Abstract

Rhodopsin 7 (Rh7), a new invertebrate Rhodopsin gene, was discovered in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster in 2000 and thought to encode for a functional Rhodopsin protein. Indeed, Rh7 exhibits most hallmarks of the known Rhodopsins, except for the G-protein-activating QAKK motif in the third cytoplasmic loop that is absent in Rh7. Here, we show that Rh7 can partially substitute Rh1 in the outer receptor cells (R1–6) for rhabdomere maintenance, but that it cannot activate the phototransduction cascade in these cells. This speaks against a role of Rh7 as photopigment in R1–6, but does not exclude that it works in the inner photoreceptor cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vision begins with the absorption of photons by visual pigment molecules. Rhodopsins are membrane-bound G-protein-coupled receptors that absorb photons, undergo conformational changes, and activate a G-protein to initiate visual signal transduction. Animal genomes typically contain multiple Rhodopsin genes coding for Rhodopsins with different spectral properties providing the basis for color vision. Each photoreceptor cell usually expresses a single rhodopsin, but exceptions are known in both vertebrates and invertebrates (Applebury et al. 2000; Hu et al. 2011, 2014; Mazzoni et al. 2004; Stavenga and Arikawa 2008). The fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster possesses six different well-characterized Rhodopsin molecules, Rh1 to Rh6. With the exception of Rh2, all Rhodopsins are found in the receptor cells of the compound eyes: Rh1 is expressed in the six outer receptor cells (R1–6) of each eye unit and Rh3 to Rh6 are expressed in the two inner receptor cells (R7, R8) (reviewed in Rister et al. 2013; Behnia and Desplan 2015). A seventh Rhodopsin, Rh7, of still unknown location and function was predicted from the genome in 2000 (Adams et al. 2000; Terakita 2005). qPCR studies showed that Rh7 is expressed at low levels in the compound eyes, suggesting that it may be co-expressed with one or several of the other Rhodopsins (Posnien et al. 2012; Senthilan and Helfrich-Förster 2016).

The aim of the present study was to investigate a potential function of Rh7 in the compound eyes. A suited method to reveal the properties of an unknown Rhodopsin is to express it in R1–6 instead of Rh1 (Feiler et al. 1988; 1992; Townson et al. 1998; Salcedo et al. 1999; Knox et al. 2003; Hu et al. 2014). Rh1 is required for proper rhabdomere morphogenesis and maintenance, in addition to its role as photopigment (O’Tousa et al. 1985; Kumar and Ready 1995; Kumar et al. 1997; Zuker et al. 1985). Thus, loss of Rh1 (in ninaE 17 mutants) leads to the collapse of rhabdomeric microvilli inside the photoreceptor cytoplasm (Ahmad et al. 2007; Bentrop 1998; Kurada and O’Tousa 1995; Leonard et al. 1992). This can be prevented by expressing other functional Rhodopsins in R1–6 of ninaE 17 mutants (Kumar et al. 1997). Here, we expressed Rh7 instead of Rh1 under the Rh1 promotor (Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 flies) and investigated whether Rh7 can (1) rescue the retinal degradation provoked by the ninaE 17 mutation and (2) lead to normal electroretinogram (ERG) responses. We also expressed Rh7 in addition to Rh1 (Rh1–Rh7 flies) to see whether this increases the ERG responses.

Materials and methods

Fly strains

Wild-type CantonS (WTCS) as well as flies with yellow body color and white eyes (yellow− white 1118 = y − w 1118) served as control for semi-thin sections and immunocytochemistry. For qPCR, deep pseudopupil, and ERG measurements, only flies in the y − w 1118 background were used. In addition, ninaE 17 and sev LY3 mutants were in the y − w 1118 background. ninaE (=neither inactivation nor afterpotential E) codes for Rh1 and y − w 1118 ; ninaE 17 mutants are Rh1 null mutants (O’Tousa et al. 1985). sev (sevenless) codes for a tyrosin kinase that is critical for the development of the photoreceptor cell R7 (Basler and Hafen 1988) and y − w 1118 sev LY3 mutants lack the inner photoreceptor cell R7 (Harris et al. 1976). In the following, we will omit “y − w 1118” and simply use ninaE 17 and sev LY3.

Generation of Rh1–Rh7 transgenic flies

To generate flies expressing the Rh7 coding region under control of the Rh1 promotor, the full-length Rh7 CDS was amplified by PCR from a commercially available cDNA clone, GH14208 (Berkley Drosophila Genome Project), using a primer pair creating restriction enzyme sites for EcoRI or NotI, respectively. The digested PCR product was first ligated into vector pBRh1UTR providing an Rh1 minimal promoter and the Rh1–3′UTR (kind gift of A. Huber, Universität Hohenheim). From this vector, a NotI/XhoI-fragment containing Rh1 promotor + Rh7 coding sequence + Rh1 3′-UTR was excised and ligated into the P-element vector Yellow-C4 (P. Geyer, University of Iowa). To create transgenic fly lines, the construct was then microinjected into y − w 1118 embryos resulting in several insertion lines. The insertion lines were tested for Rh7 expression by qPCR. One line with the transgene insertion on the second chromosome (y − w 1118 ;Rh1–Rh7;+) yielded the highest Rh7 expression and was subsequently used for all experiments. This line was crossed into the ninaE 17 mutant background (y − w 1118 ;Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 ) to get flies that express Rh7 instead of Rh1. Furthermore, the y − w 1118 ;Rh1–Rh7;+ line was backcrossed into the y − w 1118 background for several generations (=backcross) to get control flies with the same genetic background as the transgenics. In the following, we will simply call the lines Rh1–Rh7, Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17, and backcross. We checked the presence of all Rhodopsins by qPCR and did not find any differences to wild-type flies.

PCR

DNA of single flies was extracted in Squishing Buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl pH8.2, 1 mM EDTA, 25 mM NaCl with 2 mg Proteinase K per ml) by incubating for 30 min at 56 °C. After inactivation of the Proteinase K by incubation at 93 °C for 3 min, the genomic DNA was immediately used for the PCR reaction. The latter was carried out in a peqSTAR 96 Universal Thermocycler (peqLab) using the JumpStart REDTaq Ready Mix (Sigma Aldrich) with the following primers (sequences 5′-3′) of the Rh1 and cry genes (the cry gene was used as a reference gene):

-

Rh1: TCTGTATTTCGAGACCTGGGTGCTC; GACATGAACCAGATGTAGGCAATCTTGC

-

cry: CGGAGTTGATGAATGTCC; GCATGTTTCGCTTTACGG.

qPCR

The relative mRNA levels of Rh1 and Rh7 in different fly strains were quantified via qPCR in 1- and 10-day-old flies as described in Senthilan and Helfrich-Förster (2016). Total RNA was extracted from the retinas of five flies per strain and age using the Quick-RNA™ MicroPrep Kit from Zymo Research and reversely transcribed using the Qiagen QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit. qPCRs were then carried out with the Bioline SensiFAST SYBR No-ROX Kit in combination with the Qiagen Rotor-Gene Q machine and 0.1 µM PCR primers. For each strain and tissue, three biological replicates were examined, and for each replicate, two PCRs were run. The relative mRNA levels were calculated using the ΔCT equation and alpha-tubulin was used as the reference gene. To exclude gDNA contamination, we designed our Rhodopsin primers in an intron-spanning way, so that the PCR products obtained from the cDNA and the gDNA will differ by size and by melting temperature.

The following genes and primers (sequences 5′-3′) were used:

-

Rh1: GGAGTAGAAGATCAGGTATGAGCGTG; TGCCTACATCTGGTTCATGTCGAGC

-

Rh7: CATCTGCGACTTTCTGATGCTCATC; GGATGCACCACCACATTGTACCGATC

-

Alpha-tub: TCTGCGATTCGATGGTGCCCTTAAC; GGATCGCACTTGACCATCTGGTTGGC.

Rh7 antibody generation

Two different peptide antibodies against Rh7 were generated: one against a 21-mer peptide in the intracellular domain of Rh7 (aa411-431: TRSSYMTRSRSSFTHRLRTST) and one against an 18-mer peptide in the extracellular domain of Rh7 (aa54-71: TESSAVNVGKDHDKHVND). For the first antibody, the cDNA fragment encoding the intracellular peptide was cloned into the bacterial expression vector pQE40 (Qiagen). The recombinant protein (intracellular peptide coupled to dihydrofolate reductase) was expressed in Escherichia coli and used to immunize rabbits. These experiments were registered and conducted according to the legal animal care regulations (RP Karlsruhe, AZ. 35-9185.82/977/99). The second antibody was also generated in rabbits, but by Pineda Antikörper-Service (Berlin, Germany). It was affinity purified using the original peptide bound to Sepharose 6B columns prior to use. Before immunization, serum samples were taken to obtain preimmune serum as negative control for unspecific immunoreactivity. Dot blot analysis was used to confirm the selective binding of Rh7 antibody to the purified peptide.

Histology and immunocytochemistry

For evaluating the fine-structure of the retina, fly heads were embedded in Epon and 0.2 µm-thick semi-thin sections of the eyes (from distal to proximal) and were cut with a microtome (Leica Ultracut). After mounting on glass slides, the sections were stained with methylene-blue (Romeis 2015). Ten flies of WT controls, ninaE 17 mutants, and ninaE 17 mutants with Rh7 expression in R1–6 (Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17), respectively, were stained and analyzed at the age of 1, 6, 10 days, and 5 weeks. The rhabdomere size of R1–6 was determined in 10-day-old flies in ImageJ as stated below.

For anti-Rh7, anti-Rh1, and anti-RDHB (visualizing the pigment cells surrounding the photoreceptor cells; Wang et al. 2012) immunocytochemistry, retinas of 4–6-day-old flies were dissected and fixed as described in Hsiao et al. (2012). Primary antibodies were applied for 2 days at room temperature (rabbit anti-Rh7 at 1:100; mouse anti-Rh1 from Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank at 1:100 and rabbit anti-RDHB, kindly donated by Craig Montell, at 1:100). Fluorescent secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 488, 555, 635, Invitrogen) were applied overnight (at 1:1000). Immunostainings were visualized by confocal microscopy (Leica TCS SPE).

Evaluation of rhabdomere size

Rhabdomere size of 1-day-old flies was determined by measuring the areas of single rhabdomeres in five ommatidia of three different retinas with ImageJ (function “measure” under “analyze”). This was done for R1–6 and R8 of ninaE 17 mutants, Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 and Rh1–Rh7 flies, respectively. In all cases, cross sections at the level of R8 were taken for the measurements. The sizes of R1–6 were averaged for each ommatidium. A mean size for a typical R1–6 rhabdomere was then determined by averaging the values for all 15 ommatidia.

Deep pseudopupil

The deep pseudopupil was determined in vivo in 6-day-old white-eyed flies under white orthodromic illumination as described in Franceschini and Kirschfeld (1971). Flies were anaesthetized and glued to a glass slide with the left eye oriented to the top and placed under a stereo microscope. The eye was illuminated with a cold light source (KL 1500 LED plus, Leica). The objective (Planapo 1.6×, n:A. 0.24) was focused onto a region below the crystal cones at which R7 was seen best.

ERG recordings

ERG recordings were performed in 6- and 10-day-old flies at 20 °C as stated in Mazzotta et al. (2013). Before each experiment, flies were dark-adapted for 15 min. A halogen lamp (Spindler & Hoyer) was used for the generation of white light stimuli of 400 ms duration and different intensities. The halogen lamp emits light between 380 and 1000 nm as measured by a QE6500 spectrophotometer (Fig. 1). For generating light in the UV range, an LED with a λ max of 370 nm (Roithner) was used (Fig. 1). To keep the flies in a reasonably dark-adapted state, the inter-stimulus interval was 20 s. Experiments were run starting with the lowest light intensity to minimize adaptation effects. Maximum light intensity was 9.75 × 1014 photons cm−2 s−1. The receptor potential amplitudes of the electroretinogram (ERG) responses were plotted as a function of the related light intensity to yield irradiance response curves. Each curve was obtained from n = 7–13 flies. The sum of the measured receptor potential amplitudes for all light intensities were calculated for each single fly and statistically compared between different strains.

Results

Low expression levels of Rh7 in the retina can be enhanced by ectopic expression in R1–6

In comparison with Rh1, Rh7 was expressed at rather low levels in the retina of the control flies (backcross) (<1:1000, Fig. 2a). As soon as under control of the Rh1 promotor (Rh1–Rh7 or Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 flies), Rh7 levels rose to the level of retinal Rh1 expression (Fig. 2a). Thus, ectopic Rh7 expression led to high levels of Rh7 mRNA. Immunostaining with our Rh7 antibodies showed that the Rh7 mRNA was also translated into Rh7 protein. Whereas the Rh7 antibodies could not detect Rh7 in the retina of wild-type flies, Rh7 was clearly detectable in R1–6 of Rh1–Rh7 flies (Fig. 2b). Both Rh7 antibodies yielded the same results. Staining in wild-type flies (WTCS, y−w1118 and the backcross) was quite variable and sometimes gave a uniform background staining of all tissues (see Fig. 2b) and sometimes staining in the interrhabdomeric space, as can be seen in the retina of the Rh1–Rh7 flies, as shown in Fig. 2b. However, the rhabdomeres of the photoreceptor cells were never labeled in wild-type flies, suggesting that Rh7 levels of wild-type flies are below the detection limit. This coincides with the low mRNA expression levels of Rh7 (Fig. 2a).

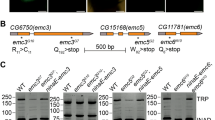

Rh7 and Rh1 expressions in the compound eyes. a qPCRs of Rh1 and Rh7 expressions (cyan or magenta bars, respectively) in the retina of 1- and 10-day-old flies, and in case of sev LY3 of 6-day-old flies. All flies are in a white-eyed y − w 1118 background. For details, see text. b Anti-Rh1 and anti-Rh7 double labeling in whole-mount retinas of Rh1–Rh7 and control flies (backcross). Rh1 is visualized in cyan and Rh7 in magenta. Whereas no specific Rh7 staining is visible in the R1–6 rhabdomeres of control flies, the Rh7 antibody labels all R1–6 rhabdomeres of Rh1–Rh7 flies. These stainings are obtained with the anti-Rh7 antibody raised against the 18-mer peptide in the extracellular domain (aa54-71) of Rh7. Scale bar 5 µm. c PCR products of Rh1 and cryptochrome (cry) genes from two flies (1, 2) per genotype, respectively. ninaE 17 mutants lack the PCR product of Rh1. d Anti-Rh1 and anti-RDHB (retinol dehydrogenase B) double labeling in whole-mount retinas of the different genotypes. RDHB marks the pigments cells that surround the photoreceptor cells of each ommatidium. ninaE 17 mutants lack Rh1 labeling

ninaE 17 mutants carry a 1.6 kb deletion in the 5′ region of the Rh1 gene with no detectable Rh1 transcript on an agarose gel (O’Tousa et al. 1985). As expected, the genomic DNA PCR yielded no visible Rh1 gene product on the gel (Fig. 2c), while using qPCR, which is more sensitive, we still detected marginal mRNA signals in the ninaE 17 mutants (Fig. 2a). This residual expression is probably a result of the incomplete deletion in the Rh1 gene. Residual Rh1 expression was elevated after expressing Rh7 in R1–6 of ninaE 17 mutants (Fig. 2a) most probably because Rh7 expression prevented the degeneration of R1–6 (see below). Nevertheless, the Rh1 protein was not detectable at all in ninaE 17 mutants nor in Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 mutants (Fig. 2d). This coincides with previous studies showing that ninaE 17 mutants lack a functional Rh1 protein and they are, therefore, considered as Rh1 null mutants (Bentrop et al. 1997).

Most interestingly, the degeneration of R1–6 in 10-day-old ninaE 17 mutants did not reduce Rh7 mRNA levels (Fig. 2a), suggesting that Rh7 is normally not expressed in R1–6. Furthermore, Rh7 is still present in sevenless LY3 (sev LY3) mutants that lack photoreceptor cell R7 (Fig. 2a) indicating that Rh7 is also not expressed in R7 and pinpointing to an expression of Rh7 in R8. Indeed, a reporter line carrying the gene for the green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the first intron of the Rh7 gene showed weak GFP expression in R8 (Kistenpfennig et al. 2017, in preparation).

Rh7 can partially replace Rh1 in maintaining rhabdomere structure of R1–6

To test whether Rh7 can rescue the retinal degradation provoked by the ninaE 17 mutation, we first analyzed the deep pseudopupil of 6-day-old flies without Rh1, with Rh7 instead of Rh1, and with Rh1 and Rh7 in R1–6. The deep pseudopupil is an optical phenomenon that comes about by superposition of the virtual images of the rhabdomeres of neighboring ommatidia (Franceschini and Kirschfeld 1971). The deep pseudopupil can only be seen when all rhabdomeres are regularly arranged. Consequently, it disappears in ninaE 17 mutants, in which the rhabdomeres collapse (Fig. 3a). We found the deep pseudopupil in control flies as well as in flies that express Rh1 and Rh7, but not in flies that express Rh7 instead of Rh1 (Fig. 3a). This indicates that the rhabdomeres are not regularly arranged in flies that express Rh7 instead of Rh1 suggesting that Rh7 cannot rescue retinal degeneration in flies lacking Rh1.

Rh7 can partially rescue maintenance of Rh1 in of R1–6. a Deep pseudopupil in the eyes of 6-day-old WT-control flies (y − w 1118), flies that express Rh7 in addition to Rh1 in the outer receptor cells (Rh1–Rh7), Rh1 null mutants (ninaE 17), and flies that express Rh7 instead of Rh1 (Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17). An enlarged image of the deep pseudopupil is shown in the insets at the left bottom of each picture. The arrangement and numbering of the rhabdomeres are shown in the inset at the right bottom of the WT-control picture. Only control flies and Rh1–Rh7 flies show a regular deep pseudopupil indicating a correct arrangement of R1–6 and their rhabdomeres. In ninaE 17 and Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 flies, only the inner receptor cells R7 and R8 show a weak yellowish pseudopupil (arrowhead). All flies are in a white-eyed background (applies also for b–d). b Semi-thin sections of retinas of 10-day-old flies (the same fly strains, as depicted in Fig. 2a). Arrowheads point to photoreceptor cell 8 that are present in all ommatidia of WT control, Rh1–Rh7 and Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 flies (together with photoreceptor cell 7 highlighted by open arrowheads). In Rh1 null mutants (ninaE 17), receptor cells R7/8 are present in ~60% of the ommatidia. Receptor cells R1–6 degenerate in ninaE 17 mutants and are completely absent in all ommatidia. Flies that express Rh7 instead of Rh1 still retain small rhabdomeres of R1–6 (arrows). Flies that express Rh7 in addition to Rh1 have normally sized rhabdomeres, but they show holes (exemplary marked by asterisks) between the rhabdomeres, suggesting that an excess of rhodopsin disturbs the general morphology of the retina. Scale bar 5 µm. c Semi-thin sections of retinas of 5-week-old flies. ninaE 17 mutants lack all photoreceptors and rhabdomeres, whereas these were still present in Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 flies. The retina of all flies, including the WT controls, show some degeneration visible by the holes between the ommatidia (asterisks). d Horizontal semi-thin sections of the right retina, lamina and medulla of 5-week-old ninaE 17 and Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 flies, respectively. In ninaE 17 mutants the retina (RE) is filled with holes (asterisks) and lost its usual regular structure, the lamina (LA) is rather thin and also full of holes and the medulla (ME) contains holes in its distal part, where R7 and R8 end. In contrast, Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 flies retain the regular structure of the retina [only 2 holes are visible in this section (asterisks)], the lamina is thicker than that of Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 flies and the distal medulla is virtually free of holes. Please note that the stronger staining of the ninaE 17 semi-thin section is also typical for degenerating tissue (Kretschmar et al. 1997)

To investigate whether the missing deep pseudopupil is indeed caused by rhabdomere degeneration or just by an irregular arrangement of the rhabdomeres, we additionally performed semi-thin sections of the fly retina. One day after eclosion, the rhabdomeres were still clearly visible in homozygous ninaE 17 mutants, independent of the presence or absence of Rh7 (not shown). However, 6 and 10 days after eclosion, the rhabdomeres of R1–6 were completely absent in ninaE 17 mutants, whereas we still saw small rhabdomeres of R1–6 in the ommatidia of Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 flies and normal rhabdomeres in the ommatidia of Rh1–Rh7 (Fig. 3b). The R1–6 rhabdomeres of Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 flies had half the size of wild-type rhabdomeres, whereas the R8 rhabdomeres were of equal size in all strains (Table 1). Besides the size differences of the R1–6 rhabdomeres, we observed holes between the ommatidia in Rh1–Rh7 and Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 flies that were not visible in controls (asterisks in Fig. 3b). Such holes are indicative of ongoing neurodegeneration (Kretschmar et al. 1997) and have been already described for mutants lacking Rh1 (Kurada and O’Tousa 1995; Bentrop et al. 1997) as well as for flies expressing overactive Rh1 (Iakhine et al. 2004; reviewed by Shieh 2011). Rhabdomeres of R7 and R8 were always visible in the ommatidia of Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 flies, whereas they were present in 95 and 60% of the ommatidia in 6- and 10-day-old ninaE 17 mutants, respectively. The latter observation indicates that even the inner photoreceptor cells degenerate with increasing age in ninaE 17 mutants. Thus, Rh7 appears to prevent not only the degeneration of R1–6 but also that of R7/R8.

In 5-week-old flies, the differences between ninaE 17 mutants and Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 flies became most evident. Whereas ninaE 17 mutants of that age showed a severe degeneration of the entire retina and lacked all rhabdomeres, Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 flies still retained small rhabdomeres in R1–6 and rather normal rhabdomeres of R7 and R8 (Fig. 3c). Holes between the rhabdomeres were now visible even in control flies, but occurred still more frequently in Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 flies (asterisks in Fig. 3c). In ninaE 17 mutants, even the target neuropils of the photoreceptor cells degenerated. This was most evident in the lamina, in which the axons of R1–6 terminate, and to a lesser degree in the medulla, in which the axons of R7 and R8 terminate (Fig. 3d). In contrast, Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 flies showed no such signs of degeneration in the lamina and medulla (Fig. 3d).

We conclude that Rh7 can partially replace Rh1 in its rhabdomere and photoreceptor maintenance role. R1–6 photoreceptor cells and their rhabdomeres were present in Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 flies, but they were significantly smaller than in control flies and obviously not arranged in a sufficient regular manner to enable a deep pseudopupil. This irregular arrangement is hard to see on our semi-thin sections even not at a bigger field of the retinal section (Fig. S1). Nevertheless, one must confess that a precise superposition depends on a formidable regularity in the architecture of the compound eye, such as a constancy of the center-to-center distance between the seven rhabdomere distal endings (Franceschini 1972). Already, small deviations may result in a failure to detect a deep pseudopupil.

Rh7 cannot rescue the electroretinogram (ERG) of ninaE 17 mutants

Since Rh7 can partially rescue rhabdomere degeneration in ninaE 17 mutants, it may also be able to activate the phototransduction cascade upon light stimulation. To test this, we performed extracellular ERG measurements on 6- and 10-day-old white-eyed ninaE 17 and Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 flies as well as 6-day-old white-eyed control flies (backcross) and flies that express Rh1 and Rh7 in R1–6 (Fig. 4). The ERG represents the summed responses of all retinal cells plus the postsynaptic neurons in the lamina to light. There are two primary features of the ERG: the maintained component (or the receptor potential), which results from the activity in the retina, and the on- and off transients, which occur due to postsynaptic activity in the lamina (Pak et al. 1969) (Fig. 4a). R1–6 are the only cells that transmit the evoked signals to the lamina. Therefore, the on- and off transients are absent in ninaE 17 mutants that lack functional R1–6. Furthermore, the receptor potential is rather low in ninaE 17 mutants, since it consists only of the light responses evoked in R7 and R8. We found that the ERG of 6-day-old Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 flies was not significantly different from ninaE 17 mutants, neither in shape nor in amplitude: The on- and off transients were completely absent (Fig. 4a) and the residual receptor potential in response to increasing light intensity was not significantly different from that of ninaE 17 mutants (Fig. 4c). The same was true under UV light. Only the shape of the ERGs under UV slightly differed from that under white light (Fig. 4a): R1–6 of control and Rh1–Rh7 flies responded to UV, so rapidly that the amplitude of the on transient was lowered. Furthermore, in ninaE 17 and Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 flies, which lacked on- and off transients, a small overshoot of the receptor potential was visible (arrows in Fig. 4a). These differences were already reported earlier (Bentrop et al. 1997). Nevertheless, even UV light could not provoke higher receptor potentials in flies that expressed R7 instead of Rh1 or in addition to Rh1 (Fig. 4a, b). We conclude that Rh7 is not able to activate the phototransduction cascade in R1–6 and, thus, is not a functional rhodopsin in these cells. The receptor potential present in ninaE 17 and Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 mutants appears to originate entirely from R7/R8. This is supported by the ERG response curves of 10-day-old ninaE 17 mutants, in which our histological analysis revealed a beginning degeneration of R7/R8: Their ERG response showed a clear tendency to decrease (Fig. 4c).

Ectopic Rh7 in R1–6 does not affect the ERG responses. a ERGs to white and UV (370 nm) light-pulses of 400 ms of 6-day-old WT-control flies (backcross), flies that express Rh7 in addition to Rh1 in the outer receptor cells (Rh1–Rh7), Rh1 null mutants (ninaE 17) and flies that express Rh7 instead of Rh1 (Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17). Control flies and flies expressing Rh7 in addition to Rh1 show normal ERG responses with lights-on and lights-off transients and a receptor potential of ~10 mV in between the two. Rh1 null mutants and flies that express Rh7 instead of Rh1 lack the lights-on and lights-off responses that depend on R1–6 and show a significantly lower ERG amplitude. Under UV light, ninaE 17 and Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 mutants exhibit a small overshoot in their receptor potential (small arrow). b Amplitude of the receptor potential dependent on log irradiance (dose–response) in backcross and Rh1–Rh7 flies under white and UV light. The columns to the right of the dose–response curves indicate the summed receptor amplitudes used for statistical comparison. c Amplitude of the receptor potential in 6- and 10-day-old ninaE 17 and Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 flies. The presence of Rh7 does not cause any differences in the ERG amplitude of 6-day-old flies. In 10-day-old flies, ninaE 17 mutants tend to show lower responses, probably due to the degeneration of photoreceptor cells R7/8 (for details see text)

Discussion

Many animals express more than one Rhodopsin molecule in their eyes to enhance light sensitivity and to enable color vision. Mosquitoes express even several rhodopsins in one photoreceptor cell (R7) making them responsive to a broad spectrum of visible and UV light and enabling them to be active at very dim light (Hu et al. 2011, 2014). The fruit fly D. melanogaster possesses six well-characterized Rhodopsins and a seventh Rhodopsin (Rh7) with unknown function that might be co-expressed with the others. Rh7 seems to be an ancient type of Rhodopsin that is conserved among different arthropods, including species as Limulus polyphemus and Daphnia pulex (Senthilan and Helfrich-Förster 2016). Rh7 possesses nearly all important features for a visual functional protein, but it lacks the highly conserved QAKK motif, which is, together with the DRY motif, important for G-protein binding and consequently for the activation to the G-protein-coupled cascade. Therefore, it is unknown, whether it is a functional Rhodopsin. Here, we tested whether Rh7 can replace the function of Rh1 by expressing it instead of Rh1 in R1–6.

We found that Rh7 can partially overtake the functions of Rh1. It can fairly replace Rh1 in its rhabdomere maintenance function, but it cannot activate the phototransduction cascade in R1–6, at least not under our experimental conditions. We cannot exclude that Rh7 is a UV-sensitive Rhodopsin with a sensitivity maximum below 320 nm. Our halogen lamp emits almost no light at wavelengths below 400 nm (Fig. 1) and the UV-LED with λ max at 370 nm cannot excite Rhodopsins with sensitivity maxima below 320 nm given that the half width of a typical Rhodopsin absorption spectrum is ~100 nm (Salcedo et al. 1999). It is possible that Rh7 is a UV-sensitive Rhodopsin, because it retains primary protein sequence motifs that are characteristic of invertebrate UV pigments, such as the lysine at position 168 (position 110 in Rh1) and the DRY motif (Salcedo et al. 2003; Hu et al. 2014), but it remains questionable that Rh7 can have λ max below 320 nm. Drosophila UV Rhodopsins, Rh3 and Rh4, have sensitivity maxima at 345 and 375 nm, respectively (Feiler et al. 1992) and other invertebrate UV Rhodopsins are sensitive in the same wavelength range (Popp et al. 1996; Smith et al. 1997; Chase et al. 1997; Salcedo et al. 1999). On the other hand, there are also data supporting the notion that Rh7 is sensitive to visible light, because it contains a tyrosine at position 191 that is also present in all other visible-light-detecting Rhodopsins, such as Rh1, Rh2, Rh5, and Rh6, but changed into a phenylalanine in the UV-sensitive Rh3 and Rh4 (Chou et al. 1996). In sum, it is unlikely that we have been unable to excite Rh7 with our lighting system.

Furthermore, we cannot completely exclude that Rh7 shows extremely weak and slow ERG responses as found for the mosquito Rh7 ortholog Op10 when expressed in R1–6 of D. melanogaster (Hu et al. 2014). Hu et al. (2014) used a modified norpA;ninaE 17 mutant background, in which norpA is activated only in R1–6. The norpA gene codes for the phospholipase C-β, which is an important component in the phototransduction cascade of all Drosophila photoreceptor cells (Bloomquist et al. 1988). Eliminating norpA in all photoreceptor cells except for R1–6 allowed measuring the activity of the ectopically expressed Op10 without interference from the R7 and R8 cells. In our experiments, R7 and R8 were still active and are responsible for the small receptor potential in ninaE 17 and Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 mutants (Fig. 4). These responses might have masked putative weak responses of Rh7. Nevertheless, we do not think that this is likely for the following reasons: (1) we compared the ERG responses between ninaE 17 and Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 mutants at different light intensities. Thus, at high intensities, we should have seen even small differences provoked by Rh7. (2) The activity of R1–6 provokes on- and off transients in the lamina that were clearly visible in the ERGs of WT flies, but completely absent in ninaE 17 mutants (Fig. 4). In none of the measured ERGs of Rh1–Rh7;ninaE 17 mutants, on- and off transients were present. This clearly indicates that Rh7 cannot activate the phototransduction cascade in R1–6.

The inability of Rh7 to activate the phototransduction cascade in R1–6 does not mean that Rh7 is not a functional photopigment. It may signal via a different phototransduction cascade that is absent in R1–6. Our data indicate that Rh7 is normally not expressed in R1–6. From sequence alignment, Rh7 is closely related to Drosophila Rh3, Rh4, and Rh5 genes (Senthilan and Helfrich-Förster 2016), suggesting that it is rather expressed in the inner instead the outer receptor cells, and we have first indications that Rh7 is expressed in the inner photoreceptor cell R8 (Kistenpfennig et al. in preparation). In mosquitos, the ortholog of Drosophila Rh7, Op10, is expressed in the inner receptor cell R7 together with Op8 (Hu et al. 2014). Although Op10 was able to activate the phototransduction cascade in R1–6 of D. melanogaster, it could do so only very weakly, suggesting that it usually operates with different signaling molecules that are not present in R1–6 (Hu et al. 2014). That the inner photoreceptor cells of D. melanogaster may use a different phototransduction cascade that works independently from the phospholipase C-ß which has been suggested by previous studies concerning circadian photoreception (Veleri et al. 2007; Szular et al. 2012).

It is also possible that Rh7 signals via a second Rhodopsin present in the inner photoreceptor cells. G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), including Rhodopsin-like GPCRs, can form dimers (Gurevich and Gurevich 2008a, b; Hiller et al. 2013). The assumption that Rh7 may interact with another Rhodopsin to exert its function is supported by the fact that Rh7 and its homologues lack the highly conserved QAKK motif, which is, together with the DRY motif, important for G-protein binding and consequently for the activation of the G-protein-coupled cascade (see above). Thus, Rh7 might signal via a second Rhodopsin and not by itself. Most interestingly, Rh7 has unusually long C- and N-terminal tails that are well suited for the interaction with other proteins (Senthilan and Helfrich-Förster 2016).

At present, we cannot answer the question, in which photoreceptor cell Rh7 is working and what is the way of its action. Its presence in most groups of arthropods, excluding those living in aphotic environments, suggests that it has a conserved function in light signaling either as visual or as non-visual Rhodopsin (Senthilan and Helfrich-Förster 2016). Further studies are needed to answer this interesting question.

References

Adams MD, Celniker SE, Holt RA, Evans CA, Gocayne JD, Amanatides PG, Scherer SE, Li PW, Hoskins RA, Galle RF et al (2000) The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster. Science 287:2185–2195

Ahmad ST, Natochin M, Artemyev NO, O’Tousa JE (2007) The Drosophila rhodopsin cytoplasmic tail domain is required for maintenance of rhabdomere structure. FASEB J 21:449–455

Applebury ML, Antoch MP, Baxter LC, Chun LL, Falk JD, Farhangfar F, Kage K, Krzystolik MG, Lyass LA, Robbins JT (2000) The murine cone photoreceptor: a single cone type expresses both S and M opsins with retinal spatial patterning. Neuron 27:513–523

Basler K, Hafen E (1988) Control of photoreceptor cell fate by the sevenless protein requires a functional tyrosine kinase domain. Cell 54(3):299–311

Behnia R, Desplan C (2015) Visual circuits in flies: beginning to see the whole picture. Curr Opin Neurobiol 34:125–132

Bentrop J (1998) Rhodopsin mutations as the cause of retinal degeneration. Classification of degeneration phenotypes in the model system Drosophila melanogaster. Acta Anat (Basel) 162:85–94

Bentrop J, Schwab K, Pak WL, Paulsen R (1997) Site-directed mutagenesis of highly conserved amino acids in the first cytoplasmic loop of Drosophila Rh1 opsin blocks rhodopsin synthesis in the nascent state. EMBO J 16(7):1600–1609

Bloomquist BT, Shortridge RD, Schneuwly S, Perdew M, Montell C, Steller H, Rubin G, Pak WL (1988) Isolation of a putative phospholipase C gene of Drosophila, norpA, and its role in phototransduction. Cell 54(5):723–733

Chase MR, Bennett RR, White RH (1997) Three opsin-encoding cDNAs from the compound eye of Manduca sexta. J Exp Biol 200:2469–2478

Chou W-H, Hall KJ, Wilson DB, Wideman CL, Townson SM, Chadwell LV, Britt SG (1996) Identification of a novel Drosophila opsin reveals specific patterning of the R7 and R8 photoreceptor cells. Neuron 17(6):1101–1115

Feiler R, Harris WA, Kirschfeld K, Wehrhahn C, Zuker CS (1988) Targeted misexpression of a Drosophila opsin gene leads to altered visual function. Nature 333:737–741

Feiler R, Bjornson R, Kirschfeld K, Mismer D, Rubin GM, Smith DP, Socolich M, Zuker CS (1992) Ectopic expression of ultraviolet-rhodopsins in the blue photoreceptor cells of Drosophila: visual physiology and photochemistry of transgenic animals. J Neurosci 12:3862–3868

Franceschini N (1972) Pupil and pseudopupil in the compound eye of Drosophila. In: Wehner R (ed) Information processing in the visual system of arthropods. Springer, Berlin, pp 75–82. ISBN 3-540-06020-0

Franceschini N, Kirschfeld K (1971) Pseudopupil phenomena in the compound eye of Drosophila. Kybernetik 9:159–182

Gurevich VV, Gurevich EV (2008a) GPCR monomers and oligomers: it takes all kinds. Trends Neurosci 31(2):74–81

Gurevich VV, Gurevich EV (2008b) Rich tapestry of G protein-coupled receptor signaling and regulatory mechanisms. Mol Pharmacol 74(2):312–316

Harris WA, Stark WS, Walker JA (1976) Genetic dissection of the photoreceptor system in the compound eye of Drosophila melanogaster. J Physiol 256:415–439

Hiller C, Kühhorn J, Gmeiner P (2013) Class A G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) dimers and bivalent ligands. J Med Chem 56(17):6542–6559

Hsiao HY, Johnston RJ, Jukam D, Vasiliauskas D, Desplan C, Rister J (2012) Dissection and immunohistochemistry of larval, pupal and adult Drosophila retinas. J Vis Exp 69:e4347. doi:10.3791/4347

Hu X, Whaley MA, Stein MM, Mitchell BE, O’Tousa JE (2011) Coexpression of spectrally distinct rhodopsins in Aedes aegypti R7 photoreceptors. PLoS One 6(8):e23121

Hu X, Leming MT, Whaley MA, O’Tousa JE (2014) Rhodopsin coexpression in UV photoreceptors of Aedes aegypti and Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes. J Exp Biol 217:1003–1008

Iakhine R, Chrobna-Ornan I, Zars T, Elia N, Cheng Y, Selinger Z, Minke B, Hyde DR (2004) Novel dominant rhodopsin mutation triggers two mechanisms of retinal degeneration and photoreceptor desensitization. J Neurosci 24(10):2516–2526

Kistenpfennig C, Grebler R, Ogueta M, Hermann-Luibl C, Schlichting M, Stanewsky R, Senthilan PR, Helfrich-Förster C (2017) A new Rhodopsin influences light-dependent daily activity patterns of fruit flies. J Biol Rhythms. (in preparation)

Knox BE, Salcedo E, Mathiesz K, Schaefer J, Chou WH, Chadwell LV, Smith WC, Britt SG, Barlow RB (2003) Heterologous expression of limulus rhodopsin. J Biol Chem 278(42):40493–40502

Kretschmar D, Hasan G, Sharma S, Heisenberg M, Benzer S (1997) The Swiss Cheese mutant causes glial hyperwrapping and brain degeneration in Drosophila melanogaster. J Neurosci 17(19):7425–7432

Kumar JP, Ready DF (1995) Rhodopsin plays an essential structural role in Drosophila photoreceptor development. Development 121:4359–4370

Kumar JP, Bowman J, O’Tousa JE, Ready DF (1997) Rhodopsin replacement rescues photoreceptor structure during a critical developmental window. Dev Biol 188:43–47

Kurada P, O’Tousa JE (1995) Retinal degeneration caused by dominant rhodopsin mutations in Drosophila. Neuron 14:571–579

Leonard DS, Bowman VD, Ready DF, Pak WL (1992) Degeneration of photoreceptors in rhodopsin mutants of Drosophila. J Neurobiol 23:605–626

Mazzoni EO, Desplan C, Celik A (2004) ‘One receptor’ rules in sensory neurons. Dev Neurosci 26:388–395

Mazzotta G, Rossi A, Leonardi E, Mason M, Bertolucci C, Caccin L, Spolaore B, Martin AJ, Schlichting M, Grebler R, Helfrich-Förster C, Mammi S, Costa R, Tosatto SCE (2013) Fly cryptochrome and the visual system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:6163–6168

O’Tousa JE, Baehr W, Martin RL, Hirsh J, Pak WL, Applebury ML (1985) The Drosophila ninaE gene encodes an opsin. Cell 40:839–850

Pak WL, Grossfield J, White NV (1969) Nonphototactic mutants in a study of vision of Drosophila. Nature 222:351–354

Popp MP, Grisshammer R, Hargrave PA, Smith WC (1996) Ant opsins:sequences from the Saharan silver ant and the carpenter ant. Invert Neurosci 1:323–329

Posnien N, Hopfen C, Hibrant M, Ramos-Womack M, Murat S, Schönauer A, Herbert SL, Nunes MDS, Arif S, Breuker CJ, Schlötterer C, Mitteroecker P, McGregor AP (2012) Evolution of eye morphology and Rhodopsin expression in the Drosophila melanogaster species subgroup. PLoS One 7(5):e37346

Rister J, Desplan C, Vasiliauskas D (2013) Establishing and maintaining gene expression patterns: insights from sensory receptor patterning. Development 40:493–503

Romeis B (2015) Mikroskopische Technik. M Mulisch, U Welsch. 19 Auflage. Springer Spektrum, Heidelberg, ISBN 978-3-642-55189-5

Salcedo E, Huber A, Henrich S, Chadwell LV, Chou WH, Paulsen R, Britt SG (1999) Blue- and green-absorbing visual pigments of Drosophila: ectopic expression and physiological characterization of the R8 photoreceptor cell-specific Rh5 and Rh6 rhodopsins. J Neurosci 19:10716–10726

Salcedo E, Zheng L, Phistry M, Bagg EE, Britt SG (2003) Molecular basis for ultraviolet vision in invertebrates. J Neurosci 23(34):10873–10878

Senthilan PR, Helfrich-Förster C (2016) Rhodopsin 7—the unusual Rhodopsin in Drosophila. PeerJ 4:e2427

Shieh B-H (2011) Molecular genetics of retinal degeneration. Fly (Austin) 5(4):356–368

Smith WC, Ayers DM, Popp MP, Hargrave PA (1997) Short wavelength sensitive opsins from the Saharan silver and carpenter ants. Invert Neurosci 3:49–56

Stavenga DG, Arikawa K (2008) One rhodopsin per photoreceptor: Iro-C genes 6 break the rule. PLoS Biol 6:e115

Szular J, Sehadova H, Gentile C, Szabo G, Chou WH, Britt SG, Stanewsky R (2012) Rhodopsin 5- and Rhodopsin 6-mediated clock synchronization in Drosophila melanogaster is independent of retinal phospholipase C-β signaling. J Biol Rhythms 27(1):25–36

Terakita A (2005) The opsins. Genome Biol 6:213

Townson SM, Chang BS, Salcedo E, Chadwell LV, Pierce NE, Britt SG (1998) Honeybee blue- and ultraviolet-sensitive opsins: cloning, heterologous expression in Drosophila, and physiological characterization. J Neurosci 18:2412–2422

Veleri S, Rieger D, Helfrich-Förster C, Stanewsky R (2007) Hofbauer-Buchner eyelet affects circadian photosensitivity and coordinates TIM and PER expression in Drosophila clock neurons. J Biol Rhythms 22:29–42

Wang X, Wang T, Ni JD, von Lintig J, Montell C (2012) The Drosophila visual cycle and de novo chromophore synthesis depends on rdhB. J Neurosci 32:3485–3491

Zuker CS, Cowman AF, Rubin GM (1985) Isolation and structure of a rhodopsin gene from D. melanogaster. Cell 40:851–858

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the German research foundation (DFG), GK 640 “Natural and artificial photoreceptors” and Collaborative research center SFB 1047 “Insect timing”, project A2. The work was started in 2003 at the University of Regensburg and continued from 2009 onward at the University of Würzburg. We thank Erich Buchner for help with setting up the ERG recordings, Susanne Clemens-Richter for excellent technical support with semi-thin sections, Janina Kempf and Heike Wecklein for performing qPCRs, and Susanne C. Schreiber and Andreas Heinold for help with Rh7 constructs. We are grateful to Susanne Fischer, Cornelia Bleyl, Wolfgang Bachleitner, and Steffen Just for their work on Rh7 that is not included in the present manuscript to Andreas Huber for providing constructs and to Craig Montell for donating the antibody against RDGB. R.G. was sponsored by a grant of the German Excellence Initiative to the Graduate School of Life Sciences, University of Würzburg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval is not required for the study.

Informed consent

Formal consent is not required for the study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Grebler, R., Kistenpfennig, C., Rieger, D. et al. Drosophila Rhodopsin 7 can partially replace the structural role of Rhodopsin 1, but not its physiological function. J Comp Physiol A 203, 649–659 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00359-017-1182-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00359-017-1182-8