Abstract

We conduct a high-resolution large-eddy simulation (LES) case study in order to investigate the effects of surface heterogeneity on the (local) structure parameters of potential temperature \(C_T^2\) and specific humidity \(C_q^2\) in the convective boundary layer (CBL). The kilometre-scale heterogeneous land-use distribution as observed during the LITFASS-2003 experiment was prescribed at the surface of the LES model in order to simulate a realistic CBL development from the early morning until early afternoon. The surface patches are irregularly distributed and represent different land-use types that exhibit different roughness conditions as well as near-surface fluxes of sensible and latent heat. In the analysis, particular attention is given to the Monin–Obukhov similarity theory (MOST) relationships and local free convection (LFC) scaling for structure parameters in the surface layer, relating \(C_T^2\) and \(C_q^2\) to the surface fluxes of sensible and latent heat, respectively. Moreover we study possible effects of surface heterogeneity on scintillometer measurements that are usually performed in the surface layer. The LES data show that the local structure parameters reflect the surface heterogeneity pattern up to heights of 100–200 m. The assumption of a blending height, i.e. the height above the surface where the surface heterogeneity pattern is no longer visible in the structure parameters, is studied by means of a two-dimensional correlation analysis. We show that no such blending height is found at typical heights of scintillometer measurements for the studied case. Moreover, \(C_q^2\) does not follow MOST, which is ascribed to the entrainment of dry air at the top of the boundary layer. The application of MOST and LFC scaling to elevated \(C_T^2\) data still gives reliable estimates of the surface sensible heat flux. We show, however, that this flux, derived from scintillometer data, is only representative of the footprint area of the scintillometer, whose size depends strongly on the synoptic conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

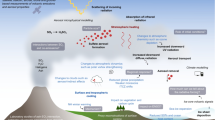

The turbulent surface fluxes of sensible and latent heat play an important role in the vertical transport of energy and water vapour in the atmospheric boundary layer (ABL). The measurement of the area-averaged fluxes at a regional scale is necessary both for a better understanding of the meteorological and hydrological processes as well as for the validation of parametrizations in numerical weather prediction (NWP) and climate models (De Bruin et al. 1993; Li et al. 2012; Beyrich et al. 2012; Braam et al. 2012). The grid resolution in NWP models is usually of the size of several km. For heterogeneous surfaces, it is thus essential to measure surface fluxes that are representative of an area of the order of a few km\(^{2}\). Over homogeneous terrain, point measurements using the eddy-covariance technique are the traditional and most common means of determining the surface fluxes (Andreas 1991; Lee et al. 2004; Braam et al. 2012). Natural landscapes rarely provide horizontally homogeneous conditions such that the grid boxes in NWP models often contain different surface patches of farmland, settlements, water, forest, etc. The local surface fluxes of the different surface types, however, might differ significantly (e.g. Bange et al. 2006; Beyrich et al. 2006) and local point measurements over all relevant land-use types would be necessary to derive area-averaged surface fluxes based on a suitable averaging strategy (Gottschalk et al. 1999; Beyrich et al. 2006). This requires considerable experimental effort.

As an alternative, scintillometry offers a technique that allows for estimating the surface sensible and latent heat fluxes by measuring turbulent density fluctuations in the surface layer in terms of the refractive index structure parameter \(C_n^2\) as a line average over horizontal distances of up to 10 km (e.g. Kohsiek et al. 2002; Meijninger et al. 2002b, a, 2006; Evans et al. 2012, inter alia). Hill (1978), for example, showed that \(C_n^2\) is related to the structure parameters of temperature, \(C_T^2\), humidity, \(C_q^2\), and the cross-structure parameter \(C_{Tq}\), since the density fluctuations are dominantly caused by fluctuations of temperature and humidity. The relative contribution of both depends on the electromagnetic wavelength. Temperature fluctuations are absolutely dominant for optical and near-infrared electromagnetic wave propagation, except for very moist conditions, while both temperature and humidity fluctuations are relevant for millimetre waves except for very dry conditions.

Provided that the ABL is neither extremely moist or dry, temperature fluctuations are absolutely dominant for optical and near-infrared electromagnetic wave propagation, while both humidity and temperature fluctuations are relevant for millimetre waves. As a consequence, an optical large-aperture scintillometer (LAS) can be used to determine path-averaged values of \(C_T^2\), and a microwave scintillometer (MWS) in combination with LAS can provide both \(C_T^2\) and \(C_q^2\) (e.g. Kohsiek and Herben 1983; Meijninger et al. 2002a, 2006; Lüdi et al. 2005). In order to determine the surface sensible and latent heat fluxes from the estimates of \(C_T^2\) and \(C_q^2\), respectively, Monin–Obukhov similarity theory (MOST) is applied.

Theoretically, the application of MOST is limited to horizontally homogeneous surfaces (Andreas 1991; Beyrich et al. 2012). The application of MOST for structure parameters over a heterogeneous surface thus requires that the height of the measurement is above a blending height for structure parameters, where any signal from the present surface heterogeneity is no longer visible in the sampled turbulence field (Wieringa 1976; Mahrt 2000; Meijninger et al. 2002b; Sühring and Raasch 2013). In this way, the measurement sees a virtually homogeneous surface that incorporates all heterogeneity effects. So far the blending height concept and its existence has been discussed controversially in the literature (e.g. Meijninger et al. 2002b; Bange et al. 2006; Sühring and Raasch 2013).

Meijninger et al. (2002b) estimated the blending height for \(C_T^2\) to be not higher than 14 m during the Flevoland field experiment based on measurements. In contrast, the large-eddy simulation (LES) study of Sühring and Raasch (2013) over the moderately heterogeneous LITFASS area in eastern Germany suggested a clear dependence of the turbulent fluxes on the underlying surface type up to the top of the convective boundary layer (CBL). We might hence consider surface heterogeneity to be a significant factor that might lead to a decorrelation between scintillometer-derived surface fluxes from a LAS or MWS path and the area-averaged surface fluxes for a domain of several km\(^{2}\) around this scintillometer path. This, however, has not been demonstrated so far, but Beyrich et al. (2006) found reasonable agreement between LAS/MWS and aggregated eddy-covariance surface fluxes over the LITFASS area.

While structure parameters are traditionally defined for statistically homogeneous and isotropic fields, they can also be defined as a local and time-dependent quantity within a chosen volume of air so long as an inertial subrange is present (e.g. Cheinet and Siebesma 2009). Recently, van den Kroonenberg et al. (2012) employed small unmanned aircraft to study the variability of the local estimates of \(C_T^2\) along a LAS path during the LITFASS-2009 experiment. They found a noticeable variability of \(C_T^2\) along the path and ascribed this to both temporal variations as well as to the underlying surface heterogeneity. However, Sühring and Raasch (2013) pointed out that sufficient independent flight measurements are required to obtain a significant estimate of a heterogeneity-induced effect in terms of turbulent fluxes. The question, as to whether there is a heterogeneity-induced effect on \(C_T^2\) and \(C_q^2\) and their local estimates in the surface layer and if this can be measured by aircraft (and scintillometers), is still open.

LES is a promising technique for studying the effect of surface heterogeneity on the structure parameters and their MOST relationships. Unlike in situ measurements, where the (heterogeneous) surface fluxes are basically unknown, they can be explicitly prescribed in the LES model. Previous LES studies have shown that vertical profiles and local estimates of \(C_T^2\) and \(C_q^2\) can be reliably derived from LES data for the homogeneously-heated CBL (Peltier and Wyngaard 1995; Cheinet and Siebesma 2009; Cheinet and Cumin 2011; Wilson and Fedorovich 2012; Maronga et al. 2013b). Cheinet and Siebesma (2009) studied the spatial variability of \(C_T^2\) and found a bimodal log-normal distribution in the lower boundary layer, which was previously also found in the Sodar measurements of Petenko and Shurygin (1999). Cheinet and Cumin (2011) studied the behaviour of \(C_T^2\) and \(C_q^2\) in the entrainment-drying CBL and found that the distribution of \(C_q^2\) was determined by entrained air parcels from the free atmosphere, whereas \(C_T^2\) was dominated by near-surface convective plumes. Cheinet and Siebesma (2007) used a wave propagation modelling framework to derive the scintillation rate and coherence length from virtual path measurements in their LES. They found that the variability of their virtual measurements of \(C_n^2\) increased with height, while the path mean \(C_n^2\) decreased. However, the coarse spatial resolution of their LES did not allow study of the wave propagation at realistic scintillometer heights on the order of 50 m, since they could not resolve the surface layer.

A first comparison of LES with in situ aircraft and LAS data was performed by Maronga et al. (2013b). They also employed virtual LAS (VLAS) measurements in their LES at realistic heights between 30 and 70 m above the ground to investigate the temporal and spatial variability of \(C_T^2\) measurements using a LAS, and confirmed the results of Cheinet and Siebesma (2007). Maronga (2014) calculated the MOST relationships for structure parameters from a set of LES runs ranging from near-neutral to the free convective ABL above a homogeneous surface and found that universal MOST functions exist for \(C_T^2\) that were well within the range of proposed functions. Maronga (2014) also showed that entrainment of dry air at the top of the mixed layer explains the dissimilarity between the turbulent transport of heat and moisture and leads to non-universal similarity functions for \(C_q^2\). Up to now, all LES studies have been performed for idealized conditions with homogeneous surfaces and under quasi-stationary conditions. The question whether MOST for structure parameters is also valid over heterogeneous terrain with different surface patches that provide different characteristics concerning surface fluxes and roughness has not been studied by means of LES so far.

Maronga and Raasch (2013a) simulated the CBL over the heterogeneous LITFASS-2003 terrain (see Fig. 1a), based on the former LES runs of Uhlenbrock et al. (2004), for four selected days during the LITFASS-2003 experiment (see Beyrich and Mengelkamp 2006). They found that secondary circulations developed that were superimposed on the randomly distributed convection, partly taking over the vertical transport of heat and moisture. However, they showed that the scale of the surface heterogeneity must be at least of the size of the ABL depth \(z_{i}\) to induce such circulations that then span the entire CBL. This agrees with Shen and Leclerc (1995) and Raasch and Harbusch (2001) for idealized two-dimensional surface heterogeneities. Sühring and Raasch (2013) used the LITFASS set-up and showed that LES is an appropriate tool for investigating the blending height concept.

Distribution of land-use classes: a shows the entire LITFASS area where the black box marks the LES model domain for case LIT2E and the white dashed box indicates the model domain for case LIT2E_W. b Shows a close-up view of the model domain for case LIT2E, including the VLAS path (black line) from Falkenberg (GM) to Lindenberg (MOL). The legend indicates the percentage coverage of the particular land-use class in the model domain

In the present case study the CBL over the eastern part of the LITFASS-2003 area (see Fig. 1a, b, dominated by farmland) is simulated by high-resolution LES runs using the model PALM. The structure parameters are for the first time derived from surface-layer turbulence resolving LES over such an irregular surface heterogeneity, and they are compared with LAS measurements performed during the LITFASS-2003 experiment. The concept of a blending height for structure parameters is studied using a lagged two-dimensional correlation analysis method. Moreover, we discuss if MOST can be applied over such heterogeneous landscapes, and explore possible implications of surface heterogeneity on LAS observations.

The paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 describes the LES model PALM, model set-up as well as data processing. Section 3 outlines the derivation of structure parameters from LES data, and a brief introduction to the MOST relationships for structure parameters is given. Simulation results are presented in Sect. 4, and Sect. 5 gives a summary.

2 LES Model, Set-up and Case Description

2.1 LES Model

The LES model PALM (revision 1105) (see e.g. Raasch and Schröter 2001; Riechelmann et al. 2012) has been used in the present study. It has been recently applied to study different flow regimes in the CBL over homogeneous (e.g. Raasch and Franke 2011; Maronga et al. 2013b) and heterogeneous terrain (e.g. Maronga and Raasch 2013a; Sühring and Raasch 2013). All simulations were carried out using cyclic lateral boundary conditions. The grid was stretched in the vertical direction well above the top of the ABL in the free atmosphere to save computational time. MOST was applied as a surface boundary condition locally between the surface and the first computational grid level (“local similarity model”, see also Peltier and Wyngaard 1995), including the calculation of the local friction velocity \(u_*\). A 1.5-order flux-gradient subgrid closure scheme after Deardorff (1980) was applied (see also Moeng and Wyngaard 1988; Saiki et al. 2000), which requires the solution of an additional prognostic equation for the subgrid-scale (SGS) turbulent kinetic energy. It should be noted that previous LES studies suggested that such static SGS models can lead to deficiencies near the transition boundaries of surface heterogeneity (e.g. Stoll and Porté-Agel 2006, 2008). We tried to minimize such effects by using a high grid resolution that allows for resolving the bulk part of the turbulence in the atmospheric surface layer (see below). A fifth-order advection scheme of Wicker and Skamarock (2002) and a third-order Runge–Kutta timestep scheme were used (Williamson 1980). A one-dimensional version of the model with fully parametrized turbulence, using a mixing-length approach after Blackadar (1997) and stationary temperature and humidity profiles, was used for precursor simulations to generate steady-state wind profiles as initialization for the LES runs.

2.2 Model Set-up and Case Description

This case study is based on the LES set-up for the heterogeneous LITFASS area on 30 May 2003 as described in Maronga and Raasch (2013a). We follow their nomenclature and hereafter refer to this case as LIT2E, where 2E refers to the prescribed geostrophic wind of 2 m s\(^{-1}\), with wind direction from the east. Case LIT2E was characterized by clear skies. Maronga and Raasch (2013a) showed that their LES results were in good agreement with the radiosonde data from the LITFASS-2003 experiment concerning the representation of the mean boundary-layer structure. Figure 1a shows the land-use types in the LITFASS area derived from the CORINEFootnote 1 dataset with a resolution of 100 m. The size of the area was about 20 km \(\times \) 20 km, containing different surface patches of forest, lakes and farmland, as was used in the previous LES studies. These studies, however, had relatively coarse grid resolutions of 40–100 m in all spatial directions. In order to resolve turbulence in the surface layer, a much higher grid resolution was required in the present study. Due to limited computing resources it was necessary to limit the model domain to an area of 5.3 km \(\times \) 5.3 km with \(1600 \times 1600\) grid points in the horizontal directions, resulting in a horizontal grid resolution of 3.3125 m (Fig. 1a, black box and Fig. 1b). In early test runs we found that the vertical profiles of \(C_T^2\) and \(C_q^2\) from different calculation methods (see below) converge at a grid resolution of 5 m, so that the grid resolution of the present study is an adequate choice for studying structure parameters. From the previous LES studies we found that the mean boundary-layer depth \(z_{i}\) reached about 1.8 km at 1400 UTC, and hence used a constant vertical grid resolution of 2 m up to a height level of 2 km. Above, the grid was vertically stretched by a factor of 1.02 for each plane so that the vertical model extension was about 3.7 km. Moreover, the simulation time was reduced to that part of the diurnal cycle from 0500 UTC to 1300 UTC. In this way one simulation still required about 120 h of real time on 4096 Intel Xeon Gainestown processors (2.93 GHz) on an SGI Altix ICE 8200 Plus cluster. In order to quantify effects of the surface heterogeneity, a second run with a homogeneous surface but temporally-varying surface forcing (hereafter case HOM, see Fig. 2 and below) was performed. A third simulation, hereafter referred to as LIT2E_W, was performed for sensitivity tests (see Sect. 4.4) where the model domain was shifted 1.5 km westwards (see Fig. 1a, white dashed box).

Time series of the prescribed surface fluxes of a sensible and b latent heat for the different land-use classes as well as the horizontal average (solid red line) as used in the homogeneous control run. The data are complemented by the VLAS flux footprint (solid black line) calculated each hour as described in Sect. 3.4

In the course of the LITFASS-2003 experiment, LAS observations were made along a 4.8-km long path at an effective height of 43 m above the ground (following topography), extending from the boundary-layer field site (GM) of the German Meteorological Service (DWD) near Falkenberg to the Lindenberg Meteorological Observatory (MOL) (see Beyrich and Mengelkamp 2006). We located the model domain around the LAS path as shown in Fig. 1b with the start and finish of the VLAS measurement path in the LES being located on grassland. The height of the VLAS was 41 m and thus equal to the height of the LAS (see above). The LAS path was nearly aligned in north-south direction. For simplification we decided to align the VLAS path exactly along the \(y\)-direction in the model, which should not introduce a significant error since the heterogeneity was still prescribed on a 100 m raster. A footprint analysis was carried out afterwards for LIT2E to retrospectively ensure that the chosen model domain was large enough to cover the footprint source area of the VLAS. The results of this footprint analysis will be discussed in Sect. 3.4. Figure 1b shows that the surface in the model domain mainly consists of different agricultural fields, where triticale makes up 39 % of the total area. The remaining area is covered by maize (17 %), rape (16 %), forest (11 %, including settlements, see Maronga and Raasch 2013a), grassland (10 %) and barley (7 %). No open water surfaces occur in the area chosen for this study. Therewith, the distribution of surface types is significantly different from the previous LES runs for the LITFASS area and hence also the area-averaged surface fluxes differ.

The orography in the LITFASS area is rather flat and thus neglected in the LES runs. Initial vertical profiles of potential temperature \(\theta \) and specific humidity \(q\) up to the top of the model domain were derived from radiosonde observations during the LITFASS-2003 experiment (see Maronga and Raasch 2013a, their Fig. 3). Since no large-scale advection was present, the lapse rate in the free atmosphere was determined from radiosonde data obtained near the beginning of the simulation and kept constant in time (see Sect. 4.1). An aerodynamic roughness length \(z_0\) for the different surface types was estimated as \(z_0 \approx 0.1 h\), \(h\) being crop height (see e.g. Shuttleworth et al. 1997). Local surface sensible and latent heat fluxes (\(H = \rho c_p \overline{w'\theta '}_0\) and \(LE = \rho L_\mathrm{v} \overline{w'q'}_0\), respectively, with \(c_p\) being the heat capacity of dry air at constant pressure and \(L_\mathrm{v}\) being the latent heat of vaporization) were measured during LITFASS-2003 at energy balance stations located on the different land-use types. Figure 2 shows the diurnal cycle of these measured fluxes until 1300 UTC, illustrating that the forest patches generated the largest surface sensible heat flux with values of up to 500 W m\(^{-2}\), followed by barley and triticale (up to 300 W m\(^{-2}\)) and grass, maize as well as rape (up to 220 W m\(^{-2}\)). The surface latent heat flux only displayed a weakly developed diurnal cycle with maximum fluxes of 220 W m\(^{-2}\) (rape). In agreement with the former LES of the LITFASS area, we prescribed the locally measured fluxes to the LES surface following the distributions given in Fig. 1b. The flux data were available for 30-min intervals and were thus linearly interpolated in time for each timestep. As in our former LES studies of the LITFASS area, we used measured surface-flux data that represent the energy input into the atmosphere and that drive the turbulence. These flux data already incorporate effects of the plant canopy, such as transpiration, so that a surface-vegetation-atmosphere-transfer model was not required. The quality of such a model would anyway strongly depend on the quality of input data such as root depth and leaf area indices, which are very difficult to determine. This is particularly true for a heterogeneous area of several km\(^{2}\). For a more detailed discussion of the implementation of the heterogeneity we refer to Maronga and Raasch (2013a) and Sühring and Raasch (2013). For case HOM we aggregated the locally measured fluxes to the LES domain area-averaged flux.

Examples of the footprints for the VLAS, derived from the LES data using the analytical footprint model of Kormann and Meixner (2001), mapped on land-use classes. The contour lines indicate the cumulative footprint areas of 90 % (blue line) and 50 % (brown line). See Fig. 1 for colour coding of surface types. a 0800 UTC. b 1000 UTC. c 1200 UTC

Close scrutiny of the LITFASS-2003 data, however, unfortunately revealed that we did not use the composite fluxes derived from all available energy balance stations over the same surface type by Beyrich et al. (2006) (see their Fig. 5), but rather the eddy-covariance fluxes from individual energy balance stations. These forcing data provide too strong a forcing compared to the composite fluxes and have been used for several years during LES of the LITFASS area (Uhlenbrock et al. 2004; Maronga and Raasch 2013a; Sühring and Raasch 2013). Depending on the land-use type and time of the day, the deviation between the composite fluxes and the used fluxes was up to 104 W m\(^{-2}\) for sensible heat (forest) and 69 W m\(^{-2}\) for latent heat (barley). The area-averaged surface flux displayed a difference in the course of the day of 10–50 W m\(^{-2}\) for both sensible and latent heat. The inconsistency in the data had not been discovered before, mainly because the simulated ABL still compared well with observations. We discuss the effect of this too strong a forcing later in Sect. 4. Due to high computational demands it was neither feasible to perform more than the present case study, nor was it possible to repeat a simulation with an improved set-up. In the present study this issue restricts the direct validation of VLAS measurements with the in situ LAS data. Moreover, we might expect that mean profiles e.g. of temperature and humidity, as well as those of structure parameters, can be altered slightly. Fortunately, the other analyses included in this and the former studies should not be significantly affected by the inaccurate fluxes.

Maronga and Raasch (2013a) showed that secondary circulations developed over the LITFASS area, depending on the geostrophic wind, and that a sufficiently large upwind buffer zone is required in order to resolve them. However, these secondary circulations only develop if the heterogeneity scales are at least of size \(z_{i}\), and if there are strong constrasts in the surface characteristics (as between forest and water) (e.g. Shen and Leclerc 1995). Over the eastern part of the LITFASS area (dominated by farmland patches with a size in the order of 1 km) the heterogeneity scales are usually too small and the heterogeneity amplitude is too low to trigger secondary circulations (see Maronga and Raasch 2013a, their Fig. 5a). Moreover, Maronga and Raasch (2013a) pointed out that secondary circulations are generally weak close to the surface. Effects of such circulations, such as a modification of the turbulent vertical fluxes of heat and moisture, are thus expected to be irrelevant for the present study. Local small-scale effects of the surface heterogeneity, however, remain and will be most prominent in the lower ABL.

The ABL depth was calculated from the \(\theta \) profile following Sullivan et al. (1998), and was found to increase in the course of the simulation up to 1.5 km. The top of the surface layer \(z_\mathrm{SL}\) was defined as \(z_\mathrm{SL} = 0.1 z_{i}\), following e.g. Brasseur and Wei (2010), noting that \(z_\mathrm{SL}\) indicates the height up to which MOST roughly should be valid. In order to study the MOST relationships for \(C_T^2\) and \(C_q^2\) we thus only used data from height levels below \(z_\mathrm{SL}\). Moreover, as pointed out by Khanna and Brasseur (1997), the lowest levels are always affected by the SGS model and thus cannot resemble the surface-layer dynamics correctly. We hence excluded the lowest seven grid points from the analysis of the MOST relationships as suggested by Maronga (2014). Due to the very high vertical resolution of 2 m used in our simulations, the entire surface layer is represented by more than \(40\) grid points (except the early morning hours before the morning inversion is eroded, see below), so that omitting the lowest levels does not restrict our analysis of the surface layer much.

3 Theory and Methods

3.1 Structure Parameters

Traditionally, the structure parameters of temperature and humidity are defined and deduced either directly using the structure functions, or using the one-dimensional spectra of temperature and humidity (e.g. Tatarskii 1971; Wyngaard et al. 1971b; Andreas 1988). As both formulations are mathematically equivalent, we focus on the latter approach. Following Wyngaard et al. (1971b) the structure parameters \(C_T^2\) and \(C_q^2\) are directly proportional to the spectral density of temperature and humidity in the inertial subrange respectively, and can be related to the power spectral density \(\varPhi \) (spectral method) at a given height by

where the given scalar \(S\) can be either \(\theta \) or \(q\); \(k\) is a wavenumber in the inertial subrange and \(0.2489 = (2/3)\varGamma (1/3)\) after Muschinski et al. (2004). Note that for potential temperature the notation \(C_{T}^2\) with index \(T\) (actual temperature) is used for convenience.

In the recent LES study of Cheinet and Siebesma (2009) \(C_T^2\) and \(C_q^2\) were calculated from the relationship between the (local) dissipation rates of turbulent kinetic energy \(\varepsilon _\mathrm{TKE}\) and scalar fluctuations \(\varepsilon _\mathrm{S}\) for a given volume of size \(r\),

with \(\beta \approx 0.4\) being the Obukhov–Corrsin constant (Sreenivasan 1996). These dissipation rates, in turn, were modelled using the parametrization of SGS turbulence. According to the SGS scheme used in PALM, the local structure parameters for a given LES grid volume of size \(\varDelta (r=\varDelta )\) can be calculated by the so-called dissipation method and Eq. 2 then yields

where \(\varDelta = \root 3 \of {\varDelta _x \varDelta _y \varDelta _z}\) with \(\varDelta _x\), \( \varDelta _y\) and \(\varDelta _z\) being the grid resolutions of the Cartesian coordinate system \((x_1 = x,x_2 = y,x_3 = z)\). The SGS mixing length \(l\) depends on height and stratification; in unstable stratification \(l\) usually equals \(\varDelta \), whereas \(l\) becomes smaller in stably stratified regions (Deardorff 1980). For a detailed derivation and validation of both spectral and dissipation methods see Cheinet and Siebesma (2009) and Maronga et al. (2013b). The latter also showed that the spatial distribution of structure parameters derived from the dissipation method agree well with those from local turbulence spectra using a wavelet transform approach.

3.2 Monin–Obukhov Similarity Relationships

The derivation of the surface sensible and latent heat fluxes from scintillometer measurements is based on the application of MOST for the structure parameters of temperature and humidity (e.g. Andreas 1988). Following MOST, a given non-dimensional group of a turbulence quantity in the surface layer is a unique function of the stability parameter \(z/L\), with \(z\) being measurement height and \(L\) being Obukhov length, defined as \(L = - \left( \overline{\theta _\mathrm{v}}u_*^3\right) /\left( \kappa g \overline{w'\theta _\mathrm{v}'}_0\right) \) (Obukhov 1946). Here, \(u_*\) is the friction velocity, \(\theta _\mathrm{v}\) is virtual potential temperature, \(\kappa = 0.4\) is the von Kármán constant, \(g\) is the acceleration due to gravity, and \(\overline{w'\theta _\mathrm{v}'}_0\) is the near-surface buoyancy flux. \(C_T^2\) and \(C_q^2\) should thus satisfy

with \(\theta _* = -\overline{w'\theta '}_0/{u_*}\) and \(q_* = -\overline{w'q'}_0/{u_*}\); \(\overline{w'\theta '}_0\) and \(\overline{w'q'}_0\) are the kinematic surface fluxes of heat and moisture, respectively. If both \(C_T^2\) and \(C_q^2\) follow MOST, then \(f_T\) and \(f_q\) should be universal functions of \(z/L\). So far it has not been possible to derive a precise form for \(f_T\) and \(f_q\), but several empirical formulations have been proposed for unstable conditions from experimental data (Wyngaard et al. 1971b; Wesely 1976; Andreas 1988; Thiermann and Grassl 1992; Hill et al. 1992; De Bruin et al. 1993; Li et al. 2012). Most suggest the following form

with dimensionless constants \(c_{TT1}, c_{TT2}, c_{qq1}\) and \(c_{qq2}\) that are determined empirically and characterize the transition from near-neutral to free convective conditions (see also the discussion in Braam 2014). Hill (1989) pointed out that, if the structure parameters all follow MOST, their similarity functions must be the same (\(f_T = f_q\)), and temperature and humidity must be perfectly correlated (i.e. correlation coefficient \(R_{Tq} = 1\)). However, often it is found that \(R_{Tq} \ne 1\) (e.g. Beyrich et al. 2005) and it was shown by Li et al. (2012) and Maronga (2014) that \(f_T \ne f_q\) can be observed in such situations. The latter showed that \(C_T^2\) usually follows MOST, whereas \(C_q^2\) is often affected by entrainment of dry air at the top of the mixed layer and thus does not follow MOST.

When mechanical production is much less important than the buoyant generation of turbulence (e.g. when the wind speed is small and \(z/L\rightarrow -\infty \)) \(L\approx 0\) and no longer a proper scaling parameter. When buoyancy is the driving force the surface layer should behave as in free convection. In this case a special solution of MOST can be used, which is commonly referred to as local free convection (LFC) (e.g. Wyngaard et al. 1971a), and the dimensionless structure parameters are given by

with \(\theta _\mathrm{LF} = \overline{w'\theta '}_0/w_\mathrm{LF}\), \(\theta _\mathrm{LF} = \overline{w'\theta '}_0/w_\mathrm{LF}\) and \(w_\mathrm{LF} = \left( (g/\overline{\theta _\mathrm{v}}) \overline{w'\theta _\mathrm{v}'}_0 z\right) ^{1/3}\). Due to the limited parameters in LFC scaling there is only one dimensionless group and \(A_T\) and \(A_q\) should be universal constants (see Andreas 1991). Measurements suggest that \(A_T = 2.7\) (Wyngaard et al. 1971b; Kaimal et al. 1976; Wyngaard and LeMone 1980; Kunkel et al. 1981; Andreas 1991). While Wyngaard and LeMone (1980) suggested \(A_q \approx 1.5\), Andreas (1991) proposed that \(A_T = A_q = 2.7\) (when \(R_{Tq} = 1\)), referring to the study of Hill (1989). The previous LES study of Peltier and Wyngaard (1995) suggested \(A_q = 2.0-2.7\). However, these authors also showed that \(A_q\) can be higher than \(A_T\) due to entrainment effects. Maronga (2014) found that \(A_T = 2.7\) and explicitly showed that the value of \(A_q\) is not universal if the entrainment of dry air is significant (\(C_q^2\) does not follow MOST/LFC scaling), which can often be the case and may explain the range of values in the literature. Otherwise we take \(A_T \approx A_q\).

It can also be shown that LFC scaling is a limiting behaviour of MOST by using Eqs. 4–7; taking the free convection limit, i.e. \(-z/L \rightarrow \infty \) (De Bruin et al. 1995), it follows that

which gives a direct link between the universal parameters in MOST and LFC scaling.

3.3 LES Data Processing

\(C_T^2\) and \(C_q^2\) were derived from both the spectral and the dissipation methods (see Eqs. 1 and 3) as described in Maronga et al. (2013b). Cheinet and Siebesma (2009) and Maronga et al. (2013b) both found that the dissipation method yields structure parameters that are too small in magnitude (compared to semi-empirical profiles), whereas the spectral method gives reliable estimates of \(C_T^2\) and \(C_q^2\) in the study of Maronga et al. (2013b). The simulation data in the latter study, as well as the data in the present study, suggest a constant correction factor for the dissipation method of 1.7–1.9. In the present study we used the data from the spectral method to determine this correction factor, giving a value of 1.85 (evaluated at the height of the VLAS, see Appendix). We decided to use the corrected structure parameters from the dissipation method for our analysis, because it gives local estimates, which allows investigation of possible local effects of surface heterogeneity on the structure parameters and VLAS measurements.

Here, we use these VLAS data along the path from the GM site (transmitter) to the MOL site (receiver) (see Fig. 1b) for comparison with LAS data. We employed the dissipation method and calculated the path-weighted average of the structure parameters along horizontal paths in the LES model as suggested by Maronga et al. (2013b) (see their Fig. 6 and Appendix). They argued that, on the one hand, the scintillations seen by LAS are mainly determined by fluctuations at the scale of the aperture (here 0.15 m), whereas smaller scales are averaged out and larger scales lead to variability of the scintillations. On the other hand, the nominal truncation size (or nominal aperture of the VLAS) in the LES is \(\varDelta \approx 2.7\) m (the actual truncation happens at even larger scales up to \(6\varDelta \)), so that part of the variability in the structure parameters seen by the LAS is unresolved by the LES, and thus in the VLAS data.

3.4 Footprint Analysis

In our simulations, cyclic lateral boundary conditions were used, implying that the prescribed surface heterogeneity was repeated periodically. This does not occur in reality. In the vicinity of the horizontal domain boundaries the flow is hence exposed to an erroneous surface forcing. It is thus essential that a sufficiently large buffer zone is prescribed so that the VLAS signal is not affected by the cyclic boundary conditions. The surface area was chosen in such a way that the VLAS path was located close to the western boundary of the model. A footprint analysis for the VLAS path in the LITFASS area on May 30 2003 was conducted using the LES data as input for the analytical footprint model of Kormann and Meixner (2001), designed for a point source. We hence applied a convolution with the VLAS path-weighting function to obtain the LAS footprint as suggested by Meijninger et al. (2002b). As easterly winds were prescribed in the model, the footprint of the VLAS was located in the upstream direction; footprints for selected times are shown in Fig. 3. As expected the footprint source area was located in the area east of the path, with 90 % of the footprint lying within a distance of 200 m from the scintillometer path (see Fig. 1b). Only small variability of the footprints in time is observed that can be ascribed to the strongly convective character of the ABL. The fetch of 4 km was thus much larger than the required upstream domain according to the footprint analysis. Therefore, it is possible to compare VLAS measurements with the in situ LAS data obtained during LITFASS-2003. A typical contribution of the land use to the footprint was (e.g. at 1100 UTC): 56% triticale, 23% rape, 6% maize, 4% barley, 4% forest and 7% grassland. If no blending height exists below the VLAS, this composition suggests that the VLAS predominantly samples turbulence originating from triticale and rape. Figure 2a shows the flux averaged over the VLAS footprint area, derived from the weighted contribution of the individual land-use classes to the footprint area. It can be seen that the VLAS footprint is coincidentally in remarkable agreement with the area-averaged surface sensible heat flux used for case HOM throughout the day. A similar behaviour can be observed when considering the surface latent heat flux (see Fig. 2b).

4 Results

4.1 Mean Profiles

The horizontally-averaged (denoted by angular brackets) profiles of \(\theta \) and \(q\) are shown in Fig. 4a and b for both cases LIT2E and HOM, respectively. In the early morning (0500 UTC) the temperature and humidity profiles show a near-surface inversion up to a height of 150 m, a residual layer with slightly stable stratification above and a capping inversion starting at 850 m. At 0700 UTC the near-surface inversion begins to erode and the residual layer is incorporated into the developing mixed layer. During this so-called morning transition \(z_{i}\) rapidly increases from 200 to 1,000 m. At 1300 UTC \(z_{i}\) has increased to 1,500 m. Maronga and Raasch (2013a) found a mean \(z_{i}\) of 1,795 m for the entire LITFASS area, and showed that \(z_{i}\) was up to 15 % smaller over the farmland area due to the smaller heat input into the atmosphere over this surface (see their Fig. 7a). This explains the lower \(z_{i}\) in the present study.

The profiles of \(\langle \theta \rangle \) reveal a warming of the ABL with a maximum mixed-layer temperature close to 297 K at 1300 UTC; \(\langle q \rangle \) is characterized by a continuous decrease in time after 0700 UTC, reaching \(4\hbox { g kg}^{-1}\) at 1300 UTC. One important process relates to the entrainment of dry air at the top of the CBL, which decreases the CBL humidity. This is shown in Fig. 4f: the moisture flux at the top of the CBL is a factor of 3–4 higher than the respective surface flux all day long (entrainment flux ratio of 3–4), leading to a net moisture loss in the CBL. In contrast, the entrainment flux ratio is only around \(-0.2\) for the kinematic heat flux (see Fig. 4e), showing that the relative importance of the surface flux is high for sensible heat and low for latent heat. Moreover, the available water vapour is reduced as the CBL grows in the course of the day. As the sum of both processes is not balanced by the released water vapour at the surface, the CBL dries out in the course of the day. This is often observed in the CBL, was a frequent feature during LITFASS-2003, and was also previously shown by Couvreux et al. (2005, 2007). Both the profiles of \(\langle \theta \rangle \) and \(\langle q\rangle \) are comparable with the previous LES runs for the LITFASS area (see Maronga and Raasch 2013a). It can also be seen from Fig. 4a, b that the mean profiles, and in particular the height of the temperature inversion (and thus \(z_{i}\)), are not modified significantly by the surface heterogeneity. While Maronga and Raasch (2013a) showed that secondary circulations developed that spanned the entire domain and affected the horizontally-averaged \(z_{i}\), the surface heterogeneity in the present study does not show such effects, most likely due to the fact that the heterogeneity scales and amplitudes are rather small (compared to the amplitude between forest and water patches that led to strong secondary circulations in Maronga and Raasch (2013a)).

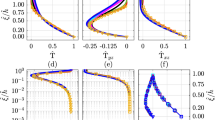

Figure 4c, d shows the mean profiles of \(C_T^2\) and \(C_q^2\), respectively. Both \(\langle C_T^2\rangle \) and \(\langle C_q^2\rangle \) display a maximum near the surface, caused by the generation of small-scale turbulence due to rising thermals and wind shear. \(\langle C_T^2\rangle \) decreases in the mixed layer up to levels where entrainment processes become important, leading to temperature fluctuations at the interface between the mixed layer and free atmosphere and thus a secondary peak in \(\langle C_T^2\rangle \). The shape of the \(\langle C_T^2\rangle \) profiles is in agreement with previous LES studies (Peltier and Wyngaard 1995; Cheinet and Siebesma 2009; Maronga et al. 2013b) and semi-empirical profiles after Kaimal et al. (1976). The shape of \(\langle C_q^2\rangle \) is in agreement with previous studies as well (Fairall 1987; Peltier and Wyngaard 1995; Cheinet and Cumin 2011; Maronga et al. 2013b). \(\langle C_q^2\rangle \) increases throughout the mixed layer, suggesting that fluctuations of humidity in the CBL are controlled by the entrainment of dry air at the top of the mixed layer. This is supported by the entrainment flux ratio of 3–4 (see Fig. 4f), and in agreement with observations (e.g. Druilhet et al. 1983). Secondary peaks of \(\langle C_T^2\rangle \) and \(\langle C_q^2\rangle \) that can be observed at 800 m (at 0700 UTC) can be ascribed to turbulent fluctuations at the top of the residual layer during the morning transition. Peaks for \(\langle C_q^2\rangle \) around 2000 m are caused by the humidity jump from 1,900–2,000 m. For both \(\langle C_T^2\rangle \) and \(\langle C_q^2\rangle \) some differences between cases LIT2E and HOM are observed, even though they appear to be marginal, particularly for \(\langle C_T^2\rangle \). We consider whether these differences affect the structure parameters at the height of a LAS system, and the similarity relationships, in the following Sect. 4.2.

4.2 Monin–Obkuhov Similarity Relationships

The mean profiles of \(C_T^2\) and \(C_q^2\) in the lowest 150 m reveal that both \(\langle C_T^2\rangle \) and \(\langle C_q^2\rangle \) are higher in case LIT2E than in case HOM (not shown); on average the difference is 4.2 and 12.0 % for \(C_T^2\) and \(C_q^2\), respectively. This difference might affect the MOST and LFC constants for \(C_T^2\) and \(C_q^2\). Due to the non-linear relationships between structure parameters and surface fluxes (Eq. 4–5, 8–9), the percentage error in the surface fluxes is, however, smaller than for the structure parameters. We can thus conclude that the MOST relationships can only be slightly modified. The dimensionless structure parameters have been calculated for all \(z \le \) 150 m every 10 s according to Eqs. 4 and 5, with results shown in Fig. 5. It is visible in Fig. 5a that the data points of the dimensionless \(\langle C_T^2 \rangle \) differ slightly between cases LIT2E and HOM, which can be related to the differences in \(\langle C_T^2\rangle \) discussed above. Moreover, Fig. 5a shows that all data points are in good agreement with the similarity function \(f_T\) proposed by Maronga (2014). The range of the stability parameter \(-z/L\), which varies due to differences in \(z\) as well as due to changes in the surface fluxes in the diurnal cycle, covers values from 10 to 200, so that LFC scaling is an appropriate choice. We hence later derive the LFC constants. Since the stability range is limited to nearly free convective conditions, it is not possible to derive representative fitting functions \(f_T\) (and hence values for \(c_{TT1}\) and \(c_{TT2}\)) from the present dataset. Much more data points for conditions with higher geostrophic winds and lower surface fluxes would be required in order to cover the whole stability range from free convective down to near-neutral conditions with \(-z/L \approx 0.01\) (see e.g. Li et al. 2012). Nevertheless, we can derive the function \(f_T\) from this dataset. For \(c_{TT1}\), which represents the behaviour in the neutral limit, it is reasonable to use the proposed value of \(6.1\) after Maronga (2014), while \(c_{TT2}\) is chosen to best fit the data in the present study. The LES data suggest

and

and from these values of \(c_{TT1}\) and \(c_{TT2}\) it follows that \(A_{T,\mathrm{LIT2E}} = 3.0\) and \(A_{T,\mathrm{HOM}} = 2.8\). This difference between \(A_{T,\mathrm{LIT2E}}\) and \(A_{T,\mathrm{HOM}}\), though relatively small, indicates that the MOST functions over heterogeneous terrain indeed differ slightly from those over homogeneous terrain. However, heterogeneity effects are less prominent for near-neutral conditions since surface heterogeneity signals are known to be weakened for increasing wind speed or smaller surface fluxes (e.g. Avissar and Schmidt 1998). The largest effect of surface heterogeneity on the MOST relationships will be present in free convection, a finding based only on one single case study with a certain surface heterogeneity and amplitude. Moreover, the difference in \(A_T\) appears to be rather small (\(0.2\)) so that we cannot infer whether such a deviation exists for any given heterogeneous terrain. We revisit this question later and hereafter use the formulations for \(f_T\), \(f_q\) after Maronga (2014).

Dimensionless structure parameters (MOST scaling) against stability parameter \(-z/L\). a Shows data for \(C_T^2\), and b shows data for \(C_q^2\). The data are complemented by the LES fitting function \(f_T\) and \(f_q\) (solid black lines) after Maronga (2014)

Figure 5b shows that the dimensionless \(\langle C_q^2 \rangle \) does not collapse onto a single curve and it is evident that the data do not agree with the proposed function \(f_q\), and that there are only a few data points that can be considered to follow MOST. These are located very close to the surface (not shown). It is also obvious that no fitting function can be derived from the present data, and we must conclude that \(C_q^2\) generally does not follow MOST in the present study. This finding can be again attributed to the fact that the ratio of the entrainment flux to the surface flux of latent heat, for case LIT2E was around 3–4 (see Fig. 4f). As was shown by Maronga (2014), \(C_q^2\) no longer follows MOST if this ratio \(>\)1. The entrainment of dry air is then the dominant process that affects \(C_q^2\) in the surface layer, in agreement with the assumption of Li et al. (2012). The present study supports this finding so that it is impossible to derive a value for \(A_q\). As a direct consequence, MWS measurements should not be used to derive the surface flux of latent heat when the entrainment of dry air becomes too large.

The vertical profiles of \(\langle C_T^2 \rangle \) and LFC predictions according to Eqs. 8–9 are shown in Fig. 6 and reveal \(A_{T,\mathrm{LIT2E}} = 3.0\pm 0.2\) and \(A_{T,\mathrm{HOM}} = 2.8\pm 0.2\) (95 % confidence interval), which is in agreement with the predictions of MOST scaling in the free convection limit as shown above. These values are slightly higher than the value of 2.7 reported from measurements (e.g. Wyngaard et al. 1971b; Wyngaard and LeMone 1980; Andreas 1991) and also from the recent LES study of Maronga (2014). For case HOM the difference is only small (0.1) and within the confidence interval (\(\pm \)0.2); we attribute this difference to the fact that perfect free convective conditions are not reached in our LES runs. The difference between cases LIT2E and HOM, even though also small (0.2), is most likely related to surface heterogeneity effects. We hereafter use the value of \(A_T = 2.7\), which was derived for free convective conditions by Maronga (2014) and discuss the errors induced by the surface heterogeneity and implications for LAS observations over heterogeneous terrain in Sect. 4.4.

4.3 Blending Height

MOST theoretically is only applied to derive surface fluxes from elevated LAS measurements if a blending height for structure parameters lies somewhere below the scintillometer path. Otherwise, the scintillometer “sees” the fluxes from different surface patches and a footprint analysis must be employed to relate the LAS signal to the surface fluxes of the different surface types (Meijninger et al. 2002b, 2006; Beyrich et al. 2012). Furthermore, in the latter case, MOST is violated, and likely will introduce additional errors. Then, the derived surface fluxes can at best be regarded only as representative for the footprint area. The spatial distribution of surface types and thus surface fluxes within this footprint area, however, might be completely different from the area-averaged fluxes at a larger scale.

Sühring and Raasch (2013) introduced a method to determine the blending height in the case of heterogeneous surface heating for two days of the LITFASS-2003 experiment including LIT2E. They particularly found that high correlation between the surface-flux pattern and the pattern of the turbulent fluxes in the ABL can still be seen even in the entrainment zone. We used their method, which is based on the method described by Lohou et al. (1998, 2000), and calculated the two-dimensional cross-correlation \(\rho \) between the time-averaged spatial surface heat-flux pattern and the time-averaged horizontal pattern of the structure parameters against different spatial lags in \(x\)- and \(y\)-directions at different heights. Here, \(\rho \) is defined as

with \(\rho _{\overline{w'S'}_0,\overline{C_S^2}}(\delta x, \delta y, z) \in \left[ -1,1\right] \), \(\delta x\) and \(\delta y\) are the spatial displacement lengths between \(\overline{w'S'}_0\) and \(\overline{C_S^2}\) and multiples of \(\varDelta _x\) and \(\varDelta _y\), respectively. The tilde indicates a deviation from the horizontal mean, while \(L_x = L_y = 5.3\hbox { km}\) are the lateral bounds of the model domain. The temporal average (indicated by the overbar) over an interval of 30 min is used to remove noise from the randomly-distributed turbulence so that spatial variations in either the surface heat flux or the structure parameter must be exclusively related to effects of the surface heterogeneity. The application of this method is strictly limited to cases with surface heterogeneity because \(\overline{w'S'}_0 = 0\) over a homogeneous surface and the correlation coefficient is then not defined. For a detailed description of this method, see Sühring and Raasch (2013).

Exemplarily, Fig. 7 shows the horizontal cross-sections of \(\overline{C_T^2}\) and \(\overline{C_q^2}\) at the VLAS height (43 m) at 1100 UTC for case LIT2E. It is obvious that a heterogeneity-induced signal is still visible for both \(\overline{C_T^2}\) and \(\overline{C_q^2}\) at the height of the VLAS, particularly from the patches with the highest surface fluxes of sensible and latent heat, respectively. This was mainly forest with a surface sensible heat flux \(\approx \) 470 W m\(^{-2}\) (see Fig. 2a) and rape crop with a surface latent heat flux \(\approx \) 170 W m\(^{-2}\) (see Fig. 2b). Comparing Fig. 7 with the land-use cover (see Fig. 1b) reveals that forest and rape patches can be easily identified in the horizontal cross-sections of \(\overline{C_T^2}\) and \(\overline{C_q^2}\), respectively. Horizontal homogeneity of turbulence can thus not be assumed, at least at the VLAS height at 1100 UTC. This is supported by the correlation coefficients between \(\overline{w'\theta '}_0\) and \(\overline{C_T^2}\) (denoted as \(\rho _{\overline{w'\theta '}_0,\overline{C_T^2}}\)) as well as between \(\overline{w'q'}_0\) and \(\overline{C_q^2}\) (denoted as \(\rho _{\overline{w'q'}_0\overline{C_q^2}}\)). Figure 8 shows \(\rho _{\overline{w'\theta '}_0,\overline{C_T^2}}\) and \(\rho _{\overline{w'q'}_0,\overline{C_q^2}}\) versus the spatial lag in the \(x\)- and \(y\)- directions for three levels. Close to the surface the maximum correlation has values close to \(1\) and a spatial lag of zero (Fig. 8a,d). On the one hand, the maximum correlation has decreased to 0.65 for \(\rho _{\overline{w'\theta '}_0,\overline{C_T^2}}\) at a height of 43 m (VLAS) and it is shifted downstream (in \(x\)-direction) to \(x = -25\) m. At 200-m height, the maximum correlation has decreased to \(0.3\) and moved further downstream to \(x = -150\) m. This vertical skewing of the maximum correlation can be ascribed to the boundary-layer flow, which advects the heterogeneity signal along the mean wind direction. On the other hand, the maximum correlation of \(\rho _{\overline{w'q'}_0,\overline{C_q^2}}\) has decreased drastically to 0.3 at a height of 43 m, and at \(z=200\) m it has further decreased to \(\approx {\pm }0.2\).

Based on this finding we calculated the vertical profiles of the maximum correlation in each horizontal plane (denoted as \((\rho )_{\max }\)) for each hour of simulation time. The results are shown in Fig. 9. The maximum \(\rho _{\overline{w'\theta '}_0,\overline{C_T^2}}\) reveals that, close to the surface, the \(C_T^2\) signal is highly correlated to \(\overline{w'\theta '}_0\), but that the correlation decreases with height down to values between 0.2 and 0.3 at heights 200–600 m (valid for the whole simulated time period). The maximum \(\rho _{\overline{w'q'}_0,\overline{C_q^2}}\) rapidly decreases in the lowest 100 m, presumably due to the entrainment of dry air that affects the humidity fluctuations in the surface layer, but which does not affect \(C_T^2\) and the surface fluxes. Both maxima \(\rho _{\overline{w'\theta '}_0,\overline{C_T^2}}\) and \(\rho _{\overline{w'q'}_0,\overline{C_q^2}}\) show no secondary peak near the entrainment zone, which suggests that heterogeneity signals of the structure parameters do not expand into the upper mixed layer. Sühring and Raasch (2013) found that, even though the correlation between the surface sensible heat flux and the heat flux in the mixed layer was low, a high anti-correlation could be observed in the entrainment zone. From the low correlation in the mixed layer found in the present study we can thus not prove that a blending height exists for structure parameters. The remarkable high maximum correlation coefficient in the lowest 100–200 m with values \(\ge \)0.5 suggests that a blending height must be located considerably higher than the LAS system installed at 43 m during the LITFASS-2003 experiment (Beyrich and Mengelkamp 2006). If the observed high correlation is not case specific for moderately heterogeneous surfaces, our results apply for all common LAS systems that are usually installed at heights \(<\)70 m (e.g. Kohsiek et al. 2002; Meijninger et al. 2002b; Beyrich et al. 2012). In order to prove that heterogeneity signals have to be considered in LAS observations, \(\rho _{\max }\) is shown in Fig. 10 at the VLAS height during the course of the day. It is obvious that the correlation between \(\overline{w'\theta '}_0\) and \(\overline{C_T^2}\) is constant around 0.7. Signals from the surface heterogeneity will hence be visible in the VLAS signal throughout the day. For \(\overline{C_q^2}\) the correlation is generally smaller and shows maximum values around 0.6. We attribute this to the effect of the high entrainment flux ratio of 3–4 for latent heat throughout the simulation so that the surface layer is significantly affected by entrained dry air. However, our analysis shows that signals of the surface heterogeneity pattern are still visible at the VLAS height, but that MOST is no longer applicable for \(C_q^2\). Between 0700 UTC and 0900 UTC the correlation decreases down to values of 0.2 (Fig. 10). We attribute this to the fact that the surface signal does not reach the VLAS height when vigorous entrainment events, such as the eroding residual layer during the morning transition (see Sect. 4.1), penetrate deep into the surface layer. Under such conditions \(C_q^2\) is decoupled from \(\overline{w'q'}_0\) even at low levels, and we show later that this time period coincides with maximum values of \(C_q^2\) caused by entrained dry air. This analysis is, of course, only based on part of the diurnal cycle for a specific day with a specific surface heterogeneity pattern, but we can already say that a blending height, if existing at all, is often located much higher than the level of usual LAS measurements. Heterogeneity signals thus affect LAS measurements and have to be considered in the interpretation of the data.

4.4 Spatial and Temporal Variability of Structure Parameters and VLAS Measurements

In Sects. 4.1 and 4.3 we showed that surface heterogeneity affects the local structure parameters and their similarity relationships. Here we discuss the impact on LAS measurements. Figure 11 shows the time series of \(\langle C_T^2\rangle \) and \(\langle C_q^2\rangle \) at the VLAS (43 m) height. It appears that \(\langle C_T^2\rangle \) reflects the evolution of \(\langle \overline{w'\theta '}_0\rangle \) very well (cf. Fig. 2a), and it is plausible to consider MOST as an appropriate framework to derive the surface sensible heat flux from measurements of \(C_T^2\). Moreover, it is also clear that the value of \(\langle C_T^2\rangle \) is slightly higher for case LIT2E than for case HOM, suggesting that the surface heterogeneity generates additional temperature fluctuations that lead to a higher \(\langle C_T^2\rangle \).

In contrast, \(\langle C_q^2\rangle \) does not back up the temporal development of \(\langle \overline{w'q'}_0\rangle \) in the course of the day (cf. Fig. 2b). A strong peak is visible at 0700 UTC that cannot be related to any release event of moisture at the surface. From a comparison with the temporal development of the CBL height (see also Fig. 4a) it becomes evident that this peak is related to the erosion of the morning inversion and the subsequent inclusion of the residual layer into the mixed layer, causing strong and rapid entrainment. The second peak around 0800 UTC is also related to an entrainment event (cf. Fig. 10), consistent with results discussed in Sect. 4.3. Effects of surface heterogeneity on \(\langle C_q^2\rangle \) are hence not prominent from 0700 UTC to 0900 UTC, because entrainment processes are not correlated to the surface heterogeneity pattern.

Time series of the maximum values of the correlation coefficient in the horizontal cross-section at a height of 43 m between \(\overline{w'\theta '}_0\) and \(\overline{C_T^2}\) (solid line) and \(\overline{w'q'}_0\) and \(\overline{C_q^2}\) (dashed line). The data was averaged in time over an interval of 30 min

In order to quantify how surface heterogeneity affects LAS observations, we now investigate the temporal variability of VLAS observations (a weighted VLAS path-average is thus denoted by \([C_T^2]\)) and the variability of \(C_T^2\) along the VLAS path. As was shown in Fig. 7, surface heterogeneity effects are visible in the temporally-averaged data at the VLAS height. Figure 12a shows the time series of \([C_T^2]\), obtained every 10 s, together with the temporally-averaged VLAS measurements \(\overline{[C_T^2]}\), the horizontally and temporally-averaged data \(\overline{\langle C_T^2\rangle }\) and the LAS observations during the LITFASS-2003 experiment (denoted by \(\overline{[C_T^2]}_\mathrm{LAS}\)). The instantaneous \([C_T^2]\) varies rapidly in time due to the turbulence along the measurement path; in the morning these fluctuations are rather small because turbulence intensity is low, but in the course of the day, the turbulence intensifies and hence also the fluctuations in the VLAS signal increase. Case HOM shows a very similar behaviour of the instantaneous VLAS signal (Fig. 12b). Now we applied a temporal average over 30 min to the VLAS observations, which was the same averaging interval as used for the analysis of the LAS data. The choice of this interval is also confirmed by the study of Maronga et al. (2013b) (see their Fig. 11). The averaged data reveal that \(\overline{[C_T^2]}\) converges to the horizontal average \(\overline{\langle C_T^2\rangle }\) fairly well, and a promising result regarding the determination of the area-averaged fluxes from the VLAS observations. However, average differences between \(\overline{[C_T^2]}\) and \(\overline{\langle C_T^2\rangle } \approx 5\) % persist. Figure 12b gives evidence that this difference is due to the surface heterogeneity as no such difference can be observed in case HOM. Here, \(\overline{[C_T^2]}\) is in excellent agreement with \(\overline{\langle C_T^2\rangle }\).

Time series of \(C_T^2\) derived from VLAS measurements for the (a) heterogeneous, and (b) homogeneous cases. Shown are the instantaneous VLAS signal (grey solid line), collected every 10 s, in comparison with the 30-min average (blue line) and the horizontal average of \(C_T^2\) (red line) as well as the LAS observations (dark green). Additional time series of both the VLAS measurement (light green) and the horizontal average of \(C_T^2\) (black line) are given for case LIT2E_W (denoted as (W)). Due to a data loss the first 2 h (low flux values) are missing for LIT2E_W

Note that this good agreement between the VLAS measurement and the area-averaged \(C_T^2\) over heterogeneous terrain is no universal feature, because it is based on one single case study, and we suppose that this is due to the fact that the footprint of the VLAS is coincidentally representative of the entire area as shown in Sect. 3.4 (see Fig. 2a). In order to prove this, we employed case LIT2E_W, where the model domain was shifted in a westward direction so that a large patch of forest is captured by the model. The slightly different surface heterogeneity in case LIT2E_W leads to a significantly higher area-averaged surface sensible heat flux. If our hypothesis holds that the VLAS is rather representative for its footprint area, then the VLAS measurement should be comparable to that in case LIT2E because the footprint area does not change and is located over the farmland area to the east of the VLAS path (see also Meijninger et al. 2006). In case LIT2E_W, however, \(\langle C_T^2\rangle \) should deviate significantly from case LIT2E as the surface heterogeneity distribution and thus the area-averaged surface flux has changed. Figure 12a shows \(\overline{\langle C_T^2\rangle }\) as well as \(\overline{[C_T^2]}\) for both cases LIT2E and LIT2E_W, and it is obvious that \(\overline{\langle C_T^2\rangle }\) is indeed significantly higher in case LIT2E_W, as a result of the increased area-averaged surface sensible heat flux. By the same token it is clear that \(\overline{[C_T^2]}\) shows comparable values for both cases, which clearly supports our hypothesis.

The comparison of \(\overline{[C_T^2]}\) with \(\overline{[C_T^2]}_\mathrm{LAS}\) shows that the expected increase of \(C_T^2\) in the course of the day is captured by the LES (see Fig. 12a). Nevertheless it is also clear that \(\overline{[C_T^2]}_\mathrm{LAS}\) is about a factor of two lower than the \(C_T^2\) derived from the LES. The surface flux derived from the LAS (using MOST, not shown) was around \(200\hbox { W m}^{-2}\) around noon, whereas the prescribed area-averaged flux in the LES was close to \(250\hbox { W m}^{-2}\) (see Fig. 2a). Meijninger et al. (2006) showed that the LAS data generally compare well with the aggregated fluxes based on several eddy-covariance stations. This discrepancy between LES results and LAS measurements is to a large part a direct consequence of inappropriate flux forcing data, as discussed in Sect. 2. The fluxes used in the present study are thus about 50 W m\(^{-2}\) too high. The difference between the area-averaged surface fluxes used in our LES and the composite fluxes were found to account for 70 % of the difference between VLAS and LAS data.

In order to explore whether time-averaging is an appropriate procedure to quantify surface heterogeneity signal along the VLAS, and possibly to relate the local structure parameters to the local surface fluxes, different time-averaging intervals have been applied to the LES data. Figure 13 shows the variability of \(C_T^2\) along the VLAS path exemplarily at 1100 UTC for the instantaneous data as well as for the time-averaged data for averaging intervals of 30, 60 and 120 min. The plots are complemented by the underlying prescribed surface fluxes and the local fluxes that have been derived from MOST and \(f_T\) as hitherto used. This is a reasonable approach as the VLAS footprints (see Sect. 3.4) revealed that the VLAS mainly “sees” the heterogeneous surface below its path and slightly upstream. It is clear that the instantaneous signal cannot be related to the surface fluxes and that sufficient averaging is essential (Fig. 13a). The averaging interval, however, is limited due to changing surface fluxes and the state of turbulence in the diurnal cycle. Figure 13b shows that the surface heterogeneity is indeed visible in the time-averaged \(C_T^2\) (30-min average). The local surface fluxes derived from MOST give reasonable values, particularly in the vicinity of strongly-heated patches such as the forest at the beginning of the path and at around 1.5 km (cf. Figs. 7 and 1b). The comparison of the standard deviation of \(C_T^2\) along the VLAS path between cases LIT2E and HOM (0.0135 and 0.0068 K m\(^{-2/3}\), respectively, see Table 1) indicates that half of the variability along the path in case LIT2E is still caused by random noise due to turbulence. It is thus difficult for in situ measurements (such as low-level aircraft flights) to identify the surface heterogeneity that is a priori unknown. Table 1, Fig. 13c, d show that a longer averaging interval (60 and 120 min, respectively) does not improve the statistics. The contrary is the case. The signal from the surface heterogeneity weakens as the surface fluxes change during the diurnal cycle, but half of the variability is still caused by random noise. The assumption of van den Kroonenberg et al. (2012), that a surface heterogeneity signal can be detected by means of an ensemble of aircraft flights at different times and on different days should therefore be judged with caution.

\(C_T^2\) (top graphs of each plot) along the VLAS path at 1100 UTC for case LIT2E (black solid lines) in comparison with case HOM (blue solid lines). a shows the instantaneous signal, whereas b, c and d show time-averaged data with averaging intervals as indicated in the top right corner of the plot. The underlying surface sensible heat fluxes for case LIT2E and case HOM (red solid line and green dashed line, respectively) as well as MOST predictions using the \(C_T^2\) data (shown in the top graphs) are given in the bottom graphs of each plot. Path-averages and standard deviations are given in Table 1

Our results demonstrate not only that the VLAS measurements are made well below the blending height (if this exists at all), but also that signals from the local surface fluxes can be seen in the VLAS signal if an adequate time average (here 30 min) is applied. The local fluxes that have been derived by MOST are then in fairly good agreement with the prescribed surface values. Hence we conclude that MOST can also be a useful framework for deriving local surface fluxes from elevated LAS measurements.

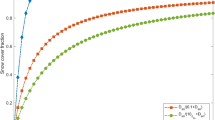

A direct comparison between the time-averaged surface fluxes (averaging interval of 30 min) derived from the VLAS observations using MOST and LFC scaling (denoted by \(\overline{[H]}_\mathrm{MOST}\) and \(\overline{[H]}_\mathrm{LFC}\), respectively) and the respective prescribed fluxes at the surface is given in Fig. 14. For \(f_T\) and \(A_T\) we applied the hitherto used formulations. It is clear from Fig. 14b that for case HOM, \(\overline{[H]}_\mathrm{MOST}\) is in remarkable agreement with the prescribed values at the surface with a relative error of only 1.2 %. This result shows that the derived MOST function for \(C_T^2\) does apply for a diurnal cycle as well, where the CBL is in a quasi-stationary state for no longer than 30 min. For \(\overline{[H]}_\mathrm{LFC}\) a slight overestimation for surface fluxes \(>\)120 W m\(^{-2}\) is visible such that the relative error is 4 % (Fig. 14d). This can be ascribed to the fact that pure local free convection is not present (due to the geostrophic wind speed of 2 m s\(^{-1}\)) and that LFC scaling is an over-idealization of the surface-layer structure (Hill 1989). Figure 14a, c suggests that the VLAS observations compare well with the area-averaged surface fluxes. However, higher deviations of 3 and 5.5 % for MOST and LFC scaling have to be considered, respectively. This is 1.5 % higher for both MOST and LFC scaling compared to case HOM and must be due to the surface heterogeneity. Moreover, it is evident that the VLAS-derived fluxes for case LIT2E tend to overestimate the prescribed surface fluxes, particularly when \(\overline{\langle H\rangle } > 150\) W m\(^{-2}\), which also explains the remaining difference of 15 W m\(^{2}\) between VLAS- and LAS-derived fluxes discussed above. This is in agreement with Lagouarde et al. (2002), Meijninger et al. (2002b) and Meijninger et al. (2006) who showed that the non-linearity between structure parameters and surface fluxes (see Sect. 4.2) leads to a systematic overestimation of the LAS-derived fluxes over heterogeneous terrain.

Surface flux of sensible heat derived from the time-averaged (30 min) VLAS measurements (denoted as \(\overline{[H]}\)) against the prescribed values at the surface (horizontal average, \(\overline{\langle H \rangle }\)). a shows the data points and regression lines using MOST scaling for cases LIT2E (plus signs, red line) and LIT2E_W (circles, blue line), b using MOST scaling for case HOM, c using LFC scaling for cases LIT2E and LIT2E_W and d using LFC scaling for case HOM. Due to a data loss the first 2 h are missing for LIT2E_W. The relative error of the VLAS measurement in relation to \(\overline{\langle H\rangle }\) is listed in each frame

As discussed above, the good agreement between VLAS measurements and area-averaged \(C_T^2\) is a fortunate coincidence to be ascribed to the fact that the heterogeneity in the footprint area is representative for the entire model domain (see Fig. 2a). This should be also considered when comparing the derived surface fluxes from the VLAS measurements. A comparison of the VLAS measurements from case LIT2E_W (see Fig.14a,c) reveals that for MOST the surface flux is slightly underestimated in case LIT2E_W, which is consistent with the higher area-averaged surface flux in this case. This underestimation, however, only leads to a very small increase in the error of 0.2 %. For LFC scaling it can be observed that the error in the derived surface flux is significantly reduced in case LIT2E_W, compared to LIT2E, which is counterintuitive. However, as discussed above, \(\overline{[H]}_\mathrm{LFC}\) was generally found to overestimate \(\overline{\langle H \rangle }_\mathrm{LFC}\) for \(\overline{\langle H \rangle } > 120\) W m\(^{-2}\) (see Fig. 14d). The increased value of \(\overline{\langle H \rangle }_\mathrm{LFC}\) in case LIT2E_W thus decreases the relative error to 3 %. In conclusion, Fig. 14 shows that, even though the VLAS measurements give rather reliable estimates of the footprint-averaged surface fluxes, they are also good estimates for the area-averaged surface fluxes in the case of moderate heterogeneity, with deviations from the area-averaged surface sensible heat flux in the order of only 5 %.

5 Summary

A case study for May 30 2003 of the LITFASS-2003 experiment was conducted using a set of large-eddy simulations (LES) that allow surface-layer turbulence to be resolved. The CBL over the heterogeneous LITFASS terrain was simulated from the early morning until early afternoon using prescribed surface fluxes of sensible and latent heat derived from eddy-covariance measurements over the major land-use classes. The model domain used was 5.3 km \(\times \) 5.3 km in area and represents the farmland portion of the LITFASS area. The data were compared with a homogeneous control run using spatially-averaged surface fluxes. \(C_T^2\) and \(C_q^2\) were derived from the simulation data over heterogeneous terrain and compared to data from the homogeneous simulation as well as with LAS data collected during the LITFASS-2003 experiment. Particular attention was given to the spatial distribution of \(C_T^2\) and \(C_q^2\) in the surface layer and to the MOST/LFC relationships, relating the structure parameters to the surface sensible and latent heat fluxes, respectively.

We found for the heterogeneous simulation that, compared to the homogeneous simulation, the mean \(C_T^2\) and \(C_q^2\) in the surface layer are about 4 and 12 % higher, respectively, and we showed that this difference slightly modifies the MOST/LFC relationships for \(C_T^2\). However, it transpires that the induced error did not exceed 1.5 % for both MOST and LFC scaling and is thus very small. It was also discussed that the VLAS-derived fluxes tend to overestimate the prescribed surface fluxes due to the non-linear relationship between structure parameters and fluxes, in agreement with previous scintillometer studies (Lagouarde et al. 2002; Meijninger et al. 2002b, 2006). We found that no MOST/LFC relationship can be obtained for \(C_q^2\) from the LES data as the entrainment of dry air at the top of the mixed layer was the dominant process generating humidity fluctuations. These fluctuations, in turn, affect the surface-layer dynamics in such a way that the surface latent heat flux is largely decoupled from the distribution of \(C_q^2\) in both the heterogeneous and homogeneous simulations.

A two-dimensional correlation analysis was used in order to investigate the blending height concept for structure parameters, and we showed that the structure parameters at a height of a few tens of m exhibit significant signals of the prescribed surface heterogeneity all day long. This result was more pronounced for \(C_T^2\) since the entrainment of dry air affected the humidity fluctuations in the surface layer and thus decreased the correlation between the surface latent heat flux and \(C_q^2\). However, signals of the surface heterogeneity were also visible in the \(C_q^2\) pattern. Consequently, horizontal homogeneity of turbulence as required by MOST cannot generally be expected, at least under highly convective conditions. As a result we conclude that, under such conditions, LAS observations are not representative of an area of several km\(^{2}\) (in the order of NWP grid boxes, e.g. 100 km\(^2\)), but only for their footprint area of very limited size (here in the order of 1 km\(^2\)). As this footprint might be composed of different surface patches with differing surface properties, the obtained surface flux from an LAS system does not necessarily have to be representative of a larger area. Our results are, of course, based on a single case where the LAS footprint was much smaller than would be the case for synoptic conditions with higher geostrophic winds and lower buoyant forcing at the surface. For the simulated case the area-averaged surface flux was in remarkable agreement with the footprint-integrated surface flux.

Simulated VLAS measurements in the LES runs were performed along a 4.8-km long path, in agreement with the LAS set-up during LITFASS-2003. A direct comparison showed that the VLAS measurements did overestimate the path-weighted \(C_T^2\) as observed by the LAS. A revision of the prescribed surface-flux data revealed that the flux forcing data used previously in several LES studies for the LITFASS-2003 experiment were too high in comparison with the processed composite eddy-covariance data from all available energy balance stations given in Beyrich et al. (2006). However, we believe this basically affects the direct evaluation of VLAS with the LAS, while all generalized results from this and former studies remain valid.

Moreover, we employed the VLAS measurements in order to investigate the effect of surface heterogeneity on LAS observations. It was found that sufficient time-averaging (here 39 min) is required to obtain representative fluxes and that signals of the underlying surface heterogeneity affect the VLAS observations. Whereas the VLAS measurement converged to the area-averaged value over homogeneous terrain, the VLAS observations in the heterogeneous simulation were found to retain a rather local character and showed a mean deviation of 5 % from the area average. This was confirmed by a sensitivity simulation with a different surface heterogeneity distribution. Due to the fact that the surface fluxes changed in the course of the day, such that stationary conditions were not reached in the simulation, the averaging interval was limited to 30 min. Therefore, 50 % of the variability of \(C_T^2\) along the VLAS path was caused by the remaining noise from random turbulent fluctuations and not related to surface heterogeneity. This shows that it is difficult for in situ measurements, such as low-level aircraft flights, to capture and quantify effects of the surface heterogeneity in the \(C_T^2\) signal.

Even though the blending-height analysis clearly suggested that the VLAS measurements cannot be considered to yield representative estimates of the area-averaged surface sensible heat flux, it would be necessary to perform a more sophisticated footprint analysis for the LES to confirm that the VLAS “sees” only the surface fluxes in its footprint area. In a future study we will employ a Lagrangian footprint model, embedded into the LES (see Steinfeld et al. 2008), over the heterogeneous LITFASS-2003 terrain in order to determine more elaborate footprints that take into account the surface heterogeneity.

Notes

Abbr. “Coordinated Information on the European Environment”, published by the European Environment Agency (http://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/COR0-landcover).

References

Andreas EL (1988) Estimating \(C_n^2\) over snow and sea ice from meteorological data. J Opt Soc Am 5:481–495

Andreas EL (1991) Using scintillation at two wavelengths to measure path-averaged heat fluxes in free convection. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 54:167–182