Abstract

Background

Cumulative anticholinergic burden refers to the cumulative effect of multiple medications with anticholinergic properties. However, concomitant use of cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) and anticholinergic burden can nullify the benefit of the treatment and worsen Alzheimer’s disease (AD). A literature gap exists regarding the extent of the cumulative anticholinergic burden and associated risk factors in AD. Therefore, this study evaluated the prevalence and predictors of cumulative anticholinergic burden among patients with AD initiating ChEIs.

Methods

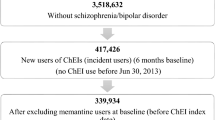

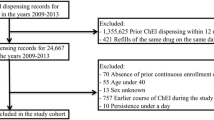

A retrospective longitudinal cohort study was conducted using the Medicare claims data involving parts A, B, and D from 2013 to 2017. The study sample included older adults (65 years and older) diagnosed with AD and initiating ChEIs (donepezil, rivastigmine, or galantamine). The cumulative anticholinergic burden was calculated based on the Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden scale and patient-specific dosing using the defined daily dose over the 1 year follow-up period after ChEI initiation. Incremental anticholinergic burden levels were dichotomized into moderate–high (sum of standardized daily anticholinergic exposure over a year (TSDD) score ≥ 90) versus low–no (score 0–89). The Andersen Behavioral Model was used as the conceptual framework for selecting the predictors under the predisposing, enabling, and need categories. A multivariable logistic regression model was used to evaluate the predictors of high-moderate versus low–no cumulative anticholinergic burden. A multinomial logistic regression model was also used to determine the factors associated with patients having moderate and high burdens compared to low/no burdens.

Results

The study included 222,064 older adults with AD with incident ChEI use (mean age 82.24 ± 7.29, 68.9% females, 83.6% White). Overall, 80.48% had some anticholinergic burden during the follow-up, with 36.26% patients with moderate (TSDD scores 90–499), followed by 24.76% high (TSDD score > 500), and 19.46% with low (TSDD score 1–89) burden categories. Predisposing factors such as age; African American, Asian, or Hispanic race; and need factors included comorbidities such as dyslipidemia, syncope, delirium, fracture, pneumonia, epilepsy, and claims-based frailty index were less likely to be associated with the moderate–high anticholinergic burden. The factors that increased the odds of moderate–high burden were predisposing factors such as female sex; enabling factors such as dual eligibility and diagnosis year; and need factors such as baseline burden, behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, depression, insomnia, urinary incontinence, irritable bowel syndrome, anxiety, muscle spasm, gastroesophageal reflux disease, heart failure, and dysrhythmia. Most of these findings remained consistent with multinomial logistic regression.

Conclusion

Four out of five older adults with AD had some level of anticholinergic burden, with over 60% having moderate–high anticholinergic burden. Several predisposing, enabling, and need factors were associated with the cumulative anticholinergic burden. The study findings suggest a critical need to minimize the cumulative anticholinergic burden to improve AD care.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Rodda J, Carter J. Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for symptomatic treatment of dementia. BMJ. 2012;344: e2986.

Foudah AI, Devi S, Alam A, Salkini MA, Ross SA. Anticholinergic effect of resveratrol with vitamin E on scopolamine-induced Alzheimer’s disease in rats: mechanistic approach to prevent inflammation. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1115721.

Konishi K, Hori K, Uchida H, Watanabe K, Tominaga I, Kimura M, et al. Adverse effects of anticholinergic activity on cognitive functions in Alzheimer’s disease. Psychogeriatrics. 2010;10(1):34–8.

Alzheimer’s Association. 2022 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimers Dement 2022;18.

Small G, Bullock R. Defining optimal treatment with cholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(2):177–84.

Farlow MR, Cummings JL. Effective pharmacologic management of Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Med. 2007;120(5):388–97.

Feinberg M. The problems of anticholinergic adverse effects in older patients. Drugs Aging. 1993;3(4):335–48.

Mintzer J, Burns A. Anticholinergic side-effects of drugs in elderly people. J Roy Soc Med. 2000;93(9):457–62.

Doraiswamy PM, Husain MM. Anticholinergic drugs and elderly people: a no brainer? Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(5):379–80.

Tune LE. Anticholinergic effects of medication in elderly patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 21):11–4.

López-Álvarez J, Sevilla-Llewellyn-Jones J, Agüera-Ortiz L. Anticholinergic drugs in geriatric psychopharmacology. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:1309.

By the 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15767.

Naugler CT, Brymer C, Stolee P, Arcese ZA. Development and validation of an improving prescribing in the elderly tool. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;7(2):103–7.

Gallagher P, Ryan C, Byrne S, Kennedy J, O’Mahony D. STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Person’s Prescriptions) and START (Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment). Consensus validation. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;46(2):72–83.

Risacher SL, McDonald BC, Tallman EF, West JD, Farlow MR, Unverzagt FW, et al. Association between anticholinergic medication use and cognition, brain metabolism, and brain atrophy in cognitively normal older adults. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(6):721–32.

Chen ZR, Huang JB, Yang SL, Hong FF. Role of cholinergic signaling in Alzheimer’s disease. Molecules. 2022;27(6):1816.

Lu CJ, Tune LE. Chronic exposure to anticholinergic medications adversely affects the course of Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11(4):458–61.

Sink KM, Thomas J 3rd, Xu H, Craig B, Kritchevsky S, Sands LP. Dual use of bladder anticholinergics and cholinesterase inhibitors: long-term functional and cognitive outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(5):847–53.

Hilmer SN, Mager DE, Simonsick EM, Cao Y, Ling SM, Windham BG, et al. A drug burden index to define the functional burden of medications in older people. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(8):781–7.

Rudolph JL, Salow MJ, Angelini MC, McGlinchey RE. The anticholinergic risk scale and anticholinergic adverse effects in older persons. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(5):508–13.

Carnahan RM, Lund BC, Perry PJ, Pollock BG, Culp KR. The Anticholinergic Drug Scale as a measure of drug-related anticholinergic burden: associations with serum anticholinergic activity. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;46(12):1481–6.

Gray SL, Anderson ML, Dublin S, Hanlon JT, Hubbard R, Walker R, et al. Cumulative use of strong anticholinergics and incident dementia: a prospective cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(3):401–7.

Boustani M, Campbell N, Munger S, Maidment I, Fox C. Impact of anticholinergics on the aging brain: a review and practical application. Aging Health. 2008. https://doi.org/10.2217/1745509X.4.3.311.

Lozano-Ortega G, Johnston KM, Cheung A, Wagg A, Campbell NL, Dmochowski RR, et al. A review of published anticholinergic scales and measures and their applicability in database analyses. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020;87: 103885.

Hanlon JT, Boudreau RM, Roumani YF, Newman AB, Ruby CM, Wright RM, et al. Number and dosage of central nervous system medications on recurrent falls in community elders: the Health, Aging and Body Composition study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(4):492–8.

Gray SL, LaCroix AZ, Blough D, Wagner EH, Koepsell TD, Buchner D. Is the use of benzodiazepines associated with incident disability? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(6):1012–8.

Chatterjee S, Walker D, Kimura T, Aparasu RR. Prevalence and factors associated with cumulative anticholinergic burden among older long-stay nursing home residents with overactive bladder. Drugs Aging. 2021;38(4):311–26.

Szabo SM, Gooch K, Schermer C, Walker D, Lozano-Ortega G, Rogula B, et al. Association between cumulative anticholinergic burden and falls and fractures in patients with overactive bladder: US-based retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5): e026391.

Coupland CAC, Hill T, Dening T, Morriss R, Moore M, Hippisley-Cox J. Anticholinergic drug exposure and the risk of dementia: a nested case-control study. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(8):1084–93.

Heath L, Gray SL, Boudreau DM, Thummel K, Edwards KL, Fullerton SM, et al. Cumulative antidepressant use and risk of dementia in a prospective cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(10):1948–55.

Lozano-Ortega G, Schermer CR, Walker DR, Szabo SM, Rogula B, Deighton AM, et al. Fall/fracture-related healthcare costs and their association with cumulative anticholinergic burden in people with overactive bladder. Pharmacoecon Open. 2021;5(1):45–55.

Gray SL, Dublin S, Yu O, Walker R, Anderson M, Hubbard RA, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of incident dementia or cognitive decline: prospective population based study. BMJ. 2016;352: i90.

Haddad YK, Kakara R, Marcum ZA. A comparative analysis of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and fall risk in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(5):1450–60.

Williams A, Sera L, McPherson ML. Anticholinergic burden in hospice patients with dementia. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2019;36(3):222–7.

Mate KE, Kerr KP, Pond D, Williams EJ, Marley J, Disler P, et al. Impact of multiple low-level anticholinergic medications on anticholinergic load of community-dwelling elderly with and without dementia. Drugs Aging. 2015;32(2):159–67.

Reppas-Rindlisbacher CE, Fischer HD, Fung K, Gill SS, Seitz D, Tannenbaum C, et al. Anticholinergic drug burden in persons with dementia taking a cholinesterase inhibitor: the effect of multiple physicians. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(3):492–500.

Ah YM, Suh Y, Jun K, Hwang S, Lee JY. Effect of anticholinergic burden on treatment modification, delirium and mortality in newly diagnosed dementia patients starting a cholinesterase inhibitor: a population-based study. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2019;124(6):741–8.

Tan ECK, Eriksdotter M, Garcia-Ptacek S, Fastbom J, Johnell K. Anticholinergic burden and risk of stroke and death in people with different types of dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;65(2):589–96.

Green AR, Reifler LM, Bayliss EA, Weffald LA, Boyd CM. Drugs contributing to anticholinergic burden and risk of fall or fall-related injury among older adults with mild cognitive impairment, dementia and multiple chronic conditions: a retrospective cohort study. Drugs Aging. 2019;36(3):289–97.

Bhattacharya R, Chatterjee S, Carnahan RM, Aparasu RR. Prevalence and predictors of anticholinergic agents in elderly outpatients with dementia. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2011;9(6):434–41.

Chatterjee S, Mehta S, Sherer JT, Aparasu RR. Prevalence and predictors of anticholinergic medication use in elderly nursing home residents with dementia: analysis of data from the 2004 National Nursing Home Survey. Drugs Aging. 2010;27(12):987–97.

Sura SD, Carnahan RM, Chen H, Aparasu RR. Prevalence and determinants of anticholinergic medication use in elderly dementia patients. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(10):837–44.

Joung KI, Shin JY, Cho SI. Features of anticholinergic prescriptions and predictors of high use in the elderly: population-based study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2019;28(12):1591–600.

Valladales-Restrepo LF, Duran-Lengua M, Machado-Alba JE. Potentially inappropriate prescriptions of anticholinergics drugs in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019;19(9):913–7.

Lee EK, Lee YJ. Prescription patterns of anticholinergic agents and their associated factors in Korean elderly patients with dementia. Int J Clin Pharm. 2013;35(5):711–8.

Palmer JB, Albrecht JS, Park Y, Dutcher S, Rattinger GB, Simoni-Wastila L, et al. Use of drugs with anticholinergic properties among nursing home residents with dementia: a national analysis of Medicare beneficiaries from 2007 to 2008. Drugs Aging. 2015;32(1):79–86.

Reinold J, Palese F, Romanese F, Logroscino G, Riedel O, Pisa FE. Anticholinergic burden before and after hospitalization in older adults with dementia: increase due to antipsychotic medications. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(6):868–80.

Kolanowski A, Fick DM, Campbell J, Litaker M, Boustani M. A preliminary study of anticholinergic burden and relationship to a quality of life indicator, engagement in activities, in nursing home residents with dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10(4):252–7.

Green AR, Reifler LM, Boyd CM, Weffald LA, Bayliss EA. Medication profiles of patients with cognitive impairment and high anticholinergic burden. Drugs Aging. 2018;35(3):223–32.

Fox C, Livingston G, Maidment ID, Coulton S, Smithard DG, Boustani M, et al. The impact of anticholinergic burden in Alzheimer’s dementia-the LASER-AD study. Age Ageing. 2011;40(6):730–5.

Watanabe S, Fukatsu T, Kanemoto K. Risk of hospitalization associated with anticholinergic medication for patients with dementia. Psychogeriatrics. 2018;18(1):57–63.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Standard Analytical Files: Identifiable Data Files. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/IdentifiableDataFiles/02_StandardAnalyticalFiles.asp (Accessed Nov 2021)

De Gage SB, Moride Y, Ducruet T, Kurth T, Verdoux H, Tournier M, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of Alzheimer’s disease: case-control study. BMJ. 2014;349: g5205.

Kang SY, Kim YJ, Jang W, Son KY, Park HS, Kim YS. Body mass index trajectories and the risk for Alzheimer’s disease among older adults. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):3087.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1495–9.

WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment 2020. Oslo: WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology; 2019.

Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10.

Kachru N, Carnahan RM, Johnson ML, Aparasu RR. Potentially inappropriate anticholinergic medication use in older adults with dementia. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2015;55(6):603–12.

Moore BJ, White S, Washington R, Coenen N, Elixhauser A. Identifying increased risk of readmission and in-hospital mortality using hospital administrative data: the AHRQ Elixhauser Comorbidity Index. Med Care. 2017;55(7):698–705.

Kim DH, Patorno E, Pawar A, Lee H, Schneeweiss S, Glynn RJ. Measuring frailty in administrative claims data: comparative performance of four claims-based frailty measures in the U.S. Medicare data. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75(6):1120–5.

SAS-STAT. SAS Institute, Inc. Cary, NC; 2001. Changes and Enhancements, Release 8.0.

Carnahan RM, Lund BC, Perry PJ, Chrischilles EA. The concurrent use of anticholinergics and cholinesterase inhibitors: rare event or common practice? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(12):2082–7.

Vaughan RM, Flynn R, Greene N. Anticholinergic burden of patients with dementia attending a Psychiatry of Later Life service. Ir J Psychol Med. 2022;39(1):39–44.

Campbell NL, Boustani MA, Lane KA, Gao S, Hendrie H, Khan BA, et al. Use of anticholinergics and the risk of cognitive impairment in an African American population. Neurology. 2010;75(2):152–9.

Narayan SW, Pearson SA, Litchfield M, Le Couteur DG, Buckley N, McLachlan AJ, et al. Anticholinergic medicines use among older adults before and after initiating dementia medicines. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85(9):1957–63.

Feng Z, Gasdaska A, Wang J, Haltermann III W, Howard JM. Can integrated care models deliver better outcomes for dually eligible beneficiaries? Health Affairs Forefront. 2022.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Guidelines. Dementia: Assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Copyright © NICE 2018; 2018.

Fiß T, Thyrian JR, Wucherer D, Aßmann G, Kilimann I, Teipel SJ, et al. Medication management for people with dementia in primary care: description of implementation in the DelpHi study. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:121.

Johansson G, Eklund K, Gosman-Hedström G. Multidisciplinary team, working with elderly persons living in the community: a systematic literature review. Scand J Occup Ther. 2010;17(2):101–16.

Rojo-Sanchís A, Vélez-Díaz-Pallarés M, García MM, Silveira ED, Vicedo TB, Cruz-Jentoft A. Reduction of anticholinergic burden in older patients admitted to a multidisciplinary geriatric acute care unit. Eur Geriatr Med. 2017;8(5–6):492–5.

van der Meer HG, Wouters H, van Hulten R, Pras N, Taxis K. Decreasing the load? Is a multidisciplinary multistep medication review in older people an effective intervention to reduce a patient’s drug burden index? Protocol of a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12): e009213.

Gitlin LN, Kales HC, Lyketsos CG. Managing behavioral symptoms in dementia using nonpharmacologic approaches: an overview. JAMA. 2012;308(19):2020.

Hanlon JT, Semla TP, Schmader KE. Alternative medications for medications in the use of high-risk medications in the elderly and potentially harmful drug-disease interactions in the elderly quality measures. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(12):e8–18.

Reuben DB, Herr KA, Pacala JT, Pollock BG, Potter JF, Semla TP. Geriatrics at your fingertips: American Geriatrics Society; 2016.

Abraha I, Cruz-Jentoft A, Soiza RL, O’Mahony D, Cherubini A. Evidence of and recommendations for non-pharmacological interventions for common geriatric conditions: the SENATOR-ONTOP systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. 2015;5(1): e007488.

Seitz DP, Brisbin S, Herrmann N, Rapoport MJ, Wilson K, Gill SS, et al. Efficacy and feasibility of nonpharmacological interventions for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia in long term care: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(6):503–6 (e2).

O'Neil ME, Freeman M, Christensen V, Telerant R, Addleman A, Kansagara D. A systematic evidence review of non-pharmacological interventions for behavioral symptoms of dementia. Washington (DC): Department of Veterans Affairs (US); 2011.

Siders C, Nelson A, Brown LM, Joseph I, Algase D, Beattie E, et al. Evidence for implementing nonpharmacological interventions for wandering. Rehabil Nurs. 2004;29(6):195–206.

Cardona V, Guilarte M, Luengo O, Labrador-Horrillo M, Sala-Cunill A, Garriga T. Allergic diseases in the elderly. Clin Transl Allergy. 2011;1(1):11.

Bousquet J, Bieber T, Fokkens W, Humbert M, Kowalski ML, Niggemann B, et al. Consensus statements, evidence-based medicine and guidelines in allergic diseases. Allergy. 2008;63(1):1–4.

Aronow WS, Fleg JL, Pepine CJ, Artinian NT, Bakris G, Brown AS, et al. ACCF/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. Circulation. 2011;123(21):2434–506.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No sources of funding were used to conduct this study or in preparation of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr Rajender R. Aparasu has received research funding from Astellas Inc., Incyte Corp., Gilead, and Novartis Inc. for projects unrelated to the current work. Ashna Talwar, Satabdi Chatterjee, Susan Abughosh, Jeffrey Sherer, and Michael Johnson have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the University of Houston Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects under the exempt category.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Material

The data on which this study is based are not available due to the CMS data use restrictions for research identifiable files.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: All authors. Acquisition of data: Ashna Talwar and Rajender R. Aparasu. Data analysis: Ashna Talwar. Data interpretation: All authors. Writing—original draft: Ashna Talwar. Writing—review &editing: All authors. Supervision: Rajender R. Aparasu.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Talwar, A., Chatterjee, S., Sherer, J. et al. Cumulative Anticholinergic Burden and its Predictors among Older Adults with Alzheimer’s Disease Initiating Cholinesterase Inhibitors. Drugs Aging 41, 339–355 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-024-01103-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-024-01103-2