Abstract

Ultrasound particle image velocimetry (PIV) can be used to obtain velocity fields in non-transparent geometries and/or fluids. In the current study, we use this technique to document the flow in a curved tube, using ultrasound contrast bubbles as flow tracer particles. The performance of the technique is first tested in a straight tube, with both steady laminar and pulsatile flows. Both experiments confirm that the technique is capable of reliable measurements. A number of adaptations are introduced that improve the accuracy and applicability of ultrasound PIV. Firstly, due to the method of ultrasound image acquisition, a correction is required for the estimation of velocities from tracer displacements. This correction accounts for the fact that columns in the image are recorded at slightly different instances. The second improvement uses a slice-by-slice scanning approach to obtain three-dimensional velocity data. This approach is here demonstrated in a strongly curved tube. The resulting flow profiles and wall shear stress distribution shows a distinct asymmetry. To meaningfully interpret these three-dimensional results, knowledge of the measurement thickness is required. Our third contribution is a method to determine this quantity, using the correlation peak heights. The latter method can also provide the third (out-of-plane) component if the measurement thickness is known, so that all three velocity components are available using a single probe.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

An important factor limiting the use of particle image velocimetry (PIV) is the need for optical access. In recent years, a number of studies have shown that it is possible to replace the conventional imaging system (viz. camera, lenses and lasers) with an ultrasound imaging system (Gharib and Beizaie 2003, Kim et al. 2004, Liu et al. 2008). In ultrasound imaging, or echography, an image is constructed by emitting sound waves and interpreting the received echoes, which originate in changes in the local acoustic impedance of the material. As ultrasound can penetrate optically opaque materials, measurements can be obtained in flows that fail the strict optical access requirements. Recent years have seen an increase in resolution (by utilizing higher ultrasound frequencies), but also in framing rates. Possible applications range from in vivo blood flow measurements (Sengupta et al. 2007, Hong et al. 2008) to in vitro measurements in complex, non-transparent geometries and/or fluids (Zheng et al. 2006, Wang and Shandas 2007). Note that this technique should not be confused with Doppler ultrasound velocimetry, which utilizes the frequency shift of moving scatterers to determine flow velocities. The latter method, widely used in biomedical applications, can only provide the velocity component aligned with the sound propagation direction.

1.1 Scope of this study

The main concept of applying PIV to ultrasound images has already been shown in the papers mentioned in the introduction. In the current study, we build on these results and present three new concepts that improve the accuracy and scope of the method. These results originate in the subtle differences that complicate a direct application of PIV to ultrasound images: for instance, images are not recorded simultaneously, but rather as a line-by-line sweep. This means that a correction is needed when one relies on spatial correlation to estimate velocities. This correction is described in Section 2. The second extension of the technique describes the use of ultrasound PIV to document complex three-dimensional flows by scanning a volume (Section 4.2). This will also provide a distribution of the wall shear stress, after reconstructing the geometry. The 3D approach is only meaningful if the thickness of the measurement plane is known. We present a method to estimate this thickness in Section 4.4. An additional advantage of the latter analysis is that it presents a new method to measure all three velocity components from a single linear probe. Besides these three new concepts, we also present a brief accuracy assessment and a demonstration of the technique in transient flows (Sections 4.1 and 4.3).

In this study, we will not look at other differences in the imaging methodology. Examples of the latter include the fact that the intrinsic image resolution is different for lines and columns of the image. In the case of a standard linear array probe, the number of columns (or A-lines) in the raw image is determined by the number of piezoelectric elements that are used and the number of different weighting combinations used to transmit during an image recording. The information along each of these columns is constructed by evaluation of the received radiofrequency (RF) data (e.g., associating time-of-flight with a particular depth). The resolution in this ‘column’ direction is thus determined by the wavelength of the ultrasound—which generally leads to higher resolutions than in the ‘line’ direction. Usually, the RF data are down-sampled in such a way that the image presented to the operator is more or less in the proper aspect ratio and with a usable contrast—usually by envelope detection and log compression. To limit the scope, only these ‘B-mode’ images will be used here, even though RF data contain significantly more information.

2 Sweep correction

In conventional PIV, the local velocity is determined by dividing the displacement (usually obtained from the correlation peak location) by the temporal separation between the two images, ΔT. In the case of ultrasound PIV, this ΔT is not only dependent on the framing rate, but also a function of the ‘horizontal’ displacement (i.e., across columns—we here refer to horizontal and vertical for simplicity, which refers to the directions aligned and perpendicular to a linear probe) due to the fact that the image is constructed by a sweep. Footnote 1 The horizontal velocity (U x ) at a certain location is given by the ratio of the pixel displacement (Δx) and temporal separation:

with M a scaling parameter (the magnification in conventional PIV). The temporal separation is the inverse of the frame rate, corrected with the temporal shift as a result of the sweep. The sweep speed can be calculated from the number of columns in the images multiplied by the frame rate (f). In the present case, this gives a sweep speed γ = 550 pixels × 74 Hz ≈ 40,000 pixels/s—this means that the difference between two columns is 1/40,000 s. We have assumed here that there is no ‘dead time’ between sweeps. This has been confirmed by plotting the reciprocal of the frame rate as a function of the number of lines used. The value of the intercept with the vertical (time) axis was negligible, indicating little ‘dead time’. The temporal separation is therefore

For the horizontal velocity, we thus find:

Note that the sign (i.e., direction) of Δx is relevant (e.g., the left-hand side of the image is obtained before the right-hand side, which introduces an asymmetry in the correction). For a typical displacement of 10 pixels, the correction in the horizontal velocity is only 1.8% for the present system. For 20 pixels displacement, it increases to 3.7%. For slower sweep speeds and/or large images, the correction can become more significant. Note that the ‘vertical’ velocity (i.e., across lines) does not need such a correction, as columns are recorded nearly instantaneously.

3 Experimental techniques

For the experiments, flexible tubes (inner diameter 8 mm) are submerged in a water tank and connected by tubing to a centrifugal pump to form a closed flow loop, controlled by a rotameter. Experiments are performed with a fixed flow rate, typically of 75 cm3/min. This results in a maximum velocity of 5 cm/s; the resulting Reynolds number is 200. Flow in both a straight tube (for validation purposes) and the curved tubes are studied. For the latter, the radius of curvature, R c, is approximately 6 cm, so that the Dean number is moderate: De = Re (R/R c)1/2 = 52. Before the bend, the tube is straight for at least 15–20 diameters, so that a laminar flow profile can be expected as inlet conditions. Experiments are performed in (non-transparent) latex tubes and in Sylgard\(^{\circledR}\) tubes. While the latter are transparent, in future studies, they will form the substrate for cell cultures, which will likely decrease the optical clarity. A photograph of a part of the experimental set-up is shown in Fig. 1, which also shows the coordinate system used.

Data are obtained using a commercial Ultrasonix RP500 ultrasound system using a linear transducer (L14-38Footnote 2) operating at 10 MHz (framing rate 74 Hz using all transducer elements). A single focus was placed at the center of the tube, at approximately 4 cm from the transducer. In standard operating mode, the raw RF signals are processed to produce grey-value images of 550 by 357 pixels. The working fluid is water; SonoVue\(^{\circledR}\) contrast agent is added as tracer material (1–10 μm coated SF 6 micro-bubbles), 1 ml is used for a total system volume of approximately 5 l). For details about this contrast agent, we refer to Greis (2004). The rise velocity of the bubbles is negligible.

For one velocity measurement a sequence of at least 256 images is recorded; these will be evaluated sequentially (e.g., correlating image 1 with 2, 2 with 3, etc.). Using a translation stage, the volume containing the curved tube is scanned in the z-direction in slices separated by 0.5 mm, so that in-plane velocities in the entire tube are available (see Fig. 1 for the coordinate system used; note that the transducer is placed in the radial direction). The data are processed using a correlation-averaging multi-pass PIV algorithm (Poelma et al. 2008, 2009) Before processing, the images are masked to remove spurious echoes outside the region of interest. The resolution of the velocity results is 0.5 mm (corresponding to a final interrogation area size of 16 × 16 pixels with 50% overlap) and a field-of-view of 4 × 2.5 × 2.0 cm3. Outliers are removed using the normalized median test (Westerweel and Scarano 2005); the percentage of outliers is less than 1% due to the averaging process. Generally, outliers are only found near bright spots (i.e., strong reflections) that saturate the image. For visualization using isosurfaces, the data are processed with a local 3 × 3 × 3 linear least-square fit of each of the velocity components to further reduce the noise levels.

4 Results

A number of experiments were performed to evaluate the performance of ultrasound PIV in terms of standard PIV parameters (e.g., time delay between successive frames, out-of-plane motion, in-plane gradients, data pre-processing). No significant differences were found between the results from experiments in latex and Sylgard\(^{\circledR}\) tubes.

4.1 Error estimate

The measurement error can be evaluated by studying the standard deviation of the velocity along the centerline of the flow in a straight tube (without vector post-processing). As the flow is expected to be laminar and fully developed, the value of the measured centerline velocity should be constant. Figure 2 shows the convergence of the correlation averaging process: the absolute error in the streamwise displacement is shown for three consecutive iterations (all using 16 × 16 interrogation areas). The error drops to a limiting value of 0.07 pixel in the displacement, which corresponds to a relative error of 0.73% based on the mean velocity (see secondary axis). Further iterations or alternative evaluation schemes, e.g., by varying the window size or applying image pre-processing, did not improve the results. In theory, the measurement error is expected to decrease further if more image pairs are used in the ensemble averaging process. However, this also leads to an increase in measurement time: at a certain point, even the smallest variations or drift in the actual flow rate will cause a noise plateau. The error in the radial direction, evaluated in the same manner was found to be approximately 30% smaller than the streamwise error. However, one has to be careful when comparing these two results: as the radial direction has zero mean displacement, systematic errors cannot be evaluated.

Evolution of the error (absolute in pixels and relative to the mean velocity) as a function of the number of image pairs used for correlation averaging; three consecutive iterations at 16 × 16 pixels. The error is estimated by calculating the standard deviation of the velocity along the centerline (indicated by the red region in the inset; note that this only shows a small portion of the data)

Allowing for a maximal error of 5%, it follows from the graph that at the current imaging conditions we need at least five consecutive frames for an acceptable result. This corresponds to a temporal resolution of 5 × 1/74 ≈70 ms if transient phenomena are studied. This means that e.g., physiologically relevant pulsatile flows (1–2 Hz) can be documented with 15 samples per second. All faster events will be lost in the averaging process. Footnote 3 Note that with updated hardware or a reduced image size (i.e., number of elements used), the acquisition rate can readily be increased.

In Table 1, the influence of the temporal separation ΔT on the measurement error is shown. The mean pixel displacement obviously increases linearly with ΔT. The absolute measurement error (the standard deviation of the axial velocity) increases with this larger mean displacement. The relative error, however, increases only slightly to 0.7%; note that this is a different data set than the data presented in Fig. 2, which has a higher measurement error. It has to be taken into account that this is a laminar flow without out-of-plane motion. Using window deformation, tracer particle loss-of-pair is negligible. The only practical limit is the displacement when compared to the measurement domain size.

4.2 3D Results for the curved tube

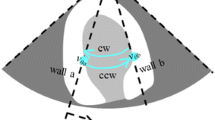

Figure 3 shows the data obtained using an streamwise alignment of the linear transducer (i.e., the transducer is aligned with the x-axis and the mean flow direction; α = 0°). The top figure shows a single B-mode snapshot taken in the mid-plane of the geometry. The middle figure shows the corresponding average velocity vector plot (using 256 images); note that only 25% of the vectors are shown for clarity. The bottom figure shows the reconstructed geometry (as an isosurface using 1/5th of the centerline velocity) and a number of cross-sectional contour plots of the axial velocity. In the latter, a characteristic horseshoe pattern can be seen, indicative of the secondary flow patterns (i.e., ‘Dean vortices’).

(Top) Single B-mode image showing the flow in the latex tube, (Middle) average velocity field at the mid-plane (for clarity, only every second vector is shown; false colours represents the velocity magnitude), (Bottom) Three-dimensional reconstruction of the flow through the tube. Note that the cross-sectional slices shown in the bottom figure are taken in the Cartesian measurement coordinate system

In Fig. 4 (top), velocity profiles are shown at four locations using a polar coordinate system (with respect to the center of rotation of the geometry). The locations are expressed as the angle β with respect to the vertical (y) axis. The development of the secondary flow—resulting in a skewness of the flow profile—can clearly be observed. The field-of-view is unfortunately too small to study the full evolution from a Poiseuille profile to a fully developed Dean profile.

(Top) Velocity profiles at four positions (described by the angle with respect to the vertical axis, β). The results for β = −1°, 11° and 20° are shown with an offset of, respectively, 0.05, 0.10 and 0.15 m/s for clarity. (Bottom) Cross-sections at β = −5 and 20° (the latter with an off-set of 10 mm to the right): shown are isocontours (equidistantly spaced at intervals of 0.005 cm/s) and the wall shear stress obtained from polynomial fits (as colour coding). The equivalent WSS for Poiseuille flow is indicated by the arrow. Note that the y-axis of the bottom figure is in this case aligned with the line intersecting the center-of-radius and the middle of the tube

In Fig. 4 (bottom), two cross-sections are shown with the wall shear stress distribution derived from the velocity data. The wall shear stress is obtained by fitting a polynomial function to the near-wall data and subsequently finding the zero crossing (which corresponds to the location of the wall) and the gradients at the wall. A detailed explanation and validation of this method is given in Poelma et al. (2009). The method processes one cross-section at a time: data are extracted from the data set at an initial seed point. A polynomial fit is then performed to find the wall location (which provides one ‘slice’ of the geometry). Finally, based on the mean direction of the flow in the slice, the algorithm proceeds to a downstream location and the process is repeated.

The asymmetry in the distribution of the wall shear stress can clearly be seen in Fig. 4, with the downstream cross-section being more asymmetric, as expected. The corresponding wall shear stress for a Poiseuille flow (with the same flow rate) is approximately 28 mPa, so the outer wall experiences a significantly higher tangential force due to the curvature. It should be noted that only two velocity components are available for the calculation of the wall shear stress. Close to the wall, the gradients are dominated by the axial velocity components, so the error due to neglecting the missing out-of-plane component is small.

The flow rate in the curved tube can be obtained by integrating a cross-sectional streamwise velocity distribution. When this is done for a number of angles β, we find variations of 2–3% between planes and a mean value of 78.7 cm3/min, which agrees well with the 75 cm3/min of the rotameter; the difference can most likely be explained by the uncertainty of the latter (estimated at 2.5% full scale, corresponding to 5 cm3/min).

4.3 Transient flows

To test the performance of the measurement technique on a transient flow in a straight tube, a periodic flow was created by periodically pinching the entrance tube (while the pump provided a constant pressure gradient). Data are obtained in the center plane, with the transducer in the streamwise position. In this case, a sliding moving average over 8 frames is used for the processing (with 50% overlap). This means that frames 1–8 are averaged to calculate one flow field, followed by an average over frames 5–12, etc. The resulting temporal resolution in this case, with a acquisition rate of 119 Hz, is 34 ms. In Fig. 5, the resulting centerline velocity of the pulsating flow is shown. Note that there is a net transport, as the mean velocity is slightly negative—the latter resulting from a mirrored probe position. The cycle length T is 0.67 s. Also shown are the corresponding instantaneous axial velocity profiles (only one third of the profiles shown for clarity).

Centerline velocity of the pulsating flow. Also shown are the corresponding velocity profiles for a number of instances. For the latter the horizontal location of the profile indicates the time at which the data is obtained, while the vertical scale and vector length are in arbitrary units. The negative sign of the mean flow results from a 180° rotation of the transducer in this experiment

The velocity profiles can be compared with the theoretical Womersley profiles (McDonald 1974), see also the “Appendix” for a summary of the theoretical prediction. The Womersley number (α) is given by

In this definition, R represents the tube diameter, ω is the angular frequency and ν is the kinematic viscosity. T is the cycle duration, equal to 2π/ω. For the present experiment, α = 11.5, which means that the transient inertial forces can be expected to play a significant role, leading to a flat core flow and a phase shift with the viscosity-dominated boundary layer. In Fig. 6, three instantaneous velocity profiles at different stages during the cycle are shown (markers), together with the corresponding theoretical predictions (dashed lines). The phase angle τ for each case is given by τ = t/T (mod 1). Note that in the current case, the theoretical prediction is composed of a Womersley profile and a steady (Poiseuille) contribution. The contribution of the latter can easily be determined by calculating the time-averaged flow profile. The only parameter that has been adjusted is the amplitude of the Womersley profile, so that the peak flow of the prediction matches that of the experiment. As can be seen in the figure, there is a reasonably good agreement between experiments and theory. Note that the theoretical results are based on a perfect harmonic driving force, while this was likely not the case for the experiments.

The techniques of 3D reconstruction from slices can be applied on transient flows as well. In the case of turbulent flows, only the mean flow pattern can be recovered. If the flow is quasi-steady (e.g., a pulsatile flow with moderate Reynolds number), the transient behavior can also be obtained. This requires a trigger signal to phase-lock the measurements, which was not available in the current facility. Alternatively, the phase information can be reconstructed a posteriori from the velocity fields in some cases, see e.g., Poelma et al. (2008).

4.4 Measurement volume thickness

For a meaningful interpretation of the results, it is necessary to know the thickness of the measurement volume (equivalent to the light sheet thickness in conventional PIV). This can in theory be measured by, e.g., traversing a needle hydrophone or by applying Schlieren methods. Here, we present an alternative method based on the height of the correlation peaks.

The normalized correlation peak height (P) is proportional to tracer particle number density, in-plane and out-of-plane loss fractions and loss due to gradients (Westerweel 1997, 2008):

As we are using ensemble averaging, N I ′ is actually the product of N I (the tracer particle number density of a single image) and the total number of realizations. The use of iterative window-shifting/deformation ensure that the values of F I and F Δ approach unity, as no tracer particle images are ‘lost’ in the correlation process (note that in the middle of the tube there are hardly any gradients to begin with). Therefore, the peak height is only a function of tracer particle number density and out-of-plane losses:

If the transducer is placed in a streamwise orientation (the transducer is aligned with the central (x) axis of the tube), we can expect no out-of-plane loss-of-pair in a straight tube: there is no radial motion. If we subsequently rotate the transducer 90° to a radial orientation (α = 90°, transducer aligned with the z axis; see Fig. 1), while keeping the tracer particle concentration (and number of images) constant, we can determine the value of F o for this case:

with the subscripts ‘R’ and ‘S’ denoting the cases with radial and streamwise transducer orientation. The out-of-plane loss of pair can thus be calculated by the local peak height (available at each interrogation location), divided by the (mean) peak height of the streamwise case. For a ‘top hat’ measurement volume Footnote 4, the expression for the out-of-plane loss of pair fraction is given by:

with δ the thickness of the volume. F o is zero for large displacements. The local velocity U = Δz/ΔT can thus be found from

Either the thickness of the measurement volume or the flow velocity needs to be known to be able to calculate the other. In the present experiment, the reference velocity profile is available from the ‘streamwise’ case. Using a least-squares fit, a thickness of 1.8 mm for the effective measurement volume thickness can be obtained. The step-size of 0.5 mm used for the scanning measurement shown in Fig. 3, which was chosen to match the in-plane resolution, thus leads to an 72% overlap in the z-direction, somewhat higher than the 50% overlap used in the in-plane directions. Note that we have implicitly assumed that the measurement volume is a rectangular box. Due to the nature of image formation, the thickness of the measurement volume will change as a function of distance to the probe (which also occurs in conventional light sheet optics). This change is expected to be small over the diameter of the tube.

4.5 Reconstruction of the out-of-plane component

Once the thickness of the measurement volume is known, the approach can be reversed: the out-of-plane velocity can be reconstructed from the peak height ratios. An example of this method is shown in Fig. 7. This figure shows a contour plot of the reconstructed axial velocity in a Poiseuille flow. The reference centerline velocity obtained from the actual axial measurement was 4.3 cm/s. To evaluate the reconstruction accuracy, we compare the differences between the reconstruction and the theoretical values. We do this by fitting a 2D parabola, V = V max(1 − (r/R)2), and evaluating the residuals. The standard deviation of the discrepancy between fitted and reconstructed out-of-plane velocities was found to be 4%. Note that only the central region was used in this fit (by selecting values above 25% of the maximum velocity). Near the edges, the error increases significantly due to the fact that wall reflections affect the noise level and thus invalidate the out-of-plane reconstruction procedure. The fact that the reconstructed flow is axisymmetric also provides experimental evidence that the thickness of the volume does not change drastically. If the latter would be the case, the reconstruction would be stretched in one direction (due to the fact that δ in Eq. 9 would then vary with radial distance).

With a known thickness of the measurement volume, the out-of-plane velocity can thus be obtained in at least a qualitative manner from the correlation peak heights, while the in-plane velocities follow from the conventional cross-correlation method (they are negligible in Fig. 7 and thus not shown). A single recording with a linear probe can thus provide insight in all three velocity components in a plane. A single additional reference measurement in an orthogonal plane is the only requirement. The only drawback is that the direction of the out-of-plane component cannot be recovered in this way.

The current approach is similar to the study by Raffel et al. (1995), where the absolute value of the normalized correlation peak height was used to reconstruct the out-of-plane component. In our approach, we look at the ratio of the peak with respect to a reference to eliminate effects of noise, tracer number density, etc. A mathematical background is provided by Raffel et al. (1996), a study that focuses on an application using two parallel measurements (three recordings, one of them in a light sheet that is slightly displaced)—the theoretical description can directly be translated to the current approach.

5 Conclusions

In the current work, we have introduced some extension to the capabilities of ultrasound particle image velocimetry. Due to the nature of image acquisition, a (small) correction is needed to estimate the local velocity from the tracer particle displacement. We demonstrate that reliable measurements are possible by evaluating a known test case: Poiseuille flow. Errors of the order of 0.5–1.5% are attainable by means of correlation averaging using 255 image pairs. This error level is comparable to conventional implementations of PIV, yet without the requirement of optical access to the geometry. As the measurement error converges rapidly, even with only a few images acceptable results can be obtained. This means that the current generation of hardware is suitable to study transient flows with a temporal resolution on the order of 1/40 s. The latter assumes a full-size image; the frame rate can be increased by, among others, decreasing the number of transducer elements used. We report instantaneous velocity profiles obtained in a pulsatile flow that correspond reasonably well with the theoretical expectations.

We show that the technique can be extended to document the flow in a volume by scanning the geometry slice-by-slice. The latter approach is straightforward for steady flows, but requires phase-locking for periodic flows—either with an external trigger signal or using an a posteriori analysis. The 3D reconstruction method is used to document the flow in a strongly curved tube. From the velocity data obtained in this geometry, the wall shear stress distribution can be derived. As expected, this distribution shows a clear asymmetry due to the presence of secondary flow patterns.

Finally, we evaluate the thickness of the measurement volume by means of two orthogonal recordings. By evaluating the peak height, the ratio of out-of-plane displacement and measurement volume thickness can be determined. Once one of the two is known, the other can be derived. In the present case, we derive a measurement volume thickness of 1.8 mm. This is associated with a reconstructed flow field that closely resembles the expect parabolic flow pattern. In principle, it is thus possible to obtain all three velocity components using a single recording with a linear probe.

The results presented in this study confirm that ultrasound PIV can provide reliable, detailed information in complex geometries without requiring optical access. This makes it a suitable tool for planned future work correlating endothelial cell response and local flow patterns. Obviously, the technique can also be applied directly to other flow studies that lack optical access.

Notes

This is similar to early implementations of PIV using a scanning laser beam, see e.g., Westerweel et al. (1996).

The L14-38 is a linear array of 128 elements. The center frequency is 9.5 MHz, bandwidth is 9 MHz. Radius is 0 (no geometric focusing). The pitch of the probe is 300 μm.

For periodic flows, the flow cycle can be reconstructed based on ‘a posteriori’ phase-locking, see e.g., Poelma et al. (2008).

For simplicity we have here chosen to describe the measurement volume using a top-hat profile with an effective thickness δ. Alternatively, one could find similar dimensions using e.g., a Gaussian profile as is common in light sheet-based PIV.

References

Gharib M, Beizaie M (2003) Correlation between negative near-wall shear stress in human aorta and various stages of congestive heart failure. Ann Biomed Eng 31(6):678–685

Greis C (2004) Technology overview: SonoVue(Bracco, Milan). Eur Radiol 14:11–15

Hong G, Pedrizzetti G, Tonti G, Li P, Wei Z, Kim J, Baweja A, Liu S, Chung N, Houle H et al (2008) Characterization and quantification of vortex flow in the human left ventricle by contrast echocardiography using vector particle image velocimetry. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 1(6):705–717

Kim H, Hertzberg J, Shandas R (2004) Development and validation of echo PIV. Exp Fluids 36(3):455–462

Liu L, Zheng H, Williams L, Zhang F, Wang R, Hertzberg J, Shandas R (2008) Development of a custom-designed echo particle image velocimetry system for multi-component hemodynamic measurements: system characterization and initial experimental results. Phys Med Biol 53(5):1397–1412

McDonald D (1974) Blood Flow in Arteries. Edward Arnold

Poelma C, Vennemann P, Lindken R, Westerweel J (2008) In vivo blood flow and wall shear stress measurements in the vitelline network. Exp Fluids 45(4):703–713

Poelma C, Van der Heiden K, Hierck B, Poelmann R and Westerweel, J (2009) Measurements of the wall shear stress distribution in the outflow tract of an embryonic chicken heart. J R Soc Interface (in print) doi:10.1098/rsif.2009.0063

Raffel M, Gharib M, Ronneberger O, Kompenhans J (1995) Feasibility study of three-dimensional PIV by correlating images of particles within parallel light sheet planes. Exp Fluids 19(2):69–77

Raffel M, Westerweel J, Willert C, Gharib M, Kompenhans J (1996) Analytical and experimental investigations of dual-plane particle image velocimetry. Opt Eng 35:2067

Sengupta P, Khandheria B, Korinek J, Jahangir A, Yoshifuku S, Milosevic I, Belohlavek M (2007) Left ventricular isovolumic flow sequence during sinus and paced rhythms new insights from use of high-resolution doppler and ultrasonic digital particle imaging velocimetry. J Am Coll Cardiol 49(8):899–908

Wang L, Shandas R (2007) 12B-4 Real-time multi-component hemodynamic measurement in vascular aneurysms using echo particle image velocimetry: comparison of in vitro and computational results, IEEE ultrasonics symposium, 2007, pp 1097–1100

Westerweel J (1997) Fundamentals of digital particle image velocimetry. Meas Sci Technol 8(12):1379–1392

Westerweel J (2008) On velocity gradients in PIV interrogation. Exp Fluids 44(2):831–842

Westerweel J, Scarano F (2005) Universal outlier detection for PIV data. Exp Fluids 39(6):1096–1100

Westerweel J, Draad A, Hoeven J, Oord J (1996) Measurement of fully developed turbulent pipe flow with digital particle image velocimetry. Exp Fluids 20(3):165–177

Zheng H, Liu L, Williams L, Hertzberg J, Lanning C, Shandas R (2006) Real time multicomponent echo particle image velocimetry technique for opaque flow imaging. Appl Phys Lett 88:261–915

Acknowledgments

This work was partially funded by the TU Delft in the IDEA league framework.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

For a harmonic driving force, the radial profile of the axial velocity in a circular pipe with radius R is described by (McDonald 1974):

with A * the complex amplitude of the driving force, μ the dynamic viscosity and ω the angular frequency, ω = 2π/T. α represents the Womersley number, α = R(ω/ν)1/2. J 0 is a Bessel function of the first kind, zeroth order.

For a non-zero mean velocity, the Poiseuille solution can be added to Womersley’s solution:

with B the time-averaged centerline velocity. The latter is determined from the time-averaged velocity profile. The parameter A * is fitted to match a single instantaneous velocity profile; subsequent velocity profiles at later times are then calculated using this value.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Poelma, C., Mari, J.M., Foin, N. et al. 3D Flow reconstruction using ultrasound PIV. Exp Fluids 50, 777–785 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00348-009-0781-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00348-009-0781-8