Abstract

Background

The Veterans Health Administration (VA) is the largest integrated health system in the US and provides access to comprehensive primary care. Women Veterans are the fastest growing segment of new VA users, yet little is known about the characteristics of those who routinely access VA primary care in general or by age group.

Objective

Describe healthcare needs, utilization, and preferences of women Veterans who routinely use VA primary care.

Participants

1,391 women Veterans with 3+ primary care visits within the previous year in 12 VA medical centers (including General Primary Care Clinics, General Primary Care Clinics with designated space for women, and Comprehensive Women’s Health Centers) in nine states.

Methods

Cross-sectional survey (45% response rate) of sociodemographic characteristics, health status (including chronic disease, mental health, pain, and trauma exposure), utilization, care preferences, and satisfaction. Select utilization data were extracted from administrative data. Analyses were weighted to the population of routine users and adjusted for non-response in total and by age group.

Key Results

While 43% had health coverage only through VA, 62% received all primary care in VA. In the prior year, 56% used VA mental healthcare and 78% used VA specialty care. Common physical health issues included hypertension (42%), elevated cholesterol (39%), pain (35%), and diabetes (16%). Many screened positive for PTSD (41%), anxiety (32%), and depression (27%). Chronic physical and mental health burdens varied by age. Two-thirds (62%) had experienced military sexual trauma. Respondents reported satisfaction with VA women’s healthcare and preference for female providers.

Conclusions

Women Veterans who routinely utilize VA primary care have significant multimorbid physical and mental health conditions and trauma histories. Meeting women Veterans’ needs across the lifespan will require continued investment in woman-centered primary care, including integrated mental healthcare and emphasis on trauma-informed, age-specific care, guided by women’s provider preferences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

The population of women Veterans within the Veterans Health Administration (VA) is growing rapidly, with important implications for primary care delivery. While a numerical minority of all users, the absolute number of women Veterans utilizing VA services is increasing more swiftly than that of men Veterans.1 Between 2000 and 2015, the number of women Veterans accessing VA primary care almost tripled to nearly 450,000. Women Veterans thus constitute an increasing share of all VA users, growing from 5% of total users in 2000 to 8% in 2015 with a projected increase to 11% by 2024.2,3 The women Veteran population using VA is also aging. Their age distribution is trimodal, with three peaks at ages 32, 53, and 91.1 These peaks represent different life stages, each with specific healthcare needs.

Given the historically lower enrollment of women in the military, the VA healthcare delivery system has not needed the staffing and resources to provide comprehensive care for a large population of women Veterans. However, as their numbers have risen, VA has invested heavily in program development and evaluation, redesigned service delivery, provider training, and infrastructure to improve women Veterans’ access to high-quality care.4 In 2010, VA established minimum women’s health service delivery requirements and laid the groundwork for provision of primary care at one location from a single provider with the clinical proficiencies to meet women’s needs.5 VA facilities now offer primary care services to women through one or more of the following models: mixed gender General Primary Care Clinics, Comprehensive Primary Care Clinics with designated space for women, and Comprehensive Women’s Clinics. Many facilities offer Comprehensive Primary Care Clinics with designated space for women, and Comprehensive Women’s Clinics in addition to General Primary Care Clinics. In 2020, Congress passed the Deborah Sampson Act to further close women’s healthcare gaps and advance research.6

Despite significant advances and investment in VA women’s care, women may still face access barriers, lack of continuity, and care coordination challenges when using VA services.7,8,9,10 A recent study highlighted limited availability of women’s health providers and services, inefficient referral processes for community-based care, harassment at VA facilities, and difficulty scheduling appointments.11 Although optimizing women-centered primary care has been a key part of VA’s efforts to address these issues, relatively little is known about the health status, utilization, preferences, or satisfaction of women Veterans who routinely use VA primary care. We used a multi-state practice-based survey of women Veterans who routinely use VA primary care to address this knowledge gap and inform evidence-based improvements in care for women generally and by age group.

METHODS

We used baseline data collected for a cluster randomized controlled trial that assessed an evidence-based quality improvement approach to tailor VA’s patient-centered medical home model (Patient Aligned Care Teams) to better meet women’s needs. Detailed study methods are reported elsewhere.12 The study recruited from 12 VA medical centers in nine states spanning four VA regional networks. The sites offered services through a mix of care models (two facilities with mixed gender General Primary Care Clinics, two facilities with General Primary Care Clinics and Comprehensive Primary Care Clinics with designated space for women, 1 facility with a Comprehensive Women’s Clinic, and 7 facilities with General Primary Care Clinics and Comprehensive Women’s Clinics). We defined women with 3+ visits in the previous year as “routine users” because three is the average annual number of primary care encounters among women VA users nationally.1 Using VA administrative data, we identified 4,307 women Veterans at participating facilities who had 3+ primary or women’s healthcare visits in the previous year. Participants may have also accessed non-VA care. At four rural sites with fewer eligible patients, all were selected for participation, while at the other, larger VA facilities participants were randomly selected. Among these women, 3,102 were eligible for interview and 1,395 completed a telephone survey using computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) between January and March 2015 (response rate 45%). The CATI survey captured data for all measures except for utilization of VA mental health, primary care-mental health integrated care (PC-MHI), emergency room, and hospitalization. This information was extracted from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), where all VA patient encounter data are stored. Women’s primary care model availability at each facility was assessed using Women’s Assessment Tool for Comprehensive Health (WATCH) survey data. WATCH assesses availability and delivery of comprehensive care for women Veterans at each VA primary care site annually.13 The study was approved by the VA Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Sociodemographic Characteristics

We collected age, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, marital status, number of children in household, education, employment, and health insurance status.

Physical Health

We collected information on physical and mental conditions, experiences, and behaviors shown to have a substantial influence on Veteran health and primary care services delivery.14,15,16,17,18,19 For each woman, we calculated the Seattle Index of Comorbidity (SIC), which captures patient-reported age, smoking status, and seven chronic medical conditions (pneumonia, diabetes, cancer, lung disease, heart attack, stroke, congestive heart failure).20 Scores range from 0 to 20–25 (age dependent); higher scores indicate more severe comorbidity.

Mental Health and Trauma

We used validated screeners for depression (Patient Health Questionnaire 2 or PHQ-2), anxiety (Generalized Anxiety Disorder 2 scale or GAD2), and the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PTSD Checklist or PCL).21,22,23 Self-rated overall health and pain were measured with the Veterans RAND 12-item Health Survey. 24 Alcohol use was measured with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Concise (AUDIT-C). 25 Scores range from 0 to 12; 3+ indicates disorder. Military sexual trauma (MST) was measured using the VA’s two-item screener, which assesses sexual harassment, unwanted sexual contact, and sexual coercion while in the military.26 Combat exposure was defined as having ever served in a combat or war zone, received hostile fire, or seen someone severely wounded or killed during military service.

Healthcare Utilization, Preferences, and Satisfaction

Utilization of VA and non-VA healthcare was assessed by asking sources of overall healthcare, women’s health, mental health, and specialty care in the last 12 months. We extracted prior year VA utilization information from VA CDW for mental health, primary care-mental health integrated care (PC-MHI), emergency room, and hospitalization.

We asked women’s preference for a male or female provider when accessing basic primary care (e.g., routine care for illnesses) and women-specific care (e.g., pelvic exams). Women rated the importance of having women-only health clinics at VA on a 4-point scale (1 = not at all important, 4 = extremely important).

Seven items from the Primary Care Satisfaction Survey for Women were used to measure satisfaction with VA provider knowledge and skill related to women-specific health issues.27 Responses ranged from strongly disagree to strongly agree and were averaged and then transformed onto a 0–100 scale, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction. The survey queried whether women would recommend VA care to others and whether they perceived VA women’s healthcare as better, the same, or worse than care provided outside VA.

Analysis

We conducted descriptive analysis for the overall sample and by age group. From the 1,395 patients who completed the survey, we excluded 4 with missing age information, for an analytical sample of 1,391. All analyses are weighted to the population of women routine users of VA primary care, and for sample design and to address potential non-response bias. Analyses were conducted using Stata Version 15 (College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC).

RESULTS

We report overall findings and findings by age. Mean age was 49.8 (± 14.3) years (Table 1). Most, 59%, were non-Hispanic White; 28% were non-Hispanic Black. The majority, 62%, were not married. Ten percent reported their sexual orientation as gay or bisexual and 2% reported transgender identity. Overall, 40% had a college or graduate degree and 44% were employed. More than half, 57%, had health insurance from a non-VA source.

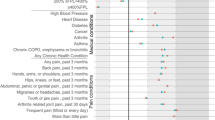

Physical Health

On average, 37% considered themselves in poor or fair health (Table 2). Overall, 72% reported at least one chronic condition, with the lowest prevalence among women aged 18–44 (45%) and the highest among women aged 65+ (96%). Hypertension and elevated cholesterol were the most common conditions. Median SIC score was two among women aged 18–44 and seven among women 65+. Pain interfered with normal work “a lot” or “all the time” for 35% of women, with interference highest (43%) among women aged 45–64. More than 20% of women Veterans scored 3+ on the AUDIT-C; the highest percentage (26%) was among women aged 18–44. Similarly, almost a quarter of all women identified as current smokers, with the highest percentage (26%) among women aged 45–64.

Mental Health and Trauma

Mental health comorbidities and experiences that may engender them, including sexual trauma and combat exposure, were common (Table 2). Half had at least one positive mental health screen; the percentage of positive screens was lowest (31%) among women 65+. Overall, 40% screened positive for symptoms of PTSD, 27% for depression, and 32% for anxiety. More than one-third reported at least one positive mental health screen and one chronic illness; mental and physical health comorbidity was highest (45%) among women aged 45–64. Experience of sexual trauma was common; 40% reported childhood sexual trauma and 62% reported MST. Women aged 45–64 reported the highest prevalence of childhood sexual trauma (44%) and MST (68%). Half of the women reported combat exposure; women aged 18–44 had the highest rate (70%).

Healthcare Utilization, Preferences, and Satisfaction

Overall, 62% of women routine users of VA primary care accessed all their healthcare in the VA (Table 3). Almost 80% had accessed specialty care exclusively from VA in the previous year. Across age groups, women Veterans had a median of two emergency room visits and one hospitalization at VA in the prior year. Just over half of women (57%) utilized mental or behavioral health services in the year prior to the survey. The percentage of women accessing mental or behavioral health services was approximately 60% among women aged 18–64 and lower (36%) among women 65 years and older. The median number of prior year mental health visits was six for women aged 65+ and eight for women in the younger age groups.

Across age groups, approximately 80–90% rated having a women-only provider/clinic as moderately-to-extremely important. Most women (70%) prefer female providers for women-specific care, while approximately half prefer female providers for general primary care. The mean patient satisfaction with provider score was 86.5/100 (Table 3). The vast majority (91%) would recommend VA to other women Veterans. While 60% considered women’s care provided in VA the same or better than care provided outside VA, 20% perceived outside care as better; this perception was most prevalent (30%) among the youngest age group.

DISCUSSION

We found that women Veterans who routinely use VA primary care and women’s health services have complex physical and mental health multi-morbidities, and that these vary by age in marked ways. Sexual trauma, during childhood and/or military service, was pronounced among nearly two-thirds of routine users, and combat exposure was also common. High healthcare utilization mapped to the level of self-reported healthcare need. Overall, women Veterans preferred women providers and women-only care environments, and they rated their VA care highly.

Our results, aligning with those of Lehavot et al. (2012), show higher prevalence of elevated cholesterol, diabetes, and cancer than among the general population of women. 28,29,30,31 Our results also show higher tobacco and alcohol use, both associated with trauma exposure and increased chronic illness.32,33,34 Consistent with Naylor (2019) and others, we found high prevalence of pain interference with daily living.35,36 Such chronic pain is correlated with functional impairment (e.g., involuntary unemployment, disability) and psychiatric pathologies.16,37 The prevalence of pain therefore requires continued efforts within primary care to routinely assess pain and link patients to multidisciplinary pain management interventions

Our findings reinforce prior studies showing extensive mental health needs and trauma exposure among women Veterans.17 Previous research shows that women Veterans have higher mental health comorbidity than non-Veteran women and that women generally have higher mental health comorbidity than men.31,38,39,40 Among women Veterans who routinely use VA primary care, childhood and military sexual trauma is a common experience that is associated with increased frequency and severity of psychological issues, alcohol use, impaired health status, chronic illness, and chronic pain.41,42,43,44,45,46,47 Additionally, our results show that a substantial percentage of women Veterans who routinely use VA primary care, particularly those aged 18–44, have experienced combat, which is linked to PTSD, depression, tobacco use, and alcohol misuse.34,48,49,50 While this study did not assess interpersonal violence, also related to adverse mental and physical health sequelae, other studies highlight its frequency among women Veterans, particularly those who utilize VA care.51,52 The prevalence of trauma and combat exposure among women who routinely use VA primary care reinforces the need to implement trauma-informed care across multiple clinical settings and optimize feasible options, including trauma-informed telehealth.53,54,55 VA has announced its broad support for trauma-informed care; implementation will require additional consultation time, provider training, effective mental health referral mechanisms, and attention to trust building within provider-patient relationships.56,57

Medical complexity among women who routinely use VA primary care is underscored by the prevalence of co-occurring chronic disease and mental health issues. Prior research has established links between mental health issues and chronic disease. For example, PTSD is a risk factor for developing heart disease and other chronic illnesses, and patients with anxiety or depression concurrent with chronic physical illness report more chronic disease symptoms than those with chronic disease alone.58,59,60,61 This suggests that accurate mental health diagnosis and care among women Veterans with chronic illness is key to understanding and managing chronic disease symptom burden.

Routine users of VA primary care report satisfaction with VA women’s health services have confidence in their providers and would recommend VA to other women Veterans. However, perception of the quality of women’s care provided in VA varies by age; a substantial minority of women in the youngest and middle age groups perceived women’s care provided outside VA as better than care provided inside. This perception warrants future study and continued investment in quality improvement. Women’s preference for receiving care in women-only settings and from female providers is evident. This aligns with previous research indicating that, within VA, quality of women’s care and satisfaction is higher among patients seen by designated women’s health providers and in women’s clinics.62,63 Women’s preferences should continue to influence facility planning.

Examining our results by age, we note distinct and varying health needs across the lifespan of women Veterans who routinely use VA primary care. For example, among women aged 18–44, the prevalence of elevated cholesterol (15%) is substantially higher than among the same age group of women in the general population (7.2%) and indicates a need for increased early prevention efforts. Additionally, women aged 18–44 had more combat exposure than women aged 45–65+. This high level of exposure is likely to continue now that all military positions, including active combat, are open to women. This may result in a need for increased deployment-related support, such as PTSD treatment, tailored to women. In addition, access to comprehensive, high-quality, and well-coordinated reproductive healthcare, including maternity care, is critical to women aged 18–44.

When looking at women aged 45–64, several important findings emerge. Concurrent physical and mental health issues peak in this age group. Women in this group most commonly report that pain interferes with their work “a lot/all” of the time, highlighting need for effective pain management across a large volume of women Veteran VA users. Also, sexual trauma is most prevalent among women aged 45–64, reinforcing the need for convenient access to mental health services and trauma-informed specialty care as women increase engagement in chronic disease (e.g., cardiovascular) care. Lastly, access to menopause-related care is critical in this age group.

Among women aged 65+, the prevalence of chronic illness mounts, requiring intensified management. The median medical comorbidity score (SIC) for women aged 65+ (7) is nearly twice that identified by DeSalvo (2005) among men VA users of the same age (4).64 Although prevalence of positive mental health screens is lowest among women aged 65+, almost one-third do screen positive, highlighting the need for elder care that focuses on mental healthcare in addition to chronic disease management.

Our study represents the first population-based survey of women Veterans who are VA routine primary care users. However, it does have limitations. To inform care delivery, provider training, and care coordination for women who rely on VA primary care, our sample includes only women with 3+ prior year primary care visits. While this visit frequency is higher than among insured women in the general public, prior research has demonstrated that women Veterans using VA services have greater health needs compared to non-Veteran women. 1,31,65 Our findings therefore do not represent women who do not routinely use VA primary care and may not inform service delivery in other settings. We used self-report measures, which are subject to recall and social desirability bias. However, self-report may also illuminate previously unreported symptoms, conditions, or experiences. Additionally, while we have data regarding model(s) of care available at each facility, we do not know the specific care model within which each participant received care. This limitation may undermine our ability to interpret some aspects of satisfaction. These limitations are balanced by strengths. The sample included diverse women from twelve VA sites representing different geographical regions, resource levels, complexity, and sizes. Our weighting procedures also improve sample generalizability and utility of our findings for informing practice and policy within VA.

This is the first paper to characterize healthcare needs, utilization patterns, and preferences among women Veterans who routinely use VA primary care services. Our findings highlight the importance of continued investment in women’s health clinical expertise and infrastructure within VA. They should inform ongoing improvements in women Veterans’ access to comprehensive services tailored to their needs at different stages of their lives. Continuing improvement will require a primary care delivery system capable of responding to the needs, utilization patterns, and preferences of women who rely on VA care, including sensitivity to their gender-specific and trauma-related needs.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because patient consent was not obtained to do so. Additionally, women Veterans are a small enough subset of all Veterans that the survey data could be used to re-identify participants, which would run counter to VA human subjects protections requirements.

References

Frayne SM, Phibbs CS, Saechao F, et al. Sourcebook: Women Veterans in the Veterans Health Administration. Volume 4: Longitudinal Trends in Sociodemographics, Utilization, Health Profile, and Geographic Distribution. 2018. Accessed 30 March 2021. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/WOMENSHEALTH/docs/WHS_Sourcebook_Vol-IV_508c.pdf

Eibner C, Krull H, Brown KM, et al. Current and projected characteristics and unique health care needs of the patient population served by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Rand Health Q. 2016;5(4):13.

National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. The Veteran Population Projection Model 2018 (VetPop2018). Accessed April 20, 2021. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/veteran_population.asp

U.S. General Accounting Office. Actions needed to ensure that female veterans have equal access to VA benefits. 1982. http://archive.gao.gov/pdf/119503.pdf

VHA DIRECTIVE 1330.01: Health Care for Women Veterans (Veterans Health Administration ) (2017).

The United States Senate Committee on Veterans’ Affairs. Tester’s Historic Deborah Sampson Act Signed Into Law. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://www.veterans.senate.gov/newsroom/minority-news/testers-historic-deborah-sampson-act-signed-into-law

Washington DL, Bean-Mayberry B, Riopelle D, Yano EM. Access to care for women veterans: delayed healthcare and unmet need. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26 Suppl 2:655-61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1772-z

Washington DL, Farmer MM, Mor SS, Canning M, Yano EM. Assessment of the healthcare needs and barriers to VA use experienced by women veterans: findings from the national survey of women Veterans. Med Care. 2015;53(4 Suppl 1):S23-31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000312

Evans EA, Tennenbaum DL, Washington DL, Hamilton AB. Why women veterans do not use VA-provided health and social services: Implications for health care design and delivery. J Humanist Psychol 2019;

Mattocks KM, Yano EM, Brown A, Casares J, Bastian L. Examining Women Veteran’s experiences, perceptions, and challenges with the veterans choice program. Med Care. 2018;56(7):557-560. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000933

Marshall V, Stryczek KC, Haverhals L, et al. The focus they deserve: improving Women Veterans’ Health Care Access. Womens Health Issues. 2021;31(4):399-407. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2020.12.011

Yano EM, Darling JE, Hamilton AB, et al. Cluster randomized trial of a multilevel evidence-based quality improvement approach to tailoring VA Patient Aligned Care Teams to the needs of women Veterans. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0461-z

Haskell S. 2017 WATCH: An update on the Implementation of Comprehensive Women’s Health. 2018:

Liu Y, Sayam S, Shao X, et al. Prevalence of and trends in diabetes among Veterans, United States, 2005-2014. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14:E135. doi:https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd14.170230

Jakob JM, Lamp K, Rauch SA, Smith ER, Buchholz KR. The impact of trauma type or number of traumatic events on PTSD diagnosis and symptom severity in treatment seeking veterans. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2017;205(2):83-86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000581

Naylor JC, Ryan Wagner H, Brancu M, et al. Self-reported pain in male and female iraq/afghanistan-era veterans: associations with psychiatric symptoms and functioning. Pain Med. 2017;18(9):1658-1667. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnw308

Runnals JJ, Garovoy N, McCutcheon SJ, et al. Systematic review of women veterans’ mental health. Womens Health Issues. 2014;24(5):485-502. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2014.06.012

Hoggatt KJ, Jamison AL, Lehavot K, Cucciare MA, Timko C, Simpson TL. Alcohol and drug misuse, abuse, and dependence in women veterans. Epidemiol Rev. 2015;37:23-37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxu010

Vimalananda VG, Miller DR, Christiansen CL, Wang W, Tremblay P, Fincke BG. Cardiovascular disease risk factors among women veterans at VA medical facilities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28 Suppl 2:S517-23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2381-9

Fan VS, Au D, Heagerty P, Deyo RA, McDonell MB, Fihn SD. Validation of case-mix measures derived from self-reports of diagnoses and health. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55(4):371-80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00493-0

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284-92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C

Lang AJ, Wilkins K, Roy-Byrne PP, et al. Abbreviated PTSD Checklist (PCL) as a guide to clinical response. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34(4):332-8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.02.003

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Monahan PO, Lowe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(5):317-25. doi:https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004

Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, Mazel RM. The RAND 36-Item Health Survey 1.0. Health Econ. 1993;2(3):217-27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.4730020305

Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol use disorders identification test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(16):1789-95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789

Kimerling R, Gima K, Smith MW, Street A, Frayne S. The Veterans Health Administration and military sexual trauma. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(12):2160-6. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2006.092999

Scholle SH, Weisman CS, Anderson RT, Camacho F. The development and validation of the primary care satisfaction survey for women. Womens Health Issues. 2004;14(2):35-50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2004.03.001

National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2019; Table 023. 2021. Accessed June 6, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/contents2019.htm

National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2019: Figure 012. 2021. Accessed June 6, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/contents2019.htm

National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2019; Table 014. 2021. Accessed June 21, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/contents2019.htm

Lehavot K, Hoerster KD, Nelson KM, Jakupcak M, Simpson TL. Health indicators for military, veteran, and civilian women. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(5):473-80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.006

National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2019: Table 020. Accessed June 20, 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/contents2019.htm

Johnson CS, Heffner JL, Blom TJ, Anthenelli RM. Exposure to traumatic events among treatment-seeking, alcohol-dependent women and men without PTSD. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23(5):649-52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20563

Gross GM, Bastian LA, Smith NB, Harpaz-Rotem I, Hoff R. Sex differences in associations between depression and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and tobacco use among veterans of recent conflicts. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2020;29(5):677-685. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2019.8082

Haskell SG, Brandt CA, Krebs EE, Skanderson M, Kerns RD, Goulet JL. Pain among veterans of operations enduring freedom and iraqi freedom: do women and men differ? Pain Med. 2009;10(7):1167-73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00714.x

Naylor JC, Wagner HR, Johnston C, et al. Pain intensity and pain interference in male and female Iraq/Afghanistan-era veterans. Womens Health Issues. 2019;29 Suppl 1:S24-S31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2019.04.015

Avluk OC, Gurcay E, Gurcay AG, Karaahmet OZ, Tamkan U, Cakci A. Effects of chronic pain on function, depression, and sleep among patients with traumatic spinal cord injury. Ann Saudi Med. 2014;34(3):211-6. doi:https://doi.org/10.5144/0256-4947.2014.211

Blosnich JR, Montgomery AE, Taylor LD, Dichter ME. Adverse social factors and all-cause mortality among male and female patients receiving care in the Veterans Health Administration. Prev Med. 2020;141:106272. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106272

Kroll-Desrosiers AR, Crawford SL, Moore Simas TA, Clark MA, Bastian LA, Mattocks KM. Rates and correlates of depression symptoms in a sample of pregnant veterans receiving Veterans Health Administration Care. Womens Health Issues. 2019;29(4):333-340. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2019.04.008

Lehavot K, Katon JG, Chen JA, Fortney JC, Simpson TL. Post-traumatic stress disorder by gender and veteran status. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(1):e1-e9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2017.09.008

MacIntosh HB, Menard AD. Where are we now? A consolidation of the research on long-term impact of child sexual abuse. J Child Sex Abus. 2021;30(3):253-257. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2021.1914261

Suris A, Lind L. Military sexual trauma: a review of prevalence and associated health consequences in veterans. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2008;9(4):250-69. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838008324419

Goldberg SB, Livingston WS, Blais RK, et al. A positive screen for military sexual trauma is associated with greater risk for substance use disorders in women veterans. Psychol Addict Behav. 2019;33(5):477-483. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000486

Kimerling R, Makin-Byrd K, Louzon S, Ignacio RV, McCarthy JF. Military sexual trauma and suicide mortality. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(6):684-691. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.10.019

Brignone E, Gundlapalli AV, Blais RK, et al. Differential risk for homelessness among US Male and Female Veterans with a positive screen for military sexual trauma. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(6):582-9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0101

Turner AP, Harding KA, Brier MJ, Anderson DR, Williams RM. Military sexual trauma and chronic pain in veterans. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;99(11):1020-1025. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0000000000001469

Sumner JA, Lynch KE, Viernes B, et al. Military sexual trauma and adverse mental and physical health and clinical comorbidity in women veterans. Womens Health Issues. 2021;https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2021.07.004

Creech SK, Swift R, Zlotnick C, Taft C, Street AE. Combat exposure, mental health, and relationship functioning among women veterans of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars. J Fam Psychol. 2016;30(1):43-51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000145

Hassija CM, Jakupcak M, Maguen S, Shipherd JC. The influence of combat and interpersonal trauma on PTSD, depression, and alcohol misuse in U.S. Gulf War and OEF/OIF women veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2012;25(2):216-9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21686

Cobb Scott J, Pietrzak RH, Southwick SM, et al. Military sexual trauma interacts with combat exposure to increase risk for posttraumatic stress symptomatology in female Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(6):637-43. doi:https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.13m08808

Dichter ME, Cerulli C, Bossarte RM. Intimate partner violence victimization among women veterans and associated heart health risks. Womens Health Issues. 2011;21(4 Suppl):S190-4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2011.04.008

Gerber MR, Iverson KM, Dichter ME, Klap R, Latta RE. Women veterans and intimate partner violence: current state of knowledge and future directions. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2014;23(4):302-9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2013.4513

Gerber MR, Elisseou S, Sager ZS, Keith JA. Trauma-informed telehealth in the COVID-19 era and beyond. Fed Pract. Jul 2020;37(7):302-308.

Leung LB, Rubenstein LV, Post EP, et al. Association of Veterans Affairs Primary Care Mental Health Integration with care access among Men and Women Veterans. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2020955. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.20955

Yano EM, Hamilton AB. Accelerating delivery of trauma-sensitive care: using multilevel stakeholder engagement to improve care for women veterans. Fam Syst Health. 2017;35(3):373-375. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/fsh0000288

Bergman AA, Hamilton AB, Chrystal JG, Bean-Mayberry BA, Yano EM. Primary care providers’ perspectives on providing care to women veterans with histories of sexual trauma. Womens Health Issues. 2019;29(4):325-332. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2019.03.001

Assistant Under Secretary for Clinical Services/Chief Medical Officer. Trauma-Infomed Care (TIC) Approach (VIEWS 5592562). 2021.

Vanitallie TB. Stress: a risk factor for serious illness. Metabolism 2002;51(6 Suppl 1):40-5. doi:https://doi.org/10.1053/meta.2002.33191

Weiss T, Skelton K, Phifer J, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder is a risk factor for metabolic syndrome in an impoverished urban population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33(2):135-42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.01.002

Katon W, Lin EH, Kroenke K. The association of depression and anxiety with medical symptom burden in patients with chronic medical illness. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29(2):147-55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.11.005

Ebrahimi R, Lynch KE, Beckham JC, et al. Association of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Incident Ischemic Heart Disease in Women Veterans. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6(6):642-651. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2021.0227

Bastian LA, Trentalange M, Murphy TE, et al. Association between women veterans’ experiences with VA outpatient health care and designation as a women’s health provider in primary care clinics. Womens Health Issues. 2014;24(6):605-12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2014.07.005

Bean-Mayberry B, Bastian L, Trentalange M, et al. Associations between provider designation and female-specific cancer screening in women Veterans. Med Care. 2015;53(4 Suppl 1):S47-54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000323

DeSalvo KB, Fan VS, McDonell MB, Fihn SD. Predicting mortality and healthcare utilization with a single question. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(4):1234-46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00404.x

Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Phillips RL, Jr., Rabin DL, Meyers DS, Bazemore AW. Projecting US primary care physician workforce needs: 2010-2025. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(6):503-9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1431

Acknowledgements

Contributors: Dr. Chloe Bird provided valuable feedback that was supported through the VA HSR&D Los Angeles Center of Innovation (Project #CIN 13-417). The authors thank the patient survey team, in particular Barbara Simon, MA, and Alissa Simon, MA, for their contributions to survey planning and instrument development; and Andrew Lanto, MA, for his work on sampling and analysis. We relied on the expertise of staff at Davis Research, LLC, of Calabasas, CA, who assisted with pre-testing and training, interfaced with VA Veteran Crisis Line to ensure participant emotional safety, and conducted the interviews. Above all, we are grateful for the participation of the women Veterans who helped with question testing and provided the information reported in this study.

Funding

This work was funded by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Services Research & Development (HSR&D) Service (Project #CRE 12-026) and supported by the VA Women’s Health Research Network (Project #SDR 10-012). The parent study—Implementation of Women's Health Patient Aligned Care Teams (Project #CRE 12-026)—is a cluster randomized trial registered in ClinicalTrials.gov #NCT02039856). Dr. Sheahan’s effort was covered by a VA Office of Academic Affiliations Health Services Research Postdoctoral Fellowship (TPH-2100). Dr. Yano’s effort was covered by a VA HSR&D Senior Research Clinical Scientist Award (Project #RCS 05-195). Dr. Chanfreau’s effort was covered by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations through an Advanced Postdoctoral Fellowship in Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) at the time of the study. This work was also supported by the Durham Center of Innovation to Accelerate Discovery and Practice Transformation (ADAPT) (Project #CIN 13-410) at the Durham VA Health Care System. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior Presentations:

NA

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sheahan, K.L., Goldstein, K.M., Than, C.T. et al. Women Veterans’ Healthcare Needs, Utilization, and Preferences in Veterans Affairs Primary Care Settings. J GEN INTERN MED 37 (Suppl 3), 791–798 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07585-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07585-3