Abstract

Ultrasound imaging velocimetry (UIV) has received considerable interest as a tool to measure in non-transparent flows. So far, studies have only reported statistics for steady flows or used a qualitative approach. In this study, we demonstrate that UIV has matured to a level where accurate turbulence statistics can be obtained. The technique is first validated in laminar and fully developed turbulent pipe flow (single-phase, with water as fluid) at a Reynolds number of 5300. The flow statistics agree with the literature data. Subsequently, we obtain similar statistics in turbulent two-phase flows at the same Reynolds number, by adding solid particles up to volume fraction of 3 %. In these cases, the medium is completely opaque, yet UIV provides useable data. The error in the measurements is estimated using an ad hoc approach at a volume load up to 10 %. For this case, the errors are approximately 1.9 and 0.3 % of the centerline velocity for the streamwise and radial velocity components, respectively. Additionally, it is demonstrated that it is possible to estimate the local concentration in stratified flows.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The ubiquitous nature of two-phase flows has drawn continuous attention from the fluid mechanics community. Great advances have recently been made based on fully resolved numerical solutions of densely laden flows, made possible by efficient simulation tools and increased computing power (Picano et al. 2015). In contrast, experimental work has been lagging behind, despite the need for reliable validation data sets for aforementioned numerical studies. This can be attributed to the fact that the de facto standard flow measurement tools are optical techniques [laser Doppler anemometry, particle image velocimetry in all of its incarnations (Tropea et al. 2007)]. As soon as flows contain even a modest volume fraction of a dispersed phase, these methods tend to rapidly decrease in reliability. Most experimental studies are therefore restricted to low volume loads, the exact limit being determined by details of the dispersed phase, flow geometry and optical configuration [laser path length, image magnification, etc. (Linne et al. 2009)]. For small dispersed particles, volume loads of 0.5 % in a domain of 5–10 cm have been indicated as the limit (Poelma et al. 2006). For bubbles, experiments have been performed up to 1–4 % (Deen et al. 2002). An alternative is the use of very shallow (‘2D’) flow domains (Patil et al. 2015), which naturally introduces side-wall effects. For some experiments it is feasible to match the index of refraction of the dispersed and continuous phases (Wiederseiner et al. 2011). This approach is often expensive and relies on a limited set of material combinations (thus fixing density ratios, viscosity, etc.). Note that the limitation of optical techniques in turbid or opaque flows also prevent applications outside the laboratory, e.g. for in-line process monitoring.

Several alternative modalities have been introduced to study opaque flows, such as x-ray imaging (Heindel 2011) and magnetic resonance imaging (Elkins et al. 2009). The former only presents an image integrated along the beam paths (i.e. ‘averaged’ along the out-of-plane direction), complicating the analysis of instantaneous, three-dimensional flows (Jamison et al. 2012). MRI has been used successfully for flow measurements in complex and turbulent flows (Van Ooij et al. 2011; Jullien and Lemonnier 2012). However, it is an expensive and complex technique, with restrictions on material choice for the entire experimental facility. In recent years, ultrasound imaging velocimetry (UIV; also known as ‘echo-PIV’) has been introduced as a relatively inexpensive, safe and easy option for flow measurement in non-transparent conditions (Kim et al. 2004; Poelma et al. 2011, 2012).

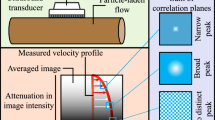

UIV is an implementation of particle image velocimetry that replaces conventional imaging (using lasers and cameras) with echography. Extensive details can be found in aforementioned papers. Many validation studies have appeared in the last few years, benchmarking the technique against, e.g. optical PIV or theoretical velocity profiles (Kim et al. 2004; Poelma et al. 2011; Beulen et al. 2010; Walker et al. 2014). However, all of these studies used time-averaged data, or phase-averaged profiles in the case of pulsatile flow. To study turbulent flows, it is necessary that instantaneous velocity fields can be obtained accurately. The time-averaged validation results were generally born out of necessity, due to the relatively low signal-to-noise ratio of echography images. Recent work has seen significant improvements in the processing of data specifically from echography: While previously generic PIV algorithms were applied, refined and dedicated approaches have been introduced that improve the accuracy and dynamic range of UIV (Poelma et al. 2012; Zhou et al. 2013; Poelma and Fraser 2013).

In this study, we demonstrate that UIV has matured to the state where turbulence statistics can be obtained reliably. This is done by first measuring single-phase, turbulent pipe flow. While UIV will not be the likely first choice for this flow, extensive reference data are available in the literature for this case. Subsequently, we demonstrate that it is also possible to measure in opaque two-phase flows at moderate volume fractions (here up to 3 %). Estimates for the concentration profile of the suspended particles are also feasible. For the two-phase flow, no comparison with the literature data is attempted and a detailed physical interpretation is avoided here; this part of the paper serves as a proof-of-principle of the technique, hopefully inspiring the two-phase flow community to introduce the method in the many application areas that may benefit from it.

2 Experimental details

In this section, the turbulent pipe flow facility and ultrasound measurement system are described. Both are discussed in greater detail elsewhere; only the basics are given here, as well as details specific to this study.

2.1 Flow facility

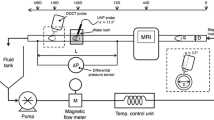

The main experiments for the single-phase validation are performed in the pipe flow facility as described by Trip et al. (2012). Note that this facility is in turn based on a version used in the earlier studies that will serve as reference for the single-phase results (Trip et al. 2012; Eggels et al. 1994; Hof et al. 2004; Van Doorne and Westerweel 2007).

The pipe flow facility consists of a 6-m-long pipe with an inner diameter (D) of 40 mm. The length of the pipe (150D) is sufficient for fully developed laminar flow up to approximately Re = 2500 (\(Re \equiv UD/\nu\), with U the mean velocity and \(\nu\) the kinematic viscosity). The flow in this pipe is driven by a pump (Nakakin sanitary rotary pump; model RM, controlled by Labview). Before entering the pipe, the flow is conditioned in a small settling chamber, containing a set of meshes, flow straighteners and a smooth contraction. Outflow from the pipe is into a chamber with an open surface, from which the flow returns to the pump via a flow metre (Krohne Altometer UFS500 ultrasonic flow metre).

Approximately 10 diameters upstream of the original measurement section (for optical PIV) a new test section is made specifically for UIV measurements, see also Fig. 1: along 6 cm, the top wall of the perspex pipe is reduced from 5 to approximately 0.5 mm thickness. A thin layer of Aquasonic 100 ultrasound transmission gel (Parker laboratories, Fairfield, NJ, USA) was added between the flat surface and the transducer. This greatly enhanced the image quality compared to mounting the transducer directly on the original pipe wall. Note that the signal reduction by the top wall is here mostly due to specular reflection (as a result of the acoustic impedance mismatch) and less so due to absorption by the wall material itself. For materials with a higher attenuation coefficient the reduction in the wall will have a greater effect. The bottom of the pipe created a strong reflection in the image, again due to the large difference in impedance of water and perspex. Therefore, a 1-cm-wide segment of the bottom wall was removed over the length of approximately 12 cm and replaced with an absorbent rubber material. Note that, unlike the top wall, this means that the bottom wall surface is no longer perfectly cylindrical. The effect on the flow is expected to be minimal, however. This was later also confirmed by the single-phase reference results.

For convenience, two coordinate systems are used: (x, y) represent the image coordinate system, with y = 0 representing the transducer surface and x the position along the transducer surface (i.e. the streamwise direction). For the velocity results, (x, r) are radial coordinates, with r = 0 representing the centerline.Footnote 1 The transducer could be translated in the direction perpendicular to the x, y-plane using a translation stage and it was placed in the centerplane of the pipe.

In addition to these main experiments, a gravity-driven pipe flow was used: a 1.5-m-long silicone rubber tube with an inner diameter of 1 cm was mounted horizontally and fed from a small elevated reservoir. The transducer was mounted just before the end of the tube. These experiments served to explore what the applicability of the technique was in an alternatively scaled set-up (i.e. the Reynolds number was comparable, but the diameter a factor four lower and the velocity a factor four higher). Furthermore, the smaller system volume allowed a more rapid turnaround compared to the 75–80 l of the main pipe flow facility. Based on the latter, also a mock-up was made of the test section: a small tube segment with identical modifications (flattened top wall and absorber, see Fig. 1), yet closed at both ends. This mock-up was used to quickly investigate the scattering properties and signal quality of particle suspensions.

2.2 UIV system

The ultrasound imaging system is based on a SonixTOUCH Research (Ultrasonix / bk Ultrasound), fitted with a linear transducer (L14-5/38). This transducer has 128 elements, distributed over a width of 38 mm, and is set to operate at 10 Mhz. This leads to an estimated image resolution of approximately 0.15 mm in the beam propagation direction. The resolution in the azimuthal direction at the focal plane is larger by a factor of F/D (the ratio of focal distance and the aperture size). For the selected values F = 2 cm and D = 1.3 cm, we find an azimuthal resolution of 0.23 mm at the focal location. The received signal is sampled at 40 Mhz and stored in both raw format and as ‘B-mode’ movies for reference. Data sets are recorded in sequences of several seconds, limited by a memory buffer. Note that the system runs in research mode, allowing full control of all acquisition parameters (beyond ‘patient safety’ restrictions) and access to raw signals.

Typical recording rates, limited by the sum of the time-of-flight for all lines that make up an image, were 90 frames/s. This number refers to an imaging depth of 4.5 cm and the use of the full transducer width. Reading out only the middle 64 elements and reducing the imaging depth by a factor two, both approximately double the acquisition rate. The recording rate effectively sets an upper lower limit on the interframe time (\(\Delta T\)) between successive frames, which in turn limits the maximum allowable displacement and thus velocity of tracer particles (as there are no means to change the image magnification, as in optical PIV). Using the interleaved approach, this limitation can be circumvented for the study of fast flows (\({>}0.5\) m/s) (Poelma and Fraser 2013).

The thickness of the measurement plane, equivalent to the light sheet thickness in conventional PIV, was determined by translating a small tethered sphere perpendicular to the imaged plane using a linear stage. Near the centerline of the pipe the intensity of the sphere image showed a bell-shaped intensity distribution, spanning 4.5 mm (width at half-height of the maximum intensity; corrected for the diameter of the sphere).

For the particles, there are several considerations, depending on whether the goal is to study single-phase flows (‘tracers’) or two-phase flows (‘dispersed phase’). They should be visible in the ultrasound image, leading to specific demands for their size and the impedance of the material. Furthermore, their settling velocity should be such that they do not settle—especially in lower-velocity parts of the facility (settling chamber, return pipe). The particles should be able to withstand the rotary pump and be available in bulk at reasonable costs.

For the single-phase experiments, Vestosint particles (Degussa-Hüls, Frankfurt, Germany) are used as tracer material, with a mean diameter of 56 \(\upmu m\) and a density of 1.016 \(\hbox {g/cm}^3\). The associated particle response time, based on Stokes’ drag law, is negligible (0.18 ms), as is the settling velocity. Previously, these particles have been used in optical PIV experiments (Scarano and Poelma 2009), but their material properties (Nylon 12) and size were found to also give good acoustic scattering behaviour.

For the two-phase flow experiments, 3M Zeeospheres G-850 were used (density 2.1 \(\hbox {g/cm}^3\), \(D_{50} = 40~\upmu \hbox {m}\), 95 % \({<}160~\upmu \hbox {m}\)). These have a comparable response time, but an appreciable settling velocity, approximately 1 mm/s in water. Note that they are not intended as flow tracers, but as a dispersed phase. The two-phase flow measurements will only provide velocity information for this dispersed phase, not for the continuous phase; see also the Discussion section. As the response time is small compared to the fluid time scales, it can be expected that the dispersed phase will follow the fluid motions to a great extent. Therefore, its velocity can also be determined using a correlation-based approach. If the particle motions would be uncorrelated, i.e. ‘random’ motions within one interrogation area, a tracking approach is more suitable.

2.3 PIV processing and data analysis

The raw data sets are imported in Matlab (R2015a; The Mathworks) for further processing. Individual frames are reconstructed per line by conventional envelop detection (using a Hilbert transform) and log compression of the signal; test without compression gave similar results for the mean flow statistics. A single frame of \(4\times 4~\hbox {cm}^2\) is represented by 128 \(\times\) 2432 image elements. Note the large difference in apparent resolution, determined by the transducer element pitch and sampling frequency, respectively.

Displacements are estimated using custom particle image velocimetry software (Poelma et al. 2011). The algorithm allows for iterative analysis with interrogation window deformation. The raw data are processed by cross-correlation of subsequent frames. For the single-phase case, a sliding average is required using three consecutive frames (e.g. 1 + 2 and 2 + 3) to obtain a reliable result. This is related to the low tracer number density, which results from a conservative seeding level, aimed at keeping a low volume fraction of the relatively large tracers. For the two-phase cases, the data quality is sufficient to perform standard correlation using only two frames. This directly results from the fact that the dispersed phase acts as tracer and is abundant. A test using a similar sliding averaging process over three consecutive frames for the two-phase data gave very similar results compared to standard two-frame correlation. This implies that the additional temporal filtering by the sliding average was minimal for the single-phase case. It was therefore decided not to repeat the single-phase experiments with a higher seeding concentration.

Depending on the case, either individual image pairs are analysed or correlation averaging using the entire data set is used. The data sets are typically analysed at \(16\times 128\) pixels with 50 % overlap; equivalent to a spatial resolution of the vector field of \(2.4\times 1.25~\hbox {mm}^2\) (streamwise \(\times\) radial). Note that the thickness of the measurement volume, which governs the out-of-plane resolution, was around 4.5 mm. The resulting vector fields are validated using a conventional median test; outliers are replaced using linear interpolation of the surrounding vectors.

Standard vector validation was not always successful and some outliers remained in the data. This was due to the fact that the small number of outliers (a few percentage) were often clustered, making it difficult to remove them. Therefore, a local histogram analysis was performed: at each position, vectors that had a velocity component that deviated more than three times the local standard deviation from the local mean were excluded.Footnote 2 This removed obvious ‘spikes’ in the time series. Results using different thresholds (2.5 and 3.5 times the standard deviation) were very similar. Visual inspection showed that this pragmatic approach only removed the clear outliers and as such the choice in detection method did not affect the statistics.

The velocities in the large pipe are small compared to the image sweep velocity (here approximately 3.4 m/s, transducer width times image acquisition rate). This means that beam sweep effects, which originate in the fact that vertical scanlines of each frame are recorded sequentially, can be ignored (Zhou et al. 2013). Local velocities therefore directly follow from displacement divided by interframe time, \(\Delta T\). Scaling parameters, separate for x and y direction, are obtained by calibration using two thin wires separated by a known distance. The values were checked using both the wall locations and hardware specifications (transducer pitch).

The resultant vector fields are analysed by applying the standard Reynolds decomposition, \(u = U + u^\prime\). Instantaneous velocities are denoted by u and v for the streamwise and radial velocity components, respectively. U and V represent the mean values and a prime indicates a fluctuating component.

3 Results

The result section is divided into three parts: first, single-phase results are shown for the laminar and turbulent flows. These serve as validation of the measurement system and to demonstrate that UIV is capable of obtaining turbulence statistics. Subsequently, results are reported for a turbid flow at moderate volume load in the large pipe facility and at moderate volume load in the gravity-driven small tube flow. In this facility, we also investigate the feasibility of determining the particle concentration profile. Finally, tests in a mock-up show that velocity fields can be obtained at 10 % volume load; an ad hoc error estimation is also performed on this data set.

3.1 Single-phase flow

Figure 2 shows a typical velocity field in the large pipe flow facility operating at a Reynolds number of Re = 627. The vector field is superimposed on the average ultrasound image to show the wall locations. Also shown (right-hand side) is the average velocity profile. The errorbars, only shown for half of the data points, represent the root-mean-square of the velocity at that radial position and thus serve as an estimate for the uncertainty. As can be seen, the data match the theoretical (parabolic) velocity profile to within the measurement uncertainty. The parabolic profile shown is based on a fit using the data in the range with errorbars. The minor skewness is likely due to remnants of the inlet conditions.

The results for the single-phase turbulent case are shown in Figs. 3 and 4. These statistics have been obtained by averaging 1680 vector fields from four data sets. This is equivalent to a total recording time of approximately 10 s. In Fig. 3, the left-hand side shows an instantaneous velocity field at \(Re\approx 5120\). The vectors represent only the fluctuating velocity field, i.e. the mean velocity profile has been subtracted. Note that only half the transducer width is used here to ensure that the interframe time is small enough. At this Reynolds number the mean centerline displacement in the streamwise direction was approximately 6 pixels and fluctuations in the order of 1 pixel. In contrast, the radial fluctuations are up to 8 pixels; again, this is a consequence of the difference in spatial resolution (or scaling factor) of the ultrasound images, and not due to the flow properties.

The right-hand side of Fig. 3 shows two UIV results for the mean streamwise velocity profile (normalised using the centerline velocity): the squares (\(\square\)) represent the result obtained by averaging instantaneous vector fields. The crosses (\(\times\)) are the result of correlation averaging (Adrian and Westerweel 2010), here performed using interrogation areas that were half the ‘height’ of the regular analysis. While providing a superior resolution, this method cannot provide statistics detailing the fluctuating behaviour (e.g. root-mean-square values). It is reported here merely to check the mean flow profile and investigate the effect of the interrogation area size in the near-wall, high-gradient region.

A wealth of reference data is available from experiments and numerical studies (Eggels et al. 1994; Van Doorne and Westerweel 2007) for turbulent pipe flow in the range of Re = 5300–5600. The bulk velocity for the present data obtained by numerical integration of the velocity profiles is 12.8 cm/s, leading to Re = 5120. This is close to the target value and the value based on the flow meter reading. The maximum velocity is 18.1 cm/s, leading to a \(Re_{c}\) of 7240; this is also in line with the values reported for the data sets used for validation (6950–7350). Generally, a comparison will be based on scaled parameters (e.g. using the wall shear stress, plus units). Unfortunately, pressure drop measurements are not available for all experiments. However, as the experiments are performed in the exact same facility as the reference studies, we can directly compare our results, without the need for such scaling. In Fig. 3 the solid line represents the reference value for the mean velocity profile, normalised with the centerline velocity. The UIV results coincide with the reference profile, apart from the region very close to the wall for the vector-averaged result. The relatively large size of the interrogation area here leads to an overestimation of the velocity, a well-documented issue for PIV studies.

(Left) An instantaneous vector field obtained in the turbulent pipe flow, after subtraction of the mean velocity profile. Colour coding denotes the radial velocity component, v. The dashed lines indicate the pipe walls. (Right) Mean profile of the normalised streamwise velocity component for the turbulent case (Re = 5120). Symbols represent data from the present study (correlation-averaged and conventional averaging), the solid line represents reference data

Figure 4 shows the turbulence statistics: the root-mean-square values of the fluctuating component of the velocities (u-rms, v-rms; \(\langle {uu}\rangle ^{1/2},\,\langle {vv}\rangle ^{1/2}\)) and the Reynolds stress, \(\langle {uv}\rangle\). The streamwise fluctuations are overestimated by approximately 2.6 mm/s in the core, decreasing to an overestimation of 1.5 mm/s near the peak values (in the near-wall region, \(r/D \approx\) 0.45). Note that an error of 2.0 mm/s is equivalent to a displacement error of 0.08 pixels in the streamwise direction (1.5 % of the bulk velocity). The radial fluctuations are captured well. A fluctuating motion in this direction will be lead to a much larger displacement, facilitating the velocity estimation. The radial fluctuations are underestimated in the near-wall region. Here, it is hypothesised that the strong local streamwise gradient starts influencing the estimation of the radial fluctuations.

The general trend of the Reynolds stresses \(\langle {uv}\rangle\) is captured well. The data set may not be large enough to obtain fully converged statistics (a total recording time of 10 s and an estimated integral time scale of 0.3 s suggest only 33 integral time scales are captured), which may explain some of the scatter. A notable feature which persisted in other data sets was the dip around \(r/D = 0.25\). After careful visual inspection of the data, it appears that a single ‘horizontal’ line in the images appeared to contain an artefact. This was apparent as some additional noise, which could partly obscure a tracer particle image passing it. As the noise was not stationary, it could not easily be removed. While the consequence of this imaging artefact was not apparent in the other statistics, it should be noted that even the slightest bias may influence the Reynolds stresses (Christensen 2004).

Based on the data reported in Figs. 3 and 4, it can be concluded that UIV is capable of measuring both mean and fluctuating quantities in a turbulent, single-phase flow. While the technique cannot be expected to outperform conventional methods in single-phase flow, the data nevertheless compare well with reference data.

3.2 Two-phase flow

After the validation of UIV for the single-phase, the tracer particles are flushed out of the system and are replaced with ‘dispersed phase’ particles. To ensure a consistent concentration, the flow rate was increased to the maximum attainable value (approximately 0.5 m/s with the current gearing of the pump) to minimise settling of particles throughout the facility. Experiments were performed by gradually adding more particles, up to a maximum volume fraction (\(\phi\)) of 3 %.

Figure 5 shows the mean velocity (obtained by averaging vector fields, not using correlation averaging) for various cases. As can be seen, the particle-laden cases (\(\phi\) = 1, 2 and 3 %) match the single-phase data and the single-phase reference data, apart from the two points closest to the wall. Note that the experiments at moderate load actually agree better with the reference data (solid line) than the single-phase results (open squares). No clear trend can be discerned for the near-wall deviations, so it is likely that these deviations are due to increased noise levels in the high-gradient region. While the flow appears completely opaque for the particle-laden cases, the dispersed phase apparently still closely matches the carrier phase and the latter is not influenced significantly.

Figure 6 shows the turbulent fluctuations (u-rms, v-rms), again for the single-phase case and for the three particle-laden cases. The general shape is the same for single-phase and particle-laden cases. The particle-laden cases are actually closer to the reference than the single-phase flow UIV data. The likely explanation is the fact that the tracer density is much higher in the particle-laden case (as the dispersed phase is the tracer), so that the measurement errors are reduced; this explanation no longer holds in the near-wall region, where the displacement gradients are likely the largest contributor to the measurement error. For the radial fluctuations (v-rms), it appears that there is a reduction for the case of a volume load of 3 %, but a more detailed analysis will not be given here (see Discussion).

3.3 Small tube experiments

To investigate the performance of UIV in a similar flow, yet at a different scale, a gravity-driven pipe flow was created in a tube with a diameter of 1 cm. Figure 7 shows raw image snapshots and the mean velocity profile for two cases. In the left-hand side, the flow rate is relatively low and the flow is characterised by a parabolic velocity profile. The Reynolds number is around 1500 in this case. The particles form a (mobile) bed and there is an apparent slip velocity at the top of this bed (indicated by the dashed line; see also the region indicated by the rectangle). Figure 8 shows the measured particle velocity profile (together with the local concentration, discussed in the next section). The top part of the velocity profile could not be recovered, as it turned out that the very thin wall of this tube resulted in an image region that was too close to the transducer. Note that each image element (scanline) is actually obtained by combining ‘echoes’ from several transducer elements and this beamforming fails at such short distances.

When the flow rate is increased, the particles remain fully suspended. The figure on the right-hand side shows this case, characterised by a Reynolds number of approximately 6800. In this case, which had a volume fraction of approximately 5 %, the velocity profile resembles a flattened, turbulent profile; see also Fig. 8.

Mean streamwise particle velocity profile for the laminar and turbulent cases and approximate local volume fraction; small tube experiment. The solid lines represent the particle velocity profiles, while the dashed lines represent the local concentration (on the secondary axis). “L” refers to the laminar case, while “T” refers to the turbulent case. The vertical dashed lines indicate the tube walls and the bed height for the laminar case

The image intensity is affected by the amount of scatterers, i.e. the volume fraction of dispersed phase. To test if a quantitative analysis of the local volume fraction was possible, a series of calibration experiments were performed. The gravity-driven flow (fed from a well-stirred reservoir) was documented with increasing volume loads. The flow rate was kept high enough so that the particles appeared to be distributed homogeneously. For each volume load, the mean image intensity (I) was determined by averaging the region within the tube. The single-phase case was quantified and used to subtract the background intensity (\(I_0\)). Figure 9 shows the image intensity as a function of the volume load; the intensities have been normalised using the limiting value at high volume fractions (\(I_{\max }\)). The open circles represent repeated experiments using the same suspension; the squares represent a repeated experiment with newly prepared particle suspensions.

As can be seen in Fig. 9, the intensity monotonically increases with concentration. The results can be described by a fitted function of the form \(a + b(1-\text{e}^{(-\phi /c)})\); \(\phi\) represents the volume fraction. The value of a is close to zero (a = 0.00746), which indicates that the background subtraction using the single-phase case works effectively. The value of b is close to unity (1.019), which is expected due to the normalisation with a limiting maximum value (\(I_{\max }\)). The only non-trivial parameter is c (which here has a value of 2.361), which links the observed intensity to the particle concentration for this specific particle type. Note that the current fit function was chosen in an ad hoc manner. The exact underlying chain of processes (scattering behaviour, data acquisition, conversion of RF signals to intensity images, etc.) will have an effect on the shape of the function. Using this approach, an estimate can be obtained for the local concentration. As the signal appears to saturate around 10 %, the accuracy will rapidly decrease when we approach this value. Nevertheless, it can serve as a semi-quantitative indicator of the particle distribution. This can be seen in Fig. 9, where the estimated concentration profiles for the two cases are shown (on the secondary axis). For the laminar case, there is a steady increase from near-zero to 3 % just above the bed. In the bed, the concentration can no longer be recovered: the intensity approaches the saturation value, leading to an infinite concentration from the fitted function. For the turbulent case, there also is a stratification, with the overall mean concentration around 5 %. This is in agreement with the known suspension properties (i.e. amount of particles added, which was the same for both cases). At the left-hand side, the estimation fails due to the aforementioned beamforming issue. At the bottom of the tube, the concentration again increases to values close to the saturation values. For future studies, this implies that concentration measurements are feasible, as long as the local values are significantly lower than the saturation value.

3.4 Error estimation using time-resolved data

To conclude this study, we estimate the measurement uncertainty at a high load (10 %). As there is no reference data available, we estimate this error in an ad hoc manner: first, a flow is created in a small mock-up, which is essentially a copy of the measurement section, but with capped ends. A flow field is created by gently stirring/shaking the mock-up. Data are then recorded at maximum frame rate, which ensures that the data are resolved with respect to time. The left-hand side of Fig. 10 shows a single snapshot of the flow field. The right-hand side shows two arbitrary traces of the velocity (i.e. velocity as a function of time at two positions). While chaotic, the flow field evolves rather slowly compared to the sampling frequency. The traces thus contain two contributions: (1) the evolving velocity field and (2) measurement noise. The former can be described by a polynomial fit (here we use a 5th-order polynomial). The difference between this polynomial fit and the instantaneous data then provides an estimate for the noise. This approach assumes that the high-frequency contributions are noise and not flow features. In the figure, the solid curve represents the fit, while the dashed lines represent the root-mean-square of the difference between the signal and the fit. Applying this process to the entire vector field, we obtain a standard deviation of 3.5 mm/s in the streamwise (x) direction and 0.516 mm/s in the radial (r or y) direction. The factor seven difference is again a direct consequence of the difference in spatial resolution (or scaling factor). Translating this to the earlier turbulent pipe flow experiment, these errors correspond to 1.9 and 0.3 % of the centerline velocity. Naturally, this ignores the fact that in PIV the measurement error may be affected by the magnitude of the displacement and gradients. Nevertheless, these error estimates are comparable with the overestimationFootnote 3 of the values for u-rms and v-rms, as reported in Fig. 4.

4 Discussion

In Sect. 3.1, we demonstrated that UIV is capable of accurately obtaining turbulence statistics in a single-phase flow. This validation was feasible, as there is a wealth of data available for fully developed turbulent pipe flow at this Reynolds number. For the two-phase flow, this approach is no longer possible. To the best of our knowledge, there is no data for the flows with moderate volume fraction. However, as the particles are relatively small and the volume fraction is only moderate, it can be expected that the two-phase statistics will resemble the single-phase flow results. This is indeed what we observe: the data shown in Figs. 5 and 6 closely match for single-phase and the particle-laden cases. While this may be disappointing from a fluid mechanics point of view, it inspires confidence in the measurement technique. The ad hoc error estimation also confirms that the measurement errors are small enough to obtain insight in flow phenomena in future studies.

As stated earlier, we do not attempt to interpret the two-phase results. This is in part due to shortcomings in the facility and materials that only became apparent afterwards. In particular, the polydispersity of the particles turned out to be somewhat larger than expected. As the large pipe facility was not designed for two-phase experiments, the largest fraction of the particles may have settle in dead zones during the experiments. Therefore, it can be that the composition of the suspension and effective volume fraction changed somewhat over time. Note that the test in the mock-up at volume fractions up to 10 % did not suffer from this effect. While this does not invalidate the main contribution of this study, it limits a comparison between the particle-laden cases. On a related note, we noticed that a small fraction of relatively large particles formed a thin bed along the bottom wall, even though the bulk of the particles was suspended by the flow. The effect from these unexpectedly large particles may also explain the underestimation of the flow statistics near the bottom wall (Fig. 6).

4.1 UIV limitations

The focus of this study is to demonstrate the feasibility of performing UIV in flows with moderate volume loads. While we demonstrate that this is indeed feasible, a number of issues remain that require attention.

The thickness of the measurement volume is relatively large. The estimate of 4.5 mm at the centerline indicates that there will be some averaging in the ‘out-of-plane’ direction, due to the acoustic lens. While we did not observe any such effects in the large (4-cm) pipe, they will become more prominent when smaller diameter tubes will be studied. Furthermore, the thickness of the measurement volume becomes larger away from the transducer, which may lead to asymmetric profiles due to increasing averaging effects.

Currently, UIV only provides the velocity field of the dispersed/particle phase. While in the present case the particle velocities closely matched the fluid velocities, for future studies it may be desirable to device a method to (also) obtain fluid velocities. This could be achieved by using, e.g. contrast bubbles to seed the fluid phase and choose a dispersed phase that is acoustically silent. Such an approach could be assisted by a post-processing filtering approach (e.g. isolate the nonlinear response of the contrast bubbles from the sound reflected from other scattering objects). This would be equivalent to the use of fluorescent tracer particles and cut-off filters in optical PIV (Poelma et al. 2006).

The maximum achievable imaging rate of ultrasound systems is limited, which effectively creates an upper limit on the flow velocities that can be measured (in practice 0.5–1 m/s). This also hinders the extension to larger scale flows, as the imaging rate decreases in proportion to the image depth: for larger depths, the maximum measurable velocity is lower (Poelma et al. 2012). While recent work has shown that there are ways to overcome this limitation, they have drawbacks. The interleaved approach (Poelma and Fraser 2013) requires complex acquisition protocols only achievable with specialised, research-oriented ultrasound systems. Most commercially available systems do not provide access at this level. An alternative approach, plane-wave imaging (Leow et al. 2015), requires similarly complex acquisition methods and also high-bandwidth electronics. For the standard approach (as used here), experiments have to be designed with the upper limit for the velocity in mind.

5 Conclusion and outlook

In this study, we demonstrated that it is feasible to perform accurate velocity measurement in complex flows with moderate volume fractions using ultrasound imaging velocimetry. The single-phase case could be validated based on the literature data, but this was impossible for the two-phase cases. Nevertheless, an ad hoc error estimation suggests that the method is accurate enough to allow detailed studies in the field of particle–fluid interactions. As demonstrated here, UIV is capable of obtaining turbulence statistics in particle-laden flows that are inaccessible using optical techniques; while not as accurate as optical PIV, UIV can obtain data in suspension with a volume fraction that is more than an order of magnitude higher than the limits for optical techniques. In future work, we will apply the techniques outlined here for a systematic study of particle-laden flows. With the present techniques, it will be possible to validate, for instance, the recent work on densely laden channel flows (Picano et al. 2015; Shao et al. 2012). A wide range of other applications, such as sediment transport or dune/ripple formation is within reach. Going beyond solid particles, studies in alternative systems such as oil/water emulsions may also be feasible. While future developments will bring further improvements, UIV in its currently state it is already a powerful tool for the multiphase community.

Notes

In practice, this implies a translation of approximately 2 cm between the two systems when considering the bottom half of the pipe.

By ‘local’, we here imply the time-averaged statistics at the position of the vector under consideration.

Assuming that the measurement error \(\epsilon\) is uncorrelated to the measured value, the measured value of the fluctuations is the sum of the true value and the measurement error: \(\langle {uu}\rangle _\text{meas.} = \langle {uu}\rangle _\text{true} + \epsilon ^2\).

References

Adrian RJ, Westerweel J (2010) Particle image velocimetry. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Beulen B, Bijnens N, Rutten M, Brands P, van de Vosse F (2010) Perpendicular ultrasound velocity measurement by 2d cross correlation of rf data. Part a: validation in a straight tube. Exp Fluids 49(5):1177–1186

Christensen KT (2004) The influence of peak-locking errors on turbulence statistics computed from piv ensembles. Exp Fluids 36(3):484–497

Deen NG, Westerweel J, Delnoij E (2002) Two-phase piv in bubbly flows: status and trends. Chem Eng Technol 25(1):97

Eggels JGM, Unger F, Weiss MH, Westerweel J, Adrian RJ, Friedrich R, Nieuwstadt FTM (1994) Fully developed turbulent pipe flow: a comparison between direct numerical simulation and experiment. J Fluid Mech 268:175–210

Elkins CJ, Alley MT, Saetran L, Eaton JK (2009) Three-dimensional magnetic resonance velocimetry measurements of turbulence quantities in complex flow. Exp Fluids 46(2):285–296

Heindel TJ (2011) A review of x-ray flow visualization with applications to multiphase flows. J Fluids Eng 133(7):074001

Hof B, van Doorne CWH, Westerweel J, Nieuwstadt FTM, Faisst H, Eckhardt B, Wedin H, Kerswell RR, Waleffe F (2004) Experimental observation of nonlinear traveling waves in turbulent pipe flow. Science 305(5690):1594–1598

Jamison RA, Siu KK, Dubsky S, Armitage JA, Fouras A (2012) X-ray velocimetry within the ex vivo carotid artery. J Synchrotron Radiat 19(Pt 6):1050–1055

Jullien P, Lemonnier H (2012) On the validation of magnetic resonance velocimetry in single-phase turbulent pipe flows. J Magn Reson 216:101–106

Kim HB, Hertzberg JR, Shandas R (2004) Development and validation of echo PIV. Exp Fluids 36(3):455–462

Kim H-B, Hertzberg J, Lanning C, Shandas R (2004) Noninvasive measurement of steady and pulsating velocity profiles and shear rates in arteries using echo piv: in vitro validation studies. Ann Biomed Eng 32(8):1067–1076

Leow CH, Bazigou E, Eckersley RJ, Alfred CH, Weinberg PD, Tang M-X (2015) Flow velocity mapping using contrast enhanced high-frame-rate plane wave ultrasound and image tracking: methods and initial in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Ultrasound Med Biol 41(11):2913–2925

Linne MA, Paciaroni M, Berrocal E, Sedarsky D (2009) Ballistic imaging of liquid breakup processes in dense sprays. Proc Combust Inst 32(2):2147–2161

Patil AV, Peters EAJF, Sutkar VS, Deen NG, Kuipers JAM (2015) A study of heat transfer in fluidized beds using an integrated dia/piv/ir technique. Chem Eng J 259:90–106

Picano F, Breugem W-P, Brandt L (2015) Turbulent channel flow of dense suspensions of neutrally buoyant spheres. J Fluid Mech 764:463–487

Poelma C, Westerweel J, Ooms G (2006) Turbulence statistics from optical whole-field measurements in particle-laden turbulence. Exp Fluids 40(3):347–363

Poelma C, Mari JM, Foin N, Tang MX, Krams R, Caro CG, Weinberg PD, Westerweel J (2011b) 3d flow reconstruction using ultrasound PIV. Exp Fluids 50(4):777–785

Poelma C, van der Mijle RME, Mari JM, Tang M-X, Weinberg PD, Westerweel J (2012) Ultrasound imaging velocimetry: toward reliable wall shear stress measurements. Eur J Mech B Fluids 35:70–75

Poelma C, Fraser KH (2013) Enhancing the dynamic range of ultrasound imaging velocimetry using interleaved imaging. Meas Sci Technol 24(11):115701

Scarano F, Poelma C (2009) Three-dimensional vorticity patterns of cylinder wakes. Exp Fluids 47(1):69–83

Shao X, Tenghu W, Zhaosheng Y (2012) Fully resolved numerical simulation of particle-laden turbulent flow in a horizontal channel at a low reynolds number. J Fluid Mech 693:319–344

Trip R, Kuik DJ, Westerweel J, Poelma C (2012) An experimental study of transitional pulsatile pipe flow. Phys Fluids 24(1):014103–014103

Tropea C, Yarin AL, Foss JF (2007) Springer handbook of experimental fluid mechanics, vol 1. Springer, Berlin

Van Doorne CWH, Westerweel J (2007) Measurement of laminar, transitional and turbulent pipe flow using stereoscopic-piv. Exp Fluids 42(2):259–279

Van Ooij P, Guédon A, Poelma C, Schneiders J, Rutten MCM, Marquering HA, Majoie CB, Vanbavel E, Nederveen AJ (2011) Complex flow patterns in a real-size intracranial aneurysm phantom: phase contrast MRI compared with particle image velocimetry and computational fluid dynamics. NMR Biomed 25(1):14–26

Walker AM, Scott J, Rival DE, Johnston CR (2014) In vitro post-stenotic flow quantification and validation using echo particle image velocimetry (echo piv). Exp Fluids 55(10):1–16

Wiederseiner S, Andreini N, Epely-Chauvin G, Ancey C (2011) Refractive-index and density matching in concentrated particle suspensions: a review. Exp Fluids 50(5):1183–1206

Zhou B, Fraser KH, Poelma C, Mari J-M, Eckersley RJ, Weinberg PD, Tang M-X (2013) Ultrasound imaging velocimetry: effect of beam sweeping on velocity estimation. Ultrasound Med Biol 39(9):1672–1681

Acknowledgments

We thank prof. Jerry Westerweel (TU Delft) for providing the reference PIV and DNS data for the single-phase turbulent pipe flow and Carlos Walker-Ravenna for assisting in the measurements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Gurung, A., Poelma, C. Measurement of turbulence statistics in single-phase and two-phase flows using ultrasound imaging velocimetry. Exp Fluids 57, 171 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00348-016-2266-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00348-016-2266-x