Abstract

Due to their hybrid nature, German adjectival participles display properties of both adjectives and verbs. In particular, their verbal behaviour is evidenced by the restricted availability of manner and other event-related modifiers. I propose that German adjectival participles denote degrees (state kinds), which accounts for their adjectival behaviour, and that an adjectival passive construction refers to the instantiation of a consequent state kind of an event kind, which accounts for the verbal properties. Event-related modifiers that name event participants, i.e. phrases headed by by or with, are analysed in terms of pseudo-incorporation. This account is motivated by the fact that the nouns in such phrases display properties of pseudo-incorporated nouns, such as discourse opacity and the requirement of naming an institutionalised or conventionalised activity or state, together with the verb/participle these phrases incorporate into. The restrictions on event-related modification, then, follow from general restrictions on kind modification and on pseudo-incorporation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

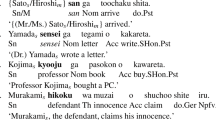

In German, adjectival passives are morphologically distinct from verbal passives, as they combine a past participle with inflected forms of sein ‘be’ (cf. (1)), rather than werden ‘become’ (cf. (2)).

McIntyre (2013) discusses a class of non-resultative adjectival participles, his ‘situation-in-progress’ participles, which presumably subsume such participles derived from stative predicates.

In her account of adjectival passives in Hebrew, which argues for the complete absence of an event, Meltzer-Asscher (2011) is more precise and proposes a meaning postulate, according to which event-related modification triggers the reconstruction of an event that is interpreted as causing the state denoted by the adjective. A problem with this account is that we would expect all event-related modifiers to be possible again, or at least all equally dispreferred, contra the facts: there is a clear split between acceptable and unacceptable ones, as in (3) vs. (4).

This proposal has been taken up by Gese (2011), who provides additional experimental evidence that we are dealing with event kinds rather than event particulars.

In Sect. 5, I will discuss apparent counter-examples to the claim that spatial PPs are not possible with adjectival passives. Upon closer inspection, these acceptable PPs will turn out not to spatially locate an event particular, but rather to specify the manner of the event kind, and thus to derive an event subkind, similar to (11) below.

Recall from the discussion around (5) that we are only concerned with event-related modifiers here; things are different with state-related modifiers (cf. Gehrke 2013).

As pointed out by Ai Kubota (p.c.), this raises the question whether the examples in (13) improve if we replace the respective nominals by indefinites or bare ones. In Sect. 5, I will show that this will not necessarily improve these examples, and we will see that there are two things that play a role. First, the nominal may not refer to a particular entity in the discourse (as described in Gehrke 2013), and second (to be elaborated in that section) the modifier has to derive a well-established event kind.

Olav Mueller-Reichau (p.c.) points out that the generality of these properties might be too strong in light of data like the following:

-

(i)

He also points out that sometimes even proper names are possible in by- and with-phrases, which at first sight is a problem for claiming that the nominals cannot be strongly referential. I will have more to say about proper names in Sect. 5.

My intuition concerning (i-a) is that the continuation is rather special in that it creates a surprise effect, instead of being a run-of-the-mill continuation of the first sentence. However, I do not know how to analyse sentences like these precisely, and leave them for future research. All in all, such examples are marginal, so I assume that the overall claim that pronominal anaphora is not possible can be maintained. (i-b), in turn, does not make reference to a specific blond child in the discourse. Rather, in the conceptual world of Nazis there is (unfortunately) an established kind ‘blond child’ and this kind description can appear in event-related modifiers of adjectival passives. In essence, then, the modifier is a kind rather than a token modifier, hence it is not an exception to the claim that token modification is not available.

-

(i)

Under the assumption that a similar difference between adjectival and verbal passives holds for Spanish, which also morphologically distinguishes between the two, corroborating evidence for this observation comes from a corpus study (Gehrke and Marco 2014). In particular, we found significant differences in the type of complements with by-phrases in adjectival and verbal passives, the former displaying a higher occurrence of bare nouns and indefinite determiners and a general ban on pronouns, definite determiners, and proper names.

Arguments in favour of its absence from syntax include the impossibility of implicit agents in adjectival passives to control into purpose clauses, as well as the absence of a disjoint reference effect (e.g. Kratzer 1994, 2000) (but see also McIntyre 2013; Bruening 2014; Alexiadou et al. 2014). Arguments in favour of its conceptual presence come from the (albeit limited) availability of by-phrases, instruments and manner adverbs, which has been addressed in Sect. 2. For a more detailed discussion of external arguments of the underlying verb in adjectival passives, see Gehrke (2013).

McIntyre (2013) dubs this the ‘Direct Argument Generalisation’, according to which adjectival participles always modify nominals corresponding to direct objects (unaccusative subjects) of their related verbs. An open question is whether also unaccusative verbs can be good inputs then. McIntyre and Bruening (2014) as well as Gese et al. (2011) argue for English and German, respectively, that they are. However, McIntyre and Bruening only discuss attributive uses of participles derived from unaccusative verbs, i.e. participles in prenominal position (i-a). Many of these participles cannot be used in predicative position, though (i-b).

-

(i)

Hence, an alternative analysis of the prenominal participles in terms of reduced relative clauses of verbal rather than adjectival constructions is possible (see Rapp 2001; Sleeman 2011, for such a proposal). This analysis might even be preferred, given that a modifier like recently cannot pick up the time of the event with adjectival passives, as we saw in Sect. 2, example (6), unlike what we find in (i-a), where the departure / escape has taken place recently (similar data from Spanish is discussed in Zagona 2015).

In German it is difficult to test whether such participles can appear in predicative position (and thus be adjectival). This is so because the combination of be and participle is potentially ambiguous between a perfect and an adjectival passive construction, since unaccusative verbs select for the be-auxiliary in the perfect. Gese et al. (2011) propose that temporal adverbials disambiguate between these two (alleged) readings, with one kind of temporal adverbial locating the event in the past (ii-a), thus selecting for a perfect construction, and another type of temporal adverbial locating the state in the present (ii-b), thus selecting for an adjectival passive construction (claim and examples from Gese et al. 2011).

-

(i)

However, the temporal adverbial in (ii-b) cannot be seen as disambiguating, since such adverbials are also acceptable with perfects that select a have-auxiliary, which are thus unambiguously perfect and not adjectival passive constructions:

-

(i)

Even if the first sentence might not sound acceptable in English, in German it is perfectly fine and means something like ‘Otto finished reading the book two weeks ago and now knows it / is familiar with it’. Hence, the fact that perfect constructions make available a state that can be modified temporally does not preclude it from also having an event that can be temporally modified (see also von Stechow 2002), unlike what we find with adjectival passives (see Sect. 2). I will leave the question as to whether or not unaccusative verbs are good inputs to German adjectival passives for future research.

-

(i)

Common unaccusativity diagnostics for German are: be-auxiliary selection, the possibility of using the past participle as an attribute, the impossibility to be used in impersonal passives, the impossibility to derive agent nominals (e.g. Haider 1984). These diagnostics cannot be applied to German adjectival participles because you generally cannot derive an impersonal passive, a participle, or a nominal from an (already derived) adjectival participle.

This assumption is widespread also cross-linguistically; see, for instance, Meltzer-Asscher (2011) for a recent proposal for Hebrew, who argues that the input has to be ‘telic’.

The inchoativity of psych predicates has recently been discussed by Marín and McNally (2011), who argue, based on data from Spanish, that inchoativity is different from telicity or (temporal) change of state. In particular, they discuss Spanish reflexive psych predicates, which are object experiencer verbs, and precisely these are stative predicates that allow adjectival passive formation (see also Sánchez Marco 2012). While I agree with Marín and McNally that inchoativity is not identical to telicity, I adopt a broader notion of change of state to also include non-temporal change (as discussed below), which aligns these predicates with change of state predicates. Adjectival and verbal passives of (Spanish) psych predicates are discussed in more detail in Gehrke and Marco (2015).

Experimental support for the idea that the state described by an adjectival passive is evaluated against a contrasting state comes from Claus and Kriukova (2012). In particular, they tested German native speakers for the mental availability of contrasting states by measuring picture-identification latencies (e.g. showing the picture of a closed door after an adjectival passive of the type Die Tür is geöffnet. ‘The door is opened.’). They found a higher availability of contrasting states after reading a sentence with an adjectival passive than after reading a corresponding sentence with an adjective.

This is reminiscent of the use of directional PPs in contexts that do not describe a temporal change of location, e.g. the bridge into San Francisco. Such uses have been discussed in detail in Fong (1997), who proposes a general account in terms of Löbner’s (1989) phase quantification, a general notion that is independent of temporal or spatial interpretations and could capture the mere opposition between two opposite states in the case of adjectival passives as well. However, I will continue to use become.

As pointed out by Andrew McIntyre (p.c.), the elements genug ‘enough’ and fertig ‘ready/done’ in (28-c) are not necessarily secondary resultative predicates, but I believe they fulfill similar functions. Especially fertig is a very productive element in German that one can add to most verb phrases to signal that a particular action has been sufficiently performed. I will leave the precise analysis of elements like these for future research.

The latter examples are acceptable under the ‘job-is-done’-reading, which will be discussed in the following section.

Rappaport Hovav and Levin argue that the notion of result should not be equated with the notion of telicity, but rather with the notion of scalar change.

To be more precise, Vendler (1957) classified the intransitive uses and the transitive uses with mass nouns or bare plurals (–sqa or non-quantized nominals in Verkuyl 1972; Krifka 1989, respectively) in internal argument position as activities, and the transitive uses with (+sqa / quantized) nominals as accomplishments; with ‘pure’ activities, in contrast, the nature of the internal argument does not play an aspectual role (see Rothstein 2004, for further discussion).

Nothing is said as to whether this requirement can be derived from some more general pragmatic principle. It is only stated that it is necessary to situate the ad hoc property in the subject’s property space (see also Maienborn 2007a, 102f.), so I assume it has to do with Barsalou’s notion of ad hoc properties. In Maienborn (2009, 42), Barsalou’s ad hoc categories are described as ‘goal-derived categories that are created spontaneously for use in more or less specialized contexts. Under this perspective adjectival passives may be seen as a means to extend and contextualize a concept’s property space with respect to contextually salient goals.’

Thanks to Ai Kubota for pointing this out.

It should be noted, however, that many speakers do not even accept (33-b) and (33-c) with the additional context, whereas (33-a) is accepted by everyone. I take this as an additional indication that the input restrictions are hard-wired into the grammar.

This characterisation is rather informal but could be formalised along the lines of Kennedy and McNally (2005), Kennedy and Levin (2008), Kennedy (2012). In particular, the relevant property ascribed to the theme should be seen as a specific degree on a given scale, which is associated with the degree a theme normally has at the end of an event involving scalar change (temporal or spatial); this is the standard of comparison associated with the respective measure of change function (the scalar maximum if the input scale has such a maximum element, otherwise contextually fixed).

Furthermore, it is not straightforward that this characterisation and in particular the formalisation in 42 covers the stative inputs, since with these predicates we should not have an event variable, rather only an opposition between two states on a scale. We could think of the (causing) event in this case as not being lexically specified whereas the lexical predicate specify the meaning of the state, or we could follow Marín and McNally’s (2011) formalisation of inchoativity, built on Piñón’s (1997) analysis of boundary happenings. I will leave the precise analysis of the stative predicates for future research.

I depart from Gehrke (2013) in representing the input requirements of adjectival passives by become (as in Gehrke 2012). This point was orthogonal to the topic of Gehrke (2013), which simply followed McIntyre (2013) in representing this by a cause-relation (as well as in labelling the agent or causer Initiator). If we understand cause in the sense of Kratzer’s (2005) events of causing other events in a chain of events bringing about a state, it becomes quite similar to become, as employed here. As in Gehrke (2013) I will represent the Initiator argument as part of the lexical semantics of the verb, not as severed from the verb (in the sense of Kratzer 1996), though nothing hinges on this (see Alexiadou et al. 2014, for a proposal that employs Voice).

The relevance of assuming event kinds from the start came about after discussion with Olav Mueller-Reichau.

Note that McIntyre (2013) and Bruening (2014) collapse the tasks I distribute over Prt (passivisation, existential quantification over the external argument) and Adj (stativisation, externalisation of the internal argument) into one passive Voice head, which they label Prt and Adj, respectively. The dissociation of passivisation and adjectivisation is motivated by the idea that at the point of participle formation both verbal and adjectival participles are alike, and more importantly, by the need for an attachment site for event-related modification before adjectivisation, which renders the event inaccessible for further modification (see Gehrke 2013, for further discussion).

Olav Mueller-Reichau provides an alternative acceptable example with a by-phrase, though:

-

(i)

He points out that in this example, the by-phrase does not name the author of a work (a real agent) but rather the worker or the tool in a factory (which is thus more like an instrument). This supports the overall conclusion that instruments (in a broader sense) can name the manner of an event.

-

(i)

As pointed out by Olav Mueller-Reichau (p.c.), the job-is-done reading (recall Sect. 3) does not require well-establishedness, as illustrated by his examples in (i).

-

(i)

There might still be the requirement on having weakly referential noun phrases in such modifiers though. Since I leave aside the job-is-done reading as pragmatically licensed, I do not have much more to say about examples like these.

-

(i)

Pseudo-incorporated nouns are also commonly characterised as number-neutral. The singular bare noun pis in (i), for example, does not restrict the apartment-search to exactly one apartment, but can involve more apartments as suggested by the continuation.

-

(i)

Dayal (2011) derives the apparent number neutrality of the noun from an overall interaction with grammatical aspect, rather than ascribing this property to the noun itself. Since number neutrality is thus a debated property of pseudo-incorporation, I will not discuss it further here.

-

(i)

Another property they share with incorporated nouns is that they typically appear in object position, in subject position only in generic sentences:

-

(i)

-

(i)

Note that in our initial example, the participle is geschlossen, whereas in example (65), the participles is verschlossen, and both are translated as ‘closed’. I take both to involve a change of state (from non-closed to closed), but it seems to me that there is a slight semantic difference between the two, in the sense that the prefix ver- in the latter adds a meaning component that the closing is hindering something from being open, whereas the former one is neutral in this respect. Since I believe that this subtle semantic difference is orthogonal to the current account, I will gloss over it here.

References

Aguilar-Guevara, Ana 2014. Weak definites: Semantics, lexicon and pragmatics. Vol. 360 of LOT Dissertation Series. Utrecht: LOT.

Aguilar-Guevara, Ana, and Joost Zwarts. 2011. Weak definites and reference to kinds. In Proceedings of SALT 20, eds. Nan Li and David Lutz. Vol. 20, 179–196. Ithaca: CLC Publications.

Alexiadou, Artemis, and Elena Anagnostopoulou. 2008. Structuring participles. In Proceedings of the 26th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics, eds. Charles B. Chang and Hannah J. Haynie, 33–41. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

Alexiadou, Artemis, Berit Gehrke, and Florian Schäfer. 2014. The argument structure of adjectival participles revisited. Lingua 149B: 118–138.

Anagnostopoulou, Elena 2003. Participles and voice. In Perfect explorations, interface explorations 2, eds. Artemis Alexiadou, Monika Rathert, and Arnim von Stechow, 1–36. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Anderson, Curt, and Marcin Morzycki. 2015. Degrees as kinds, this volume. doi:10.1007/s11049-015-9290-z.

Arsenijević, Boban, Gemma Boleda, Berit Gehrke, and Louise McNally. 2014. Ethnic adjectives are proper adjectives. In CLS-46-I the main session: 46th annual meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society, eds. Rebekah Baglini, Timothy Grinsell, Jonathan Keane, Adam Roth Singerman, and Julia Thomas, 17–30. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

Baker, Mark 1988. Incorporation: A theory of grammatical function changing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Barsalou, Lawrence 1983. Ad hoc categories. Memory and Cognition 11: 211–227.

Barwise, Jon, and John Perry. 1983. Situations and attitudes. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Beltrama, Andrea, and M. Ryan Bochnak. 2015. Intensification without degrees cross-linguistically, this volume. doi:10.1007/s11049-015-9294-8.

Boleda, Gemma, Stefan Evert, Berit Gehrke, and Louise McNally. 2012. Adjectives as saturators vs. modifiers: Statistical evidence. In Logic, language and meaning----18th Amsterdam Colloquium, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, December 19–21, 2011, Revised Selected Papers, eds. Maria Aloni, Vadim Kimmelman, Floris Roelofsen, Galit Weidman Sassoon, Katrin Schulz, and Matthijs Westera, 112–121. Dordrecht: Springer.

Borer, Hagit 2005. Structuring sense, vol. II: The normal course of events. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brandt, Margareta 1982. Das Zustandspassiv aus kontrastiver Sicht. Deutsch als Fremdsprache 19: 28–34.

Bruening, Benjamin 2013. By phrases in passives and nominals. Syntax 16(1): 1–41.

Bruening, Benjamin 2014. Word formation is syntactic: Adjectival passives in English. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 32(2): 363–422.

Carlson, Greg 2003. Weak indefinites. In From NP to DP, eds. Martine Coene and Yves D’hulst, 195–210. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Carlson, Greg 1977. Reference to kinds in English. PhD thesis, University of Massachusetts at Amherst, published in 1980 by Garland, New York

Carlson, Greg, Rachel Sussman, Natalie Klein, and Michael Tanenhaus. 2006. Weak definite noun phrases. In NELS 36: Proceedings of the 36th annual meeting of the North East Linguistic Society, eds. Christopher Davis, Amy Rose Deal, and Youri Zabbal, 179–196. Amherst: GLSA.

Carlson, Greg 2009. Generics and concepts. In Kinds, things, and stuff: Mass terms and generics, ed. Francis Jeffry Pelletier, 16–35. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chierchia, Gennaro 1998. Reference to kinds across languages. Natural Language Semantics 6: 339–405.

Chung, Sandra, and William Ladusaw. 2003. Restriction and saturation. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Cieschinger, Maria, and Peter Bosch. 2011. Seemingly weak definites: German preposition-determiner contractions. Paper presented at the SuB Satellite Workshop on Weak Referentiality, Utrecht University, September 2011.

Cinque, Guglielmo 1990. Ergative adjectives and the lexicalist hypothesis. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 8: 1–39.

Claus, Berry, and Olga Kriukova. 2012. Interpreting adjectival passives: Evidence for the activation of contrasting states. In Empirical approaches to linguistic theory: Studies of meaning and structure, eds. Britta Stolterfoht and Sam Featherston, 187–206. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Davidson, Donald 1967. The logical form of action sentences. In The logic of decision and action, ed. Nicholas Resher, 81–95. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Dayal, Veneeta 2004. Number marking and (in)definiteness in kind terms. Linguistics and Philosophy 27: 393–450.

Dayal, Veneeta 2011. Hindi pseudo-incorporation. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 29(1): 123–167.

Dayal, Veneeta 2013. Standard complementation, pseudo-incorporation, compounding. Paper presented at the DGfS workshop The Syntax and Semantics of Pseudo-Incorporation, Potsdam, March 2013.

Dowty, David 1979. Word meaning and Montague grammar: The semantics of verbs and times in generative semantics and in Montague’s PTQ. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Embick, David 2004. On the structure of resultative participles in English. Linguistic Inquiry 35(3): 355–392.

Espinal, M. Teresa, and Louise McNally. 2011. Bare singular nominals and incorporating verbs in Spanish and Catalan. Journal of Linguistics 47: 87–128.

Farkas, Donka, and Henriëtte de Swart. 2003. The semantics of incorporation: From argument structure to discourse transparency. Stanford: Center for the Study of Language and Information.

Fong, Vivienne 1997. The order of thing: What directional locatives denote. PhD thesis, Stanford University.

Gawron, Jean Mark 2009. The lexical semantics of extent verbs, ms. San Diego State University

Gehrke, Berit 2008. Ps in motion: On the syntax and semantics of P elements and motion events. Vol. 184 of LOT Dissertation Series. Utrecht: LOT.

Gehrke, Berit 2011. Stative passives and event kinds. In Sinn und Bedeutung 15, eds. Ingo Reich, Eva Horch, and Dennis Pauly, 241–257. Saarbrücken: Universaar—Saarland University Press.

Gehrke, Berit 2012. Passive states. In Telicity, change, and state: A cross-categorial view of event structure, eds. Violeta Demonte and Louise McNally, 185–211. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gehrke, Berit 2013. Still puzzled by adjectival passives? In Syntax and its limits, eds. Raffaella Folli, Christina Sevdali, and Robert Truswell, 175–191. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gehrke, Berit, and Marika Lekakou. 2013. How to miss your preposition. Studies in Greek Linguistics 33: 92–106.

Gehrke, Berit, and Cristina Marco. 2014. Different by-phrases with adjectival passives: Evidence from Spanish corpus data. Lingua B149: 188–214.

Gehrke, Berit, and Cristina Marco. 2015, to appear. Las pasivas psicológicas. In Los predicados psicológicos, ed. Rafael Marín. Visor, Madrid.

Gehrke, Berit, and Louise McNally. 2011. Frequency adjectives and assertions about event types. In Proceedings of SALT 19, eds. Ed Cormany, Satoshi Ito, and David Lutz, 180–197. Ithaca: CLC Publications.

Gehrke, Berit, and Louise McNally. 2015, to appear. Distributional modification: The case of frequency adjectives. Language.

Gese, Helga 2010. Implizite Ereignisse beim Zustandspassiv. Paper presented at the workshop ‘Zugänglichkeit impliziter Ereignisse’, University of Tübingen, July 2010.

Gese, Helga 2011. Events in adjectival passives. In Sinn und Bedeutung 15, eds. Ingo Reich, Eva Horch, and Dennis Pauly, 259–273. Saarbrücken: Universaar—Saarland University Press.

Gese, Helga, Claudia Maienborn, and Britta Stolterfoht. 2011. Adjectival conversion of unaccusatives in German. Journal of Germanic Linguistics 23(2): 101–140.

Ginzburg, Jonathan 2005. Situation semantics: The ontological balance sheet. Research on Language and Computation 3(4): 363–389.

Gumiel-Molina, Silvia, Norberto Moreno-Quibén, and Isabel Pérez-Jiménez. 2015. Comparison classes and the relative/absolute distinction: A degree-based compositional account of the ser/estar alternation in Spanish, this volume. doi:10.1007/s11049-015-9284-x.

Haider, Hubert 1984. Was zu haben ist und was zu sein hat. Papiere zur Linguistik 30(1): 22–36.

Halle, Morris, and Alec Marantz. 1993. Distributed morphology and the pieces of inflection. In The view from building 20: Essays in honor of Sylvain Bromberger, eds. Kenneth Hale and Samuel Jay Keyser, 111–176. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Higginbotham, James 1985. On semantics. Linguistic Inquiry 16: 547–593.

Kamp, Hans 1979. Some remarks on the logic of change: Part I. In Time, tense and quantifiers, ed. Christian Rohrer, 135–180. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Kay, Paul 1971. Taxonomy and semantic contrast. Language 47(4): 862–887.

Kennedy, Chris 1999. Projecting the adjective: The syntax and semantics of gradability and comparison. New York: Garland.

Kennedy, Chris 2012. The composition of incremental change. In Telicity, change, state: A cross-categorial view of event structure, eds. Violeta Demonte and Louise McNally, 103–121. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kennedy, Christopher, and Beth Levin. 2008. Measure of change: The adjectival core of degree achievements. In Adjectives and adverbs: Syntax, semantics and discourse, eds. Louise McNally and Christopher Kennedy, 156–182. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kennedy, Christopher, and Louise McNally. 2005. Scale structure and the semantic typology of gradable predicates. Language 81(2): 345–381.

Koontz-Garboden, Andrew 2010. The lexical semantics of derived statives. Linguistics and Philosophy 33(4): 285–324.

Kratzer, Angelika 1994. The event argument and the semantics of Voice, ms. University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Kratzer, Angelika 1996. Severing the external argument from the verb. In Phrase structure and the lexicon, eds. Johann Rooryck and Laurie Zaring, 109–137. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Kratzer, Angelika 2000. Building statives, ms. University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Kratzer, Angelika 2005. Building resultatives. In Event arguments: Foundations and applications, eds. Claudia Maienborn and Angelika Wöllstein, 177–212. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Krifka, Manfred 1989. Nominal reference, temporal constitution and quantification in event semantics. In Semantics and contextual expression, eds. Renate Bartsch, Johan van Benthem, and Peter van Emde Boas, 75–115. Dordrecht: Foris.

Krifka, Manfred 1995. Common nouns in Chinese and English. In The generic book, eds. Gregory N. Carlson and Francis Jeffry Pelletier, 398–411. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Krifka, Manfred, Francis Jeffry Pelletier, Gregory N. Carlson, Alice ter Meulen, Gennaro Chierchia, and Godehard Link. 1995. Genericity: An introduction. In The generic book, eds. Gregory N. Carlson and Francis Jeffry Pelletier, 1–125. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Landman, Meredith, and Marcin Morzycki. 2003. Event-kinds and manner modification. In Proceedings of the thirty-first Western Conference On Linguistics, eds. Nancy Mae Antrim, Grant Goodall, Martha Schulte-Nafeh, and Vida Samiian, 136–147. Fresno: California State University.

Levin, Beth, and Malka Rappaport. 1986. The formation of adjectival passives. Linguistic Inquiry 17: 623–661.

Löbner, Sebastian 1989. German schon–erst–noch: An integrated analysis. Linguistics and Philosophy 12: 167–212.

Maienborn, Claudia 2007a. Das Zustandspassiv: Grammatische Einordnung—Bildungsbeschränkung—Interpretationsspielraum. Zeitschrift für germanistische Linguistik 35: 83–144.

Maienborn, Claudia 2007b. On Davidsonian and Kimian states. In Existence: Semantics and syntax, eds. Ileana Comorovski and Klaus von Heusinger, 107–130. Dordrecht: Springer.

Maienborn, Claudia 2009. Building ad hoc properties: On the interpretation of adjectival passives. In Sinn und Bedeutung 13, eds. Arndt Riester and Torgrim Solstad, 35–49. University of Stuttgart.

Maienborn, Claudia 2011. Strukturausbau am Rande der Wörter: Adverbiale Modifikatoren beim Zustandspassiv. In Sprachliches Wissen zwischen Lexikon und Grammatik, eds. Stefan Engelberg, Anke Holler, and Kristel Proost, 317–343. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Marín, Rafael, and Louise McNally. 2011. Inchoativity, change of state, and telicity. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 29(2): 467–502.

Massam, Diane 2001. Pseudo noun incorporation in Niuean. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 19: 153–197.

McIntyre, Andrew 2013. Adjectival passives and adjectival participles in English. In Non-canonical passives, eds. Artemis Alexiadou and Florian Schäfer, 21–42. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

McNally, Louise, and Gemma Boleda. 2004. Relational adjectives as properties of kinds. In Empirical issues in formal syntax and semantics 5, eds. Olivier Bonami and Patricia Cabdreo Hofherr, 179–196. http://www.cssp.cnrs.fr/eiss5.

Meltzer-Asscher, Aya 2011. Adjectival passives in Hebrew: Evidence for parallelism between the adjectival and verbal systems. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 29: 815–855.

Mithun, Marianne 1984. The evolution of noun incorporation. Language 60: 847–894.

Parsons, Terence 1990. Events in the semantics of English: A study in subatomic semantics. Vol. 19 of Current studies in linguistics series. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Piñón, Christopher 1997. Achievements in an event semantics. In Semantic and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 7, eds. Aaron Lawson and Eun Cho, 273–296. Ithaca: CLC Publications.

Puig Waldmüller, Estela 2008. Contracted preposition-determiner forms in German: Semantics and pragmatics. PhD thesis, Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

Pustejovsky, James 1995. The generative lexicon. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Rapp, Irene 1996. Zustand? Passiv? Überlegungen zum sogenannten “Zustandspassiv”. Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft 15(2): 231–265.

Rapp, Irene 1997. Partizipien und semantische Strukur: Zu passivischen Konstruktionen mit dem 3. Status. Tübingen: Stauffenburg.

Rapp, Irene 2001. The attributive past participle: Structure and temporal interpretation. In Audiatur Vox Sapientiae: A festschrift for Arnim von Stechow, eds. Caroline Féry and Wolfgang Sternefeld, 392–409. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

Rappaport Hovav, Malka, and Beth Levin. 1998. Building verb meanings. In The projection of arguments: Lexical and compositional factors, eds. Miriam Butt and Wilhelm Geuder, 97–134. Stanford: Center for the Study of Language and Information.

Rappaport Hovav, Malka, and Beth Levin. 2010. Reflections on manner/result complementarity. In Syntax, lexical semantics, and event structure, eds. Edit Doron, Malka Rappaport Hovav, and Ivy Sichel, 21–38. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Reichenbach, Hans 1947. Elements of symbolic logic. London: Macmillan & Co.

Rooth, Mats 1992. A theory of focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics 1: 75–116.

Rothstein, Susan 2004. Structuring events: A study in the semantics of lexical aspect. Oxford: Blackwell.

Rotstein, Carmen, and Yoad Winter. 2004. Total adjectives vs. partial adjectives: Scale structure and higher-order modification. Natural Language Semantics 12: 259–288.

Sailer, Manfred 2010. The family of English cognate object constructions. In Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar (HPSG) 17, ed. Stefan Müller, 191–211. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Sánchez Marco, Cristina 2012. Tracing the development of Spanish participial constructions: An empirical study of semantic change. PhD thesis, Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

Sassoon, Galit 2013. Vagueness, gradability and typicality: The interpretation of adjectives and nouns. Leiden: Brill.

Schlücker, Barbara 2005. Event-related modifiers in German adjectival passives. In Sinn und Bedeutung 9, eds. Emar Maier, Corien Bary, and Janneke Huitink, 417–430. Nijmegen: Radboud University.

Scholten, Jolien, and Ana Aguilar-Guevara. 2010. Assessing the discourse referential properties of weak definite NPs. In Linguistics in the Netherlands 2010, eds. Jacqueline van Kampen and Rick Nouwen, 115–128. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Schwarz, Florian 2009. Two types of definites in natural language. PhD thesis, University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Schwarz, Florian 2014. How weak and how definite are weak definites? In Weak referentiality, eds. Ana Aguilar-Guevara, Bert Le Bruyn, and Joost Zwarts, 213–236. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Sleeman, Petra 2011. Verbal and adjectival participles: Position and internal structure. Lingua 121: 1569–1587.

Truswell, Robert 2011. Events, phrases, and questions. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

van Geenhoven, Veerle 1998. Semantic incorporation and indefinite descriptions. Palo Alto: Center for the Study of Language and Information.

Vendler, Zeno 1957. Verbs and times. Philosophical Review 56: 143–160.

Verkuyl, Henk 1972. On the compositional nature of the aspects. Vol. 15 of Foundations of language supplement series. Dordrecht: Reidel.

von Stechow, Arnim 1984. Comparing semantic theories of comparison. Journal of Semantics 3: 1–77.

von Stechow, Arnim 1998. German participles II in Distributed Morphology, ms. University of Tübingen.

von Stechow, Arnim 2002. German seit ‘since’ and the ambiguity of the German perfect. In More than words: A festschrift for Dieter Wunderlich, eds. Barbara Stiebels and Ingrid Kaufmann, 393–432. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

Welke, Klaus 2007. Das Zustandspassiv: Pragmatische Beschränkungen und Regelkonflikte. Zeitschrift für germanistische Linguistik 35: 115–145.

Zagona, Karen 2015. Comparison classes, the relative/absolute distinction and the Spanish ser/estar alternation: Commentary on the paper by Gumiel-Molina, Moreno-Quibén and Pérez-Jiménez, this volume. doi:10.1007/s11049-015-9283-y.

Zamparelli, Roberto 1995. Layers in the determiner phrase. PhD thesis, University of Rochester.

Acknowledgements

This paper grew out of general research on adjectival passives over the past couple of years, and I am indebted to the following people for fruitful discussion and comments: Klaus Abels, Artemis Alexiadou, Elena Anagnostopoulou, Boban Arsenijević, Gennaro Chierchia, Berry Claus, Edit Doron, Helga Gese, Scott Grimm, Ai Kubota, Claudia Maienborn, Rafa Marín, Andrew McIntyre, Louise McNally, Hans-Robert Mehlig, Olav Mueller-Reichau, Antje Roßdeutscher, Cristina Marco, Florian Schäfer, Lisa Travis, Carla Umbach. This work has been supported by a grant to the project JCI-2010-08581 from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, and by a grant to the project FFI2012-34170 from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gehrke, B. Adjectival participles, event kind modification and pseudo-incorporation. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 33, 897–938 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-015-9295-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-015-9295-7