that is undisputedly considered a multidimensional concept (see Kana Zeumo et al. 2011 for a review).

According to the World Bank’s (2001) report, poverty is a state of deprivation which encompasses not only material but also non-material aspects. Furthermore, the concept of poverty is evolutive (Kana Zeumo et al. 2011) and its manifestations are related to the structures of the society and to the period in which poverty is discussed. Therefore, defining poverty is not a simple task as various studies do not agree on a common and conclusive definition.

With this in mind, we posit the following research question:

RQ1

What are the main definitions of poverty and related concepts proposed in a multidimensional setting?

Poverty measurement is a crucial task. Indeed, only through its measurement authorities and policy makers are able to quantify its extent, intensity, and potential effect so as to gauge subsequent actions. We start from considering that the operationalization of a multidimensional poverty concept has to deal with different theoretical and methodological choices (see Dewilde 2004). Therefore, technically speaking, the problem becomes how to construct a multidimensional index. With this in mind, we posit the following research question:

RQ2

What are the methods proposed to measure the multidimensional poverty concept?

Poverty can be declined with respect to several dimensions: income, human rights, food, education, health to cite the most common. However, in empirical contexts it may be difficult to effectively measure all the dimensions as assumed in conceptual frameworks. We expect that the literature review will reflect the fact that the notion of poverty has gradually been enlarged from an income-based to a multidimensional concept, and in the same fashion of Dewilde (2004), that the operationalization of the concept has not followed the same development. To put it differently, we might expect a mismatch between the dimensions conceptually developed and the number of dimensions empirically measured. In light of this view, we posit the following research question:

RQ3

What are the dimensions measured in empirical works?

2.2 Executing

2.2.1 Identification of studies and data collection

2.2.1.1 Selection of keywords

We selected keywords that in our conceptual view were relevant for finding articles addressing the afore mentioned research questions and that were specific enough to avoid the inclusion of non-relevant publications and formulated in order to avoid the exclusion of potentially relevant and insightful works.

The chosen keywords, namely, ‘multidimensional inequality’, ‘multidimensional poverty’, ‘multidimensional well-being’, and ‘multidimensional wellbeing’, all refer to the broad concept of poverty. The concept of poverty from a stand-alone viewpoint (e.g., income-only poverty) was not considered. It is worth to note that in the selection of keywords, we did not differentiate among terms that describe methodology (e.g., ‘measures’, ‘indicators’) or terms addressing the type of investigation (e.g., ‘case study’, ‘empirical’, ‘theoretical’, ‘analysis’).

2.2.1.2 Selection of databases

Like in other studies (e.g., Dangelico and Vocalelli 2017; Vivas and Barge-Gil 2015) we chose the following databases for this research: (a) Elsevier Scopus and (b) Clarivate Analytics Web of Science (WoS). Descriptions of the search options are provided in Table 1.

All databases were searched using the four abovementioned keywords. Table 2 reports the number of results obtained for each keyword within each database. Specifically, in the last two rows, the total numbers of retrieved studies within each database and across keywords (total, net of duplicates) are reported.

2.2.2 Selection of studies

Once the results of the searches reported in Table 2 were collected and the duplicated studies, within and across databases, were discharged, we obtained a list of 669 results that were archived in a Microsoft Excel file. In a SLR it is critical to operationally define which types of studies to include and exclude (Uman 2011). To this end, we decided to include studies that were clearly able to satisfy at least one of the three research questions (RQ1–RQ2–RQ3) reported in Sect. 2.1. In particular, we included studies which provide a new definition of poverty in a multidimensional setting, propose a new method to study multidimensional poverty, or deal with a real-data application to support evidence on this topic. The exclusion criteria were defined as follows:

-

1.

studies that did not strictly focus on the concept of multidimensional poverty as they did not propose a definition, a new method, or an application to real data on this topic;

-

2.

studies that dealt with “multidimensional inequality” only from a mathematical point of view;

-

3.

studies that dealt with economic or income aspects of poverty only, and therefore were not strictly considering a multidimensional concept;

-

4.

studies that focused on well-being from a medical point of view only;

-

5.

studies that did not focus on individuals or households, but, for example, on firms;

-

6.

studies that dealt with specific categories of subjects only (e.g., patients, children, females, people with disabilities, aging population, workers, …) as the main focus of the systematic review is on households or individuals in general and not on specific categories of the population;

-

7.

studies where multidimensional inequality was studied in relation to other aspects (e.g., mental health, gender) or as their determinant;

-

8.

theoretical studies investigating the statistical and mathematical properties of inequality measures already proposed in the literature, as their focus was not on proposing a new definition, method or an application to real data;

-

9.

studies that dealt with applications in a very limited geographical area (e.g. small rural areas of a specific region of a country, very small sample size);

-

10.

studies whose abstract did not clear up the focus of the study;

-

11.

studies where the dimensions considered were not clearly defined;

-

12.

reviews.

In this phase, it was important to balance sensitivity (retrieving a high proportion of relevant studies) with specificity (retrieving a low proportion of irrelevant studies). A total of 314 potentially relevant articles has been retrieved once the title and abstract were reviewed according to the above-mentioned inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.2.2.1 Study quality assessment

Once a comprehensive list of abstracts has been retrieved and reviewed, the 314 articles were fully analyzed and their quality was assessed. More precisely, as 14 full-text files were not available and 3 studies were written in Spanish or German,Footnote 2 a number of 297 studies were fully read. The final sample was reduced to a total of 229 articles (see a list of the studies in “Appendix”). The steps of the study selection process are reported in Fig. 1.

As shown in Fig. 1, we identified 608 records from Scopus and 531 from WoS, net of duplicates within each database. After removing duplicates, 669 abstracts were screened, which resulted in removing 355 records with not relevant abstract, leaving to 314 potentially relevant records to be screened by the lead authors. Of these 314 records, 68 not relevant, 14 with a not available full-text, and 3 not written in English articles were excluded, thus leaving a final sample of 229 studies to be included in the systematic review for data extraction.

The reason to exclude some articles was that they did not match any of the specified inclusion criteria, but matched at least one of the exclusion criteria, although this was not clear from the abstracts. Among the exclusion criteria previously defined, the top motives for the exclusions were:

-

the study was theoretical only (21 records; 25%);

-

the study did not answer to any of the three research questions and therefore does not strictly focus on multidimensional poverty (15 records; 18%);

-

the full-text was not available (14 records; 16%).

-

the study investigated multidimensional inequality in relation to other aspects (e.g., mental health, gender) or as their determinant (11 records; 13%);

-

the geographical area or the sample size were very limited (11 records; 13%);

-

the study focused on females or children only (4 records; 5%);

-

the dimensions of poverty considered in the study were not made explicit (3 records; 4%);

-

the language was not English (3 records; 4%);

-

the only dimension considered was income (2 records; 2%);

-

the study was a review (1 record; 1%).

The Pareto chart (Fig. 2) reports the top motives of exclusions along with their cumulative frequencies.

Apart from the fact that the study ‘only theoretical’ was the main exclusion criterion, the Pareto chart makes clear that ‘theoretical only’, ‘no match to any RQ’, ‘unavailable full-text’, ‘limited geographical area and/or sample size’ and ‘multidimensional inequality not the main focus’ together represent the 80% of the exclusion criteria.

2.2.2.2 Data extraction and data repository

Three types of information from each article were retrieved and stored in the data repository: (1) general information from the articles (authors, year, journal name, title, bibliographic database, keyword matching), (2) information about the matching with the three research questions (definition, method, application), and (3) information about the application, if any. For empirical applications, we reported the following details: methods of analysis, sample description (size, statistical units), geographical area (country or other), years covered, data collection type (cross sectional or longitudinal), data source (primary or secondary, source name), data representativeness (national, country comparisons), dimensions considered (economic/income, education, health, living standards, others), number and name of dimensions, number of indicators, main findings.

3 Reporting

3.1 Characteristics of studies included in the review

Figure 3 shows the distribution of studies over time and lead us to conclude that research associated with multidimensional poverty has grown in recent years. The year distribution of the sample is from 1999 to 2019. Over 60% of the sample is from studies published between 2015 and 2019.

The first study included in the review dates back to 1999. Until 2006 there has been a quite constant and limited number of studies, while after 2006 there has been an increase in the number of studies with a picking up speed starting from 2013 and a peak in 2019. Hence, most of the articles are recent, thus evidencing an increasing interest for poverty as a multi-dimensional concept in the literature.

Table 3 reports the name of the main journals where the reviewed studies were published. The journal that published most of the studies included in the review is “Social Indicator Research” (23% of studies), followed by “World Development” (4.8%) and by “The Journal of Economic Inequality” (4.4%). Interestingly, about 36% of the studies (82 out of 229) have been published in journals that host only one paper of this review. The journals publish work related to the economic, statistical, and social fields, mainly.

3.2 What is known about the multi-dimensional concept of poverty

Articles included in the review were classified into three different clusters (C1, C2, C3) according to the research questions they have addressed: (1) RQ1: what are the main definitions of poverty and related concepts in a multidimensional setting? (C1, 10 articles); (2) RQ2: what are the methods to measure the multidimensional poverty concept? (C2, 116 articles); and (3) RQ3: what are the relevant dimensions measured in empirical works? (C3, 214 articles). Table 4 reports the classification of the studies according to the three research questions. As can be noticed, the three clusters of studies examined were not mutually exclusive, as some of them (around 45%) addressed more than one research question. More in detail, as reported in Table 4, 111 studies answer to RQ3 only, 94 studies involve both methods and applications to real data (i.e., they satisfy both RQ2 and RQ3), 14 studies satisfy RQ2 only, 7 studies satisfy all the RQs, 2 studies provide both a definition of multidimensional poverty and an empirical application (RQ1 and RQ3), and only 1 paper has been classified as proposing both a definition and a method (RQ1 and RQ2).

In “Appendix”, the full list of articles included in the review is reported.

In the following sections, the evidence coming from the studies belonging to the three clusters are described (Table 5).

3.2.1 What are the main definitions of poverty and related concepts in a multidimensional setting?

About 4% of the articles from the review were classified into C1 (10 articles). Out of the ten articles from C1, three defined the poverty as a multidimensional concept with a clear mention of the dimensions to be considered in addition to economic and monetary dimensions. Two articles considered more than one dimension, but still limited the definition to the economic and material spheres only (e.g., Annoni et al. 2015). The remaining definitions went beyond the material and economic spheres and included intangible or fuzzy dimensions like, for instance, ‘achievements’, ‘quality of life’, ‘living right’.

What emerged from the above definitions was that the consideration of more than one dimension did not necessarily imply to overcome the dominance of economic and material aspects in the conceptualization of poverty. Nevertheless, new dimensions belonging to the non-material sphere complemented the material ones.

3.2.2 What are the methods to measure the multidimensional poverty concept?

Among the selected studies, 116 have been classified in cluster C2 as they answer the RQ2 research question by discussing methods to measure the multidimensional poverty concept. These studies proposed a new method or an alternative version (or improvement) of an existing method to investigate the multidimensionality structure of poverty, inequality, or well-being from an original point of view.

Examining the methods, 105 articles have been classified as reporting a single method, 10 articles using two methods, and 1 article as reporting a comparison of three methods. Table 6 shows the list of studies and their classification, where the studies reporting more than one method are identified by a star (see the note to Table 6). The second column of Table 6 shows the 11 studies that explicitly mention the Sen’s capability approach (Sen 1985) as theoretical framework of reference in their research. According to this approach, multidimensional well-being should be understood in terms of peoples’ capabilities to achieve valuable functionings (beings and doings), emphasizing their freedom to choose and achieve well-being. As a matter of fact, this approach has been developed as an alternative approach to the traditional “welfarist” approach focusing on the utility only. The capability approach represents a general principle and therefore needs to be operationalized through a specific method.

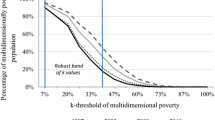

As can be seen in Table 6, the most frequently used methodology in the literature is the Alkire–Foster (AF) method (Alkire and Foster 2007, 2009, 2011a) and its extensions, which have been employed in 34 studies overall (about 29% of all the studies). Among these, 30 studies use the AF method only while 4 studies report the use of different methods, besides the AF one. The AF method builds on the Foster-Greer-Thorbecke (FGT) poverty measures (Foster et al. 1984) with the aim of constructing a multidimensional index of poverty (MPI). By adopting a flexible approach, different dimensions of poverty are identified as different types of deprivations. The method is based on the counting approach as it counts the weighted number of dimensions in which people suffer deprivation by defining proper cut-offs.

The main innovations introduced by the studies using the AF method deal with the following issues: weighting schemes, methods of identification and aggregation of the dimensions. In fact, as reported in Mitra et al. (2013), “the Alkire Foster method is sensitive to the selection of dimensions and the methods used to derive rankings and weights”. In Datt (2019), alternative weighting schemes, methods of identification and aggregation are proposed, finding evidence that the contribution of different dimensions involved in the estimation of multidimensional poverty may vary depending not only on the weighting schemes, but also on the interaction between them and the choices made in terms of identification and aggregation of dimensions. A new strategy for deriving weighting schemes comes from Cavapozzi et al. (2015), who proposed a hybrid approach based on the hedonic regression, where value judgements about the dimensions are combined to statistical evidence. With respect to the identification of the dimensions, a modification of the MPI was proposed by Nowak and Scheicher (2017) to include individuals who are extremely poor in only few dimensions and the differences with the respect to the original formulation have been showed in an empirical setting. Alkire et al. (2017), followed by Nicholas et al. (2019), combined the classical counting approach of the AF method (Alkire and Foster 2011a) for the analysis of multidimensional poverty at single time points, and the duration approach of Foster (2009) for over time analysis. In particular, Nicholas et al. (2019) showed that a large proportion of poverty may be attributed to over time deprivations. Finally, most studies propose modifications to the original formulation of the MPI based on the AF method by testing them in empirical settings (see, e.g., García-Pérez et al. 2017; Goli et al. 2019).

The second most commonly employed method is based on latent variables. Indeed, 15 articles (about 13%) have proposed latent variable models, such as factor analysis, or methods based on the concept of latent variables, such as principal component analysis or multiple correspondence analysis. In particular, one third of these studies use factor analysis, either in its confirmatory or exploratory version (see, e.g., Betti et al. 2015; Iglesias et al. 2017), one third use multiple correspondence analysis (see, e.g., Berenger et al. 2013), 4 of them use principal component analysis (see, e.g., Li et al. 2019) while, in the remaining study, latent class analysis based on discrete latent variables is proposed (Moonansingh et al. 2019). The aim of these studies has been to build a synthetic multidimensional measure of poverty or well-being, where each dimension is conceived as a latent, non-observable, construct. Particularly worthy of note is the fact that about half of the studies using latent variable models or methods are published in the journal “Social Indicators Research” (7 articles out of 15).

The third most frequently proposed method to study multidimensional poverty is the fuzzy theory (12 articles, 10%). Specifically, the fuzzy set theory is used to propose new weighting schemes for the poverty dimensions (see, e.g., Belhadj 2012, 2013) and to overcome the classical notion of binary poverty (poor or not poor) by using fuzzy measures (Behlhadj and Limam 2012; Betti et al. 2015).

A total of 8 articles (6.9%) use the Gini index and its generalization to the multidimensional case for studying multidimensional poverty (see, e.g. Banerjee 2010). In this field of literature, the Gini coefficient is used to measure the extent of inequality.

Moreover, the stochastic dominance and partial order theory have been proposed in 6 studies (about 5%) for synthetizing multidimensional data as opposed to the classical approaches based on composite indicators, such as the AF method or factor analysis. In particular, the posetic (partially ordered set) approach has been proposed in this field to deal with the issues of weighting and aggregating for ordinal data (Iglesias et al. 2017) by following the proposal of Fattore (2016) and Fattore et al. (2012). Interestingly, the studies by Fattore (2016) and Fattore et al. (2012) have not been included in the list of studies of our systematic review, despite they developed the initial proposal based on the posetic approach. Specifically, Fattore (2016) has not been included due to the choice of the research keys, which omitted the word “deprivation” while Fattore et al. (2012) is not a journal article.

In addition, a number of 4 studies (3.4%) use generalized mean aggregation as method for building multidimensional measures of well-being or poverty (see, e.g., Pinar 2019).

The 49 remaining studies (about 42%) use different methods from the ones reviewed above (“other”). The “other” category contains less common methods that are used in less than 4 studies. Among these methods, we find clustering (Kana Zeumo et al. 2014), structural equations and causal theory (Rodero-Cosano et al. 2014), spatial Bayesian models (Greco et al. 2019), and axiomatic approaches (Decanq et al. 2009; Croci Angelini and Michelangeli 2012).

To sum up, about half of the studies included in this SLR (116 out of 229) have been classified as proposing a method to synthetize multidimensional poverty or well-being. This means that introducing a new methodological approach or improving current approaches used in the literature is rather relevant in this research field. Despite the AF method is predominant, a number of different and minor approaches have been proposed which borrow from different research fields. Another interesting aspect that clearly emerges from the findings of this review is that most studies (about 90%) include an empirical application to show the effectiveness of the proposed method in practice. The presence of empirical results enriches the study of multidimensional poverty and well-being with data-based socio-economic interpretations. Finally, another finding is that most studies use a single methodological approach to analyze poverty data. Comparisons among different methods are rather uncommon and involve about 10% of the studies only.

3.2.3 What are the dimensions measured in empirical works?

A total of 214 articles (93.45% of the sample) were classified as C3.Footnote 3 The dimensions of poverty considered in the studies reviewed are reported in Fig. 4. The first most frequently dimension considered was ‘education’, followed by the second most frequently dimensions ‘health’ and ‘income’.

The dimensions reported in Fig. 4 are not mutually exclusive. This becomes clearer from Fig. 5 that reports the number of dimensions together considered in the studies reviewed. Only 6 studies out of 214 focused on a single dimension of poverty. The fact that they were included as considering poverty multidimensionally depends on the number of sub-items considered to measure the single dimension or in the case of the dimension ‘other’. In fact, under that category there may fall more than one dimension, such as ‘life satisfaction’, ‘civic engagement’, ‘women empowerment’, to cite a few. Moreover, 83 articles (around 39%) considered three dimensions and only around 9% considered all dimensions. Focusing on articles that considered three dimensions, we observed that the most frequent combination of poverty dimensions was “Education, Health, Living Standards” (37 studies out of 83, about 44.5%) followed by the combination “Income, Education, Health” (15 studies out of 83, about 18%), while the less frequent combination was “Education, Health, Other” (2 studies out of 83, about 2.4%).

The next descriptive analysis concerns the place where empirical studies refer to. The countries with the greatest number of studies were China (13), Pakistan (12) and India (11). Distributed by continent (Fig. 6), the studies were mainly made in Asia (30.84%, 66), in Europe (21.96%, 47) and in Africa (15.89%, 34). For some studies (9.35%, 20), the continent could not be clearly identified since the ‘many countries analysed’ may belong to different continents. Only six studies (2.8%) were found to refer to North America, in particular to the United States of America (USA). As the most powerful economy in the world, with one of the highest rates of poverty in the developed world, and an extreme extent of income and wealth inequality when compared to other industrialized countries, we could have expected the country to be one of the main fields of research. However, the USA does not predominate in empirical studies of multidimensional poverty. In this respect, the information presented in Fig. 6 gives researchers an important opportunity for empirical investigation on multidimensional poverty in the USA, as few relevant studies were identified in recent years in this review. On the other hand, Asian and European researchers in poverty wishing to study empirically the multidimensional poverty shall benefit of the various studies published on Asian or European countries for comparative purposes in order to provide more robust conclusions.

As a matter of fact, as shown in Fig. 7, apart from the categories ‘many OECD countries’, ‘Mediterranean countries’, ‘many countries’, within the same continent only few studies (e.g., related to Europe and South America) involve more than one country. This evidence calls for comparative studies among countries on multidimensional poverty.

Aiming to help future research on this subjects, the main data sources used by authors were also checked. A marked preference for secondary data (202 out of 214) was observed (Fig. 8).

Among secondary data type, it is evidenced that the use of surveys is still predominant. Notwithstanding the era of big data, survey research is still needed. Future works might explore the way how the two data sources may be used together in order to provide richer dataset and enhance poverty measurement.

Figure 9 focuses on the most researched continents, namely Asia and Europe, and for each one considers the main survey source. It clearly emerges that in Asia there is a fragmented use of surveys, while in Europe the use of EU-SILC data is predominant as it is a cross-sectional, longitudinal, harmonized survey with a full coverage of all European Union member states.

Moreover, from Fig. 10 another issue emerges: the inadequate timeliness, namely the period between the year when the study has been published and the reference period of the survey wave. However, it is acknowledged that such a weakness is common to all empirical studies that make use of secondary data produced by Bureaus of Statistics. This finding emerged from the SLR paves the way for future research that might experiment the combined use of traditional data sources (e.g., surveys, census and administrative data) and modern big data. Both data sources can significantly reduce the cost of reporting and improve the timeliness, as the data collection is less time and resource intensive than for conventional data.

4 Discussion and conclusions

The purpose of this paper was to provide a systematic framing of the literature on multi-dimensional poverty and related concepts until 2019. In particular, the review was conducted by querying the Scopus and the Web of Science databases, according to the keywords ‘multidimensional poverty’, ‘multidimensional inequality’, ‘multidimensional well-being’, and ‘multidimensional wellbeing’. A number of 669 studies was found, which was reduced to 314 after the abstract review. Next, the analysis of the full-text studies brought to the final number of 229 articles included in the review. Three main research questions were formulated to select and to analyze the studies, related to the definition of multidimensional poverty, the introduction of methods to synthetize and measure the multidimensional poverty, and the use of different dimensions in empirical applications.

The current work found that the amount of scientific literature devoted to enlarge the study of poverty or well-being from an income-based only perspective to a multidimensional one, has increased in the last few years, and especially from 2017 to 2019. In particular, besides the economic dimension, other three important poverty-related dimensions clearly emerged from the review: education, health, and living standards. However, one interesting finding is that the definitions of multidimensional poverty proposed in the literature often move around the income/consumption dimension, which has been considered as the main, most important conceptualization of poverty.

Another important issue which emerged from this study is that several different methods have been employed in the reviewed studies such as the fuzzy theory, the Gini index, and models and methods based on latent variables, but the most frequently used approach relies on the well-established Alkire–Foster method. In fact, the framework developed under the AF method for the measurement of multidimensional deprivations has turned to be very flexible so that it is currently used for large scale studies such as the computation of the multidimensional poverty index (MPI) by the United Nations, based on the three dimensions of health, education, and standard of living. Despite the primacy of the AF method, some limitations have been raised in the literature. Likely the main practical limitation is that the method requires that the data are available from the same survey and linked at the individual or household level (Alkire and Foster 2011b). Consequently, different data sources cannot be used, thus limiting the applicability of the method and, for example, the number of countries that could be compared within this framework. The investigation of multidimensional poverty measures based on the AF method requires efforts in collecting data uniformly and systematically. From the methodological point of view, as discussed in Sect. 3.2.2, the limitations identified in the literature are concerned with the sensitivity of the AF method to the methods of identification and aggregation of the dimensions and the weighting schemes. The authors of the AF method themselves identified some common misunderstandings of their approach in Alkire and Foster (2011b). In particular, they clarify that the method is sensitive to the joint distribution of deprivations, unlike other unidimensional or marginal methods, and that this is a distinctive feature of their proposal. The method represents a general framework for poverty measurement in a multidimensional perspective and should be operationalized by making proper choices which depend on the objectives of the single empirical studies.

The SLR here conducted allows us to conclude that the multidimensionality is not an unambiguous concept. Various dimensions may contribute to its definition and, notwithstanding we can observe frequently common dimensions (e.g., economic, health, education, living standards), their combined use is not obvious nor the items used to measure each specific dimension. On the empirical side, we found that some countries are under researched (e.g., USA). On the other hand, some geographical area, namely Asia or Europe, shall benefit of a vast empirical literature. Notwithstanding the high number of studies in these areas, a lack of comparative studies clearly emerged and paves the wave for future research. Moreover, a predominant use of surveys for data collection was observed that take along with it the often-inadequate timeliness issue. Future works might experiment the combined use of traditional surveys and new data sources based, for example, on big data.

It should be noted that the current literature review has some limitations. The most important one lies in the choices made during the systematic review design. Firstly, the review was solely restricted to the two “Scopus” and “Web of Science” databases since they represent the two biggest bibliographic databases covering literature from almost any discipline. Then, the research was limited to journal articles only. As a consequence, working papers, conference proceedings, books or book chapters, even if consistent with the research keys, were omitted from the results (for instance, the following references Alkire and Foster 2007, rev 2008, 2009; Fattore et al. 2012; Foster 2009; Sen 1985, were not caught by the queries). Thirdly, efforts were focused on articles published in English while articles published in other languages (despite the abstract in English) were excluded, as their inclusion may have increased challenges with respect to time and expertise in non-English languages, thus conducting to a knowledge loss. However, we are aware of the fact that limiting the SLR to English-only studies may increase the risk of bias. Future works may consider the inclusion of non-English studies in order to prevent such a risk.

An additional limitation is the time range of the systematic review, as the last publication year recorded is 2019. This choice is motivated by the fact that the following year 2020 has been characterized by the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. We believe that the difficult epidemiological situation, still affecting people’s life, may have deeply changed the impact of the different dimensions of poverty and gave much importance to dimensions such as psychological well-being, social exclusion, and technological and digital gaps. Future works might explore emerging issues related to poverty.

A natural progression of this work is to conduct a post-COVID systematic review of the literature including studies from 2020 onwards, considering a time horizon after the initial year of the COVID-19 pandemic of at least five years, and to compare the findings with the current ones.

Moreover, a limitation concerns the search method, which was through “keywords” (see Sect. 2.2.1). It is likely that some relevant articles that used different words in the title, abstract, keywords or topic were omitted from the systematic review. An example is the paper by Fattore (2016), cited in Sect. 3.2.2, which title contains the word “deprivation” instead of “poverty”, “well-being”, or “inequality” and was therefore excluded from the results. Future research might consider additional keywords such as: “social exclusion”, “deprivation”, “vulnerability”, “inequality of opportunity”, or “quality of life”. Moreover, future works might make use of text mining techniques to analyse in deep the occurrence of words in the definition and conceptualization of poverty in order to extrapolate the main dimensions considered behind the well-known group of four: health, economics, education, and living standards.

No less important, a limitation might lie in the fact that we do not suggest what is the best way to treat poverty from a multidimensional perspective, but simply analyse the trend of consideration of multidimensionality in scientific publications. After all, a systematic review has precisely the goal of bringing order in scientific publications by soughing and describing, in this particular case, the characteristics of the multidimensional poverty related papers in the considered period. In this respect, one might object that the adoption of a systematic review does not allow us to critically interrogate the extant literature, but solely to summarize/systematize extant knowledge. Consequently, future research avenue might opt for embracing a methodological approach that better suits a critical evaluation, like for instance the problematizing review (Alvesson and Sandberg 2020).

Notes

The data repository is available upon request.

Although these articles have an abstract written in English, the main text was not written in English.

The table with the summary of C3 articles is available upon request.

References

Aaberge, R., Brandolini, A.: Multidimensional poverty and inequality, Discussion Papers, No. 792, Statistics Norway, Research Department, Oslo (2014). Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/192774

Alkire, S., Foster, J.: Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement. J. Public Econ. 95, 476–487 (2011a)

Alkire, S., Foster, J.: Understandings and misunderstandings of multidimensional poverty measurement. J. Econ. Inequal. 9, 289–314 (2011b)

Alkire, S., Apablaza, M., Chakravarty, S., Yalonetzky, G.: Measuring chronic multidimensional poverty. J. Policy Model. 39(6), 983–1006 (2017)

Alkire, S., Foster, J.: Counting and Multidimensional Poverty Measurement. OPHI Working Paper 7, University of Oxford (2007, 2008)

Alkire, S., Foster, J.: Counting and Multidimensional Poverty Measurement. OPHI Working Paper 32, University of Oxford (2009)

Alvesson, M., Sandberg, J.: The problematizing review: a counterpoint to Elsbach and Van Knippenberg’s argument for integrative reviews. J. Manag. Stud. 57(6), 1290–1304 (2020)

Annoni, P., Bruggemann, R., Carlsen, L.: A multidimensional view on poverty in the European Union by partial order theory. J. Appl. Stat. 42(3), 535–554 (2015)

Banerjee, A.K.: A multidimensional Gini index. Math. Soc. Sci. 60(2), 87–93 (2010)

Barnes, M., Heady, C., Middelton, S., Millar, J., Papadopoulos, F., Tsakloglou, P.: Poverty and Social Exclusion in Europe. Edward Elgar, Northampton (2002)

Belhadj, B.: New weighting scheme for the dimensions in multidimensional poverty indices. Econ. Lett. 116(3), 304–307 (2012)

Belhadj, B.: New fuzzy indices for multidimensional poverty. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 24(3), 587–591 (2013)

Belhadj, B., Limam, M.: Unidimensional and multidimensional fuzzy poverty measures: new approach. Econ. Model. 29(4), 995–1002 (2012)

Bérenger, V., Deutsch, J., Silber, J.: Durable goods, access to services and the derivation of an asset index: comparing two methodologies and three countries. Econ. Model. 35, 881–891 (2013)

Betti, G., Gagliardi, F., Lemmi, A., Verma, V.: Comparative measures of multidimensional deprivation in the European Union. Empir. Econ. 49, 1071–1100 (2015)

Botchway, S.A.: Poverty: a review and analysis of its theoretical conceptions and measurements. Int. J. Human. Soc. Sci. 3(16), 85–96 (2013)

Cavapozzi, D., Han, W., Miniaci, R.: Alternative weighting structures for multidimensional poverty assessment. J. Econ. Inequal. 13, 425–447 (2015)

Closs, S.J., Dowding, D., Allcock, N., et al.: Towards improved decision support in the assessment and management of pain for people with dementia in hospital: a systematic meta-review and observational study. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library (Health Services and Delivery Research, No. 4.30.) Chapter 3, Meta-review: methods (2016). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK390801/

Croci Angelini, E., Michelangeli, A.: Axiomatic measurement of multidimensional well-being inequality: some distributional questions. J. Socio-Econ. 41(5), 548–557 (2012)

Dangelico, R.M., Vocalelli, D.: “Green marketing”: an analysis of definitions, strategy steps, and tools through a systematic review of the literature. J. Clean. Prod. 165, 1263–1279 (2017)

Datt, G.: Multidimensional poverty in the Philippines, 2004–2013: how much do choices for weighting, identification and aggregation matter? Empir. Econ. 57, 1103–1128 (2019)

Decancq, K., Decoster, A., Schokkaert, E.: The evolution of world inequality in well-being. World Dev. 37(1), 11–25 (2009)

Dewilde, C.: The multidimensional measurement of poverty in Belgium and Britain: a categorical approach. Soc. Indic. Res. 68, 331–369 (2004)

Fattore, M.: Partially ordered sets and the measurement of multidimensional ordinal deprivation. Soc. Indic. Res. 128, 835–858 (2016)

Fattore, M., Maggino, F., Colombo, E.: From composite indicators to partial orders: evaluating socio-economic phenomena through ordinal data. In: Maggino, F., Nuvolati, G. (eds.) Quality of Life in Italy: Research and Reflections, Social Indicators Research Series, 48th edn., pp. 41–68. Springer, Berlin (2012)

Foster, J.: A class of chronic poverty measures. In: Addison, A., Hulme, D., Kanbur, R. (eds.) Poverty Dynamics: Towards Inter-Disciplinary Approaches. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2009)

Foster, J., Greer, J., Thorbecke, E.: A class of decomposable poverty measures. Econometrica 52(3), 761–776 (1984)

García-Pérez, C., González-González, Y., Prieto-Alaiz, M.: Identifying the multidimensional poor in developed countries using relative thresholds: an application to Spanish data. Soc. Indic. Res. 131, 291–303 (2017)

Goli, S., Maurya, N.K., Moradhvaj, S., Bhandari, P.: Regional differentials in multidimensional poverty in Nepal: rethinking dimensions and method of computation. SAGE Open 9, 1–18 (2019)

Greco, S., Ishizaka, A., Resce, G., Torrisi, G.: Measuring well-being by a multidimensional spatial model in OECD Better Life Index framework. Socioecond. Plann. Sci. 70, 100684 (2019)

Hick, R.: Poverty as capability deprivation: conceptualizing and measuring poverty in contemporary Europe. Eur. J. Sociol. 55(3), 295–323 (2014)

Higgins, J.P.T., Green, S.: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (Updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration (2011). Available from: http://handbook.cochrane.org/

Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A.: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, version 6.1 (updated September 2020). Cochrane (2020). Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

Iglesias, K., Suter, C., Beycan, T., Vani, B.P.: Exploring multidimensional well-being in Switzerland: comparing three synthesizing approaches. Soc. Indic. Res. 134, 847–875 (2017)

Kana Zeumo, V., Tsoukiàs, A., Somé, B.: A new methodology for multidimensional poverty measurement based on the capability approach. Socioecond. Plann. Sci. 48(4), 273–289 (2014)

Kana Zeumo V, Somé B, Tsoukiàs A (2011) A survey on multidimensional poverty measurement: a decision aiding perspective. Hal-00875525

Li, G., Cai, Z., Liu, J., Liu, X., Su, S., Huang, X., Bozhao, L.: Multidimensional poverty in rural China: indicators, spatiotemporal patterns and applications. Soc. Indic. Res. 144, 1099–1134 (2019)

Lister, R.: Poverty: Key Concepts. Polity Press, Cambridge (2004)

Mitra, S., Jones, K., Vick, B., Brown, D., McGinn, E., Alexander, M.J.: Implementing a multidimensional poverty measure using mixed methods and a participatory framework. Soc. Indic. Res. 110, 1061–1081 (2013)

Mohamed Shaffril, H.A., Samsuddin, S.F., Abu Samah, A.: The ABC of systematic literature review: the basic methodological guidance for beginners. Qual. Quant. 55, 1319–1346 (2021)

Moonansingh, C.A., Wallace, W.C., Dialsingh, I.: From unidimensional to multidimensional measurement of poverty in Trinidad and Tobago: the latent class analysis of poverty measurement as an alternative to the financial deprivation model. Poverty Public Policy 11(1–2), 57–72 (2019)

Mulrow, C.D.: Systematic reviews—rationale for systematic reviews. BMJ 309(6954), 597–599 (1994)

Nicholas, A., Ray, R., Sinha, K.: Differentiating between dimensionality and duration in multidimensional measures of poverty: methodology with an application to China. Rev. Income Wealth 65, 48–74 (2019)

Nowak, D., Scheicher, C.: Considering the extremely poor: multidimensional poverty measurement for Germany. Soc. Indic. Res. 133, 139–162 (2017)

Peichl, A., Pestel, N.: Multidimensional affluence: theory and applications to Germany and the US. Appl. Econ. 45(32), 4591–4601 (2013)

Petrillo, I.: Computation of equivalent incomes and social welfare for EU and non-EU countries. Cesifo Econ. Stud. 64(3), 396–425 (2018)

Pinar, M.: Multidimensional well-being and inequality across the European regions with alternative interactions between the well-being dimensions. Soc. Indic. Res. 144, 31–72 (2019)

Rodero-Cosano, M.L., Garcia-Alonso, C.R., Salinas-Pérez, J.A.: A deprivation analysis for Andalusia (Spain): an approach based on structural equations. Soc. Indic. Res. 115(2), 751–765 (2014)

Sen, A.: Commodities and Capabilities. North-Holland Publishing, Amsterdam (1985)

Tranfield, D., Denyer, D., Smart, P.: Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 14, 207–222 (2003)

Uman, L.U.: Systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J. Can. Acad. Child Adoles. Psychiatry 20(1), 57–59 (2011)

Vivas, C., Barge-Gil, A.: Impact on firms of the use of knowledge external sources: a systematic review of the literature. J. Econ. Surv. 29(5), 943–964 (2015)

World Bank: Attacking Poverty: World Development Report 2000/2001. OUP, Oxford (2001)

Funding

Open access funding provided by Alma Mater Studiorum - Università di Bologna within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. The authors have not disclosed any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 List of articles from the literature review

Abraham, R.A. and Kumar, K.S.K. (2008) Multidimensional poverty and vulnerability. Economic and Political Weekly 43(20):77, 79-87.

Adepoju, A.O. and Akinluyi, O.I. (2017) Multidimensional poverty status of rural households in Nigeria: Does family planning have any effect?. International Journal of Social Economics 44(8): 1046-1061.

Alkire, S., Apablaza, M., Chakravarty, S. and Yalonetzky, G. (2017) Measuring chronic multidimensional poverty. Journal of Policy Modeling 39(6): 983-1006.

Alkire, S. and Fang, Y. (2019) Dynamics of multidimensional poverty and uni-dimensional income poverty: An evidence of stability analysis from China. Social Indicators Research 142: 25-64.

Alkire, S. and Foster, J. (2011) Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement. Journal of Public Economics 95: 476-487.

Alkire, S., Jindra, C., Aguilar, G.R. and Vaz, A. (2017) Multidimensional poverty reduction among countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Forum for Social Economics 46(2): 178-191.

Alkire, S., Roche, J.M., Seth, S. and Sumner, A. (2015) Identifying the poorest people and groups: Strategies using the global multidimensional poverty index. Journal of International Development 27: 362-387.

Alkire, S., Roche, J.M. and Vaz, A. (2017) Changes over time in multidimensional poverty: Methodology and results for 34 countries. World Development 94: 232-249.

Alkire, S. and Santos, M.E. (2014) Measuring acute poverty in the developing world: Robustness and scope of the multidimensional poverty index. World Development 59: 251-274.

Alkire, S. and Seth, S. (2013) Selecting a targeting method to identify BPL households in India. Social Indicators Research 112: 417-446.

Alkire, S. and Seth, S. (2015) Multidimensional poverty reduction in India between 1999 and 2006: Where and how?. World Development 72: 93-108.

Altamirano Montoya, Á.J. and Teixeira, K.M.D. (2017). Multidimensional poverty in Nicaragua: Are female-headed households better off?. Social Indicators Research 132: 1037-1063.

Angulo, R., Díaz, Y. and Pardo, R. (2016) The Colombian multidimensional poverty index: Measuring poverty in a public policy context. Social Indicators Research 127: 1-38.

Annoni, P. and Weziak-Bialowolska, D. (2016) A Measure to target antipoverty policies in the European Union regions. Applied Research in Quality of Life 11: 181-207.

Annoni, P., Bruggemann, R. and Carlsen, L. (2015) A multidimensional view on poverty in the European Union by partial order theory. Journal of Applied Statistics 42(3): 535-554.

Antoniades, A., Widiarto, I. and Antonarakis, A.S. (2019) Financial crises and the attainment of the SDGs: An adjusted multidimensional poverty approach. Sustainability Science (published online: 28 December 2019).

Aristei, D. and Perugini, C. (2010) Preferences for redistribution and inequality in well-being across Europe. Journal of Policy Modeling 32(2): 176-195.

Arndt, C., Hussain, A. M., Salvucci, V., Tarp, F. and Østerdal, L. P. (2016) Poverty mapping based on first-order dominance with an example from Mozambique. Journal of International Development 28: 3-21.

Arndt, C., Mahrt, K., Hussain, M.A. and Tarp, F. (2018) A human rights-consistent approach to multidimensional welfare measurement applied to sub-Saharan Africa. World Development 108: 181-196.

Artha, D.R., and Dartanto, T. (2018) The multidimensional approach to poverty measurement in Indonesia: Measurements, determinants and its policy implications. Journal of Economic Cooperation and Development 39: 1-38.

Ashaal, A. and Bakri, A. (2019) A multidimensional poverty analysis: Evidence from Lebanese data. International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering 7(6S5): 2277-3878.

Awan, M.S., Waqas, M. and Aslam, M.A. (2015) Multidimensional measurement of poverty in Pakistan: Provincial analysis. Nóesis. Revista de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades 24: 54-71.

Ayala, L., Jurado, A. and Pérez-Mayo, J. (2011) Income poverty and multidimensional deprivation: Lessons from cross-regional analysis. Review of Income and Wealth 57: 40-60.

Ayoola Oni, O. and Adenike Adepoju, T. (2014) Analysis of rural households’ wellbeing in Nigeria: A capability approach. International Journal of Social Economics 41(9): 760-779.

Bader, C., Bieri, S., Wiesmann, U. and Heinimann, A. (2016a) Differences between monetary and multidimensional poverty in the Lao PDR: Implications for targeting of poverty reduction policies and interventions. Poverty & Public Policy 8: 171-197.

Bader, C., Bieri, S., Wiesmann, U. and Heinimann, A. (2016b) Different perspective on poverty in Lao PDR: Multidimensional poverty in Lao PDR for the years 2002/2003 and 2007/2008. Social Indicators Research 126: 483-502.

Bader, C., Bieri, S., Wiesmann, U. and Heinimann, A. (2017) Is economic growth increasing disparities? A multidimensional analysis of poverty in the Lao PDR between 2003 and 2013. The Journal of Development Studies, 53(12): 2067-2085.

Ballon, P. and Duclos, J.-Y. (2016) A Comparative analysis of multidimensional poverty in Sudan and South Sudan. African Development Review 28: 132-161.

Banerjee, A.K. (2010) A multidimensional Gini index. Mathematical Social Sciences 60(2): 87-93.

Banerjee, A.K. (2018) Normative properties of multidimensional inequality indices with data-driven dimensional weights: The case of a Gini index. International Journal of Economic Theory 14: 279-288.

Bangun, W. (2019) Multidimensional poverty index (MPI): A study in Indonesian on ASEAN. International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering 8(1S): 207-212.

Basarir, H. (2011) Poor, multidimensionally speaking: Evidence from South Africa. Journal of African Economies 20(3): 463-504.

Batana, Y.M. (2010) Aid and poverty in Africa: Do well-being measures understate the progress?. African Development Review 22: 452-469.

Battiston, D., Cruces, G., Lopez-Calva, L.F., Lugo, M.A. and Santos, M. E. (2013) Income and beyond: Multidimensional poverty in six Latin American countries. Social Indicators Research 112: 291-314.

Bautista, C.C. (2018) Explaining multidimensional poverty: A household-level analysis. Asian Economic Papers 17(3): 183-210.

Belhadj, B. (2011a) A new fuzzy unidimensional poverty index from an information theory perspective. Empirical Economics 40: 687-704.

Belhadj, B. (2011b) New fuzzy indices of poverty by distinguishing three levels of poverty. Research in Economics 65(3): 221-231.

Belhadj, B. (2012) New weighting scheme for the dimensions in multidimensional poverty indices. Economics Letters 116(3): 304-307.

Belhadj, B. (2013) New fuzzy indices for multidimensional poverty. Journal of Intelligent & Fuzzy Systems 24(3): 587-591.

Belhadj, B. and Limam, M. (2012) Unidimensional and multidimensional fuzzy poverty measures: New approach. Economic Modelling 29(4): 995-1002.

Bellani, L. (2013) Multidimensional indices of deprivation: The introduction of reference groups weights. The Journal of Economic Inequality 11: 495-515.

Bennett, C.J. and Mitra, S. (2013) Multidimensional poverty: Measurement, estimation, and inference. Econometric Reviews 32(1): 57-83.

Bérenger, V. (2017) Using ordinal variables to measure multidimensional poverty in Egypt and Jordan. The Journal of Economic Inequality 15: 143-173.

Bérenger, V. (2019) The counting approach to multidimensional poverty: The case of four African countries. South African Journal of Economics 87(2): 200-227.

Bérenger, V. and Celestini, F. (2006) Is there a clearly identifiable distribution function of individual poverty scores?. Journal of Income Distribution 15(3-4): 55-77.

Bérenger, V., Deutsch, J. and Silber, J. (2013) Durable goods, access to services and the derivation of an asset index: Comparing two methodologies and three countries. Economic Modelling 35: 881-891.

Betti, G., D’Agostino, A. and Neri, L. (2002) Panel regression models for measuring multidimensional poverty dynamics. Statistical Methods & Applications 11: 359–369.

Betti, G., Gagliardi, F., Lemmi, A. and Verma, V. (2015) Comparative measures of multidimensional deprivation in the European Union. Empirical Economics 49: 1071–1100.

Betti, G., Gagliardi, F. and Verma, V. (2018) Simplified jackknife variance estimates for fuzzy measures of multidimensional poverty. International Statistical Review 86: 68-86.

Bibi, S. and El Lahga, A.R. (2008) Robust ordinal comparisons of multidimensional poverty between South Africa and Egypt. Revue d'Économie du Développement 16(5): 37-65.

Bosmans, K., Decancq, K. and Ooghe, E. (2015) What do normative indices of multidimensional inequality really measure?. Journal of Public Economics 30: 94-104.

Bosmans, K., Lauwers, L. and Ooghe, E. (2018) Prioritarian poverty comparisons with cardinal and ordinal attributes. Scandinavian Journal of Economics 120: 925-942.

Bossert, W., Chakravarty, S.R. and D'Ambrosio, C. (2013) Multidimensional poverty and material deprivation with discrete data. Review of Income and Wealth 59: 29-43.

Bucheli, J.R., Bohara, A.K. and Villa, K. (2018) Paths to development? Rural roads and multidimensional poverty in the hills and plains of Nepal. Journal of International Development 30: 430-456.

Callander, E.J., Schofield, D.J. and Shrestha, R.N. (2012) Capacity for freedom – using a new poverty measure to look at regional differences in living standards within Australia. Geographical Research 50: 411-420.

Calvo, C. (2008) Vulnerability to multidimensional poverty: Peru, 1998–2002. World Development 36(6): 1011-1020.

Castro, J.F, Baca, J. and Ocampo, J.P. (2012) (Re)counting the poor in Peru: A multidimensional approach. Latin American Journal of Economics 49(1): 37-65.

Cavapozzi, D., Han, W. and Miniaci, R. (2015) Alternative weighting structures for multidimensional poverty assessment. The Journal of Economic Inequality 13: 425-447.

Chakravarty, S.R., Deutsch, J. and Silber, J. (2008) On the Watts multidimensional poverty index and its decomposition. World Development 36(6): 1067-1077.

Chowdhury, T.A. and Mukhopadhaya, P. (2012) Assessment of multidimensional poverty and effectiveness of microfinance-driven government and NGO projects in the rural Bangladesh. The Journal of Socio-Economics 41(5): 500-512.

Chowdhury, T.A. and Mukhopadhaya, P. (2014) Multidimensional poverty approach and development of poverty indicators: The case of Bangladesh. Contemporary South Asia 22(3): 268-289.

Ciani M., Gagliardi F., Riccarelli S. and Betti G. (2019) Fuzzy measures of multidimensional poverty in the Mediterranean area: A focus on financial dimension. Sustainability 11(1):143.

Ciommi, M., Gentili, A., Ermini, B., Gigliarano, C., Chelli, F.M., and Gallegati, M. (2017) Have your cake and eat it too: The well-being of the Italians (1861–2011). Social Indicators Research 134: 473-509

Ciommi, M., Gigliarano, C., Emili, A., Taralli, S. and Chelli, F.M. (2017) A new class of composite indicators for measuring well-being at the local level: An application to the equitable and sustainable well-being (BES) of the Italian provinces. Ecological Indicators 76: 281-296.

Coromaldi, M. and Zoli, M. (2012) Deriving multidimensional poverty indicators: Methodological issues and an empirical analysis for Italy. Social Indicators Research 107(37): 37-54.

Croci Angelini, E. and Michelangeli, A. (2012) Axiomatic measurement of multidimensional well-being inequality: Some distributional questions. The Journal of Socio-Economics 41(5): 548-557.

Cuenca García, E., Navarro Pabsdorf, M. and Moran Alvarez J.C. (2019) Factors determining differences in the poverty degree among countries. Resources 8(3): 122.

de Silva, A.F., de Sousa, J.S. and Araujo, J.A. (2017) Evidences on multidimensional poverty in the Northern Region of Brazil. Revista de Administração Pública 51(2): 219-239.

Datt, G. (2019a) Distribution-sensitive multidimensional poverty measure. World Bank Economic Review 33(3): 551-572.

Datt, G. (2019b) Multidimensional poverty in the Philippines, 2004–2013: How much do choices for weighting, identification and aggregation matter?. Empirical Economics 57: 1103–1128.

Dawson, N.M. (2018) Leaving no-one behind? Social inequalities and contrasting development impacts in rural Rwanda. Development Studies Research 5(1): 1-14.

De Rosa, D. (2018) Capability approach and multidimensional well-being: The Italian case of BES. Social Indicators Research 140: 125-155.

Decancq, K. (2017) Measuring multidimensional inequality in the OECD member countries with a distribution-sensitive Better Life Index. Social Indicators Research 131: 1057-1086.

Decancq, K., Decoster, A. and Schokkaert, E. (2009) The evolution of world inequality in well-being. World Development 37(1): 11-25.

Decancq, K., Fleurbaey, M. and Maniquet, F. (2019) Multidimensional poverty measurement with individual preferences. The Journal of Economic Inequality 17: 29-49.

Decancq, K., Fleurbaey, M. and Schokkaert, E. (2017) Wellbeing inequality and preference heterogeneity. Economica 84: 210-238.

Decancq, K. and Lugo, M.A. (2012) Inequality of wellbeing: A multidimensional approach. Economica 79: 721-746.

Decancq, K., Van Ootegem, L. and Verhofstadt, E. (2013) What if we voted on the weights of a multidimensional well-being index? An illustration with Flemish data. Fiscal Studies 34(3): 315-332.

Dehury B. and Mohanty, S.K. (2015) Regional estimates of multidimensional poverty in India. Economics: The Open-Access, Open-Assessment E-Journal 9 (36): 1-35.

Dehury, B., Mohanty, S.K. (2017) Multidimensional poverty, household environment and short-term morbidity in India. Genus 73: 3.

Delalić, A. (2012) Multidimensional aspects of poverty in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 25(1): 174-183.

Deutsch, J. and Silber, J. (2005) Measuring multidimensional poverty: An empirical comparison of various approaches. Review of Income and Wealth 51: 145-174.

Dewilde, C. (2004) The multidimensional measurement of poverty in Belgium and Britain: A categorical approach. Social Indicators Research 68: 331-369.

Dewilde, C. (2008) Individual and institutional determinants of multidimensional poverty: A European comparison. Social Indicators Research 86: 233-256.

Di Martino, S., Di Napoli, I., Esposito, C., Prilleltensky, I. and Arcidiacono, C. (2018) Measuring subjective well-being from a multidimensional and temporal perspective: Italian adaptation of the I COPPE scale. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 16(1): 88.

Djossou, G.N., Kane, G.Q. and Novignon, J. (2017) Is growth pro-poor in Benin? Evidence using a multidimensional measure of poverty. Poverty & Public Policy 9: 426-443.

Döpke, J., Knabe, A., Lang, C. and Maschke, P. (2017) Multidimensional well-being and regional disparities in Europe. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 55: 1026-1044.

dos Santos, E.I., de Carvalho, I.C.S. and Sá Barreto, R.C (2017) Multidimensional poverty in the state of Bahia: A spatial analysis from the censuses of 2000 and 2010. Revista de Administração Pública 51(2): 240-263.

Duclos, J.-Y., Sahn, D.E. and Younger, S.D. (2011) Partial multidimensional inequality orderings. Journal of Public Economics 95(3-4): 225-238.

Duclos, J.-Y., Tiberti, L. and Araar, A. (2018) Multidimensional poverty targeting. Economic Development and Cultural Change 66(3): 519-554.

Durand, M. (2015) The OECD Better Life initiative: How's Life? and the measurement of well-being. Review of Income and Wealth 61: 4-17.

Eberharter V.V. (2018) Capability deprivation, and the intergenerational transmission of social disadvantages - empirical evidence from selected countries. Social Sciences 7(12): 253.

El Bouhadi, A., Elkhider, A. and Kchirid, E.M. (2012) The multidimensional approach poverty measurement: Case of Morocco. Applied Econometrics and International Development 12(2): 135-150.

Ele‐Ojo Ataguba, J., Eme Ichoku, H. and Fonta, W.M. (2013) Multidimensional poverty assessment: Applying the capability approach. International Journal of Social Economics 40(4): 331-354.

Ervin, P.A., Gayoso de Ervin, L., Molinas Vega, J.R. and Sacco, F.G. (2018) Multidimensional poverty in Paraguay: Trends from 2000 to 2015. Social Indicators Research 140(3): 1035-1076.

Espinoza-Delgado, J. and Klasen, S. (2018). Gender and multidimensional poverty in Nicaragua: An individual based approach. World Development 110: 466-491.

Espinoza-Delgado, J. and López-Laborda, J. (2017) Nicaragua: trend of multidimensional poverty, 2001-2009. CEPAL Review 121: 31-51.

Esposito, L. and Chiappero-Martinetti, E. (2010) Multidimensional poverty: Restricted and unrestricted hierarchy among poverty dimensions. Journal of Applied Economics 13(2): 181-204.

Esposito, L. and Chiappero-Martinetti, E. (2019) Eliciting, applying and exploring multidimensional welfare weights: Evidence from the field. Review of Income and Wealth 65: S204-S227.

Fahel, M. and Ribeiro Teles, L. (2018) Measuring multidimensional poverty in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil: Looking beyond income. Revista de Administração Pública 52(3): 386-416.

Fransman T. and Yu, D. (2019) Multidimensional poverty in South Africa in 2001-16. Development Southern Africa 36(1): 50-79.

Gajdos, T. and Weymark, J.A. (2005) Multidimensional generalized Gini indices. Economic Theory 26(3): 471-496.

Gallardo, M. (2019) Measuring vulnerability to multidimensional poverty. Social Indicators Research (published online: 19 September 2019)

Gao, Q., Yang, S., Zhang, Y. and Li, S. (2018) The divided Chinese welfare system: Do health and education change the picture?. Social Policy and Society 17(2): 1-18.

Garcia-Diaz, R. and Prudencio, D. (2017) A Shapley decomposition of multidimensional chronic poverty in Argentina. Bulletin of Economic Research 69: 23-41.

García-Pérez, C., González-González, Y. and Prieto-Alaiz, M. (2017) Identifying the multidimensional poor in developed countries using relative thresholds: An application to Spanish data. Social Indicators Research 131: 291–303.

Gasparini, L., Sosa-Escudero, W., Marchionni, M. and Olivieri, S. (2013) Multidimensional poverty in Latin America and the Caribbean: New evidence from the Gallup World Poll. The Journal of Economic Inequality 11: 195-214.

Gigliarano, C. and Mosler, K. (2009) Constructing indices of multivariate polarization. The Journal of Economic Inequality 7: 435.

Golgher, A. (2015) Multidimensional poverty in urban Brazil: Income, assets and expenses. International Journal of Social Economics 43(1): 19-38.

Goli, S., Maurya, N.K., Moradhvaj and Bhandari, P. (2019) Regional differentials in multidimensional poverty in Nepal: Rethinking dimensions and method of computation. SAGE Open 1-18.

Greco, S., Ishizaka, A., Resce, G. and Torrisi, G. (2019) Measuring well-being by a multidimensional spatial model in OECD Better Life Index framework. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences 70:100684.

Grosse, M., Harttgen, K. and Klasen, S. (2008) Measuring pro-poor growth in non-income dimensions. World Development 36(6): 1021-1047.

Guo, Y., Zhou, Y. and Cao, Z. (2018) Geographical patterns and anti-poverty targeting post-2020 in China. Journal of Geographical Sciences 28(12): 1810-1824.

Hanandita, W. and Tampubolon, G. (2016) Multidimensional poverty in Indonesia: Trend over the last decade (2003–2013). Social Indicators Research 128: 559-587.

Haq, R. and Zia, U. (2013) Multidimensional wellbeing: An index of quality of life in a developing economy. Social Indicators Research 114: 997-1012.

Hasan, H. and Ali, S.S. (2018) Measuring deprivation from Maqāṣid al-Sharīʿah dimensions in OIC countries: Ranking and policy focus. Journal of King Abdulaziz University: Islamic Economics 31(1): 3-26.

Hick, R. (2016) The coupling of disadvantages: Material poverty and multiple deprivation in Europe before and after the great recession. European Journal of Social Security 18(1): 2-29.

Hlasny, V. and AlAzzawi, S. (2019) Asset inequality in the MENA: The missing dimension?. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 73: 44-55.

Hull, J.R. and Guedes, G. (2013) Rebuilding Babel: Finding common development solutions using cross-contextual comparisons of multidimensional well-being. Revista Brasileira de Estudos de Populacao 30(1): 271-297.

Hussain, M.A. (2016) EU country rankings’ sensitivity to the choice of welfare indicators. Social Indicators Research 125: 1-17.

Idrees, M. and Baig, M. (2017) An empirical analysis of multidimensional poverty in Pakistan. FWU Journal of Social Sciences 11(1): 297-309.

Iglesias, K., Suter, C., Beycan, T. and Vani, B.P. (2017) Exploring multidimensional well-being in Switzerland: Comparing three synthesizing approaches. Social Indicators Research 134: 847–875.

Ismail, M.K., Siwar, C. and Ghazali, R. (2018) Gahai agropolitan project in eradicating poverty: Multidimensional poverty index. Planning Malaysia: Journal of the Malaysian Institute of Planners 16(3): 97-108.

Ivaldi, E., Bonatti, G. and Soliani, R. (2016) The construction of a synthetic index comparing multidimensional well-being in the European Union. Social Indicators Research 125: 397-430.

Jamal, H. (2011) Assessing poverty with non-income deprivation indicators: Pakistan, 2008-09. The Pakistan Development Review 50(4): 913-927.

Jamal, H. (2016) Spatial disparities in socioeconomic development: The case of Pakistan. The Pakistan Development Review 55(4): 421-435.

Jindra, C. and Vaz, A. (2019) Good governance and multidimensional poverty: A comparative analysis of 71 countries. Governance 32: 657-675.

Jung, H.-S., Kim, S.-W. and Ahn, S.-H. (2014) Multidimensional inequality in South Korea: An empirical analysis. Asian Social Work and Policy Review 8(2): 170-191.

Jurado, A. and Perez-Mayo, J. (2012) Construction and evolution of a multidimensional well-being index for the Spanish regions. Social Indicators Research 107: 259-279.

Justino, P. (2011) Multidimensional welfare distributions: Empirical application to household panel data from Vietnam. Applied Economics 44(26): 3391-3405.

Kana Zeumo, V., Tsoukiàs, A. and Somé, B. (2014) A new methodology for multidimensional poverty measurement based on the capability approach. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences 48(4): 273-289.

Khalid, M.W., Zahid, J., Ahad, M., Shah, A.H. and Ashfaq, F. (2019) Dynamics of unidimensional and multidimensional inequality in Pakistan: Evidence from regional and provincial level study. International Journal of Social Economics 46(2): 170-181.

Khan, A.U., Saboor, A., Mian, S.A. and Malik, I.A. (2011) Approximation of multidimensional poverty across regions in Pakistan. European Journal of Social Sciences 24(2): 226-236.

Khan, A., Saboor, A., Ali, I., Malik, W. and Mahmood, K. (2016). Urbanization of multidimensional poverty: Empirical evidences from Pakistan. Quality & Quantity 50(1): 439-469.

Kim, S.G. (2016) What have we called as “poverty”? A multidimensional and longitudinal perspective. Social Indicators Research 129: 229-276.

Kobus, M., Kurek, R. (2019) Multidimensional polarization for ordinal data. The Journal of Economic Inequality 17: 301-317.

Kpoor, A. (2019) Assets and livelihoods of male- and female-headed households in Ghana. Journal of Family Issues 40(18): 2974-2996.

Krishnakumar, J. and Nogales, R. (2019). Public policies and equality of opportunity for wellbeing in multiple dimensions: A theoretical discussion and evidence from Bolivia. Social Indicators Research (published online: 18 December 2019).

Labar, K. and Bresson, F. (2011) A multidimensional analysis of poverty in China from 1991 to 2006.China Economic Review 22(4): 646-668.

Larru, J.M. (2017) Linking ODA to the MPI: A proposal for Latin America. Global Economy Journal 17(3): 20170041.