One bad apple don’t spoil the whole bunch, girl. Donny Osmond.

Abstract

Previous research demonstrates that individuals vary in their social preferences. Less well-understood is how group composition affects the behavior of different social preference types. Does one bad apple really spoil the bunch? This paper exogenously identifies experimental participants’ social preferences, then systematically assigns individuals to homogeneous or heterogeneous groups to examine the impact of ‘bad apples’ on cooperation and efficiency. Consistent with previous research, we find that groups with more selfish types achieve lower levels of efficiency. We identify two mechanisms for the effect. First, the selfish players contribute less. Second, selfish players induce lower contributions from the conditional cooperators, and this effect increases in the number of selfish players. These results are not sensitive to information about the distribution of types in the group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A notable exception is Burlando and Guala (2005), though their focus is on homogeneous groups.

In a replication of FGF using several locations in Russia, Herrmann and Thöni (2009) find the share of conditional cooperators varies between 47.7 and 60.0 % and that the share of Nash/selfish types varies between 1.9 and 11.4 %. Kocher (2006) finds approximately 35 % of the population to be conditional cooperators and that, given the option, subjects choose to condition on the responses of others 56 % of the time. Martinsson et al. (2009) find conditional cooperators randing from 54.2 to 62.5 % of their sample while free riders range from 4.2 to 25.0 %. For Kurzban and Houser (2005) type elicitation mechanism and population, the respective percentages are 20 % Nash/selfish and 63 % conditional cooperators. For Burlando and Guala (2005), these percentages are 32 and 35 % respectively.

As stated by the authors: “It was made clear that the composition of the groups differed from that of the first session” (p. 44). However, there is no mention of whether this meant subjects knew the group composition was homogeneous, or just that these were different groups than those in the first session.

To avoid feedback effects, for subjects participating in the lab-study, earnings are picked up or delivered on the day of their participation, after their session is completed. For those not participating in the lab study, earnings are picked up or delivered (via the university debit card) after the lab study is complete.

Specifically, we classify subjects who never give more than five as selfish. In the 21 decisions of the type elicitation task, over 90 % of the decisions for our selfish subjects are zeroes, and over 98 % are either zero or one.

There are no significant differences in demographics by information treatment at p < 0.05, except the following: Asian (p = 0.01). Due to difficulty recruiting the required number of the various types of subjects, a limited number of experienced subjects (19) were recruited.

This was done to confirm that there was no impact of telling an individual their own type, which there was not (p = 0.80, from a t test of means comparing the one-shot game and the first round of the repeated-play game in the No Information treatment). This result further hold when considering only selfish (p = 0.45) or conditional cooperator (p = 0.75) types.

Several other types of decision rules which might readily come to the subjects’ mind are listed, even though they are not of interest for this study. This was done to minimize demand effects.

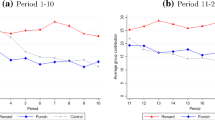

Estimated as a random effects regression where the dependent variable is the amount of tokens sent, as a function of the round, treatment, an interaction between the round and treatment, and the constant.

Modeled as a random effects Tobit regression using only the conditional cooperators in the sample, allowing for censoring at zero and twenty. The dependent variable is the amount of tokens sent to the group account, modeled as a function of the round, information treatment, dummy variables for the (C, C, S) and (C, S, S) groupings, plus a constant. The (C, C, C) grouping is the omitted dummy variable. See Appendix Table 5.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for raising this issue and suggesting some of these important ideas.

References

Ahn, T. K., Ostrom, E., & Walker, J. M. (2003). Heterogeneous preferences and collective action. Public Choice, 117(3–4), 295–314.

Andreoni, J. (2006). Philanthropy. In S. C. Kolm & M. Ythier (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of giving, altruism and reciprocity (pp. 1201–1269). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Andreoni, J., & Croson, R. (2008). Partners versus strangers: Random rematching in public goods experiments. In C. R. Plott & V. L. Smith (Eds.), Handbook of experimental economics results (pp. 776–783). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Ashley, R., Ball, S., & Eckel, C. (2010). Motives for giving: A reanalysis of two classic public goods experiments. Southern Economic Journal, 77(1), 15–26.

Axelrod, R. (1984). The evolution of cooperation. New York: Basic Books.

Boyd, R., & Richerson, P. J. (2004). The origin and evolution of cultures. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brandts, J., & Schram, A. (2001). Cooperation and noise in public goods experiments: Applying the contribution function approach. Journal of Public Economics, 79(2), 399–427.

Burlando, R. M., & Guala, F. (2005). Heterogeneous agents in public goods experiments. Experimental Economics, 8(1), 35–54.

Camerer, C., & Fehr, E. (2004). measuring social norms and preferences using experimental games: A guide for social scientists. In J. Henrich, R. Boyd, S. Bowles, C. Camerer, E. Fehr, & H. Gintis (Eds.), Foundations of human sociality: Economic experiments and ethnographic evidence from fifteen small-scale societies (pp. 55–95). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Croson, R. T. A. (1996). Partners and strangers revisited. Economics Letters, 53(1), 25–32.

Croson, R. T. A. (2007). Theories of commitment, altruism and reciprocity: Evidence from linear public goods games. Economic Inquiry, 45(2), 199–216.

Dietz, T., Ostrom, E., & Stern, P. C. (2003). The struggle to govern the commons. Science, 302(5652), 1907–1912.

Fischbacher, U., & Gachter, S. (2010). Social preferences, beliefs, and the dynamics of free riding in public good experiments. American Economics ReviewS, 100(1), 541–556.

Fischbacher, U., Gächter, S., & Fehr, E. (2001). Are people conditionally cooperative? evidence from a public goods experiment. Economics Letters, 71(3), 397–404.

Gächter, S., & Thöni, C. (2005). Social learning and voluntary cooperation among like-minded people. Journal of the European Economic Association, 3(2–3), 303–314.

Gunnthorsdottir, A., Houser, D., & McCabe, K. (2007a). Disposition, history and contributions in public goods experiments. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 62(2), 304–315.

Gunnthorsdottir, A., Vragov, R., & McCabe, K. (2007). The meritocracy as a mechanism to overcome social dilemmas. Munich Personal RePEc Archive No. 2454.

Herrmann, B., & Thöni, C. (2009). Measuring conditional cooperation: A replication study in Russia. Experimental Economics, 12(1), 87–92.

Kocher, M. (2006). Conditional cooperation in public goods experiments and its behavioral foundations. Working Paper.

Kurzban, R., & Houser, D. (2001). Individual differences in cooperation in a circular public goods game. European Journal of Personality, 15(S1), S37–S52.

Kurzban, R., & Houser, D. (2005). Experiments investigating cooperative types in humans: A complement to evolutionary theory and simulations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102(5), 1803–1807.

Ledyard, J. (1995). Public goods: A survey of experimental research. In A. E. Roth & J. H. Kagel (Eds.), The handbook of experimental economics (Vol. 1). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Martinsson, P., Villegas-Palacio, C., & Woolbrant, C. (2009). Conditional cooperation and social group-experimental results from Colombia. Environment for Development Discussion Paper Series No. EfD DP 09-16.

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ostrom, E. (2000). Collective action and the evolution of social norms. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 14(3), 137–158.

Ostrom, E., Burger, J., Field, C. B., Norgaard, R. B., & Policansky, D. (1999). Revisiting the commons: Local lessons, global challenges. Science, 284(5412), 278–282.

Page, T., Putterman, L., & Unel, B. (2005). Voluntary association in public goods experiments: Reciprocity, mimicry and efficiency. The Economic Journal, 115(506), 1032–1053.

Richerson, P. J., & Boyd, R. (2008). Not by genes alone: How culture transformed human evolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ross, L., & Nisbett, R. E. (1991). The person and the situation: Perspectives from social psychology. New York: McGraw Hill.

Zetland, D., & Della Giusta, M. (2011). Focal points, gender norms and reciprocation in public good games. Working Paper.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Sunny Kukreja and Thomas Sires for programming this experiment and Elizabeth Pickett for her managerial magic. Abdul Kidwai provided research support. Additionally, we would like to thank Daniel Arce, Nathan Berg, Chetan Dave, Sherry Xin Li, James Murdoch, Todd Sandler and participants at the Negotiation Center at the University of Texas at Dallas, Social Dilemmas Conference at Rice University, International Association for the Study of the Commons Annual Meeting 2010, the Economic Science Association North American Regional Meetings, Southern Economic Association Annual Meetings, Allied Social Science Association Annual Meetings, and SITE 2009 Segment 7 for helpful comments. Funding provided by the Center for Behavioral and Experimental Economic Science at the University of Texas at Dallas (now closed). Any errors remain our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Oliveira, A.C.M., Croson, R.T.A. & Eckel, C. One bad apple? Heterogeneity and information in public good provision. Exp Econ 18, 116–135 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-014-9412-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-014-9412-1