Abstract

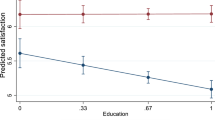

Using data from the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems, this paper examines differences between West and East European countries in their levels of satisfaction with the way democracy works. Compared to East European countries, satisfaction levels were considerably higher in Western countries (West Europe, North America, and Oceania). Moreover, there was considerably greater inequality in the distribution of satisfaction in East European, compared to Western, countries. When these facts were combined to construct “equity-sensitive” satisfaction averages, the gap between Western countries and East European countries was even greater than suggested by a comparison of average satisfaction levels. This raised the question of why satisfaction levels varied so markedly between these two sets of countries. A logit model suggested that a number of factors were important for determining whether people were satisfied with the way democracy worked in their countries. While there was a difference between Western countries and East European countries in their endowments of these satisfaction-inducing factors (income, gender, participation, education, among others), when the equations were estimated separately for the Western countries and East European countries, the coefficient responses associated with several of these factors also differed markedly between the two groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Indeed, Cannache et al. (2001) have called into question the entire concept of voter satisfaction.

The countries were: Australia, Belarus, Belgium, Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Great Britain, Hong Kong, Hungary, Iceland, Israel, Japan, Korea, Lithuania, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, Thailand, Ukraine, and the United States.

In the language of economics, the two situations would yield the same hypothetical level of social welfare, i.e., be ‘welfare equivalent’.

A related question was: Thinking of the last election in [country], where would you place it on a scale of one to five, where ONE means that the last election was conducted fairly and FIVE means that the last election was conducted unfairly?

It should be pointed out, parenthetically, that being dissatisfied with the democratic process raises issues which are broader than the fairness of elections. A related question asked by CSES was: thinking of the last election in [your country], where would you place it on a scale of one to five, where ONE means that the last election was conducted fairly and FIVE means that the last election was conducted unfairly? Of the 51,590 respondents who answered this question, 3,490 respondents (7 %) returned “5” as their answer to this question. In several countries there was inconsistency between being satisfied with the democratic process and views about electoral fairness: in Peru, for example, 45 % of respondents thought that the 2000 election had been conducted unfairly but 18 % were not at all satisfied with the democratic process; in Thailand, 24 % of respondents thought that the 2001 election had been conducted unfairly but only 4 % were not at all satisfied with the democratic process.

In fact we reversed the original CSES assignment of 1 for maximum satisfaction and 4 for maximum dissatisfaction.

The changes in the probability of the outcome (in this case, “satisfied” with the way democracy works), following a change in the value of a variable, is the marginal probability associated with that variable.

Excluding Israel.

The t value was 1.60 with Pr>|t|=11.1.

However, one cannot rule out reverse causation, namely that people voted because they were satisfied rather than people were satisfied because they voted.

Compared to the residual category, respondents who were “not in the labor force” (including the permanently disabled).

However, in the Western European countries studied here only the United States had an elected head of state.

Compared to the coefficient responses of East European respondents, the coefficient responses of Western countries respondents were more conducive to satisfaction.

References

Anand, S., & Sen, A. (1997). Concepts of human development and poverty: a multidimensional perspective. Human Development Report 1997 Papers. New York: UNDP.

Atkinson, A. B. (1970). On the measurement of inequality. Journal of Economic Theory, 2, 244–263.

Bauch, P. A., & Goa, H. (2000). Contributions of parents’ school opinions and reasons for their willingness to support catholic high schools: a structural model. Paper presented at American Educational Research Association Annual Conference. New Orleans, 24–28 April.

Borooah, V. K., & Iyer, S. (2005). The decomposition of inter-group differences in a logit model: extending the Blinder-Oaxaca approach with an application to school enrolment in India. Journal of Economic and Social Measurement, 30, 279–293.

Borooah, V. K. (2009). Comparing levels of job satisfaction in the countries of western and eastern Europe. International Journal of Manpower, 30, 304–325.

Cannache, D., Mondak, J. J., & Seligson, M. A. (2001). Meaning and measurement in cross-national research on satisfaction with democracy. Public Opinion Quarterly, 65, 506–528.

Conyers, J. G. (2000). When status quo won’t do: school district 15. School Administrator, 57, 22–27.

Easton, D. (1965). A framework for political analysis. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Farrell, D. M., & McAllister, I. (2006). Voter satisfaction and electoral systems: does preferential voting in candidate-centred systems make a difference? European Journal of Political Research, 45, 723–749.

Frank, R. H. (1997). The frame of reference as a public good. Economic Journal, 107, 1832–1847.

Frank, R. H. (1999). Luxury fever: money and happiness in an era of excess. Princeton/Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Karp, J. A., Banducci, S. A., & Shaun Bowler, S. (2003). To know it is to love it? Satisfaction with democracy in the European Union. Comparative Political Studies, 36, 271–292.

Layard, R. (2006). Happiness: lessons from a new science. London: Penguin.

Lipset, S. M. (1966). Political man. London: Mercury.

Norris, P. (2000). A virtuous circle? Political communications in post-industrial democracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nielsen, H. S. (1998). Discrimination and detailed decomposition in a logit model. Economics Letters, 61, 115–120.

Oaxaca, R. (1973). Male-female wage differentials in urban labor markets. International Economic Review, 14, 693–709.

Paldam, M. (1979). Is there an election cycle? A comparative study of national accounts. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 81, 323–342.

Paldam, M. (1981). A preliminary survey of the theories and findings on vote and popularity functions. European Journal of Political Research, 9, 181–199.

Paldam, M. (1991). How robust is the vote function? A study of seventeen countries over four decades. In H. Norpoth, M. S. Lewis-Beck, & J.-D. Lafay (Eds.), Economics and politics: the calculus of support (pp. 9–31). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Paldam, M. (2003). Are vote and popularity functions economically correct? In F. Schneider & C. Rowley (Eds.), Encyclopaedia of public choice (Vol. 1, pp. 49–59). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Paldam, M., & Skott, P. (1995). A rational-voter explanation of the cost of ruling. Public Choice, 83, 159–172.

Sapiro, V., & Shively, W. P. (2004). Comparative study of electoral systems, 1996–2001. Center for Political Studies, University of Michigan. Ann Arbor: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research.

Sen, A. K. (1998). On economic inequality. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Warr, P. B. (1999). Well-being and the workplace. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: the foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 392–412). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Acknowledgements

The data used in this paper are from the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems—Module 1 (1996–2001) available from the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR), http://www.icpsr.umich.edu. An earlier version was presented at the Annual Conference of the European Public Choice Society, Izmir, April 2010 and thanks are due to participants for their comments. We are very grateful to the Associate Editor (Europe) and three anonymous referees for comments that have substantially improved the paper. However, we are entirely responsible for the paper’s deficiencies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Borooah, V.K., Katos, A.B. & Katsouli, E. Inter-country differences in voter satisfaction with the democratic process: a study of world elections. Public Choice 157, 569–584 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-013-0134-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-013-0134-2