Abstract

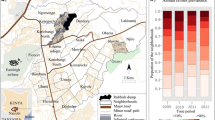

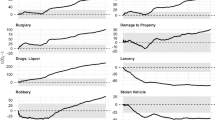

There is growing evidence that crime is strongly concentrated in micro-geographic hot spots, a fact that has led to the wide-scale use of hot spots policing programs. Such programs are ordinarily focused on deterrence due to police presence, or other law enforcement interventions at hot spots. However, preliminary basic research studies suggest that informal social controls may also be an important mechanism for crime reduction on high crime streets. Such research has been hindered by a lack of data on social and attitudinal characteristics of residents, and the fact that census information is not available at the micro-geographic level. Our study, conducted in Baltimore, MD, on a sample of 449 residential street segments, overcame these limitations by collecting an average of eight surveys (N = 3738), as well as physical observations, on segments studied. This unique primary data collection allowed us to develop the first direct indicators of collective efficacy at the micro-geographic level, as well as a wide array of indicators of other possible risk and protective factors for crime. Using multilevel negative binomial regression models, we also take into account community-level influences, and oversample crime hot spots to allow for robust comparisons across streets. Our study confirms the importance of opportunity features of streets such as population size and business activity in understanding crime, but also shows that informal social controls, as reflected by collective efficacy, are key for understanding crime on high crime streets. We argue that it is time for police, other city agencies, and NGOs to begin to work together to consider how informal social controls can be used to reduce crime at residential crime hot spots.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The initial threshold for violent and drug crime was 18 drug calls and 19 violence-related calls, respectively--approximately the top 2.5% of segments in the city for each category. We chose this threshold because it was about midway between the 1% and 5% thresholds that have often been used to define crime hot spots (e.g., see Weisburd 2015). Although, this was the final threshold for the combined violent and drug crime hot spots, to meet sampling goals for streets that were hot spots of violence or hot spots of drug crime the threshold was reduced to 17 violent calls and 16 drug crime calls respectively (approximately the top 3% of all city street segments in that category). We also required that streets evidence drug or violent crime throughout the year by setting a criterion that calls be spread across at least 6 months. For full details regarding the methodology of this study, see https://cebcp.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/NIDA-Methodology.pdf.

The survey instrument was adapted from different surveys used in the social sciences, particularly communities and crime research, as well as health surveys. Different surveys included the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods: Community Survey, the National Crime Victimization Survey, the RAND 36 Item Health Survey, the HCSIS Baseline Questionnaire, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, the National Youth Panel, among others. Question indexes were written based on prior research and scale development. Focus groups were used during the development of the survey, and the instrument was reviewed by experts, pilot tested in another city, and revisions made prior to the start of the survey in Baltimore.

With a street segment population of 25 households for example, the variance of the estimator is between 20 and 28% of the within-street segment variance of the variable in question at a sample size of between 10 and 7.

All street segments are included in the final analyses because there are no missing values for variables at the street segment level. It is also the case that there were very few missing values for measures from the survey that are aggregated up to develop street segment estimates. Except for income, which included 26% missing values, the maximum percentage for other measures utilized was below 3%. To create street level measures, we averaged individual responses.

This business activity measure was highly correlated (r = 0.7) with our measure of percent commercial buildings collected during the physical observations. Results do not change substantively when using either measure of business activity.

Because our street segments only represent 449 out of 25,045 streets in the city, Moran’s I was not an appropriate statistic for estimating the impacts of spatial auto correlation on our estimates. For example, using a 1/4 mile distance, a number of our streets do not have a neighbor in the data. We ran Spatial Lag and Spatial Error models in GeoDa for the one-level model with the dependent variable, 2017 crime incidents, logged, including the same level-1 independent variables as in our multi-level model, and the main findings are similar (output available by request). We report the negative binomial multilevel model because of the value added from the multilevel negative binomial modeling component.

The boundaries of 26 streets fell in more than one CSA. We used the approach of placing such streets in the CSA where the largest proportion of the street was found. To address whether the definition of CSA impacted our analyses, we also ran the regressions with these streets removed. We do not observe meaningful differences in these analyses as contrasted with those reported in the article.

While we cannot compute an ICC for this model (see Raudenbush and Bryk 2002), it is possible to calculate the ratio of the variability in the community-level means in the logged crime incident to the total variability in logged crime incidents. For our data, this value is 0.325, indicating that 32.5% of the variability in logged crime incidents is at the community-level.

In a paper published in the British Journal of Criminology, Weisburd, White and Wooditch (2020) examined the correlation of collective efficacy to citizen crime calls (as contrasted with crime incidents) close to the baseline year. That study did not control for baseline crime estimates or spatial lag effects, but suggested that citizen evaluations of crime and collective efficacy are strongly linked.

Our data provide strong support for this view in the relationship between social disorder and collective efficacy (r = − 0.55). The correlation is more modest for physical disorder (r = − 0.19).

We think this is an intriguing result which should be examined more carefully in future studies. The outcome we observe could result from positive prevention impacts of women on crime on high crime streets (Anderson 1999; St. Jean 2007), or the fact that women in the sample are less likely to employed and therefore more likely to be at home and act as guardians on the street (χ2 = 30.61; p < .001) (Cohen and Felson 1979).

References

Anderson, E. (1999). Code of the street: Decency, violence, and the moral life of inner city. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, Inc..

Andresen, M. A., & Malleson, N. (2011). Testing the stability of crime patterns: Implications for theory and policy. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 48, 58–82.

Apparicio, P., Abdelmajid, M., Riva, M., & Shearmur, R. (2008). Comparing alternative approaches to measuring the geographical accessibility of urban health services: Distance types and aggregation-error issues. International Journal of Health Geographics, 7(1), 7.

Armstrong, T. A., Katz, C. M., & Schnebly, S. M. (2015). The relationship between citizen perceptions of collective efficacy and neighborhood violent crime. Crime and Delinquency, 61(1), 121–142.

Babbie, E. (2007). The practice of social research (11th ed.). Belmont: Wadsworth.

Baumer, E. P., Lauritsen, J. L., Rosenfeld, R., & Wright, R. (1998). The influence of crack cocaine on robbery, burglary, and homicide rates: A cross-city, longitudinal analysis. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 35, 316–340.

Bellair, P. E. (1997). Social interaction and community crime: Examining the importance of neighbor networks. Criminology, 35, 677–704.

Bellair, P. E. (2000). Informal surveillance and street crime: A complex relationship. Criminology, 38, 137–170.

Braga, A. A., & Bond, B. J. (2008). Policing crime and disorder hot spots: A randomized controlled trial. Criminology, 46(3), 577–607.

Braga, A. A., & Clarke, R. V. (2014). Explaining high-risk concentrations of crime in the city: Social disorganization, crime opportunities, and important next steps. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 51, 480–498.

Braga, A. A., Papachristos, A. V., & Hureau, D. M. (2014). The effects of hot spots policing on crime: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Justice Quarterly, 31(4), 633–663.

Brantingham, P. L., & Brantingham, P. J. (1993). Environment, routine, and situation: Toward a pattern theory of crime. In R. V. Clarke & M. Felson (Eds.), Routine activity and rational choice. Crime prevention studies (Vol. 5, pp. 259–294). New Brunswick: Transaction.

Brantingham, P., & Brantingham, P. (1995). Criminality of place. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 3(3), 5–26.

Browning, C. R., Feinberg, S. L., & Dietz, R. D. (2004). The paradox of social organization: Networks, collective efficacy, and violent crime in urban neighborhoods. Social Forces, 83, 503–534.

Bursik Jr., R. J., & Webb, J. (1982). Community change and patterns of delinquency. American Journal of Sociology, 88(1), 24–42.

Bursik Jr., R. J. (1988). Social disorganization and theories of crime and delinquency: Problems and prospects. Criminology, 26, 519–551.

Chant, S. (2004). Dangerous equations? How female-headed households became the poorest of the poor: Causes, consequences and cautions. IDS Bulletin, 35(4), 19–26.

Clarke, R. V. (1995). Situational crime prevention. Crime and Justice, 19, 91–150.

Cohen, L. E., & Felson, M. (1979). Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review, 44, 558–608.

Dong, B., White, C., & Weisburd, D. (2020). Poor health and violent crime hot spots: Mitigating the undesirable co-occurrence through focused place-based interventions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2019.12.012.

Felson, M. (1986). Predicting crime potential at any point on the city map (pp. 127–136). Monsey: Metropolitan crime patterns. Criminal Justice Press.

Gomez, M. B. (2016). Policing, community fragmentation, and public health: Observations from Baltimore. Journal of Urban Health, 93, S154–S167.

Grannis, R. (1998). The importance of trivial streets: Residential streets and residential segregation. American Journal of Sociology, 103(6), 1530–1564.

Grannis, R. (2005). T-communities: Pedestrian street networks and residential segregation in Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York. City & Community, 4(3), 295–321.

Green Mazerolle, L., Ready, J., Terrill, W., & Waring, E. (2000). Problem-oriented policing in public housing: The Jersey City evaluation. Justice Quarterly, 17(1), 129–158.

Groff, E. R., & Lockwood, B. (2014). Criminogenic facilities and crime across street segments in Philadelphia: Uncovering evidence about the spatial extent of facility influence. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 51(3), 277–314.

Hipp, J. R., & Kim, Y.-A. (2019). Explaining the temporal and spatial dimensions of robbery: Differences across measures of the physical and social environment. Journal of Criminal Justice, 60, 1–12.

Holbrook, A., Krosnick, J., & Pfent, A. (2008). The causes and consequences of response rates in surveys by the news media and government contractor survey research firms. In J. M. Lepkowski, C. Tucker, J. M. Brick, E. D. Leeuw, L. Japec, P. J. Lavrakas, M. W. Link, & R. L. Sangster (Eds.), Advances in telephone survey methodology (pp. 499–528). New York: Wiley.

Irvin-Erickson, Y., & La Vigne, N. (2015). A spatio-temporal analysis of crime at Washington, DC metro rail: Stations’ crime-generating and crime-attracting characteristics as transportation nodes and places. Crime Science, 4(1), 14.

Jones, R. W., & Pridemore, W. A. (2019). Toward an integrated multilevel theory of crime at place: Routine activities, social disorganization, and the law of crime concentration. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 35(3), 543–572.

Kingston, B., Huizinga, D., & Elliott, D. S. (2009). A test of social disorganization theory in high-risk urban neighborhoods. Youth and Society, 41, 53–79.

Klinger, D. A., & Bridges, G. S. (1997). Measurement error in calls-for-service as an indicator of crime. Criminology, 35(4), 705–726.

Kornhauser, R. (1978). Social sources of delinquency. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Krivo, L. J., & Peterson, R. D. (1996). Extremely disadvantaged neighborhoods and urban crime. Social Forces, 75, 619–650.

Levas, M., & Nimmer, M. (2017). An independent evaluation of Safe & Sound’d community building strategies. Safe & Sound. Retrieved from: https://safesound.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Evaluation-Report_gen-use.pdf.

Loukaitou-Sideris, A. (1999). Hot spots of bus stop crime: The importance of environmental attributes. Journal of the American Planning Association, 65(4), 395–411.

Mazerolle, L., Wickes, R., & McBroom, J. (2010). Community variations in violence: The role of social ties and collective efficacy in comparative context. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 47(1), 3–30.

McCord, E. S., & Ratcliffe, J. H. (2009). Intensity value analysis and the criminogenic effects of land use features on local crime patterns. Crime Patterns and Analysis, 2(1), 17–30.

Merse, C. L., Buckley, G. L., & Boone, C. G. (2008). Street trees and urban renewal: A Baltimore case study. The Geographical Bulletin, 50, 65–81.

Morenoff, J. D., Sampson, R. J., & Raudenbush, S. W. (2001). Neighborhood inequality, collective efficacy, and the spatial dynamics of urban violence. Criminology, 39(3), 517–558.

Nagin, D. S., Solow, R. M., & Lum, C. (2015). Deterrence, criminal opportunities, and police. Criminology, 53(1), 74–100.

Parker, K. F., & Reckdenwald, A. (2008). Concentrated disadvantage, traditional male role models, and African-American juvenile violence. Criminology, 46(3), 711–735.

Perkins, D. D., Florin, P., Rich, R. C., Wandersman, A., & Chavis, D. M. (1990). Participation and the social and physical environment of residential blocks: Crime and community context. American Journal of Community Psychology, 18, 83–115.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication Inc.

Rhew, I. C., Hawkins, J. D., Murray, D. M., Fagan, A. A., Oesterle, S., Abbott, R. D., & Catalano, R. F. (2016). Evaluation of community-level effects of communities that care on adolescent drug use and delinquency using a repeated cross-sectional design. Prevention Science, 17(2), 177–187.

Roman, C. G., Reid, S. E., Bhati, A. S., & Tereshchenko, B. (2008). Alcohol outlets as attractors of violence and disorder: A closer look at the neighborhood environment. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Sampson, R. J. (1988). Local friendships ties and community attachment in mass society: A multilevel systemic model. American Sociological Review, 53, 766–779.

Sampson, R. J. (2006). Collective efficacy theory: Lessons learned and directions for future inquiry. In F. T. Cullen, J. P. Wright, & K. R. Blevins (Eds.), Taking stock: The status of criminological theory. Advances in criminological theory (Vol. 15, pp. 149–167). New Brunswick: Transaction.

Sampson, R. J. (2012). Great American City: Chicago and the enduring neighborhood effect. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sampson, R. J., & Groves, W. B. (1989). Community structure and crime: Testing social-disoranization theory. The American Journal of Sociology, 94, 774–802.

Sampson, R. J., & Lauritsen, J. L. (1993). Violent victimization and offending: Individual-, situational-, and community-level risk factors. In A. J. Reiss Jr. & J. A. Roth (Eds.), Understanding and preventing violence, Panel on the understanding and control of violent behavior (Vol. 3, pp. 1–114). Washington: National Academy Press.

Sampson, R. J., & Raudenbush, S. W. (1999). Systematic observation of public spaces: A new look at disorder in urban neighborhoods. The American Journal of Sociology, 105, 603–651.

Sampson, R. J., Raudenbush, S. W., & Earls, F. (1997). Neighborhood and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science, 277, 918–924.

Sampson, R. J., Morenoff, J. D., & Earls, F. (1999). Beyond social capital: Spatial dynamics of collective efficacy for children. American Sociological Review, 64, 633–660.

Shaw, C. R., & McKay, H. D. (1942). Juvenile delinquency and urban areas. In A study of rates of delinquency in relation to differential characteristics of local communities in American cities. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sherman, L. W., & Weisburd, D. (1995). General deterrent effects of police patrol in crime “hot spots”: A randomized, controlled trial. Justice Quarterly, 12, 625–648.

Sherman, L. W., Gartin, P. R., & Buerger, M. E. (1989). Hot spots of predatory crime: Routine activities and the criminology of place. Criminology, 27, 27–56.

Spoth, R., & Greenberg, M. (2011). Impact challenges in community science-with-practice: Lessons from PROSPER on transformative practitioner-scientist partnerships and prevention infrastructure development. American Journal of Community Psychology, 48(1–2), 106–119.

Spoth, R., Greenberg, M., Bierman, K., & Redmond, C. (2004). PROSPER community-university partnership model for public education systems: Capacity-building for evidence-based, competence-building prevention. Prevention Science, 5(1), 31–39.

St. Jean, P. K. B. (2007). Pockets of crime: Broken windows, collective efficacy, and the criminal point of view. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Telep, C. W., & Weisburd, D. (2018). Crime concentrations at places. In G. J. N. Bruinsma & S. D. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Environmental Criminology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Thrasher, F. M. (1927 [1963]). The gang: A study of 1,313 gangs in Chicago. Chicago: Phoenix.

Velez, M. B. (2001). The role of public social control in urban neighborhoods: A multi-level analysis of victimization risk. Criminology, 39, 837–864.

Weisburd, D. (2015). The law of crime concentration and the criminology of place. Criminology, 53(2), 133–157.

Weisburd, D., & Majmundar, M. K. (2018). Proactive policing: Effects on crime and communities. Washington: National Academies Press .

Weisburd, D., Wyckoff, L., Ready, J., Eck, J. E., Hinkle, J., & Gajewski, F. (2006). Does crime just move around the corner? A controlled study of spatial displacement and diffusion of crime control benefits. Criminology, 44, 549–592.

Weisburd, D., Lawton, B., Ready, J., & Haviland, A. (2011). Longitudinal study of community health and anti-social behavior at drug hot spots. National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health. [Grant no. 5R01DA032639–03, 2012].

Weisburd, D., Groff, E. R., & Yang, S. M. (2012). The criminology of place: Street segments and our understanding of the crime problem. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Weisburd, D., Groff, E. R., & Yang, S. M. (2014). Understanding and controlling hot spots of crime: The importance of formal and informal social controls. Prevention Science, 15(1), 31–43.

Weisburd, D. L., Cave, B., Nelson, M., White, C., Haviland, A., Ready, J., et al. (2018). Mean streets and mental health: Depression and post-traumatic stress disorder at crime hot spots. American Journal of Community Psychology, 61, 285–295.

Weisburd, D., Gill, C., Wooditch, A., Barritt, W., & Murphy, J. (2020a). Building collective action at crime hot spots: Findings from a randomized field experiment. Journal of Experimental Criminology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-019-09401-1.

Weisburd, D., White, C., & Wooditch, A. (2020b). Does collective efficacy matter at the micro geographic level?: Findings from a study of street segments. British Journal of Criminology, 60(4), 873–891.

White, C., & Weisburd, D. (2018). A co-responder model for policing mental health problems at crime hot spots: Findings from a pilot project. Policing: a journal of policy and practice, 12(2), 194–209.

Wicker, A. W. (1987). Behavior settings reconsidered: Temporal stages, resources, internal dynamics, context. In D. Stokols & I. Altman (Eds.), Handbook of environmental psychology (pp. 613–653). New York: Wiley.

Wikström, P. O. H., Oberwittler, D., Treiber, K., & Hardie, B. (2012). Breaking rules: The social and situational dynamics of young people's urban crime. Oxford: OUP.

Wilcox, P., & Tillyer, M. S. (2018). Place and neighborhood contexts. In D. Weisburd & J. E. Eck (Eds.), Unraveling the crime-place connection. New York: Routledge.

Wilcox, P., Land, K. C., & Hunt, S. C. (2003). Criminal circumstance: A dynamic multicontextual criminal opportunity theory. New York: Walter de Gruyster.

Wilcox, P., Madensen, T. D., & Tillyer, M. S. (2007). Guardianship in context: Implications for burglary victimization risk and prevention. Criminology, 45(4), 771–803.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant number 5R01DA032639-03, 2012].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of George Mason University. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 34 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Weisburd, D., White, C., Wire, S. et al. Enhancing Informal Social Controls to Reduce Crime: Evidence from a Study of Crime Hot Spots. Prev Sci 22, 509–522 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-020-01194-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-020-01194-4