Abstract

This is a short tribute to Gordon Tullock, and the unique approach to bioeconomic issues that he took. The example used is hoarding behavior by various species of squirrels.

Similar content being viewed by others

I knew Gordon as a professor at the University of Virginia, a colleague at Virginia Tech and George Mason University, and as a co-editor of a volume of collected papers (Rowley et al. 1988). I was also a graduate student when Gordon taught at the University of Virginia. At Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, I occupied the office next to Gordon’s. There were many “Gordons.” There was the brash, young Tullock at University of Virginia whom I did not know. Then there was the more “mellow” Tullock at Virginia Tech and George Mason University whom I did know.

In the latter case Gordon was very helpful to younger scholars. In my view Gordon should have at least shared the 1986 Nobel Prize in Economics with his co-author James M. Buchanan (Buchanan and Tullock 1962) in their seminal book, The Calculus of Consent. In addition to his role in the Calculus, his papers on rent seeking (Tullock 1967) also qualified him for the Nobel Prize, as did his work on the economics of war and revolution (Tullock 1974). Alas, it was not to be. I think that I know some of the reasons, but that is beside the point now.

I know almost nothing about Gordon’s work in bioeconomics. I suppose to say that the bird eats the worm closest to it is a bioeconomic proposition. But there are other applications that I am sure would have attracted Gordon.

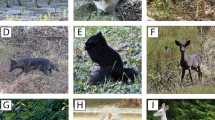

One is the field biology study of caching or savings behavior. Animals, such as squirrels, store food for winter consumption, as well as store surplus food. Economists treat saving as being positively related to the rate of interest. So the question becomes, what is the “natural rate of interest” exhibited by squirrels and does it bear a positive relationship to saving or caching? Field studies (see Vander Wall 1990) indicate that it is. For example, mast is acorn and nut production, and as the mast crop gets larger, squirrels adjust their savings to lower levels (see Brodin 2010).

The rate of interest in the squirrel economy is simply the ratio of the acorns stored to present consumption. Calculations of squirrel behavior indicate that the general interest rate is about 30 % (see Vander Wall 1990). This is high, but not so high as to be unbelievable. Some man-made economies exhibit higher rates, for example, some economies in Africa (see Brodin 2010).

There are also species of squirrels that have “central banking.” They store their acorns in the same place and not randomly. This suggests that complex issues must be solved, such as preventing theft and free riding behavior. Squirrels also exhibit optimizing behavior: they carry two nuts—rather than one nut at a time—in their mouth when squirrelling away their foragings.

This is just an example of how Gordon would have thought about a problem from field biology. I join my colleagues in honoring Gordon in his passing. As he used to say in a toast to the famous founder of public choice, Duncan Black, “he was the father of us all.”

References

Brodin, A. (2010). The history of hoarding studies. Philosophical Treatises B, 365(1542), 869–891.

Buchanan, J. M., & Tullock, G. (1962). The calculus of consent: Logical foundations of constitutional democracy. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press.

Rowley, C. K., Tollison, R. D., & Tullock, G. (Eds.). (1988). The political economy of rent-seeking. Bostosn, MA: Kluwer Academic Publisher.

Tullock, G. (1967). The welfare costs of tariffs, monopoliies, and theft. Western Economic Journal, 5(3), 224–232.

Tullock, G. (1974). The social dilemma: The economics of war and revolution. Blacksburg, VA: Center for Study of Public Choice.

Vander Wall, S. B. (1990). Food hoarding in animals. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tollison, R.D. Remembering Gordon Tullock. J Bioecon 18, 97–98 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10818-016-9227-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10818-016-9227-6