Abstract

The vortex organization of cylinder wakes is experimentally studied by time-resolved tomographic Particle Image Velocimetry at Reynolds numbers ranging from 180 to 5,540. Time resolved measurements are performed at Re = 180, 360 and 540, whereas the transitional (Re = 1,080) and turbulent regimes (Re = 5,540) are investigated by snapshots separated in phase by more than π/4. The vortex structure evolution is visualized by the 3D vorticity field, revealing a regular shedding at the lowest Reynolds, whereas at Re > 500 the Bénard-Kármán vortex street exhibits counter-rotating stream-wise vortex pairs (characteristic of Mode B) dominating the 3D motion. The regime at Re = 360 produces a transitional pattern where the counter-rotating vortex pairs (Mode B), coexist with profoundly distorted shedding of oblique elements forming a chain of rhombus-like vortex cells. In the turbulent flow regime (Re = 5,540) a large increase in the range of flow scales is directly observed with the appearance of Kelvin-Helmholtz type vortices in the separated shear layer consistently with what is abundantly reported in literature. The statistical description of the secondary structures is inferred from a 3D autocorrelation analysis yielding two span-wise wavelengths for the counter-rotating pairs, an inner length given by (twice) the distance between counter-rotating elements and an outer one given by the distance between pairs. The uncertainty analysis of the present tomographic PIV experiments reveals that this approach is suited for the investigation of vortex wakes with a typical error of 2 and 10% on the velocity and vorticity vectors, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The flow around circular cylinders has been the subject of a multitude of scientific studies. Although simple from a geometrical point of view, the wake of the cylinder exhibits a wide variety of flow phenomena having direct relevance for many practical fluid-structure interaction problems. Due to this richness, it has become the archetype for the study of unsteady flows (Berger and Wille 1972).

The two-dimensional behavior of the cylinder wake—the classical Bénard-von Kármán vortex street first observed by Bénard (1908)—is now well understood. The appearance of three-dimensional vortex structures at relatively low Reynolds numbers (and their behavior at increasing Reynolds number) has seen an increase in attention in more recent years (Williamson 1996). Examples of numerical studies can be found, e.g., in works by Braza et al. (1986, 2001) and Thompson et al. (1994). Experimental efforts to obtain an accurate characterization of the three-dimensional vortex pattern are reported by Williamson (1988), Wu and Sheridan (1994) and Brede et al. (1996) among many others. An early 3D iso-surface rendering of stream-wise vorticity based on spatio-temporal reconstruction was obtained by Lin et al. (1995a, b), whereas Floquet stability analysis theoretically consolidated the definition of two modes in the 3D wake of cylinders (Barkley and Henderson 1996). The earliest 3D transition, denoted as mode A, is associated with the inception of vortex loops in the main rollers around Re = 190, which distorts the primary rollers with a span-wise wavelength λ z between 3 and 4 diameters. Increasing the Reynolds number to about 250, the wake pattern becomes dominated by stream-wise vortex pairs spaced by a distance of approximately one diameter (also referred to as Mode B). These two modes have been identified as the dominant features for the three-dimensional organization of coherent structures in the 3D regimes of cylinder wakes. In particular, mode B is characterized by a shorter span-wise wavelength (λ z /d ~ 1 between counter-rotating stream-wise rollers). Moreover, Mode B is reported to persist also higher Reynolds, typically up to about Re = 1,000 (Williamson 1996).

The PIV experiments conducted in the range Re = 200–500 by Brede et al. (1996) enabled a quantification of the vorticity content of secondary structures returning a detailed analysis of these secondary vortices. At Reynolds numbers in the order of 104, in the fully turbulent regime, stream-wise vortices, and their interaction with the Kármán rollers were visualized by Muchmorea and Ahmed (1992) who reported mushroom-shaped structures interconnecting the span-wise rollers. A more recent PIV survey along orthogonal planes performed in the range Re = 2,000–10,000 (Huang et al. 2006) reported details of the vorticity in the secondary rollers and proposed a vortex organization topology consistent with the Mode B structure.

Since the early computations of Fromm and Harlow (1963), today’s direct numerical simulation (DNS) approach yields great contributions in the understanding of the vortex organization and in the accurate definition of the critical values of the Reynolds number at which transition occurs (Thompson et al. 1994). However, the range of new phenomena observed by experiments such as vortex dislocations, cellular shedding (among which a new one is found in the current study), and oblique shedding, are found back in only some numerical studies (Braza et al. 2001; Poncet 2004), at low Reynolds numbers. On the other hand, the laboratory experiences performed at moderate or high Reynolds (Perrin et al. 2007) have made use of planar PIV as the most up-to-date diagnostic technique. Consequently, the complex three-dimensional features must be inferred from planar sections of the flow field, which motivates to study the wake in the transitional and turbulent regime by a full three-dimensional technique. An effort using tomographic PIV (Elsinga et al. 2006) has been reported by Scarano et al. (2006). However, such experiments conducted in air flow and in the turbulent regime did not allow describing the time evolution of the vortex pattern.

The present work utilizes this recently developed three-dimensional diagnostic technique to measure the instantaneous velocity and vorticity vector fields. This allows a three-dimensional inspection of the vortex organization and time-evolution of the cylinder wakes. The focus of the investigation is the shedding process and early development of the wake, which is obtained by a measurement domain spanning eight diameters along the stream- and span-wise direction and over a width of two diameters. Temporally resolved experiments are made possible by utilizing a water tunnel, thus allowing to describe the flow regime up to Re = 540 with approximately 10 samples/cycle.

2 Experimental apparatus

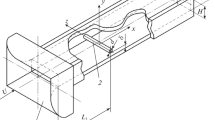

The experiments are performed in the water channel of the Laboratory for Aero and Hydrodynamics of Delft University of Technology. The facility features a 60 × 60 cm2 cross-section channel 10 m long with a flow speed varying in the range between 2 cm/s and 1 m/s; a series of meshes in the settling chamber and a high-ratio contraction result in a free-stream turbulence level below 0.5%. A cylinder with diameter d = 12 mm and 60 cm length (aspect ratio of 1:50) is installed vertically in the mid section of the channel 50 cm downstream of the contraction (Fig. 1). Thin end plates are attached at 1 cm from the ends of the cylinder. The upper one serves to reduce the effect of flow distortion on the free surface due to the interaction with the partly submerged optical interface for laser light access. On the bottom wall the end-plate reduces the interference of the cylinder with the thick boundary layer developing at the channel wall. Moreover, these devices are opened along a slit, downstream of the cylinder to allow laser light to pass through. As a result, they have the additional function of optical knife-edge filters. Finally, a plane mirror is installed on the bottom wall that reflects the laser light back toward the measurement domain. Measurements are performed around and in the near wake of the cylinder varying the free-stream velocity covering the following range of Reynolds number Re = {180, 360, 540, 1,080, 5,540} based on the cylinder diameter.

The flow is seeded with Vestosynt (Degussa-Hüls, Frankfurt, Germany) particles of 56 μm diameter at a concentration of approximately 0.5 particles mm−3. In water at a temperature of 15°C, the particle density of 1.016 g cm−3 yields a settling velocity smaller than 50 μm s−1. The illumination over a volume of 100 × 100 × 20 mm3 (L × H × W, corresponding to 8.3 × 8.3 × 1.7 d3) is provided by a Quantel CFR 200 Nd:YAG laser with an output of 200 mJ/pulse and a repetition rate up to 30 Hz. The thick laser beam is obtained by a beam expander and by a cylindrical lens, returning an illuminated cross-section of 24 mm width. The aforementioned knife-edge filters reduce this region to 20 mm at the measurement location yielding a quasi top-hat light intensity distribution, which favors the accuracy of the tomographic reconstruction. Four LaVision Imager Pro X cameras (2,048 × 2,048 pixels, 14 bits) are placed subtending a solid angle of approximately 40° × 40°. Nikon objectives with a 60 mm focal length are mounted on tilt-axis lens-camera adapters to comply with the Scheimpflug condition with respect to the median plane of the illuminated volume (Prasad and Jensen 1995). Although a numerical aperture f # of 11.2 would be sufficient for a focal depth of 20 mm, the presence of aberrations due to the air/water interface made it necessary to increase the numerical aperture to 32 to limit the aberration of particle images. As a consequence, the imaging process is governed by diffraction, yielding particle images of approximately 5 pixels. The chosen magnification yields a typical digital resolution of 20 pixels/mm. The illumination and recording devices are synchronized and controlled by a LaVision programmable timing unit (PTU v9) controlled by DaVis 7.3 software. Each measurement consists of 75 quadruplets of image pairs at a recording frequency of 7 Hz, which is only sufficient to capture the temporal behavior of the flow up to Re = 540 (approximately ten samples per shedding cycle). The number of quadruplets is limited by the RAM memory available on the cameras. Approximately 70,000 to 100,000 particle images are recorded within each frame, corresponding to a particle imaging density up to 0.025 particles per pixel (ppp). The corresponding source density (Adrian and Yao 1985) is N s = 0.4.

2.1 Tomographic PIV

The tomographic reconstruction technique is extensively discussed in the study of Elsinga et al. (2006) and only the essential features relevant to the present experiment are reported herein. The tracer particles, immersed in the flow and illuminated by a pulsed light source within a three-dimensional region of space, are recorded as particle images in focus from several viewing directions using CCD cameras (Fig. 2). The Scheimpflug condition between the image plane, lens plane and the median-object-plane needs to be fulfilled in order to record focused particle images. This is achieved in practice by means of camera-lens tilt mechanisms with free orientation of the tilt rotation axis and selecting an appropriate focal depth by the lens aperture.

The reconstruction of the 3D object from the digital images requires an accurate 3D mapping function between the image planes and the physical space. This is achieved by a calibration procedure similar to that of stereoscopic PIV, except that a 3D domain instead of a single plane is covered by such mapping. For stereo-PIV, the alignment of the calibration target and measurement volume (in practice the laser light sheet) is known to be critical: a small misalignment can lead to systematic registration errors (van Doorne and Westerweel 2007). For tomographic PIV the registration error is not an issue, as the entire volume is calibrated, making the calibration procedure comparatively less dependent upon accurate laser alignment. However, as discussed by Elsinga et al. (2006) and more recently by Wieneke (2008), the requirement for the relative position accuracy between cameras for the tomographic technique must not exceed a small fraction of the particle image diameter, which is significantly more stringent than that for planar stereo-PIV, which is able to tolerate misalignments of a small fraction of the interrogation window. This can be achieved by an a posteriori correction of the calibration mapping function based on a 3D disparity vector field developed by Wieneke (2008), similar to the light sheet misalignment technique used in stereo PIV proposed by Willert (1997).

The calibration is therefore performed in two steps: first, the 3D mapping function is experimentally determined recording the images of a calibration plate sliding at five positions spanning the whole measurement volume depth of 20 mm. Typical calibration errors at this point are of the order of 1 pixel. Subsequently, the calibration map is refined by the self-calibration technique to minimize the disparity fields. This process results in a decrease of the calibration error to values smaller than 0.1 pixels, which is acceptable for an accurate tomographic reconstruction.

2.1.1 Tomographic reconstruction of particle images

A schematic description of the steps needed to obtain the 3D velocity field from a quadruplet of image pairs is given in Fig. 3. The 3D distribution of light scattered by the particle tracers is reconstructed in the form of a discrete 3D array of voxels representing the light intensity in physical space also referred as the object, E(X, Y, Z) from its projections on the CCD arrays. This reconstruction is achieved by the so-called multiplicative algebraic reconstruction technique (MART, Herman and Lent 1976), which is implemented iteratively. The accuracy of the reconstruction process strongly depends upon several factors as discussed by Elsinga et al. (2006), the most important being the number of viewing cameras and the image source density. Other parameters affecting the accuracy of reconstruction are the viewing angle, the width and intensity distribution of the illuminated domain and the amount of background and spurious light. According to the numerical evaluation of Elsinga et al. (2006), systems with two cameras are only adequate for very low seeding density (below 0.01 ppp), whereas the most commonly used configuration with four cameras is able to deal with a particle image density of 0.05 ppp (i.e. 50,000 particles/Mpixel) with an acceptable reconstruction accuracy. In the present investigation, a particle image density of 0.025 is obtained with individual particle images of 5 pixels diameter.

The reconstruction of the light intensity field by the MART algorithm is implemented in the DaVis 7.3 software from Lavision. The measurement volume is discretized with an array of 1,410 × 1,590 × 400 voxels (L × H × W, 80 × 90 × 20 mm3) obtained applying a pixel to voxel ratio of 0.8. This ratio reduces the requirement on computer memory to half compared with that needed for a pixel to voxel ratio of one. This does not affect significantly the accuracy of the reconstruction because the particle images are sufficiently well resolved in space. The MART algorithm is iterated six times after which the final result does not change with further iterations. The overall procedure is computationally expensive: the procedure utilizes 4 GB RAM memory and requires 30 min for the reconstruction of one object pair on a PC with two quad-core Intel Xeon processors at 2.66 GHz. Moreover, the memory required to store a single object at 16 bits is approximately 800 MB from the initial 40 MB of the four raw image pairs. However, when only the non-zero voxels are considered, the needed storage reduces to 120 MB.

It is important to verify a posteriori the accuracy of the reconstruction process by inspection of the light intensity distribution along the depth of the reconstructed volume. Figure 4 left shows a top-view (x–z plane) of the light intensity map averaged along the y-coordinate direction (parallel to the cylinder axis). Only for illustration purpose a region significantly larger than the illuminated one is reconstructed in this case. The edges of the illuminated region are clearly detected that allow determining the actual thickness and intensity profile of the laser light.

The reconstructed light intensity also allows visualizing and locating the surface of the cylinder, highlighted by the dashed black circle. When the intensity is also averaged along the x-coordinate direction (except for the region of the cylinder and at the border) the light intensity profile clearly shows the difference in the intensity of reconstructed light within the illuminated region and the one outside that is ascribed to noise. A signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of two or more is inferred from this analysis (Fig. 4 right). It can also be observed that the presence of the cylinder in the field of view introduces some artifacts both in the illuminated region and outside. In the region above the cylinder (x = 300, z = 400) a higher SNR is to be expected because the shorter width decreases the probability that ghost particles are formed (Elsinga et al. 2006).

2.1.2 Particles displacement estimation

The evaluation of the reconstructed particle pattern displacement is performed by means of an iterative 3D spatial cross-correlation analysis. The normalized cross-correlation function R(ΔX, ΔY, ΔZ) of a pair of exposures obtained at two time instances separated by the pulse interval Δt, reads in this case as:

where the triplet (i, j, k) is the indexing of the discretized spatial coordinates and (l, m, n) refers to the discrete spatial shifts. The analysis is performed with an iterative technique based on the window deformation technique (WIDIM, Scarano and Riethmuller 2000) extended to three dimensional intensity fields [volume deformation iterative multigrid (VODIM)]. The interrogation volumes are deformed relative to each other according to a local Taylor expansion to the first order of the measured velocity field, which is obtained in a previous iteration (Scarano 2002). This procedure ensures that no loss of particle-pairs occurs due to the particle pattern motion except for the unresolved flow scales and at the borders of the analyzed domain. The intensity field of the deformed volume at the k + 1th iteration is obtained from the original intensity and the predictor velocity field according to the expression

where \( \vec{V}_{d}^{k} = \left( {u_{d}^{k} ,v_{d}^{k} ,w_{d}^{k} } \right) \) represents the particle pattern deformation field obtained at the kth interrogation obtained by tri-linear interpolation of the displacement field at the previous iteration. Between subsequent iterations low-pass filtering by 2nd order 3D least squares regression is applied to the velocity field for process stabilization (Schrijer and Scarano 2008).

The reconstructed volumes are processed using 3D cross-correlation with the VODIM technique with an interrogation box size decreasing from 127 × 127 × 39 voxels to a final box size of 393 voxels and 75% overlap between adjacent interrogation boxes, yielding a velocity field measured over a grid of 128 × 146 × 36 points. For the given particle’s concentration and final interrogation box size, seven particles are present on average in the interrogation box. After each interrogation the resulting data is validated by the universal median test (Westerweel and Scarano 2005), with an outlier detection rate of approximately 3%. The cross-correlation is performed by means of three-dimensional FFT technique in the initial steps. At later stages it is computationally more efficient to evaluate the cross-correlation 3D map by direct multiplication: already after one or two steps, the iterative deformation technique makes it unnecessary to evaluate the complete correlation map. The latter is therefore only evaluated over a small neighborhood of the origin (typically 5 × 5×5 voxels shift). Moreover, the particle density in the 3D object is lower (typically by one order of magnitude) than that in the original images. Consequently, only 10–20% of the voxels is non-zero, which justifies the evaluation of the correlation map as a sum of the individual non-zero voxels. As an additional advantage, the voxel product maps only require to be computed once, irrespective of the interrogation box overlap, which makes the method significantly more efficient when window overlap of 50 or 75% are adopted, obtaining a computational efficiency increase by a factor of 8–64, respectively. The correlation map for each window is then obtained by summing up the contribution of the individual voxels product maps. In conclusion, this approach is particularly efficient for the tomographic PIV data, which is rather sparse 3D and yields an overall computational acceleration of about 50 times for the present case. The volume interrogation software VODIM runs in parallel on 16 processors of a UNIX cluster, currently requiring approximately 1 h for the evaluation of a single velocity snapshot at the given processing parameters.

2.2 Uncertainty analysis

The measurement precision of three-dimensional time-resolved measurements can be performed by a posteriori techniques based on physical criteria. Since the measurement error between subsequent recordings is uncorrelated, the shot-to-shot noise can be evaluated by comparing the velocity time history and a filtered version of it provided that the filter kernel length is smaller than the time scales present in the flow. This analysis is presented in Fig. 5 where the raw displacement at a given location is plotted against the filtered version of the velocity field by a second order polynomial least squares fit over a kernel of 54 points (space-time regression). This technique returns a visible reduction of the noisy fluctuations yet with no appreciable low-pass filtering effect due to the relatively high temporal and spatial resolution at Re = 180. The typical scatter of the raw measurements can be interpreted as representative of the measurement uncertainty. The standard deviation of the velocity fluctuations evaluated on the entire data ensemble returns an error of 0.1 voxels for the components u and v, and 0.15 voxels for the w component. The relative error on the velocity is approximately 1% considering that the particle displacement in the free-stream is 10 voxels.

The mass conservation principle can be used to ascertain the consistency of the measured velocity field as also proposed by Zhang et al. (1997). Although the flow divergence is not commonly a property of interest when dealing with incompressible vortex-dominated flows, its simple formulation makes it a suitable quantity to estimate the measurement errors on the spatial derivatives of the flow. For incompressible flows the velocity divergence must be zero everywhere: \( \nabla \cdot \vec{V} = \partial u/\partial x + \partial v/\partial y + \partial w/\partial z = 0. \)

The numerical evaluation of the divergence from experimental data, however, may be different from zero due to errors introduced by numerical truncation due to the spatial discretization. Nevertheless, as explained in Sect. 2.1.2, the large overlap factor between neighboring interrogation boxes ensures that truncation errors are negligible with respect to the effect of the finite size of the interrogation. The evaluation of the standard deviation of \( \nabla \cdot \vec{V} \) over the entire measurement domain and during the whole observation time is denoted by the symbol \( \left\langle {\left| {\nabla \cdot \left. {\vec{V}} \right|} \right.} \right\rangle \) and yields a statistical estimate of the measurement precision for the components of the velocity gradient tensor. The statistical distribution of \( \left\langle {\left| {\nabla \cdot \left. {\vec{V}} \right|} \right.} \right\rangle \) estimated by central finite differences is shown in Fig. 6 for Re = 180 and Re = 1,080 representative of the fully laminar and transitional regimes, respectively. The shaded area corresponds to the raw data, whereas the solid line represents the filtered data. The error distribution is symmetrical around zero with Gaussian width of 0.01 and 0.005 voxels/voxel for the raw and filtered data, respectively. At Reynolds higher than 180 the temporal filtering is not possible due to the low sampling rate and only a 3D spatial filtering is applied, which partly explains the smaller reduction in the measurement error with respect to the raw data. Moreover at higher Reynolds number the overall error is expected to slightly increase due to the occurrence of not fully resolved flow structures. At Re = 1,080, the term \( \left\langle {\left| {\nabla \cdot \left. {\vec{V}} \right|} \right.} \right\rangle \) is approximately 0.04 and 0.025 voxels/voxel for the raw and filtered data, respectively. These values can be considered as an upper bound for the error associated with the measurement of components of the velocity gradient tensor. This is because the measurement of the trace of the velocity gradient tensor (i.e. the velocity divergence) is usually less accurate than the non-diagonal terms. When the error is normalized by the typical values measured for the vorticity (0.3 voxels/voxel at Re = 1,080), a relative error of 5% in the laminar regime (Re = 180) and 8% in the transitional/turbulent regime are obtained, respectively.

3 Results and discussion

Animations illustrating the results are available as supplemental material. See www.lr.tudelft.nl/aerodynamics

3.1 Time-resolved shedding cycle in the laminar regime

At Re = 180 each shedding cycle is sampled 35 times at the given recording rate. In this case, the Bénard-Kármán counter-rotating vortices dominate the unsteady behavior, shedding alternatively from the upper and lower side of the cylinder centerline. In Fig. 7 the instantaneous flow velocity and vorticity field is visualized; the primary rollers can clearly be observed as the iso-surfaces of ω y (the red and blue structures in Fig. 7 right). The vorticity components have been normalized using the free-stream velocity and the cylinder diameter (ω* = ωd/V ∞ ).

The Strouhal number (St = fd/V ∞ , with f the shedding frequency) estimated for this experiment is 0.18, which is in agreement with the results from Williamson (1988). The shedding mechanism has been clearly described in numerous previous studies (Gerrard 1966; Perry et al. 1982, among others). The forming vortex on one side draws the shear layer of opposite sign toward the wake centerline. At some distance from the cylinder the shear layer from the opposite sign cuts off the supply of vorticity to the growing vortex, which then detaches from the shear layer. Around this Reynolds number, the first 3D instabilities can be expected to appear in the predominantly two-dimensional wake: long span-wise wave modes are observed. The so-called “vortex loops” are usually referred to as Mode A instabilities and later referred to as 3D wake distortion by Williamson (1996). The transitions from a strictly 2D wake to this mode causes a discontinuous decrease in the St-Re diagram in the range Re = 180–210. The behavior is hysteretic, with mode A persisting even below Re = 180 when the flow regime is approached from higher free-stream velocities. The current measurements, however, show only marginal three-dimensional activity of Mode A type with a pattern resembling the results from the 3D Floquet stability analysis of Barkley and Henderson (1996), who found small 3D structures distorting the Kármán rollers superimposed to the 2D wake dominated by the parallel shedding regime. As revealed in Fig. 7 right, vortex structures containing vorticity in the x–z plane are very weak compared to the main rollers. The normalized vorticity level of the main rollers is ω y * ≡ ω y /(V ∞ /d) = 1.6, and that of the secondary structures is ω x–z * = 0.8. Occasionally, quasi-stream-wise counter-rotating vortex pairs are also observed in a pattern resembling Mode B, which is characteristic of higher Reynolds number flows as described in the next section.

3.2 Three-dimensional transition

At Re = 360 the cylinder wake has fully entered the 3D regime. In this Reynolds number range, most experiments (Williamson 1995) and numerical simulations (Thompson et al. 1994) show a fully developed 3D flow with counter-rotating vortex pairs appearing in the vortex formation region, perpendicular to the primary rollers (Mode B). The counter-rotating vortex pairs are stretched by the separation of the main rollers and accelerated after the shedding process. The current measurements yield a more complex behavior because of the coexistence of two clearly different patterns. The structure of Mode B is observed in the vorticity visualization of Fig. 8, where finger-shaped longitudinal vortices (colored in yellow and cyan to code the rotation direction) are present at the inception of shedding and develop longitudinally in between the span-wise rollers. For clarity the vorticity on the upper side of the cylinder is not drawn (only visible on the top part of the vector slice); otherwise it would mask the underlying internal structure of the secondary vortices. Figure 8 right shows the vorticity iso-surfaces color-coded by the vorticity stretching-tilting term \( \left( {\vec{\omega }\left( {\vec{\nabla }\vec{V}} \right)} \right). \) The maximum activity is measured at the upstream fingertips of the longitudinal rollers indicating a re-orientation of span-wise vorticity due to Mode B instability and the subsequent amplification under the action of stretching. A similar result was predicted by numerical simulations (Poncet 2004) where a peak in the main growth mode is located approximately 1.5 diameters downstream of the cylinder axis. The vortex pairs have one extremity upstream of the main roller and are oriented in the x–z plane between the Kármán rollers. These results confirm the Mode B schematic inferred from planar PIV experiments conducted by Brede et al. (1996) at Re = 280, where also a 3D field reconstruction from planar measurements was obtained applying Taylor’s hypothesis. The span-wise arrangement of the secondary vortices in the current result also exhibits the expected periodicity at λ z /d = 1. However, as it will be discussed later, the arrangement of the counter-rotating vortices does not appear completely periodic: the distance between vortices composing a single pair is often smaller than half the distance between rollers of the same rotation. This may suggest the definition of two different wavelengths: λ z1 as the intrinsic wavelength of the vortex pair and λ z . corresponding to the distance between adjacent pairs. It is observed in the present experiments that λ z is frequently larger than twice λ z1 . Finally, the maximum value of the span-wise vorticity component is attained during vortex formation: ω y * = 2.4. Whereas the vorticity in the counter-rotating vortex pairs exhibits the highest value with the stream-wise-normal component ω x–z * = 3.0. The description by iso-surfaces in Fig. 8 left is given with a choice of ω* = 1.2.

Detail of counter-rotating vortex pairs at Re = 360. Left vorticity iso-surfaces (blue ω y * = −1.2, yellow ω x–z = +1.2, magenta ω x–z = − 1.2). Velocity vectors slice in background (ω y color-coding). Right vorticity iso-contours color-coded with vorticity stretching-tilting rate \( \vec{\omega } \cdot \left( {\vec{\nabla }\vec{V}} \right). \) Note upper shear layer not displayed for clarity

3.3 Rhombus vortex-cells

The present experiments also revealed a clearly different vortex organization at the same Reynolds number Re = 360. This pattern is illustrated in Fig. 9 by four subsequent snapshots separated by one-fifth of the shedding period. The flow structures of interest are labeled (1, 2 and 3 following their appearance in time) to facilitate the tracking of features. The near-wake structure exhibits counter-rotating vortex pairs along the left half of the measurement domain. Approximately in the middle of the scene, the scenario is significantly different from mode B because clear oblique structures are exhibited, which appear to organize along a thread-like sequence. During this transient event vortices appear to form rhombus-like cells. The phenomenon is only apparently similar to the honeycomb pattern observed by Cimbala et al. (1988) and later referred by Williamson (1996) to as a 3D wake distortion. A detail of such a rhombus-like cell is shown in Fig. 10. Because of the exhibited features, this phenomenon will be referred to as rhombus vortex cell in the remainder of the present study.

This shedding mode is not directly comparable with those reported in literature and some details are given here. However, due to the complexity of such dynamical 3D pattern, a visualization of the time evolution of a rhombus vortex cell is better clarified with video animations (see Sect. 3 footnote). During this process the span-wise coherence of the vortex formation from the separated shear layer and the shedding phenomenon are dramatically broken by vorticity filaments being torn apart of the vorticity sheet on the cylinder surface and shed obliquely during the roll-up process. Each vortex filament detaches from the deformed vorticity sheet and is stretched along its axis further increasing its core vorticity. The overall pattern may have some commonalities with the “vortex dislocation” mechanism first investigated by Gaster (1969) for flows around cones and thoroughly investigated in later studies by Persillon et al. (1997) and Braza et al. (2001). According to the vortex dislocation mechanism, a strongly localized, tilting process occurs that produces a pair of quasi-stream-wise vortices. Clear observations of vortex dislocation are presented in this study; however, they appear more clearly at a higher Reynolds numbers (Re = 540 and Re = 1,080). At the occurrence of dislocation the loss-of-coherence of the main roller is well localized along the span and typically extending for about one diameter. Moreover, when a vortex pair is formed, the primary roller is distorted by a symmetrical tilting mechanism leading to the stream-wise pair of counter-rotating vortices. Instead for the formation of a rhombus vortex cell such tilting is anti-symmetric and each vortex of the pair is taken from opposite sides of the cylinder. As a result, the vortices do not tend to align along the stream-wise direction and remain oblique at approximately 45°.

The phenomenon observed here may be explained as a self-sustained mechanism by Biot-Savart induction between tilted vortices (tilt angle 45° in the x–y and x–z planes) from the opposite sides of the wake and to the authors’ knowledge such self-sustained shedding pattern has not been reported in previous studies yet. Although in first analysis the combination of multiple self-induced oblique vortices leading to a cellular shedding pattern could be compared with the much discussed honeycomb-like pattern visualized by Cimbala et al. (1988), the latter honeycomb structure is a characteristic of the far wake and it was explained as a specific interaction between oblique shedding and 2D large-scale waves growing in the far wake. In contrast, the present situation occurs in the near wake during vortex formation (x/d < 2), and appears almost as localized as vortex dislocation. Furthermore, the coherence of the span-wise shedding is affected over 2 to 3 downstream diameters, and the parallel shedding is replaced by a self-organized oblique alternate shedding from both sides of the wake. The resulting vortex pattern yields a chain rhombus vortex cells intertwined and following each other stream-wise like a thread. Within a rhombus vortex cell the vortices from opposite sides of the cell induce flow in the same direction. The vorticity and vorticity stretching in rhombus cell regime is |ω|* = 4.0, higher than that encountered in the vortex pairs of Mode B with |ω|* = 2.4. This may be explained by the fact that the stretching process for the rhombus cell vortices lasts longer. The shedding frequency corresponding to this mode is difficult to evaluate because the phenomenon, although occurring systematically (rhombus vortex cells have been repeatedly tracked for several shedding periods), is not sufficiently regular and it has an intermittent character, which deserves further investigation. It is, however, expected that the shedding process will have a higher frequency since the formation time for the oblique vortices is shorter than that of the Kármán vortices.

Increasing the Reynolds number to 540 the 3D wake pattern becomes completely dominated by stream-wise vortices (Mode B) in the near wake and no occurrence is observed of rhombus vortex cells. Interestingly, significant span-wise variations of the vorticity in the shear layer prior to the shedding of the main roller are correlated with the location of stream-wise vortices forming on the main roller. This is particularly evident in Fig. 11 right where the iso-surface corresponding to the core of the shear layer (in red) has a span-wise quasi-periodicity (already visible in Fig. 11 center), which degenerates further as the shedding process progresses. The effect of these secondary structures inter-connecting the Kármán rollers appears to stabilize the phase of the roll-up process, returning a more parallel shedding as compared to the lower Reynolds number case. A span-wise waviness of the Kármán rollers is visible at starting or ending locations of fingertip vortices. Such pattern has been consistently reproduced in the simulations at Re = 1,000 performed by Poncet et al. (2008). Moreover, the arrangement of secondary vortices as shown in Fig. 12 exhibits vortex pairs spaced by a larger distance than that between individual rollers. At this Reynolds, λ z1 is less than half a diameter (2λ z1 /d ~ 0.6) as shown in Fig. 12, whereas the typical distance between pairs λ z is larger than the twice the inter-axial distance (λ z /d = 1.2). This may suggest that the configuration with two counter-rotating rollers can also occur somehow isolated from other vortex pairs, such that to return a quasi-periodic system of stream-wise vortex pairs. These qualitative observations are later confirmed by a 3D vorticity pattern cross-correlation analysis. Finally, the peak vorticity encountered at this Reynolds does not differ significantly from the previous case, with the maximum span-wise vorticity component ω y * = 3.0 and ω x–z * = 4.0.

Mode B at Re = 540. Left vorticity iso-surfaces (color-coding same as in Fig. 8). Right vorticity iso-contours color-coded with the vorticity stretching-tilting rate \( \vec{\omega } \cdot \left( {\vec{\nabla }\vec{V}} \right) \) (small values in blue, high values in red)

3.4 Shear-layer transitional regime

At Re = 1,080, the separated shear layer further elongates, with the roll-up process shifted downstream, at approximately two diameters from the cylinder axis. In Fig. 13 a visualization at three time instants temporally separated by one-fifth of the shedding period is given. Although the counter-rotating vortex pairs are clearly present in the 3D wake organization, the correlation between the inception point of such vortices and the core region of the separated shear layer is less clear than for the case at lower Reynolds. Moreover, the span-wise variations in the shear layer appear to be less dependent of the phase in the shedding cycle. The counter-rotating vortex pairs dominate the region between main rollers; however, these structures now exhibit a smaller cross-section, typically d/3, and are shaped as filaments. Consequently, this pattern resembling Mode B exhibits a higher spatial frequency with respect to the lower Reynolds number cases. The secondary rollers are also observed to undergo mutual interaction, characterized by the precession of counter-rotating vortices and in some cases pairing of co-rotating vortices is observed. These interactions often lead to further three-dimensional distortion of the vortex pattern in the wake. Although the final outcome of this process becomes increasingly complex, the wake vortex system self organizes after the shedding with the Kármán roller embedded in a net of vortex filaments trapped and wrapped around the main structure. This yields a disordered patch of fluctuating vorticity, nevertheless with considerable span-wise coherence. The maximum values of the vorticity components are found at ω y * = 3.5 and ω x–z * = 5.0 for this case.

3.5 The turbulent regime

Experiments conducted at Re = 5,500 only allow the analysis of individual snapshots because the time separation between recordings is 1.1 times the shedding period. As a result, subsequent recordings are shifted in phase, approximately 10% in phase with respect to the previous shedding. This circumstance still allows inferring to a certain extent the spatial organization of the wake and proposes a qualitative description of the wake evolution considering that the shedding process keeps globally self correlated for several shedding periods.

A cross-sectional view allows to visualize the shear layer transition pattern resembling that reported for mixing layers where the Kelvin-Helmholtz instability induces the formation of co-rotating vortices rolling-up within the shear layer. This process produces fluctuations that scale with the thickness of the separated shear layer and will superimpose to the scales of the Karman vortex shedding. In the case of the cylinder wake, the development of these vortices is limited by the short formation region. Therefore only two to three mixing layer vortices are observed in the upper shear layer as nuclei of vorticity (Fig. 14). This pattern agrees qualitatively with those visualized by the PIV experiments of Lin et al. (1995a). It should be retained in mind that the planar visualization suggests that the flow features (vortices in the present case) observed in the measurement plane extend along the transverse direction. This aspect is not often verified because of the technical difficulty to capture the three-dimensional structure of the Kelvin-Helmholtz vortices belonging to a curved shear layer within a fixed plane for PIV experiments. Moreover, at such Reynolds number visualization techniques based, e.g., on dye injection are unsuited to infer the 3D flow pattern due to the rapid loss of contrast associated with the powerful turbulent mixing. This partly explains why numerical simulations of the flow have been, in this regime, most helpful for flow pattern visualization (Braza et al. 1986). The span-wise waviness of the shear layer at the end of the formation region is illustrated in Fig. 15, where it is shown that most of these structures lose correlation within approximately one diameter. This is larger than their inner length scale corresponding approximately to the separated shear layer thickness. In most cases they appear oriented at a small oblique angle between 10 and 20°.

In this experiment, the transition region appears at a normalized distance from the separation line x T/d = 1. This transition line is undulated, which can be inferred from the intermittency of the peak vorticity in the shear layer. Even at this Reynolds number the most evident 3D coherent phenomenon in the wake is the existence of counter-rotating quasi-stream-wise vortex pairs. However, these do not appear to survive the first shedding period due to the strong rate of stretching and the inherent three-dimensional structure of the flow.

Remarkably, the global process of vortex formation and shedding recovers a more regular pattern in this regime. The counter-rotating vortices only appear in the roll-up phase and a rapid decay into rather isotropic turbulent structures is observed by vortex filaments trapped/wrapped around the Kármán rollers. This leads to a parallel street of vortices forming the wake. Each vortex core structure is formed by small-scale coherent vorticity fluctuations, which although disconnected from each other are not yet isotropic (because azimuthally elongated). Therefore, they exhibit some correlation at such stage of the wake development. It does not surprise how such organized motion embedded in a turbulent chaotic environment has been often taken as example or prototype for the debated definition of a coherent structure since the pioneering experiments reported by Roshko (1961).

4 Span-wise periodicity

Summarizing, over the investigated flow regimes the three-dimensional flow structure is dominated by the Mode B counter-rotating vortex pairs, which is consistent with results widely reported in literature. In contrast, two characteristic length scales, rather than a single one, may be identified for the counter-rotating vortices organization. The inner distance between counter-rotating vortice cores appears significantly smaller than half the distance between pairs. This statement is drawn, however, from the observation of a limited number of snapshots. A more complete statistical analysis of the probability density function for these distances is needed to formulate a more conclusive statement. On the basis of a 3D autocorrelation analysis (an example is shown in Fig. 16) of the component ω z it is concluded that such normalized distance λ z1 /d is significantly less than 1, with the details reported in Table 1. The value of unity widely reported in literature could be a consequence of the data averaging process applied to a phenomenon with intermittent nature. Conversely, the more conventional distance reported in literature λ z /d between vortex pairs, has been evaluated analyzing the 3D auto-correlation of only the positive part of the vorticity ω + z . The result is a normalized wavelength λ z /d from 30 to 80% larger than twice the inner distance. Finally, the analysis of the span-wise and complementary vorticity components ω y * and ω x–z * shows that they increase monotonically with Re with the latter dropping abruptly at the lowest Re where stream-wise little or no activity is observed in terms of secondary vortices.

5 Conclusions

The three-dimensional structure and time evolution of the vorticity pattern in cylinder wakes has been studied by experiments performed in a water tunnel with time-resolved tomographic PIV. The measurement domain includes the cylinder wake with a width of approximately two diameters and eight diameters along span and stream-wise directions. This allows measuring the flow in the separated shear layers and to obtain details of vortex formation and growth. The current experiments are still limited by the low recording rate, which only allows following the flow time evolution up to Re = 540 and the 3D measurements at Reynolds number up to 5,540 were performed without resolving the flow behavior in time. Time-resolved experiments for the latter case would require a hardware with a repetition rate of 30 Hz or higher, which may become possible with a conventional PIV system based on Nd:YAG lasers and CCD cameras. Beyond those flow regimes time resolution can only be achieved using high-repetition rate systems based on Nd:YLF and CMOS sensors, as recently realized by Schröder et al. (2008).

Although the requirement for raw data storage in time-resolved tomographic PIV is not very different from a planar PIV experiment (at most four times with respect to two-component measurements), the digital data storage for reconstructed tomograms is currently challenging computer systems with more than one order of magnitude increase. The bottleneck of the experimental procedure remains the processing time required for the reconstruction and processing of the tomograms (several hours per snapshot on parallel computing). This aspect should therefore receive attention in order to optimize the computational efficiency of 3D and 4D algorithms. Given the experimental results, it may be concluded that the tomographic PIV technique in combination with water facilities constitute a suitable approach for the time-resolved study of complex three-dimensional flows.

The measurements of the cylinder wake in the laminar regime at Re = 180 show that the relevant time and length scales in the flow can be completely resolved within the shedding process. Three-dimensional instabilities are well captured essentially under the form of counter-rotating vortex pairs (mode B) starting from Re = 360, where also a different shedding regime has been observed with respect to those reported in literature. This regime is characterized by a self-sustained chain of rhombus vortex cells, which shares some commonalities with vortex dislocation but is asymmetrical. The conditions under which this phenomenon can occur systematically in the wake will be the subject of further investigations. Using spatial cross-correlation, it was found that the stream-wise vortex pairs, characteristic of Mode B, appear to have an inner and an outer length scale. The experiments performed at higher Reynolds show that the shedding process re-establishes its overall regularity due to the presence of quasi-periodic stream-wise vortex pairs stabilizing the stream-wise position of the roll-up process. The Kármán rollers are locally distorted at fingers’ inception in agreement with the model of vortex-dislocation. In the transitional/turbulent regime, the flow pattern appears still strongly dominated by the counter-rotating secondary rollers along with the occurrence of a broader range of flow scales.

References

Adrian RJ, Yao CS (1985) Pulsed laser technique application to liquid and gaseous flows and scattering power of seed materials. Appl Opt 24:44

Barkley D, Henderson RD (1996) Three-dimensional Floquet stability analysis of the wake of a circular cylinder. J Fluid Mech 322:215–241

Bénard H (1908) Formation de centres de giration à l’arrière d’un obstacle en mouvement. C R Acad Sci Paris 147:839–842

Berger E, Wille R (1972) Periodic flow phenomena. Annu Rev Fluid Mech 4:313

Braza M, Chassing PH, Minh HHA (1986) Numerical study and physical analysis of the pressure and velocity fields in the near wake of a circular cylinder. J Fluid Mech 166:79–130

Braza M, Faghani D, Persillon H (2001) Successive stages and the role of natural vortex dislocations in three-dimensional wake transition. J Fluid Mech 439:1–41

Brede M, Eckelmann H, Rockwell D (1996) On secondary vortices in the cylinder wake. Phys Fluids 8:2117

Cimbala JM, Nagib HM, Roshko A (1988) Large structure in the far wakes of two-dimensional bluff bodies. J Fluid Mech 190:265

Elsinga GE, Wieneke B, Scarano F, van Oudheusden BW (2006) Tomographic particle image velocimetry. Exp Fluids 41:933–947

Fromm J, Harlow FH (1963) Numerical solution of the problem of vortex street development. Phys Fluids 6:975–982

Gaster M (1969) Vortex shedding from slender cones at low Reynolds numbers. J Fluid Mech 38565

Gerrard JH (1966) The mechanics of the formation region of vortices behind bluff bodies. J Fluid Mech 25:401–413

Herman GT, Lent A (1976) Iterative reconstruction algorithms. Compt Biol Med 6:273–294

Huang JF, Zhou Y, Zhou T (2006) Three-dimensional wake structure measurement using a modified PIV technique. Exp Fluids. doi:10.1007/s00348-006-0126-9

Lin J-C, Vorobieff P, Rockwell D (1995a) Three-dimensional patterns of streamwise vorticity in the turbulent near wake of a cylinder. J Fluids Struct 9:231–234

Lin J-C, Towfighi J, Rockwell D (1995b) Instantaneous structure of near wake of a cylinder: on the effect of Reynolds number. J Fluids Struct 9:409–418

Muchmorea B, Ahmed A (1992) On streamwise vortices in turbulent wakes of cylinders. Phys Fluids A 5:387

Perrin R, Cid E, Cazin S et al (2007) Phase-averaged measurements of the turbulence properties in the near wake of a circular cylinder at high Reynolds number by 2C-PIV and 3C-PIV. Exp Fluids 42:93–109

Perry AE, Chong MS, Lim TT (1982) The vortex shedding process behind two-dimensional bluff bodies. J Fluid Mech 116:77

Persillon H, Braza M, Williamson C (1997) Three-dimensional coherent structures in the flow around a circular cylinder by direct numerical simulation. In: Sorensen I, Hopnger E, Aubry N (eds) Simulation and identication of organised structures in flows, IUTAM symposium. Kluwer, Lyngby, Denmark, 25–28 May

Poncet P (2004) Topological aspects of three-dimensional wakes behind rotary oscillating cylinders. J Fluid Mech 517:27–53

Poncet P, Hildebrand R, Cottet J-H, Koumoutsakos P (2008) Spatially distributed control for optimal drag reduction of the flow past a circular cylinder. J Fluid Mech 599:111–120

Prasad AK, Jensen K (1995) Scheimpflug stereocamera for particle image velocimetry in liquid flows. Appl Optics 34(30):7092–7099

Roshko A (1961) Experiments on the flow past a circular cylinder at very high Reynolds number. J Fluid Mech 10:345

Scarano F (2002) Iterative image deformation methods in PIV. Meas Sci Technol 13:R1–R19

Scarano F, Riethmuller ML (2000) Advances in iterative multigrid PIV image processing. Exp Fluids 29:S51–S60

Scarano F, Elsinga GE, Bocci E and van Oudheusden BW (2006) “Investigation of 3-D coherent structures in the turbulent cylinder wake using Tomo-PIV”. 13th international symposium on applications of laser techniques of fluid mechanisms, Lisbon

Schrijer FFJ, Scarano F (2008) Effect of predictor–corrector filtering on the stability and spatial resolution of iterative PIV interrogation. Exp Fluids 45(5):927–941. doi:10.1007/s00348-008-0511-7

Schröder A, Geisler R, Staack K, Wieneke B, Elsinga GE, Scarano F, Henning A (2008) Lagrangian and Eulerian views into a turbulent boundary layer flow using time-resolved tomographic PIV. 14th international symposium on applications of laser techniques of fluid mechanisms, Lisbon

van Doorne C, Westerweel J (2007) Measurement of laminar, transitional and turbulent pipe flow using Stereoscopic-PIV. Exp Fluids 42:259–279

Westerweel J, Scarano F (2005) Universal outlier detection for PIV data. Exp Fluids 39:1096–1100

Wieneke B (2008) Volume self-calibration for 3D particle image velocimetry. Exp Fluids 45(4):549–556. doi:10.1007/s00348-008-0521-5

Willert C (1997) Stereoscopic digital particle image velocimetry for application in wind tunnel flows. Meas Sci Technol 8:1465–1479

Williamson CHK (1988) Defining a universal and continuous Strouhal-Reynolds number relationship for the laminar vortex shedding of a circular cylinder. Phys Fluids 31:2742

Williamson CHK (1995) Three-dimensional wake transition. J Fluid Mech 328:345–407

Williamson CHK (1996) Vortex dynamics in the cylinder wake. Annu Rev Flu Mech 28:477

Wu J, Sheridan J (1994) An experimental investigation of streamwise vortices in the wake of a bluff body. J Fluids Struct 8:621–625

Acknowledgments

The tomographic PIV system was kindly provided by LaVision GmbH. Bernd Wieneke is acknowledged for the support given on tomographic data analysis. Prof. Westerweel from the Laboratory for Aero and Hydrodynamics at TU Delft is acknowledged for his insightful comments on this study. This work is supported by the Dutch Technology Foundation STW, VIDI—Innovation Impulse grant DLR.6189.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material (AVI 18.8 mb)

Supplementary material (AVI 9.14 mb)

Supplementary material (AVI 11.7 mb)

Supplementary material (AVI 13.0 mb)

Supplementary material (AVI 13.6 mb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Scarano, F., Poelma, C. Three-dimensional vorticity patterns of cylinder wakes. Exp Fluids 47, 69–83 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00348-009-0629-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00348-009-0629-2