Abstract

Cellular studies have demonstrated a protective role of mitochondrial hexokinase against oxidative insults. It is unknown whether HK protective effects translate to the in vivo condition. In the present study, we hypothesize that HK affects acute ischemia–reperfusion injury in skeletal muscle of the intact animal. Male and female heterozygote knockout HKII (HK+/-), heterozygote overexpressed HKII (HKtg), and their wild-type (WT) C57Bl/6 littermates mice were examined. In anesthetized animals, the left gastrocnemius medialis (GM) muscle was connected to a force transducer and continuously stimulated (1-Hz twitches) during 60 min ischemia and 90 min reperfusion. Cell survival (%LDH) was defined by the amount of cytosolic lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity still present in the reperfused GM relative to the contralateral (non-ischemic) GM. Mitochondrial HK activity was 72.6 ± 7.5, 15.7 ± 1.7, and 8.8 ± 0.9 mU/mg protein in male mice, and 72.7 ± 3.7, 11.2 ± 1.4, and 5.9 ± 1.1 mU/mg in female mice for HKtg, WT, and HK+/-, respectively. Tetanic force recovery amounted to 33 ± 7% for male and 17 ± 4% for female mice and was similar for HKtg, WT, and HK+/-. However, cell survival was decreased (p = 0.014) in male HK+/- (82 ± 4%LDH) as compared with WT (98 ± 5%LDH) and HKtg (97 ± 4%LDH). No effects of HKII on cell survival was observed in female mice (92 ± 2% LDH). In conclusion, in this mild model of acute in vivo ischemia–reperfusion injury, a partial knockout of HKII was associated with increased cell death in male mice. The data suggest for the first time that HKII mediates skeletal muscle ischemia–reperfusion injury in the intact male animal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The glycolytic enzyme hexokinase (HK) has appeared as one of the main gatekeepers of mitochondria-induced cell death in cellular studies [23]. Binding of HK to mitochondria protects against cell death induced by oxidative stress [5, 9, 17, 18, 20]. Mitochondrial association of HK is also likely one of the major mechanisms allowing unrestricted growth of advanced cancer cells, due to the mitochondrial bound HK-induced protection against apoptosis [22]. Translocation of HK to mitochondria may also constitute part of the cardioprotective phenotype of ischemic preconditioning in the isolated heart [10, 30, 33, 34].

Surprisingly, almost all studies on the protective role of HK against cell death have been performed in cells using either H2O2 as the oxidative injury stimulus or calcium overload [3, 17, 18, 24]. It is unknown at present whether the observed protective effects of HK against oxidative stress in cellular studies translate to the intact animal. To this end, the present study aimed to examine whether HK is a determinant of acute, in vivo ischemia–reperfusion (I/R) injury.

There are four mammalian HK isozymes: HKI, HKII, HKIII, and HKIV. Since skeletal muscle contains primarily HKII, which is the HK isozyme involved in ischemic preconditioning [10], it provides the ideal opportunity to test, in vivo, the role of HK in I/R injury. In addition, skeletal muscle allows for direct force measurements, due to its singular origin and tendon and one line of pull, presenting an ideal model to evaluate functional performance following I/R interventions.

To study alterations in the level of HK, we make use of two different HKII genotypes: the C57Bl/6 mice with a partial deletion of HKII [12; HK+/-] as well as mice overexpressing HKII (HKtg) [2]. These mice are reported to have a 50% decrease (HK+/-) and a 350% increase (HKtg) in HKII content relative to wild-type (WT) gastrocnemius muscles [8]. We applied the twitch-stimulated I/R model that closely mimics prolonged noncontracting protocols, as reported by Welsh and Lindinger [27] for the rat hindlimb. The consummate test of contractile integrity of a muscle is its ability to develop force. Our first goal was to examine whether differences in the amount of (mitochondrial) HK affect functional recovery following I/R of the gastrocnemius muscle. Secondly, in alignment with many cellular studies showing HK’s protective effects against cell death, the role of HK in muscle viability following acute I/R insult was studied. Finally, it is known that the sensitivity towards I/R injury may differ between male and female, with usually reduced injury for females [19, 26]. It is unknown whether possible HK protective effects are also gender-dependent. Thus, our third goal examined whether possible effects of HKII on I/R injury differed between male and female mice.

Methods

Animals

C57Bl/6 HK+/- and HKtg mice were obtained from Vanderbilt University, Nashville (generous gift of Dr. David H. Wasserman). The HK+/- mice were first described by Heikkinen et al. [12] and have a partial deletion to the HKII gene; the HKtg mice contain a HKII transgene composed of the human HKII cDNA driven by the rat muscle creatine kinase promoter [2]. HK+/- and HKtg were initially bred with wild-type C57Bl/6 mice (Jackson Laboratories) and subsequently by wild-type offspring, which were used for this investigation. The wild-type animals in the present study were all littermates of the HK+/- breeding colony. Genotyping was performed with the polymerase chain reaction on genomic DNA obtained and isolated from toe biopsies, as described before [11, 12]. Six groups (n = 7 each) of mice were studied at 4–5 months of age: male and female WT, HK+/-, and HKtg. Housing conditions entailed 12 h dark/12 h light cycle, and water and food were provided ad libitum. Mice received the Rat and Mouse Breeder and Grower Expanded standard chow CRM (SDS; Special Diet Services Ltd., Witham, England). All experiments were approved by the animal ethics committee of the Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Preparation

Animals were anesthetized with ketamine (125 mg/kg), medetomidine (0.2 mg/kg), and atropine (0.5 mg/kg), as reported previously [31]. Anesthesia was maintained throughout the experiment with 20 mg/kg/45 min ketamine, 0.02 mg/kg/45 min medetomidine, and 0.03 mg/kg/45 min atropine. All animals received 1 ml saline solution subcutaneous in the neck prior to experimentation. Body temperature during the experiment was maintained at 37 ± 1°C with the use of rectal temperature monitoring, a temperature-controlled heating pad, and an infrared lamp. After anesthesia was induced, a tracheotomy was performed, and mechanical ventilation started (50% O2/50% N2; tidal volume = 8 ml/kg; respiration rate 120/min; Hugo Sachs Minivent). For the surgical preparation of the in situ stimulation, the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle (GM) of the left hindleg was prepared free from surrounding tissue, leaving the origin on the femur and the blood supply intact. Distally, the Achilles tendon was cut and attached through a metal hook to a force transducer as described before [32]. The femur was fixed with a metal clamp. Muscle optimum length was permanently kept at the length for which the twitch has its maximum amplitude determined using twitch contractions at different lengths of the muscle–tendon complex [6]. The muscle–tendon complex was stimulated via the severed sciatic nerve (1.5–2.5 V, 0.4 ms), with only the branch leading to the GM left intact. Muscle temperature during the experiment was kept at 37°C by a custom-made glass water chamber positioned around the GM. Intermittent administration (approximately two times per hour) of paraffin oil throughout the experiment prevented drying of muscle and tendon. Ischemia was made feasible by placing a ligature around the surgically prepared femoral artery of the left hindleg, with ischemia initiated by adding weights (12 g) to the ligature. Reperfusion was started by releasing the weights and removing the ligature.

Validation of ischemia and reperfusion

A laser speckle imaging (LSI) technique was used to assess limb perfusion [4, 7] during ischemia and reperfusion instigated by the weight-carrying ligature in separate experiments (n = 3). For LSI measurements, a commercially available system was used (Moor Instruments Ltd, United Kingdom). A 785-nm class 1 laser diode was employed for illumination of the tissue, and directly reflected light by the tissue surface was blocked by a tunable polarizer placed in front of the lens system. Laser speckle images were captured using a 576 × 768 pixels grayscale CCD camera at a frame rate of 25 Hz and converted to pseudo-color images, where the level of perfusion was scaled from blue (low perfusion) to red (high perfusion). Following induction of anesthesia, the animals were ventilated, and a ligature positioned around the femoral artery of the left hindleg. Subsequently, the triceps surae complex was exposed of both hindlegs and the LSI positioned about 50 cm above the animal such that both hindlegs could be monitored. For maintenance of muscle temperature during monitoring of leg perfusion the GM was examined within the triceps surea complex because the laser speckle monitoring precluded the use of our custom-made glass water chamber around the isolated GM. Laser speckle images of both GMs were obtained at baseline, ischemia, and reperfusion. The blood flow velocities of the I/R muscle were calculated relative to the blood flow velocity of the contralateral muscle and normalized to baseline values.

Experimental protocol

Following 3 min of 1-Hz twitch stimulation, maximal force production by the muscle was determined during a maximum isometric contraction (150 Hz, 150 ms duration). The maximum tetanic force was used as index of the functional viability of the muscle. Subsequently, following 3 min of no-pacing, the muscle was continuously activated at 1-Hz during 5 min baseline, 60 min ischemia, and 90 min reperfusion. At the end of this protocol, another maximum isometric tetanic contraction was performed. All force signals of the muscle were digitized (1,000 Hz) and analyzed for peak force.

Post-experimental analysis

Immediately after the last contraction, the I/R and contralateral GM muscles were excised, weighted, and separately homogenized in 0.4 ml ice-cold homogenization medium containing (millimolar): 250 sucrose, 20 Hepes (pH 7.4), 10 KCl, 1.5 MgCl2, EDTA, 0.1 PMSF, 5 μg/ml leupeptin and aprotinin, and 1 μg/ml pepstatin. The homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000g for 10 min. The pellet contained the crude mitochondrial fraction and the supernatant the cytosolic fraction. Fractions were quickly frozen at −80°C until determination of enzyme activity or protein levels. The mitochondrial fraction of the control, contralateral, GM was used to obtain an estimate of the amount of HK bound to the mitochondria at the end of reperfusion. The mitochondrial fraction was resuspended in homogenization buffer and incubated for 5 min with 0.5% Triton X-100 and 0.9 M KCl to maximally solubilize hexokinase [16] and centrifuged for 1 min at 10,000g. The resultant supernatant was used for determination of mitoHK activity, measured spectrophotometrically at 25°C with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (from Leuconostoc mesenteroides), glucose, ATP, and NAD+, in the presence of rotenone (1 μM) to inhibit the mitochondrial respiration chain. The cytosolic fraction was used for determination of LDH, measured spectrophotometrically at 25°C with pyruvate and NADH. Cell survival was defined as the amount of LDH activity (unit per milligram protein) remaining in the I/R muscle, relative to the amount present in the contralateral GM. Protein content of the different fractions was determined by the Bradford method.

In order to verify mitochondrial enrichment of the 10,000 g pellet, the mitochondrial marker protein VDAC (anti-VDAC, Calbiochem) was determined in the 10,000 g pellet and supernatant fractions using standard Western blotting techniques (n = 2).

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means ± SE. ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc tests was used to compare group means within one gender. Significance was established at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

The average age of the animals was 18.2 ± 0.3 weeks and was not different between the groups. The overexpressed male and female mice had significantly lower muscle (p = 0.034 and p = 0.002, for male and female mice, respectively) and body weights (p = 0.027 and p = 0.006, for male and female mice, respectively), whereas muscle mass relative to body weight was not different (Table 1). Thus, overexpressing HKII unexpectedly retards growth of skeletal muscle and body weight. However, force producing capacity, expressed per muscle weight, is not affected by overexpressing HKII. Conversely, decreasing HKII in skeletal muscle of male, but not female mice, significantly (p = 0.050) decreased twitch force, with a trend (p = 0.07) towards decreased tetanic force production as well.

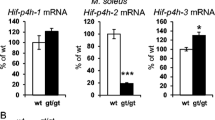

The 10,000 g pellet can be considered as the crude mitochondrial fraction, as indicated by the enrichment of VDAC in this fraction (Fig. 1a). The amount of mitochondrial hexokinase activity in the mitochondrial fraction is given in Fig. 1b. The partial knockout for HKII resulted in 44% and 47% reduction in HK activity relative to wild-type animals, for male and female mice, respectively. Interestingly, the mitochondrial fraction of the GM of female animals contained approximately 20–30% less HK than that for the male mice, for both the wild-type (p = 0.073) and knockout (p = 0.047) animals. Overexpressing HKII resulted in a robust increase in HK activity (360% for male and 480% for female).

a Western blot showing mitochondrial enrichment of the 10,000 g pellet (pel) as compared with the 10,000 g supernatant (sup) fraction using VDAC (∼32 kDa) as mitochondrial marker; the first lane of the blot represents the molecular ladder. b Hexokinase activity in the mitochondrial fraction of the contralateral gastrocnemius medialis muscle of the hexokinase-knockout (HK+/-), wild-type (WT), and hexokinase-overexpressed (HKtg) male and female animals. Values are given as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 versus WT of similar gender

Relative blood flow velocity images of the GM of both hindlegs during baseline, ischemia, and reperfusion are given in Fig. 2. The images (Fig. 2a) clearly illustrate severe ischemia of the left GM during ligation of the femoral artery, followed by successful restoration of perfusion at release of the ligature, whereas perfusion of the contralateral GM was unaffected. The normalized blood flow velocities of all three animals (Fig. 2b) demonstrate consistency of the degree of ischemia during the 60 min ischemic period. Reactive hyperemia during the initial period of reperfusion was observed upon release of the ligature, with normalization of perfusion to baseline conditions at 10 min reperfusion. Thus, the ligation of femoral artery femoralis in this model resulted in severe ischemia and successful reperfusion of the GM muscle in vivo.

Perfusion monitoring of the GM by laser speckle imaging. a Representative baseline, ischemia, and reperfusion laser speckle images of both hindlegs. The white oval indicates the position of the GM. Level of perfusion is scaled from blue (low perfusion) to yellow (medium perfusion) and finally to red (high perfusion); b Normalized blood flow velocities, relative to baseline values, of the GM muscle subjected to ischemia–reperfusion by ligation and release of the artery femoralis. B baseline, I ischemia at 1 (01), 30 (30), and 60 min (60), R reperfusion at 1 (01), 2 (02), 5 (05), and 10 min (10). Values are given as mean ± SEM

The time course of twitch force (normalized to 100% at start ischemia) is presented in Fig. 3. Twitch force production falls sharply upon the induction of ischemia, with less than 20% force after 10 min of ischemia, indicating efficacy of artery femoralis ligation for the GM. At 60 min of ischemia, force production was undetectable for almost all muscles, independent of gender and amount of HK activity present. Following reperfusion, most muscles initiated force production again, indicating reperfusion of the muscle. However, twitch force recovery was only marginal and amounted to 10–30% of pre-ischemic values. Twitch force recovery was not significantly different between WT and HK+/- or WT and HKtg for male or female mice, respectively. These findings of functional muscle recovery were confirmed by the force recovery of maximum isometric contractions (Fig. 4). Tetanic force recovery was 34 ± 12% for male WT muscle and 19 ± 7% for female WT muscle and was not significantly affected by the degree of HKII expression in the muscle.

Twitch force production of the GM during baseline, ischemia (dark bar) and reperfusion for the HK+/-, wild-type (WT), and hexokinase-overexpressed (HKtg) male (Fig. 3a) and female (Fig. 3b) animals. Twitch force is normalized to values measured at end of baseline (t = 0 min). Values are given as mean ± SEM

Finally, we examined whether HKII expression affected cell viability following the in vivo twitch-stimulated ischemia–reperfusion intervention. Surprisingly, despite the large impact of the I/R intervention on the functional recovery, cell viability was rather resistant to this acute I/R insult. Both male and female reperfused GM of WT and HKtg animals contained amounts of LDH that were indiscernible from the amounts present in their non-ischemic, contralateral muscle (Fig. 5). However, even in this model of mild irreversible cell damage, decreasing the amount of HKII resulted in a significant (p = 0.014) decrease in cell viability in the reperfused GM muscle of male, but not female, HK+/- animals as compared with the reperfused GM muscle of male WT animals. The data suggest that diminished amount of HKII in skeletal muscle of male, but not female, animals is associated with increased sensitivity towards structural acute I/R injury.

Discussion

The major findings of this study can be summarized as follows: (1) reducing HKII activity is associated with increased sensitivity towards acute, irreversible, I/R injury in male skeletal muscle, (2) HKII is not a determinant of functional recovery following I/R in skeletal muscle, (3) reduced HKII activity results in reduced force production of gastrocnemius medialis muscle in male animals, and (4) HKII effects on I/R injury and force production are gender-dependent.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating that cellular HKII content is a determinant of ischemia–reperfusion injury of muscle in vivo. Many cellular studies have convincingly shown abrogation of cell death induced by an oxidative stimulus (e.g., H2O2) through increasing mitochondrial bound hexokinase [5, 9, 17, 18, 20]. Besides the use of a rather non-physiological toxic stimulus (H2O2), glucose is also usually the sole substrate in such cellular systems, making it very sensitive to manipulations of the enzyme HK that catalyzes the first step in glucose metabolism. These considerations questioned whether results obtained in such a non-physiological model translate to ischemia–reperfusion in the intact animal. The present study demonstrates that HK also imposes protective effects against ischemia–reperfusion in vivo in the male animal, although protection was restricted to cell death and not to functional recovery. This dichotomy in HK protective effects on recovery of cell death or contractile function was also found for different cardioprotective interventions in cardiac ischemia–reperfusion studies [21, 29] and probably reflects the different mechanisms underlying these processes. That HK protects against cell death instigated by ischemia–reperfusion in the male animal, extends our previous findings [10, 30] on the association of increased mitochondrial HK with ischemic preconditioning in the isolated male rat heart towards a more causal role of HK as one of the determinants of reperfusion injury in vivo, at least for the male animal. It is also in support of recent data showing that decreasing the amount of HK bound to mitochondria results in increased cell death in cellular studies. However, it should be noted that, in our study, we cannot distinguish between decreased cytosolic HK or decreased mitochondrial HK because HK is diminished in both cellular compartments in the HK+/- animal. In vivo interventions that specifically target mitochondrial HK will be necessary to further elucidate whether the increased cell death with diminished cellular HK can be completely ascribed to the decrease in mitochondrial HK.

Surprisingly, partial deletion of HKII was associated with decreased force production. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies that have examined effects of HK on skeletal muscle force production. It is possible that the reduced HK resulted in reduced glucose uptake [8] and thus reduced glycolysis during muscle contraction. Inhibition of glycolysis is known to affect Ca2+ homeostasis and consequently force production [14, 28]. Interestingly, it was recently demonstrated that these HK+/- mice also demonstrated a decreased exercise endurance capacity. An association between diminished endurance capacity and decreased force production was recently observed for skeletal muscles with an impaired phosphocreatine–creatine kinase system [15]. Thus, it is conceivable that the diminished force production partly explains the decreased endurance capacity in the HK+/- mice.

In the current model of acute, mild, ischemia–reperfusion injury of skeletal muscle in vivo, male animals were more sensitive to I/R injury than females. Our data supports other research that demonstrated protection against I/R injury in females, probably mediated by estrogen effects on calcium, inflammation, and the activation of survival pathways [19, 26].

For example, it has been shown that estrogen may increase nitric oxide signaling leading to S-nitrosylation of calcium channels, which reduces calcium loading and thereby I/R injury [19]. In addition, both estrogen and progesterone attenuate leukocyte infiltration into exercise-induced injured skeletal muscle [1, 13], possible through antioxidant and/or membrane stabilization properties [25]. Estrogen was also shown to increase expression of the 70-kDa heat shock protein [1], which may also offer protection against I/R interventions. Thus, it seems that female hormones endorse muscle tissue with an increased natural protection against I/R injury, possibly also preventing the HK-deficiency induced injury in the current, mild, skeletal muscle I/R model in the female mice. The present study excludes a role for mitochondrial hexokinase in the gender effect on I/R injury because HK activity in the mitochondrial fraction of the GM was actually lower in female as compared with male mice.

Methodological considerations

In the present study, we make use of the twitch-stimulated ischemia–reperfusion model, reducing experimental ischemic duration from 2–7 h to 40 min and allowing examination of functional performance during and after ischemia [27]. The maintenance of a relatively high ambient temperature (37°C) together with continuous activation of the muscle during ischemia accelerates the deterioration of energy metabolism and makes it comparable to prolonged noncontracting ischemia–reperfusion interventions [27]. That I/R injury was present is demonstrated by the low recovery of force production upon reperfusion (20–40%). However, cell death was minimal as reflected by the non-significant change in LDH present in the reperfused muscle in comparison with the contralateral muscle of the WT. That this was not due to incomplete ischemia or poor reperfusion was demonstrated by the speckle laser imaging experiments on blood flow velocities in the GM, showing large decreases in blood flow velocities during ischemia and complete restoration of blood flow velocities during reperfusion. Thus, despite the previous demonstrated depletion of high-energy-phosphate compounds and sharp deterioration of force production during ischemia and poor force recovery during reperfusion, the I/R insult was still rather mild. Nonetheless, the mild I/R intervention was severe enough to invoke significant cell death in the GM of the HK+/- male.

In conclusion, the data suggest that HKII is a determinant of cell death in the setting of I/R injury of skeletal muscle of male but not female animals, without affecting functional recovery. In addition, diminishing HKII also affects muscle force production in male animals. The concept that the glycolytic enzyme hexokinase may play a role in the development of in vivo I/R injury of male skeletal muscle is intriguing and is worthy of further investigation.

References

Bombardier E, Vigna C, Iqbal S, Tiidus PM, Tupling AR (2009) Effects of ovarian sex hormones and downhill running on fiber-type-specific HSP70 expression of rat soleus. J Appl Physiol 106:2009–2015

Chang PY, Jensen J, Printz RL, Granner DK, Ivy JL, Moller DE (1996) Overexpression of hexokinase II in transgenic mice. Evidence that increased phosphorylation augments glucose uptake. J Biol Chem 271:14834–14839

Chiara F, Castellaro D, Marin O, Petronilli V, Brusilow WS, Juhaszova M, Sollott SJ, Forte M, Bernardi P, Rasola A (2008) Hexokinase II detachment from mitochondria triggers apoptosis through the permeability transition pore independent of voltage-dependent anion channels. PLoS ONE 3:e1852

Choi B, Kang NM, Nelson JS (2004) Laser speckle imaging for monitoring blood flow dynamics in the in vivo rodent dorsal skin fold model. Microvasc Res 68:143–146

Da-Silva WS, Gomez-Puyou A, Gomez-Puyou MT, Moreno-Sanchez R, De Felice FG, De Meis L, Oliveira MF, Galina A (2004) Mitochondrial bound hexokinase activity as a preventive antioxidant defense. J Biol Chem 279:39846–39855

Eerbeek O, Kernell D, Verhey BA (1984) Effects of fast and slow patterns of tonic long-term stimulation on contractile properties of fast muscle in the cat. J Physiol 352:73–90

Forrester KR, Stewart C, Tulip J, Leonard C, Bray RC (2002) Comparison of laser speckle and laser Doppler perfusion imaging: measurement in human skin and rabbit articular tissue. Med Biol Eng Comput 40:687–697

Fueger PT, Shearer J, Krueger TM, Posey KA, Bracy DP, Heikkinen S, Laakso M, Rottmann JN, Wasserman DH (2005) Hexokinase II protein content is a determinant of exercise capacity in the mouse. J Physiol 566:533–541

Gottlob K, Majewski N, Kennedy S, Kandel E, Robey RB, Hay N (2001) Inhibition of early apoptotic events by Akt/PKB is dependent on the first committed step of glycolysis and mitochondrial hexokinase. Genes Dev 15:1406–1418

Gürel E, Smeele KM, Eerbeek O, Koeman A, Demirci C, Hollmann MW, Zuurbier CJ (2009) Ischemic preconditioning affects hexokinase activity and HKII in different subcellular compartments throughout cardiac ischemia–reperfusion. J Appl Physiol 106:1909–1916

Halseth AE, Bracy DP, Wasserman DH (1999) Overexpression of hexokinase II increases insulin- and exercise-stimulated muscle glucose uptake in vivo. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metabol 276:E70–E77

Heikkinen S, Pietila M, Halmekyto M, Suppola S, Pirinen E, Deeb SS, Janne J, Laakso M (1999) Hexokinase II-deficient mice. Prenatal death of homozygotes without disturbances in glucose tolerance in heterozygotes. J Biol Chem 274:22517–22523

Iqbal S, Thomas A, Bunyan K, Tiidus PM (2008) Progesterone and estrogen influence postexercise leukocyte infiltration in overiectomized female rats. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 33:1207–1212

Gesser H (2002) Mechanical performance and glycolytic requirement in trout ventricular muscle. J Exp Zool 293:360–367

Kan HE, Buse-Pot TE, Peco R, Isbrandt D, Heerschap A, De Haan A (2005) Lower force and impaired performance during high-intensity electrical stimulation in skeletal muscle of GAMT-deficient knockout mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 289:C113–C119

Katzen HM, Soderman DD, Wiley CE (1970) Multiple forms of hexokinase. Activities associated with subcellular particulate and soluble fractions of normal and streptozotocin diabetic rat tissues. J Biol Chem 245:4081–4096

Majewski N, Nogueira V, Robey RR, Hay N (2004) Akt inhibits apoptosis downstream of BID cleavage via a glucose-dependent mechanism involving mitochondrial hexokinases. Mol Cell Biol 24:730–740

Miyamoto S, Murphy AN, Brown JH (2008) Akt mediates mitochondrial protection in cardiomyocytes through phosphorylation of mitochondrial hexokinase-II. Cell Death Diff 15:521–529

Murphy E, Steenbergen C (2007) Gender differences in mechanisms of protection in myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res 75:478–486

Pastorino JG, Hoek JB, Shulga N (2005) Activation of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta disrupts the binding of hexokinase II to mitochondria by phosphorylating voltage-dependent anion channel and potentiates chemotherapy-induced cytotoxity. Cancer Res 65:10545–10554

Peart J, Headrick JP (2003) Adenosine-mediated early preconditioning in mouse: protective signalling and concentration dependent effects. Cardiovasc Res 58:589–601

Pedersen PL, Mathupala S, Rempel A, Geschwind JF, Ko YH (2002) Mitochondrial bound type II hexokinase: a key player in the growth and survival of many cancers and an ideal prospect for therapeutic intervention. Biochim Biophys Acta 1555:14–20

Robey RB, Hay N (2005) Mitochondrial hexokinases: guardians of the mitochondria. Cell Cycle 4:654–658

Sun L, Shukair S, Naik TJ, Moazed F, Ardehali H (2008) Glucose phosphorylation and mitochondrial binding are required for the protective effects of hexokinase I and II. Mol Cell Biol 28:1007–1017

Tiidus PM (2003) Influence of estrogen on skeletal muscle damage, inflammation, and repair. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 31:40–44

Tiidus PM, Enns DL, Hubal MJ, Clarkson PM (2009) Point:counterpoint: estrogen and sex do/not influence post-exercise indices of muscle damage, inflammation and repair. J Appl Physiol 106:1010–1012

Welsh DG, Lindinger MI (1993) Energy metabolism and adenine nucleotide degradation in twitch-stimulated rat hindlimb during ischemia–reperfusion. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metabol 264:E655–E661

Xu KY, Zweiere JL, Becker LC (1995) Functional coupling between glycolysis and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transport. Circ Res 77:88–97

Zuurbier CJ, Eerbeek O, Goedhart PT, Struys EA, Verhoeven NM, Jakobs C, Ince C (2004) Inhibition of the pentose phosphate pathway decreases ischemia–reperfusion-induced creatine kinase release in the heart. Cardiovasc Res 62:145–153

Zuurbier CJ, Eerbeek O, Meijer AJ (2005) Ischemic preconditioning, insulin, and morphine all cause hexokinase redistribution. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289:H496–H499

Zuurbier CJ, Emons VM, Ince C (2002) Hemodynamics of anesthetized ventilated mouse models: aspects of anesthetics, fluid support, and strain. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282:H2099–H2105

Zuurbier CH, Huijing PA (1991) Influence of muscle shortening on the geometry of gastrocnemius medialis muscle of the rat. Acta Anat 140:297–303

Zuurbier CJ, Keijzers PJM, Koeman A, van Wezel HB, Hollmann MW (2008) Anesthesia effects on plasma glucose and insulin and cardiac hexokinase at similar hemodynamics and without major surgical stress in the fed rat. Anesth Analg 106:135–142

Zuurbier CJ, Smeele KMA, Eerbeek O (2009) Mitochondrial hexokinase and cardioprotection of the intact heart. J Bioenerg Biomembr 41:181–185

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Kirsten M. Smeele and Otto Eerbeek contributed equally to the work.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Smeele, K.M., Eerbeek, O., Koeman, A. et al. Partial hexokinase II knockout results in acute ischemia–reperfusion damage in skeletal muscle of male, but not female, mice. Pflugers Arch - Eur J Physiol 459, 705–712 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00424-010-0787-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00424-010-0787-3