Abstract

Females of many Old World primates produce conspicuous vocalizations in combination with copulations. Indirect evidence exists that in Barbary macaques (Macaca sylvanus), the structure of these copulation calls is related to changes in reproductive hormone levels. However, the structure of these calls does not vary significantly around the timing of ovulation when estrogen and progestogen levels show marked changes. We here aimed to clarify this paradox by investigating how the steroid hormones estrogen and progesterone are related to changes in the acoustic structure of copulation calls. We collected data on semi-free-ranging Barbary macaques in Gibraltar and at La Forêt des Singes in Rocamadour, France. We determined estrogen and progestogen concentrations from fecal samples and combined them with a fine-grained structural analysis of female copulation calls (N = 775 calls of 11 females). Our analysis indicates a time lag of 3 d between changes in fecal hormone levels, adjusted for the excretion lag time, and in the acoustic structure of copulation calls. Specifically, we found that estrogen increased the duration and frequency of the calls, whereas progestogen had an antagonistic effect. Importantly, however, variation in acoustic variables did not track short-term changes such as the peak in estrogen occurring around the timing of ovulation. Taken together, our results help to explain why female Barbary macaque copulation calls are related to changes in hormone levels but fail to indicate the fertile phase.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Animal vocalizations provide important information about the vocalizer, including identity (Owren and Rendall 2003; Price et al. 2009; Rendall 2003; Rendall et al. 1998; Semple 2001) and caller attributes such as rank (Fischer et al. 2004; Harris 2006; Vannoni and McElligott 2008) and age, sex, and size (Ey et al. 2007). In addition, vocal behavior appears to be strongly influenced by reproductive hormones. For example, in male vertebrates, testosterone levels affect both the usage and structure of vocalizations, e.g., in fish (Fine et al. 2004; Remage-Healey and Bass 2005), frogs (Penna et al. 1992; Rhodes et al. 2007), birds (Arnold 1992; Balthazart and Ball 1995; Meitzen et al. 2007; Rybak and Gahr 2004; Smith et al. 1997; van Duyse et al. 2002), and nonhuman primates (Hollien 1960; Meitzen et al. 2007; Newman et al. 2000; Rybak and Gahr 2004; Saida et al. 1990; van Duyse et al. 2002), as well as ontogenetic development and short-term changes in vocal performance (Meitzen et al. 2007; Newman et al. 2000; Penna et al. 1992; Remage-Healey and Bass 2005; Smith et al. 1997; van Duyse et al. 2002).

Although many researchers report a relationship between acoustic structure and reproductive hormones in males, less is known for females. In women, voice characteristics such as frequency, harmonics, and intensity can change during the menstrual cycle (Abitbol et al. 1999; Brodnitz 1979). For example, fundamental frequency increases during high- vs. low-fertility days (Bryant and Haselton 2009), suggesting a role of estrogens in voice modulation. Further, changes in acoustic structure of the human female voice have also been reported after women enter menopause (Abitbol et al. 1999; Boulet and Oddens 1996; Caruso et al. 2000) and after hormone replacement therapy (Gerritsma et al. 1994; Lindholm et al. 1997). It is hypothesized that the structural modulation of the voice is the result of changes in the level of reproductive hormones eliciting hormone-dependent morphological changes in organs responsible for voice production, such as the vocal cords (Gerritsma et al. 1994) and larynx, tissues known to contain receptors for sex steroids (Newman et al. 2000; Saez and Sakai 1976; Voelter et al. 2008; cf. Schneider et al. 2007).

In nonhuman primates, the relationship between acoustic characteristics and reproductive hormones is largely untested. To date, most research has centered on female vocalizations that putatively serve to attract mates (estrus calls) or that are uttered during or immediately after copulation (copulation calls). For instance, in Tonkean macaques (Macaca tonkeana), the frequency of occurrence of female estrus calls correlates positively with estrogen levels (Aujard et al. 1998). In addition, studies in baboons and macaques have shown changes in temporal (using hormone measures to determine cycle state: Pfefferle et al. 2008a; using swelling size as indicator of cycle state: Deputte and Goustard 1980; O’Connell and Cowlishaw 1994; Semple et al. 2002) and spectral (using hormone measures to determine cycle state: Pfefferle et al. 2008a; using swelling size as indicator of cycle state: Semple and McComb 2000; Semple et al. 2002) parameters of female copulation calls during the course of the menstrual cycle, suggesting, at least indirectly, a relationship between reproductive hormones and the structure of these calls. Significantly, however, such variations in copulation call structure within the ovarian cycle do not, at least in Barbary macaques, seem to be temporally related to the time of ovulation, even though it is around this time that the most marked changes in both absolute and relative levels of estrogen and progesterone occur (Pfefferle et al. 2008a). Although interpretation of this finding is somewhat difficult, it does not necessarily exclude a relationship between call structural parameters and female reproductive hormones because other hormone-dependent modalities, such as female sexual behavior and anogenital swelling, also do not always change significantly around the time of ovulation (Engelhardt et al. 2005; Higham et al. 2009). Clearly, the existence, or otherwise, of a direct link between copulation call structure and levels of reproductive steroids in female Barbary macaques requires further investigation.

The investigation of this link is the objective of the present study, in which we extend our previous investigations of the functional significance of copulation calls in Barbary macaques. Previously, we postulated that in Barbary macaques, copulation calls act as a signal to the mating partner, influencing his likelihood of ejaculation (Pfefferle et al. 2008a), and also as a signal to other male group members, announcing a successful copulation (Pfefferle et al. 2008b) and thereby inciting the interest of other males in the calling female (Semple 1998). However, our inability to demonstrate a temporal relationship between call structure/frequency and ovulation raises the question as to whether hormonal changes during the periovulatory period of the female cycle are too small to induce a significant effect on the structural parameters of the call or whether any direct link between vocal parameters and reproductive hormone levels exists at all.

Accordingly, we examined the relationship between levels of female reproductive hormones and the structure of copulation calls in detail in 2 different situations: 1) within the time course of the normal ovulatory conception cycle and 2) during the postconception cycle, which refers to the temporally distinct period of increased sexual activity during early (usually within 2–6 wk) pregnancy, a phenomenon occurring in several macaque species, e.g., Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata: Nigi et al. 1990), pig-tailed macaques (Macaca nemestrina: Hadidian and Bernstein 1979), and long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis: Engelhardt et al. 2007) including Barbary macaques (Kuester and Paul 1984; Möhle et al. 2005). Postconception cycles are characterized by an increase in the estrogen-to-progestogen ratio that is qualitatively similar to that seen in conception cycles, but absolute levels of both hormones are markedly elevated in the postconception cycle (Möhle et al. 2005).

Here, we take advantage of this quantitative difference in endocrine profiles to examine whether and, if so, how changes in female estrogen and progestogen levels affect the vocal characteristics of female Barbary macaque copulation calls. Given our previous finding that there was no significant variation in call structure within females during the periovulatory period (Pfefferle et al. 2008a), we predict that estrogen and progestogen levels do not or only weakly correlate with the acoustic structure of Barbary macaque female copulation calls during the conception cycle. In contrast, because hormonal effects on biological functions are often dose dependent (Cooke et al. 2003; Phillippe et al. 1991) and because absolute hormone levels are markedly elevated during the postconception cycle (Möhle et al. 2005), the link between reproductive hormones and acoustic structure might be more easily detectable during this period of the female reproductive cycle. Thus, if acoustic parameters of female copulation calls are influenced by female reproductive hormone concentrations, we expect to find a clearer relationship between estrogen and progestogen levels and structural parameters of the calls in the postconception cycle vs. the conception cycle. In addition, we tested for differences in the structure of copulation calls in the conception and postconception cycles, to examine the influence of variation in absolute levels of reproductive hormones on vocalizations.

Materials and Methods

Study Site and Subjects

We studied 11 semi-free-ranging adult female Barbary macaques from 2 populations (Table I). The first, Middle Hill group, lived in the Upper Rock Nature Reserve in Gibraltar (Möhle et al. 2005). At the time of our study (mating seasons 2003–2004 and 2004–2005), this group consisted of 18–20 adult individuals, including 5–6 adult males and 13–14 adult females. The second population was housed in the La Forêt des Singes monkey park in Rocamadour, France (De Turckheim and Merz 1984). We studied 2 groups in La Forêt des Singes during the mating season 2005–2006. The Petit Bassin group consisted of 18 adult males and 29 adult females, and the Grand Bassin group consisted of 8 adult males and 21 adult females. Both study populations were health monitored and food provisioned. Subjects were habituated to human observers and individually recognizable using natural markings or tattoos. We analyzed 12 conception and 10 postconception cycles from the 11 focal females, which covered all rank and age classes (Table I) and were not on hormonal contraception.

Acoustic Recordings and Analysis

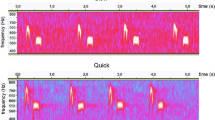

We recorded copulation calls from a distance of 2-4 m. We made recordings ad libitum with a sampling frequency of 44.1 kHz using either a SONY TCD-D100 DAT recorder (SONY Corporation, Japan) or a Marantz PMD 670 Professional Portable Solid State Flash Card Recorder (D & M Professional, Longford, UK) and a Sennheiser directional microphone (Sennheiser, Wedemark, Germany; K6 power module with Rycote Modular Windshield System and a Rycote Windjammer, Rycote, Stroud, U.K.). Overall, we collected 958 calls, of which 775 were of sufficient quality, e.g., not disturbed by any background noise, for acoustic analysis. Female Barbary macaque copulation calls are composed of a series of call units (Fig. 1), characterized by temporal and spectral parameters. Because units are short and reveal little to no frequency modulation, we focused on variables that describe the distribution of the amplitudes in the frequency spectrum (DFA) and the location of the dominant frequency bands (DFB) to describe the call spectrally. We calculated minimum, maximum, and mean values of the first and second amplitude quartiles (DFA1 and DFA2), as well as minimum, maximum, and mean values of the first and second dominant frequency bands (DFB1 and DFB2). In addition, we determined the minimum, maximum, and mean peak frequency (PF), which is the frequency of the highest amplitude in a certain time segment. We chose call duration as a temporal parameter, which describes the overall length of a call. Owing to a high degree of multicollinearity among the DFA, DFB, and PF parameters, we restricted our analysis to means, i.e., DFA2mean for DFA, DFB1mean for DFB, and PFmean for PF. These variables correspond to acoustic features used in previous analyses (Pfefferle et al. 2008a; Semple and McComb 2000), and have been shown to describe the call structure (Fischer 1998; Fischer et al. 1998; 2001; 2002; Neumann et al. 2010). Their salience is supported by playback studies showing the congruence between the macaques’ classification of sounds and classification based on these acoustic features (Fischer 1998). Further, this limited set of variables alleviates the problems associated with multiple testing. For more detailed information on how we assigned acoustic parameters see Pfefferle et al. (2008a), and for a description of the algorithms see Hammerschmidt (1990) and Schrader and Hammerschmidt (1997).

Fecal Sample Collection and Hormone Analysis

We collected a mean of 47 (range 30–70) fecal samples per focal female (mean: 1 sample every 1.8 d). We collected only fresh samples, which we homogenized with a wooden stick. We then placed 3–5 g of the fecal sample in a polypropylene tube containing 10 ml of absolute ethanol. At the end of the field period, we shipped all samples to the German Primate Center endocrine laboratory for hormone analysis. For this, we homogenized the samples in their solvent and extracted them twice according to the method described by Ziegler et al. (2000). The efficiency of this extraction procedure with Barbary macaque feces is 90% (Möhle et al. 2005). We measured fecal extracts for levels of immunoactive total estrogens (Etotal) and 5α-reduced 20-oxo pregnanes (5-P-3OH) using enzyme immunoassays that had been previously validated for monitoring ovarian endocrine function in Barbary macaques (Heistermann et al. 2008; Möhle et al. 2005). Sensitivity of the assays at 90% binding was 19.6 pg for 5-P-3OH and 3.9 pg for Etotal. Intra- and interassay coefficients of variation, calculated from replicate determinations of high- and low-value quality controls, were 8.2% (N = 16, 5-P-3OH), 7.9% (N = 16, Etotal; high) and 10.4% (N = 16, 5-P-3OH), 9.2% (N = 16, Etotal; low) and 18.7% (N = 102, 5-P-3OH), 16.6 % (N = 82, Etotal; high) and 16.2% (N = 102, 5-P-3OH), and 16.7% (N = 82, Etotal; low).

All females conceived during the study as indicated by maintenance of elevated 5-P-3OH levels beyond the length of a normal luteal phase. We determined the day of ovulation (= day of conception) for each female using the significant postovulatory 5-P-3OH rise (Heistermann et al. 2008). After determining the day of conception we backdated all hormone values by 2 d to adjust for the time lag between secretion of progesterone and estrogen in the blood and excretion of its metabolites into feces (Shideler et al. 1993). We based all subsequent analyses on these adjusted hormone values.

Data and Statistical Analysis

For each female we defined the period from the date of the first observed copulation (average 23.5 d before ovulation, range 14–32 d) to d 15 after conception as the conception cycle. The beginning of the postconception cycle is indicated by a vaginal bleeding occurring ca. 16 d after conception (Kuester and Paul 1984; Möhle et al. 2005), and is accompanied by a marked decline in progestogen levels and a marked rise in estrogen levels (Möhle et al. 2005; Fig. 2). The end of the postconception cycle is more difficult to define; we applied the definition of Kuester and Paul (1984), who used an average length of 28 d. Thus, d 16–44 after conception represents the postconception cycle.

Representative pattern of estrogen (Etotal) and progestogen (5-P-3OH) levels, and the time course of call duration (mean ± SD of the females recorded calls at a particular day) during the conception and postconception cycles of female JU (mating season 03/04). The occurrence of a value for call duration also indicates the occurrence of a copulation call on this particular day. The figure includes the 3-d time lag of the hormonal effect on copulation call occurrence and length, i.e., the acoustic data are shifted 3 d backwards.

Because of weather conditions and partial unavailability of individuals, we were unable to collect fecal samples every day. Because our time-scale analysis of the effect of hormonal changes on copulation call structure requires daily hormonal values, we interpolated missing hormonal data points using the aspline function of the akima package in R (Akima 1970, 1991a,b). To reduce the error resulting from short-term hormone fluctuations due to, e.g., food intake, stress, we smoothed the resulting curves of the individual hormonal data using the running median procedure in R (function = runmed, window size = 3; Cassidy et al. 1995; Gann et al. 2001; Mohr et al. 1996). All resulting hormone profiles were in accordance with previously published female Barbary macaque hormone profiles (Möhle et al. 2005). We used the resulting values in statistical analyses.

Influence of Steroid Hormones on Copulation Call Structure

We applied a linear mixed model to analyze the effect of the continuous variables estrogen and progestogen on the dependent continuous variables call duration, peak frequency (PFmean), distribution of the first dominant frequency band (DFB1mean), and distribution of the second dominant amplitude quartile (DFA2mean). We log10-transformed Etotal and 5-P-3OH measures to achieve normal distribution and included female ID as a random effect.

Because any modulating effect of hormones can be delayed up to several days (Losel and Wehling 2003), we checked for a possible time lag in the relationship between endocrine and acoustic parameters. We tested a time lag of 0 to ≤7 d, which covers the reported range hormones are known to need for exerting a biological effect (Gillman 1940; Losel and Wehling 2003; Sherwin and Gelfand 1987). We used the Akaike information criterion (AIC) to select from the set of models the one that best approximates the data, i.e., that best explains the effect of the 2 hormones on call structure. A lower AIC indicates that a model has a better fit than a higher value, controlling for the number of parameters in the model. Because the absolute hormone levels in a female’s conception and postconception cycles differ markedly and because the magnitude of the hormone change is much greater during the postconception cycle vs. the conception cycle (Möhle et al. 2005), we analyzed the types of cycles separately. We implemented the models in the R statistical computing environment (R Development Core Team 2008) using the glmer function (Bates 2005). The α level of statistical tests was 0.05.

Comparison of Copulation Calls Uttered During Conception and Postconception Cycles

To test whether acoustic parameters of copulation calls uttered during conception and postconception cycles differ, we compared acoustic values of the 2 cycle types. As temporal reference points for this comparison we chose the peak in estrogen preceding ovulation in the conception cycle and the clearly defined estrogen peak associated with the postconception cycle (Fig. 2 and Möhle et al. 2005). These periods of elevated estrogens represented times when mating activity was most pronounced and copulation calls most often given by the females (Fig. 2). We compared the acoustic structure during a 5-d window (day of estrogen peak ± 2 d) around both estrogen peaks using a linear mixed model (SPSS v. 19) incorporating female ID as random effect.

Results

Figure 2 depicts a representative time course of estrogen (Etotal) and progestogen (5-P-3OH) levels over a conception and a postconception cycle in relation to call duration in an individual female (JU, mating season 03/04). The 2 reproductive hormones follow the typical pattern described for Barbary macaques during the conception cycle and early pregnancy (cf. Möhle et al. 2005), with clearly elevated estrogen levels occurring in the preovulatory phase and between d 15 and 35 postconception and progestogen levels rising after ovulation and remaining elevated postconception.

Influence of Steroid Hormones on Copulation Call Structure

Levels of both estrogen (Etotal) and progestogen (5-P-3OH) were related to the structure of the copulation calls (Table II). The AIC model selection revealed a time lag of the hormonal effect on call structure of 3 d. No other time lag yielded significant results (Table II), although there was a trend for DFB1mean with a time lag of 1 d. The hormonal effects on the acoustic structure of copulation calls were most pronounced during the postconception cycle, when call duration, peak frequency, and the location of the second amplitude quartile were associated with the Etotal or 5-P-3OH level, or both (Table II). If the ratio between Etotal and 5-P-3OH was high, e.g., during the first half of the postconception cycle, copulation calls were longer (6.99 s) vs. periods when this ratio was low, e.g., during the second half of the postconception cycle (call duration = 4.05 s). Similarly, copulation calls uttered during the first half of the postconception cycle (high Etotal/5-P-3OH ratio) had a higher peak frequency (605 Hz) vs. those uttered during periods of low Etotal/5-P-3OH ratio (437 Hz). During the conception cycle, the only significant relationship found between hormones and call structure was the influence of Etotal on call duration (Table II), but the effect of 5-P-3OH levels on call duration was close to significant and negative.

Comparison of Copulation Calls Uttered During Conception and Postconception Cycles

There was no statistically significant difference in the acoustic structure of copulation calls uttered during the conception and postconception cycles (call duration: F(2,743) = 2.27, p = 0.104; DFA2mean: F (2,640) = 0.551, p = 0.58; DFB1mean: F (2,640) = 1.182, p = 0.307; PFmean: F (2,637) = 0.02, p = 0.981).

Discussion

Our results support the hypothesis that variation in levels of estrogens and progestogens affects the acoustic structure of female Barbary macaque copulation calls. The relationship between the 2 reproductive hormones and the structure of vocalizations was most pronounced in the postconception cycle, during which estrogen levels were, on average, 3 times higher than preovulatory levels in the conception cycle. Specifically, in the postconception cycle estrogens were positively related to call duration and frequency of the second amplitude quartile, whereas an increase in progestogen levels was related to a decrease in call duration and peak frequency. In comparison, only call duration was positively related to estrogen levels during the conception cycle, but none of the other changes in call parameters could be explained by variation in the levels of the 2 hormones. For the changes in call characteristics, we found a best fit when a time lag of 3 d between changes in hormone levels and acoustic parameters was taken into consideration. The fact that we found no difference in the structure of copulation calls between the conception and postconception cycles suggests that the observed acoustical changes are triggered by relative, rather than absolute, changes in hormone titers.

Although our findings are correlational and do not necessarily indicate causal relationships, they are generally consistent with results of other studies showing that reproductive hormones influence calling behavior and call structure, e.g., humans (Abitbol et al. 1999; Bryant and Haselton 2009; Gerritsma et al. 1994), nonhuman primates (Aujard et al. 1998), and birds (Arnold 1992; Balthazart and Ball 1995; Rybak and Gahr 2004). Interestingly, the relationship between the endocrine and the call parameters was stronger during the postconception vs. the conception cycle, indicating that the modulating effect of the 2 reproductive hormones on call characteristics differed between reproductive stages. The reason for this is not clear, but at least 2, possibly related, explanations exist. First, hormonal effects on biological functions are usually dose dependent (Cooke et al. 2003; Phillippe et al. 1991), and thus it is likely that the more pronounced change in the relative levels of reproductive hormones during the postconception cycle lead to more pronounced changes in call structure. Second, if, as in other vertebrate species, the regulation of calling behavior and characteristics is dependent on the number of steroid hormone receptors in vocal organs, pronounced acoustic changes might occur only after a certain threshold level of these receptors is reached. Reproductive hormone levels are consistently low in female Barbary macaques outside the breeding season, and because females usually conceive during their first cycle of the mating season (Kuester and Paul 1984; Möhle et al. 2005), they are exposed to elevated hormone levels (particularly estrogens) for only a couple of days during the conception cycle. We hypothesize that this time period may be too short to stimulate a sufficient up-regulation of hormone receptors or to induce the morphological changes in the sound production organs necessary for affecting call parameters. This might be particularly the case for spectral parameters whose production depends mainly on morphological changes in the phonation system, e.g., larynx, vocal cords. However, temporal parameters such as duration are mainly associated with alternations in the respiratory system, i.e., lungs, which should not depend (as much) on the hormonal state of the female. The observed relationship between the endocrine measures and call duration might therefore be indirect in the sense that the hormones affect the female’s motivation to call longer. Such an indirect effect on call duration may require lower levels of reproductive hormones than a direct influence on call structure, for which morphological changes in the phonation system are first needed. These potentially different endocrine thresholds may also explain why changes in call duration correlate with the endocrine milieu in both the conception and postconception cycles, whereas spectral variations in call structure are related to hormone levels only in the postconception cycle. However, based on the present results we are unable to disentangle the relative contribution and interactions of these different factors, mainly owing to the lack of sufficient measurements of a female’s motivational state.

Because steroid hormones generally act by modulating gene expression, their biological effect is usually delayed by hours or even several days (Gillman 1940; Losel and Wehling 2003; Sherwin and Gelfand 1987). Our data showing that a time lag of 3 d best explains the potential effect of the concentrations of the 2 hormones on the acoustic structure of the calls is consistent with this. Moreover, the observed time lag of hormonal action on calling structure is in the range of previously reported delays between endocrinological changes and downstream effects on other behaviors or morphological traits in vertebrates. For instance, the effect of progesterone on the deturgescence of female anogenital swelling size in baboons has a lag of 48 h (Gillman 1940), the initiation of menstrual bleeding occurs 90–96 h after progesterone administration (Gillman 1940), and the effect of estrogen on mounting behavior in rats is delayed by 7 d (D’Occhio and Brooks 1980). Similar time lag periods occur for testosterone action, e.g., treatment of women with testosterone leads to changes in female sexual interest after 1 wk (Sherwin and Gelfand 1987).

In terms of the function of Barbary macaque copulation calls, previous studies have demonstrated that copulation calls do not advertise the female fertile phase, but do affect mating outcome, i.e., ejaculation (Pfefferle et al. 2008a). Further, male Barbary macaques are able to distinguish between copulation calls uttered during ejaculatory and nonejaculatory copulations, with the former eliciting a stronger male response in terms of searching for the calling female (Pfefferle et al. 2008b). Thus, by stimulating male–male competition and increasing the number of male mating partners, copulation calls may be a means of promoting sperm competition/paternity confusion in this species. Though paternity confusion has been shown to reduce the risk of infanticide by males in several primate species (van Schaik et al. 2004), in Barbary macaques it may also set the stage for promoting extensive infant care from multiple males (Paul et al. 1992). This does not discount other hypotheses of copulation call function in other species with a different mating system, e.g., Guinea baboons (Papio papio), in which copulation calls occur after copulation, leading to increased male mate guarding (Maestripieri et al. 2005).

Because the structure of copulation calls uttered during the conception and postconception cycles does not differ, the acoustic modality cannot be used to discriminate these 2 cycle types. Although frequent copulations do occur during the postconception cycle, it remains to be investigated whether their performance is biased toward lower ranking or newly immigrated males, as in long-tailed macaques (Engelhardt et al. 2007). If this is the case, males that are familiar with the females may discriminate between conception and postconception cycles using other modalities, e.g., behavior, anogenital swelling, and odor. However, in Barbary macaques, it is difficult to envisage how such a capability would help males to increase reproductive success because females are not monopolized by specific males during the fertile phase (Brauch et al. 2008), and >75% females conceive during their first menstrual cycle (Kuester and Paul 1984; Möhle et al. 2005). The occurrence of postconception mating in general and the finding of no structural differences between copulation calls uttered during the conception and postconception cycles, together with a rather weak link between reproductive hormone levels and copulation call structure during the conception cycle and a pronounced time lag in the modulation of the call structure by the female endocrine milieu, support the hypothesis that copulation calls function more in the context of paternity confusion than in paternity assurance. Taken together, our data provide a plausible explanation as to why female Barbary macaque copulation calls are related to changes in hormonal levels but do not indicate the fertile phase.

References

Abitbol, J., Abitbol, A., & Abitbol, B. (1999). Sex hormones and the female voice. Journal of Voice, 13, 424–446.

Akima, H. (1970). A new method of interpolation and smooth curve fitting based on local procedures. Journal of the ACM, 17, 589–602.

Akima, H. (1991a). A method of univariate interpolation that has the accuracy of a 3rd-degree polynomial. Acm Transactions on Mathematical Software, 17, 341–366.

Akima, H. (1991b). Univariate interpolation that has the accuracy of a 3rd degree polynomial. Acm Transactions on Mathematical Software, 17, 367–367.

Arnold, A. P. (1992). Developmental plasticity in neural circuits controlling birdsong – sexual-differentiation and the neural basis of learning. Journal of Neurobiology, 23, 1506–1528.

Aujard, F., Heistermann, M., Thierry, B., & Hodges, J. K. (1998). Functional significance of behavioral, morphological, and endocrine correlates across the ovarian cycle in semifree ranging female tonkean macaques. American Journal of Primatology, 46, 285–309.

Balthazart, J., & Ball, G. F. (1995). Sexual-differentiation of brain and behavior in birds. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism, 6, 21–29.

Bates, D. (2005). Fitting linear mixed models in R using the lme4 package. R News, 5, 27–30.

Boulet, M. J., & Oddens, B. J. (1996). Female voice changes around and after the menopause – an initial investigation. Maturitas, 23, 15–21.

Brauch, K., Hodges, K., Engelhardt, A., Fuhrmann, K., Shaw, E., & Heistermann, M. (2008). Sex-specific reproductive behaviours and paternity in free-ranging Barbary macaques (Macaca sylvanus). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 62, 1453–1466.

Brodnitz, F. S. (1979). Menstrual-cycle and voice quality. Archives of Otolaryngology - Head & Neck Surgery, 105, 300–300.

Bryant, G. A., & Haselton, M. G. (2009). Vocal cues of ovulation in human females. Biology Letters, 5, 12–15.

Caruso, S., Roccasalva, L., Sapienza, G., Zappala, M., Nuciforo, G., & Biondi, S. (2000). Laryngeal cytological aspects in women with surgically induced menopause who were treated with transdermal estrogen replacement therapy. Fertility and Sterility, 74, 1073–1079.

Cassidy, A., Bingham, S., & Setchell, K. (1995). Biological effects of isoflavones in young women – importance of the chemical composition of soybean products. The British Journal of Nutrition, 74, 587–601.

Cooke, B. M., Breedlove, S. M., & Jordan, C. L. (2003). Both estrogen receptors and androgen receptors contribute to testosterone-induced changes in the morphology of the medial amygdala and sexual arousal in male rats. Hormones and Behavior, 43, 336–346.

De Turckheim, G., & Merz, E. (1984). Breeding Barbary macaques in outdoor open enclosures. In J. F. Fa (Ed.), The Barbary Macaque: A case study in conservation (pp. 241–261). New York: Plenum Press.

Deputte, B. L., & Goustard, M. (1980). Copulatory vocalisations of female macaques (Macaca fascicularis): Variability factors analysis. Primates, 21, 83–99.

D’Occhio, M. J., & Brooks, D. E. (1980). Effects of androgenic and estrogenic hormones on mating-behavior in rRams castrated before or after puberty. The Journal of Endocrinology, 86, 403–411.

Engelhardt, A., Hodges, J. K., Niemitz, C., & Heistermann, M. (2005). Female sexual behavior, but not sex skin swelling, reliably indicates the timing of the fertile phase in wild long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis). Hormones and Behavior, 47, 195–204.

Engelhardt, A., Hodges, J. K., & Heistermann, M. (2007). Post-conception mating in wild long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis): Characterization, endocrine correlates and functional significance. Hormones and Behavior, 51, 3–10.

Ey, E., Pfefferle, D., & Fischer, J. (2007). Do age- and sex-related variations reliably reflect body size in non-human primate vocalizations? A review. Primates, 48, 253–267.

Fine, M. L., Johnson, M. S., & Matt, D. W. (2004). Seasonal variation in androgen levels in the oyster toadfish. Copeia, 2004(2), 235–244.

Fischer, J. (1998). Barbary macaques categorize shrill barks into two call types. Animal Behaviour, 55, 799–807.

Fischer, J., Hammerschmidt, K., & Todt, D. (1998). Local variation in Barbary macaque shrill barks. Animal Behaviour, 56, 623–629.

Fischer, J., Hammerschmidt, K., Cheney, D. L., & Seyfarth, R. M. (2001). Acoustic features of female chacma baboon barks. Ethology, 107, 33–54.

Fischer, J., Hammerschmidt, K., Cheney, D. L., & Seyfarth, R. M. (2002). Acoustic features of male baboon loud calls: influences of context, age, and individuality. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 111, 1465–1474.

Fischer, J., Kitchen, D. M., Seyfarth, R. M., & Cheney, D. L. (2004). Baboon loud calls advertise male quality: acoustic features and their relation to rank, age, and exhaustion. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 56, 140–148.

Gann, P. H., Giovanazzi, S., Van Horn, L., Branning, A., & Chatterton, R. T. (2001). Saliva as a medium for investigating intra- and interindividual differences in sex hormone levels in premenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 10, 59–64.

Gerritsma, E. J., Brocaar, M. P., Hakkesteegt, M. M., & Birkenhager, J. C. (1994). Virilization of the voice in postmenopausal women due to the anabolic-steroid nandrolone decanoate (decadurabolin) – the effects of medication for one-year. Clinical Otolaryngology, 19, 79–84.

Gillman, J. (1940). The effect of multiple injections of progesterone on the turgescent perineum of the baboon (Papio porcarius). Endocrinology, 26, 1072–1077.

Hadidian, J., & Bernstein, I. S. (1979). Female reproductive cycles and birth data from old world monkey colony. Primates, 20, 429–442.

Hammerschmidt, K. (1990). Individuelle Lautmuster bei Berberaffen (Macaca sylvanus): Ein Ansatz zum Verstaendnis ihrer vokalen Kommunikation. Ph.D. thesis, Freie Universitaet Berlin.

Harris, T. R. (2006). Within- and among-male variation in roaring by black and white colobus monkeys (Colobus guereza): What does it reveal about function? Behaviour, 143, 197–218.

Heistermann, M., Brauch, K., Mohle, U., Pfefferle, D., Dittami, J., & Hodges, K. (2008). Female ovarian cycle phase affects the timing of male sexual activity in free-ranging Barbary macaques (Macaca sylvanus) of Gibraltar. American Journal of Primatology, 70, 44–53.

Higham, J. P., Semple, S., MacLarnon, A., Heistermann, M., & Ross, C. (2009). Female reproductive signaling, and male mating behavior, in the olive baboon. Hormones and Behavior, 55, 60–67.

Hollien, H. (1960). Some laryngeal correlates of vocal pitch. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 3, 52–58.

Kuester, J., & Paul, A. (1984). Female reproductive characteristics in semifree-ranging Barbary macaques (Macaca sylvanus L. 1758). Folia Primatologica, 43, 69–83.

Lindholm, P., Vilkman, E., Raudaskoski, T., SuvantoLuukkonen, E., & Kauppila, A. (1997). The effect of postmenopause and postmenopausal hrt on measured voice values and vocal symptoms. Maturitas, 28, 47–53.

Losel, R., & Wehling, M. (2003). Nongenomic actions of steroid hormones. Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology, 4, 46–56.

Maestripieri, D., Leoni, M., Raza, S. S., Hirsch, E. J., & Whitham, J. C. (2005). Female copulation calls in guinea baboons: Evidence for postcopulatory female choice? International Journal of Primatology, 26, 737–758.

Meitzen, J., Moore, I. T., Lent, K., Brenowitz, E. A., & Perkel, D. J. (2007). Steroid hormones act transsynaptically within the forebrain to regulate neuronal phenotype and song stereotypy. The Journal of Neuroscience, 27, 12045–12057.

Möhle, U., Heistermann, M., Dittami, J., Reinberg, V., Hodges, J. K., & Wallner, B. (2005). Patterns of anogenital swelling size and their endocrine correlates during ovulatory cycles and early pregnancy in free-ranging Barbary macaques (Macaca sylvanus) of Gibraltar. American Journal of Primatology, 66, 351–368.

Mohr, P. E., Wang, D. Y., Gregory, W. M., Richards, M. A., & Fentiman, I. S. (1996). Serum progesterone and prognosis in operable breast cancer. British Journal of Cancer, 73, 1552–1555.

Neumann, C., Assahad, G., Hammerschmidt, K., Perwitasari-Farajallah, D., & Engelhardt, A. (2010). Loud calls in male crested macaques, Macaca nigra: a signal of dominance in a tolerant species. Animal Behaviour, 79, 187–193.

Newman, S. R., Butler, J., Hammond, E. H., & Gray, S. D. (2000). Preliminary report on hormone receptors in the human vocal fold. Journal of Voice, 14, 72–81.

Nigi, H., Hayama, S. I., & Torii, R. (1990). Copulatory behavior unaccompanied by ovulation in the Japanese monkey (Macaca fuscata). Primates, 31, 243–250.

O’Connell, S. M., & Cowlishaw, G. (1994). Infanticide avoidance, sperm competition and mate choice – the function of copulation calls in female baboons. Animal Behaviour, 48, 687–694.

Owren, M. J., & Rendall, D. (2003). Salience of caller identity in rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) coos and screams: perceptual experiments with human (Homo sapiens) listeners. Journal of Comparative Psychology, 117, 380–390.

Paul, A., Kuester, J., & Arnemann, J. (1992). DNA fingerprinting reveals that infant care by male Barbary macaques (Macaca sylvanus) is not paternal investment. Folia Primatologica, 58, 93–98.

Penna, M., Capranica, R. R., & Sommers, J. (1992). Hormone-induced vocal behavior and midbrain auditory-sensitivity in the green treefrog, Hyla cinerea. Journal of Comparative Physiology A: Sensory Neural and Behavioral Physiology, 170, 73–82.

Pfefferle, D., Brauch, K., Heistermann, M., Hodges, J. K., & Fischer, J. (2008). Female Barbary macaque (Macaca sylvanus) copulation calls do not reveal the fertile phase but influence mating outcome. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 275, 571–578.

Pfefferle, D., Heistermann, M., Hodges, J. K., & Fischer, J. (2008). Male Barbary macaques eavesdrop on mating outcome: a playback study. Animal Behaviour, 75, 1885–1891.

Phillippe, M., Saunders, T., & Bangalore, S. (1991). A mechanism for testosterone modulation of alpha-1 adrenergic-receptor expression in the ddt1 mf-2 smooth-muscle myocyte. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry, 100, 79–90.

Price, T., Arnold, K., Zuberbuhler, K., & Semple, S. (2009). Pyow but not hack calls of the male putty-nosed monkey (Cercopithcus nictitans) convey information about caller identity. Behaviour, 146, 871–888.

Remage-Healey, L., & Bass, A. H. (2005). Rapid elevations in both steroid hormones and vocal signaling during playback challenge: a field experiment in gulf toadfish. Hormones and Behavior, 47, 297–305.

Rendall, D. (2003). Acoustic correlates of caller identity and affect intensity in the vowel-like grunt vocalizations of baboons. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 113, 3390–3402.

Rendall, D., Owren, M. J., & Rodman, P. S. (1998). The role of vocal tract filtering in identity cueing in rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) vocalizations. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 103, 602–614.

Rhodes, H. J., Yu, H. J., & Yamaguchi, A. (2007). Xenopus vocalizations are controlled by a sexually differentiated hindbrain central pattern generator. The Journal of Neuroscience, 27, 1485–1497.

Rybak, F., & Gahr, M. (2004). Modulation by steroid hormones of a “sexy” acoustic signal in an oscine species, the common canary Serinus canaria. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, 76, 365–367.

Saez, S., & Sakai, F. (1976). Androgen receptors in human pharyngo-laryngeal mucosa and pharyngo-laryngeal epithelioma. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry, 7, 919–921.

Saida, H., Okamoto, H., Imaizumi, S., & Hirose, H. (1990). A study of voice mutation and physical growth – a longitudinal observation. Nippon Jibiinkok Gakkai Kaiho, 93(4), 596–605.

Schneider, B., Cohen, E., Stani, J., Kolbus, A., Rudas, M., Horvat, R., et al. (2007). Towards the expression of sex hormone receptors in the human vocal fold. Journal of Voice, 21, 502–507.

Schrader, L., & Hammerschmidt, K. (1997). Computer-aided analysis of acoustic parameters in animal vocalisations: a multi-parametric approach. Bioacoustics: The International Journal of Animal Sound and Its Recording, 7, 247–265.

Semple, S. (1998). The function of Barbary macaque copulation calls. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 265, 287–291.

Semple, S. (2001). Individuality and male discrimination of female copulation calls in the yellow baboon. Animal Behaviour, 61, 1023–1028.

Semple, S., & McComb, K. (2000). Perception of female reproductive state from vocal cues in a mammal species. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 267, 707–712.

Semple, S., McComb, K., Alberts, S. C., & Altmann, J. (2002). Information content of female copulation calls in yellow baboons. American Journal of Primatology, 56, 43–56.

Sherwin, B. B., & Gelfand, M. M. (1987). The role of androgen in the maintenance of sexual functioning in oophorectomized women. Psychosomatic Medicine, 49, 397–409.

Shideler, S. E., Shackleton, C. H. L., Moran, F. M., Stauffer, P., Lohstroh, P. N., & Lasley, B. L. (1993). Enzyme immunoassays for ovarian-steroid metabolites in the urine of Macaca fascicularis. Journal of Medical Primatology, 22, 301–312.

Smith, G. T., Brenowitz, E. A., Beecher, M. D., & Wingfield, J. C. (1997). Seasonal changes in testosterone, neural attributes of song control nuclei, and song structure in wild songbirds. The Journal of Neuroscience, 17, 6001–6010.

van Duyse, E., Pinxten, R., & Eens, M. (2002). Effects of testosterone on song, aggression, and nestling feeding behavior in male great tits, Parus major. Hormones and Behavior, 41, 178–186.

van Schaik, C. P., Pradhan, G. R., & van Noordwijk, M. A. (2004). Mating conflict in primates: Infanticide, sexual harassment and female sexuality. In P. Kappeler & C. P. van Schaik (Eds.), Sexual selection in primates new and comparative perspectives (pp. 131–150). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vannoni, E., & McElligott, A. G. (2008). Low frequency groans indicate larger and more dominant fallow deer (Dama dama) males. PLoS ONE, 3(9), 1–8.

Voelter, C., Kleinsasser, N., Joa, P., Nowack, I., Martinez, R., Hagen, R., et al. (2008). Detection of hormone receptors in the human vocal fold. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, 265, 1239–1244.

Ziegler, T., Hodges, J. K., Winkler, P., & Heistermann, M. (2000). Hormonal correlates of reproductive seasonality in wild female hanuman langurs (Presbytis entellus). American Journal of Primatology, 51, 119–134.

Acknowledgment

For permission to enter the study areas, cooperation, and support we thank the Royal Air Force Gibraltar, Eric Show, Ellen Merz, and Géròme Lagarrigue. Ellen Merz kindly made the demographic data for Rocamadour available. We thank Ralf Brockhausen for discussion and help with the data analyses; Kurt Hammerschmidt for making his sound analyses program (LMA) available; and Andrea Heistermann, Katrin Brauch, and Kornelius Kimmich for help with the hormone analyses. For valuable comments on the manuscript we thank the editor and 2 anonymous referees. This work was supported by the German Science Foundation (to J. Fischer and J. K. Hodges).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Pfefferle, D., Heistermann, M., Pirow, R. et al. Estrogen and Progestogen Correlates of the Structure of Female Copulation Calls in Semi-Free-Ranging Barbary Macaques (Macaca sylvanus). Int J Primatol 32, 992–1006 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-011-9517-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-011-9517-8