Abstract

In recent years, the management literature has increasingly investigated organizational ambidexterity—the ability to balance exploitative and explorative activities—as an important antecedent to firm survival and performance. Some recent studies indicate that management control systems may be able to foster organizational ambidexterity. The aim of the present short survey paper is to provide an overview of the current literature on organizational ambidexterity and management control systems. Overall, the results of the review show that rather than a single specific management control system, a package of management control systems and various forms of using such systems may be necessary to successfully achieve and manage organizational ambidexterity. In line with this notion, some of the included papers even find a complementary effect of the combined use of opposing management controls to support the achievement of organizational ambidexterity. The paper concludes with several specific ideas for further research.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Most contemporary organizations find rapid technological developments and political changes difficult to predict (e.g., Coeckelbergh 2012; Grant 2015). Thus, organizations must cope with a high level of uncertainty, adapting to new developments while carefully utilizing their resources to do so (e.g., Güttel and Konlechner 2009; Winter and Szulanski 2001). In line with the basic tenets of the resource-based view (Barney 1991; Barney et al. 2011; Wernerfeldt 1984), Simons (2010) therefore argues that organizations need to (i) exploit their existing resources to be able to generate revenues and earnings and (ii) explore new opportunities and resources, create innovations and adapt to arising changes.Footnote 1

In the literature, the simultaneous pursuit of and balance between exploitation and exploration is referred to as organizational ambidexterity (O’Reilly and Tushman 2013). Many studies show a positive correlation between organizational ambidexterity and the survival of organizations. O’Reilly and Tushman (2013), for instance, study the influence of organizational ambidexterity under uncertain conditions and find that higher survival rates, better financial performance and more innovation are clearly linked to organizational ambidexterity. In general, ambidextrous organizations seem to show better performance and greater competitiveness (Cao et al. 2009).

To develop and maintain an adequate balance between exploitation and exploration, the use of management control systems can be essential (McCarthy and Gordon 2011). Malmi and Brown (2008) and Guenther (2013) purport that management control systems influence the behavior of managers and employees. Similarly, Strauß and Zecher (2013) argue that strategic issues such as balancing exploratory and exploitative activities may also be pursued with the help of management control systems. Therefore, management control systems can further the exploitative as well as the exploratory behavior of employees in an organization.

Research has found that while many firms do not lack a focus on exploitation, they often invest too little time and resources into exploratory activities (Davis et al. 2009; Hill and Birkinshaw 2014; McNamara and Baden-Fuller 1999). However, an appropriate representation of ambidexterity objectives in a firm’s management control system may support the adequate pursuit of exploration activities, which, in turn, may help ensure an organization’s longer-term existence (Haustein et al. 2014; McCarthy and Gordon 2011).

Despite this apparent importance of management control systems for creating organizational ambidexterity, and ultimately firm survival and superior firm performance (Cao et al. 2009; O’Reilly and Tushman 2013), little research on how management control systems support and influence organizational ambidexterity has thus far been conducted. Nevertheless, some articles have been published on the relations between organizational ambidexterity and management control systems. This paper provides an overview of this body of the literature and proposes fruitful future research avenues. For this purpose, we systematically review the available papers on the topic. We use Malmi and Brown’s (2008) typology to classify the management control systems studied so far in relation to organizational ambidexterity. Our paper highlights that various management control systems, as well as combinations of management control systems, are able to facilitate organizational ambidexterity. At the same time, our review suggests that a more precise understanding of the relationship between management control systems and organizational ambidexterity—which would be needed to provide more concise recommendations for practice—requires more research investigating under which conditions and circumstances management control systems or combinations of such systems can foster organizational ambidexterity.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, a brief review of the background of organizational ambidexterity and its development over the past few decades is presented. In this vein, we pay special attention to the different types and ways of achieving organizational ambidexterity, such as structural and contextual ambidexterity. Section 3 describes the methods we applied to identify the relevant papers on organizational ambidexterity and management control systems. Section 4 summarizes the findings of our systematic analysis of these papers, and in Sect. 5, we propose some future research avenues. Section 6 provides a conclusion and draws together the most important aspects of this short survey paper.

2 Organizational ambidexterity

The term “organizational ambidexterity” was first used by Duncan (1976), who argues that organizations need to change their structures over time to enable innovation and efficiency. Although the simultaneous achievement of exploitation and exploration was argued to be impossible in early research, March (1991) proposes that organizations need to balance both exploitation and exploration to achieve long-term survival and success. Organizational ambidexterity means the simultaneous pursuit of exploratory and exploitative activities in an organization (O’Reilly and Tushman 2013). Whereas exploration describes the search, variation and discovery of new resources and experimentation with them, exploitation refers to the refinement, selection and implementation of resources with a focus on efficiency (Raisch and Birkinshaw 2008).

Although exploration and exploitation are often considered to be contradictory activities, several authors argue that they need to be pursued at the same time in a healthy balance to achieve organizational ambidexterity (March 1991; Raisch and Birkinshaw 2008; O’Reilly and Tushman 2013). Some authors even argue that under the right circumstances, exploratory and exploitative activities can be mutually enhancing. The aim, then, is to achieve high levels of both exploration and exploitation (Gupta et al. 2006).

The focus in many organizations is on exploitative activities because exploitation is associated with certainty, efficiency and short-term gains, whereas exploration is associated with uncertainty, inefficiency and costs (Hill and Birkinshaw 2014; O’Reilly and Tushman 2013). However, in conjunction with the proper levels of exploitative activities, exploratory activities can enhance the long-term performance of an organization (Cao et al. 2009). While organizations that focus only on exploitation may be able to increase their short-term revenues and earnings, they may not be able to keep up with the environmental and technological changes in their business sector. By contrast, although organizations that only focus on exploration may be able to adapt to changes and be innovative, they may not be able to gain returns on their invested capital (Raisch and Birkinshaw 2008). Indeed, the achievement of a healthy balance between exploration and exploitation is essential for the long-term survival and success of an organization. Many authors even argue that organizational ambidexterity is a precondition for organizational success and survival (Raisch and Birkinshaw 2008). Especially important, however, is to strike the right balance in a resource-constrained context because organizations must trade off exploration and exploitation (Cao et al. 2009).

Organizational ambidexterity can exist in different forms (Gibson and Birkinshaw 2004; Güttel et al. 2012). Birkinshaw and Gibson (2004) distinguish between structural and contextual ambidexterity. First, the concept of structural ambidexterity was established by Tushman and O’Reilly (1996). Based on Duncan’s (Duncan 1976) work, they describe the structural mechanisms that facilitate organizational ambidexterity. Structural ambidexterity means the separation of exploratory and exploitative activities through a dual structure in the organization. Different business units focus on either exploration or exploitation. The separation is often necessary because of the different nature of exploratory and exploitative activities (Birkinshaw and Gibson 2004). For instance, an organization might establish a structure in which the R&D and business development units are responsible for the exploration of new resources, markets and trends and the core business units are responsible for the exploitation of existing resources and markets (Birkinshaw and Gibson 2004). The advantage of such a structural separation is that employees have clearly defined goals and tasks. However, this separation also entails the risk of the isolation of the different tasks (Birkinshaw and Gibson 2004). Therefore, the continuous integration and transfer of knowledge between separate business units on exploratory and exploitative activities is of vital importance (McCarthy and Gordon 2011).

Second, the concept of contextual ambidexterity was developed by Gibson and Birkinshaw (2004). The concept was named contextual ambidexterity because in this case ambidexterity arises from characteristics of the organizational context (Güttel and Konlechner 2009; Güttel et al. 2015). Contextual ambidexterity means the integration and simultaneous pursuit of exploratory and exploitative activities in one business unit (Birkinshaw and Gibson 2004). This approach requires more flexible systems and structures that allow individual employees to decide on their own how much time they want to invest in exploratory or exploitative activities (Birkinshaw and Gibson 2004). For instance, ambidextrous employees are informed and act in the interest of the organization without the permission or support of superiors. Ambidextrous employees are motivated to adapt to new opportunities in line with the organization’s goals (Birkinshaw and Gibson 2004). This type of ambidexterity has the advantage that activities are integrated from the beginning and there is no risk of isolation (Birkinshaw and Gibson 2004). However, appropriate management control systems must be used to manage the behavior of employees and create an appropriate context that supports both exploratory and exploitative activities (McCarthy and Gordon 2011).

Despite the existence of these two forms of organizational ambidexterity, Birkinshaw and Gibson (Birkinshaw and Gibson 2004, p. 55) argue that “contextual ambidexterity isn’t an alternative to structural ambidexterity but rather a complement”. The separation of exploration and exploitation is sometimes necessary, but according to Birkinshaw and Gibson (2004), it should remain temporary. Raisch et al. (2009) argue that to sustain organizational ambidexterity over time, it may be necessary to apply structural as well as contextual solutions. The difficulty that organizations face is that exploration and exploitation may require different structures and skills and may be supported through different management control mechanisms (Simons 2010). The achievement of organizational ambidexterity can thus be influenced and supported through different means of and approaches to management control, as investigated in the following sections.

3 Identification and overview of relevant papers

To identify relevant papers on organizational ambidexterity and management control, a keyword search for academic journal articles in two electronic databases, namely EBSCO Business Source Premier and Scopus, was conducted. To be considered to be relevant for the present short survey paper, articles needed to address both management control or management control systems and organizational ambidexterity. In addition to this keyword search, the references of the articles found in the keyword search were also searched for additional articles on organizational ambidexterity and management control. For the inclusion of articles in this short survey paper, we imposed no restrictions concerning the publication date. However, papers without a clear relation to both management control and organizational ambidexterity were excluded. To judge whether articles dealt with organizational ambidexterity, we required the papers in question to examine either organizational ambidexterity or both basic activities leading to ambidexterity (i.e., exploration AND exploitation). Thus, papers concerning aspects of management control and only one of these two basic activities were not included in this review. This overall search process resulted in 16 relevant articles. Table 1 provides an overview of these articles.

The 16 papers on the topic used a variety of research designs to study the relations between organizational ambidexterity and management control. Table 2 summarizes the objectives and research questions as well as the main findings of the papers.

4 Organizational ambidexterity and management control

Although management control systems are traditionally perceived as instruments for the exploitation of existing resources, they can also be used to support the exploration of potential resources and new opportunities (Simons 2010). Malmi and Brown (2008) understand management control systems as a package consisting of various systems, further providing a typology of such systems. Malmi and Brown (2008) consider planning, cybernetic, reward and compensation, administrative and cultural controls to direct people’s behavior in a way that ensures alignment with the organization’s strategy and achievement of its objectives. To evaluate how management control systems can influence and support organizational ambidexterity, Malmi and Brown’s (2008) typology of management control was used to categorize the findings of the 16 identified papers.

Malmi and Brown’s (2008) framework is suitable for our purposes because it comprises an empirically grounded (e.g., Bedford and Malmi 2015; Bedford et al. 2016), comprehensive and well-structured overview of several types of management control systems. However, the Malmi and Brown (2008) framework is admittedly not the only available framework having these aspects and which might be used in categorizing prior literature. Alternative frameworks include, for instance, the Simons’s (1995) levers of control framework, its further development by Tessier and Otley (2012), or Ouchi’s (1979, 1980) framework of market, bureaucratic and clan controls. Nevertheless, we view the Malmi and Brown (2008) framework as better suited for categorizing various management control systems and their relations to organizational ambidexterity, because, of those available, this framework enables the most precise allocation of studies to types of control. Namely, it includes more detailed categories than the alternative frameworks by Simons (1995), Tessier and Otley (2012) or Ouchi (1979, (1980). Moreover, the Malmi and Brown framework has already proven useful in similar review papers on management control phenomena (e.g., Guenther et al. 2016; Hiebl 2014). Thus, the bottom line is that their typology also seems appropriate for our categorization and analysis of the various types of management control examined in the identified papers on organizational ambidexterity and management control.

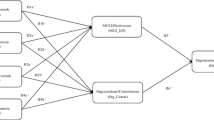

We categorized the findings of the 16 identified papers into the categories of Malmi and Brown (2008) where they fit the best from our point of view. Categorization of the findings was especially difficult for planning controls and cybernetic controls, since these are closely linked. As a guideline, we chose to categorize findings that concern goal setting under planning controls and those that concern control and feedback under cybernetic controls. Table 3 provides an overview of the categorization of the studied papers. The following subsections then highlight how five types of management control systems (Malmi and Brown 2008) influence an organization’s ability to achieve organizational ambidexterity. These five types of management control systems are (i) cultural controls, (ii) planning controls, (iii) cybernetic controls, (iv) reward and compensation controls and (v) administrative controls.

4.1 Cultural controls

Malmi and Brown (2008) argue that culture can be used to regulate behavior and can therefore serve as a control system. They consider value-based controls, symbol-based controls and clan controls as potential cultural controls (Malmi and Brown 2008). Of the relevant papers on management control and organizational ambidexterity, seven include forms of cultural controls in their analysis. Three of these papers, namely Mundy (2010), McCarthy and Gordon (2011) and Bedford (2015), are based on Simons’ (1995) “levers of control” framework. Malmi and Brown’s (2008) framework includes as cultural controls what Simons (1995) calls “belief systems”. However, Malmi and Brown’s (2008) understanding of cultural controls is more extensive, as they explain that cultural controls are not just used to communicate values, but can also be used to create a culture of communication and collaboration. Therefore, to some extent, what Simons (1995) views as interactive control systems is also captured in Malmi and Brown’s (2008) cultural controls.

The existing literature on cultural controls and organizational ambidexterity reveals that cultural controls can support exploration as well as exploitation in an organization and even balance these contradictory forces (Kang and Snell 2009; Mundy 2010; McCarthy and Gordon 2011; Ylinen and Gullkvist 2014). Mundy (2010) emphasizes that cultural controls are central for change as well as for retaining focus on an organization’s objectives. They can enable exploration by supporting “open channels of communication and [the] free flow of information” and by providing the necessary flexibility for organizations and their employees to react proactively to changes (Ylinen and Gullkvist 2014, p. 94). Jørgensen and Messner (2009) emphasize that it is important to build a culture of tolerance because when the organization aims for exploration, errors may occur. Therefore, to foster exploration, Jørgensen and Messner’s (2009) findings suggest that employees should not be punished for negative outcomes. In turn, by aligning the behavior of employees with the organization’s objectives and values and thus providing stability and orientation, McCarthy and Gordon (2011) argue that cultural controls can also enable exploitation.

To balance exploratory and exploitative activities, Kang and Snell Footnote 2 (2009) offer a combination of countervailing forces to create a complementary effect. They suggest that rule-following cultures that create a disciplined environment and foster exploitation can act as a counterpart to human and social capital that seeks exploration. In this case, cultural controls can ensure the integration and refinement of the arising variety (Kang and Snell 2009). In turn, cultural controls can also facilitate exploration through the encouragement of alternative interpretations and “creative problem solving”, which ensures the exploration of alternative solutions and therefore acts as a counterpart to human and social capital with an orientation to exploitation (Kang and Snell 2009, p. 76). Kang and Snell (2009) argue that this combination of countervailing forces creates a complementary effect and results in an orientation of behavior towards ambidextrous learning.

Two of the studies concerned with cultural controls investigate their effect on performance (Ylinen and Gullkvist 2014; Bedford 2015). Ylinen and Gullkvist (2014)Footnote 3 find that cultural controls have a positive indirect effect on exploratory innovation projects through the improvement of innovativeness and, consequently, performance. Ylinen and Gullkvist (2014) explain that cultural controls can support idea generation and thus drive innovativeness and facilitate exploration. However, they also find that cultural controls can have a positive influence on the performance of exploitative innovation projects, with the difference being that the effect influences performance directly rather than being mediated by idea generation, as is the case in exploratory innovation projects. Ylinen and Gullkvist (2014) argue that the different levels of uncertainty and need for new knowledge might explain the different effects of cultural controls.

Bedford (2015) investigates the use of management control systems and their effect on firm performance, finding the partially different results that cultural controls do not enhance firm performance in firms that focus on either exploration or exploitation. However, Bedford’s (2015) analysis further suggests that, in ambidextrous firms, greater reliance on cultural controls is positively associated with firm performance. Thus, following this analysis, cultural controls may be important vehicles for translating ambidexterity into superior firm performance.

So far, we have only discussed cultural controls as a group. However, the different types of cultural controls described by Malmi and Brown (2008) also find their expression in several of the analyzed papers (McCarthy and Gordon 2011; Kang and Snell 2009; Jørgensen and Messner 2009). Value controls, for instance, were examined by McCarthy and Gordon (2011, p. 252), who found that “company reports, mission statements and website pages” as well as the recruitment process and employee training are used to communicate the values and vision of the organization (and thus serve as value controls). Their interviews reveal that the architecture of buildings and decoration on the walls are supposed to inspire employees towards the exploration of new opportunities (and may thus serve as symbol-based controls). Symbol controls were also investigated by Jørgensen and Messner (2009), who emphasize the importance of a culture of tolerance, which in their case organization was expressed by the so-called “chamber of horrors” that contained unrealized ideas that were expensive mistakes. The managers in the case site were proud of this collection, because it served as a symbol for their efforts to challenge things and for the acceptance that sometimes failure is part of getting somewhere (Jørgensen and Messner 2009).

Clan controls were also studied by McCarthy and Gordon (2011). They mention that the values and vision installed according to the profession as well as socialization events are used to build organizational coherence (which may be interpreted as clan controls). McCarthy and Gordon (2011) argue that all the examples of cultural controls are used to inspire employees to explore and enable feed-forward control, which in combination with other management controls contributes to the achievement of organizational ambidexterity.

Pointing to the risks of not sufficiently considering cultural controls, Selcer and Decker’s (2012) study demonstrates the power of cultural controls and finds that ignoring or failing to manage cultural controls can hamper the organization severely. In their case study, top managers paid too little attention to patterns of communication and existing behaviors and practices. Selcer and Decker (2012) conclude that the case organization could not achieve organizational ambidexterity because the unwritten norms and meanings constructed by employees were not identified, and thus top managers’ control tactics failed. This negative example, however, also points to the notion that cultural controls may be important antecedents to the achievement of organizational ambidexterity.

In summary, these insights show that cultural controls can have a powerful influence on achieving organizational ambidexterity. Cultural controls enable informal control through effective social norms and can thereby partially substitute for formal controls and balance exploitation and exploration in an organization (McCarthy and Gordon 2011; Bedford 2015). Ignoring the power of cultural controls for achieving high levels of ambidexterity may have detrimental effects (Selcer and Decker 2012). In particular, the combination with other management control systems can support the achievement of organizational ambidexterity (Kang and Snell 2009; McCarthy and Gordon 2011). The collective evidence in the literature, however, suggests that cultural controls are especially suited for fostering exploration, while exploitation may also be achieved through more formal types of control.

4.2 Planning controls

Planning directs behavior and effort by providing standards and goals. The planning process allows for the coordination of goals throughout the organization and ensures the alignment of activities with the organization’s strategy (Malmi and Brown 2008). Malmi and Brown (2008) distinguish between action planning and long-range planning. In their view, action planning has a tactical focus and concerns actions and goals within 12 months, whereas long-range planning has a strategic focus and concerns actions and goals in the medium and long run.

Three of the four reviewed papers that examine planning controls, namely those by Mundy (2010), McCarthy and Gordon (2011) and Bedford (2015), are based on Simons’ (1995) levers of controls framework. Similar to Malmi and Brown’s (2008) planning controls, Simons’ (1995) interactive control lever focuses on planning activities and on challenging the assumptions that form the basis of an organization’s activities. Therefore, interactive and planning controls can be regarded as similar forms of control, which is why in the following we only use Malmi and Brown’s (2008) term “planning controls”.

The reviewed papers suggest that planning controls can support the achievement of organizational ambidexterity because—depending on their use—they are able to foster both exploration and exploitation and may also be used to balance these two modes (Mundy 2010; McCarthy and Gordon 2011). Bedford (2015) argues that planning controls are used to constantly challenge existing action plans by facilitating open debate at any time, thus supporting exploration. To facilitate a feed-forward orientation, McCarthy and Gordon (2011) suggest the use of planning controls in combination with cultural controls, which support exploration by facilitating employees’ ability to proactively scan and plan to recognize change. However, planning controls are also used to communicate strategic objectives to employees. These objectives may serve as guidelines for action planning, which helps ensure the organization focuses on its overall objectives and, in turn, facilitates exploitation (Mundy 2010; McCarthy and Gordon 2011).

According to Ahrens and Chapman (2004), planning controls foster interaction and thus allow for a combination of knowledge and information on different individuals. According to their case analysis, planning controls can therefore allow the use of local knowledge to develop plans, which may be an important ingredient for explorative activities. However, Mundy (2010) warns that planning controls, which allow too much interactive processes, can destabilize an organization by causing continuous change. Nevertheless, Mundy (2010) emphasizes that strategic plans have to be challenged to be able to recognize a need for change. Therefore, Mundy (2010) argues for the use of countervailing controls to achieve organizational ambidexterity. In particular, Mundy (2010) suggests the combination of planning controls, which allow interactive processes and foster exploration, and cybernetic controls, which provide measures and control over the achievement of planned goals and ensure sufficient exploitation. Similarly, Bedford’s (2015) study shows the close link between planning and cybernetic controls. He finds that an emphasis on planning controls in exploratory innovation firms has a positive effect on performance. Further, his study reveals that the simultaneous use of planning controls and cybernetic controls has a positive influence on firm performance. However, he also finds that an imbalance between planning controls and cybernetic controls influences the performance of ambidextrous firms negatively.

In summary, our analysis suggests that planning controls may be used for both exploitation and exploration. According to McCarthy and Gordon (2011) and Bedford (2015), planning controls that serve the information of employees, integration of knowledge and feed-forward control orientation can be beneficial to exploration because they can provide the basis for open communication and discussion of current action plans, therefore enabling employees to recognize arising changes. In turn, planning controls that merely focus on action planning and constraining the activities of employees further exploitation by focusing the behavior of employees on the organization’s objectives and limiting their freedom of action (McCarthy and Gordon 2011). Thus, to achieve organizational ambidexterity, a combination of countervailing management controls—such as planning controls and cybernetic controls—is suggested to balance exploration and exploitation (Bedford 2015; Mundy 2010).

4.3 Cybernetic controls

Cybernetic controls direct behavior by setting targets, measuring activities and assigning accountability for performance (Malmi and Brown 2008). Thus, they can be perceived as being similar to Simons’ (1995) diagnostic control lever. Malmi and Brown (2008) identify budgets, financial measures, non-financial measures and combinations of both financial and non-financial measures as basic cybernetic systems.

Several authors of the reviewed papers argue that cybernetic controls are typically used to ensure exploitation (Bedford 2015; McCarthy and Gordon 2011; Mundy 2010). For instance, Bedford’s (2015) study shows that in exploitative innovation firms an emphasis on cybernetic controls has a positive effect on performance. However, some argue that cybernetic controls can also facilitate exploration if used in an enabling way, and can therefore help balance exploration and exploitation (Bedford 2015; Grafton et al. 2010; Mundy 2010). Cybernetic controls can be used to make the organization’s goals and performance transparent, thus enhancing the commitment of employees and focusing their actions on the desired outcomes (Jørgensen and Messner 2009; McCarthy and Gordon 2011; Bedford 2015). Bedford (2015) explains that on the one hand, cybernetic controls provide clear objectives that have to be achieved, which supports exploitation. On the other hand, they do not specifically define how to achieve the set objectives, thereby providing room for exploration and facilitating the achievement of organizational ambidexterity. To support exploitation, McCarthy and Gordon (2011) suggest that a combination of cybernetic controls and administrative controls could limit the activities of employees and help analyze their performance.

As indicated in Section 4.2, Bedford (2015) and Mundy (2010) find that organizations benefit from the combined use of planning and cybernetic controls in the pursuit of organizational ambidexterity. According to Bedford (2015) and similar to the basic arguments brought forward by Simons (1995), the interplay between interactive planning activities and cybernetic controls can create a dynamic tension that supports organizations confronted with contradictory forces, such as the simultaneous pursuit of exploration and exploitation and the achievement of organizational ambidexterity. However, to maintain organizational ambidexterity, cybernetic controls need to be used with care. Too much emphasis on cybernetic controls can hinder innovation and endanger the balance between exploration and exploitation (Mundy 2010).

In line with this notion, Grafton et al. (2010)Footnote 4 find that, depending on their use, cybernetic controls can support exploitation as well as exploration. According to their analysis, decision-facilitating measures used for feedback control support exploitation, whereas decision-facilitating measures used for feed-forward control support exploration. Grafton et al. (2010) suggest that to achieve organizational ambidexterity, it is necessary to find a balance in the employment of performance measures. They argue that evaluation can be a powerful control instrument to direct the behavior of employees and that decision-facilitating measures should be used for evaluations to a greater extent. The authors further argue that this can support organizational ambidexterity in an organization and give higher-level managers the ability to direct employee behavior to focus on the long-term effects of their actions.Footnote 5

According to Schermann et al. (2012), the use of integrated information systems can increase an organization’s ability to perceive weak signals and thus improve its ability to react to these early warnings in time, thereby avoiding the negative consequences and taking advantage of the positive effects. Therefore, the use of integrated information systems can improve an organization’s exploratory management control activities. Schermann et al. (2012) further find that integrated information systems are able to provide an integrated database, ensure permanent monitoring and permit the creation of individual dashboards, which allow users to create a coherent set of information adapted to their needs. Therefore, integrated information systems enable the organization to simultaneously use exploratory and exploitative management control activities and support the achievement of organizational ambidexterity (Schermann et al. 2012).Footnote 6

Collectively, these insights suggest that the use of cybernetic controls can further the achievement of organizational ambidexterity by influencing the balance between exploitative and exploratory forces. The use of cybernetic controls for both feed-forward and feedback control provides orientation and enables an organization to balance exploration and exploitation. The authors of the reviewed papers emphasize the careful use of cybernetic controls to, on the one hand, be able to provide transparency and guidance through different performance measures and, on the other hand, leave enough space for employees to find new ways in which to solve problems and motivate them to achieve their goals (Bedford 2015; Grafton et al. 2010; Mundy 2010; Schermann et al. 2012).

4.4 Reward and compensation controls

Reward and compensation controls aim to establish congruence between the goals of the organization and those of employees by motivating them by means of, for instance, bonus payments (Malmi and Brown 2008). Our review includes five studies that consider reward and compensation controls. McCarthy and Gordon (2011) suggest that feedback information from cybernetic controls is used to reward the behavior of employees, which is supposed to motivate them and align their activities with the organization’s objectives. This aims to enforce conformance and correct deviations and therefore serves exploitation. Similarly, Kang and Snell (2009) find that reward and compensation controls that aim for “error avoidance” use behavior-based rewards as well as behavior appraisal systems and support exploitation by ensuring that employees are doing what is planned and expected of them. However, Kang and Snell (2009) argue that reward and compensation controls can also support exploration by using an “error embracing” control system and developmental performance appraisal.

In a similar vein, Grafton et al. (2010) explain that reward systems can result in employees focusing their efforts on those measures used for their evaluation and not on those that would be most appropriate, which can endanger the achievement of the organization’s objectives. Further, because most evaluation systems focus on financial measures, this can hinder the achievement of organizational ambidexterity. Similarly, Mundy (2010) describes how cybernetic systems coupled with a reward system can bring employees into a dilemma. Employees may have to decide to act against their better knowledge to achieve a goal and get a reward or deviate from the expected behavior in order to prevent a negative outcome in the long run and thus lose their reward. Hence, such reward systems can be effective in achieving short-term gains, but can undermine long-term performance (Mundy 2010).

Medcof and Song (2013) find that the performance-compensation linkage is more formal in exploitative human-resource configurations than in exploratory human-resource configurations. Further, they hypothesized that reduced formalization facilitates greater improvisation in exploratory contexts. However, they also find that less formalization in this context still leads to disadvantages in terms of reduced “process transparency, developmental feedback, performance-compensation linkage strength and training available” (Medcof and Song 2013, p. 2921). They argue that in exploitative contexts with stable tasks, human resource systems can be highly formalized. For more dynamic contexts, such as exploratory human resource configurations, formalized systems are less functional and adjustments are necessary. Medcof and Song (2013) explain that reward and compensation controls should be adapted to context and purpose, balancing the costs and benefits of reward and compensation controls.

Therefore, it can be concluded that reward and compensation controls can influence the balance of exploration and exploitation and support the achievement of organizational ambidexterity (Kang and Snell 2009; McCarthy and Gordon 2011). However, the reviewed papers concordantly warn that reward and compensation controls have to be used carefully. They present evidence that such controls are not always appropriate for meeting the underlying organizational objectives, as they can have a distorting influence and thus can endanger the achievement of organizational ambidexterity (Grafton et al. 2010; Mundy 2010).

4.5 Administrative controls

Malmi and Brown (2008) argue that administrative controls can direct employee behavior by organizing and monitoring behavior and by determining responsibilities and the conduct of processes. Malmi and Brown (2008) distinguish between organizational structure, governance structure and procedures and policies. Our review includes 14 studies that include some forms of administrative controls according to Malmi and Brown’s (2008) typology. As indicated above, some of the reviewed papers originally drew on Simons’ (1995) levers of control framework. Simons’ (1995) boundary control lever is characterized as determining the acceptable extent of organizational activities by formal mechanisms and thus can be seen as similar to Malmi and Brown’s (2008) administrative controls (indeed, we integrate studies focused on Simons’ (1995) boundary control lever in this section with those on administrative controls).

Similar to the other four basic types of control systems as set out by Malmi and Brown (2008), the reviewed literature suggests that administrative controls can influence the achievement of organizational ambidexterity by balancing exploratory and exploitative activities (Bedford 2015; McCarthy and Gordon 2011). For instance, Schermann et al. (2012) find that integrated information systems can provide the basis for informed decisions and well-designed organizational procedures—which are essential parts of administrative controls—and thus contribute to the achievement of organizational ambidexterity.Footnote 7 McCarthy and Gordon (2011) and Bedford (2015) suggest that administrative controls provide structures that restrain and direct employees’ behavior by limiting activities and search spaces and by providing standardized ways of communication, thus supporting exploitation. In line with this notion, Bedford’s (2015) study shows that in exploitative innovation firms, an emphasis on administrative controls is positively associated with performance. At the same time, however, Bedford (2015) reports that administrative controls can also be beneficial to exploration because the provided structure can give employees the necessary flexibility to explore and help focus innovation activities, making them more efficient, which supports the realization of arising opportunities.

Similarly, Breslin (2014)Footnote 8 finds that a certain level of management control at all times is of vital importance for ambidextrous organizations. By applying Breslin’s (2014) findings, to direct employee behavior in the interest of the organization, administrative controls can be designed tightly in times of exploitation, whereas in times of exploration, they can be designed loosely but still able to ensure alignment with the organization’s objectives. Breslin (2014) finds that applying management controls, especially administrative controls, and allowing individuals and groups to adapt to changes and their proximity to customers can influence their behavior and actions in favor of either exploratory or exploitative activities. The author argues that a general direction of change has to be provided at all times to prevent chaotic conditions, thus enabling organizational ambidexterity and ensuring the long-term success and indeed survival of an organization.

In line with Breslin’s (2014) findings, Selcer and Decker (2012) describe an organization that employs the loose-tight principle, which constitutes of a combination of strict controls with strong autonomy and innovation, to achieve organizational ambidexterity. They argue that the organization both uses central controls to keep a watch on critical activities and takes risks by allowing autonomy, thereby creating managed chaos. Mundy (2010) argues that by maintaining overall control, administrative controls prevent employees from wasting an organization’s resources. Mundy (2010) further points out that cybernetic and administrative controls are mutually reinforcing by providing guidelines and targets and thus emphasizes the importance of a focus on long-term exploration and the danger of the dominance of short-term performance.

Ylinen and Gullkvist (2014)Footnote 9 argue that tight administrative controls can increase the performance of innovation projects through the interaction with loose cultural controls. They find that the combined use of such opposing controls can produce a complementary effect and enhance the performance of innovative projects. Administrative controls provide a certain level of stability and direction for innovation projects, which in combination with cultural controls lead to improved results and organizational ambidexterity (Ylinen and Gullkvist 2014). Kang and Snell (2009) also suggest that the achievement of organizational ambidexterity requires the combination of countervailing forces. Kang and Snell (2009)Footnote 10 argue that administrative controls are used to reinforce efficient coordination, therefore supporting exploitation. They further suggest that administrative controls can act as a counterpart to human and social capital that is oriented towards exploration. However, they state that in different situations, administrative controls, which provide simple rules and routines and enabling structures, may also support exploration and thereby act as a counterpart to human and social capital that seeks exploitation. They add that to combine countervailing forces in this way can result in a complementary effect and enable ambidextrous learning.

Although most authors argue that routines provide stability and are somewhat resistant to change (Bedford 2015; McCarthy and Gordon 2011), Feldman and Pentland (2003) argue that organizational routines can allow or even drive change. They claim that a process of selection and retention influenced by the subjective perception of employees takes place in routines, which then generates variety and leads to change. Correspondingly, Jørgensen and Messner (2009) find that structures can enable organizational ambidexterity by providing a clear process for new product development. Such a process may benefit from determined milestones to maintain a certain level of efficiency and enable flexibility in between. A formal structure forces employees to reflect on their activities and objectives and prevents them from exploring in too many directions without a focus (Jørgensen and Messner 2009). Ahrens and Chapman (2004) add that it is important for a successful use of administrative controls to convey a positive attitude towards employees, motivating them to work with the administrative controls and to use them for their benefit.

Similarly, Simons’ (2010)Footnote 11 study focuses on a control system based on accountability and control. He argues that depending on the regulation of span of control and span of accountability, administrative controls can be used to direct the behavior of employees in favor of either exploration or exploitation and can therefore be used to support the achievement of organizational ambidexterity. According to Simons (2010), the alignment of span of control and span of accountability supports exploitation in an organization; however, an “entrepreneurial gap”Footnote 12 influences the behavior of employees in favor of exploration activities (p. 14).

Fang et al. (2010) and Simons (2010) both emphasize the importance of semi-isolated subgroups in the achievement of organizational ambidexterity. Fang et al. (2010) argue that a structure of semi-isolated subgroups can preserve the variety of knowledge, thereby enabling exploration. The interaction between these subgroups spreads novel knowledge, thus facilitating exploitation (Fang et al. 2010). Simons (2010) adds that the creation of the above-described “entrepreneurial gap” can help stimulate interaction and cooperation between isolated business units because the scarcity of controlled resources in a business unit makes this necessary to achieve the set objectives. Interaction and cooperation between separate business units seems especially important for organizations that desire structural ambidexterity (McCarthy and Gordon 2011).

Finally, Siggelkow and Levinthal (2003) emphasize the advantages of the temporal sequencing of different organizational structures and argue that organizations that use temporary decentralization followed by reintegration are able to free themselves from their current practices and assumptions. They further argue that such organizations can therefore achieve organizational ambidexterity. In their simulation study, Siggelkow and Levinthal (2003) also find that decentralization enables exploration by creating cross-interdependencies and preventing divisions from becoming stuck with their own assumptions. Eventually, they show that exploitation is enabled by the refinement of solutions and coordination across different divisions.

These insights suggest that a certain level of administrative controls that provides the basic structure of the organization is essential for firm survival and the achievement of organizational ambidexterity at all times (Bedford 2015). Administrative controls can further exploitation as well as exploration, as both need a basic structure. Exploitation can be supported by tight structures providing standardized procedures, limiting the behavior of employees and increasing predictability, whereas exploration can be supported by structures that focus on the search for and realization of opportunities but also allow flexibility (Bedford 2015; Breslin 2014; Kang and Snell 2009; McCarthy and Gordon 2011). Similar to our findings on the other control types, these insights indicate that the combined use of opposing controls may be most beneficial to the achievement of organizational ambidexterity (Bedford 2015; Breslin 2014; Ylinen and Gullkvist 2014). It can further be concluded that different organizational structures can be leveraged to manage the tension between exploration and exploitation successfully (Fang et al. 2010; Siggelkow and Levinthal 2003; Simons 2010).

5 Further research avenues

In summary, our review has shown that all basic forms of management control as categorized by Malmi and Brown (2008) can be valuable in achieving high levels of organizational ambidexterity. From the current literature, it appears that none of these forms of management control would be restricted to either exploration or exploitation. It rather seems that the usage and combinations of these varying forms of control point to either exploration or exploitation. Whereas management control systems that motivate employees to act creatively and that leave them some freedom of action are viewed as fostering exploration, the more restrictive and diagnostic use of management controls seems to support exploitation. Thus and as argued by most of the authors of the papers reviewed, in order to reach high levels of organizational ambidexterity, combinations of various forms of management control systems are needed. This is why our findings may also be read as evidence that an interrelated usage of various management control systems is necessary in order to reach ambidexterity. Thus, there may be dependencies between these systems in line with the notion that there are systematic relationships between various management control systems (e.g., Bedford and Sandelin 2015; Bedford et al. 2016; Grabner and Moers 2013).

Based on the results of this review, several directions for further research appear fruitful. These research avenues can be relevant for both future research and management practice, as they can provide relevant insights into how to use management control systems for the simultaneous pursuit of exploration and exploitation. Our review suggests that various forms of management controls can be used to facilitate exploitation, exploration or both, thus reaching organizational ambidexterity. However, in order to gain a more precise understanding of these relationships and thus to arrive at more precise recommendations for practice, we generally need a better understanding of how exactly and under which conditions certain management control systems foster exploration, exploitation or both.

For instance, several authors argue that cultural controls can support exploration as well as exploitation and therefore support a balance (Bedford 2015; McCarthy and Gordon 2011; Mundy 2010); however, it remains unclear if cultural controls are capable of supporting exploration and exploitation at the same time or under which conditions such controls are able to do so. It might also be the case that countervailing influences of other management control systems are necessary in combination with cultural controls in order to reach ambidexterity. Therefore, further research might shed more light on the impacts of cultural controls on the balance of exploration and exploitation. Further research could investigate the following questions:

-

Can cultural controls support exploration and exploitation at the same time and achieve a balance? If so, how and under what circumstances?

-

Do cultural controls need opposing control mechanisms to facilitate organizational ambidexterity? If so, why and under which conditions?

-

Might the impact of management control systems on ambidexterity be mediated by organizational culture? If so, how and in which circumstances?

In the field of planning controls, further research could be conducted on how strategic goals and therefore long-range planning influence, firstly, the direction of attention and resources towards “different types of control systems” and, secondly, the achievement of organizational ambidexterity (McCarthy and Gordon 2011, p. 254; Malmi and Brown 2008). McCarthy and Gordon (2011) emphasize that with the use of different management control systems, potential conflicts that may arise with long-range planning and different strategic goals can be solved. This could have a positive impact on organizational ambidexterity. As McCarthy and Gordon (2011) suggest, the conflict-solving potential of the use of different management control systems could therefore be investigated in the future. The following research questions might be fruitful:

-

To what extent have organizations included conflicting strategic goals in their control systems and what effects do these conflicts have on organizational ambidexterity?

-

What influence has the conflict-solving potential of the use of different management control systems on the achievement of organizational ambidexterity? Under which conditions can such conflict-solving potential be realized?

Mundy (2010) argues that the interactive use of planning controls and long-term cybernetic planning processes may be suppressed by other management control systems and short-term controls. Further research is therefore needed to explore the impacts of such suppression on achieving and maintaining high levels of organizational ambidexterity. At the same time, it would be interesting to examine in which situations such suppression is more or less likely to materialize. The following research questions might be investigated:

-

How does the suppression of different management control systems affect achieving and maintaining organizational ambidexterity?

-

In which situations and under which conditions are planning and long-term cybernetic controls suppressed by management controls focused on the short-term? What effect does such temporal suppression have on the ability to reach high levels of organizational ambidexterity?

Schermann et al. (2012) suggest that the use of integrated information systems can improve the measurement of cybernetic controls. Further research might investigate whether the improved measurement of cybernetic controls can support the use of decision-facilitating measures for feed-forward and feedback control and influence the balance between exploration and exploitation positively, as suggested by Grafton et al. (2010). Several papers also recommend a combination of different management control systems to achieve organizational ambidexterity (Mundy 2010; Bedford 2015). It might therefore be interesting for future research to further investigate the interdependencies between different management control systems and the influence on organizational ambidexterity. Specific research questions could include the following:

-

Can the improved measurement of cybernetic controls support the use of decision-facilitating measures and affect the balance between exploration and exploitation? If so, how and in which circumstances?

-

How do different management control systems interact and how do the interdependencies between different management control systems influence the ability to reach high levels of organizational ambidexterity?

-

Which conditions make a combined use of different management control systems more likely to have a positive effect on organizational ambidexterity and which conditions instead restrict such positive effects?

Only five studies included in our review—namely McCarthy and Gordon (2011), Kang and Snell (2009), Grafton et al. (2010), Medcof and Song (2013) and Mundy (2010)—concern reward and compensation controls. With the exception of Medcof and Song (2013), who analyze human-resource systems that included reward and compensation controls with a focus on the degree of formalization, none of the studies provides sufficient specific empirical data. Hence, it might be rewarding to empirically investigate the potential of organizations to influence the achievement of organizational ambidexterity through reward and compensation controls. Further, it might be beneficial to combine these insights with theoretical frameworks on reward and compensation controls. Future research could investigate the following questions:

-

To what extent can reward and compensation controls influence the achievement of organizational ambidexterity?

-

How and in which circumstances can organizations use reward and compensation controls to achieve organizational ambidexterity?

Three of the reviewed studies (McCarthy and Gordon 2011; Kang and Snell 2009; Ylinen and Gullkvist 2014) argue that the optimal balance of exploration and exploitation may change over time depending on factors such as environmental and economic conditions. Therefore, we suggest investigating how organizations can use different management control systems and mechanisms to dynamically alter the balance between exploration and exploitation over time to maintain organizational ambidexterity. Similarly, it would also be valuable to examine how managers find the optimal balance of management control systems to facilitate organizational ambidexterity. In this vein, it might be especially relevant for practice to determine indicators that help managers recognize if they have achieved such a balance (Mundy 2010). Future research questions might therefore include:

-

How and in which conditions can organizations use different management control systems to dynamically alter the balance between exploration and exploitation over time?

-

How can managers find the optimal balance of management control systems to facilitate organizational ambidexterity and how can they recognize or measure such an optimal balance?

6 Conclusions

The aim of the present short survey paper was to provide an overview of the literature on organizational ambidexterity and management control systems. In general, our review results provide some support for the notion expressed by McCarthy and Gordon (2011) that it seems necessary to use a wide range of management control systems to manage exploitation and exploration successfully, which supports the basic notion of the “management control as a package” approach of Malmi and Brown (2008). Indeed, six of the studies included in the review find that the use of opposing management controls can produce a complementary effect and can support the achievement of organizational ambidexterity (Mundy 2010; McCarthy and Gordon 2011; Breslin 2014; Ylinen and Gullkvist 2014; Kang and Snell 2009; Bedford 2015). However, besides various forms of controls, it seems to be no less important to vary how and in which conditions various controls are used to enable sufficient exploration and exploitation and thus reach organizational ambidexterity.

Our categorization of the research on management control and organizational ambidexterity, which was based on Malmi and Brown’s (2008) typology, shows that for some types of management control systems such as administrative controls, a series of studies has already been conducted. On the contrary, the relationship between organizational ambidexterity and other types of control systems (e.g. rewards and compensation controls) has received only limited scholarly attention. Therefore, it is our hope that the further research avenues highlighted in this paper inspire some future research on the important relation between management control systems and an organization’s ability to reach high levels of ambidexterity. Investigating these relationships not only should be of academic interest but it is also likely to yield valuable practical advice on how to use management control systems for the simultaneous pursuit of exploratory and exploitative activities.

Our review is subject to certain limitations. It includes 16 relevant papers on organizational ambidexterity and management control. However, despite an extensive literature search, we cannot guarantee that we have not overlooked any relevant work on these topics because, for example, other studies may have used different labels than our keywords. We tried to circumvent this possibility by not only relying on a keyword search, but also analyzing the references and citations of the initially identified papers. Furthermore, some studies included in our review did not use the term “organizational ambidexterity” or were not based on Malmi and Brown’s (2008) categorization of management control systems. Thus, we had to “translate” their findings into our framework. Of course, such a translation involves the limitation that other authors may have translated such studies’ findings differently and would therefore arrive at different conclusions than we did.

Notes

For clarity at the outset, in this paper we follow Barney’s (1991, p. 101) definition, viewing resources as “all assets, capabilities, organizational processes, firm attributes, information, knowledge, etc. controlled by a firm that enable the firm to conceive of and implement strategies that improve its efficiency and effectiveness”.

Kang and Snell (2009) investigate the mechanisms of organizational learning and its contribution to the achievement of organizational ambidexterity. They suggest that the management of intellectual capital is an important step to simultaneously pursue exploration and exploitation.

Ylinen and Gullkvist (2014) focus on the influence of mechanistic and organic control types on the performance of exploratory and exploitative innovation projects. Ylinen and Gullkvist (2014, p. 94) describe mechanistic controls as “relying on formal rules, standardized operating procedures and routines” and thus can be seen as equal to administrative controls. Organic controls are characterized as “flexible, responsive, informal control reflecting norms of cooperation communication and emphasis on getting things done and open channels of communication and free flow of information” and thus can be seen as equal to cultural controls (Ylinen and Gullkvist 2014, p. 94).

Grafton et al. (2010) address the problem of the suboptimal use of performance measurement systems by managers whose decisions are influenced by the orientation of the measures used for their evaluation. They find that financial measures are important in evaluations and thus are the predominant decision-influencing measures, whereas non-financial and customer-focused measures have a decision-facilitating role. The findings show that the use of decision-facilitating performance measures for feedback and feed-forward control is more likely if they are perceived to be used in the evaluation of the manager’s performance (Grafton et al. 2010). This gives the organization the ability to influence the manager’s behavior and decisions by altering the measures used to evaluate his/her performance according to the organization’s objectives. As a result, managers can support the achievement of organizational ambidexterity (Grafton et al. 2010).

The classification as cybernetic controls can be explained by the five types of performance measures identified by Grafton et al. (2010): aggregate financial, disaggregate financial, customer-focused, internal process and people learning and growth. These performance measures correlate with the financial, non-financial and hybrid measurement systems that Malmi and Brown (2008) identify as cybernetic controls.

The approach of Schermann et al. (2012) can be classified under cybernetic controls and administrative controls in Malmi and Brown’s (2008) framework. Continuous measurement in combination with the earlier recognition of chances and risks by using an integrated information system can lead to an improvement of cybernetic controls (Schermann et al. 2012; Malmi and Brown 2008). Budgets and financial measurement systems as well as non-financial and hybrid measurement systems, such as the detection of risks and chances, can be measured more efficiently and in real time, which helps balance exploitative and exploratory management control activities and supports the achievement of organizational ambidexterity (Schermann et al. 2012; Malmi and Brown 2008).

This relates to Malmi and Brown’s (2008) policies and procedures, which seek to influence the behavior of employees through standard operating procedures and behavioral constraints. The objective of exploitative management controls is to align the behavior of employees with an organization’s objective to ensure organizational performance. The notion that Schermann et al. (2012) describe corresponds to Malmi and Brown’s (2008) organizational structure, which also seeks to reduce the variance in employees’ behavior to increase its predictability and thereby supports exploitation. Schermann et al. (2012) explain further that part of the objective of exploratory controls to ensure organizational integrity is to support decision-making through the automated processing of information, thereby relating to Malmi and Brown’s (2008) governance structure, which depends on a well-structured basis to make informed decisions and thus can support organizational ambidexterity.

Ylinen and Gullkvist (2014) explain that mechanistic controls provide clear standards, formal rules and strict routines, thus determining the basic conditions for employees in an organization and influencing their behavior. Accordingly, the mechanistic controls investigated by Ylinen and Gullkvist (2014) can be categorized as administrative controls.

Kang and Snell (2009) argue that mechanistic capital consists of standardized processes and structures and detailed routines, which can be classified as administrative controls.

Simons (2010) seeks to answer the questions of whether the balance between exploration and exploitation varies and whether the organizational structure can influence an individual’s behavior.

According to Simons (2010), an “entrepreneurial gap” means that the span of control is narrower than the span of accountability.

References

Ahrens, T., & Chapman, C. S. (2004). Accounting for flexibility and efficiency: A field study of management control systems in a restaurant chain. Contemporary Accounting Research, 21(2), 271–301.

Adler, P., & Borys, B. (1996). Two types of bureaucracy: Enabling and coercive. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41(1), 61–90.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120.

Barney, J. B., Ketchen, D. J., & Wright, M. (2011). The future of resource-based theory: Revitalization or decline? Journal of Management, 37(5), 1299–1315.

Bedford, D. S. (2015). Management control systems across different modes of innovation: Implications for firm performance. Management Accounting Research, 28, 12–30.

Bedford, D. S., & Malmi, T. (2015). Configurations of control: An exploratory analysis. Management Accounting Research, 27, 2–26.

Bedford, D. S., Malmi, T., & Sandelin, M. (2016). Management control effectiveness and strategy: An empirical analysis of packages and systems. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 51, 12–28.

Bedford, D. S., & Sandelin, M. (2015). Investigating management control configurations using qualitative comparative analysis: an overview and guidelines for application. Journal of Management Control, 26(1), 5–26.

Birkinshaw, J., & Gibson, C. (2004). Building ambidexterity into an organization. Sloan Management Review, 45(4), 47–55.

Breslin, D. (2014). Calm in the storm: Simulating the management of organizational co-evolution. Futures, 57, 62–77.

Cao, Q., Gedajlovic, E., & Zhang, H. (2009). Unpacking organizational ambidexterity: Dimensions, contingencies, and synergistic effects. Organization Science, 20(4), 781–796.

Coeckelbergh, M. (2012). Moral responsibility, technology, and experiences of the tragic: From Kierkegaard to offshore engineering. Science and Engineering Ethics, 18(1), 35–48.

Davis, J. P., Eisenhardt, K. M., & Bingham, C. B. (2009). Optimal structure, market dynamism, and the strategy of simple rules. Administrative Science Quarterly, 54(3), 413–452.

Duncan, R. (1976). The ambidextrous organization: Designing dual structures for innovation. In R. H. Killman, L. R. Pondy, & D. Slevin (Eds.), The Management of Organization (Vol. 1, pp. 167–188). New York: North Holland.

Fang, C., Lee, J., & Schilling, M. A. (2010). Balancing exploration and exploitation through structural design: The isolation of subgroups and organizational learning. Organization Science, 21(3), 625–642.

Feldman, M. S., & Pentland, B. T. (2003). Reconzeptualizing organizational routines as a source of flexibility and change. Administrative Science Quarterly, 48(1), 94–118.

Gibson, C. B., & Birkinshaw, J. (2004). The antecedents, consequences and mediating role of organizational ambidexterity. Academy of Management Journal, 47(2), 209–226.

Grabner, I., & Moers, F. (2013). Management control as a system or a package? Conceptual and empirical issues. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 38(6–7), 407–419.

Grafton, J., Lillis, A. M., & Widener, S. K. (2010). The role of performance measurement and evaluation in building organizational capabilities and performance. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 35(7), 689–706.

Grant, R. M. (2015). Contemporary strategy analysis. Chichester: Wiley.

Guenther, E., Endrikat, J., & Guenther, T. W. (2016). Environmental management control systems: A conceptualization and a review of the empirical evidence. Journal of Cleaner Production. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.02.043. (forthcoming)

Guenther, T. W. (2013). Conceptualisations of ‘controlling’ in German-speaking countries: analysis and comparison with Anglo-American management control frameworks. Journal of Management Control, 23(4), 269–290.

Gupta, A. K., Smith, K. G., & Shalley, C. E. (2006). The interplay between exploration and exploitation. Academy of Management Journal, 49(4), 693–706.

Güttel, W. H., & Konlechner, S. W. (2009). Continuously hanging by a thread: Managing contextually ambidextrous organizations. Schmalenbach Business Review, 61(2), 150–172.

Güttel, W. H., Konlechner, S. W., Müller, B., Trede, J. K., & Lehrer, M. (2012). Facilitating ambidexterity in replicator organizations: Artifacts in their role as routine-recreators. Schmalenbach Business Review, 64(3), 187–203.

Güttel, W. H., Konlechner, S. W., & Trede, J. K. (2015). Standardized individuality versus individualized standardization: The role of the context in structurally ambidextrous organizations. Review of Managerial Science, 9(2), 261–284.

Haustein, E., Luther, R., & Schuster, P. (2014). Management control systems in innovation companies: A literature based framework. Journal of Management Control, 24(4), 343–382.

Hiebl, M. R. W. (2014). Upper echelons theory in management accounting and control research. Journal of Management Control, 24(3), 223–240.

Hill, S. A., & Birkinshaw, J. (2014). Ambidexterity and survival in corporate venture units. Journal of Management, 40(7), 1899–1931.

Jørgensen, B., & Messner, M. (2009). Management control in new product development: The dynamics of managing flexibility and efficiency. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 21, 99–124.

Kang, S. C., & Snell, S. A. (2009). Intellectual capital architectures and ambidextrous learning: A framework for human resource management. Journal of Management Studies, 46(1), 65–92.

March, J. G. (1991). Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science, 2(1), 71–87.

Malmi, T., & Brown, D. A. (2008). Management control systems as a package: Opportunities, challenges and research directions. Management Accounting Research, 19(4), 287–300.

McCarthy, I. P., & Gordon, B. R. (2011). Achieving contextual ambidexterity in R&D organizations: A management control system approach. R&D Management, 41(3), 240–258.

McNamara, P., & Baden-Fuller, C. (1999). Lessons from the Celltech case: Balancing knowledge exploration and exploitation in organizational renewal. British Journal of Management, 10(4), 291–307.

Medcof, J. T., & Song, L. J. (2013). Exploration, exploitation and human resource management practices in cooperative and entrepreneurial HR configurations. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(15), 2911–2926.

Mundy, J. (2010). Creating dynamic tensions through a balanced use of management control systems. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 35(5), 499–523.

O’Reilly, C. A., & Tushman, M. L. (2013). Organizational ambidexterity. Past, present and future. Academy of Management Perspectives, 27(4), 324–338.

Ouchi, W. G. (1979). A conceptual framework for the design of organizational control mechanisms. Management Science, 25(9), 833–848.

Ouchi, W. G. (1980). Markets, bureaucracies, and clans. Administrative Science Quarterly, 25(1), 129–141.

Raisch, S., & Birkinshaw, J. (2008). Organizational ambidexterity. Antecedents, outcomes, and moderators. Organization Science, 34(3), 375–409.

Raisch, S., Birkinshaw, J., Probst, G., & Tushman, M. L. (2009). Organizational ambidexterity: Balancing exploitation and exploration for a sustained performance. Organization Science, 20(4), 685–695.

Schermann, M., Wiesche, M., & Krcmar, H. (2012). The role of information systems in supporting exploitative and exploratory management control activities. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 24, 31–59.

Selcer, A., & Decker, P. (2012). The structuration of ambidexterity: An urge for caution in organizational design. International Journal of Organizational Innovation, 5(1), 65–96.

Siggelkow, N., & Levinthal, D. A. (2003). Temporarily divide to conquer: Centralized, dezentralized, and reintegrated organizational approaches to exploration and adaptation. Organization Science, 14(6), 650–669.

Simons, R. (1995). Levers of control. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Simons R. (2010). Accountability and control as catalysts for strategic exploration and exploitation: Field study results. Working Paper.

Strauß, E., & Zecher, C. (2013). Management control systems: A review. Journal of Management Control, 23(4), 233–268.

Tessier, S., & Otley, D. (2012). A conceptual development of Simons’ Levers of Control framework. Management Accounting Research, 23(3), 171–185.

Tushman, M. L., & O’Reilly, C. A. (1996). Ambidextrous organizations: Managing evolutionary and revolutionary change. California Management Review, 38(4), 8–30.

Wernerfeldt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171–180.

Winter, S. G., & Szulanski, G. (2001). Replication as strategy. Organization Science, 12(6), 730–743.

Ylinen, M., & Gullkvist, B. (2014). The effects of organic and mechanistic control in exploratory and exploitative innovations. Management Accounting Research, 25(1), 93–112.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Birgit Feldbauer-Durstmüller and two anonymous reviewers for most helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Gschwantner, S., Hiebl, M.R.W. Management control systems and organizational ambidexterity. J Manag Control 27, 371–404 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00187-016-0236-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00187-016-0236-3