Abstract

Biological sulfate reduction can be used for the removal and recovery of oxidized sulfur compounds and metals from waste streams. However, the costs of conventional electron donors, like hydrogen and ethanol, limit the application possibilities. Methane from natural gas or biogas would be a more attractive electron donor. Sulfate reduction with methane as electron donor prevails in marine sediments. Recently, several authors succeeded in cultivating the responsible microorganisms in vitro. In addition, the process has been studied in bioreactors. These studies have opened up the possibility to use methane as electron donor for sulfate reduction in wastewater and gas treatment. However, the obtained growth rates of the responsible microorganisms are extremely low, which would be a major limitation for applications. Therefore, further research should focus on novel cultivation techniques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Carbon and sulfur cycling in nature

1.1 Physical and chemical properties of methane

Methane (CH4) is a tetrahedral shaped molecule, and a colorless, nontoxic and odorless gas (above 109°K at 1 atm). CH4 gas is only flammable when the concentration in the air is between 5 and 15%. It has a relatively low solubility product in water (1.44 mM in distillated water at 20°C and 0.101 MPa CH4; Yamamoto et al. 1967). About 2.7 million years ago, CH4 was a major component in the earth’s atmosphere (Chang et al. 1983). Since then, the atmosphere became more oxidized. In 1998, the average atmospheric CH4 concentration was 1.7 ppm (Houghton et al. 2001). CH4 is the simplest and most stable hydrocarbon. Compared with other alkanes, CH4 has a high C–H bond strength, making it chemically rather stable. The dissociation energy of the C–H bond in CH4 is +439 kJ mol−1 (Thauer and Shima 2008). CH4 is the least reactive alkane in reactions involving hydride abstraction by an electrophile, because the C–H bond is not polarized (Crabtree 1995). Therefore, CH4 is only a good substrate for specialized microorganisms.

CH4 is the most reduced form of carbon (oxidation state −4), carbon dioxide (CO2) being the most oxidized form (oxidation state +4). CH4 is the main component of natural gas (70–90%) and biogas (50–70%). The energy yield per carbon during oxidation is for CH4 higher than for other hydrocarbons or coal. Therefore, less CO2 is produced per kWatt during the complete oxidation of CH4.

1.2 Methane production

Biogas, with CH4 as the major reduced component, is produced during the biological degradation of organic matter when respiration is not possible. In the presence of inorganic electron acceptors like oxygen, nitrate, iron (III), manganese (IV) and sulfate, microorganisms oxidize organic compounds completely to CO2. During these respiratory processes, microorganisms conserve energy for their metabolism. The reduction of oxygen is most favorable and the reduction of CO2 to CH4 is the least favorable. Sulfate reduction (SR) is only slightly more favorable than CO2 reduction. Organic matter degradation will, in general, only result in CH4 production when inorganic electron accepters are depleted.

Methanogenesis occurs in marine and freshwater sediments that are rich in organic matter, in wetlands and in the intestinal tract of insects (e.g. termites). Engineered methanogenic systems, e.g. digesters, upflow anaerobic sludge bed (UASB) and expanded granular sludge bed (EGSB) reactors, are widely applied for the treatment solid wastes and waste waters rich in organic matter. Such waste streams are produced in agriculture, households, the food and beverage industry and the paper industry (Frankin 2001). The produced biogas is recovered and can be used as fuel (Lettinga and van Haandel 1993). Anthropogenic CH4 emissions arise from agriculture and waste disposal, including enteric fermentation, animal and human wastes, rice paddies, biomass burning and landfills.

Methanogenic degradation of organic matter proceeds via a number of microbial processes; during hydrolyses, acidogenesis and acetogenesis complex organic matter is degraded to hydrogen and CO2, formate, acetate and ammonium (Fig. 1; Harper and Pohland 1986; Stams 1994; Muyzer and Stams 2008). The final step is methanogenesis. Methanogens are strict anaerobes and belong to the archaea. Three methanogenic pathways can be distinguished: the hydrogenotrophic pathway, in which hydrogen and CO2, formate or carbon monoxide (Daniels et al. 1977; O’Brien et al. 1984) are utilized for CH4 production; the aceticlastic pathway, in which acetate is converted to CH4 and CO2; and the methylotrophic pathway, in which methanol or other methylated compounds (methanethiol, dimethyl sulfide, or methylated amines) are partly oxidized and partly converted to CH4 (Deppenmeier et al. 1996). Some methanogens are able to use pyruvate as carbon and energy source and some are able to utilize ethanol or isopropanol as electron donor for CO2 reduction (Stams 1994).

1.3 Sulfate reduction

Dissimilatory sulfate reduction is the reduction of sulfate to sulfide to obtain energy for growth and maintenance. This metabolic feature is exclusively done by sulfate-reducing microorganisms (SRB). SRB are a diverse group of prokaryotes (Castro et al. 2000), the known SRB can be grouped into seven phylogenetic lineages, five within the bacteria and two within the archaea (Muyzer and Stams 2008). Typically SRB occur in anoxic marine and freshwater environments (Postgate 1984). Eight electrons are needed for the reduction of one sulfate to one sulfide. The reduction equivalents are obtained by the oxidation of organic compounds or hydrogen. The different SRB are able to utilize a wide range of organic electron donors, including ethanol, formate, lactate, pyruvate, fatty acids, carbon monoxide, methanol, methanethiol and sugars (Fig. 1; Widdel et al. 2007; Muyzer and Stams 2008). SRB have a higher affinity for hydrogen than methanogens, and therefore outcompete methanogens at low hydrogen partial pressures. It has often been observed that acetate is predominately degraded by methanogens in presence of sulfate though (van Bodegom and Stams 1999; Stams et al. 2005). Acetate-degrading sulfate reducers have only slightly better growth kinetic properties than Methanosaeta (dominant in anaerobic sludge). Therefore it may take years before aceticlastic methanogens are outcompeted by acetate-degrading sulfate reducers, especially when the relative cell number of the acetate-degrading sulfate reducers is initially low (Stams et al. 2005).

SR only occurs when electron acceptors with a higher redox potential (e.g. oxygen and nitrate) are absent. These sulfate-reducing conditions are found in sediments and stratified waters, in which the penetration of oxygen is limited. Sulfide produced in the anoxic compartment will be partly transported to the aerobic compartment where sulfide is oxidized to sulfate, and visa versa (Bottrell and Newton 2006; Holmer and Storkholm 2001). SR and sulfide oxidation form the main routes of the biological sulfur cycle (Fig. 2).

1.4 Sources of methane in marine sediments

Seawater contains ~28 mM sulfate. Therefore organic matter oxidation in marine sediments is for a large part coupled to SR. However, when the organic matter input is large enough, sulfate will be depleted in the top part of the sediment and organic matter degradation will result in CH4 production. The highest marine CH4 production rates can be found near the continental margins, because the primary production in the overlying surface waters and thus also the organic matter deposition is largest in those relatively shallow waters. This CH4 production by organic matter degradation is a very diffuse source for CH4.

There are also some less diffuse sites where CH4 is passing up by convection along cracks and faults. These are called cold seeps or CH4 vents, in which pore water or fluid with dissolved CH4 seeps up from deeper sediment layers, or in which gaseous CH4 vents up. This results in ecological niches with large CH4 inputs. These seeps can occur in many forms, e.g. as mud volcano’s (Damm and Budéus 2003; Stadnitskaia et al. 2006) or brine pools. In addition to cold seeps and vents there are hydrothermal vents where mainly CH4 is being vented (Boetius 2005). These are different from the “black smokers”, in which mainly sulfide is vented.

The CH4 from these vents and seeps can be produced biologically, but can also be produced geochemically or thermogenically from organic matter (Sibuet and Olu 1998). CH4 seeps and vents occur above fossil fuel fields or gas hydrates. Gas hydrates are ice-like structures in which a gas, mostly CH4, is incorporated. The earth’s gas hydrates contain more energy than all other known oil, natural gas and coal reservoirs combined (Kvenvolden 1995). These hydrates are stable at low temperatures (<15°C), high pressures (>5.0 MPa) and in the presence of dissolved CH4 (Sultan et al. 2003), but the hydrates will dissociate when they come in contact with warm fluids or when dissolved CH4 is depleted (Boetius and Suess 2004).

1.5 Aerobic methane oxidation

Aerobic methanotrophs are bacteria that use CH4 as electron donor and carbon source (Anthony 1982; Amaral and Knowles 1995). Aerobic methanotrophs are found in samples from muds, swamps, rivers, rice paddies, oceans, ponds, soils from meadows, deciduous woods and sewage sludge (Hanson and Hanson 1996). The aerobic CH4 oxidation (reaction 1) occurs via a linear pathway, in which CH4 is first converted to methanol by a NADH-dependent monooxygenase. Methanol is further oxidized via formaldehyde and formate to carbon dioxide by NADH-independent methanol dehydrogenase, formaldehyde dehydrogenase and formate dehydrogenase. The electrons released in these steps are passed to the electron transport chain for adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis (Hanson and Hanson 1996).

Under oxygen limiting conditions, methanotrophs can produce methanol (Xin et al. 2004; Lee et al. 2004) or acetate (Costa et al. 2000) from CH4. Denitrifiers are able to utilize these products. In this way, denitrification with CH4 as electron donor is possible at oxygen limiting conditions (Costa et al. 2000; Waki et al. 2004). A similar process for SR has thus far not been described, although some sulfate reducers can tolerate the presence of oxygen (Muyzer and Stams 2008).

1.6 Anaerobic oxidation of methane

For many years anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM) was thought to be impossible (Thauer and Shima 2008). In the 70s of the last century evidence for the occurrence of AOM was obtained during geochemical in situ studies in anaerobic marine sediments and waters. CH4 diffusing upwards from deeper sediment layers was oxidized before reaching oxic zones. The consumption of CH4 was assumed to be coupled to the consumption of sulfate, diffusing downward from the seafloor (Fig. 3; Martens and Berner 1974, 1977; Barnes and Goldberg 1976; Reeburgh 1976; Alperin and Reeburgh 1985). Radioisotope tracer experiments with 14C-labeled CH4 and 35S-labeled sulfate, showed a maximum AOM and SR rate at the methane sulfate transition zone (Reeburgh 1980; Iversen and Jørgensen 1985; Iversen et al. 1987; Alperin 1989; Reeburgh et al. 1991; Joye et al. 1999). In addition, at the sulfate to methane transition zone shifts in the isotopic composition (13C and 12C content) of CH4, which was heavier above the transition zone, and inorganic carbon, which was lighter above the transition zone, were found (Oremland and DesMarais 1983; Whiticar 1996; Oremland et al. 1987; Alperin et al. 1988; Blair and Aller 1995; Martens et al. 1999). These studies showed a stoichiometry according to reaction 2.

The bicarbonate and alkalinity production by AOM has resulted in the formation of chimney-like structures from calcium carbonate above CH4 vents (Michaelis et al. 2002; Stadnitskaia et al. 2005). These CH4 seeps or vents can also drive chemotropic ecosystems. The sulfide produced by AOM is, at least partly, transported upwards and aerobically oxidized to sulfur or sulfate, e.g. in tube worms or in microbial mats of Beggiatoa.

The AOM rate depends on a variety of conditions including the organic content of the sediment, CH4 supply rate, sulfate penetration in the sediment, temperature and pressure (Valentine 2002). Because of the higher supply rates, the AOM rates at CH4 seeps and vents are higher than in sediments where CH4 is just supplied by organic matter degradation (Table 1).

AOM has also been observed in non-marine environments. Iversen et al. (1987), Panganiban et al. (1979) and Eller et al. (2005) observed AOM in lakes and Grossman et al. (2002) in a landfill. In these cases AOM was probably coupled to SR. Islas-Lima et al. (2004) demonstrated for the first time denitrification with CH4 as electron donor in absence of oxygen. Raghoebarsing et al. (2006) demonstrated AOM coupled to nitrite and nitrate reduction by freshwater sediment from Twente kanaal (the Netherlands), this AOM process is mediated by bacteria via a completely other pathway than AOM coupled to SR (Ettwig et al. 2008; Thauer and Shima 2008). From AOM coupled to nitrate or nitrite reduction more energy can be conserved than from AOM coupled SR. The same would be true for AOM coupled to iron (III) or manganese (IV) reduction. Thus far there is no direct evidence for AOM coupled to iron (III) or manganese (IV) reduction; however, Beal et al. (2009) did demonstrate an iron and manganese dependency of methane oxidation in marine sediments.

1.7 Relevance of the anaerobic oxidation of methane for global warming

Estimates of the current human-activity-related CH4 emissions range from 340 to 420 Tg CH4 year−1, while the total natural terrestrial sources are estimated to be between 160 and 270 Tg CH4 year−1 (Khalil and Shearer 2000; Lelieveld et al. 1998; Houweling et al. 1999). The annually CH4 production in anoxic marine sediments is probably more than 85 Tg (Hinrichs and Boetius 2002). CH4 is after CO2 the most important greenhouse gas, responsible for 20% of the infrared radiation trapping in the atmosphere (Mackenzie 1998). The lifetime of CH4 in the atmosphere is shorter than that of CO2, but the strong global warming effect is due to the fact that a relative high fraction of the CH4 occurs in the troposphere. Atmospheric CH4 is mainly oxidized in the troposphere, by the reaction with a hydroxyl radical (OH·), this accounts for a removal of 445–530 Tg CH4 per year. Just 40 Tg CH4 year−1 is transported to the stratosphere. In aerated soils, about 30 Tg CH4 is annually oxidized by aerobic methanotrophs (Khalil and Shearer 2000; Lelieveld et al. 1998; Houweling et al. 1999). Initial AOM was estimated to be responsible for 75 Tg CH4 removal per year (Reeburgh 1996). Later estimates suggested that 300 Tg CH4 was annually removed by AOM (Hinrichs and Boetius 2002), which would make AOM the second most important process for removal of the greenhouse gas CH4.

2 Sulfate reduction in biotechnology

2.1 Environmental problems related with the sulfur cycle

Sulfur compounds are cycled between the earth’s soils, oceans, atmosphere and living matter in the so-called “natural sulfur cycle”. However, due to human activities the emissions of sulfur compounds to surface waters and the atmosphere have increased largely. The earth’s crust contains large amounts of immobilized sulfides. During mining and processing of ores and fossil fuels, sulfide minerals are oxidized and have been emitted to the surface waters, soils and the atmosphere. This has caused major environmental problems like the acidification of surface waters, the mobilization of toxic metals, the increasing salinity of freshwaters and the production of toxic sulfide in anaerobic soils (Morin et al. 2006).

Here three important sources of anthropogenic sulfur emissions are distinguished. The first are waste streams of the mining and metallurgical industry. During the mining of metal ores, minerals like pyrite are biologically oxidized (Johnson 2000), resulting in the production of sulfuric acid and the mobilization of metals. Many metals are toxic for humans and have a devastating effect on ecosystems. This mining wastewater is called acid mine drainage. During the processing of these minerals at metallurgical plants, waste streams with sulfuric acid, sulfur dioxide and residual metals are also produced. The second source of sulfurous emissions is the combustion of fossil fuels. Fossil fuels (like coal, oil and gas) contain S-compounds. Their combustion results in the emission of sulfur dioxide, a major compound in the acid rain formation. Therefore, sulfur dioxide has to be removed from the off-gas (flue gas desulfurization) or sulfur compounds have to be removed from fuels prior to combustion, both processes result in the generation of a waste stream containing the sulfur compounds. A third source are wastewaters contaminated with oxidized sulfur compounds (sulfate, sulfite and thiosulfate) that are produced in industries that use sulfuric acid or sulfate-rich feedstock, e.g. tannery, pulp and paper, textiles, fermentation and the sea food processing industry (Lens et al. 1998). Annually 136 Tg sulfuric acid is used in the industry (Kirk-Othmer 2000).

2.2 Removal and recovery of metals and oxidized sulfur compounds

SR in anaerobic bioreactors treating organic wastes has long been regarded as an unwanted side process due to the loss of electron donor and inhibition of the methanogenic process by sulfide (Colleran et al. 1995; Oude Elferink et al. 1994). Currently, biological SR is an established biotechnological process for the treatment of inorganic waste streams containing sulfur compounds and/or metals (Weijma et al. 2002; Lens et al. 2002). Oxidized sulfur compounds can be converted to elemental sulfur by applying subsequently SR and partial sulfide oxidation (Janssen et al. 1999; van den Bosch 2008). The insoluble sulfur can be recovered by means of a settler and is a safe, storable and reusable product. The hydrophilic nature of biologically produced sulfur makes it an ideal soil fertilizer, in addition, sulfur can be used to produce sulfuric acid (van den Bosch 2008). Most cationic metals, e.g. Zn2+, Cd2+, Cu2+ and Ni2+, can be removed from the solution by precipitation with biologically produced sulfide, the formed insoluble metal sulfides can be separated from the water phase in a settler and reused in the metallurgical industry (Huisman et al. 2006; Veeken et al. 2003). These biological treatment techniques allow the recovery of sulfur and metals; they can be used for the treatment of acid mine drainage, groundwater leachate, industrial wastewaters and industrial waste gases (containing SO2 or H2S). In addition, SR can be applied in situ, in order to immobilize metals as metal sulfides in soils and sediments.

Biological SR forms a relative new alternative to remove sulfate from liquid streams for the widely applied chemical precipitation, in which sodium sulfate or gypsum is produced. Gypsum can be reused as construction material. However, the sulfate containing waste streams from the mining and metallurgical industry are polluted with metals, the produced gypsum will therefore be polluted as well and needs to be stored as chemical waste. For chemical precipitation, large amounts of chemicals are needed, per kg sulfate about 0.8 kg slaked lime is needed. During slaked lime production from limestone CO2 is released, additional to the CO2 produced related to the energy consumption of the process (the process requires a temperature of 900°C). Because of a lower CO2 emission and the production of a reusable product, biological treatment of wastewaters containing sulfate and metals is more sustainable than treatment by chemical precipitation.

2.3 Electron donors for sulfate reduction

The costs of the electron donor forms a major part of the running cost of a SR process and therefore limit the application of biological SR as it cannot always economically compete with chemical precipitation. Cheap electron donors like organic waste streams are not easily degradable and often contain some inert material, which would need to be removed by pre or post treatment. In addition, undesired byproducts can be formed and the quantity and quality of these waste streams is not constant. Easily degradable bulk chemicals are therefore a better option. Such electron donors include hydrogen, synthesis gas, methanol, ethanol, acetate, lactate, propionate, butyrate, sugar, and molasses (Liamleam and Annachhatre 2007), many of which have been extensively investigated as electron donor for SR in bioreactors (Table 2). According to van Houten (1996) hydrogen is the best electron donor at large scale (>5–10 kmol SO4 2− h−1), while ethanol is an interesting electron donor at smaller and middle scale.

2.3.1 Hydrogen

Two advantages of gaseous electron donors are that the wastewater is not diluted and that the electron donor can not wash-out with the effluent. A disadvantage of gaseous electron donors is that they are voluminous and therefore need to be compressed during transportation. High rate SR with H2 as electron donor and carbon dioxide (CO2) as carbon source has been demonstrated at both mesophilic and thermophilic conditions (Table 2). A maximum SR rate of 30 g SO4 2− L−1 day−1 was reached. Van Houten (2006) showed that in a H2 and CO2 fed gas-lift bioreactor, SRB do not take CO2 as sole carbon source, instead they depend on the acetate produced by homoacetogens. Hydrogenotrophic methanogens compete with SRB for the available H2, using CO2 as terminal electron acceptor. In a well-mixed stable-performing bioreactor, the consortium of hetrotrophic SRB and homoacetogens outcompetes methanogens, because of a higher affinity for H2. At elevated H2 concentrations (e.g. during startup, in poorly mixed systems or after a disturbance) methanogens are able to grow, resulting in a loss of electron donor due to methanogenesis (van Houten et al. 2006).

Hydrogen is commonly produced by steam reforming from natural gas or by gasification of oil or coal (Armor 1999; Bartish and Drissel 1978). Steam reforming takes place at high temperatures (750–800°C) and pressures (0.3–2.5 MPa) in the presence of a nickel-based catalyst, the efficiency ranges from 60 to 80%. The gas produced by steam reforming or gasification (synthesis gas) contains, besides hydrogen, between 6 and 60% carbon monoxide (CO; Bartish and Drissel 1978). CO can be removed via the so called water–gas-shift reaction, in which CO and water react over a chemical catalyst at 360°C to form carbon dioxide and hydrogen. To limit methanogenic and homoacetogenic activity the carbon dioxide can subsequently be removed from the gas (e.g. using an alkaline scrubber). More sustainable ways to produce hydrogen are emerging, e.g. gasification of organic waste or biomass (van der Drift et al. 2001), electrolysis using “green” electricity, hydrogenogenic phototrophic microorganisms (Hoekema et al. 2002), dark fermentation (Nath and Das 2004) and biocatalyzed electrolyses in a fuel cell (Rozendal et al. 2006).

2.3.2 Synthesis gas

The chemical water–gas-shift reaction has two disadvantages. Firstly, the chemical catalysts become polluted by hydrogen sulfide which is also present in synthesis gas and secondly, the chemical process requires a high temperature and pressure. Alternatively the untreated synthesis gas, including the CO, could be fed to the SR bioreactor. Van Houten (1995b) found that the SR rate dropped from 12 to 14 g SO4 2− L−1 day−1 to 6–8 g SO4 2− L−1 day−1 when adding 5% CO to the H2/CO2 feed gas. Increasing the percentage CO to 20% did not further deteriorate the SR rate. However, Sipma et al. (2004) showed that some SRB were able to tolerate up to 100% CO. At thermophilic conditions, the responsible microorganisms could convert CO and H2O to H2 and CO2 and simultaneously use the H2 for SR. Although CO is inhibitory for methanogenesis, methanogens could only be eliminated at a short hydraulic retention time (3 h) in a synthesis gas fed gas-lift bioreactor (Sipma et al. 2007).

2.3.3 Methane

Another alternative would be the use of natural gas or biogas directly as electron donor for biological SR. This would have four advantages. Firstly, the steam reforming and the carbon monoxide removal are avoided. These processes contribute to the additional costs of hydrogen over CH4. The costs for the electron donor would be reduced by factor 4 if natural gas instead of hydrogen or ethanol was used as electron donor (Table 3). Secondly, the chemical catalysts used for steam reforming and the water–gas shift are easily polluted by hydrogen sulfide, present in the natural gas or biogas. Sulfide forms no problem when the CH4 containing gas would be fed directly to the bioreactor. Thirdly, energy needed for the transfer of the gas to the liquid can be saved. Four times less gas needs to be transferred from the gas to the liquid phase, as one CH4 can donate eight electrons, and one hydrogen only two. In addition, the solubility of CH4 (1.44 mM in distillated water at 0.101 MPa CH4 and 20°C) is higher than of hydrogen (0.817 mM at 0.101 MPa hydrogen and 20°C). The volumetric conversion rates in bioreactors fed with a gaseous substrate are, in general, limited by the transfer of the gas to the liquid phase.

A third advantage is that substrate losses due to unwanted methanogenesis and acetogenesis (from hydrogen and CO2) can be avoided, only microorganisms involved in AOM coupled to SR are able to grow in a CH4-fed sulfate-reducing bioreactor.

2.4 Reactor type

The gas-lift bioreactor (GLB) is the most common bioreactor type for SR with gaseous electron donors. In this system the transfer of gas to the liquid is optimized. A GLB is usually equipped with a three-phase separator (Esposito et al. 2003; van Houten et al. 1994; Weijma et al. 2002) or an external settler (Sipma et al. 2007) to retain the biomass in the system. GLBs can be operated with (van Houten et al. 1994) or without (Sipma et al. 2007) carrier material like pumice and basalt. Metal-sulfides produced in gas-lift bioreactors can also act as carrier material for the microorganisms.

Membrane bioreactors (MBRs) are relatively new in the field of SR. The advantage is that almost complete biomass retention can be obtained, which is especially useful when slow-growing microorganisms are used. MBRs have been applied in research on SR under high saline conditions (Vallero et al. 2005) and SR at low pH (Bijmans et al. 2008).

2.5 The wastewater treatment process at Nyrstar

At the Nyrstar zinc refinery in Budel (the Netherlands), SR is applied to separate and recover sulfuric acid and zinc from waste streams that also contain other dissolved compounds, e.g. Mg2+ and Cl−. The waste streams are treated in a single-stage hydrogen-fed 500 m3 GLB. In the GLB, SR and zinc-sulfide precipitation take place (Boonstra et al. 1999; Weijma et al. 2002). The sulfate concentration is reduced from 5–15 to 0.05 g L−1, while the zinc concentration is reduced to less than 0.3 mg L−1, recovering about 8.5 tons of zinc-sulfide per day (Boonstra et al. 1999; Weijma et al. 2002). The recovered zinc-sulfide can be directly reused in the zinc smelter. At the Nyrstar zinc refinery, hydrogen produced by steam CH4 reforming is used as electron donor for biological SR. The relative small steam reformer needs 1.88 mol CH4 to reduce 1 mol sulfate.

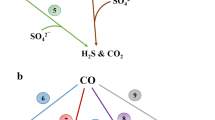

Table 4 compares the current SR process at Nyrstar (Fig. 4a) with the theoretical process if CH4 would be used as electron donor for biological SR (Fig. 4b). From the stoichiometry of AOM coupled to SR, a consumption of one mol CH4 per mol sulfate can be expected. Because less CH4 is needed and less energy is needed for gas recirculation, the carbon dioxide emission of the process in which CH4 is used directly is expected to be half of the current CO2 emission.

3 Microbial aspects of sulfate reduction with methane as electron donor

3.1 Anaerobic methanotrophs

In contrast to aerobic CH4 oxidation, the biochemistry of AOM coupled to SR is not completely understood. AOM is mediated by uncultured Archaea, called anaerobic methanotrophs (ANME). Specific archaeal lipids (biomarkers), from in situ samples, are highly depleted in 13C (Elvert et al. 1999, 2001; Hinrichs et al. 1999, 2000; Thiel et al. 1999, 2001; Pancost et al. 2000). This is evidence that the isotopically light CH4 (biologically produced CH4 is depleted in 13C) was the preferred carbon source for these microorganisms rather than other “heavier” carbon sources. Phylogenetic analysis of AOM sediments identified three novel groups of archaea, called ANME-1, ANME-2 and ANME-3. ANME-1 and ANME-2 are most abundant and geographically widespread. ANME are phylogenetically distantly related to cultivated methanogenic members from the orders Methanosarcinales and Methanomicrobiales (Hinrichs et al. 1999; Orphan et al. 2002; Knittel et al. 2005; Niemann et al. 2006). Orphan et al. (2001a, 2002) combined isotopic and phylogenetic analysis and showed that cells belonging to ANME-1 and ANME-2 assimilated carbon from CH4 during AOM.

3.2 Reversed methanogenesis

AOM is a form of reversed methanogenesis: AOM is like methanogenesis inhibited by bromoethanesulfonate (BES; Nauhaus et al. 2005), ANME-1 cells were found to contain most of the genes typically associated with CH4 production (Hallam et al. 2003, 2004) and an analogue of the methyl-coenzyme M reductase was found to make up 7% of the extracted soluble proteins from an AOM mediating microbial mat from the Black Sea (Krüger et al. 2003). The ∆G°′ of the reduction of methyl-coenzyme M to produce CH4 is −30 (±10) kJ mol−1, the back reaction becomes exogenic when the product to substrate concentration ratio is ~105, such a ratio is physiologically not unrealistic (Thauer and Shima 2008). In addition, pure cultures of methanogenic archaea and methanogenic mixed cultures also oxidize CH4 to CO2 in the absence of oxygen, but in low amounts and during net methanogenesis (Zehnder and Brock 1979; Harder 1997; Moran et al. 2004; Moran et al. 2007; Meulepas et al. 2010). SRB did not show any CH4 oxidation during SR (Harder 1997).

Thus far, there is no direct evidence that ANME are capable of methanogenesis. However, AOM and CH4 production occur simultaneously in microbial mats from the Black Sea (Seifert et al. 2006), in sediments from Cape Lookout Bight (North Carolina; Hoehler et al. 1994) and in sediments from the Golf of Mexico (Orcutt et al. 2005). CH4 production by Hydrate Ridge sediment on hydrogen, formate, acetate and methanol, in absence of CH4, was an order of a magnitude lower than the AOM rate though (Nauhaus et al. 2002), and microbial mats from the Black Sea did not show any CH4 production in presence of hydrogen and absence of sulfate (Treude et al. 2007). In addition, growth of ANME on solely methanogenic substrates has not been reported.

3.3 SRB associated with AOM

Some archaea (belonging to the Euryarchaeota or Crenarchaeota) are capable of SR (Muyzer and Stams 2008). However, in the archaea belonging to the ANME groups, no gene analogues for enzymes involved in SR were found (Thauer and Shima 2008). In addition, methyl-coenzyme M reductase was shown to be inhibited by sulfite, an intercellular intermediate of SR (Mahlert et al. 2002). Therefore, it is unlikely that AOM and SR take place in the same cell (Shima and Thauer 2005). At AOM sites, ANME co-occur with SRB belonging taxonomically to the delta group of proteobacteria and associated with the Desulfosarcina/Desulfococcus cluster (Boetius et al. 2000; Orphan et al. 2001b; Michaelis et al. 2002; Elvert et al. 2003; Knittel et al. 2003). During incubations of AOM sediment with 13C-labeled CH4, 13C was incorporated both in archaeal lipids associated with ANME and bacterial lipids associated with SRB. This incorporation in bacterial lipids might proceed via a carbon compound produced from CH4 by ANME rather than by the direct uptake of CH4 by SRB (Blumenberg et al. 2005). It has frequently been suggested that an archaeon produces an electron carrier compound from CH4 that is utilized by a sulfate-reducing partner (Fig. 5; Zehnder and Brock 1980; Alperin and Reeburgh 1985; Hoehler et al. 1994 and DeLong 2000). In sediment from Hydrate Ridge, Eel River Basin and the Golf of Mexico, ANME-2 and SRB live in consortia with a diameter of up to circa 20 μm (Boetius et al. 2000; Hinrichs et al. 2000; Knittel et al. 2005). Moreover, both microorganisms were growing in consortia with CH4 and sulfate as sole substrates (Nauhaus et al. 2007), confirming the involvement of the SRB in AOM coupled to SR.

These ANME/SRB aggregates are not dominant in all AOM sites though. In Black sea microbial mats, SRB mainly occur in microcolonies surrounded by bulk ANME-1 cells clusters (Michaelis et al. 2002; Knittel et al. 2005). The distances between ANME and SRB in those microbial mats are larger than in the consortia from Hydrate Ridge. In samples from Eel River Basin ANME-1 archaeal group frequently existed in monospecific aggregates or as single filaments, apparently without a bacterial partner (Orphan et al. 2002). In Eckernförde Bay sediment and in an Eckernförde Bay enrichment, clusters of ANME-2 cells were found without sulfate-reducing partners (Treude et al. 2005a; Jagersma et al. 2009).

3.4 Possible syntrophic routes

Given the evidence for reversed methanogenesis, hydrogen (reactions 3 and 4) and acetate (reactions 5 and 6) were initially proposed to act as interspecies electron carrier (IEC; Hoehler et al. 1994; DeLong 2000). The standard Gibbs free energy change at pH 7 (∆G°′) of the production of these IECs from CH4 is positive, however, when the IEC concentration is kept low enough by the sulfate-reducing partner, the ∆G will be negative.

There are some thermodynamic concerns about this theory. At in situ conditions there is only −22 kJ mol−1 available for AOM coupled to SR (Harder 1997). This energy would need to be shared between the syntrophic partners. Methanogenic archaea have been shown to require a free energy change of at least −10 kJ mol−1 and SRB of at least −19 kJ mol−1 to support their metabolism in situ (Hoehler et al. 2001; Dale et al. 2006). The in situ free energy change is therefore probably not sufficiently large to fuel the energy metabolism of two microorganisms (Schink 1997; Thauer and Shima 2008). Moreover, for diffusive transport between the syntrophic partners a concentration gradient is needed. Therefore, the IEC concentration near the SRB will be lower than the concentration near the ANME and the actual available energy for the microorganisms will be even lower. The bigger the distance between the syntrophic partners the greater the loss (Sørensen et al. 2001). Thermodynamic calculations excluded hydrogen, acetate and methanol as IEC, because the maximum diffusion distances of those compounds at in situ concentrations and rates were smaller than the thickness of two prokaryotic cell walls (Sørensen et al. 2001). Also activity assays provided evidence against potential IECs. SR activity of Hydrate Ridge sediment with hydrogen, formate or acetate was lower than SR activity on CH4, indicating that SRB involved in AOM, were not adapted to these substrates (Nauhaus et al. 2002, 2005). Moreover, Meulepas (2009) excluded hydrogen, formate, acetate methanol and carbon monoxide as IEC’s in AOM by an ANME-2 enrichment. It therefore remains unclear if and how reducing equivalents are transferred from the ANME to a sulfate-reducing partner.

4 Biotechnological aspects of sulfate reduction with methane as electron donor

SR coupled to AOM has thus far mostly been studied to get a better understanding of carbon and sulfur cycling in nature. However, recent physiological in vitro and bioreactor studies provided insights in the potential of sulfate reduction with methane as electron donor for applications, and the operational window of such process.

4.1 Effect of temperature, pH and salinity

The SR rates of Hydrate Ridge sediment, Black Sea microbial mats, Eckernförde Bay sediment and Eckernförde Bay enrichment were highest between 5 and 16°C (Nauhaus et al. 2005), 16 and 24°C (Nauhaus et al. 2005), 20 and 28°C (Treude et al. 2005a), and 15 and 25°C (Meulepas et al. 2009b), respectively. For biotechnological applications, the low temperature optima form a limitation, as many industrial wastewaters are warmer than 20°C. However, in many countries legislation requires treated wastewater to be cooled before discharge. Moreover, if the wastewater is cooled in a heat exchanger the energy loss can be minimized.

Many sulfate and metal containing wastewaters are acid (Weijma et al. 2002; Kaksonen and Puhakka 2007). AOM coupled to SR has thus far not been demonstrated at acid conditions; the CH4 oxidation and sulfate reduction rates of an Eckernförde Bay enrichment were the highest at a pH of 7.5 and a salinity of 30‰ (Meulepas et al. 2009b), which are common optima for marine microorganisms. However, below a pH of 6.5, H2S and CO2 will be the main products of sulfate reduction, instead of HS− and HCO3 −. This will result in the generation of alkalinity. Therefore, a sulfate-reducing bioreactor fed with acidic wastewater, can often be maintained at a neutral pH. The high salinity requirement makes that wastewaters low in salts (other than sulfate) cannot be treated with the AOM biomass from marine sediments. However, for applications in which the liquid is recirculated (e.g. flue gas desulfurization; Lens et al. 2003), a high salinity optimum is even an advantage, since salts accumulate in such treatment systems. Figure 6a shows a flue gas desulfurization process in which methane is used as electron donor.

Schematic representation of a biological zinc removal process, in which sulfate reduction and metal precipitation are separated in order to prevent a loss in methanotrophic sulfate-reduction biomass (a). Schematic representation of biological flue gas desulfurization with methane as electron donor (b)

4.2 Effect of substrate and product concentrations

There is a positive relation between the conversion rate and the CH4 partial pressure in CH4-oxidizing sulfate-reducing sediments (Krüger et al. 2005; Nauhaus et al. 2005) and enrichments (Meulepas et al. 2009b), even up to a pressure of 45 MPa (Kallmeyer and Boetius 2004). This implies that at ambient pressure sulfate reduction with methane as electron donor is always limited by the CH4 partial pressure. This could be overcome by applying elevated CH4 partial pressures. However, the energy required to pressurize CH4 and the additional safety hazards make the use of high-pressure bioreactor at full-scale less appealing. For ambient-pressure applications, it would be advisable to optimize the availability of CH4 for the microorganisms by applying thorough mixing, CH4 gas sparging and gas recirculation.

The ability of a CH4-oxidizing sulfate-reducing Eckernförde Bay enrichment to remove sulfate almost completely (down to 0.05 mM; Meulepas et al. 2009b), makes it possible to use this process for sulfate removal.

Sulfide is toxic for all sulfate-reducing bacteria and methanogenic archaea. The toxicity of sulfide of often associated with its undissociated form (H2S) due to the facilitated passage of neutral molecules across cell membranes and to its reactivity with cellular compounds (O’Flaherty et al. 1998). However, the sulfide tolerance of different OAM communities seem to vary; sulfide accumulated to maximum 2.4 mM (Meulepas et al. 2009b), 10 mM (Joye et al. 2004), 14 mM (Nauhaus et al. 2005) and 15 mM (Valentine 2002) in CH4-oxidizing sulfate-reducing sediments.

4.3 Alternative electron acceptors

Sediments or enrichments mediating sulfate reduction with methane as electron donor, were not able to utilize nitrate (Meulepas et al. 2009b), fumarate, iron(III) or Mn(IV; Nauhaus et al. 2005) as alternative electron acceptor for methane oxidation, but were able to use thiosulfate and sulfite (Meulepas et al. 2009b). These alternative electron acceptors have application possibilities as well. Thiosulfate containing wastewater is produced at pulp bleaching and by the photographs fixing process (Lens et al. 1998), and sulfite is the main compound in the liquid from flue gas scrubbing.

4.4 Growth in bioreactors

Estimates of the doubling time of the microorganisms mediating AOM coupled to SR vary from 1 to 7 months (Girguis et al. 2005; Nauhaus et al. 2007; Krüger et al. 2008; Meulepas et al. 2009a). Because of this low growth rate, biomass retention is crucial for applications of the process. Meulepas et al. (2009a) showed that CH4-oxidizing sulfate-reducing biomass could be grown in an ambient-pressure MBR. A MBR allows complete cell retention, but requires energy input to overcome the trans-membrane pressure and to prevent clogging. Thus far, it is unknown whether sufficient CH4-oxidizing sulfate-reducing biomass can be retained in a bioreactor by settling alone, like in gas-lift bioreactors or UASB systems. Although the turbulent conditions encountered in a MBR did not seem to be a problem for CH4-oxidizing sulfate-reducing mixed-cultures (Meulepas et al. 2009a), the formation of CH4-oxidizing sulfate-reducing biofilms under turbulent reactor conditions has not yet been described. Naturally AOM mediating biofilms do occur though, in the form of microbial mats in the Black Sea (Michaelis et al. 2002).

From the growth rate (μ) and the specific conversion rate (V), the growth yield (Y) can be calculated according to the formula Y = μV−1. Nauhaus et al. (2007) calculated a molar yield of 0.6 g cell dry weight (mol CH4 oxidized)−1. This was based on the sulfate reduction rate per gram ANME/SRB consortia. The low growth yield makes it difficult to combine AOM coupled to SR and metal precipitation in one system, since the metal sulfides need to be harvested without a loss of biomass. However, sulfate reduction with CH4 as electron donor can be used to remove and recover metals from wastewater if SR and metal precipitation are separated, like illustrated in Fig. 6b.

5 Recommendations for further research

The low growth rate of the microorganisms mediating AOM coupled to SR forms a major bottleneck for biotechnological applications. The thus far highest AOM and SR rate obtained in a bioreactor is 1.0 mmol g −1VSS day−1 (Meulepas et al. 2009a). The full-scale sulfate-reducing bioreactor at Nyrstar (Budel, the Netherlands) is capable of reducing 87.5 kmol (8.4 ton) sulfate per day (Weijma et al. 2002). At a doubling time of 3.8 months (Meulepas et al. 2009a), it would take 8.6 years to grow enough CH4-oxidizing sulfate-reducing biomass from the 1L enrichment obtained by Meulepas et al. (2009a), to be able to replace the current process at Nyrstar, in which hydrogen is supplied as electron donor for biological sulfate reduction. Once enough CH4-oxidizing sulfate-reducing biomass is produced, an operational failure, resulting in biomass wash-out or decay, could set the operation a few years back.

Alternatively, large amounts of AOM biomass could be sampled from the seafloor and used as inoculum for full-scale bioreactors. The highest AOM rate of a natural AOM enrichment is 8–21 μmol g −1dw day−1 (Black Sea microbial mats; Treude et al. 2007). At least 4,100 ton dry weight sediment would be needed to replace the current sulfate reduction process; this is from a technological, economical and ecological point of view undesirable. Thus, for biotechnological applications it is essential that CH4-oxidizing sulfate-reducing biomass can be grown much faster. Three approaches to obtain faster growth rates are discussed below.

5.1 Other inocula

One straight forward approach is to inoculate bioreactors with more promising AOM inocula than the inocula that have been used so far, e.g. Black Sea microbial mats or sediments from thermophilic CH4 seeps. Black Sea microbial mats form the most active natural AOM inocula, the dissolved methane concentrations below the microbial mats can reach up to 85 mM (Wallmann et al. 2006). Possibly, the relative high conversion rates and dissolved methane concentrations are related to faster maximum growth rates.

Kallmeyer and Boetius (2004) reported that the AOM rate in Hydrothermal Sediment was maximal between 35 and 90°C. Possibly thermophilic anaerobic methanotrophs can also grow faster than ANME from cold-seeps. It would be worth to investigate the growth of the microorganisms, mediating AOM coupled to SR, sampled at a thermophilic “Lost city” site (Boetius 2005).

5.2 Other incubation techniques

A second approach is to test novel incubation techniques to enrich the microorganisms responsible for SR coupled to AOM, e.g. hollow-fiber bioreactors, continuous high-pressure bioreactors or microbial fuel cells. Hollow fibers are semi-permeable tubes, via which for example CH4 can be supplied to microorganisms growing in a biofilm on the fiber. At the other site of the semi-permeable tube, the sulfate containing liquid phase can be recirculated and refreshed. Diffusion distances in such system are minimal and the shear forces are low compared to gas-lift bioreactors or membrane bioreactors. High shear forces might hamper the formation of CH4-oxidizing sulfate-reducing biofilms.

The methane partial pressure positively affected the AOM rate (Nauhaus et al. 2002; Krüger et al. 2005; Kallmeyer and Boetius 2004; Meulepas et al. 2009a) and the Gibbs free energy change of AOM coupled to SR (Valentine 2002). Therefore, the growth of the AOM mediating microorganisms is expected to be faster at elevated CH4 partial pressures. Although, high pressure bioreactors might not be practical for waste water treatment, they might be ideal to grow sludge as long as a high methane partial pressure can be combined with biomass retention and sulfide removal. Deusner et al. (2009) demonstrated AOM in continuous high pressure bioreactors.

It has been suggested that electrons are transferred from ANME to SRB via extracellular redox shuttles (Widdel and Rabus 2001; Wegener et al. 2008), via membrane bound redox shuttles or so called “nanowires” (Reguera et al. 2005; Stams et al. 2006; Thauer and Shima 2008; Wegener et al. 2008). If this is indeed the case, the methane oxidizers could selectively be grown on a methane-fed anode and the involved sulfate reducers on a sulfate-fed cathode of a microbial fuel cell.

5.3 Growth on alternative substrates

A third approach is to grow anaerobic methanotrophs on alternative substrates. A sulfate-reducing CH4-oxidizing enrichment was able to utilize thiosulfate and sulfite as alternative electron acceptor for sulfate (Meulepas et al. 2009b), and acetate, formate, carbon monoxide and hydrogen as alternative electron donor for CH4 (Meulepas 2009c). Given the larger Gibbs free energy change of these conversions, compared to AOM coupled to SR, higher growth rates can be expected on those substrates. If the same microorganisms are involved in both these alternative conversions and AOM coupled to SR, they could probably be enriched faster on those alternative substrates.

References

Alperin MJ (1989) The carbon cycle in an anoxic marine sediment: concentrations, rates, isotope ratios, and diagenetic models. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Alaska, Fairbanks

Alperin MJ, Reeburgh WS (1985) Inhibition experiments on anaerobic methane oxidation. Appl Environ Microbiol 50(4):940–945

Alperin MJ, Reeburgh WS, Whiticar MJ (1988) Carbon and hydrogen isotope fractionation resulting from anaerobic methane oxidation. Global Biogeochem Cycles 2:279–288

Amaral JA, Knowles R (1995) Growth of methanotrophs in methane and oxygen counter gradients. FEMS Microbiol Lett 126:215–220

Anthony C (1982) The biochemistry of methylotrophs. Academic Press, London

Armor JN (1999) The multiple roles for catalysis in the production of H2. Appl Catal A Gen 176:159–176

Barnes R, Goldberg E (1976) Methane production and consumption in anoxic marine sediments. Geology 4:297–300

Bartish CM, Drissel GM (1978) Carbon monoxide. In: Krirk-Othmer R (ed) Encyclopedia of chemical technology. Wiley, NY, pp 772–793

Beal EJ, House CH, Orphan VJ (2009) Manganese- and iron-dependent marine methane oxidation. Science 325:184–187

Bijmans MFM, Peters TWT, Lens PNL, Buisman CJN (2008) High rate sulfate reduction at pH 6 in a pH-auxostat submerged membrane bioreactor fed with formate. Water Res 42:2439–2448

Blair NE, Aller RC (1995) Anaerobic methane oxidation on the Amazon shelf. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 59:3707–3715

Blumenberg M, Seifert R, Nauhaus K, Pape T, Michaelis W (2005) In vitro study of lipid biosynthesis in an anaerobically methane-oxidizing microbial mat. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:4345–4351

Boetius A (2005) Lost city live. Science 307:1420–1422

Boetius A, Suess E (2004) Hydrate ridge: a natural laboratory for the study of microbial life fueled by methane from near-surface gas hydrates. Chem Geol 205(3–4):291–310

Boetius A, Ravenschlag K, Schubert CJ, Rickert D, Widdel F, Gieseke A, Amann R, Jørgensen BB, Witte U, Pfannkuche O (2000) A marine microbial consortium apparently mediating anaerobic oxidation of methane. Nature 407:623–626

Boonstra J, van Lier R, Janssen G, Dijkman H and Buisman CJN (1999) Biological treatment of acid mine drainage. In: Amils R, Ballester A (eds) Biohydrometallurgy and the environment toward the mining of the 21st century. process metallurgy, vol 9B. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 559–567

Bottrell SH, Newton RJ (2006) Reconstruction of changes in global sulfur cycling from marine sulfate isotopes. Earth Sci Rev 75:59–83

Castro HF, Williams NH, Ogram A (2000) Phylogeny of sulfate-reducing bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 31:1–9

Chang S, Des Marais D, Mac R, Miller SL, Strathearn GE (1983) Prebiotic organic synthesis and origin of life. In: Schopf JW (ed) Earth′s earliest biosphere—its origin and evolution. Proncton University Press, Pronceton, pp 99–139

Colleran E, Finnegan S, Lens P (1995) Anaerobic treatment of sulphate-containing waste streams. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 67:29–46

Costa C, Dijkema C, Friedrich M, García P, Encina-Encina P, Fernández-Polanco P, Stams AJM (2000) Denitrifcation with methane as electron donor in oxygen-limited bioreactors Appl. Microbiol Biotechnol 53:754–762

Crabtree RH (1995) Aspects of methane chemistry. Chem Rev 95:987–1007

Damm E, Budéus G (2003) Fate of vent derived methane in seawater above the Haakon Mosby mud volcano (Norwegian Sea). Mar Chem 82:1–11

Daniels L, Fuchs G, Thauer RK, Zeikus JG (1977) Carbon monoxide oxidation by methanogenic bacteria. J Bacteriol 132:118–126

DeLong EF (2000) Resolving a methane mystery. Nature 407:577–579

Deppenmeier U, Müller V, Gottschalk G (1996) Pathways of energy conservation in methanogenic archaea. Arch Microbiol 165:149–163

Deusner C, Meyer V, Ferdelman TG (2009) High-pressure systems for gas-phase free continuous incubation of enriched marine microbial communities performing anaerobic oxidation of methane. Biotechnol Bioengin. doi:10.1002/bit.22553

Dries J, De Smul A, Goethals L, Grootaerd H, Verstraete W (1998) High rate biological treatment of sulfate-rich wastewater in an acetate-fed EGSB reactor. Biodegradation 9:103–111

du Preez LA, Maree JP (1994) Pilot-scale biological sulphate and nitrate removal utilizing producer gas as energy source. Water Sci Technol 30:275–285

Eller G, Känel L, Krüger M (2005) Co-occurrence of aerobic and anaerobic methane oxidation in the water column of Lake Plußsee. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:8925–8929

Elvert M, Suess E, Whiticar MJ (1999) Anaerobic methane oxidation associated with marine gas hydrates: superlight C-isotopes from saturated and unsaturated C20 and C25 irregular isoprenoids. Naturwissenschaften 86:295–300

Elvert M, Greinert J, Suess E, Whiticar MJ (2001) Carbon isotopes of biomarkers derived from methane-oxidizing microbes at Hydrate Ridge, Cascadia convergent margin. In: Paull CK, Dillon WP (eds) Natural gas hydrates: occurrence, distribution, and dynamics. American Geophysical Union, Washington, pp 115–129

Elvert M, Boetius A, Knittel K, Jørgensen BB (2003) Characterization of specific membrane fatty acids as chemotaxonomic markers for sulphate-reducing bacteria involved in anaerobic oxidation of methane. Geomicrobiol J 20:403–419

Esposito G, Weijma J, Pirozzi F, Lens PNL (2003) Effect of the sludge retention time on H2 utilization in a sulphate reducing gas-lift reactor. Process Biochem 39:491–498

Ettwig KF, Shima S, van de Pas-Schoonen KT, Kahnt J, Medema MH, op den Camp HJM, Jetten MSM, Strous M (2008) Denitrifying bacteria anaerobically oxidize methane in the absence of Archaea. Environ Microbiol 10(11):3164–3173

Frankin RJ (2001) Full-scale experiences with anaerobic treatment of industrial wastewater. Water Sci Technol 44(8):1–6

Girguis PR, Orphan VJ, Hallam SJ, DeLong EF (2003) Growth and methane oxidation rates of anaerobic methanotrophic archaea in a continuous-flow bioreactor. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:5472–5482

Girguis PR, Cozen AE, DeLong EF (2005) Growth and population dynamics of anaerobic methane-oxidizing archaea and sulphate-reducing bacteria in a continuous flow bioreactor. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:3725–3733

Grossman EL, Cifuentes LA, Cozzarelli IM (2002) Anaerobic methane oxidation in a landfill-leachate plume. Environ Sci Technol 36:2436–2442

Hallam SJ, Girguis PR, Preston CM, Richardson PM, DeLong EF (2003) Identification of methyl coenzyme M reductase A (mcrA) genes associated with methaneoxidizing Archaea. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:5483–5491

Hallam SJ, Putnam N, Preston CM, Detter JC, Rokhsar D, Richardson PM, DeLong EF (2004) Reverse methanogenesis: testing the hypothesis with environmental genomics. Science 305:1457–1462

Hanson RS, Hanson TE (1996) Methanotrophic bacteria. Microbiol Rev 60(2):439–471

Harder J (1997) Anaerobic methane oxidation by bacteria employing 14C-methane uncontaminated with 14C-carbon monoxide. Mar Geol 137:13–23

Harper SR, Pohland FG (1986) Recent developments in hydrogen management during anaerobic biological wastewater treatment. Biotechnol Bioeng 28:585–602

Hinrichs K-U, Boetius A (2002) The anaerobic oxidation of methane: new insights in microbial ecology and biogeochemistry. In: Wefer G, Billet D, Hebbeln D, Jørgensen BB, Schlüter M, van Weering T (eds) Ocean margin systems. Springer, Heidelberg, pp 457–477

Hinrichs K-U, Hayes JM, Sylva SP, Brewer PG, DeLong EF (1999) Methane-consuming archaebacteria in marine sediments. Nature 398:802–805

Hinrichs K-U, Summons RE, Orphan V, Sylva SP, Hayes JM (2000) Molecular and isotopic analyses of anaerobic methane-oxidizing communities in marine sediments. Org Geochem 31:1685–1701

Hoehler TM, Alperin MJ, Albert DB, Martens CS (1994) Field and laboratory studies of methane oxidation in an anoxic marine sediment: evidence for a methanogen-sulfate reducer consortium. Global Biogeochem Cycles 8(4):451–463

Hoehler TM, Alperin MJ, Albert DB, Martens CS (2001) Apparent minimum free energy requirements for methanogenic Archaea and sulfate-reducing bacteria in an anoxic marine sediment. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 38:33–41

Hoekema S, Bijmans M, Janssen M, Tramper J, Wijffels RH (2002) A pneumatically agitated flat-panel photobioreactor with gas re-circulation: Anaerobic photoheterotrophic cultivation of a purple non-sulfur bacterium. Int J Hydrogen Energy 27(11):1331–1338

Holmer M, Storkholm P (2001) Sulphate reduction and sulphur cycling in lake sediments: a review. Freshw Biol 46:431–451

Houghton JT, Ding Y, Griggs DJ et al (eds) (2001) Trace gases: current observations, trends and budgets. In: Climate change 2001: the scientific basis: contribution of working group I to the third assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 248–254

Houweling S, Kaminski T, Dentener F, Lelieveld J, Heimann M (1999) Inverse modelling of methane sources and sinks using the adjoint of a global transport model. J Geophys Res 104(26):137–160

Huisman JL, Schouten G, Schultz C (2006) Biologically produced sulphide for purification of process streams, effluent treatment and recovery of metals in the metal and mining industry. Hydrometallurgy 83:106–113

Islas-Lima S, Thalasso F, Gomez-Hernandez J (2004) Evidence of anoxic methane oxidation coupled to denitrification. Water Res 38:13–16

Iversen N, Jørgensen BB (1985) Anaerobic methane oxidation rates at the sulfate-methane transition in marine sediments from Kattegat and Skagerrak (Denmark). Limnol Oceanogr 30(5):944–955

Iversen N, Oremland RS, Klug MJ (1987) Big Soda Lake (Nevada). 3. Pelagic methanogenesis and anaerobic methane oxidation. Limnol Oceanogr 32(4):804–814

Jagersma CG, Meulepas RJW, Heikamp-de Jong I, Gieteling J, Klimiuk A, Schouten S, Sinninghe Damsté JS, Lens PNL, Stams AJM (2009) Microbial diversity and community structure of a highly active anaerobic methane oxidizing sulfate-reducing enrichment. Environ Microbiol 11(12):3223–3232

Janssen AJH, Lettinga G, de Keizer A (1999) Removal of hydrogen sulphide from wastewater and waste gases by biological conversion to elemental sulphur: colloidal and interfacial aspects of biologically produced sulphur particles. Colloids Surf A 151:389–397

Johnson D (2000) Biological removal of sulfurous compounds from inorganic wastewaters. In: Lens PNL, Hulshoff Pol LW (eds) Environmental technologies to treat sulfur pollution: principles and engineering. IWA, London, pp 175–206

Joye SB, Connell TL, Miller LG, Oremland RS, Jellison RS (1999) Oxidation of ammonia and methane in an alkaline, saline lake. Limnol Oceanogr 44:178–188

Joye AB, Boetius A, Orcutt BN, Montoya JP, Schulz HN, Erickson MJ, Lugo SK (2004) The anaerobic oxidation of methane and sulfate reduction in sediments from Gulf of Mexico cold seeps. Chem Geol 205:219–238

Kaksonen AH, Puhakka JA (2007) Sulfate reduction based bioprocesses for the treatment of acid mine drainage and the recovery of metals. Eng Life Sci 7(6):541–564

Kaksonen AH, Franzmann PD, Puhakka JA (2004) Effect of hydraulic retention time and sulfide toxicity on ethanol and acetate oxidation in sulfate-reducing metal-precipitating fluidized-bed reactor. Biotechnol Bioeng 86:332–343

Kallmeyer J, Boetius A (2004) Effects of temperature and pressure on sulfate reduction and anaerobic oxidation of methane in hydrothermal sediments of guaymas basin. Appl Environ Microbiol 70(20):1231–1233

Khalil M, Shearer MJ (2000) Sources of methane: an overview. In: Khalil M (ed) Atmospheric methane: its role in the global environment. Springer, New York, pp 98–111

Kirk-Othmer (2000) Encyclopidia of chemical technology. Wiley, New York

Knittel K, Boetius A, Lemke A, Eilers H, Lochte K, Pfannkuche O, Linke P (2003) Activity, distribution, and diversity of sulfate reducers and other bacteria above gas hydrate (Cascadia Margin, OR). Geomicrobiol J 20:269–294

Knittel K, Lösekann T, Boetius A, Kort R, Amann R (2005) Diversity and distribution of methanotrophic archaea at cold seeps. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:467–479

Krüger M, Meyerdierks A, Glöckner FO, Amann R, Widdel F, Kube Reinhardt R, Kahnt J, Böcher R, Thauer RK, Shima S (2003) A conspicuous nickel protein in microbial mats that oxidize methane anaerobically. Nature 426:878–881

Krüger M, Treude T, Wolters H, Nauhaus K, Boetius A (2005) Microbial methane turnover in different marine habitats. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 227:6–17

Krüger M, Wolters H, Gehre M, Joye SB, Richnow H-H (2008) Tracing the slow growth of anaerobic methane-oxidizing communities by 15N-labelling techniques. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 63:401–411

Kvenvolden KA (1995) A review of the geochemistry of methane in natural gas hydrate. Org Geochem 23:997–1008

Lee SG, Goo JH, Kim HG, Oh J-I, Kim JM, Kim SW (2004) Optimiation of methanol biosynthesis from methane using Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b. Biotechnol Lett 26:947–950

Lelieveld J, Crutzen PJ, Dentener FJ (1998) Changing concentration, lifetime and climate forcing of atmospheric methane. Tellus B 50(2):128–150

Lens PNL, Visser A, Janssen AJH, Hulshoff Pol LW, Lettinga G (1998) Biotechnological treatment of sulfate-rich wastewaters. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol 28(1):41–88

Lens P, Vallero M, Esposito G, Zandvoort M (2002) Perspectives of sulfate reducing bioreactors in environmental biotechnology. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol 1:311–325

Lens PNL, Gastesi R, Lettinga G (2003) Use of sulfate reducing cell suspension bioreactors for the treatment of SO2 rich flue gases. Biodegradation 14:229–240

Lettinga G, van Haandel AC (1993) Anaerobic treatment for energy production and environmental protection. In: Johansson TB et al (eds) Renewable energy. Island Press, Washington, DC, pp 817–839

Liamleam W, Annachhatre AP (2007) Electron donors for biological sulfate reduction. Biotechnol Adv 25:452–463

Mackenzie FT (1998) Our changing planet: an introduction to earth system science and global environmental change. Prentice Hall, New Jersey 486 p

Mahlert F, Bauer C, Jaun B, Thauer RK, Duin EC (2002) The nickel enzyme methyl-coenzyme M reductase from methanogenic archaea: in vitro induction of the nickel-based MCR-ox EPR signals from MCR-red2. J Biol Inorg Chem 7:500–513

Martens CS, Berner RA (1974) Methane production in the interstitial waters of sulfate-depleted marine sediments. Science 185:1167–1169

Martens CS, Berner RA (1977) Interstitial water chemistry of anoxic Long Island Sound sediments. I. Dissolved gases. Limnol Oceanogr 22:10–25

Martens CS, Albert DB, Alperin MJ (1999) Stable isotope tracing of anaerobic methane oxidation in the gassy sediments of Eckernforde Bay, German Baltic Sea. Am J Sci 299:589–610

Meulepas RJW (2009) Biotechnological aspects of anaerobic oxidation of methane coupled to sulfate reduction. PhD thesis, Wageningen university, Wageningen, The Netherlands

Meulepas RJW, Jagersma CG, Gieteling J, Buisman CJN, Stams AJM, Lens PNL (2009a) Enrichment of anaerobic methanotrophs in a sulfate-reducing membrane bioreactor. Biotechnol Bioeng 104(3):458–470

Meulepas RJW, Jagersma CG, Khadem AF, Buisman CJN, Stams AJM, Lens PNL (2009b) Effect of environmental conditions on sulfate reduction with methane as electron donor by an Eckernförde bay enrichment. Environ Sci Technol 43(17):6553–6559

Meulepas RJW, Jagersma CG, Zhang Y, Petrillo M, Cai H, Buisman CJN, Stams AJM, Lens PNL (2010) Trace methane oxidation and the methane-dependency of sulfate reduction in anaerobic granular sludge. FEMS Microbiol Ecol (in press)

Michaelis W, Seifert R, Nauhaus K, Treude T, Thiel V, Blumenberg M, Knittel K, Gieseke A, Peterknecht K, Pape T, Boetius A, Amann R, Jørgensen BB, Widdel F, Peckmann J, Pimenov NV, Gulin MB (2002) Microbial reefs in the black sea fueled by anaerobic oxidation of methane. Science 297:1014–1015

Moran JJ, House CH, Freeman KH, Ferry JG (2004) Trace methane oxidation studied in several Euryarchaeota under diverse conditions. Archaea 1:303–309

Moran JJ, House CH, Thomas B, Freeman KH (2007) Products of trace methane oxidation during nonmethyltrophic growth by Methanosarcina. J Geophys Res 112:1–7

Morin D, Lips A, Pinches A, Huisman J, Frias C, Norberg A, Forssberg E (2006) BioMinE—integrated project for the development of biotechnology for metal-bearing materials in Europe. Europe Hydrometallurgy 83:69–76

Mueller-Langer F, Tzimas E, Kaltschmitt M, Peteves S (2007) Techno-economic assessment of hydrogen production processes for the hydrogen economy for the short and medium term. Int J Hydrogen Energy 32:3797–3810

Muyzer G, Stams AJM (2008) The ecology and biotechnology of sulphate-reducing bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 6:441–454

Nath K, Das D (2004) Improvement of fermentative hydrogen production: various approaches. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 65:520–529

Nauhaus K, Boetius A, Krüger M, Widdel F (2002) In vitro demonstration of anaerobic oxidation of methane coupled to sulphate reduction in sediment from a marine gas hydrate area. Environ Microbiol 4(5):296–300

Nauhaus K, Treude T, Boetius A, Krüger M (2005) Environmental regulation of the anaerobic oxidation of methane: a comparison of ANME-I and ANME-II communities. Environ Microbiol 7(1):98–106

Nauhaus K, Albrech M, Elvert M, Boetius A, Widdel F (2007) In vitro cell growth of marine archaeal-bacterial consortia during anaerobic oxidation of methane with sulfate. Environ Microbiol 9(1):187–196

Niemann H, Duarte J, Hensen C, Omoregie E, Magalhães VH, Elvert M, Pinheiro LM, Kopf A, Boetius A (2006) Microbial methane turnover at mud volcanoes of the Gulf of Cadiz. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 70:5336–5355

Niewöhner C, Hensen C, Kasten S, Zabel M, Schulz HD (1998) Deep sulfate reduction completely mediated by anaerobic methane oxidation in sediments of the upwelling area off Namibia. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 62:455–464

O’Brien JM, Wolkin RH, Moench TT, Morgan JB, Zeikus JG (1984) Association of hydrogen metabolism with unitrophic or mixotrophic growth of Methanosarcina barkeri on carbon monoxide. J Bacteriol 158:373–375

O’Flaherty V, Mahony T, O’Kennedy R, Colleran E (1998) Effect of pH on growth kinetics and sulphide toxicity thresholds of a range of methanogenic, syntrophic and sulphate-reducing bacteria. Process Biochem 33(5):555–569

Orcutt B, Boetius A, Elvert M, Samarkin V, Joye SB (2005) Molecular biogeochemistry of sulphate reduction, methanogenesis and the anaerobic oxidation of methane at Gulf of Mexico cold seeps. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 69:4267–4281

Oremland RS, DesMarais DJ (1983) Distribution, abundance and carbon isotope composition of gaseous hydrocarbons in Big Soda Lake, Nevada: an alkaline meromictic lake. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 47:2107–2114

Oremland RS, Miller LG, Whiticar MJ (1987) Sources and fluxes of natural gases from Mono Lake, California. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 51:2915–2929

Orphan VJ, House CH, Hinrichs K-U, McKeegan KD, DeLong EF (2001a) Methane-consuming archaea revealed by directly coupled isotopic and phylogenetic analysis. Science 293:484–487

Orphan VJ, Hinrichs K-U, Ussler W III, Paull CK, Taylor LT, Sylva SP, Hayes JM, DeLong EF (2001b) Comparative analysis of methane-oxidizing archaea and sulfate-reducing bacteria in anoxic marine sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol 67:1922–1934

Orphan VJ, House CH, Hinrichs K-U, McKeegan KD, DeLong EF (2002) Multiple archaeal groups mediate methane oxidation in anoxic cold seep sediments. PNAS 99:7663–7668

Oude Elferink SJWH, Visser A, Hulshoff Pol LW, Stams AJM (1994) Sulfate reduction in methanogenic bioreactors. FEMS Microbiol Rev 15:119–136

Pancost RD, Sinninghe Damsté JS, de Lint S, van der Maarel MJEC, Gottschal JC, the Medinaut Shipboard Scientific Party (2000) Biomarker evidence for widespread anaerobic methane oxidation in Mediterranean sediments by a consortium of methanogenic Archaea and bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 66:1126–1132

Panganiban AT, Patt TE, Hart W, Hanson RS (1979) Oxidation of methane in the absence of oxygen in lake water samples. Appl Environ Microbiol 37:303–309

Postgate JR (1984) The sulphate-reducing bacteria. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Raghoebarsing AA, Poll A, van de Pas-Schoonen KT, Smolders AJP, Ettwig KF, Rijpstra WIC, Schouten S, Sinninghe Damsté JS, Op den Camp HJM, Jetten MSM, Strous M (2006) A microbial consortium couples anaerobic methane oxidation to denitrification. Nature 440:918–921

Reeburgh WS (1976) Methane consumption in Cariaco Trench waters and sediments. Earth Planet Sci Lett 28:337–344

Reeburgh WS (1980) Anaerobic methane oxidation: rate depth distributions in Skan Bay sediments. Earth Planet Sci Lett 47:345–352

Reeburgh WS (1996) “Soft spots” in the global methane budget. In: Lidstrom ME, Tabita FR (eds) Microbial growth on C, compounds. Kluwer, Dordrecht, pp 334–352

Reeburgh WS, Ward B, Whalen SC, Sandbeck KA, Kilpatrick KA, Kerkhof LJ (1991) Black Sea methane geochemistry. Deep Sea Res 38:S1189–S1210

Reguera G, McCarthy KD, Metha T, Nicoll JS, Tuominen MT, Lovley DR (2005) Extracellular electron transfer via microbial nanowires. Nature 435:1098–1101

Rozendal RA, Hamelers HVM, Euverink GJW, Metz SJ, Buisman CJN (2006) Principle and perspectives of hydrogen production through biocatalyzed electrolysis. Int J Hydrogen Energy 31:1632–1640

Sahinkaya E, Ozkaya B, Kaksonen AH, Puhakka JA (2007) Sulfidogenic fluidized-bed treatment of metal-containing wastewater at 8 and 65C temperatures is limited by acetate oxidation. Water Res 41:2706–2714

Schink B (1997) Energetics of syntrophic cooperation in methanogenic degradation. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 61(20):262–280

Seifert R, Nauhaus K, Blumenberg M, Krüger M, Michaelis W (2006) Methane dynamics in a microbial community of the Black Sea traced by stable carbon isotopes in vitro. Org Geochem 37:1411–1419

Shima S, Thauer RK (2005) Methyl-coenzyme M reductase and the anaerobic oxidation of methane in methanotrophic Archaea. Curr Opin Microbiol 8:643–648

Sibuet M, Olu K (1998) Biogeography, biodiversity and fluid dependence ofdeep-sea cold-seep communities at active and passive margerns. Deep-Sea Res II 45:517–567

Sipma J, Meulepas RJW, Parshina SN, Stams AJM, Lettinga G, Lens PNL (2004) Effect of carbon monoxide, hydrogen and sulfate on thermophilic (55°C) hydrogenogenic carbon monoxide conversion in two anaerobic bioreactor sludges. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 64(3):421–428

Sipma J, Begona Osuna M, Lettinga G, Stams AJM, Lens PNL (2007) Effect of hydraulic retention time on sulfate reduction in a carbon monoxide fed thermophilic gas lift reactor. Water Res 41:1995–2003

Sørensen KB, Finster K, Ramsing NB (2001) Thermodynamic and kinetic requirements in anaerobic methane oxidizing consortia exclude hydrogen, acetate, and methanol as possible electron shuttles. Microb Ecol 42:1–10

Stadnitskaia A, Muyzer G, Abbas B, Coolen MJL, Hopmans EC, Baas M, van Weering TCE, Ivanov MK, Poludetkina E, Sinninghe Damste JS (2005) Biomarker and 16S rDNA evidence for anaerobic oxidation of methane and related carbonate precipitation in deep-sea mud volcanoes of the Sorokin Trough, Black Sea. Mar Geol 217:67–96

Stadnitskaia A, Ivanov MK, Blinova V, Kreulen R, van Weering TCE (2006) Molecular and carbon isotopic variability of hydrocarbon gases from mud volcanoes in the Gulf of Cadiz, NE Atlantic. Mar Pet Geol 23:281–296

Stams AJM (1994) Metabolic interactions between anaerobic bacteria in methanogenic. Environ Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 66:271–294

Stams AJM, Plugge CM, de Bok FAM, van Houten BHGW, Lens P, Dijkman H, Weijma J (2005) Metabolic interactions in methanogenic and sulfate-reducing bioreactors. Wat Sci Technol 52(1–2):13–20

Stams AJM, de Bok FA, Plugge CM, van Eekert MH, Dolfing J, Schraa G (2006) Exocellular electron transfer in anaerobic microbial communities. Environ Microbiol 8:371–382

Stucki G, Hanselmann KW, Hürzeler RA (1993) Biological sulfuric acid transformation: reactor design and process optimization. Biotechnol Bioeng 41:303–315

Sultan N, Cochonat P, Foucher J-P, Mienert J (2003) Effect of gas hydrates melting on seafloor slope stability. Mar Geol 213:379–401

Thauer RK, Shima S (2008) Methane as fuel for anaerobic organisms. Ann NY Acad Sci 1125:158–170

Thiel V, Peckmann J, Seifert R, Wehrung P, Reitner J, MIchaelis W (1999) Highly isotopically depleted isoprenoids: molecular markers for ancient methane venting. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 63:3959–3966

Thiel V, Peckman J, Richnow HH, Luth U, Reitner J, Michaelis W (2001) Molecular signals for anaerobic methane oxidation in Black Sea seep carbonates and microbial mat. Mar Chem 73:97–112

Thomsen TR, Finster K, Ramsing NB (2001) Biogeochemical and molecular signatures of anaerobic methane oxidation in a marine sediment. Appl Environ Microbiol 67(4):1646–1656

Treude T, Boetius A, Knittel K, Wallmann K, Jørgensen BB (2003) Anaerobic oxidation of methane above gas hydrates at Hydrate Ridge, NE Pacific Ocean. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 264:1–14

Treude T, Krüger M, Boetius A, Jørgensen BB (2005a) Environmental control on anaerobic oxidation of methane in the gassy sediments of Eckernförde Bay (German Baltic) Limnol. Oceanogr 50:1771–1786

Treude T, Niggeman J, Kallmeyer J, Wintersteller P, Schubert CJ, Boetius A, Jørgensen BB (2005b) Anaerobic oxidation of methane and sulfate reduction along the Chilean continental margin. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 69(11):2767–2779

Treude T, Orphan V, Knittel K, Gieseke A, House CH, Boetius A (2007) Consumption of Methane and CO2 by Methanotrophic Microbial mats from gas seeps of the anoxic Black sea. Appl Environ Microbiol 73(7):2271–2283

Valentine DL (2002) Biogeochemistry and microbial ecology of methane oxidation in anoxic environments: a review. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 81:271–282

Vallero MVG, Lettinga G, Lens PNL (2005) High rate sulfate reduction in a submerged anaerobic membrane bioreactor (SAMBaR) at high salinity. J Membr Sci 253:217–232

van Bodegom PM, Stams AJM (1999) Effects of alternative electron acceptors and temperature on methanogenesis in rice paddy soils. Chemosphere 39:167–182

van den Bosch PLF (2008) Biological sulfide oxidation by natron-alkaliphilic bacteria. PhD thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen

van der Drift A, van Doorn J, Vermeulen JW (2001) Ten residual biomass fuels for circulating fluidized-bed gasification. Biomass Bioenergy 20:45–56

van Houten RT (1996) Biological sulphate reduction with synthesis gas. PhD Thesis, Wageningen University, The Netherlands

van Houten RT, Hulshoff Pol LW, Lettinga G (1994) Biological sulphate reduction using gas-lift reactors fed with hydrogen and carbon dioxide as energy and carbon source. Biotechnol Bioengin 44:586–594

van Houten RT, Elferink SJWHO, van Hamel SE, Pol LWH, Lettinga G (1995a) Sulphate reduction by aggregates of sulphate-reducing bacteria and homo-acetogenic bacteria in a lab-scale gas-lift reactor. Bioresour Technol 54:73–79

van Houten RT, van der Spoel H, van Aelst AC, Hulshoff Pol LW, Lettinga G (1995b) Biological sulfate reduction using synthesis gas as energy and carbon source. Biotechnol Bioengin 50:136–144

van Houten RT, Yun SY, Lettinga G (1997) Thermophilic sulphate and sulphite reduction in lab-scale gas-lift reactors using H2 and CO2 as energy and carbon source. Biotechnol Bioengin 55:807–814

van Houten BHGW, Roest K, Tzeneva VA, Dijkman H, Smidt H, Stams AJM (2006) Occurrence of methanogenesis during start-up of a full-scale synthesis gas-fed reactor treating sulfate and metal-rich wastewater. Water Res 40:553–560

Veeken AHM, Akoto L, Hulshoff Pol LW, Weijma J (2003) Control of the sulfide (S2−) concentration for optimal zinc removal by sulfide precipitation in a continuously stirred tank reactor. Water Res 37:3709–3717

Waki M, Suzuki K, Osada T, Tanaka Y (2004) Methane-dependent denitrification by a semi-partitioned reactor supplied separately with methane and oxygen. Bioresour Technol 96:921–927

Wallmann K, Drews M, Aloisi G, Bohrmann G (2006) Methane discharge into the Black Sea and the global ocean via fluid flow through submarine mud volcanoes. Earth Planet Sci Lett 248:544–559

Wegener G, Niemann H, Elvert M, Hinrichs K-U, Boetius A (2008) Assimilation of methane and inorganic carbon by microbial communities mediating the anaerobic oxidation of methane. Environ Microbiol 10(9):2287–2298

Weijma J, Stams AJM, Hulshoff Pol LW, Lettinga G (2000) Thermophilic sulfate reduction and methanogenesis with methanol in a high rate anaerobic reactor. Biotechnol Bioenring 67(3):354–363

Weijma J, Copini CFM, Buisman CJN, Schulz CE (2002) Biological recovery of metals, sulfur and water in the mining and metallurgical industry. In: Lens P (ed) Water recycling, resource recovery in industry: analysis, technologies, implementation. IWA, London, pp 605–622

Whiticar MJ (1996) Isotope tracking of microbial methane formation and oxidation. Mitt Internat Verein Limnol 25:39–54

Widdel F, Rabus R (2001) Anaerobic biodegradation of saturated and aromatic hydrocarbons. Curr Opin Biotech 12:259–276

Widdel F, Musat F, Knittel K, Galushko A (2007) Anaerobic degradation of hydrocarbons with sulphate as electron acceptor. In: Barton LL, Hamilton WA (eds) Sulphate-reducing bacteria. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 265–303

Wu Z, Zhou H, Peng X, Chen G (2006) Anaerobic oxidation of methane: geochemical evidence from pore-water in coastal sediments of Qi’ao Island (Pearl River Estuary), southern China. Chin Sci Bull 51(16):2006–2015

Xin J-J, Cui J-R, Niu J-Z, Hua S-F, Xia C-G, Li S-B, Zhu L-M (2004) Production of methanol from methane by methanotrophic bacteria. Biocatal Biotransform 22(3):225–229

Yamamoto S, Alcauskas JB, Crozier TE (1967) Solubility of methane in distilled water and seawater. J Chem Eng Data 21(1):78–80

Zehnder AJB, Brock TD (1979) Methane formation and methane oxidation by methanogenic bacteria. J Bacteriol 137(1):420–432

Zehnder AJB, Brock TD (1980) Anaerobic methane oxidation: occurrence and ecology. Appl Environ Microbiol 39(1):194–204

Acknowledgments

This work was part the Anaerobic Methane Oxidation for Sulfate Reduction project supported by the Dutch ministries of Economical affairs, Education, culture and science and Environment and special planning as part their EET program, and was co-funded by King Abdullah University of Science and Technology through the SOWACOR project.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Meulepas, R.J.W., Stams, A.J.M. & Lens, P.N.L. Biotechnological aspects of sulfate reduction with methane as electron donor. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol 9, 59–78 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11157-010-9193-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11157-010-9193-8