Abstract

Purpose

To determine the association between age and retinal full-field electroretinographic (ERG) measures in companion (pet) dogs, an important translational model species for human neurologic aging.

Methods

Healthy adult dogs with no significant ophthalmic abnormalities were included. Unilateral full-field light- and dark-adapted electroretinography was performed using a handheld device, with mydriasis and topical anaesthesia. Partial least squares effect screening analysis was performed to determine the effect of age, sex, body weight and use of anxiolytic medication on log-transformed ERG peak times and amplitudes; age and anxiolytic usage had significant effects on multiple ERG outcomes. Mixed model analysis was performed on data from dogs not receiving anxiolytic medications.

Results

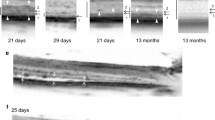

In dogs not receiving anxiolytics, median age was 118 months (interquartile range 72–140 months, n = 77, 44 purebred, 33 mixed breed dogs). Age was significantly associated with prolonged peak times of a-waves (dark-adapted 3 and 10 cds/m2 flash p < 0.0001) and b-waves (cone flicker p = 0.03, dark-adapted 0.01 cds/m2 flash p = 0.001). Age was also significantly associated with reduced amplitudes of a-waves (dark-adapted 3 cds/m2 flash p < 0.0001, 10 cds/m2 flash p = 0.005) and b-waves (light-adapted 3 cds/m2 flash p < 0.0001, dark-adapted 0.01 cds/m2 flash p = 0.0004, 3 cds/m2 flash p < 0.0001, 10 cds/m2 flash p = 0.007) and flicker (light-adapted 30 Hz 3 cds/m2 p = 0.0004). Within the Golden Retriever breed, these trends were matched in a cross-sectional analysis of 6 individuals that received no anxiolytic medication.

Conclusions

Aged companion dogs have slower and reduced amplitude responses in both rod- and cone-mediated ERG. Consideration of anxiolytic medication use should be made when conducting ERG studies in dogs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

American Veterinary Medical Association Veterinary Economics Division, 2020.

References

Klein R, Klein BEK, Linton KLP (2020) Prevalence of age-related maculopathy: the beaver dam eye study. Ophthalmology 127(4s):S122-s132

Owsley C et al (2022) How vision is impaired from aging to early and intermediate age-related macular degeneration: insights from ALSTAR2 baseline. Transl Vis Sci Technol 11(7):17

Fischer ME et al (2009) Multiple sensory impairment and quality of life. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 16(6):346–353

Brown RL, Barrett AE (2011) Visual impairment and quality of life among older adults: an examination of explanations for the relationship. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 66(3):364–373

Lee ATC et al (2020) Higher dementia incidence in older adults with poor visual acuity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 75(11):2162–2168

Lee CS et al (2019) Associations between recent and established ophthalmic conditions and risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 15(1):34–41

Baker ML et al (2009) Early age-related macular degeneration, cognitive function, and dementia: the cardiovascular health study. Arch Ophthalmol 127(5):667–673

Romaus-Sanjurjo D et al (2022) Alzheimer’s disease Seen through the eye: ocular alterations and neurodegeneration. Int J Mol Sci 23(5):2486

Christinaki E et al (2022) Retinal imaging biomarkers of neurodegenerative diseases. Clin Exp Optom 105(2):194–204

Moons L, De Groef L (2022) Multimodal retinal imaging to detect and understand Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Curr Opin Neurobiol 72:1–7

Chalkias IN et al (2021) Ocular biomarkers and their role in the early diagnosis of neurocognitive disorders. Eur J Ophthalmol 31(6):2808–2817

Merten N et al (2020) Macular ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer as a marker of cognitive and sensory function in midlife. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 75(9):e42–e48

Creel DJ (2019) Electroretinograms. Handb Clin Neurol 160:481–493

Marmoy OR, Viswanathan S (2021) Clinical electrophysiology of the optic nerve and retinal ganglion cells. Eye 35(9):2386–2405

Gotoh Y, Machida S, Tazawa Y (2004) Selective loss of the photopic negative response in patients with optic nerve atrophy. Arch Ophthalmol 122(3):341–346

Machida S et al (2008) Correlation between photopic negative response and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness and optic disc topography in glaucomatous eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49(5):2201–2207

Birch DG et al (2002) Quantitative electroretinogram measures of phototransduction in cone and rod photoreceptors: normal aging, progression with disease, and test-retest variability. Arch Ophthalmol 120(8):1045–1051

Birch DG, Anderson JL (1992) Standardized full-field electroretinography. Normal values and their variation with age. Arch Ophthalmol 110(11):1571–1576

Joshi NR, Ly E, Viswanathan S (2017) Intensity response function of the photopic negative response (PhNR): effect of age and test-retest reliability. Doc Ophthalmol 135(1):1–16

Neveu MM et al (2011) Electroretinogram measures in a septuagenarian population. Doc Ophthalmol 123(2):75–81

Kaeberlein M, Creevy KE, Promislow DE (2016) The dog aging project: translational geroscience in companion animals. Mamm Genome 27(7–8):279–288

Mowat FM et al (2008) Topographical characterization of cone photoreceptors and the area centralis of the canine retina. Mol Vis 14:2518–2527

Beltran WA et al (2014) Canine retina has a primate fovea-like bouquet of cone photoreceptors which is affected by inherited macular degenerations. PLoS ONE 9(3):e90390

Urfer SR, Greer K, Wolf NS (2011) Age-related cataract in dogs: a biomarker for life span and its relation to body size. Age 33(3):451–460

Donzel E, Arti L, Chahory S (2017) Epidemiology and clinical presentation of canine cataracts in France: a retrospective study of 404 cases. Vet Ophthalmol 20(2):131–139

Hernandez J et al (2016) Aging dogs manifest myopia as measured by autorefractor. PLoS ONE 11(2):e0148436

Heywood R, Hepworth PL, Van Abbe NJ (1976) Age changes in the eyes of the beagle dog. J Small Anim Pract 17(3):171–177

Panek WK et al (2020) Plasma neurofilament light chain as a translational biomarker of aging and neurodegeneration in dogs. Mol Neurobiol 57(7):3143–3149

Panek WK et al (2021) Plasma amyloid beta concentrations in aged and cognitively impaired pet dogs. Mol Neurobiol 58(2):483–489

Lewczuk P et al (2017) Cerebrospinal fluid Abeta42/40 corresponds better than Abeta42 to amyloid PET in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 55(2):813–822

Hoel JA et al (2021) Sustained gaze is a reliable in-home test of attention for aging pet dogs. Front Vet Sci 8:819135

Bray EE et al (2020) Cognitive characteristics of 8- to 10-week-old assistance dog puppies. Anim Behav 166:193–206

MacLean EL, Hare B (2018) Enhanced selection of assistance and explosive detection dogs using cognitive measures. Front Vet Sci 5:236

Snigdha S et al (2012) Age and distraction are determinants of performance on a novel visual search task in aged beagle dogs. Age 34(1):67–73

Studzinski CM et al (2006) Visuospatial function in the beagle dog: an early marker of cognitive decline in a model of human aging and dementia. Neurobiol Learn Mem 86(2):197–204

du PercieSert N et al (2020) The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol 18(7):e3000410

Creevy KE et al (2019) 2019 AAHA canine life stage guidelines. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 55(6):267–290

Ekesten B et al (2013) Guidelines for clinical electroretinography in the dog: 2012 update. Doc Ophthalmol 127(2):79–87

Freeman KS et al (2013) Effects of chemical restraint on electroretinograms recorded sequentially in awake, sedated, and anesthetized dogs. Am J Vet Res 74(7):1036–1042

Beale H, Ostrander EA (2012) Sizing up dogs. Curr Biol 22(9):R315–R316

Birch DG (1989) Clinical electroretinography. In: Fuller DG, Birch DG (eds) Ophthalmology clinics of North America. Assessment of visual function for the clinicians. WB Saunders Co, New York, pp 469–498

Mentzer AE et al (2005) Influence of recording electrode type and reference electrode position on the canine electroretinogram. Doc Ophthalmol 111(2):95–106

Lewis TW et al (2018) Longevity and mortality in Kennel Club registered dog breeds in the UK in 2014. Canine Genet Epidemiol 5:10

Passareli J et al (2021) Comparison among TonoVet, TonoVet Plus, Tono-Pen Avia Vet, and Kowa HA-2 portable tonometers for measuring intraocular pressure in dogs. Vet World 14(9):2444–2451

Weleber RG (1981) The effect of age on human cone and rod ganzfeld electroretinograms. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 20(3):392–399

Pasmanter N et al (2022) Use of extended protocols with nonstandard stimuli to characterize rod and cone contributions to the canine electroretinogram. Doc Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10633-022-09866-y

Jorge L et al (2019) Is the retina a mirror of the aging brain? Aging of neural retina layers and primary visual cortex across the lifespan. Front Aging Neurosci 11:360

Dastiridou A et al (2021) Age and signal strength-related changes in vessel density in the choroid and the retina: an OCT angiography study of the macula and optic disc. Acta Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.15028

Silva MF et al (2021) Simultaneous changes in visual acuity, cortical population receptive field size, visual field map size, and retinal thickness in healthy human aging. Brain Struct Funct 226(9):2839–2853

Tillman MA, Panorgias A, Werner JS (2016) Age-related change in fast adaptation mechanisms measured with the scotopic full-field ERG. Doc Ophthalmol 132(3):201–212

Jackson GR et al (2006) Impact of aging and age-related maculopathy on inactivation of the a-wave of the rod-mediated electroretinogram. Vis Res 46(8–9):1422–1431

Panorgias A et al (2017) Senescent changes and topography of the dark-adapted multifocal electroretinogram. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 58(2):1323–1329

Paulsen AJ et al (2021) Generational differences in the 10-year incidence of impaired contrast sensitivity. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 28(2):175–182

Varadaraj V et al (2021) Association of vision impairment with cognitive decline across multiple domains in older adults. JAMA Netw Open 4(7):e2117416

Violette NP et al (2022) Effects of gabapentin and trazodone on electroretinographic responses in clinically normal dogs. Am J Vet Res. https://doi.org/10.2460/ajvr.22.03.0047

Jay AR et al (2013) Pharmacokinetics, bioavailability, and hemodynamic effects of trazodone after intravenous and oral administration of a single dose to dogs. Am J Vet Res 74(11):1450–1456

Bossini L et al (2012) Off-label uses of trazodone: a review. Expert Opin Pharmacother 13(12):1707–1717

Dupanloup A, Osinchuk S (2021) Relationship between the ratio of optic nerve sheath diameter to eyeball transverse diameter and morphological characteristics of dogs. Am J Vet Res 82(8):667–675

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge statistical support provided by the University of Wisconsin Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers K08EY028628 and P30EY016665], an Unrestricted Grant from Research to Prevent Blindness Inc. to the UW-Madison Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, a pilot grant from the University of Wisconsin Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences donor funds, and the Dr. Kady M. Gjessing and Rhanna M. Davidson Distinguished Chair in Gerontology. The sponsors had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving animals were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution or practice at which the studies were conducted.

Statement of human rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Statement on the welfare of animals

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Salzman, M.M., Merten, N., Panek, W.K. et al. Age-associated changes in electroretinography measures in companion dogs. Doc Ophthalmol 147, 15–28 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10633-023-09938-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10633-023-09938-7