Abstract

Most Campylobacter bacteriophages isolated to date have long contractile tails and belong to the family Myoviridae. Based on their morphology, genome size and endonuclease restriction profile, Campylobacter phages were originally divided into three groups. The recent genome sequencing of seven virulent campylophages reveal further details of the relationships between these phages at the genome organization level. This article details the morphological and genomic features among the campylophages, investigates their taxonomic position, and proposes the creation of two new genera, the “Cp220likevirus” and “Cp8unalikevirus” within a proposed subfamily, the “Eucampyvirinae”

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over 200 bacteriophages infecting Campylobacter coli or Campylobacter jejuni have been isolated, the great majority being members of the Myoviridae, although ten have been classified as belonging to the Siphoviridae [1–16]. These phages were isolated with or without enrichment from intestinal contents; human, porcine, and avian fecal matter; sewage; and cultures of lysogenic strains. They are used for typing Campylobacter isolates [17–21] and have been proposed for use in eliminating this bacterium from the intestinal tract of chickens (phage therapy) [22–31] and biocontrol of pathogens on produce and carcasses (aka biocontrol) [1, 32–34].

Unfortunately, the lack of uniform classification criteria and often poor quality of electron micrographs make it very difficult to group them into taxonomic clusters. Morphology, genome size determined by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), and susceptibility to digestion with restriction endonucleases [1–3, 5, 11] have been used to classify some of these viruses into three groups: Group I Campylobacter phages possess genomes of at least 320 kb and heads of 143 nm. Group II phages have isometric capsids of about 99 nm in diameter and genomes of 180-194 kb in size that are resistant to digestion with HhaI endonuclease (GCG↓C). The members of the last group (III) have head sizes of 100 nm and 130-140-kb genomes that are digestible by HhaI [5].

The integration of genome-based information into official taxonomy was proposed for the Myoviridae [35]. In addition, a more recent review of the “T4 superfamily of viruses” defined T4-related bacteriophages as possessing a core genome encoding approximately 37 proteins [36]. This included Campylobacter phages CPt10 and CP220 [37], Delftia phage φW-14 (NC_013697), and Salmonella phage ViI [38]. Adriaenssens and colleagues [39] have recently extended this work by defining a new genus “Viunalikevirus”, which contains six phages related to Salmonella phage ViI. Here, we investigate the taxonomic position of fully sequenced Campylobacter phages and propose the creation of two new genera, the “Cp220likevirus” and “Cp8unalikevirus”, within a proposed subfamily, the “Eucampyvirinae.”

Results

Bacteriophages

We compared seven bacteriophages, belonging to group II (CP220, CPt10, vB_CcoM-IBB_35, CP21) or III (CP81, CPX, NCTC 12673). The phages had been isolated in different places and ecosystems at different times and in different surroundings. Phage vB_CcoM-IBB_35 (also known as phiCcoIBB35) was isolated from the intestines of free-range chickens in Braga, Portugal; CP81 was isolated from the skin of a retail chicken from Bavaria, Germany; CP220 and CPX were also recovered from a retail chicken from the United Kingdom; CPt10 was recovered from slaughterhouse effluent in the United Kingdom; CP21 was isolated from an organic farm in Berlin, Germany. NCTC 12673 was enriched from U.S. poultry excreta. For further details of each phage, the reader is referred to the original publications (see Table 1). In this manuscript, Campylobacter phages will subsequently sometimes be called “campylophages.”

Morphology

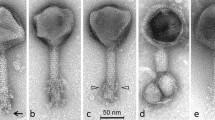

The campylophages have isometric heads and contractile tails and are thus members of the Myoviridae. The morphologies of representative Campylobacter phages are shown in Figs. 1 and 2. Their dimensions are reported in Table 2. The most noticeable difference between the phages of groups II and III is the length of the tail.

Electron micrographs of group II and III Campylobacter phages. Phages were sedimented for 1 h at 25,000 g in a Beckman J2-21 centrifuge using a JA18.1 fixed-angle rotor; washed twice in 0.1 M neutral ammonium acetate under the same conditions; deposited on carbon-coated copper grids; stained with ammonium molybdate (2 %, Mol), uranyl acetate (2 %, UA), or phosphotungstate (2 %, PT); and examined in a Philips EM 300 electron microscope. Bars indicate 100 nm. A–E Type CP220. A Two particles with extended tails assembled end-to-end by entangled tail fibers, Mol. B, C Two aspects of pentagonal heads, UA. D Particle with partially assembled sheath and denuded tail core, PT. E phage with positively stained head and halo around the capsid, UA

F–J Type CP81. F Normal particle with extended tail and tail fibers, Mol. G Two phages with contracted tails adsorbed to small spherical bacterial debris, UA. Note the dark staining of phage heads. H A phage with a contracted tail adsorbed to a piece of bacterial debris, PT. Note the apparent absence of a base plate. I A pentagonal head, PT. J A smaller-than-normal head, an exceedingly rare morphological aberration, UA

Heads are icosahedral, as proven by the observation of both hexagonal and pentagonal capsids. Heads positively stained with uranyl acetate are always shrunken. These phages have necks, but no collars and no apparent base plates. Tail fibers are short and thin. Group II phages (Fig. 1) have longer tails and appear often in pairs held together by entangled tail fibers. Tails are generally extended. Some tails have incomplete sheaths; this represents a hitherto unreported type of morphological aberration. Group III phages (Fig. 2) are unremarkable except that contracted tail tips appear typically adsorbed to spherical vesicles of probable bacterial origin. Preservation of CP220 was difficult as the phage was easily inactivated by rupture of the head and tail contraction.

DNA properties

Cohesive ends could not be detected in either group, while Bal31 analyses suggested that the genomes of these phages are circularly permuted.

While DNA from Campylobacter can be readily isolated, spectrophotometrically quantified, digested with common restriction endonucleases, and amplified using Taq polymerase, the same cannot be said for the genomes of its phages. Proteinase-K-treated DNA from phages NCTC 12673, vB_CcoM-IBB_35, and CP81 partitioned, upon phenol extraction, into the interphase [11, 14]. Commonalities between phages NCTC 12673 (group III) and vB_CcoM-IBB_35 (group II) are that their DNA could not be accurately quantified using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (NanoDrop products, Wilmington, DE), digested with common restriction endonucleases, or amplified with Taq DNA polymerase [13, 14]. A further discrepancy was found between the predicted genome size of these phages based on PFGE and the actual genome size obtained from sequencing [14]. A detailed restriction analysis of CP81 DNA revealed that only enzymes recognizing AT-rich sequences such as DraI (TTT↓AAA), SmiI (ATTT↓AAAT), and VspI (AT↓TAAT) cleaved the DNA efficiently.

The fact that the phage DNA was predominantly found at the phenol-water interface suggested the presence of tightly-bound proteins or a change in the hydrophobicity of the DNA through enzymatic modification. In silico analysis for phage-specific histone-like proteins failed to reveal any likely candidates. Also, amplification of CP81 DNA with QIAGEN REPLI-g (φ29 DNA polymerase) resulted in DNA that could be cleaved with common restriction endonucleases, suggesting that the DNA contains unique modifications [11].

One of the interesting features of group II and III phages is that they have similar capsid dimensions but significantly different genome masses. This could be due to differences in the compaction of the phage genomes.

Genome organization properties

Based on a number of criteria, including mass, mol%G+C, number of genes for tRNAs and homing endonucleases, plus BLASTN homologs, the fully sequenced Campylobacter phages fall into two groups (Table 1). The first group comprises viruses CP220, CPt10, CP21, and vB_CcoM-IBB_35, while the latter contains phages CPX, CP81 and NCTC 12673. Based upon time of submission to GenBank, the two type phages are CP220 and CP81.

We compared the genomes of the phages using progressiveMauve analysis [40]. The results (Supplementary Figure 1AB) confirm the groupings described above and further indicated that there was almost no DNA sequence relatedness between the two groups of phages. While the genomes of CP220, CPt10 and vB_CcoM-IBB_35 are colinear, the genome of CP21 exhibits considerable rearrangement of homologous modules. Group II phages are composed of large modules separated by long DNA repeat regions, which could lead to these rearrangements. The other three phages are circular permutations of one another. This emphasizes the importance of circularly permuted genomes being opened at identical positions so that meaningful comparisons may be made, including the quantitative calculation of the overall DNA sequence identity, using programs such as Stretcher from the EMBOSS suite [41, 42].

At the protein level, similarity was determined using CoreGenes [43, 44] at its default settings (Table 3). Common proteins shared by these two groups of phages include DNA helicase UvsW, RNaseH, topoisomerase (large subunit), putative dUTP pyrophosphatase, poly A polymerase, thymidine kinase, thymidylate synthetase, ribonucleotide reductase (small subunit), co-chaperonin GroES and the following homologs to T4 proteins: gp61 DNA primase subunit, gp44 sliding clamp loader, gp45 sliding clamp, gp62 clamp loader, gp20 portal vertex, gp25 baseplate wedge, gp6 baseplate wedge, gp4 head completion protein, gp23 major capsid, gp18 tail sheath, gp19 tail tube, gp2 DNA end protector, gp5 baseplate hub, gp43 DNA polymerase, gp13 neck, gp41 DNA primase-helicase, gp14 head completion, gp15 tail sheath stabilizer, gp32 ssDNA binding protein, gp3 tail completion, gp21 prohead core scaffold and protease – in other words, the proteins whose genes make up the core genome of T4-like viruses.

Regulatory elements

To investigate the existence of unique regulatory regions within the proposed genera, 100 bp of 5’ upstream sequence data was extracted using extractUpStreamDNA (http://lfz.corefacility.ca/extractUpStreamDNA/) and submitted for MEME analysis at http://meme.sdsc.edu/meme/cgi-bin/meme.cgi [45]. Unlike Escherichia coli and its relatives, whose RpoD (σ70)-dependent promoters conform to the consensus sequence TTGACA(N15-17)TATAAT, these promoters in Campylobacter display no recognizable -35 element and have a modified −10 sequence (TAwAAT) [46]. A/T-rich repeats are found centered at 5-6, 15-17 and 26 bp upstream of the −10 region. In addition, another A/T-rich region is located 7-14 bp downstream of the −10 region. Campylophages displayed multiple copies of a consensus sequence TTAAG(N6)TTAAG(N11)TATAAT, with some evidence for an extended −10 region (TGN) [47], which we believe corresponds to early promoters recognized by the host RNA polymerase (Supplementary Figure 2A). The consensus sequence for late transcription in members of the genus Viunalikevirus [39] is CTAAATAcCcc, while in T4, the late promoter core is TATAAATA [48, 49]. MEME analysis revealed another consensus sequence, CAT(N3)WWWCCTTT (Supplementary Figure 2B). In the case of phage NCTC 12673, this sequence was found upstream of the genes encoding the late transcriptional regulator, major head, tail completion, and portal protein and might therefore function as a late-gene promoter.

tRNAs and codon usage

An analysis of initiation codon usage of nine of the completely sequenced C. jejuni strains using Inidon [50] indicates that AUG is the preferred initiation codon 86.6 % of the time. This is followed by UUG (8.5 %) and GUG (4.7 %). By comparison, campylophage CP220 uses these codons 89.2, 7.2 and 3.6 % of the time. With phage CP81, the predominant codon is AUG (98.3 %), followed by GUG (1.1 %) and ACA (0.5 %). Bacteriophage tRNAs function to enhance translation efficiency, particularly if the cognate codon is poorly represented in the host. The group II and group III phages contain five and two tRNA genes, respectively. The arginyl codon AGA is overrepresented in CP220 and CP81, while the leucyl UUA codon is overrepresented in CP81. Therefore, in these cases, the presence of a phage-encoded tRNA might be advantageous for overall translation efficiency.

Homing endonucleases

All sequenced Campylobacter myoviruses contain homing endonucleases related to Hef [51], which was first found in the T4-like phage U5. This homing endonuclease was located in the ndrA gene of the latter phage, while analogous genes (segH) are similarly located in T4-like coliphages RB15 and RB32. Altogether, we identified 33 homologs unevenly distributed in numbers between the campylophages. These sequences vary considerably in length and may be considered pseudogenes, and they show weak similarity to cd00221, Very Short Patch Repair (Vsr) Endonuclease.

Interestingly, Hef-like sequences are absent in the sequenced Campylobacter genomes. A phylogenetic tree of a subset of Hef-related protein sequences was constructed using “one-click” Phylogeny.fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist at http://phylogeny.lirmm.fr/phylo_cgi/simple_phylogeny.cgi [52]. This suite of programs is based upon MUSCLE alignment [53], Gblocks to eliminate poorly aligned positions and divergent regions [54], and PhyML [55]. Supplementary Figure 3 shows the common subclustering of Hef homologs from phages NCTC 12673, CPX and CP81, suggesting lateral transfer of these elements.

Nature of the large subunit terminase

Using the sequence of the large subunit terminase of Vibrio phage KVP40 (NP_899601) as a TBLASTN probe, two things were immediately apparent: (a) the hits within CPt10, CP220 and vB_CcoM-IBB_35 were contiguous sequences, and (b) those in the other three phages were discontinuous and in opposite orientations, i.e., homology to the N-terminal portion of the protein was found approximately 22 kb away from the region showing homology to the C-terminus. Since these fragments are associated with inteins, this suggests that the complete terminase protein is produced by intein-mediated protein splicing in trans [56–60].

Receptor specificity

Like phages of other bacterial species, campylophages are also specific for their host strains [3, 61]. They have been reported to recognize different structures on the surface of the host cell including capsular polysaccharides (CPS) [61–63] and flagella [61, 64]. The host specificity of a phage is determined by its receptor-binding proteins (RBPs). The genome sequences of at least seven lytic campylophages have been reported; however, gp047, previously annotated as gp48 [14], is the only putative RBP that has so far been characterized in detail. Gp047 was identified as a putative RBP in phage NCTC 12673 and is a large protein (152 kD) that is capable of agglutinating C. jejuni NCTC 11168 cells [14]. Gp047 can also be used to specifically detect C. jejuni cells when immobilized onto microbeads, and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) on gp047-derivatized surfaces allows C. jejuni detection to 102 cfu/ml [65].

Gp047 homologs are present in all seven sequenced campylophages. BLASTN analysis (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) using the gp047 homolog along with the 1000-bp nucleotide sequence downstream of the start codon from phage vB_CcoM-IBB_35 (GenBank ID: AEF56819.1) showed that the genomic region encoding the N-terminal sequence (~300 amino acids) of the putative RBPs and the downstream sequence is conserved only in campylophages belonging to group II. Similarly, BLASTN comparisons of the downstream sequences of the gp047 homologs in group III clustered together and showed >99 % sequence identity. Interestingly, the C-terminal part of gp047 is highly conserved in all the campylophages whose genome sequences have been determined. We designed primers based on the conserved C-terminal homologous region and sequenced the gp047 homologs from other campylophages whose genomes have not yet been sequenced, including NCTC 12678, NCTC 12669 and F336, and the C-terminal region in these three phages is also conserved (Supplementary Figure 4). The open reading frame (ORF) size in the region homologous to gp047 is variable in campylophages (Supplementary Figure 5); most interestingly, phage CPX has three ORFs in the region homologous to gp047. In phage CP81, two ORFs of 669 bp and 1854 bp are at the start of the CP81 annotated genome, while another segment of 1086 bp homologous to the gp047 sequence, encoding the N-terminal region, is located close to the end of the CP81 genome and was not annotated as an ORF. This is most probably because the CP81 genome is circularly permuted and this 1086-bp segment is part of the 669-bp ORF, which results in a single continuous reading frame of 1755 bp. Remarkably, we found a probable single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) at 2305 bp in the gp047 homolog from F336. We sequenced this region seven times and five times found a major peak of deoxythymidine (T) and two times observed a deoxyguanosine (G) nucleoside at this position. Translation of the ORF continues when G is present, but its replacement with T results in a stop codon and a gap of a non-coding region of 693 bp followed the 795-bp-long ORF homologous to the C-terminal region of gp047.

To find out if the host recognition domains of gp047 are localized in the C-terminus, we expressed the recombinant protein in truncated N- (amino acid residues 1-684) and C- (amino acid residues 682-1365) terminal parts and fused each to gold-coated surfaces. The C. jejuni binding domains of gp047 are localized in the conserved C-terminus (Fig. 3). We are currently in the process of expressing the 795-bp ORF of phage F336 in E. coli to check if the host binding domain is also localized in this region. It is exciting to speculate that the F336 phage is evolving to express this smaller ORF independently of the 5’-end 2307-bp ORF or vice versa.

GST-fused gp047, truncated N-(amino acid residues 1-684) and C-terminal parts (amino acid residues 682-1365) were immobilized on gold-coated surfaces and binding of C. jejuni NCTC 11168 was studied as described earlier [65]. The results showed that the host binding domains of gp047 are localized in the C-terminus as the average density of the captured bacteria by full-length gp047 (A) and its N- (B) and C-terminal fragments (C) was 5.47, 0.03 and 5.8 per 100 μ2, respectively

Phylogenetic trees for the major capsid proteins (homologs of T4 gp23; Fig. 4A) and DNA polymerases (homologs of T4 gp43; Fig. 4B) clearly show that there are two distinct groups of phages. Furthermore, it is interesting that for many of the campylophages proteins the closest homologs are to be found not in the phylum Proteobacteria, but among phages of the phylum Cyanobacteria.

Conclusions

The Campylobacter phages described here have icosahedral heads and long contractile tails and thus belong to the family Myoviridae. In the absence of genome sequences, the Campylobacter phages were divided into three groups based on electron microscopic analysis of their head assembly, genome size determined by PFGE, and DNA restriction profiles produced using selected endonucleases [5]. The availability of genome sequences of seven virulent campylophages, which have been published recently, provided further details about the evolution and phylogenetic relationship of these phages. This knowledge can be used for the classification of these viruses. Based on their whole-genome sequence homology and similarity in protein sequences, we suggest grouping these phages into two related genera, exemplified by phages CP220 and CP81. The former, named “Cp220likevirus”, comprises phages CP21, CP220, CPt10, and vB-Ccom-IBB_35. It corresponds to group II phages of campyloviruses. The second, named “Cp8unavirus”, corresponds to group III and comprises phages CP81, CPX, and NCTC 12673. The two genera together constitute the tentative subfamily “Eucampyvirinae” within the family Myoviridae of the order Caudovirales.

This classification is supported by sequence analysis of a putative receptor binding protein (Gp047) and the large subunit terminase, plus phylogenetic analysis of the major capsid protein Gp23, and Gp43-like DNA polymerase. It appears to us to be urgent to sequence Campylobacter phages of group I, which might potentially constitute a third genus within the proposed subfamily. Furthermore, the grouping in and within the proposed subfamily “Eucampyvirinae” is consistent with the recently updated classifications within the families Podoviridae and Myoviridae [35, 66].

References

Atterbury RJ, Connerton PL, Dodd CE, Rees CE, Connerton IF (2003) Isolation and characterization of Campylobacter bacteriophages from retail poultry. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:4511–4518

Connerton PL, Loc Carrillo CM, Swift C, Dillon E, Scott A, Rees CE, Dodd CE, Frost J, Connerton IF (2004) Longitudinal study of Campylobacter jejuni bacteriophages and their hosts from broiler chickens. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:3877–3883

Hansen VM, Rosenquist H, Baggesen DL, Brown S, Christensen BB (2007) Characterization of Campylobacter phages including analysis of host range by selected Campylobacter Penner serotypes. BMC Microbiol 7:90

Fletcher RD (1965) Activity and morphology of Vibrio coli phage. Am J Vet Res 26:361–364

Sails AD, Wareing DR, Bolton FJ, Fox AJ, Curry A (1998) Characterisation of 16 Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli typing bacteriophages. J Med Microbiol 47:123–128

Bryner JH, Ritchie AE, Booth GD, Foley JW (1973) Lytic activity of vibrio phages on strains of Vibrio fetus isolated from man and animals. Appl Microbiol 26:404–409

Bryner JH, Ritchie AE, Foley JW, Berman DT (1970) Isolation and characterization of a bacteriophage for Vibrio fetus. J Virol 6:94–99

Loc Carrillo CM, Connerton PL, Pearson T, Connerton IF (2007) Free-range layer chickens as a source of Campylobacter bacteriophage. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 92:275–284

el-Shibiny A, Connerton PL, Connerton IF (2005) Enumeration and diversity of campylobacters and bacteriophages isolated during the rearing cycles of free-range and organic chickens. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:1259–1266

el-Shibiny A, Scott A, Timms A, Metawea Y, Connerton P, Connerton I (2009) Application of a group II Campylobacter bacteriophage to reduce strains of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli colonizing broiler chickens. J Food Prot 72:733–740

Hammerl JA, Jackel C, Reetz J, Beck S, Alter T, Lurz R, Barretto C, Brüssow H, Hertwig S (2011) Campylobacter jejuni group III phage CP81 contains many T4-like genes without belonging to the T4-type phage group: implications for the evolution of T4 phages. J Virol 85:8597–8605

Hammerl JA, Jackel C, Reetz J, Hertwig S (2012) The complete genome sequence of bacteriophage CP21 reveals modular shuffling in Campylobacter group II phages. J Virol 86:8896

Carvalho CM, Kropinski AM, Lingohr EJ, Santos SB, King J, Azeredo J (2012) The genome and proteome of a Campylobacter coli bacteriophage vB_CcoM-IBB_35 reveal unusual features. Virol J 9:35

Kropinski AM, Arutyunov D, Foss M, Cunningham A, Ding W, Singh A, Pavlov AR, Henry M, Evoy S, Kelly J, Szymanski CM (2011) Genome and proteome of Campylobacter jejuni bacteriophage NCTC 12673. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:8265–8271

Owens J, Barton MD, Heuzenroeder MW (2012) The isolation and characterization of Campylobacter jejuni bacteriophages from free range and indoor poultry. Vet Microbiol 162:144–150

Hwang S, Yun J, Kim KP, Heu S, Lee S, Ryu S (2009) Isolation and characterization of bacteriophages specific for Campylobacter jejuni. Microbiol Immunol 53:559–566

Frost JA, Kramer JM, Gillanders SA (1999) Phage typing of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli and its use as an adjunct to serotyping. Epidemiol Infect 123:47–55

Grajewski BA, Kusek JW, Gelfand HM (1985) Development of a bacteriophage typing system for Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. J Clin Microbiol 22:13–18

Khakhria R, Lior H (1992) Extended phage-typing scheme for Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. Epidemiol Infect 108:403–414

Bryner JH, Ritchie AE, Foley JW (1982) Techniques for phage typing Campylobacter jejuni. In: Newell DG (ed) Campylobacter: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and biochemistry. MTP Press, Lancaster, pp 52–55

Salama SM, Bolton FJ, Hutchinson DN (1990) Application of a new phagetyping scheme to campylobacters isolated during outbreaks. Epidemiol Infect 104:405–411

Carvalho CM, Gannon BW, Halfhide DE, Santos SB, Hayes CM, Roe JM, Azeredo J (2010) The in vivo efficacy of two administration routes of a phage cocktail to reduce numbers of Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni in chickens. BMC Microbiol 10:232

Lin J (2009) Novel approaches for Campylobacter control in poultry. Foodborne Pathog Dis 6:755–765

Connerton PL, Timms AR, Connerton IF (2011) Campylobacter bacteriophages and bacteriophage therapy. J Appl Microbiol 111:255–265

Havelaar AH, Mangen MJ, de Koeijer AA, Bogaardt MJ, Evers EG, Jacobs-Reitsma WF, van PW, Wagenaar JA, de Wit GA, van der Zee H, Nauta MJ (2007) Effectiveness and efficiency of controlling Campylobacter on broiler chicken meat. Risk Anal 27:831–844

Carvalho CM, Gannon BW, Halfhide DE, Santos SB, Hayes CM, Roe JM, Azeredo J (2010) The in vivo efficacy of two administration routes of a phage cocktail to reduce numbers of Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni in chickens. BMC Microbiol 10:232

Carvalho CAOCM (2010) Use of bacteriophages to control Campylobacter in poultry. PhD thesis. Escola de Engenharia, Univeridade de Minho, Braga

Carvalho CM, Santos SB, Kropinski AM, Ferreira EC, Azeredo J (2012) Phages as therapeutic tools to control major foodborne pathogens: Campylobacter and Salmonella. In: Kurtboke I (ed) Bacteriophages. InTech, Rijeka, pp 179–214

Loc Carrillo C, Atterbury RJ, el-Shibiny A, Connerton PL, Dillon E, Scott A, Connerton IF (2005) Bacteriophage therapy to reduce Campylobacter jejuni colonization of broiler chickens. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:6554–6563

Wagenaar JA, Van Bergen MA, Mueller MA, Wassenaar TM, Carlton RM, Wagenaar JA, Van Bergen MAP, Mueller MA, Wassenaar TM, Carlton RM (2005) Phage therapy reduces Campylobacter jejuni colonization in broilers. Vet Microbiol 109:275–283

Wagenaar JA, Mevius DJ, Havelaar AH (2006) Campylobacter in primary animal production and control strategies to reduce the burden of human campylobacteriosis. Revue Scientifique et Technique 25:581–594

Orquera S, Golz G, Hertwig S, Hammerl J, Sparborth D, Joldic A, Alter T (2012) Control of Campylobacter spp. and Yersinia enterocolitica by virulent bacteriophages. J Mol Genet Med 6:273–278

Goode D, Allen VM, Barrow PA (2003) Reduction of experimental Salmonella and Campylobacter contamination of chicken skin by application of lytic bacteriophages. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:5032–5036

Atterbury RJ, Connerton PL, Dodd CE, Rees CE, Connerton IF (2003) Application of host-specific bacteriophages to the surface of chicken skin leads to a reduction in recovery of Campylobacter jejuni. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:6302–6306

Lavigne R, Darius P, Summer EJ, Seto D, Mahadevan P, Nilsson AS, Ackermann H-W, Kropinski AM (2009) Classification of Myoviridae bacteriophages using protein sequence similarity. BMC Microbiol 9:224

Petrov VM, Ratnayaka S, Nolan JM, Miller ES, Karam JD (2010) Genomes of the T4-related bacteriophages as windows on microbial genome evolution. Virol J 7:292

Timms AR, Cambray-Young J, Scott AE, Petty NK, Connerton PL, Clarke L, Seeger K, Quail M, Cummings N, Maskell DJ, Thomson NR, Connerton IF (2010) Evidence for a lineage of virulent bacteriophages that target Campylobacter. BMC Genomics 11:214

Pickard D, Toribio AL, Petty NK, van TA, Yu L, Goulding D, Barrell B, Rance R, Harris D, Wetter M, Wain J, Choudhary J, Thomson N, Dougan G (2010) A conserved acetyl esterase domain targets diverse bacteriophages to the Vi capsular receptor of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi. J Bacteriol 192:5746–5754

Adriaenssens EM, Ackermann HW, Anany H, Blasdel B, Connerton IF, Goulding D, Griffiths MW, Hooton SP, Kutter EM, Kropinski AM, Lee JH, Maes M, Pickard D, Ryu S, Sepehrizadeh Z, Shahrbabak SS, Toribio AL, Lavigne R (2012) A suggested new bacteriophage genus: “Viunalikevirus”. Arch Virol 157:2035–2046

Darling AE, Mau B, Perna NT (2010) progressiveMauve: multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS ONE 5:e11147

Ceyssens PJ, Glonti T, Kropinski NM, Lavigne R, Chanishvili N, Kulakov L, Lashkhi N, Tediashvili M, Merabishvili M (2011) Phenotypic and genotypic variations within a single bacteriophage species. Virol J 8:134

Olson SA, Olson SA (2002) EMBOSS opens up sequence analysis. European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Briefings Bioinf 3:87–91

Zafar N, Mazumder R, Seto D (2002) CoreGenes: a computational tool for identifying and cataloging “core” genes in a set of small genomes. BMC Bioinf 3:12

Kropinski AM, Borodovsky M, Carver TJ, Cerdeno-Tarraga AM, Darling A, Lomsadze A, Mahadevan P, Stothard P, Seto D, Van DG, Wishart DS (2009) In silico identification of genes in bacteriophage DNA. Methods Mol Biol 502:57–89

Bailey TL, Elkan C (1995) The value of prior knowledge in discovering motifs with MEME. ISMB 3:21–29

Wösten MM, Boeve M, Koot MG, van Nuenen AC, van der Zeijst BA (1998) Identification of Campylobacter jejuni promoter sequences. J Bacteriol 180:594–599

Mitchell JE, Zheng D, Busby SJ, Minchin SD (2003) Identification and analysis of ‘extended-10’ promoters in Escherichia coli. Nucl Acids Res 31:4689–4695

Nechaev S, Geiduschek EP (2008) Dissection of the bacteriophage T4 late promoter complex. J Mol Biol 379:402–413

Geiduschek EP, Kassavetis GA (2010) Transcription of the T4 late genes. Virol J 7:288

Villegas A, Kropinski AM (2008) An analysis of initiation codon utilization in the domain bacteria—concerns about the quality of bacterial genome annotation. Microbiology 154:2559–2661

Sandegren L, Nord D, Sjoberg BM (2005) SegH and Hef: two novel homing endonucleases whose genes replace the mobC and mobE genes in several T4-related phages. Nucl Acids Res 33:6203–6213

Dereeper A, Guignon V, Blanc G, Audic S, Buffet S, Chevenet F, Dufayard JF, Guindon S, Lefort V, Lescot M, Claverie JM, Gascuel O (2008) Phylogeny.fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucl Acids Res 36:W465–W469

Edgar RC (2004) MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinf 5:113

Castresana J (2000) Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol 17:540–552

Guindon S, Gascuel O (2003) A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol 52:696–704

Saleh L, Perler FB (2006) Protein splicing in cis and in trans. Chem Rec 6:183–193

Kropinski AM, Arutyunov D, Foss M, Cunningham A, Ding W, Singh A, Pavlov AR, Henry M, Evoy S, Kelly J, Szymanski CM (2011) Genome and proteome of Campylobacter jejuni bacteriophage NCTC 12673. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:8265–8271

Elleuche S, Poggeler S (2010) Inteins, valuable genetic elements in molecular biology and biotechnology. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 87:479–489

Dassa B, Amitai G, Caspi J, Schueler-Furman O, Pietrokovski S (2007) Trans protein splicing of cyanobacterial split inteins in endogenous and exogenous combinations. Biochemistry 46:322–330

Buchinger E, Aachmann FL, Aranko AS, Valla S, Skjak-Braek G, Iwai H, Wimmer R (2010) Use of protein trans-splicing to produce active and segmentally (2)H, (15)N labeled mannuronan C5-epimerase AlgE4. Protein Sci 19:1534–1543

Coward C, Grant AJ, Swift C, Philp J, Towler R, Heydarian M, Frost JA, Maskell DJ (2006) Phase-variable surface structures are required for infection of Campylobacter jejuni by bacteriophages. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:4638–4647

Sorensen MC, van Alphen LB, Harboe A, Li J, Christensen BB, Szymanski CM, Brondsted L (2011) Bacteriophage F336 recognizes the capsular phosphoramidate modification of Campylobacter jejuni NCTC11168. J Bacteriol 193:6742–6749

Holst Sørensen MC, van Alphen LB, Fodor C, Crowley SM, Christensen BB, Szymanski CM, Brøndsted L (2012) Phase variable expression of capsular polysaccharide modifications allows Campylobacter jejuni to avoid bacteriophage infection in chickens. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2:11

Zhilenkov EL, Popova VM, Popov DV, Zavalsky LY, Svetoch EA, Stern NJ, Seal BS (2006) The ability of flagellum-specific Proteus vulgaris bacteriophage PV22 to interact with Campylobacter jejuni flagella in culture. Virol J 3:50

Singh A, Arutyunov D, McDermott MT, Szymanski CM, Evoy S (2011) Specific detection of Campylobacter jejuni using the bacteriophage NCTC 12673 receptor binding protein as a probe. Analyst 136:4780–4786

Lavigne R, Seto D, Mahadevan P, Ackermann H-W, Kropinski AM (2008) Unifying classical and molecular taxonomic classification: analysis of the Podoviridae using BLASTP-based tools. Res Microbiol 159:406–414

Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE (2004) WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res 14:1188–1190

Carvalho C, Susano M, Fernandes E, Santos S, Gannon B, Nicolau A, Gibbs P, Teixeira P, Azeredo J (2010) Method for bacteriophage isolation against target Campylobacter strains. Lett Appl Microbiol 50:192–197

Kropinski AM, Van den Bossche A, Lavigne R, Noben JP, Babinger P, Schmitt R (2012) Genome and proteome analysis of 7-7-1, a flagellotropic phage infecting Agrobacterium sp H13-3. Virol J 9:102

Acknowledgments

AMK would like to thank Andre Villegas for developing “extractUpStreamDNA”. The authors are thankful to Denis Arutyunov and Jessica Sacher for helpful discussions and help with phage preparations, and to Cheryl Nargang for her help with nucleotide sequencing and analysis of gp047 homolog from phage F336. The bacteriophage receptor-binding protein studies were funded by an Alberta Innovates Scholar Award (CMS) and a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Strategic Grant (CMS). RL and AMK are chair and vice chair, respectively, of the prokaryotic virus subcommittee of the ICTV (International Committee for Taxonomy of Viruses).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

705_2013_1788_MOESM3_ESM.tif

WebLogo [67] of putative early promoters of Campylobacter phage CP81 (TIFF 1567 kb)

705_2013_1788_MOESM5_ESM.tif

Phylogenetic analysis of Hef-like proteins from the phages of this study. Created using phylogeny.fr in “one click” mode [52] (TIFF 2381 kb)

705_2013_1788_MOESM6_ESM.tif

Multiple sequence alignment of Gp047 C-terminal (gp48-CT) homologs from different campylophages showing high levels of homology among the last 489 amino acids (TIFF 3245 kb)

705_2013_1788_MOESM7_ESM.tif

Variation in ORF size in the gp047 homologs in campylophages. DNA sequences encoding for the C-terminal, conserved part of Gp047 was amplified by PCR and the nucleotide sequence was determined in campylophages NCTC12669, NCTC12678 and F336 using primers CS828 (5’ GCAGACAATGTAGCATATAATATTAGTAATACTCCATTAGTACCT 3’) and CS827 (5’ TACATAATACCATATAGCTTTTACATCAGAAACAGA 3’). Nucleotide sequences flanking the conserved region were determined by primer walking. Genomic DNA was pre-amplified using DNA polymerase φ29 and random primers as described earlier [14]. The pre-amplified DNA was treated with SI nuclease (Thermo Scientific) to remove any hyperbranched secondary structures; SI-nuclease-treated DNA was purified by the phenol/choloroform extraction method followed by ethanol precipitation. Regions of interest were then amplified by PCR using Phusion Hot Start II High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (Thermo Scientific) and PCR products were cleaned by treating with exonuclease I (USB Corporation) to remove the primers, followed by treatment with shrimp alkaline phosphatase (USB) to dephosphorylate the nucleotides. Nucleotide sequencing was done using BigDye Terminator v3.1 at the Molecular Biology Services Unit, University of Alberta. *not annotated as an ORF in the published genome (TIFF 390 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Javed, M.A., Ackermann, HW., Azeredo, J. et al. A suggested classification for two groups of Campylobacter myoviruses. Arch Virol 159, 181–190 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-013-1788-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-013-1788-2