Abstract

Over 60% of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients achieve a good response after 12 months of treatment when following the European league against rheumatism (EULAR) guidelines for treatment. However, almost half of patients still suffer from moderate to severe disease activity despite this. In addition, mental health problems may remain despite reduced measures of inflammation systemically and within joints. Depression is two times more common in RA patients than in the general population, and intriguingly a bi-directional relationship with RA has been shown in cross-sectional studies. Chronic inflammation impairs the physiological responses to stress including effective coping behaviours, resulting in depression, which leads to a worse long-term outcome in RA. In RA patients, the pain score is not always solely related to inflammatory arthritis and immunological disease activity by Bąk et al. (Patient Prefer Adherence 13:223–231, [1]). Non-inflammatory pain secondary to anxiety, depression, sleep disturbance and the psychosocial situation needs to be considered whilst fibromyalgia, mechanical pain and neuropathic pain can also contribute to overall pain scores by Chancay et al. (Women's Midlife Health 5:3, [2]). Hence, the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline for the management of RA included psychological interventions for fatigue, low mood and social well-being (NICE NG100, 2018) [3], and the NICE clinical guidelines (CG91) [4] suggest managing mental health and depression in chronic medical conditions to improve treatment outcomes. This is a narrative review of the impact of mental health on RA disease activity in terms of patient-reported outcomes (PROs).

Plain Language Summary

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune inflammatory condition that affects 1% of the global population. RA can cause inflammation and damage to the joints. It can also present with extra-articular manifestations, affecting other major organs in the body. RA patients are more prone to have anxiety, depression and cognitive impairment compared to the general healthy population. Those mental health conditions contribute to less responsiveness to treatment and higher disease activity in RA mainly due to fatigue and bodily pain. Medications used in RA can improve anxiety and depression to a certain extent but not completely. Therefore, it is important to determine the most appropriate tool to monitor mental health well-being and quality of life (QoL) of RA patients in rheumatology outpatient clinics to optimise the care of the RA patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) affects 1% of adults. |

Up to 17% of RA patients have a major depressive disorder. |

Despite a “treat-to-target” approach, many RA patients continue to suffer considerable symptoms, and depression is an important factor in treatment refractory cases. |

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs can have positive effects on depressive symptoms but are often not completely effective. |

More research studies are needed to determine the best tools for assessment of depression/anxiety and the most effective strategies for treating mental health problems in RA patients. |

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic systemic autoimmune condition that mainly affects synovial joints causing inflammation (synovitis), joint erosion and cartilage damage. This results in reduced functional status and disability in many patients. RA can also manifest as extra-articular disease, which can affect most organs of the body, leading to higher mortality and morbidity rates [5]. Cardiovascular manifestations such as pericarditis, myocarditis, pericardial and pleural effusions, and congestive cardiac failure, skin, ophthalmology, gastrointestinal, nervous and renal system dysfunction can occur in the long term in RA patients [6].

The prevalence of RA is 1% in most countries, the incidence being reported as 40/100,000 for those fulfilling the 2010 American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/EULAR classification criteria at baseline [7]. Despite tight disease management according to the “treat-to-target” (T2T) approach [8], some RA patients still have high disease activity [9]. The disease activity score using 28 joints (DAS28) is commonly used to monitor a patients’ response based on the tender joint count (TJC), swollen joint count (SJC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and patient visual analogue score (VAS). The main disadvantage, or advantage, of the DAS28 score is the subjectivity of some components, with the patients’ VAS and TJC as the parameters of the scoring system [8]. These subjective measures can be influenced by low mood and depression in RA patients [2]. In RA, quality of life (QoL) is significantly decreased because of pain, fatigue and disability, causing mood change in the form of anxiety and depression [11, 12]. Observational studies have described a high prevalence of depression and anxiety in RA [13]; major depressive disorders (MDDs) are detected in 17% of RA patients, and local and systemic inflammation plays an important role in anxiety and depression [14]. Depression, according to the World Health Organisation Global Burden of Disease Study, is the most pressing issue in the middle-aged population [15]. There are ongoing studies looking at the impact of depression on disease activity in RA and vice versa. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Contributing Factors for Depression in RA

Depression and anxiety are major psychiatric problems that can be related to RA either because of a biological and cytokine-related mechanism or because of the psychological impact of chronic medical adversity on a patients’ mental well-being [16]. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) such as baseline bodily pain, fatigue and early morning stiffness (EMS) predominantly affect QoL in RA patients [17], contribute to high disease activity and are also likely to increase depression [18]. Psychological stress can interfere with the immune system, and it is also evident that chronic inflammatory conditions can have an impact on the central nervous system [19].

Pain and Fatigue in RA

Pain in RA can be unrelated to joint damage and even occur before the onset of local inflammation and swelling in the synovium [11]. RA patients with a higher degree of pain reported a higher reduction in QoL [18], and a significant relationship between DAS28 score and QoL has been observed [1, 20].

According to the “Invisible Disease: Rheumatoid Arthritis and Chronic Fatigue Survey” by the UK patient-led charity the National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society (NRAS) in 2014, fatigue is very common in RA, and 90% of RA patients reported fatigue as the main factor causing low mood and depression, 89% experiencing chronic fatigue and 79% never being assessed for their level of fatigue [21]. Overwhelming fatigue can cause significant mood change [5], and it is negatively and significantly related to self-efficacy, physical function, swelling, early morning stiffness (EMS) and increased levels of ESR or lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated interleukin-6 (IL-6). The relationship between fatigue and anxiety could be biased by disease duration, patients’ general health and comorbidities [22].

The Patients’ View

RA patients report the effect of the disease on their mental well-being and frequently describe tearfulness, irritability, frustration, anxiety and depression [17]. Patients and physicians report anxiety and depression differently. One thousand fifteen pairs of RA patients and their physicians completed the anxiety/depression questionnaires; 38.4%, 9.9% and 67.1% cases of anxiety/depression were reported by the patients only, physicians only and both patients and physicians respectively [23].

Mental Health Disorders and RA

Depression negatively affects RA patients’ ability to function in the presence of their physical symptoms, such as pain and fatigue [20]. Long-term exposure to raised cytokines such as IL-1β, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α and IL-6 in RA can cause maladaptive responses to sickness behaviour, causing fatigue, pain, fever, anhedonia and depression [24]. Depression presents with low mood, low self-esteem, fatigue, lethargy, insomnia, psycho-motor dysfunction and repetitive negative thoughts [25]. MDD presents with more aggressive symptoms of depression together with feelings of low self-worth, difficulty concentrating, anhedonia and suicidal ideation, making it potentially fatal if left untreated [25].

RA and Depression

Depression is two times more common in RA than in the general population and constitutes the most common mental health disorder associated with RA [16, 26]. A meta-analysis showed that the prevalence of depression in RA ranges between 14 and 48% while major depressive disorders occur in 16.8% of RA patients [26]; 33% of RA patients left their jobs and 16% changed jobs within the first 2 years of diagnosis [20]. The overlap of some depressive symptoms in RA (lack of sleep, fatigue and poor appetite) and the variety of screening methods used to detect depression may contribute to the variation in prevalence of depression described in the RA population [26].

The complex bidirectional relationship between RA and depression has been studied extensively [27] but it is yet to be fully elucidated. Inflammatory arthritis constitutes a risk factor for developing mental health disorders, further supporting the inflammatory mechanism underlying depression in RA [16]. Chronic inflammation impairs the physiological response to stress including effective coping behaviours [16]. Thereby, stress constitutes an aggravating factor in RA that may lead to depression [28]. Depression also seems to reduce adherence to medical treatment [29]. This could be explained by hopelessness and negative cognitive perception of one’s health and belief in the ability to function in the presence of RA [16, 20]. In addition, RA patients with depression have impaired coping responses to pain, fatigue and disability, leading to reduced physical exercises and engagement in social interaction [16, 30]. Subsequently, the decline in physical health and function increases emotional distress, frustration and eventually depression [16, 31]. These changes contribute to poor outcomes, making it important to tackle depression to improve RA outcomes and/or to reduce factors that undermine effectiveness of RA treatment [31].

Effects of Mood, Pain and Fatigue on Traditional Measures of RA Disease Activity

In the management of RA, a multifactorial approach is used to judge remission. These include DAS28 remission (< 2.6), structural remission on radiology imaging, immunological remission, low co-morbidity index, medication remission and patient defined remission [32]. DAS28-ESR, recommended by EULAR for RA disease activity measurement, showed a composite reliability of 0.86 [33]; however, the subjective parameters of the scoring system make it less reliable [34]. The other scoring systems for assessing RA disease activity include the clinical disease activity index (CDAI) and simplified disease activity index (SDAI). Specificity and sensitivity for CDAI (P value < 0.001; 95% confidence interval (CI) 94.2–98.1) showed 85.3% and 97% respectively and those for SDAI (P value < 0.001; 95% CI 87.5–94.18) showed 62.2% and 97.6% [35]. RA patients diagnosed with depression have reduced rates of clinically significant RA remission, increased pain, worse function and quality of life and increased mortality [26, 36]. PROs hence become an essential factor for optimising the holistic care of RA.

Assessment Tools for Mental Health in RA Patients

In the management of chronic medical diseases such as RA, shared decision-making and patient-centred care are regarded as the optimal approach [11]. Hence, the UK NICE guideline (NG100, 2018) included psychological intervention for fatigue, low mood and social well-being in the management of RA [3], and the NICE clinical guideline (CG91) suggested managing mental health and depression to improve RA treatment outcome [4]. Anxiety and depression are the most common mental health conditions in RA [13]. The OMERACT (Outcome Measures in Rheumatology) international network has been researching on the standardisation of outcome measures in RA [37]. However, to choose the standard measurement tool to assess mental health and PROs and to include patients’ mood in RA annual review are still challenging for the clinicians [11].

The British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register (BSRBR) measured depression in bDMARDs-treated RA patients, using the Short Form 36 (SF-36) Normal Mental Health (nMH) subset and EuroQoL five-dimension scale (EQ5D) [31]. A high detection rate of depression on SF-36 illustrated a high sensitivity (92.6%) of the measurement but a low specificity (73.2%). EQ5D has shown moderate sensitivity and specificity in detecting current depression [31]. The Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS) is used to measure the level of anxiety [Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (α) = 0.87], depression (α = 0.94) and stress (α = 0.91) in RA patients. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is considered another reliable tool that measures anxiety (α = 0.89) and depression (α = 0.86) in the RA population [13], and depression [HADS (mean ± SD) 12.4 ± 5.39] was detected in 66% of RA patients [20]. The Beck Depression Inventory Scale II (BDI-II) with high sensitivity and specificity (72.7% & 78.4% respectively) was used in a cross-sectional study to measure the severity of depression in RA patients, and it was found that the cut-off point on the BDI-II scale for depression should be higher in patients with chronic pain [38, 39]. Another cross-sectional study, the VADERA II study, showed at least mild depression on the BDI-II scale in 27.7% (95% CI 24.91–30.63) of RA patients [40]. The severity of depression was measured by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) in a retrospective study [41]. A systematic review of 33 articles drew the conclusion that SF-36 is an initial valid method to assess health-related (HR) QoL and mental status in RA patients [42]. To further detect depression or anxiety, other screening methods seem to be valid and easy to complete, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) and HADS [26].

Assessment Tools for PROs

Patient global assessment (PGA), due to its simplicity and feasibility, is the second most used single-item tool in RA that broadly reflects a patient’s experience of disease [31, 43]. The reliability, sensitivity to pain and global health, and construct validity for the numerical rating scale (NRS), verbal rating scale (VRS) and VAS have been verified [43]. Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) can assess the level of fatigue and quality of sleep [44]. The Bristol Rheumatoid Arthritis Fatigue Multidimensional Questionnaire (BRAF-MDQ) (α = 0.75–0.96) and BRAF Numerical Rating Scales (BRAF-NRS) are also used to measure the level of fatigue and coping [45]. The severity of fatigue was measured using the Checklist Individual Strength (CIS)-fatigue score (range 0–56) in 230 RA patients in a cross-sectional study. The result showed 44% of patients have severe fatigue (CIS ≥ 35), and it has a bidirectional relationship with reduced physical activity. CIS score (mean ± SD) 32.1 ± 12.6 of RA patients lies between the healthy control group and patients with chronic fatigue syndrome [46].

The Functional Assessment Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F) scale and SF-36 were the measurements used most often in clinical trials to measure PROs and fatigue [47]. PGA is a valid tool to measure PROs, NRS and VAS showing better concurrent reliability than VRS [48]. HAQ-DI and BRAF-NRS are also considered reliable assessment tools for fatigue in RA [45].

Mechanisms of Depression in RA: Effects of Inflammatory Cytokines on the Brain

The pathophysiology of RA is multifactorial. The proinflammatory effects of TNF-α [49] on the function of other cytokines including IL-1, IL-6, IL-8 and GM-CSF are of central importance in the pathogenesis of RA. The circadian rhythm of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α) and glucocorticoids explains a worse disease activity of RA in the early morning [50]. T cell differentiation and T helper (Th) cells, CD4 + cell differentiation, formation of Th1 cells and secretion of IFN-γ [51] stimulated by IL-12 are responsible for T-cell-related RA flares. IL-23 together with IL-17A, IL-1 and IL-6 induces systemic and local inflammation in RA [52, 49]. The correlation among fatigue, depression and the mechanism of cytokines in autoimmune diseases was shown in cross-sectional trials [5].

There are many hypotheses regarding how peripheral cytokines, local inflammation and swelling induce the inflammation of extra-articular tissue and cerebral inflammation. A significantly higher level of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α in RA predisposes to extensive atherogenesis [54]. IL-1 and IFN-alpha enhance the release of tryptophan metabolites and oxidative stress, causing delayed neurogenesis and fatigue [56]. Peripheral inflammation and cytokines IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-α transmit signals to the brain via either primary afferent neurons [57] or the endothelial cells of cerebral vessels where IL-1 acts on macrophage-like cells in the CNS, disturbing neural integrity where the blood brain barrier becomes less intact [11, 25]. Chronic inflammation can interfere with glutamate neurotransmitters causing neurocircuitry malfunction at the glia [58]. Neuroinflammation and microglial activation associated with systemic inflammation were seen on PET imaging in the cases of systemic inflammation in a small preliminary study [59].

Fatigue and Cytokines

IL-6 activates the HPA axis without a compensated production of cortisol, resulting in fatigue [60]. The aetiology of fatigue in RA has been widely explained by the effect of cytokines [61, 62] IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6 and TNF-α on the function of noradrenaline, dopamine and serotonin through monoamine transporters in neurons. The effect of dopamine and serotonin on the mesolimbic pathway responsible for anhedonia can cause “motivational fatigue” whilst abnormal dopamine action on the nigrostriatal pathway is associated with “physical fatigue”, and noradrenergic-dopaminergic action on the mesocortical pathway interferes with concentration and short-term memory causing “cognitive fatigue” [24].

Depression and Cytokines

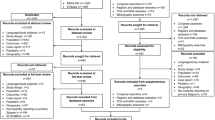

Advances in “immunopsychiatry” have established a better understanding of the relationship between depression and inflammation, and over the last 2 or 3 decades, some have considered depression an inflammation-related disorder (Fig. 1) [63]. Increasing levels of IL-1, IL-6, C-reactive protein and TNF-alpha in T-cell-mediated inflammation were found in patients with depression or anxiety [64]. HPA axis dysregulation by IL-6 may lead to anxiety and depression in RA patients [60]. The level of IL-17A has also been shown to be highly associated with the severity of depression [65]. CRP is a strong indicator of disease activity in RA [54], and a high level of CRP induces anhedonia by inhibiting the function of the ventromedial cortex of the brain [66]. In children with inflammatory medical conditions, the risk of depression in adulthood may be high because of permanent effects as a result of early exposure to stress, high levels of CRP, and raised leucocyte count and IL-6 [67]. An increased level of IL-6 in CSF is associated with a decrease in serotonin metabolites, which contributes to depression, but no relationship between IL-6 and catecholamines has been found [68]. A raised IL-6 level for ≥ 6 months plays an important role in the occurrence of depression [66], and more suicide attempts are seen in people with an increased CSF IL-6 level [67]. In RA, inflammatory markers including CRP, ESR and pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1, Il-6 and IFN-α levels are elevated, and such increased levels of inflammation are regarded as a “biological scar” that increases the risk of depression [69].

Adapted from “Impact of Inflammation on the Brain and Behaviour” [63] with the respective assessment tools

Cognitive Function and Cytokines

Cognitive impairment may occur in RA patients because of the direct effect of inflammation on the brain, the impact on cerebral blood vessels in the same way as cardiovascular complications or adverse effects from glucocorticoids and immunosuppressants [70]. Pain, fatigue, anxiety and depression are also responsible for cognitive dysfunction. Cytokines released in RA cause systemic inflammation and can interfere with mood, cognition and sleep [27]. Bartolini et al. reported in their cohort study that 38–70% of RA patients have cognitive impairment [71]. A study performed by Shin et al. used the American College of Rheumatology neuropsychological battery modified for RA to assess cognitive function scores in 144 RA patients, and the results showed cognitive impairment in executive function, visuo-spatial learning and verbal memory as > 20%, 29% and 18% respectively [72]. A cross-sectional study assessed cognitive function using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA) on 60 female RA patients taking MTX or bDMARDs, and the results showed > 60% RA patients scored MOCA < 26 (normal ≥ 26) compared to 49% in the control group [73]. Another study that measured the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score, level of depression, VAS and DAS28 reported the correlation between a low level of MMSE and VAS but not between depression and cumulative steroid dose [74].

RA Therapies: Impacts on Fatigue, Depression and Cognition

RA is treated with conventional synthetic (cs) disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), biologic (b) DMARDs, targeted synthetic (ts) DMARDs and glucocorticoids [8]. An open-label cohort study found that bDMARDs improve depression in RA patients [75]. Another prospective single-blinded study reported that csDMARDs and bDMARDs have a similar effect on improving depressive symptoms in RA patients [76].

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

A systematic review of 30 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) showed that NSAIDs alleviated symptoms of depression [standard mean difference (SMD) − 0.55, 95% CI − 0.75 to − 0.35] compared to the placebo arm [77]. A negative association between long-term NSAID use and depression [HR (95% CI): 0.20 (0.04–0.87)] but a non-specific statistical correlation on repeated testing is seen [78]. Celecoxib, the selective COX-2 inhibitor, showed evidence of improving anhedonia and symptoms of depression in a rodent model (P > 0.05 compared to fluoxetine) [79]. Aspirin and N-acetylcysteine combination therapy improved symptoms of bipolar disorder in 67% of patients [80].

Glucocorticoids

The glucocorticoid receptor is important in maintaining the function of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which is responsible for the occurrence of depression. An experimental study showed that prednisolone acetate 40 mg/kg can induce depression-like behaviour in rhesus macaques [81]. Exogenous corticosterone can cause induction of glutamate at synapses, which contributes to mood disorders [82, 83]. Cognitive decline is found to be related to current or long-term steroid use (even low dose) in RA patients as a vascular side effect [72] but another study reported no significant relation between MMSE and chronic glucocorticoid use [74].

csDMARDs

The health-related QoL (HRQoL) is significantly low in RA patients compared to the general population; pain and fatigue are the main contributing factors [1]. The effect of csDMARDs on QoL, functional status, anxiety and depression in RA patients is not inferior to that of bDMARDs [76]. RA patients taking methotrexate or leflunomide were found to have lower risk of self-harm behaviour compared to those taking hydroxychloroquine or biologics, patients on leflunomide being the lowest-risk group of having anxiety or depression [84]. One RCT proved that MTX, LEF and SLZ improve physical function, mental impairment and QoL in RA patients by measuring SF-36 and HAQ, the difference in mean or median HAQ-DI being − 0.22 at the 12- and 24-month period [85]. Another RCT proved the superior effect of LEF over placebo in improving bodily pain, functional status, PGA, SF-36 score and HAQ-DI. A better statistically significant result with MTX versus placebo was also found in the trial [86]. Microglial activation and corpus callosum were detected in a juvenile rodent model study and it also showed cognitive decline after 1 week and 8 weeks of methotrexate 0.5 mg/kg injection [87]. An improvement in HAQ-DI (mean 1.46 from baseline 1.63; p = 0.001) in 3 months is seen in RA patients treated with leflunomide [88].

bDMARDs

Depression as a comorbidity in RA patients before starting on bDMARDs can reduce the treatment response [31]. The BSRBR reported a DAS28 difference at 1-year follow-up for patients treated with bDMARDs as − 0.38, − 0.34 and − 0.32 in no, moderate and severe depression respectively measured by EQ5D [31]. Odd ratios (ORs) for a good treatment response at 1-year follow-up between no depression patients and moderate depression patients showed OR = 0.85 (95% CI 0.69, 1.04) whilst between no depression group and severe depression group showed OR = 0.62 (95% CI 0.45, 0.87) [31].

IL-6 has a significant relationship with major depressive disorder (MDD) [66], and IL-6 inhibitors are considered effective in selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) refractory major depression cases [67, 66, 68]. Sarilumab, by targeting IL-6, improves depression in RA patients [60]. It is also evident that sirukumab targeting IL-6 and reducing the CRP level improved major depressive symptoms [89]. An observational study showed a positive correlation between the FACIT-F score and depression (BDI scale) (linear regression β = 0.714 and β = 0.777) (p < 0.001). The percentage of RA patients with fatigue was reduced from 58.8 to 37.6% in 6 months after receiving tocilizumab (TCZ), reducing the FACIT-F scale by 5.4 ± 11.2 (p < 0.001) from baseline [90]. An improvement in HAQ-DI and PGA is also found in RA patients on TCZ [91]. A retrospective study showed depression remission (HAM-D < 7) in bDMARDs-treated young female RA patients [41]. Fiftty per cent improvement in depressive symptoms through glucose and lipid homeostasis is seen after 12-month treatment with infliximab [92].

Tumour necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) therapy has been shown to improve fatigue and reduce emotional stress and cognitive function [93]. A reduction in the level of fatigue (FACIT-F and SF-36) is reported by standardised mean difference − 0.42 (P < 0.00001) for TNFi and − 0.46 (P < 0.00001) for non-TNFi bDMARDs [47]. A small and moderate improvement in FACIT-F with TNFi (adalimumab, golimumab and certolizumab) and with non-TNFi biologics was found; the effect size (ES) was 0.36 (95% CI 0.21, 0.51) and 0.57 (95% CI 0.39, 0.75) respectively compared to placebo group [94].

tsDMARDs

Significant reductions in fatigue with JAK inhibitors tofacitnib and baricitinib were also proved in phase 3 clinical trials. The improvement in FACIT-F score was seen at 24 weeks for patients taking baricitinib 4 mg but no statistical significance with 2 mg baricitinib according to randomised controlled trials [47, 95]. ACR20, ACR50 and ACR70 response criteria were fulfilled in patients taking baricitinib 4 mg at week 12 [95]. In > 68% of RA patients treated with tofacitinib monotherapy, MTX + tofacitinib and adalimumab(ADA) + MTX in a phase IIIB/IV study, an overall improvement in QoL (FACIT-F, SF-36, PGA and HAQ-DI) was observed [96]. All three groups reported significant improvement in arthritis pain at week 6, least square mean (LSM) changes being − 22.6 in tofacitinib monotherapy, − 22.8 in the tofacitinib + MTX group and − 23.0 in the ADA + MTX group. Reduction in pain score among tofacitinib monotherapy patients was sustained at 3 months (p < 0.01), at 6 months (LSM change − 26.6, p < 0.05) and at 12 months (p < 0.05) [96]. Tofacitinib was proved to be superior to methotrexate in improving PROs in a phase 3 RCT [97]. The results from the SELECT-NEXT RCT showed that upadacitinib 15 mg or 30 mg in RA improved all PROs including SF-36, FACIT-F, PGA, pain VAS score, EMS and HAQ-DI in 12-week duration from baseline [98].

Conclusion

Depression is two times more prevalent in RA patients than in the general population, and it is also evident that not all patients are assessed for their mental well-being. Since a correlation between the severity of depression and the activity of RA is found, detecting and managing depression might optimise the care of RA patients. Among several tools that can measure mental health status and PROs, SF-36, VAS, PGA, HADs and HAQ-DI are the most commonly used measurements in rheumatology studies. However, it is still a challenge to choose the standard measurement tool to assess mental health within the limited time constraint in outpatient departments. There are observational studies looking at the cognitive function in RA patients taking a TNF-i. Further observational studies for early detection of anxiety and depression in RA patients using web-based questionnaires would be of help for both patients and clinicians. Regarding anti-rheumatic therapies, there is a growing body of research studies looking at the effect of bDMARDs on depression and cognitive function in RA patients. However, to differentiate between the affective and biological nature of depression in RA is an area that still needs more research studies.

References

Bąk E, Marcisz C, Borodzicz A, Sternal D, Krzemińska S. Comparison of health-related quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis during conventional or conventional plus biological therapy in Poland. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;13:223–31. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S189152.

Chancay M, Guendsechadze S, Blanco I. Types of pain and their psychosocial impact in women with rheumatoid arthritis. Women's Midlife Health. 2019;5:3.

“Rheumatoid arthritis in adults: management,” National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, July 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng100/chapter/Recommendations#the-multidisciplinary-team. [Accessed 30 October 2019].

“Depression in adults with a chronic physical health problem: recognition and management Clinical guideline [CG91],” National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, October 2009. [Online]. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg91. [Accessed 30 October 2019].

Zielinski M, Systrom D, Rose N. Fatigue, sleep, and autoimmune and related disorders. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1827. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01827.

Turesson C, O’Fallon W, Crowson C, Gabriel S, Matteson E. Extra-articular disease manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis: incidence trends and risk factors over 46 years. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:722–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.62.8.722.

Humphreys J, Verstappen S, Hyrich K, Chipping J, Marshall T, Symmons D. The incidence of rheumatoid arthritis in the UK: comparisons using the 2010 ACR/EULAR classification criteria and the 1987 ACR classification criteria. Results from the Norfolk Arthritis Register. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(8):1315–20. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201960.

Smolen J, Landewé R, Bijlsma J, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:960–77.

Song J, Song Y, Bae S, Cha H, Choe J, Choi S, Kim H, Kim J, Kim S, Lee C, Lee J, Lee S, Lee S, Lee S, Lee S, Park S, Park W, Shim S, Suh C, Yoo B, Yoo D, Yoo W. Treat-to-target strategy for asian patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: result of a multicenter trial in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2018;33(52):e346. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2018.33.e346.

Damjanov N, Radunovic G, Prodanovic S, Vukovic V, Milic V, Simic Pasalic K, Jablanovic D, Seric S, Milutinovic S, Gavrilov N. Construct validity and reliability of ultrasound disease activity score in assessing joint inflammation in RA: comparison with DAS-28. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/ker255.

Scott I, Machin A, Mallen C, Hider S. The extra-articular impacts of rheumatoid arthritis: moving towards holistic care. BMC Rheumatol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41927-018-0039-2.

“Living with Rheumatoid arthritis, NHS,” 28 August 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/rheumatoid-arthritis/living-with/. [Accessed 31 October 2019].

Covic T, Cumming S, Pallant J, Manolios N, Emery P, Conaghan P, Tennant A. Depression and anxiety in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: prevalence rates based on a comparison of the depression, anxiety and stress scale (DASS) and the hospital, anxiety and depression scale (HADS). BMC Psychiatry. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-6.

Morris A, Yelin E, Panopalis P, Julian L, Katz P. Long-term patterns of depression and associations with health and function in a panel study of rheumatoid arthritis. J Health Psychol. 2011;16(4):667–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105310386635.

“Depression,” 22 March 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression. [Accessed 30 October 2019].

Sturgeon J, Finan P, Zautra A. Affective disturbance in rheumatoid arthritis: psychological and disease-related pathways. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(9):532–42. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2016.112.

Intriago M, Maldonado G, Cardenas J, Rios C. Quality of life in Ecuadorian patients with established rheumatoid arthritis. Open Access Rheumatol Res Rev. 2019;11:199–205. https://doi.org/10.2147/OARRR.S216975.

Twigg S, Hensor E, Emery P, Tennant A, Morgan A. Patient-reported outcomes as predictors of change in disease activity and disability in early rheumatoid arthritis: results from the Yorkshire early arthritis register. J Rheumatol. 2017;44(9):1331–400. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.161214.

Straub R, Cutolo M. Psychoneuroimmunology—developments in stress research. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2018;168(3–4):76–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10354-017-0574-2.

Rezaei F, Doost H, Molavi H. Depression and pain in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: mediating role of illness perception. Egypt Rheumatol. 2014;36(2):57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejr.2013.12.007.

“Invisible Disease: Rheumatoid Arthritis and Chronic Fatigue Survey,” National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society, 16–22 June 2014. [Online]. Available: https://www.nras.org.uk/invisible-disease-rheumatoid-arthritis-and-chronic-fatigue-survey. [Accessed 30 October 2019].

Nikolaus S, Bode C, Taal E, Laar M. Fatigue and factors related to fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Arthritis Care Res Am Coll Rheumatol. 2013;65(7):1128–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21949.

Peterson S, Piercy J, Blackburn S, Sullivan E, Karyekar C, Li N. The multifaceted impact of anxiety and depression on patients with rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Rheumatol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41927-019-0092-5.

Korte S, Straub R. Fatigue in inflammatory rheumatic disorders: pathophysiological mechanisms. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58(5):v35–v50. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kez413.

Brigitta B. Pathophysiology of depression and mechanisms of treatment. Dialog Clin Neurosci. 2002;4(1):7–20.

Matcham F, Rayner L, Steer S, Hotopf M. The prevalence of depression in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology. 2013;52:2136–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/ket169.

Cojocaru M, Cojocaru I, Silosi I, Vrabie C, Tanasescu R. Extra-articular manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Med. 2010;5(4):286–91.

Straub R, Dhabhar F, Bijlsma J, Cutolo M. How psychological sress via hormones and nerve fibers may exacerbate rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:16–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.20747.

DiMatteo M, Lepper H, Croghan T. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2101–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101.

Katz P, Yelin E. Activity loss and the onset of depressive symptoms: Do some activities matter more than others? Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1194–202. https://doi.org/10.1002/1529-0131(200105)44:5<1194:AID-ANR203>3.0.CO;2-6.

Matcham F, Davies R, Hotopf M, Hyrich K, Norton S, Steer S, Galloway J. The relationship between depression and biologic treatment response in rheumatoid arthritis: an analysis of the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kex528.

El Miedany Y (eds) Patient reported outcome measures in rheumatic diseases. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing ISBN 978–3–319–32851–5, 2016.

Siemons L, Klooster P, Vonkeman H, van de Laar M, Glas C. Further optimization of the reliability of the 28-joint disease activity score in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(6):e100544. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0100544.

Hansen I, Andreasen R, van Bui HM, Emamifar A. The reliability of disease activity score in 28 joints–c-reactive protein might be overestimated in a subgroup of rheumatoid arthritis patients, when the score is solely based on subjective parameters. J Clin Rheumatol. 2017;23(2):102–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/RHU.0000000000000469.

Slama I, Allali F, Lakhdar T, El Kabbaj S, Medrare L, Ngeuleu A, Rkain H, Hajjaj-Hassouni N. Reliability and validity of CDAI and SDAI indices in comparison to DAS-28 index in Moroccan patients with rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-015-0718-8.

Morris A, Yelin E, Panopalis P, Julian L, Katz P. Long-term patterns of depression and associations with health and function in a panel study of rheumatoid arthritis. J Health Psychol. 2011;16:667–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105310386635.

Tugwell P, Boers M, Brooks P, Simon L, Strand V, Idzerda L. OMERACT: an international initiative to improve outcome. Trials. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-8-38.

Imran M, Saira Khan E, Ahmad N, Farman Raja S, Saeed M, Ijaz HI. Depression in rheumatoid arthritis and its relation to disease activity. Pak J Med Sci. 2015;31:393–7. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.312.6589.

Rathbun A, Reed G, Harrold L. The temporal relationship between depression and rheumatoid arthritis disease activity, treatment persistence and response: a systematic review. Rheumatology. 2013;52:1785–94. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kes356.

Englbrecht M, Alten R, Aringer M, Baerwald C, Burkhardt H, Eby N, Flacke J, Fliedner G, Henkemeier U, Hofmann M, Kleinert S, Kneitz C, Krüger K, Pohl C, Schett G, Schmalzing M, Tausche A, Tony H, Wendler J. New insights into the prevalence of depressive symptoms and depression in rheumatoid arthritis—Implications from the prospective multicenter VADERA II study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(5):e0217412. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0217412.

Miwa Y, Ikari Y, Hosonuma M, Hatano M, Hayashi T, Kasama T, Sanada K. A study on characteristics of rheumatoid arthritis patients achieving remission in depression with 6 months of bDMARDs treatment. Eur J Rheumatol. 2018;5(2):111–4. https://doi.org/10.5152/eurjrheum.2018.17147.

Matcham F, Scott I, Rayner L, Hotopf M, Kingsley G, Norton S, Scott D, Steer S. The impact of rheumatoid arthritis on quality-of-life assessed using the SF-36: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2014; 44:123–130. www.elsevier.com/locate/semarthrit

Nikiphorou E, Radner H, Chatzidionysiou K, Desthieux C, Zabalan C, van Eijk-Hustings Y, Dixon W, Hyrich K, Askling J, Gossec L. Patient global assessment in measuring disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the literature. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18(1):251. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-016-1151-6.

Jagpal A, O’Beirne R, Morris M, et al. Which patient reported outcome domains are important to the rheumatologists while assessing patients with rheumatoid arthritis? BMC Rheumatol. 2019;3:36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41927-019-0087-2.

Hewlett S, Kirwan J, Bode C, Cramp F, Carmona L, Dures E, Englbrecht M, Fransen J, Greenwood R, Hagel S, van de Laar M, Molto A, Nicklin J, Petersson I, Redondo M, Schett G, Gossec L. The revised bristol rheumatoid arthritis fatigue measures and the rheumatoid arthritis impact of disease scale: validation in six countries. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018;57(2):300–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kex370.

Rongen-van Dartel S, Repping-Wuts H, van Hoogmoed D, Knoop H, Bleijenberg G, van Riel P, Fransen J. Relationship between objectively assessed physical activity and fatigue in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: inverse correlation of activity and fatigue. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014;66(6):852–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22251.

Choy E. Effect of biologics and targeted synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs on fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58(5):v51–v5555. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kez389.

Gries K, Berry P, Harrington M, Crescioni M, Patel M, Rudell K, Safikhani S, Pease S, Vernon M. Literature review to assemble the evidence for response scales used in patient-reported outcome measures. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41687-018-0056-3.

Brennan F, McInnes I. Evidence that cytokines play. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(11):3537–45. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI36389.

Spies C, Straub R, Cutolo M, Buttgereit F. Circadian rhythms in rheumatology—a glucocorticoid perspective. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16(Suppl 2):S3. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar4687.

Furst D, Emery P. Rheumatoid arthritis pathophysiology: update on emerging cytokine and cytokine-associated cell targets. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53(9):1560–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/ket414.

Agonia I, Couras J, Cunha A, Andrade A, Macedo J, Sousa-Pinto B. IL-17, IL-21 and IL-22 polymorphisms in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cytokine. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2019.154813.

Euesden J, Matcham F, Hotopf M, Steer S, Cope A, Lewis C, Scott I. The relationship between mental health, disease severity, and genetic risk for depression in early rheumatoid arthritis. Psychosom Med. 2017;79(6):638–45. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000462.

Sattar N, McCarey D, Capell H, McInnes I. Explaining how “high-grade” systemic inflammation accelerates vascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation. 2003;108:2957–63. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000099844.31524.05.

Silman A, Pearson J. Epidemiology and genetics of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. 2002;4(3):S265–S272272. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar578.

Lee J, Kim H, Lee D, Son C. Oxidative stress is a convincing contributor to idiopathic chronic fatigue. Sci Rep. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-31270-3.

Dantzer R. Cytokine, sickness behavior, and depression. Neurol Clin. 2006;24(3):441–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ncl.2006.03.003.

GS Ebrahim Haroon. Inflammation, glutamate, and glia: a trio of trouble in mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42(1):193–21515. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2016.199.

Drake C, Boutin H, Jones M, et al. Brain inflammation is induced by co-morbidities and risk factors for stroke. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25(6):1113–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2011.02.008.

Crotti C, Biggioggero M, Becciolini A, Favalli E. Sarilumab: patient-reported outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2018;9:275–84. https://doi.org/10.2147/PROM.S147286.

Cutolo M. NEIRD: a neuroendocrine immune network beyond the rheumatic diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12439.

Cutolo M, Seriolo B, Craviotto C, Pizzorni C, Sulli A. Circadian rhythms in RA. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:593–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.62.7.593.

Miller A. Five things to know about inflammation and depression. Psychiatric Times. 2018;35(4):2018.

Maes M, Van Bockstaele D, Gastel A, Song C, Schotte C, Neels H, DeMeester I, Scharpe S, Janca A. The effects of psychological stress on leukocyte subset distribution in humans: evidence of immune activation. Neuropsychobiology. 1999;39(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000026552.

Tsuboi H, Minamida Y, Tsujiguchi H, Matsunaga M, Hara A, Nakamura H, Tsuboi H, Sakakibara H. Elevated levels of serum IL-17A in community-dwelling women with higher depressive symptoms. Behav Sci (Basel). 2018;8(11):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs8110102.

Felger J, Lotrich F. Inflammatory cytokines in depression: neurobiological mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Neuroscience. 2013;246:199–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.04.060.

Lindqvist D, Janelidze S, Hagell P, Erhardt S, Samuelsson M, Minthon L, Hansson O, Björkqvist M, Träskman-Bendz L, Brundin L. Interleukin-6 is elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid of suicide attempters and related to symptom severity. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66(3):287–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.01.030.

Yoshimura R, Kishi T, Iwata N. Plasma levels of IL-6 in patients with untreated major depressive disorder: comparison with catecholamine metabolites. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:2655–61. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S195379.

Pariante CM. Why are depressed patients inflamed? A reflection on 20 years of research on depression, glucocorticoid resistance and inflammation. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;27(6):554–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2017.04.001.

Meade T, Manolios N, Cumming S, Conaghan P, Katz A. Cognitive impairment in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Arthritis Care Res Am College Rheumatol. 2018;70(1):39–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23243.

Bartolini M, Candela M, Brugni M, Catena L, Mari F, Pomponio G, Provinciali L, Danieli G. Are behaviour and motor performances of rheumatoid arthritis patients influenced by subclinical cognitive impairments? A clinical and neuroimaging study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2002;20(4):491–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2016.112.

Shin S, Katz P, Wallhagen M, Julian L. Cognitive Impairment in Persons With Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64(8):1144–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21683.

Oláh C, Kardos Z, Andrejkovics M, Szarka E, Hodosi K, Domján A, Sepsi M, Sas A, Kostyál L, Fazekas K, Flórián A, Lukács K, Miksi A, Baráth Z, Kerekes G, Péntek M, Valikovics A, Tamási L, Bereczki D, Szekanecz Z. Assessment of cognitive function in female rheumatoid arthritis patients: associations with cerebrovascular pathology, depression and anxiety. Rheumatol Int. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-019-04449-8.

Said F, Betoni T, Magalhaes V, Nisihara R, Skare T. Rheumatoid arthritis and cognition dysfunction: lack of association with cumulative glucocorticoid use. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923973.2019.1679170.

Miwa Y, Isojima S, Saito M, Ikari Y, Kobuna M, Hayashi T, Takahashi R, Kasama T, Hosaka M, Sanada K. Comparative study of infliximab therapy and methotrexate monotherapy to improve the clinical effect in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Intern Med. 2016;55(18):2581–5. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.55.6872.

Yayikci Y, Karadag A. Effects of conventional and biological drugs used for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis on the quality of life and depression. Euras J Med. 2019;51(1):12–6. https://doi.org/10.5152/eurasianjmed.2018.18018.

Bai S, Guo W, Feng Y, Deng H, Li G, Nie H, Guo G, Yu H, Ma Y, Wang J, Chen S, Jing J, Yang J, Tang Y, Tang Z. Efficacy and safety of anti-inflammatory agents for the treatment of major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2019-320912.

Molero P, Ruiz-Estigarribia L, Lahortiga-Ramos F, Sánchez-Villegas A, Bes-Rastrollo M, Escobar-González M, Martínez-González M, Fernández-Montero A. Use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin and the risk of depression: the “Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra (SUN)” cohort. J Affect Disord. 2019;247:161–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.01.020.

Song Q, Fan C, Wang P, Li Y, Yang M, Yu S. Hippocampal CA1 βCaMKII mediates neuroinflammatory responses via COX-2/PGE2 signaling pathways in depression. J Neuroinflammation. 2018;15(1):338. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-018-1377-0.

Bauer I, Green C, Colpo G, Teixeira A, Selvaraj S, Durkin K, Zunta-Soares G, Soares J. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of aspirin and n-acetylcysteine as adjunctive treatments for bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.18m12200.

Qin D, Li Z, Li Z, Wang L, Hu Z, Lü L, Wang Z, Liu Y, Yin Y, Li Z, Hu X. Chronic glucocorticoid exposure induces depression-like phenotype in Rhesus macaque (Macaca Mulatta). Front Neurosci. 2019;13:188. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2019.00188.

Sanacora G, Treccani G, Popoli M. Towards a glutamate hypothesis of depression an emerging frontier of neuropsychopharmacology for mood disorders. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62(1):63–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.07.036.

Zhang W, Egashira N, Masuda S. Recent topics on the mechanisms of immunosuppressive therapy-related neurotoxicities. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(13):E3210. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20133210.

Pinho de Oliveira Ribeiro N, Rafael de Mello Schier A, Ornelas A, Pinho de Oliveira C, Nardi A, Silva A. Anxiety, depression and suicidal ideation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in use of methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, leflunomide and biological drugs. Compr Psychiatry 2013;54(8):1185–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.05.010.

Strand V, Scott D, Emery P, Kalden J, Smolen J, Cannon G, Tugwell P, Crawford B, Gro LRAI. Physical function and health related quality of life: analysis of 2-year data from randomized, controlled studies of leflunomide, sulfasalazine, or methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(4):590–601.

Tugwell P, Wells G, Strand V, Maetzel A, Bombardier C, Crawford B, Dorrier C, Thompson A. Clinical improvement as reflected in measures of function and health-related quality of life following treatment with leflunomide compared with methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: sensitivity and relative efficiency to detect a treatment e. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(3):506–14.

Wen J, Maxwell R, Wolf A, Spira M, Gulinello M, Cole P. Methotrexate causes persistent deficits in memory and executive function in a juvenile animal model. Neuropharmacology. 2018;139:76–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.07.007.

Tłustochowicz M, Kisiel B, Tłustochowicz W. “Quality of life and clinical outcomes in Polish patients with high activity rheumatoid arthritis treated with leflunomide (Arava®) in therapeutic program: a retrospective analysis of data from the PLUS study. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2019. https://doi.org/10.17219/acem/104548.

Zhou A, Lee Y, Salvadore G, Hsu B, Fonseka T, Kennedy S, McIntyre R. Sirukumab: a potential treatment for mood disorders? Adv Ther. 2017;34(1):78–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-016-0455-x.

Corominas H, Alegre C, Narváez J, Fernández-Cid C, Torrente-Segarra V, Gómez M, Pan F, Morlà R, Martínez F, Gómez-Centeno A, Ares L, Molina R, González-Albo S, Dalmau-Carolà J, Pérez-García C, Álvarez C, Ercole L, Terrancle M. Correlation of fatigue with other disease related and psychosocial factors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tocilizumab: ACT-AXIS study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(26):e15947. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000015947.

Biggioggero M, Crotti C, Becciolini A, Favalli E. Tocilizumab in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: an evidence-based review and patient selection. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2018;13:57–70. https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S150580.

Bekhbat M, Chu K, Le N, Woolwine B, Haroon E, Miller A, Felger J. Glucose and lipid-related biomarkers and the antidepressant response to infliximab in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018;98:222–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.09.004.

Mason A, Holmes C, Edwards C. Inflammation and dementia: Using rheumatoid arthritis as a model to develop treatments? Autoimmun Rev. 2018;17:919–25.

Chauffier K, Salliot C, Berenbaum F, Sellam J. Effect of biotherapies on fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51(1):60–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/ker162.

Kremer J, Schiff M, Muram D, Zhong J, Alam J, Genovese M. Response to baricitinib therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with inadequate response to csDMARDs as a function of baseline characteristics. RMD Open. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2017-000581.

Strand V, Mysler E, Moots R, Wallenstein G, DeMasi R, Gruben D, Soma K, Iikuni N, Smolen J, Fleischmann R. Patient-reported outcomes for tofacitinib with and without methotrexate, or adalimumab with methotrexate, in rheumatoid arthritis: a phase IIIB/IV trial. RMD Open. 2019;5(2):e001040. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2019-001040.

Strand V, Lee E, Fleischmann R, Alten R, Koncz T, Zwillich S, Gruben D, Krishnaswami S, Wallenstein G. Tofacitinib versus methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis: patient-reported outcomes from the randomised phase III ORAL Start trial. RMD Open. 2016;2(2):e000308. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2016-000308.

Strand V, Pope J, Tundia N, Friedman A, Camp H, Pangan A, Ganguli A, Fuldeore M, Goldschmidt D, Schiff M. Upadacitinib improves patient-reported outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response to conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: results from SELECT-NEXT. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21:272. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-019-2037-1.

Baker K, Isaacs J, Thompson B. "Living a normal life": a qualitative study of patients' views of medication withdrawal in rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Rheumatol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41927-019-0070-y.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Christopher Holroyd: Honoraria, Lilly. Member of speakers’ bureau, Lilly. Christopher J. Edwards: Honoraria, Abbvie, Biogen, BMS, Celgene, Fresenius, GSK, Janssen, Lilly, Mundipharma, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, UCB. Member of speakers’ bureau, Abbvie, Biogen, BMS, Celgene, Janssen, Lilly, Sanofi, Pfizer, Roche. Grants/research support, Abbvie, Biogen, Pfizer. May N. Lwin and Lina Serhal have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Digital Features

To view digital features for this article go to: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12424850.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Lwin, M.N., Serhal, L., Holroyd, C. et al. Rheumatoid Arthritis: The Impact of Mental Health on Disease: A Narrative Review. Rheumatol Ther 7, 457–471 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-020-00217-4

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-020-00217-4