Abstract

We document the historical roots and contemporary consequences of masculinity norms—beliefs about the proper conduct of men. We exploit a natural experiment in which convict transportation in the \(18^{\textrm{th}}\) and \(19^{\textrm{th}}\) centuries created a variegated spatial pattern of sex ratios across Australia. We show that in areas with heavily male-biased convict populations, relatively more men volunteered for World War I about a century later. Even at present these areas remain characterized by more violence, higher rates of male suicide and other forms of preventable male mortality, and more male-stereotypical occupational segregation. Moreover, in these historically male-biased areas, more Australians recently voted against same-sex marriage and boys—but not girls—are more likely to be bullied in school. We interpret these results as manifestations of masculinity norms that emerged due to intense local male-male competition. Once established, masculinity norms persisted over time through family socialization as well as peer socialization in schools.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

What makes a ‘real’ man? A particular normative form of masculinity, often described as hegemonic, posits that men ought to be self-reliant, assertive, competitive, dominant, violent when needed, and in control of their emotions (Mahalik et al., 2003; Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005). Three current debates illustrate how such masculinity norms can have profound economic and social impacts. A first debate concerns the fact that in many countries men die younger than women, and are consistently less healthy (Case & Paxson, 2005; IHME, 2010; Baker et al., 2014). Masculinity norms—especially a penchant for violence and risk taking—are an important cultural driver of this gender health gap (WHO, 2013; Schanzenbach et al., 2016).

A second debate links masculinity norms to occupational gender segregation. Technological progress and globalization have disproportionately affected male employment (Autor et al., 2019). Many newly unemployed men nevertheless refuse to fill jobs that do not match their self-perceived gender identity (Akerlof & Kranton, 2000, 2010) and choose instead to remain unemployed or leave the labor force (Katz, 2014). Restrictive masculinity norms then impose constraints on occupational choice that may be economically inefficient if they increase search costs, misallocate talent, and lead to sectoral staff shortages. Economic growth may suffer as a result.

Third, masculinity norms have become integral to debates about the socio-economic inclusion of women and sexual minorities in Western society. These cultural changes can threaten the identity of men who adhere to conservative masculinity norms, provoking a backlash against women and minorities (Kimmel, 2013; Horvilleur, 2019; Inglehart & Norris, 2019).

While there are striking similarities across countries regarding the ideals that men are expected to adhere to (Gilmore, 1990), the extent to which men have to conform to such norms differs across societies (Traister, 2000). This raises the question: Where do masculinity norms come from? The origins of gender norms that guide and constrain the behavior of women have been the focus of an important recent literature (Fernández et al., 2004; Alesina et al., 2013; Carranza, 2014; Giuliano, 2018; Grosjean & Khattar, 2019; Galor et al., 2020). Our focus is, instead, on the origins and manifestations of norms that guide and constrain the behavior of men.

Our contribution is to show how masculinity norms can be shaped by historical circumstances that skew sex ratios, thus creating a shortage of women and heightening competition among men. Intense male-male competition not only establishes a dominance order (that is, it determines males’ relative access to resources and mates) but also gives rise to a set of behavorial norms.

To establish a causal link from sex ratios to the manifestation of masculinity norms, we exploit a natural experiment—the convict colonization of Australia. Between 1787 and 1868, Britain transported 132,308 convict men but only 24,960 convict women to Australia. This imposed a variegated spatial pattern in sex ratios, which led to local variation in male-to-male competition in an otherwise homogeneous setting. We test this idea by combining information on historical sex ratios among convicts, using data from Australian colonial censuses compiled by Grosjean and Khattar (2019) [henceforth GK], with proxies for intermediary and present-day masculinity norms. These include voluntary recruitment during WWI, violent behavior and crime, suicide, bullying, help-avoiding behavior, COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, and stereotypically male occupational choice. Moreover, we capture the political expression of masculine identity by opposition against same-sex marriage, which we measure using voting records from a unique nation-wide referendum on same-sex marriage in 2017.

We focus on these outcomes as they are well-accepted behavioral manifestations of hegemonic masculinity norms in Western societies.Footnote 1 Mahalik et al. (2003) develop an inventory of 11 core masculinity norms: winning; emotional control; risk-taking; violence; dominance; playboy; self-reliance; primacy of work; power over women; disdain for homosexuals; and pursuit of status.Footnote 2 Among these, we focus on those norms that are likely to generate behaviors that are observationally distinct from behaviors that are influenced by male–female bargaining. After all, certain behaviors classified as manifestations of masculinity norms, such as the primacy of work, pursuit of status, or power over women, may also be influenced by male–female bargaining (with male-biased sex ratios granting a more favorable bargaining position to women). This may make it difficult to single out masculinity norms as a separate channel.

For this reason, this paper studies behavioral manifestations of masculinity norms for which the conditions of male–female bargaining should either have no influence or select for opposite behaviors. The most prominent example is male violence. Men who are behaviorally aggressive towards other men in competitive contexts may also be prone to aggression in the context of marriage or other long-term relationships. They may also be prone to sexual coercion.Footnote 3 Studies show that women have a distaste for violent men and turn away from men whose traits signal aggressive potential (Li et al., 2014). More generally, women tend to prefer cooperative men (Phillips et al., 2008).

Other behavioral manifestations of masculinity norms that we study in this paper—such as help-avoiding behavior (and associated premature death), male suicide, and voluntary participation in WWI—negatively affect women as wives, especially in an environment where men are economic providers. These behaviors, as well as the bullying of boys in schools and low tolerance of same-sex relationships, also hurt mothers (possibly more than fathers, to the extent that women care more for their children’s welfareFootnote 4). We check that the proxies for masculinity norms that we use in this paper are uncorrelated with gender norms about the social and economic role of women.

Our results paint a consistent picture of how skewed sex ratios instilled masculinity norms that deeply influence the social and economic landscape to this day. By way of preview, we find that a one standard deviation increase in the sex ratio among convicts is associated with a 5.6% increase in the share of men who served in WWI, with no effect on female volunteers. Areas that were more male-biased in the past (though not the present) remain characterized by more assaults (+ 8.8%), sexual assaults (+ 12.8%), male suicide rates (+ 20.2%), prostate cancer (+ 3.3%), and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among men (+18.2 percent). A one standard deviation increase in the convict sex ratio is also associated with a 0.7% point shift in the share of men employed in feminine or neutral occupations towards stereotypically male occupations.

Moreover, we find that in areas that were heavily male-biased, fewer Australians support same-sex marriage today, and boys are more likely to fall victim to bullying in school. A one standard deviation increase in the convict sex ratio is associated with a 2.2% point decrease in the probability of voting "Yes" to same-sex marriage and a 3.6–8.5% point increase in the bullying of boys in schools, depending on whether we base our estimates on reports by teachers or parents. We take this last result as evidence of peer socialization and the transmission of masculinity norms, which helps to explain the persistent effects of historical sex ratios. Importantly, we see no variation in the rates of non-violent crime, in political opinions unrelated to the status of sexual minorities, in female suicide, female COVID vaccine hesitancy, or in the bullying of girls.

We interpret these strong local impacts of historical sex ratios on intermediary and present-day outcomes for men as manifestations of hegemonic masculinity norms. We back up this interpretation by bringing additional survey data to bear that reveal a tight relationship between actual measurements of Australian men’s conformity to masculinity norms and outcomes such as suicide attempts; violent behavior; and health care avoidance.

The main empirical challenge in estimating the impact of sex ratios on manifestations of masculinity norms is that variation in sex ratios usually reflects characteristics that arise from spatial selection. Men and women sort across geographic areas based on observable or unobservable characteristics that are possibly related to outcomes of interest. For example, fewer women may choose to live in areas where men are more violent. In turn, such characteristics may persist over time and induce a spurious correlation between historical sex ratios and the type of present-day outcomes that are attributable to masculinity norms. We avoid this confound by focusing on historical sex ratios among convicts. Convicts were not free to move: a centralized assignment scheme determined their location as a function of labor needs to develop the country, which we proxy by initial economic specialization. This circumvents the possibility that our results are driven by self-selection across different areas of Australia.

Throughout, our estimates include state fixed effects to account for the influence of time-invariant state characteristics such as legislation or differences in patterns of settlement across states. In addition, we check that convict sex ratios do not systematically vary as a function of environmental or economic characteristics and are uncorrelated with industrial specialization. Even then, our results are robust to controlling for such initial circumstances, including mineral or land endowments and economic specialization. Our results also hold in a wide range of robustness tests—such as including additional contemporaneous controls like the present-day sex ratio, urbanization, share of various religious groups, and unemployment. Oster (2019) bounds confirm that our estimated coefficients are relatively stable, thus alleviating concerns about omitted variables basis. Moran statistics show that our findings do not merely reflect spatial autocorrelation of the error terms.

A concern is that convicts were different from the rest of the population in ways that are correlated with our outcomes of interest. In particular, convicts may have been more prone to violence, crime, and risk taking and it could be the persistence of this convict ‘stain’ that we observe today.Footnote 5 Historical evidence argues against such a mechanism. As we describe in the historical background section, convicts transported to Australia were not “hardened and professional criminals" (Nicholas, 1988, p. 3) but rather “ordinary working-class men and women" (Nicholas, 1988, p. 7). The majority was transported for a first offense, usually a minor property offense such as petty theft (Oxley, 1996). Nevertheless, we control for the number of convicts, together with total population, throughout.

Our results contribute to several strands of the literature. First and foremost, we provide a new perspective on the causes, nature, and consequences of gender norms (Giuliano, 2018).Footnote 6 Recent work explores the historical origins of norms about women, including differences in technology (Alesina et al., 2013; Xue, 2016), soil structure (Carranza, 2014), political institutions (Lippmann et al., 2016) or sex ratios (Gay 2021, GK, Teso, 2019, Caicedo et al., 2020). Related work assesses the impact of the resulting female identity on household formation and female work choices (Bertrand et al., 2015).

The previous economic literature on the effects of sex ratios has focused on male–female bargaining. In line with models of the marriage market (Becker, 1973, 1974), studies have shown how a relative scarcity of women influences how men and women interact within the household (Heer & Grossbard, 1981; Grossbard-Shechtman, 1984; Chiappori et al., 2002; Grossbard & Amuedo-Dorantes, 2008; Grossbard, 2015). Over time these interactions shape social norms about female work (Gay, 2021; Grosjean & Khattar, 2019). Instead, we focus on a different, and novel, mechanism: how a scarcity of women determines how men interact and compete with one other and thus shape behavioral norms for men.Footnote 7

We document how such masculinity norms continue to manifest themselves in various ways, such as men shunning stereotypically female occupations, engaging in violence, and opposing same-sex marriage. We put forward intrasexual competition as a theoretical framework to understand the contemporaneous relationships between skewed sex ratios and violent crime (Hesketh & Xing, 2006; Edlund et al., 2013; Cameron et al., 2019), molestation and rape (Ullman & Fidell, 1989), as well as suicide and early mortality (Chowdhry, 2005; Chang et al., 2021), which have been documented in other contexts.Footnote 8 Our results suggest that these relationships may be longer lasting than previously thought if these behaviors become entrenched norms.Footnote 9

We also contribute to an emerging literature on the economic role of norms and identity (Akerlof & Kranton, 2000, 2010; Bénabou & Tirole, 2011; Gennaioli & Tabellini, 2019) as well as stereotypes (Bordalo et al., 2016). Several studies highlight the role of perceived threats to one’s honor or reputation (Nisbett & Cohen, 1996; Cohen et al., 1996; Grosjean, 2014; Cao et al., 2021) or one’s masculinity (Wilson & Daly, 1985) as drivers of violence. We suggest that concerns about status or male identity are heightened in more competitive environments and can have long-lasting effects on violent tendencies towards others but also oneself (suicide).

Relatedly, conforming to hegemonic masculinity norms has been hypothesized to constitute an important cause of stubborn male unemployment despite the availability of (stereotypically female) service jobs (Akerlof & Kranton, 2010; Katz, 2014), thereby potentially lowering economic growth. We provide empirical evidence that masculinity norms can indeed manifest themselves in the labor market through male-stereotypical occupational segregation.

Lastly, we contribute to the literature on the determinants of support for minorities’ civil rights, such as same-sex relationship recognition. Most studies focus on individual correlates of attitudes towards sexual minorities, highlighting the role of gender (Kite, 1984); education and rurality (Stephan & McMullin, 1982; Lottes & Kuriloff, 1994; Herek & Capitanio, 1996); or age and religion (Inglehart, 1990; Edwards, 2007).Footnote 10 A recent paper by Fernández et al. (2021) explores how (media coverage of) political discussions about the ban on gay people in the U.S. military changed attitudes towards same-sex relationships. Our contribution is to uncover historical roots of attitudes towards homosexuality and to suggest masculinity norms as a mechanism through which such attitudes become entrenched. Related to our work, Brodeur and Haddad (2021) find that same-sex relationships are more prevalent in places in the U.S. that experienced a Gold Rush. Their hypothesized mechanism consists of the self-selection of gay men to Gold Rush places, while our setting, based on the quasi-random allocation of British convicts, rules out initial self-selective migration on the basis of sexual preferences. A unique feature of our study is also that the Australian referendum provides unbiased and high-quality data on citizens’ revealed preferences for civil rights for sexual minorities. Given that real legislation was at stake, and turnout was high (at 79.5%), these data arguably better reflect people’s convictions than surveys that have so far been used to elicit attitudes towards sexual minorities.

We proceed as follows. Section 2 describes the conceptual background after which Sect. 3 provides some historical detail about colonial Australia. Section 4 describes the various data. Sections 5 and 6 then discuss our empirical approach and results. Section 7 considers mechanisms and Sect. 8 concludes.

2 Conceptual background

This section provides a conceptual discussion of the link between sex ratios and male-male competition (Sect. 2.1) and of the impact of sex ratios on masculinity norms and related outcomes (Sect. 2.2).

2.1 Sex ratios, male-male competition, and male–female bargaining

The sex ratio, the number of males relative to females, is a central concept in evolutionary biology. The idea that behavioral differences between the sexes originate in the conditions of reproductive competition, among which the sex ratio plays a primordial role, is the cornerstone of Darwin’s The Descent of Man (1871). When the sex ratio is more male biased, competition between males is more intense. Across a wide range of taxa, strong male-male competition induces risk taking, violence and control, oftentimes exerted through violent means, over the reproductive opportunities of dominated males as well as females (Emlen & Oring, 1977; Buss, 2016). Experimental studies of lizards, birds, and primates find that male-biased sex ratios increase male aggression towards males as well as females (Sapolsky, 1990, 1991). In human populations, skewed sex ratios have likewise been shown to correlate with rape and other violent crime.Footnote 11

Among humans, the behavioral consequences of male-biased sex ratios have so far been mostly analyzed through the lens of male–female bargaining, i.e. inter-sexual competition, within the framework of the Beckerian household model. Several contributions have studied how male-biased sex ratios increase female bargaining power and consequently shift resources and family structures. Women are then less likely to participate in the labor force (Grossbard-Shechtman, 1984; Chiappori et al., 2002; Grossbard & Amuedo-Dorantes, 2008; Grossbard, 2015), also work less within the home, and enjoy more leisure as a result (Grosjean & Khattar, 2019). Men, in contrast, work and save more to become attractive partners (Wei & Zhang, 2011) and adopt behavior and mating strategies more favorable to females’ interests (Guttentag & Secord, 1983; Pedersen, 1991). In particular, male-biased sex ratios correlate with more monogamy, more committed relationships and higher marriage rates (Grosjean & Khattar, 2019; Schacht & Kramer, 2016), greater marital stability and satisfaction (Otterbein, 1965; Grosjean & Brooks, 2017), and more paternal involvement (Schmitt, 2005).Footnote 12

To sum up, the literature contrasts the effects of sex ratios on aggression and violence in domains of intra-sexual competition—which have been documented across multiple animal taxa and are the focus of a large evolutionary biology literature—with their effects on inter-sexual cooperation, which has been the primary focus in economics. Alger (2021) develops a theoretical model that brings both elements together by conceptualizing male-male competition and male–female household formation as sequential matching evolutionary game. The strategies in the initial competition stage are the degrees of competitiveness. At stake are women (reproductive resources) and productive (material) resources that enable a man to provide parental care. An implication of this model is that male-biased sex ratios increase male-male competition in the short-run—if there are fewer women than men, not competing is not evolutionary stable—as well as in the long-run, since the degree of competitiveness is transmitted from fathers to sons. Another insight is that the outcome of the male-male competition stage is a fait accompli at the stage of female choice, and hence of male–female household bargaining later on. This is because, when faced with the order established by competition, a female’s reproductive success will be higher if she accepts the winner of the competition, who brings in additional resources.

In this paper, we ask what predictions can be made with respect to the influence of sex ratios on human behavior that operate through the mechanism of male-male competition. To do so, we focus on norms and behavioral outcomes for which male-male competition leads to predictions that are unrelated or opposite to the expected effects of male–female bargaining.

2.2 Skewed sex ratios, masculinity norms, and behavioral outcomes: Hypotheses

Because male-biased sex ratios heighten intra-sexual competition among men, we focus on male behaviors and the norms that regulate them: masculinity norms. These norms can be defined as the culturally accepted rules and standards that guide and constrain men’s behavior within society. To measure how much men adhere to such norms, Mahalik et al. (2003) developed the Conformity to Masculinity Norms Inventory (CMNI).

The CMNI is a multi-dimensional scale that measures to what extent an individual man’s actions, thoughts, and feelings conform to the dominant masculinity norms in Western societies. It captures 11 distinct masculinity norms: winning; emotional control; risk-taking; violence; dominance; playboy; self-reliance; primacy of work; power over women; disdain for homosexuals; and pursuit of status. We hypothesize that skewed sex ratios can influence masculinity norms that, once ingrained in local culture, continue to manifest themselves in present-day behaviors.Footnote 13 Such cultural persistence can be explained by both hysteresis due to parental transmission (Bisin & Verdier, 2001) and by conformity and peer effects (Acemoglu & Jackson, 2017; Ushchev & Zenou, 2020).

Based on the CMNI framework, we expect that areas that were historically characterized by male-biased sex ratios and, therefore, intense male-male competition, developed stricter masculinity norms that continue to manifest themselves across four broad domains: (i) violence and bullying; (ii) risk taking, help avoidance and unhealthy behavior; (iii) male-stereotypical occupational segregation; and (iv) negative attitudes towards homosexuals.

The underlying mechanism of interest is the intensification of male-male competition generated by male-biased sex ratios. As explained in the Introduction, we therefore focus on behaviors for which inter-sexual cooperation would predict behaviors that are either opposite or unrelated to the ones generated by intra-sexual competition, such as cooperation versus violence. We now explain in more detail how sex ratios likely influence behaviors in our four domains of interest.

First, in line with an effect of skewed sex ratios on violence and aggression, studies have documented that unmarried men—those exposed to intense competition for access to females—are more likely to commit crimes, including rape, murder, and assault (Sampson et al., 2006; Henrich et al., 2012). Accordingly, we examine outcomes such as violent assault, sexual offenses, as well as bullying in schools. Bullying in schools should also be understood as capturing the socialization process through which masculinity norms are imposed and transmitted to younger generations. Peers at school are a major influence on the development of gender normative behavior in childhood and adolescence (Adler et al., 1992; Leaper & Farkas, 2014).

Second, intense male-male competition is expected to favor risk taking, self-reliance and help avoidance, which may lead to increased morbidity and earlier death. As a proxy for risk taking, and a measure of intermediary outcomes that helps to ‘decompress history’, we use voluntary recruitment in WWI. Appeals to masculinity, including by public shaming of men not wearing uniforms as cowards, were a key driver of volunteering in WWI, especially in Australia where all recruits were volunteers (Becker, 2021; Inwood et al., 2020).

Men adhering to hegemonic masculinity norms attach a stronger stigma to mental health problems, are more likely to avoid health services (Good et al., 1989; Latalova et al., 2014) and are more likely to think about suicide (Pirkis et al., 2017). As a proxy for the avoidance of preventative health care we use answers to a survey question we commissioned about help-seeking behavior, a survey question about prostate cancer screening, as well as as deaths by suicide and prostate cancer rates. Prostate cancer is often curable if treated early, but avoidance of diagnosis and treatment is a major public health concern. A large medical literature has established a clear relationship between adherence to a masculine identity and the avoidance of prostate cancer screening.Footnote 14

A third manifestation of male identity for which we test, is occupational choice. The role of identity in determining job choice has been discussed since Akerlof and Kranton (2000). More recently, the role of masculine identity in preventing men from taking up occupations that are perceived as stereotypically female has attracted attention as a driver of so-called retrospective wait unemployment (Katz, 2014) and of occupational sorting between stereotypically male and female jobs (that is, occupational gender segregation). Milner et al. (2018) show for Australia that men in male-dominated jobs report greater adherence to masculine norms.

Fourth, the effect of higher historical sex ratios (and male-male competition) on attitudes towards homosexuality is a priori ambiguous. Male homosexuality should, at first sight, be welcomed, as it reduces the number of male competitors for scarce women. However, as explained above, the primary effect of a male-biased sex ratio is to intensify male-male competition. In their strife for dominance, men will aim to (often publicly) subdue other men, in particular those who do not display strong markers of masculinity and are perceived as easier targets, thereby encouraging bullying and aggression towards males perceived as not masculine enough (Franklin, 2000; Parrott & Zeichner, 2008; Vincent et al., 2011).

Men display sexual prejudice both to establish and reaffirm their own masculinity and to punish other men who fail to meet gender role requirements (Herek & McLemore, 2013). Indeed, the dread of being perceived as gay and the primacy of being thought to be heterosexual are among the strongest components of the CMNI scale, and correlate positively and significantly with other dimensions of masculinity, such as dominance, risk-taking, an inclination for violence, and negatively with emotional openness and help-seeking behavior. We will proxy this masculinity norm by opposition against same-sex marriage, which we measure using voting records from the 2017 nation-wide referendum on same-sex marriage and the results of a large-scale household survey.Footnote 15

To sum up, we expect that historically male-biased sex ratios led to heightened norms of masculinity as expressed in violent behavior and bullying; help avoidance and unhealthy behavior; occupational gender segregation; and less support for same-sex marriage.

3 Historical background

3.1 The arrival and allocation of convicts

Between 1787 and 1868, 132,308 male and 24,960 female convicts were transported from Britain to Australia. The 1836 and 1842 censuses in New South Wales and Tasmania showed that the average convict sex ratio stood at more than 28 men for every woman (Table 1). These convicts, who constituted the founder settler population of Australia, were far from being hardened criminals guilty of violent crime. Instead, they were quite representative of the Victorian working class at the time in terms of, for example, their occupations, literacy, numeracy, and height (Nicholas, 1988; Oxley, 1996; Meinzer, 2015). Based on evidence on violence-related injuries such as fractures, scars, and cuts, Meinzer (2015) concludes that convicts were not especially prone to violence as compared with the general population in Great Britain. Indeed, two thirds of transported convicts were first offenders of minor property crime, such as petty theft (Nicholas, 1988).Footnote 16

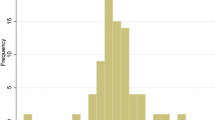

Once in Australia, convicts were not confined to prisons but were assigned to work, first under government supervision and later, as the number of free settlers and emancipists (ex-convicts) grew, under the direction of private employers. They were generally freed after the term of their sentence, usually seven years. Convicts made up as much as 38% of the population in the colonial Censuses of New South Wales and Tasmania that we use in this study.Footnote 17 Voluntary migration was very limited and mainly involved men migrating in response to male-biased economic opportunities available in agriculture and, after the discovery of gold in the 1850s, mining. Because of the predominance of male convicts and migrants, male-biased population sex ratios endured in Australia for more than a century, although less severely after the end of convict transportation (Fig. 1).

Using the sex ratio among convicts alleviates the self-selection issue that free men and women chose their location based on unobservable preferences. Convicts were not free to choose where to live but were allocated centrally on the basis of local labor needs. As part of our identification strategy, which we describe in more detail in Sect. 5, we therefore condition on a comprehensive set of proxies for local economic opportunities at the time. Identification then rests on the assumption that the spatial distribution of the relative number of convict men and women was as good as random once we control for historical employment sector shares and for geographic factors, including the location of minerals and land type.

Historical and cliometric evidence supports the idea that convicts were assigned on the basis of local labor requirements, which we can control for. One might worry that local convict populations differed not only in terms of their sex ratio but also in terms of other characteristics that may transmit across generations. For example, especially violent men may have been sent to (remote) areas with more male-biased sex ratios. Our results might then not only reflect the lasting impact of skewed sex ratios per se but also spatial variation in violent tendencies among men (which may have transmitted genetically or behaviorally over time).

There exists, however, little to no historical evidence supporting such an interpretation. Meredith (1988) describes how convicts were assigned according to their abilities and not ‘with reference to their sentence, crime or general ‘character”. As described by Governor Bligh of New South Wales in 1812: “They (the convicts) were arranged in our book for the purpose of distinguishing their ages, trades, and qualifications and whether sickly, or not, in order to enable me to distribute them according” (Meredith, 1988, p. 15, emphasis added). The treatment and assignment of a convict ‘bore no relation to his crime, general character and behavior or the length of his sentence’ (ibid, p. 19). According to Bligh: ‘If one person convicted of a great offense, and another of an inferior one, come out together, the Governor, having no such information, is not enabled to distribute them in reference to that circumstance; upon their arrival in the settlement they are all treated alike’ (ibid, p. 19). A convict’s previous crime and character were ‘points that are altogether overlooked’ and spatial allocation happened ‘not upon any retrospect of their former lives, or characters, or the length of their sentencing’. The Select Committee on Transportation concluded in 1837 that ‘Therefore on the whole, it must be a mere lottery with regard to the condition of the convict’ (Meredith, 1988, p. 20).

3.2 Masculinity norms in Australia: historical context

As a nation of convicts transported from Great Britain, perceptions of manhood in colonial Australia initially developed from those prevalent in Britain at the time. Tosh (2005) describes how this masculine identity was shaped by the urbanization and industrialization of England: Men were increasingly seen as a household’s main breadwinner and judged by their physical strength and courage. Brady (2005, p.22) describes these Victorian masculinity norms as hegemonic, in the sense that they “emphasised the authority of the paterfamilias over his wife and family, but also stigmatised masculine traits that undermined his position.”

Any traits and behavior that were not in line with the prevailing norms, such as same-sex sexual activity or effeminate behavior, were considered to undermine the patriarchical system. Indeed, this was exemplified by the strong condemnation of sexual encounters among male convicts by Australia’s colonial authorities. The authorities perceived homosexual activity to be widespread among convicts and worried that “In future years a moral stain of the deepest dye may be impressed, perhaps immovably, on its people, and thus become attached to the name of the Englishmen”, according to Norfolk convict department magistrate Pringle Stuart quoted in Hughes (2003, p.271).Footnote 18

The masculinity norms imported from Britain became rapidly interwoven with an emerging masculine identity that was shaped by the harsh reality of bush life for men without female companionship. Russel Ward’s influential book of Australian history traces the origins of the Australian legend or national mystique (Ward, 1958). This mystique, which is largely masculine in nature, is closely intertwined with the quintessential component of Australian male heritage called ‘mateship’. Mateship not only embodies equality, loyalty, and friendship between men (Pease, 2019) but also “a lack of emotional expression other than sharing jokes” (Edgar, 1997; p.79). Other features of this emerging Australian masculinity included heavy drinking, gambling, and, more recently, homophobia (Pease, 2019).Footnote 19

Ward (1958) argues that mateship and the emerging Australian masculine identity not only reflected the material conditions of pastoral life in the outback but also the fact that “the first and most influential bush-workers were convicts or ex-convicts, the conditions of whose lives were such that they brought with them to the bush the same, or very similar attitudes” (p.2). These masculinity norms became pervasive and persisted because “[t]he pastoral industry was, and still is, the country’s stable. Its nature, the nature of Australian geography, and the great though decreasing scarcity of white women in the outback, brought into being an itinerant rural proletariat, overwhelmingly masculine in composition and outlook.” (p.10). The emerging Australian masculine identity therefore effectively fused generic British masculinity norms with local values that reflected bush life and, in particular, the absence of female companions. It is this latter component that varied so starkly across Australia’s vast territory and that imprinted masculinity norms of different strength in different parts of the country.

Importantly, these spatially variegated masculinity norms then became further entrenched in the First World War, with the Anzac (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) as the leading exemplar of idealized masculinity. In particular, “According to the legend, the ‘heroic Anzac’ takes over from the ‘noble bushman’ as the embodiment of the ‘typical Australian’. The frontier masculinity is merged with that of the warrior, and mateship is re-configured for the trenches” (Murrie, 1998). In the patriotic rhetoric of the day, anyone who was not an Anzac, especially an eligible man who had chosen not to volunteer, could not claim the same manliness” (Dwyer, 1997).

4 Data

We combine various data sets on historical and modern-day Australia by matching the earliest possible historical Census in each state to: (i) WWI veterans; (ii) modern-day postcode- or local government area-level data on violence, crime, and mortality; (iii) modern-day nationally representative surveys of attitudes (HILDA) and of the lives and experiences of children (LSAC); (iv) present-day Census data on occupations; and (v) data on the 2017 referendum on same-sex marriage. The “online Appendix” provides a comprehensive list of all data sources and variable definitions.

4.1 Historical data

4.1.1 Convict sex ratios and balance tests

Our measure of the historical convict sex ratio comes from the first reliable Census in each state, as available from the Historical Census and Colonial Data Archive. We focus on the earliest possible Census in a state to measure convict population before the onset of mass migration, when convict shares of the population were highest. Although the population of Australia at the time was only about 255,000 people, 29% of the current population of Australia lives in areas covered by these historical data.

Only New South Wales (which included at the time what is now the Australian Capital Territory) and Tasmania were penal colonies. We use the 1836 New South Wales CensusFootnote 20 and the 1842 Tasmanian Census.Footnote 21 The unit of observation in the Census is a county.Footnote 22 34 counties harbored convicts. The average county had 3,446 individuals and most counties (about 95%) had between 300 and 10,000 people. The historical Censuses also contain data on economic occupations.

Table 1 displays descriptive statistics and shows how covariates are balanced by regressing each characteristic on the (standardized) convict sex ratio. Agriculture was the largest employment sector in Australia at the time, accounting for 24 percent of the labor force. Domestic services followed at 17 percent, and then manufacturing and mining with a combined total of 14%. The shares of people employed in these major sectors historically are not statistically related to the convict sex ratio (see Panel A of Table 1). Still, we control throughout our analysis for the historical shares of employment in different sectors, which may have influenced where colonial administrators assigned convicts.

For the same reason, we also control for land characteristics and mineral endowments, as counties with a high convict sex ratio tended to have more gold deposits and more rugged terrain. Figure 2 maps the convict sex ratio across New South Wales and Tasmania. The concentration of convicts of both sexes does not have a definite pattern: high and low sex ratios were found in the hinterland as well as along the coast.

Convict sex ratios in mid-19th century Australia. Notes: The maps show the parts of Australia that had convict settlement: Australian Capital Territory, New South Wales, and Tasmania. Boundaries depicted are for the 2016 Statistical Areas Level 1 (SA1), the smallest unit for the release of census data. Source: Australian Historical Censuses and Volume 1 of the Australian Statistical Geography Standard

4.1.2 Voluntary service in WWI

All recruits for WWI military service were volunteers. We use data from the 1933 Census on veterans who served in WWI as a proxy for voluntary enlistment in the first World War. 5.8% of men and 0.04% of women in 1933 report service in WWI. Digitized data on WWI enlistment linked to places of origin of volunteers is only available for Tasmania from Inwood et al. (2020). Using the presence of veterans in 1933 as a proxy for voluntary enlistment may suffer from measurement error due to survival bias, reporting bias, and post-war migration, which would be problematic if correlated with the convict sex ratio.

To gauge the extent of measurement error and the potential for it to be correlated with the convict sex ratio, we compare enlisted individuals and surviving veterans in 1933 at the level of 52 municipalities in Tasmania for which we have both sources of data. A comparison of the number of volunteers with the number of veterans implies a death rate of 18.3% between enlistment and 1933. This is very close to the actual military fatality rate, estimated for Tasmanian troops in WWI at 19.2% (Inwood et al., 2020). The correlation between enlisted volunteers and WWI veterans in 1933 is very high, at 0.95, suggesting limited measurement error. Combat rotation in WWI was organized at the level of brigades and battalions, which themselves were structured on a state basis.Footnote 23 State fixed effects would thus capture the main driver of fatality (that is, combat rotation to specific battles on specific days) limiting concerns about systematic correlation between fatality rates and local sex ratios.

We still check that the local difference between the number of veterans in 1933 and the number of men enlisted in WWI is uncorrelated with the convict sex ratio. The raw correlation coefficient (0.07) is small and statistically insignificant, suggesting limited roles played by selective fatality, misreporting, or migration.Footnote 24

4.2 Data on present-day outcomes

To explore the long-run effects of male-biased sex ratios, we use several data sources. First, we obtain crime statistics at the postcode level from the police or statistical agencies in respective states. As described in Sect. A.5 of the “online Appendix”, crime reporting varies across states but we are able to build consistent categories of crime between 2006 and 2016. We match these data to the 2006, 2011, and 2016 Census and interpolate the population between Census years to compute crime rates per capita.

Second, we use mortality statistics to obtain rates of death attributable to suicide and other forms of preventable mortality due to help avoidance. Data is from the Mortality over Regions and Time 2011–2015 data set (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare). The dataset lists the top 20 causes of death by gender and local government area (LGA) over this time period, as well as the total number of deaths in each year. Our main proxies for help avoidance behavior consist of mortality from prostate cancer and suicide. Moreover, a nationally representative survey, HILDA, gives us access to detailed and representative data on whether male respondents (aged 50+) had a prostate examination in the past twelve months.

Third, we use data from the 2011 and 2016 Census on the share of men and women across all 4-digit occupations. We first classify occupations into three groups: feminine, masculine, or neutral. To ensure that we pick up occupations that are known to be “stereotypically male/female”, we classify the most common occupations at the 4-digit level (occupations with total employment shares greater than 0.5%, approximately 55 of a total of 469 occupations, with 55% of the workforce represented in these occupations).

These common occupations are then considered feminine, neutral, or masculine if their national male share in the occupation is less than 33% (feminine), between 33 and 66% (neutral), or over 66% (masculine). Examples of the most masculine occupations are ‘Carpenters and Joiners’, ‘Metal Fitters and Machinists’, and ‘Motor Mechanics’ (all 99% male). Examples of the most feminine occupations are ‘Child carers’ (4.9% male), ‘Receptionists’ (5.2%), and ‘Education Aides’ (9.6%). Neutral occupations include ‘Real estate sale agents’ (50.0% male) and ‘Retail managers’ (50.5%).

Fourth, to measure the extent to which historical sex ratios have shaped attitudes towards homosexuals, we use the results of the 2017 referendum on same-sex marriage. The Australian Marriage Law Postal Survey was conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) as a postal vote. Unlike electoral voting, which is compulsory in Australia, responding to the survey was voluntary. A survey form was mailed to everyone on the electoral roll, asking the question "Should the law be changed to allow same-sex couples to marry?". Data is available at the level of 150 electoral districts. The results showed that 61.6% voted in favor of marriage equality across the country while 38.4% voted against it. Turnout was high, at 79.5%. While the postal survey was non-binding, the Liberal–National Coalition government had pledged to support a Parliamentary bill to legalize same-sex marriage in case of a "Yes" outcome. A few weeks after the vote, Australia’s House of Representatives voted in favor of legalizing same-sex marriage.

The district-level postal vote data provide us with a clean manifestation of masculinity norms, as negative attitudes towards sexual minorities are at the heart of such norms (Mahalik et al., 2003). The vote data are also unique in that they provide us with an ‘undiluted’ measure of people’s support for a salient normative cause (electoral voting would conflate these issues with many others, including economic considerations). Moreover, anonymous voting is not susceptible to response bias that can plague surveys. However, this data does not allow for individual comparisons.

To exploit individual variation, we also use HILDA, which identifies respondents through their residential postcode and contains a wide range of socio-demographic individual characteristics. Of interest is the question on attitudes towards the enfranchisement of sexual minorities: "Homosexual couples should have the same rights as heterosexual couples do". Answers range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), and we categorize individuals as broadly supportive of same-sex rights if they answered 4 (neutral) or above.

Fifth, we use survey measures of norms regarding help avoidance. We use data from Taking the Pulse of the Nation (TTPN), a repeated cross-sectional survey of 1200 adults carried out every two weeks between October 2020 and December 2021 about experiences with COVID-19. We use a question about willingness to get inoculated with a COVID-19 vaccine.Footnote 25 Masculinity norms have been highlighted as an obstacle to preventative measures against the spread of COVID-19: Men are less likely to wear a face covering than women and are more likely to associate wearing a covering with “weakness” (Capraro & Barcelo, 2020).

We also commissioned the Melbourne Institute to include the CMNI question that best predicts the outcomes that we study (i.e. violence, intimate partner violence, suicide attempts, doctor visits, see Table 8) in the latest HILDA survey round. This question asks on a five-point Likert scale whether the statement “It bothers me to ask for help" describes the respondent.

Lastly, to refine our understanding of possible socialization mechanisms that sustain the relationship between historical sex ratios and modern-day male identity and behavior, we use data on bullying in schools from a nationally representative survey of Australian youth (LSAC). LSAC is a longitudinal study of 10, 000 children, now teenagers, since 2003. It follows two cohorts (aged 0–1 in 2003–2004, and 4–5 in 2003–2004) and examines a broad range of questions on development and well-being. In particular, the survey measures the incidence of child bullying at school as reported by parents, children, and teachers. Due to a large number of missing observations from children’s reports we focus on responses by parents and teachers.

As explained before, we choose these outcomes as behavioral manifestations of norms of masculinity that are unrelated to male–female bargaining, or that even operate in domains in which the effect of male–female bargaining should go in the opposite direction as the effects of male–male competition. Our leading example is violence: we expect within-sex competition to select for violence as a mean of establishing oneself in the male hierarchy, while women would instead select cooperative men and turn away from violent men (who can be dangerous for themselves and for their children).

To examine this more formally, we calculate the correlation between these proxies for masculinity norms and proxies for gender norms that reflect male–female bargaining. To measure the latter, we focus on a HILDA survey question that GK use as a key proxy for the strength of gender-role norms influenced by male–female bargaining: the extent to which respondents agree that “It is better for everyone involved if the man earns the money and the woman takes care of the home and children”. As shown in Fig. 3 the proxies for masculinity norms that we use in this paper are largely uncorrelated with attitudes towards gender roles.Footnote 26

4.3 Data matching

To match present-day to historical data, we project all our data on the smallest geographic unit in the Census (SA1). We rely on the historical boundaries established by GK, which we project again at the SA1 level (as opposed to the larger postcode level used in GK). We then match all our outcome data to the 2011 or 2016 Census at the SA1 level and to the historical data. We match the 1933 Census data at the level of the smallest geographic area for which data is available, the local government area (LGA).

We retain the following SA1 characteristics from the Census as possible controls: present-day sex ratio, population, urbanization, religious composition, unemployment (by gender), education, age, and percentage Australian born. Across all specifications, controls are consistently measured at the SA1 level. We also collect data on minerals, soil quality, and land type from Geoscience Australia. Table 1 provides descriptive statistics. We present the balance of covariates in columns 3-4. There are no statistically significant differences of meaningful size across high versus low convict sex ratio areas in terms of present-day sex ratio, urbanization, age, male or female unemployment, income, or education. Of the 39 balance tests conducted in Table 1, four are statistically significant at the 10% level (of which two at the 5%), consistent with what we should expect to happen by chance.

5 Empirical strategy

We examine the long-term effects of male-biased sex ratios on present-day outcomes by estimating the following equation:

Where \(y_{ijcs}\) are outcomes for individual i in modern statistical area j (SA1, postcode, or LGA), part of historical county c, in state s. \(CSR_{cs}\) is the historical convict sex ratio: the number of male convicts to female convicts in historical county c in state s. We transform this variable into a z-score so that we can interpret the estimated coefficients as the impact of a one standard deviation increase in the historical convict sex ratio. \(\delta _s\) is a vector of state dummies. Outcomes are measured at the individual level, SA1 level, postcode, or LGA depending on data availability.

Since historical data at the level of historical counties is less granular than present-day data at the SA1 or individual level, we cluster standard errors at the historical county level. As only New South Wales and Tasmania were penal colonies, convicts were present in 34 historical counties. In “Appendix Table 9”, we correct our main estimates with the wild cluster bootstrap method based on 1,000 replications, following Cameron et al. (2008), to account for the limited number of clusters. We also consider the possibility that our results might (partially) reflect spatial autocorrelation in the residuals (Kelly, 2019). We present in “Appendix Table 9” Moran statistics that mitigate concerns that our results merely reflect spatial noise. Moreover, throughout all tables we report standard errors that are spatially heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation consistent (HAC-robust, cf. Conley (2010)).

\(X_{jcs}^G\) and \(X_{cs}^H\) are vectors of time-invariant geographic and historic characteristics that may correlate with the convict sex ratio and might still influence present-day outcomes. The need to develop the colony of Australia, chiefly in agriculture and mining, may have influenced where convicts were assigned. This could bias our estimates if initial economic specialization persisted over time and influences our outcomes of interest through its lasting influence on present-day conditions.

To flexibly account for geographic differences that may correlate with agricultural potential, we control for latitude and longitude of each postcode’s centroid. To control more precisely for mining and agricultural opportunities, we control for mineral deposits and land characteristics. We also control for county historical economic specialization by including in \(X_{cs}^H\) the shares of the population employed in the main categories of employment in 19th century Australia: agriculture, domestic services, mining and manufacturing, government, and learned professions. Total historical population in the county is also included in \(X_{cs}^H\).

\(T_{jcs}^C\) and \(X_{ijcs}^C\) are vectors of SA1-level and individual-level present-day controls. The full baseline controls account for 37% of the raw variation in the convict ratio, leaving 67% for identification (see also “Appendix Fig. 4”). Although present-day sex ratios and urbanization are uncorrelated with the historical convict sex ratio (Panel B of Table 1), these factors are important drivers of attitudes towards sexual minorities (Stephan & McMullin, 1982) and crime (Glaeser & Sacerdote, 1999). For this reason, we include controls for present-day sex ratio, population, and urbanization at the SA1 level.Footnote 27

A related concern is the potential influence of religion. Historically, there was little variation across counties in religious affiliation, with the main groups being evenly distributed across areas. In the 1836 New South Wales Census, 67% of the population was Protestant and 33% was Catholic, with a standard deviation of 0.13 for the two distributions across counties, and no statistically significant difference across high and low convict sex ratio areas. Today, we observe no statistically significant differences in the shares of main religions across high versus low convict sex ratio areas, (Panel B of Table 1), although the share of people who identify as Muslim is slightly lower in areas that had higher convict sex ratios. Still, because of the potentially large influence of religiosity on risk-taking, violent behavior and attitudes towards same-sex marriage, we will include the shares of religious groups at the SA1 level as additional controls in robustness tests (Sect. 7.1).

In the models using individual survey data, individual controls are gender, age, and whether the respondent was born in Australia. These characteristics do not vary systematically with the historical convict sex ratio (Panel C of Table 1). Present-day sex ratio, urbanization, unemployment for men or women, income, education, and age are also uncorrelated with the convict sex ratio (Panel B of Table 1, based on the Census). This suggests that the convict sex ratio was not systematically related to other characteristics that may influence present-day outcomes.

To identify a causal effect of the historical convict sex ratio in Eq. 5.1, we need to assume that the spatial distribution of the relative number of convict men and women was random, conditional on our proxies for economic opportunities and total population at the time. Convicts were not free to choose where to live, and were allocated centrally on the basis of observable characteristics. Using the sex ratio among convicts therefore alleviates the self-selection issue that free men and women chose their location based on unobservable preferences. That said, as discussed in the historical background section, convict assignment was not purely random but may also have been influenced by labor requirements. We remove this potential endogeneity bias by controlling for historical employment sector shares and for geographic factors, including the location of minerals and land type.

We choose to report reduced form estimates based on the sex ratio among convicts, rather than use the convict sex ratio as an instrumental variable for the historical population sex ratio, for two reasons.Footnote 28 First, our suggested mechanism is that the sex ratio shapes attitudes through its effect on mating competition. It should therefore only operate through the sex ratio among adults of reproductive age (ASR). However, the historical Censuses do not systematically break down the population by age, and many individual records have been destroyed, so that we cannot compute the ASR. The population sex ratio is thus a noisy measure of the treatment of interest. Convicts were generally of marriageable age, so that the sex ratio among convicts is a more precise proxy of an ASR. Second, while the convict sex ratio and the population sex ratio are highly correlated (\(\rho\) = 0.72) and our results are robust to an instrumental variable specification (Table 15), we believe the reduced form approach is statistically more appropriate given the sample size (Lee et al., 2020; Young, 2020).

Causal identification also requires that the convict sex ratio only influenced present-day outcomes through its effect on male-male competition. We have already discussed that male-biased sex ratios also influence male–female bargaining. However, as explained, the effects of sex ratios that are channeled through male–female bargaining are expected to, if anything, dampen our effects, causing us to underestimate the pure effect on male-male competition.

The presence of convicts itself may also have had a direct effect on health, crime and electoral outcomes today. Furthermore, it is possible that more hardened, risk-loving and violent convicts were systematically sent to more male-biased areas. Such endogenous selection could generate a correlation between, on the one hand, the convict sex ratio and, on the other hand, preferences for risk and violence stemming from convictism itself, which may have persisted until today. Historical evidence reduces this concern. First, as we describe in Sect. 3, convicts that were deported to Australia were not hardened criminals guilty of violent crime. Instead, they were mostly first-time offenders of petty property crime. Second, the placement of convicts was decided in a highly centralized way, making it unlikely that the spatial distribution was determined by unobservable taste for risk. Nevertheless, throughout all specifications we control for the number of convicts, together with total historical population. This absorbs the legacy of convictism as separate from the legacy of the sex ratio. To address the possibility that the relationship between the number of convicts and the sex ratio among convicts was not mean preserving, that is: only the more hardened, risk-loving and violent male convicts were systematically sent to more male-biased areas, we also perform our analysis with the total number of male convicts rather than the overall convict population.Footnote 29

6 Empirical results

This section first discusses the medium and long-term consequences of male-biased sex ratios on violence and crime; health; and occupational gender segregation. We then provide evidence from the 2017 same-sex marriage referendum.

6.1 Risk-taking: voluntary service in WWI

Military service in WWI was a risky endeavor. Fatality rates are estimated at 19.2% among Tasmanian recruits (Inwood et al., 2020), higher than those in the French military (estimated at around 16% (Gay, 2021)). Appeals to masculinity and the public shaming of unenlisted young men for their cowardice were key drivers of enlistment (Becker (2021), see also Fig. 5). We therefore expect a positive relationship between historical sex ratios and voluntary recruitment. We test this hypothesis and report the results in column 1 of Table 2. The estimates show that the rate of voluntary recruitment in WWI among men was significantly higher where the convict sex ratio had been more skewed. The point estimate indicates that a one standard deviation increase in the convict sex ratio is associated with a 5.6% increase in the share of men who volunteered to serve in WWI.

6.2 Violence, suicide, and health

We investigate the long-term consequences of male-biased sex ratios on violence in columns 2 and 3 of Table 2. Crime data are reported at the postcode level, which we project to the SA1 level. The dependent variables are the natural logarithm of the mean number of assaults and sexual offenses per 100,000 inhabitants between 2006 and 2016.

The estimates show that today, the rates of assault and sexual assault are higher in areas that were more male-biased in the past. The coefficient associated with the convict sex ratio is statistically significant at the 5% level for both assault and sexual assault. A one standard deviation increase in the convict sex ratio is associated with an 8.8% increase in the rate of assault and a 12.8% increase in sexual assaults.Footnote 30

We benchmark these effect sizes against the difference in the outcome by high versus low educational attainment (bottom 25% in high school completion rate vs top 25%). The log-difference in assault between high vs low education areas is 0.56, and our coefficient on the convict sex ratio represents 15.7% of this education gap. For sexual offenses, the coefficient on the convict sex ratio represents 23.7 per cent of this gap.

We investigate the long-term consequences of male-biased sex ratios on preventable male mortality in columns 1–3 of Table 3. The dependent variables are the (log) rates of mortality from suicide, broken down by gender, and from prostate cancer. The unit of observation is an LGA. All the results control for the usual historic, geographic, and present-day SA1 controls as well as total male deaths in columns 1 and 3 and total female deaths in column 2. We find strong and robust evidence of elevated rates of male— but not female—suicide and prostate cancer in formerly male-biased areas.

The magnitude of the results is large. For suicide—the main cause of death for Australian males under 45 years of age—a one standard deviation increase in the historical convict sex ratio is associated with a 20.2% increase in the male suicide rate. Given a baseline rate of 69.15 (per 100,000), this means that our result corresponds to approximately 14 additional suicide deaths per 100,000. The estimated coefficient corresponds to about 26% of the impact due to the education gap.

For prostate cancer, the most common cancer among men in Australia, the convict sex ratio is associated with a 3.3% increase in deaths, a magnitude corresponding to 8.5% of the education gap. This is likely driven, at least in part, by avoidance of preventative health behavior, in particular prostate cancer screenings which in Australia are recommended for all men over 50. Indeed, the results in column 4 of Table 3 show exactly this. We find that men from historically male-biased areas are 3.6% points (7.7% of the sample mean) less likely to have had a prostate cancer screening in the past 12 months.

Lastly, columns 5 and 6 of Table 3 provide evidence of the relationship between the convict sex ratio and preventative health behavior in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Masculinity ideals of strength, invincibility, and help avoidance are often invoked to explain differences between men and women in the takeup of preventative health measures (Springer & Mouzon, 2011) also in the context of COVID-19 vaccination (Capraro & Barcelo, 2020; Steinhauer, 2021). Table 3 shows that a one standard deviation increase in the historical convict sex ratio is associated with a 3.9% point increase in COVID vaccine hesitancy among men (column 5), with no effect on women (column 6). Given the high average vaccination takeup rates in Australia, this represents 18% of the mean vaccine hesitancy among Australian men (which lies at 22% in total).

6.3 Occupational gender segregation

To explore the relationship between historical sex ratios and occupational gender segregation, we regress, separately, the shares of men and women employed in 2011 and 2016 in feminine, neutral, and masculine occupations, as defined in Sect. 4.2. The first (last) three columns of Table 4 present the results for men (women).

Occupational gender segregation could reflect local norms guiding occupational choice as well as local economic conditions. However, the historical sex ratio is not systematically correlated with industrial composition historically (Table 1) nor at an intermediate point in time (1933, see Table 12) nor today (see columns 1 and 2 of Table 11). This suggests that local economic specialization only plays a minimal role. Moreover, to control directly for variation due to local labor market circumstances, we add to our usual covariates a control for total employment in masculine/neutral/feminine occupations at the postcode level. Our main coefficient of interest thus measures residual variation in how much the convict sex ratio explains of the share of workers (by gender) in a specific gender-stereotypical occupation, relative to the share of this occupation in the postcode.

The results paint a striking picture. Historical sex ratios significantly contribute to occupational gender segregation today. The coefficient associated with the convict sex ratio is significant for males across all categories of employment. The sign of the coefficient is consistent with our interpretation that historical sex ratios forged a culture of masculinity, which still leads men to seek employment in stereotypically male occupations, and to shun employment in stereotypically female, and even neutral, occupations.

Overall, a one standard deviation increase in the convict sex ratio is associated with a 0.7% point shift away in the share of men employed in neutral or stereotypically female occupations towards stereotypically male occupations.Footnote 31 We note, however, that the magnitudes here are more modest. For the share of men in masculine professions, our coefficient represents 3.2% of the education gap.

As men shun stereotypically female occupations, women may fill these jobs. Moreover, occupational segregation may not only threaten one’s own gender identity but also imply occupation-specific discrimination against the non-stereotypical sex. In other words, we also expect impacts on female occupational choice. Accordingly, the historical sex ratio is indeed significantly and positively associated with the share of women employed in female occupations (column 4). We now turn to a direct measure of masculinity norms by examining voting in the 2017 same-sex marriage referendum.

6.4 Support for same-sex marriage

Table 5 presents the estimation results using the share of votes in favor of same-sex marriage as the dependent variable in column 1 and the share of abstention in column 2. Abstention can be interpreted as the expression of a weaker form of opposition to same-sex marriage. After all, the status quo at the time of the referendum was that gays and lesbians were not allowed to marry. Abstaining thus meant maintaining that status quo. Indeed, several Members of Parliament who were opposed to same-sex marriage, expressed their intention to abstain and some constituents may have followed suit in this silent opposition.Footnote 32

We express votes and abstention as percentages of total voting population. That is, although “Yes" won more than 60% of all expressed suffrage, it only represented 47% of the total voting population, given the 20% abstention rate. We check the robustness of our results to another measure of attitudes towards same-sex marriage at the individual level from the HILDA survey, in which respondents are asked whether they agree that "Homosexual couples should have the same rights as heterosexual couples do" (columns 3 to 5).

The results show that both the share of votes in favor of marriage equality and the participation rate are substantially lower in areas where convict sex ratios were more male-biased in the past. A one standard deviation increase in the convict sex ratio is associated with a 2.2% point decrease in the vote share in favor of same-sex marriage (column 1). This amounts to 4.4% of the mean and corresponds to 39% of the education gap. We also observe that abstention, a lesser form of opposition to same-sex marriage, was significantly higher in areas that were more male biased in the past (column 2).

All of the controls—including all historical controls except for the convict sex ratio, our baseline controls, and the extended set of controls including education and religion—explain 61.1% of the variation in the “Yes” vote. Accounting for the convict sex ratio along with all the other controls explains 70.9% of the “Yes” vote. The convict sex ratio alone thus explains 9.8 percent of the variation in the “Yes” vote, and 25% (= 0.0982/0.3889) of the variation that is unexplained by a wide range of socio-demographic and economic factors, including religious background, unemployment, urbanization, and the present-day sex ratio, as well as historical factors such as total population and economic specialization.

The third column of Table 5 confirms these results with the individual-level survey data. Column 4 shows that men as well as women are more likely to oppose same-sex marriage in areas that were more male biased in the past.Footnote 33 This suggests that both genders have today internalized this norm and may be more likely to transmit it within families, as we investigate in Sect. 7 (where we also discuss the role of migration, cf. column 5).Footnote 34

6.5 Robustness

One might worry that our results (partially) reflect spatial autocorrelation in the residuals (Kelly, 2019). Throughout all tables, we therefore also display HAC-robust standard errors corrected for potential spatial correlation. All the results carry through. In addition, we calculate Moran statistics (a spatial version of the Durbin-Watson statistic) and report the related p values in Table 9 for each of our main estimates. These statistics suggest that correlation in spatial noise is limited and unlikely to drive our results. Moreover, we compute p-values based on the wild cluster bootstrap-t procedure, which accounts for the small number of clusters (Cameron et al., 2008). These p values are also reported in Table 9 and indicate that our results are not driven by inappropriate asymptotic assumptions.

We also present treatment effect bounds to gauge the quantitative importance of omitted unobservable factors (Table 9). We follow Oster (2019) and calculate bounds using a maximum R2 that is 1.3 times the R2 in the specification with all standard observable controls. The bounding set is then defined by the effect in the main specification with standard controls and the treatment effect under the assumption that observables are as important as unobservables. We find that the treatment effects are robust and that the bounding sets exclude zero.

In “Appendix Tables 9 and 10”, we subject our main results to additional robustness tests. Areas that received more male convicts could have followed a different development path in a way that is unrelated to masculinity norms but that could systematically explain our results. For example, if convicts were discriminated against in the labor market, had weaker preferences for education, or held different religious values, these characteristics could in turn have persisted and explain some of our results. We already discussed in Sect. 5 that areas with high versus low convict sex ratios are nowadays statistically indistinguishable from one another in terms of educational achievement, unemployment, and income.

In Table 9, we replicate our baseline results in the odd columns and contrast them with comparable specifications in the even columns that include additional present-day controls at the most granular (SA1) level. These are education (share of the local population that has completed year 12), unemployment rate (by gender), religion shares, median age, median household income, and the proportion of the local population born overseas. To the extent that these variables are endogenous to the convict sex ratio, they are bad controls and might bias our estimates. Table 9 shows that our results are robust to including these additional controls.

Lastly, we assess in “Appendix Table 10” the robustness to controlling for the distance of the SA1 to the nearest port (Panel A) and to controlling for whether an SA1 is part of a metropolitan area (Panel B). In Panel C, we trim the data by removing the two historical counties with the most and the least skewed convict sex ratio. All our results continue to hold.

7 Interpretation and mechanisms

So far, we have established a relationship between male-biased sex ratios in the 19th century and present-day outcomes for which we expect masculinity norms to play an important role: violence; suicide and help avoidance; occupational gender segregation; and opposition to sexual minorities’ rights. We now unpack what underlies this long-term relationship. First, we establish that our results reflect the persistent effect of masculinity norms. We do so by ruling out other explanations and by presenting direct evidence that masculinity norms constitute the mechanism that links historical sex ratios to present-day outcomes. Second, we investigate the strength of different persistence mechanisms that may explain the long-term impact of historical sex ratios.

7.1 Interpretation: masculinity norms or other factors?

7.1.1 Conservatism

The 2017 referendum on same-sex marriage was a politically charged event. Conservative political parties took position against legalization, and religious organizations were also heavily involved in the campaign. Is the relationship between historical sex ratios and present-day attitudes towards same-sex marriage really specific to attitudes towards homosexuality or merely a reflection of a legacy of sex ratios on social conservatism and political preferences more broadly?

Table 6 shows evidence in favor of the former: broad political attitudes, which go beyond the single issue of rights for homosexuals, are unaffected. Column 1 shows that the coefficient associated with the historical sex ratio does not have a significant effect on the share of votes for conservative partiesFootnote 35 in the general election in the year immediately preceding the same-sex marriage referendum. Hence, general conservatism cannot explain our results.

7.1.2 Crime in general

We argue that the historical sex ratio has forged a locally variegated culture of male violence. Column 2 of Table 6 shows that our earlier results on violent crime and male aggression are not driven by local differences in the prevalence of crime in general: the results show that rates of property crime are unrelated to the convict sex ratio.

Cultural underpinnings of violence will act very differently on premeditated versus non-premeditated crime. Assaults are mostly non-premeditated and often result from quickly escalating confrontations, often over what seems to the initiator of the assault as a grave insult to his masculinity or lack of respect (e.g., Wolfgang (1958); Goffman (1959); Wilson and Daly (1985)). Property crime is much more premeditated, less responsive to impulse, and more reflective of a calculation of costs and benefits (Pinker, 2011).

The differentiated long-term effect of sex ratios on assaults versus property crime is, in fact, similar to the situation in the US South, where the Scots-Irish culture of honor still contributes to high rates of homicide and assault, but not to other types of crime, such as property crime (Grosjean, 2014). It is therefore reassuring that we do not find evidence for more widespread crime in areas that were more male-biased in the past, but only evidence on violent crime, one of the costly manifestations of hegemonic masculinity.

7.1.3 Industrial composition

One potential mechanism of persistence may be industrial specialization. Although the convict sex ratio was not systematically correlated with industrial composition during the convict era (Table 1), heightened masculinity norms may have influenced industrial composition in the intermediate period. This could then have propagated masculinity norms to the present-day. However, using 1933 census data on employment in 21 industries, we do not find any evidence that convict sex ratios influenced industrial composition in the intermediate period (Table 12).

7.1.4 The China shock

In the U.S., the increase in deaths of despair (Case & Deaton, 2020), particularly among men, has been linked to the deterioration in economic circumstances partly caused by rising international manufacturing competition, especially from China (Autor et al., 2013, 2019). One may worry that spatial variation in the sensitivity of local male employment to the rise of China may confound the relationship between historical sex ratios and present-day manifestations of masculinity norms.

To investigate this, we follow Autor et al. (2013) and construct a granular measure of how exposed local male employment was in 1991 to the sudden increase in Chinese imports between 1992 and 2006. The Australian Census allows us to calculate, at the level of Local Government Areas (LGAs), the proportion of men employed in various industries in 1991, at the start of China’s rise to economic prominence.Footnote 36 We then multiply these initial LGA-level shares with subsequent increases in Australia-wide imports from China.

The results in columns 3 and 4 of Table 6 show that male employment in manufacturing in 1991 (column 3) and exposure to import competition from China (column 4) are both unrelated to the convict sex ratio. In line with this orthogonality, Table 11 shows that our main results are robust to controlling for local gender-specific import shocks due to China’s rapid emergence as an economic powerhouse.

7.1.5 Institutional differences and legislation