Abstract

Background

Women Veterans’ numerical minority, high rates of military sexual trauma, and gender-specific healthcare needs have complicated implementation of comprehensive primary care (PC) under VA’s patient-centered medical home model, Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACT).

Objective

We deployed an evidence-based quality improvement (EBQI) approach to tailor PACT to meet women Veterans’ needs and studied its effects on women’s health (WH) care readiness, team-based care, and burnout.

Design

We evaluated EBQI effectiveness in a cluster randomized trial with unbalanced random allocation of 12 VAMCs (8 EBQI vs. 4 control). Clinicians/staff completed web-based surveys at baseline (2014) and 24 months (2016). We adjusted for individual-level covariates (e.g., years at VA) and weighted for non-response in difference-in-difference analyses for readiness and team-based care overall and by teamlet type (mixed-gender PC-PACTs vs. women-only WH-PACTs), as well as post-only burnout comparisons.

Participants

We surveyed all clinicians/staff in general PC and WH clinics.

Intervention

EBQI involved structured engagement of multilevel, multidisciplinary stakeholders at network, VAMC, and clinic levels toward network-specific QI roadmaps. The research team provided QI training, formative feedback, and external practice facilitation, and support for cross-site collaboration calls to VAMC-level QI teams, which developed roadmap-linked projects adapted to local contexts.

Main Measures

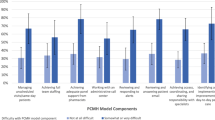

WH care readiness (confidence providing WH care, self-efficacy implementing PACT for women, barriers to providing care for women, gender sensitivity); team-based care (change-readiness, communication, decision-making, PACT-related QI, functioning); burnout.

Key Results

Overall, EBQI had mixed effects which varied substantively by type of PACT. In PC-PACTs, EBQI increased self-efficacy implementing PACT for women and gender sensitivity, even as it lowered confidence. In contrast, in WH-PACTs, EBQI improved change-readiness, team-based communication, and functioning, and was associated with lower burnout.

Conclusions

EBQI effectiveness varied, with WH-PACTs experiencing broader benefits and PC-PACTs improving basic WH care readiness. Lower confidence delivering WH care by PC-PACT members warrants further study.

Trial Registration

The data in this paper represent results from a cluster randomized controlled trial registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02039856).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Women Veterans are a numerical minority in the Veterans Health Administration (VA), chiefly reflecting historical differences in the composition of the military and thus the population of US Veterans upon military discharge. However, women are now the fastest growing segment of new VA users, with their own set of complex healthcare needs, including higher rates of service-connected disability and military sexual trauma (MST) in addition to gender-specific care needs that require gender-sensitive, trauma-informed care.1 As a result, VA has prioritized delivery of comprehensive women’s health (WH) services through gender-specific care models (e.g., WH clinics, designated WH providers) to meet their needs and mitigate gender disparities.2,3,4

In 2010, VA mounted efforts to nationally implement patient-centered medical homes, called Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACT),5 while parallel policy directives guided field-based requirements for delivering comprehensive PC for women Veterans.6 PACT delivers care to assigned patient panels through teamlets (provider, nurse, medical assistant, clerk), which are supported by a larger team (e.g., social workers, health coaches, clinical pharmacists). Consistent with VA policy, VAMCs may deliver PC to women Veterans in mixed-gender panels by PACT teamlets in general PC clinics (PC-PACTs) (Model 1) or in female-only panels seen by teamlets led by a designated WH provider (WH-PACTs). WH-PACTs may be co-located in general primary care (Model 2) or in a separate WH clinic (Model 3).

Given that the majority of patients in VA were (and still are) men, many VA primary care providers (PCPs) were historically less up-to-date on WH care delivery, including gender-specific services, and lacked experience addressing the needs of women Veterans with MST histories, which is concerning given that over 60% of women who routinely use VA PC have such histories.4,7 Team function was also a concern as women’s clinics were not appropriately staffed for women’s preventive care (e.g., chaperone use for gender-sensitive exams such as Pap smears) and staff were frequently shared across multiple clinics.8 Higher rates of burnout among providers in WH clinics vs. general PC clinics also raised concerns about how well PACT was working given the extra resources and specialized knowledge needed to care for complex women Veteran patients.9

In response to these challenges, we partnered with the VA Office of Women’s Health (OWH) to test the effectiveness of an evidence-based quality improvement (EBQI) approach to tailoring PACT to better meet women Veterans’ needs.10 EBQI is an implementation strategy that emphasizes a clinical-research partnership approach through multilevel stakeholder engagement, QI training, formative data feedback, technical support, and practice facilitation.11,12 EBQI has been shown to support implementation of evidence-based practices, including smoking cessation guidelines, depression collaborative care, and PACT implementation.13,14,15,16,17 In this paper, we report results of our cluster randomized trial of EBQI on WH care readiness, team-based care, and burnout.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

We evaluated effectiveness of EBQI in a parallel, two-arm cluster randomized controlled trial (cRCT) from 2014 to 2016, beginning approximately 4 years into PACT implementation.10 We randomly assigned 12 VA medical centers (VAMCs) to EBQI vs. routine PACT implementation in an unbalanced 2:1 ratio in each of 4 participating Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs) (8 experimental vs. 4 control VAMCs). Participating VAMCs were in urban and rural locations spanning nine states.10 All sites were part of the VA WH Practice-Based Research Network (WH-PBRN).18

Ethical Review

The study was approved by the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System Institutional Review Board (IRB); VA’s Central IRB determined sites were not engaged in research, permitting review by the home institution IRB only. Provider/staff survey data were collected in collaboration with in collaboration with the RAND Corporation, with study procedures approved by their IRB as well, with a waiver of documentation of consent. We obtained required approvals from VA labor management/unions and the VA National Center for Organizational Development (NCOD); however, NCOD disapproved baseline collection of burnout data (given persistently high rates nationwide), but allowed measure inclusion at 24 months (resulting in post-only comparisons).

EBQI Approach

We launched EBQI with in-person multilevel stakeholder meetings in each VISN (Fig. 1), using expert panel methods to come to consensus on QI priorities, summarized in roadmaps.19 We then trained two core members of each local team in EBQI and provided external practice facilitation over 24 months to help them use QI tools (e.g., process maps, measures) to conduct projects chosen from their VISN-specific QI roadmaps. We provided ongoing technical support, coaching/mentoring, and use of data from patient and provider/staff surveys and key stakeholder interviews19 to inform plan-do-study-act cycles within their projects. We supported across-EBQI-site calls and within-VAMC/VISN leadership reporting to share progress, culminating in capstone VISN-specific stakeholder meetings.10

Control VAMCs received standard policy guidance on PACT implementation and provision of comprehensive women’s health services that were disseminated to all VA healthcare facilities nationwide.

Sample

We surveyed all PC and WH-PACT teamlet members (PCPs, nurses, medical assistants, clerks) and extended PACT teams (e.g., social workers, pharmacists, health coaches) in participating VAMCs (September 2014–October 2016). We identified eligible PACT personnel using the VA Support Service Center (VSSC) Primary Care Reports for each geographically distinct station number and code. We complemented VSSC lists with VA Corporate Data Warehouse files to identify additional teamlets and team members not found in VSSC, obtaining staff identifiers, full vs. parttime status, gender, position title, and panel size. We excluded PACTs for special populations (e.g., spinal cord injury), resident-only teamlets, and home-based primary care.

Data Collection Procedures

At baseline and 24 months, providers and staff were contacted by email and provided with a brief study summary, answers to frequently asked questions, and a site-specific endorsement letter from a local leader, followed within 1–2 weeks by an email with a person-specific survey weblink and email-based follow-up of non-responders.

Measures

Characteristics of Participating VAMCs

We obtained urban/rural location from the VA Site Tracking database, which defines location based on the US Census. We determined academic affiliation using data validated by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations on medical school affiliations for each VAMC. Facility complexity is a VA-generated 5-point ordinal composite scale of patient volume, risk, scope of practice, teaching/research funding, and level of intensive care (e.g., 1a = most complex). Volume of women Veterans and total Veterans served were obtained from VSSC’s Primary Care Almanac.

Dependent Variables

Table 1 provides details on outcome measures, including Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for each scale. Measures included (1) WH care readiness (i.e., confidence providing WH care [clinicians only], self-efficacy implementing PACT for women, barriers to providing comprehensive care to women, gender sensitivity); (2) team-based care (i.e., clinic leadership change-readiness, team communication, decision-making, PACT-related QI activities, team functioning); and (3) PC burnout (24-month wave only due to VA oversight issues noted above). Measure scales and items are in Appendix 1.

Covariate Measures

We measured individual-level characteristics including provider type (staff vs. PCP), gender (female vs. male), age group (≥ 50 years vs. < 50), race (non-White vs. White), fulltime (vs. parttime), experience in WH care (i.e., having cared for at least 50% women patients for 3+ years), and length of VA service (years). We also measured practice environments, including clinic urban/rural location and whether they worked in a WH-PACT (yes/no).

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics of clinicians/staff were compared by EBQI vs. control using t-tests for continuous variables and Χ2 tests for categorical variables. Variables hypothesized to be associated with each outcome measure were evaluated for collinearity and subsequently included in each regression model in an intent-to-treat analysis.20,21

We weighted clinician/staff data for likelihood of enrollment and drop-out (attrition at 24 months) using baseline measures of gender, marital status, years worked in the VA, VAMC, and position type (e.g., physician vs. nurse) to better represent the target population of all PCPs and staff. Final weights were the product of non-response and attrition weights. We used difference-in-differences (DID) analyses using generalized linear models, adjusting for survey weights, time (baseline vs. 24 months), EBQI (vs. control), gender, race/ethnicity, years worked in VA, WH-PACT (vs. PC-PACT), clinician (vs. staff), fulltime (vs. parttime) employment, and percent of women Veterans receiving care at their VA. Given different PACT teamlet options for delivering women’s primary care, we also examined EBQI effects by type of PACT teamlet (PC-PACTs [Model 1] vs. WH-PACTs [Models 2–3]). We used STATA 15.1 for all analyses.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Participating VAMCs, Providers, and Staff

Participating VAMCs were predominantly in the Midwest (6) and Northeast (5) regions of the USA, with one site in the South (Table 2). All were academically affiliated, ranging in size (5040–35,285 Veteran users, 331–2622 women Veteran users, 2.3–13.2% women Veterans-to-total Veterans served in the prior year). All had mixed-gender PC clinics in addition to WH in PC or in a separate WH clinic, where a majority of women patients were seen (Tables 2 and 3). A higher percent of clinician/staff respondents were in WH-PACTs (45.8%) than PC-PACTs (33.5%) (Table 2). Response rates ranged from 30 to 36%. Figure 2 provides an overview of the CONSORT flow diagram of VISNs to VAMCs to clinicians/staff in this trial.

EBQI Implementation

Multilevel panels in each VISN came to consensus on 7–10 priorities (e.g., improving gender-specific preventive practices) (roadmaps available on request) and collaboratively decided on key WH personnel (e.g., WH medical director) to lead each VAMC’s local QI team. Teams subsequently chose projects to focus on during the 24-month EBQI period (Table 3). Facilitation calls were arranged for every 2–8 weeks, depending on local QI team availability, over 24 months. Calls focused on developing process maps, selecting measures, identifying and helping teams engage local process “owners,” providing technical support, and creating brief action plans for both QI and research teams before the next call. Formative feedback was provided an average of five times across EBQI VAMCs, and included data from local and all-EBQI VAMC reports.

Effectiveness of EBQI on Main Outcomes

Table 4 shows unadjusted comparisons of EBQI vs. control VAMC outcomes at baseline and 24 months. At baseline, control VAMCs had higher self-efficacy for implementing PACT for women (3.92 vs. 3.31, p = 0.027) and team functioning (4.10 vs. 3.70, p = 0.041) than EBQI VAMCs (Table 4). From baseline to 24 months, EBQI sites increased gender sensitivity, leadership change-readiness, team-based communication, decision-making, and PACT-related QI (all p < 0.05), and barriers decreased over time (p < 0.001). Control sites increased confidence delivering WH care, decision-making, and PACT-related QI (p < 0.05) and barriers decreased over time (p = 0.008). Unadjusted comparisons at 24 months revealed higher confidence in control vs. EBQI VAMCs (3.17 vs. 2.73, p = 0.013) (Table 4). Unadjusted 24-month burnout was not significantly different between EBQI and control VAMCs overall (19.2% vs. 24.4%, p = 0.38) or for PC-PACTs (22.4% vs. 21.0%, p = 0.88), but was marginally lower in WH-PACT EBQI sites (14% vs. 32%, p = 0.053) (not in table). (Appendix Table 2 shows unadjusted outcomes of PC-PACTs and WH-PACTs over time.)

Table 5 shows multivariate results of EBQI effectiveness analyses, adjusting for individual-level covariates. Study-wide, EBQI was associated with lower confidence in providing WH care (DID, −0.68; 95% CI, −1.20, −0.16; p < .05), improved gender sensitivity (DID, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.10, 0.57; p < .01), and marginal improvements in self-efficacy and team function.

Results for PC-PACT vs. WH-PACT teamlets demonstrated substantial variations in EBQI effects (Table 5). In PC-PACTs, EBQI was still associated with lower confidence in providing WH care (DID, −1.0; 95% CI [−1.70,−0.26]; p < 0.01), but greater self-efficacy implementing PACT for women (DID, 1.0 [0.01,1.94], p < 0.05) and higher gender sensitivity (DID, 0.35 [0.02,0.70]; p < 0.01). In contrast, in WH-PACTs, EBQI improved clinic leadership change-readiness (DID, 0.80 [0.26,1.34], p < 0.01), team-based communication (DID, 0.60 [0.04,1.17], p < 0.05), and team functioning (DID, 0.55 [0.10,1.01], p < 0.05). At 24 months, EBQI was also associated with significantly lower burnout in WH-PACTs vs. PC-PACTs, when we adjusted for individual-level covariates (adjusted OR, 0.324 [0.11–0.94], p = 0.038).

DISCUSSION

We found that EBQI had mixed impacts on WH care readiness and marginal improvements in self-efficacy in implementing PACT for women and PACT team functioning. However, significant and distinctive impacts of EBQI were seen when we examined effects among those already working in WH-PACTs vs. those working in PC-PACTs. In particular, the lower confidence in providing WH care reflected perceptions of clinicians and staff in PC-PACTs, not those in WH-PACTs. In PC-PACTs, EBQI significantly improved self-efficacy in implementation of PACT for women and gender sensitivity. In contrast, clinic leadership change-readiness, team-based communication, and team function significantly improved in WH-PACTs, with significantly lower burnout at 24 months. EBQI did not have significant effects on team-based decision-making, barriers to comprehensive care for women, or PACT-related QI activities.

We were initially surprised by the finding that EBQI was associated with lower confidence in delivering WH care. However, none of the QI roadmaps or local QI teams focused on confidence as a problem, especially since the majority of women Veterans at EBQI VAMCs were seen in WH-PACTs (two QI projects even focused on shepherding women patients to them). WH-PACTs are led by designated WH-PCPs, a designation associated with higher quality and better patient experience among women Veterans, which may have further contributed to the lack of emphasis on confidence.2,22 Local dissemination of EBQI activities PACT-wide may have also contributed to a better appreciation of knowledge deficits in WH care, thereby lowering confidence. Unadjusted comparisons demonstrated a significant increase in confidence at control VAMCs, which may have had more recent growth in the number of providers trained in the VA OWH’s WH “mini-residency” program (OWH has trained over 10,000 PCPs and nurses since the study’s inception (S. Haskell, personal communication)).23,24 Future research should explore ramifications of shifts in confidence for the PC workforce (e.g., cross-coverage issues when WH-PACTs are understaffed).

Like our findings around clinician confidence, overall, EBQI effects on gender sensitivity appear driven by PC-PACT rather than WH-PACT clinicians/staff. This improvement among PC-PACT clinicians/staff is important, as lack of gender sensitivity in VA has been associated with women Veterans’ delaying or forgoing care25 or care discontinuity (i.e., no return to primary care 3 years after initial visit).26 WH training and experience in working with other WH care professionals are strongly correlated with gender sensitivity, so EBQI may serve as an adjunct to routine training.27 Our findings regarding increased gender sensitivity are also consistent with the work of Fox et al., who found that EBQI enhanced gender sensitivity and knowledge in a study of cultural competence training for VA staff.28

While not significant overall, we also found that self-efficacy around implementing PACT for women improved only among PC-PACT clinicians/staff. For WH-PACTs, lack of improvement may be due to higher self-efficacy at the outset, fostered by more experience with women Veteran patients and more alignment with national VA WH care policy. PC-PACT clinicians/staff were likely less aware of this policy and may have felt less responsible for its implementation prior to EBQI. Since local QI teams were encouraged to broadly engage PACTs, EBQI may have increased awareness of what it takes to implement PACT for women due to fuller realization of its scope.

Significant improvements in perceived clinic leadership change-readiness and team-based communication among clinicians/staff in WH-PACTs (but not PC-PACTs) may be explained by WH leadership of local QI teams, which may have strengthened team-based communication and QI engagement.29 These leaders, in turn, involved an array of local personnel in their local QI projects, sharing knowledge and increasing collaborative problem-solving. Improvements in PACT team function in WH-PACTs may have a similar explanation in addition to the fact that two of the eight EBQI sites focused their QI projects explicitly on improving team function (e.g., virtual huddles).30 These improvements may also be associated with unmeasured characteristics of effective team functioning (e.g., shared goals and sense of purpose),31 which may be markers of more mature, fully realized PACTs.

Contrary to our expectation, burnout at 24 months was not lower at EBQI vs. control VAMCs. Our previous work suggests that EBQI reduces burnout, possibly by increasing empowerment of local QI teams, but this impact may take more time than the duration of this trial.15 However, we did find significantly lower burnout in WH-PACTs, where EBQI was concentrated and where job satisfaction may have been better with the focus on WH care delivery.32 Nationally, WH-PCPs have higher rates of burnout compared to general PCPs.9 While we lack baseline data enabling us to assess change over time, the differences between WH-PACTs and PC-PACTs is nonetheless notable. Given the crisis of burnout among VA providers more broadly,33,34 more attention should be devoted to spreading organizational strategies that successfully combat burnout, such as VA’s recent Reduce Employee Burnout and Optimize Organizational Thriving (REBOOT) national initiative.

Given EBQI’s focus on supporting local QI teams, we hypothesized that EBQI would improve team-based decision-making and PACT-related QI activities and simultaneously reduce barriers to implementation of PACT for women. We found no significant EBQI impacts in these measures. From PACT teamlet interviews, we learned that insufficient staffing, reliance on parttime providers, and access priorities, among other challenges, complicated PC delivery for women Veterans.8 These and other barriers we asked about (e.g., inadequate space, limited chaperones) may have been beyond the purview of local QI teams. Projects chosen by local QI teams also involved more people outside of PACT than within (e.g., improve mammography coordination), requiring less within-teamlet decision-making and engagement in QI among teamlet members.

This trial had several limitations. Low response rates—not uncommon among busy PC employees—are concerning; weighting for non-response may not have adequately addressed potential biases. We also lacked burnout measures at baseline, precluding adjustment for any baseline differences that may have been present. This trial also spanned VA’s “access crisis”35; some EBQI projects may have been adversely affected (e.g., due to divided attention and heightened organizational demands). We also relied on an unbalanced design to accommodate local variations in how EBQI might be deployed. However, these designs have lower statistical power to detect differences; significant findings demonstrate EBQI’s robustness. Outcomes may have benefited from working in the context of a PBRN where research-clinical dialogue may be better.36

In conclusion, we found EBQI to have mixed results overall, but with important and distinctive impacts for different PACT types (WH-PACTs vs. PC-PACTs). Specifically, EBQI increased gender sensitivity and self-efficacy in PC-PACTs, and improved clinic leadership change-readiness, team-based communication, and team functioning in WH-PACTs, with lower burnout at 24 months as well.

Within 1 year of launching EBQI, participating VAMCs began reporting early quality gains from their local QI projects to leadership, several of which were spread VISN-wide. These efforts led the VA OWH to adopt EBQI for use in low-performing VAs37 and OWH has since adopted EBQI for national rollout to continue the journey to tailor VA care to women Veterans’ needs, while we study impacts of EBQI on implementation of WH-focused evidence-based practices.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to inclusion of potentially sensitive disclosures, potential for subject re-identification, and lack of consent for data sharing from study participants.

References

Frayne SM, Phibbs CS, Saechao F, et al. Sourcebook: Women Veterans in the Veterans Health Administration. Volume 4: Longitudinal Trends in Sociodemographics, Utilization, Health Profile, and Geographic Distribution. 2018.

Bastian LA, Trentalange M, Murphy TE, et al. Association between women veterans’ experiences with VA outpatient health care and designation as a women’s health provider in primary care clinics. Women’s Health Issues. 2014;24(6):605-612.

deKleijn M, Lagro-Janssen AL, Canelo I, Yano EM. Creating a roadmap for delivering gender-sensitive comprehensive care for women Veterans: results of a national expert panel. Med Care. 2015;53(4 Suppl 1):S156.

Sheahan KL, Goldstein KM, Than CT, et al. Women Veterans’ healthcare needs, utilization, and preferences in Veterans Affairs primary care settings. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(Suppl 3):791-798.

Yano EM, Bair MJ, Carrasquillo O, Krein SL, Rubenstein LV. Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACT): VA’s journey to implement patient-centered medical homes. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:547-549.

Yano EM, Haskell S, Hayes P. Delivery of gender-sensitive comprehensive primary care to women veterans: implications for VA Patient Aligned Care Teams. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(2):703-707.

Klap R, Darling JE, Hamilton AB, et al. Prevalence of stranger harassment of women veterans at Veterans Affairs medical centers and impacts on delayed and missed care. Women’s Health Issues. 2019;29(2):107-115.

Chuang E, Brunner J, Mak S, et al. Challenges with implementing a patient-centered medical home model for women veterans. Women’s Health Issues. 2017;27(2):214-220.

Apaydin EA, Mohr DC, Hamilton AB, Rose DE, Haskell S, Yano EM. Differences in burnout and intent to leave between women’s health and general primary care providers in the veterans health administration. J Gen Intern Med. 2022:1-8.

Yano EM, Darling JE, Hamilton AB, et al. Cluster randomized trial of a multilevel evidence-based quality improvement approach to tailoring VA Patient Aligned Care Teams to the needs of women Veterans. Implement Sci. 2015;11:1-14.

Rubenstein LV, Stockdale SE, Sapir N, et al. A patient-centered primary care practice approach using evidence-based quality improvement: rationale, methods, and early assessment of implementation. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:589-597.

Hempel S, Bolshakova M, Turner BJ, et al. Evidence-based quality improvement: a scoping review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(16):4257-4267.

Yano EM, Rubenstein LV, Farmer MM, et al. Targeting primary care referrals to smoking cessation clinics does not improve quit rates: Implementing evidence‐based interventions into practice. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(5p1):1637-1661.

Chaney EF, Rubenstein LV, Liu C-F, et al. Implementing collaborative care for depression treatment in primary care: a cluster randomized evaluation of a quality improvement practice redesign. Implement Sci. 2011;6:1-15.

Meredith LS, Batorsky B, Cefalu M, et al. Long-term impact of evidence-based quality improvement for facilitating medical home implementation on primary care health professional morale. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):1-10.

Stockdale SE, Zuchowski J, Rubenstein LV, et al. Fostering evidence-based quality improvement for patient-centered medical homes: initiating local quality councils to transform primary care. Health Care Manage Rev. 2018;43(2):168-180.

Rubenstein LV, Meredith LS, Parker LE, et al. Impacts of evidence‐based quality improvement on depression in primary care: a randomized experiment. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(10):1027-1035.

Frayne SM, Carney DV, Bastian L, et al. The VA women’s health practice-based research network: amplifying women veterans’ voices in VA research. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:504-509.

Hamilton AB, Brunner J, Cain C, et al. Engaging multilevel stakeholders in an implementation trial of evidence-based quality improvement in VA women’s health primary care. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7(3):478-485.

Mickey R, Greenland S. A study of the impact of confounder-selection criteria on effect estimation. Am J Epi. 1987;737-737.

Gupta SK. Intention-to-treat concept: A review. Perspect Clin Res. 2011;2(3):109-112.

Baier Manwell L, McNeil M, Gerber MR, et al. Mini-residencies to improve care for women veterans: a decade of re-educating Veterans Health Administration primary care providers. J Women’s Health. 2022;31(7):991-1002.

Farkas AH, Merriam S, Frayne S, Hardman L, Schwartz R, Kolehmainen C. Retaining providers with women’s health expertise: Decreased provider loss among VHA Women’s Health Faculty Development Program attendees. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(Suppl 3):786-790.

Bean-Mayberry B, Bastian L, Trentalange M, et al. Associations between provider designation and female-specific cancer screening in women Veterans. Med Care. 2015;53(4 Suppl 1):S47.

Washington DL, Bean-Mayberry B, Riopelle D, Yano EM. Access to care for women veterans: delayed healthcare and unmet need. J General Intern Med. 2011;26:655-661.

Than CT, Washington DL, Vogt D, et al. Discontinuity of women veterans’ care in patient-centered medical homes: Does workforce gender sensitivity matter? Women’s Health Issues. 2022;32(2):173-181.

Than C, Chuang E, Washington DL, et al. Understanding gender sensitivity of the health care workforce at the Veterans Health Administration. Women’s Health Issues. 2020;30(2):120-127.

Fox AB, Hamilton AB, Frayne SM, et al. Effectiveness of an evidence-based quality improvement approach to cultural competence training: The Veterans Affairs’ Caring for Women Veterans Program. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2016;36(2):96.

Giannitrapani KF, Rodriguez H, Huynh AK, et al. How middle managers facilitate interdisciplinary primary care team functioning. Healthc (Amst). 2019:10-15.

Ovsepyan H, Chuang E, Brunner J, et al. Improving primary care team functioning through evidence based quality improvement: A comparative case study. Healthc (Amst). 2023;11(2):100691.

True G, Stewart GL, Lampman M, Pelak M, Solimeo SL. Teamwork and delegation in medical homes: Primary care staff perspectives in the Veterans Health Administration. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:632-639.

Olmos-Ochoa T, McCoy M, Cannedy S, Oishi K, Hamilton A, Canelo I. Stay interviews: An innovative method to monitor and promote primary care employee retention. AcademyHealth; 2022:

Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2020. Healthc (Amst). 2022:491-506.

Rinne ST, Mohr DC, Swamy L, Blok AC, Wong ES, Charns MP. National burnout trends among physicians working in the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:1382-1388.

West CP, Dyrbye LN, Satele DV, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Concurrent validity of single-item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in burnout assessment. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1445-1452.

Hayward RA. Lessons from the Rise—and Fall?—of VA Healthcare. Springer; 2017. p. 11-13.

Goldstein KM, Vogt D, Hamilton A, et al. Practice-based research networks add value to evidence-based quality improvement. Healthc (Amst). 2018:128-134.

Hamilton AB, Olmos-Ochoa TT, Canelo I, et al. Dynamic waitlisted design for evaluating a randomized trial of evidence-based quality improvement of comprehensive women’s health care implementation in low-performing VA facilities. Implement Sci Communications. 2020;1:1-9.

Holt DT, Armenakis AA, Feild HS, Harris SG. Readiness for organizational change: The systematic development of a scale. J Appl Behav Sci. 2007;43(2):232-255.

Meredith LS, Eisenman DP, Green BL, Basurto-Dávila R, Cassells A, Tobin J. System factors affect the recognition and management of post-traumatic stress disorder by primary care clinicians. Med Care. 2009;47(6):686.

Helfrich CD, Li Y-F, Sharp ND, Sales AE. Organizational readiness to change assessment (ORCA): development of an instrument based on the Promoting Action on Research in Health Services (PARIHS) framework. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):1-13.

Ohman‐Strickland PA, John Orzano A, Nutting PA, et al. Measuring organizational attributes of primary care practices: development of a new instrument. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(3p1):1257-1273.

Wageman R, Hackman JR, Lehman E. Team diagnostic survey: Development of an instrument. J Appl Behav Sci. 2005;41(4):373-398.

Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP, Schaufeli WB, Schwab RL. Maslach burnout inventory. Vol 21. Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA; 1986.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of Barbara Simon, MA, in survey development; Alissa Simon, MA, for study-wide human subjects’ protection consultation and support; Anneka Oishi, BA, for survey management support; and Kristina Oishi, BA, for project assistance. We thank the staff of Davis Research, LLC, of Calabasas, CA, for their survey expertise and assistance with survey pre-testing, interviewer training, survey conduct, and interfacing with the VA Veteran Crisis Line to ensure participant emotional safety. Above all, we are grateful for the participation of the women Veterans and VA leaders, providers, and staff who provided their survey and interview responses reported in this study. We would also like to acknowledge the editorial review and feedback of Chloe Bird, PhD, Senior Sociologist, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, and currently Program Director of the Center for Health Equity Research in the Department of Medicine at Tufts School of Medicine. Her time was supported through the VA HSR&D Center for the Study of Healthcare Innovation, Implementation & Policy at the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (Project # CIN 13-417).

Funding

This study was funded by the US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research & Development (HSR&D) Service (Project #CRE 12-026). Dr. Yano’s effort was funded by a VA HSR&D Senior Research Career Scientist Award (Project #RCS 05-195). Dr. Brunner’s time was supported in part at the time of the study by a predoctoral fellowship awarded by the NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS), UCLA Clinical Translational Science Institute (CTSI) (Grant Numbers TL1TR000121 and TL1TR001883). Dr. Hamilton’s time is supported by a VA HSR&D Research Career Scientist Award (Project #RCS 21-135). The trial was undertaken in VA facilities that were members of the VA Women’s Health Practice-Based Research Network (PI Susan Frayne, MD, MPH; Program Manager Diane Carney, MA) (Project #SDR 10-012). This work was done in partnership with VA Office of Women’s Health, Veterans Health Administration, Washington DC, through the Women Veterans’ Healthcare CREATE Initiative funded by VA HSR&D Service.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest:

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US Government.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior Presentations

Different facets of preliminary trial results have been presented at the VA Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) National Meeting (July 19, 2017) and at the AcademyHealth Dissemination & Implementation Conference in Washington DC (December 5, 2017; December 4, 2018).

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yano, E.M., Than, C., Brunner, J. et al. Impact of Evidence-Based Quality Improvement on Tailoring VA’s Patient-Centered Medical Home Model to Women Veterans’ Needs. J GEN INTERN MED (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-024-08647-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-024-08647-4