Abstract

Objectives

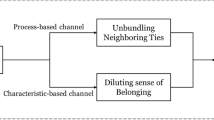

Social disorganization states that neighborhood social ties and shared expectations for informal social control are necessary for the exercise of informal social control actions. Yet this association is largely assumed rather than empirically examined in the literature. This paper examines the relationship between neighborhood social ties, shared expectations for informal social control and actual parochial and public informal social control actions taken by residents in response to big neighborhood problems.

Methods

Using multi-level logistic regression models, we integrate Australian Bureau of Statistics census data with the Australian Community Capacity Study survey data of 1310 residents reporting 2614 significant neighborhood problems across 148 neighborhoods to examine specific informal social control actions taken by residents when faced with neighborhood problems.

Results

We do not find a relationship between shared expectations for informal social control and residents’ informal social control actions. Individual social ties, however, do lead to an increase in informal social control actions in response to ‘big’ neighborhood problems. Residents with strong ties are more likely to engage in public and parochial informal social control actions than those individuals who lack social ties. Yet individuals living in neighborhoods with high levels of social ties are only moderately more likely to engage in parochial informal social control action than those living in areas where these ties are not present. Shared expectations for informal social control are not associated with the likelihood that residents engage in informal social control actions when faced with a significant neighborhood problem.

Conclusion

Neighborhood social ties and shared expectations for informal social control are not unilaterally necessary for the exercise of informal social control actions. Our results challenge contemporary articulations of social disorganization theory that assume that the availability of neighborhood social ties or expectations for action are associated with residents actually doing something to exercise of informal social control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In Australia, the term “suburb” is used to refer to a feature that in the U.S. would be referred to as a “neighborhood”. Suburbs are similar to census tracts in the U.S. context, though in some cases Brisbane suburbs may be larger than census tracts as they are not determined by population. Throughout, we use the more familiar term “neighborhood” to refer to these. The suburbs in Brisbane include those that are adjacent to the main city center and those located in peri-urban areas which have experienced large increases in population growth.

The total number of suburbs in the BSD as of the 2006 census was 429 with a residential population ranging from 15 to 21,001 per suburb. In the U.S., the average size of the census tract is approximately 4000 inhabitants with a minimum of around 1200 residents and a maximum of 8000 residents. In the PHDCN the average size of the neighborhood cluster was 8000. In later analyses of the PHDCN data, these neighborhood clusters were aggregated up to territorial communities with an average of 11,000 respondents. Sampson (2012: 443) reports that the ecometric properties for these larger territorial communities were “virtually equivalent” to the neighborhood clusters. Nonetheless, we assessed whether the results changed due to the inclusion of these large neighborhoods by estimating models excluding cases with more than 10,000 residents and our results were unchanged.

Unlike the United States, Australian cellphone numbers do not align with regional areas and therefore could not be included in the random digit dialing selection process. Longitudinal participants were contacted on their cellphones if they had previously provided that number as a preferred contact number.

The response and cooperation rates were calculated according to American Association for Public Opinion Research guidelines. The response rate was calculated as (complete)/(complete + partial complete + unknown eligibility + eligible non-interview), the cooperation rate was calculated as (complete)/(complete + partial complete + eligible non-interview).

In Australia telephone prefixes indicate the area in which a resident lives. For example in Upper Brookfield the prefix is 3374 whereas in Albany Creek the prefix is 3624. Thus the random digit dialing procedure targeted the prefixes that represented our sample areas.

As with all self-report data, we note that there will be error associated with respondents’ recall.

To assess whether or not simply discussing the problem is a type of action we constructed an alternative measure that did not include the “discussing the problem with neighbors” action. The results were effectively identical.

If they called the police or any other formal agency like government or local council, we coded that response as a public informal social control. If participants reported they had intervened directly or worked with others in their neighborhood to resolve the problem, we coded their response as parochial informal social control. There were too few instances of these other behaviors to model them as a separate category.

There is significant variability in this measure across neighborhoods. We estimated a random effects logit model and found that the variability at the neighborhood level was 1.406 (SE = .239) for public social control, and 4.042 (SE = .934) for parochial social control (both significant at p < .01).

We also assessed whether including multiple observations for a particular person introduced any bias by estimating an additional model that randomly selected one problem reported by each respondent. These ancillary models had somewhat less statistical power, which is unsurprising given the reduced number of observations. Nonetheless, the results of this alternative specification were quite similar to those presented in Table 1, which is reassuring.

The factor analysis approach provides specific weights to each of the variables that compose the measure. These weights are analogous to an item response theory (IRT) approach; see Kamata and Bauer (2008) for the analytical proof that these approaches are identical.

We also estimated ancillary models in which we did not adjust the measures for compositional effects. The alternative measures were highly correlated with those with the adjustments, and the results were very similar with no substantive changes.

We included the following individual level characteristics in the model: household income, education level, length of residence in the neighborhood, female, age, homeowner, marital status (single, widowed, divorced, and married as the reference category), presence of children, and speaking only English in the home. Previous research found very high correlations between measures using a frequentist approach, as we do here, and those using a Bayesian approach (see Steenbeek and Hipp (2011) footnote 12 on page 846).

The following variables were included in the multiple imputation procedure at the individual level: years of education, household income, owner, length of residence, age, gender, presence of children, immigrant background (middle Eastern, Northeast Asian, Southeast Asian, South-central Asian, Southeast European, African), marital status (married, single, divorced, widowed), perception of violence, perception of disorder, perceived collective efficacy, neighborhood social ties, perceived attachment. The following variables were included at the neighborhood level from the Census: percent various immigrant groups (southern European, northern European, middle Eastern, Asian, America, Africa) percent various religious traditions (Christian, Hindu, Islam, Judaism, other) percent various language groups (indigenous, Spanish, Western European), residential instability, median income, unemployment rate, percent with a bachelor’s degree, percent single parent households, percent minorities, population density, percent engaging in volunteer behavior, language heterogeneity, ethnic heterogeneity, religious heterogeneity, percent aged 15–24. The following neighborhood variables from the survey respondents were included: collective efficacy, neighborhood ties, attachment, perceived violence, perceived disorder, average victimization.

We followed Morenoff’s (2003) approach in estimating models including spatial lags of the exogenous variables. Given that the variables were not statistically significant, and the fit of the models were not improved, we do not present those results.

The household measures included in this model were: household income, level of education, length of residence, owner, marital status (widow divorce single), female, age and age squared, presence of children, social ties, social cohesion and expectations for informal social control. Neighborhood-level measures included in the model were: neighborhood social ties, cohesion, expectations for informal social control, median income, residential stability, ethnic heterogeneity, percent indigenous, population density, neighborhood problems per capita.

We also estimated a logistic model in which the outcome was any type of informal social control action (as opposed to none). The coefficients were essentially averages of the parochial and public social results displayed in Table 1. Given our theoretical interest in distinguishing between parochial and public social control (Warner 2007), the combined results are not particularly insightful.

We estimated an additional model that did not include the individual-level measure of informal social control expectations to assess whether it is obscuring the neighborhood-level measure. The results were essentially the same as those in Table 1, suggesting that there is no evidence of obscuring any such effect. We estimated a model that also excluded the individual- and neighborhood-level measures of social ties, and the neighborhood-level measure of expectations of informal social control remained effectively zero.

To assess whether there are collinearity issues with these measures, we also estimated models including each of the variables in Table 2 one at a time (along with the remaining control variables). The results were always the same. Thus, despite the fact that the measures of social ties and cohesion are correlated .36 at the individual level and .66 at the neighborhood level, the results are not an artifact of any undue collinearity.

We assessed this by estimating models on the complete sample in which we included an indicator for high collective efficacy neighborhoods and interactions of this variable with all other variables in the model. A joint significance test was conducted to assess significance of this set of interaction variables (χ 2 = 25.1, df = 21, p = .20 for parochial social control; χ 2 = 30.5, df = 21, p = .08 for public social control.

References

Angeles G, Guilkey DK, Mroz TA (2005) The impact of community-level variables on individual-level: outcomes theoretical results and applications. Sociol Methods Res 34:76–121

Bellair PE (1997) Social interaction and community crime: examining the importance of neighbor networks. Criminology 35(4):677–703

Bellair PE, Browning CR (2010) Contemporary disorganization research: an assessment and further test of the systemic model of neighborhood crime. J Res Crime Delinquency 47(4):496–521

Black D (1984) Toward a general theory of social control. Academic Press Inc, Orlando

Bolland JM, McCallum DM (2002) Neighboring and community mobilization in high poverty inner-city neighborhoods. Urban Aff Rev 38:42–49

Browning CR (2002) The span of collective efficacy: extending social disorganization theory to partner violence. J Marriage Fam 64(4):833–850

Browning CR, Cagney KA (2002) Neighborhood structural disadvantage, collective efficacy, and self-rated physical health in an urban setting. J Health Soc Behav 43(4):383–399

Browning CR, Feinberg SL, Deitz RD (2004) The paradox of social disorganization: networks, collective efficacy, and violent crime in urban neighborhoods. Soc Forces 83(2):503–534

Browning CR, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J (2005) Sexual initiation during early adolescence: the nexus of parental and community control. Am Sociol Rev 70(5):758–778

Bursik RJ (1988) Social disorganization and theories of crime and delinquency: problems and prospects. Criminology 26(4):519–552

Bursik RJ (1999) The informal control of crime through neighborhood networks. Sociol Focus 32(1):85–97

Bursik RJ, Grasmick HG (1993) Neighborhoods and crime: the dimensions of effective community control. Lexington Books, Maryland

Bushway S, Smith J (2007) Sentencing using statistical treatment rules: what we don’t know can hurt us. J Quant Criminol 23(4):377–387

Bushway S, Johnson BD, Slocum LA (2007) Is the magic still there? The use of the Heckman two-step correction for selection bias in criminology. J Quant Criminol 23(2):151–178

Carr PJ (2003) The new parochialism: the implications of the Beltway case for arguments concerning informal social control. Am J Sociol 108:149–1291

Chavis DM, Wandersman A (1990) Sense of community in the urban environment: a catalyst for participation and community development. Am J Community Psychol 18(1):55–81

Chwe MS (1999) Structure and strategy in collective action. Am J Sociol 105:128–156

Foster-Fishman PG, Cantillon D, Pierce SJ, Van Egeren LA (2007) Building an active citizenry: the role of neighborhood problems, readiness and capacity for change. Am J Community Psychol 24(1):5–32

Franzini L, Caughy M, Spears W, Esquer MEF (2005) Neighborhood economic conditions, social processes and self-rated health in low-income neighborhoods in Texas: a multilevel latent variables model. Soc Sci Med 61:1135–1150

Gau JM, Pratt TC (2008) Broken windows or window dressing? Citizens’ (in)ability to tell the difference between disorder and crime. Criminol Public Policy 7(2):163–194

Greenberg SW, Rohe WM (1986) Informal social control and crime prevention in modern urban neighborhoods. In: Taylor RB (ed) Urban neighborhoods: research and policy. Praeger Publishers, New York, pp 79–121

Greenberg SW, Rohe WM, Williams JR (1982) Informal citizen action and crime prevention at the neighborhood level. National Institute of Justice, Washington

Heckman JJ (1979) Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica 47:153–161

Horne C (2004) Collective benefits, exchange interests and norm enforcement. Soc Forces 82(3):1037–1062

Hunter AJ (1985) Private, parochial and public school orders: the problem of crime and incivility in urban communities. In: Suttles GD, Zald MN (eds) The challenge of social control: citizenship and institution building in modern society. Ablex Publishing, Norwood, pp 230–242

Kamata A, Bauer DJ (2008) A note on the relation between factor analytic and item response theory models. Struct Equ Modeling 15(1):136–153

Kennedy P (1998) A guide to econometrics. MA, MIT, Cambridge

Kerr NL (1983) Motivation losses in small groups: a social dilemma analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol 45:819–828

Kitts JA (1999) Not in our backyard: solidarity, social networks and the ecology of environmental mobilization. Sociol Inq 69(4):551–574

Kornhauser R (1978) Social sources of delinquency. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Kubrin CE (2008) Making order of disorder: a call for conceptual clarity. Criminol Public Policy 7(2):203–213

Macy MW (1991) Chains of cooperation: threshold effects in collective action. Am Sociol Rev 56:730–747

Maimon D, Browning CR, Brooks-Gunn J (2010) Collective efficacy, family attachment, and urban adolescent suicide attempts. J Health Soc Behav 51(3):307–324

Markowitz FE, Bellair PE, Liska AE, Liu J (2001) Extending social disorganization theory: modeling the relationships between cohesion, disorder and fear. Criminology 39(2):293–320

Marschall MJ (2004) Citizen participation and the neighborhood context: a new look at the coproduction of local public goods. Polit Res Q 57(2):231–244

Matsueda RL (2013) Rational choice research in criminology: a multi-level approach. In: Wittek R, Snijders T, Nee V (eds) Handbook of rational choice social research. Stanford University Press, Palo Alto, pp 283–321

Mazerolle LM, Wickes R, McBroom J (2010) Community variations in violence: the role of social ties and collective efficacy in comparative context. J Res Crime Delinq 47(1):3–30

Morenoff JD (2003) Neighborhood mechanisms and the spatial dynamics of birth weight. Am J Sociol 108:976–1017

Morenoff JD, Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW (2001) Neighborhood inequality, collective efficacy and the spatial dynamics of urban violence. Criminology 39(3):517–560

Neter J et al (1996) Applied linear statistical models. McGraw-Hill, Boston

Odgers CL, Moffitt T, Tach LM, Sampson RJ, Taylor A, Matthews CL, Capsi A (2009) The protective effects of neighborhood collective efficacy on British children growing up in deprivation: a developmental analysis. Dev Psychol 45(4):942–957

Ohmer ML (2007) Citizen participation in neighborhood organizations and its relationship to volunteers’ self and collective efficacy and sense of community. Soc Work Res 31(2):109–120

Oliver P (1984) If you don’t do it, nobody else will—active and token contributors to local collective action. Am Sociol Rev 49(5):601–610

Oliver P (1993) Formal models of collective action. Annu Rev Sociol 19:271–300

Olson M (1965) The logic of collective action. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Orbell J, Dawes R (1981) Social dilemmas. In: Stephenson G, Davis JH (eds) Progress in applied social psychology, vol 1. Wiley, Chichester

Otto G, Voss G, Willard L (2001) Common cycles across OECD countries. Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin, 6–11 Oct 2001

Pattillo ME (1998) Sweet mothers and gangbangers: managing crime in a black middle-class neighborhood. Soc Forces 76(3):747–774

Perkins DD, Florin P, Rich RC, Wandersman A, Chavis DM (1990) Participation and the social and physical environment of residential blocks: crime and community context. Am J Community Psychol 18(1):83–115

Raudenbush SW, Sampson RJ (1999) Ecometrics: toward a science of assessing ecological settings, with application to the systematic social observation of neighborhoods. Sociol Methodol 29:1–41

Reynald DE (2010) Guardians on guardianship: factors affecting the willingness to supervise, the ability to detect potential offenders and the willingness to intervene. J Res Crime Delinquency 47(3):358–390

Rhineberger-Dunn GM, Carlson SM (2009) Confirmatory factor analyses of collective efficacy and police satisfaction. J Crime Justice 32(1):125–154

Rohe WM, Stegman MA (1994) The impact of home ownership on the social and political involvement of low-income people. Urban Aff Rev 30(1):152–172

Rubin DB (1976) Inference and missing data. Biometrika 63:581–592

Sampson RJ (1988) Local friendship ties and community attachment in mass society: a multilevel systemic model. Am Sociol Rev 53(5):766–779

Sampson RJ (2001) Crime and public safety: insights from community-level perspectives on social capital. In: Saegert S, Thompson JP, Warren MR (eds) Social capital and poor communities. Russell Sage Foundation, New York, pp 89–114

Sampson RJ (2002) Transcending tradition: new directions in community research, Chicago style. Criminology 40(2):213–230

Sampson RJ (2006) Collective efficacy theory: lessons learned and directions for future inquiry. In: Cullen FT, Wright JP, Blevins KR (eds) Taking stock: the status of criminological theory (Advances in Criminological Theory Vol 15). Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick, pp 149–168

Sampson RJ (2012) Great American City: Chicago and the enduring neighborhood effects. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Sampson RJ (2013) The place of context: a theory and strategy for criminology’s hard problems. Criminology 51(1):1–31

Sampson RJ, Groves WB (1989) Community structure and crime: testing social-disorganization theory. Am J Sociol 94(4):774–802

Sampson RJ, Wikström PO (2008) The social order of violence in Chicago and Stockholm neighborhoods: a comparative inquiry. In: Shapiro I, Kalyvas SN, Masoud T (eds) Order, conflict, and violence. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 97–119

Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F (1997) Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 277:918–924

Sampson RJ, Morenoff J, Earls F (1999) Beyond social capital: spatial dynamics of collective efficacy for children. Am Sociol Rev 64:633–660

Shaw C, McKay H (1942) Juvenile delinquency and urban areas. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Silver E, Miller LL (2004) Sources of informal social control in Chicago neighborhoods. Criminology 42(3):551–583

Skogan W (1986) Fear of crime and neighborhood change. Crime Justice 8(1):203–229

Steenbeek W, Hipp JR (2011) A longitudinal test of social disorganization theory: Feedback effects among cohesion, social control and disorder. Criminology 49(3):833–871

Stern MJ, Fullerton AS (2009) The network structure of local and extra-local voluntary participation: the role of core social networks. Soc Sci Q 90(3):553–575

Swaroop S, Morenoff JD (2006) Building community: the neighborhood context of social organization. Soc Forces 84(3):1665–1695

Uchida CD, Swatt ML, Solomon SE, Varano S (2014) Neighborhoods and crime: collective efficacy and social cohesion in Miami-Dade County. Executive Summary, Final Report submitted to the National Institute of Justice

Warner BD (2007) Directly intervene or call the authorities? A study of forms of neighborhood social control within a social disorganization framework. Criminology 45(1):99–129

Warner BD (2014) Neighborhood factors related to the likelihood of successful informal social control efforts. J Crim Justice 42(5):421–430

Warner BD, Burchfield K (2011) Misperceived neighborhood values and informal social control. Justice Q 28(4):606–630

Warner BD, Wilcox Roundtree P (1997) Local social ties in a community and crime model: questioning the systemic nature of informal social control. Soc Probl 44(4):520–536

Weisburd DL, Groff ER, Yang SM (2012) The criminology of place: street segments and our understanding of the crime problem. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Weisburd DL, Groff ER, Yang SM (2014) The importance of both opportunity and social disorganization theory in a future research agenda to advance criminological theory and crime prevention at place. J Res Crime Delinquency 51(4):499–508

Wells W, Schafer JA, Varano SP, Bynum TS (2006) Neighborhood residents’ production of order: the effects of collective efficacy on responses to neighborhood problems. Crime Delinquency 52(4):523–550

Wickes R (2010) Generating action and responding to local issues: Collective efficacy in context. Aust N Z J Criminol 43(3):423–443

Wikström POH, Oberwittler D, Treiber K, Hardie B (2012) Breaking rules: the social and situational dynamics of young people’s urban crime. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Woldoff RA (2002) The effect of local stressors on neighborhood attachment. Soc Forces 81:87–116

Xiao C, McCright AM (2014) A test of the biographical availability argument for gender differences in environmental behaviors. Environ Behav 46(2):241–263

Zhang L, Messner SF, Liu J (2007) A multilevel analysis of the risk of household burglary in the city of Tianjin, China. Br J Criminol 47(6):918–937

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Australian Research Council (RO700002; DP1093960 and DP1094589). The authors would like to thank the Queensland Police Service (QPS) and the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence in Policing and Security (CEPS) for their support in the collection of these data. The authors would also like to thank the editor, reviewers, Barbara Warner, Lisa Broidy, Renee Zahnow and Michelle Sydes for their valuable feedback on this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wickes, R., Hipp, J., Sargeant, E. et al. Neighborhood Social Ties and Shared Expectations for Informal Social Control: Do They Influence Informal Social Control Actions?. J Quant Criminol 33, 101–129 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-016-9285-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-016-9285-x