Abstract

Background

The large potential of the soil organic carbon (SOC) pool to sequester CO2 from the atmosphere could greatly ameliorate the effect of future climate change. However, the quantity of carbon stored in terrestrial soils largely depends upon the magnitude of SOC mineralization. SOC mineralization constitutes an important part of the carbon cycle, and is driven by many biophysical variables, such as temperature and moisture.

Methods

Soil samples of a pine forest, an oak forest, and a pine and oak mixed forest were incubated for 387 days under conditions with six temperature settings (5 °C, 10 °C, 15 °C, 20 °C, 25 °C, 30 °C) and three levels of soil moisture content (SMC, 30%, 60%, 90%). The instantaneous rate of mineralized SOC was periodically and automatically measured using a Li-Cor CO2 analyzer. Based on the measured amount of mineralized SOC, carbon fractions were estimated separately via first-order kinetic one- and two-compartment models.

Results

During the 387 day incubation experiment, accumulative mineralized carbon ranged from 22.89 mg carbon (C) ·g− 1 SOC at 30 °C and 30% SMC for the mixed forest to 109.20 mg C·g− 1 SOC at 15 °C and 90% SMC for the oak forest. Mineralized recalcitrant carbon varied from 18.48 mg C·g− 1 SOC at 30 °C and 30% SMC for the mixed forest to 104.98 mg C·g− 1 SOC at 15 °C and 90% SMC for the oak forest, and contributed at least 80% to total mineralized carbon.

Conclusions

Based on the results of this experiment, the soil organic matter of the pure broadleaved forest is more vulnerable to soil microbial degradation in northern China; most of the amount of the mineralized SOC derived from the recalcitrant carbon pool. Labile carbon fraction constitutes on average 0.4% of SOC across the three forest types and was rapidly digested by soil microbes in the early incubation stage. SOC mineralization markedly increased with soil moisture content, and correlated parabolically to temperature with the highest value at 15 °C. No significant interaction was detected among these variables in the present study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The magnitude of soil organic matter (SOM) mineralization largely depends on its complex composition and its interaction with different biotic and abiotic variables. SOM is biophysically degraded to various biochemical products, e.g. low molecular weight compounds (monosaccharide, cellulose, glucose, etc.), high molecular weight matter (humus, lignin, etc.), or aliphatic or aromatic materials (fatty acid, ester, waxy, alkene, etc.) (von Lützow et al. 2007). These biodegradation products subsequently interact with mineral soil particles, or may be protected by the microenvironment of the mineral soil, and turn to become an organo-mineral matrix (Rasmussen et al. 2006). Based on its decomposability and availability to soil microorganisms, SOC is usually classified into labile and recalcitrant soil carbon. Labile carbon mainly consists of soil microbial biomass carbon, dissolved organic matter, and easily oxidative organic matter, whereas the recalcitrant carbon usually refers to the component of SOM that is resistant to microbial decomposition or protected by mineral soil particles (Fang et al. 2005; von Lützow et al. 2007). Apart from this classification, SOC is also partitioned into dissolved organic carbon (DOC), particulate organic carbon, microbial biomass carbon, oxidative carbon, and hydrolyzable carbon (von Lützow et al. 2007). Although many different methods have been applied to clearly extract different SOC fractions, a deeper understanding is urgently needed to elucidate the kinetic properties of SOC fractions and their roles in controlling the magnitude of SOM mineralization.

The responses of different SOC fractions to environmental factors were simulated extensively based on a conceptual model, as the analysis method of SOC fractionation could not explicitly predict the impact of future climate change on the SOC pool (Kirschbaum 2000, 2006). The quantity and the mean residence time of labile or recalcitrant carbon have been well established under different incubation conditions using a one- or two-compartment model, which is underpinned by the mechanism of the kinetic theory (Riffaldi et al. 1996; Rey and Jarvis 2006). The carbon mineralization could be estimated by these models as a function of time and temperature, both of which are the most important factors driving SOC mineralization. In contrast to field studies, these conceptual models could provide the least-biased estimates of the correlation between the decomposition of carbon fractions and incubation variables (Kirschbaum 2000), and increase the comparability between different study results. As expected, these conceptual models would help to identify the major contributor to the variations in SOM mineralization processes among the different forest types.

Incubating temperature and moisture are two well-known determinants influencing SOM decomposition. The co-occurrence of high moisture content and high temperature could significantly increase SOM decomposition rate, however only below the threshold value of moisture content does a positive relationship exist between soil CO2 emission and temperature (Howard and Howard 1993). A moisture content between 50 and 60% has been considered optimal for microbial activity (Howard and Howard 1993). Apart from the roles of temperature and soil moisture, the time length of the incubation period is a critical factor in regulating the SOC mineralization process. The proportion of labile and recalcitrant SOC will obviously change with the mineralization process, because there is a large difference in the mean residence time of variant SOC fractions (Mills et al. 2014). The mineralization rate of soil carbon has also been found to decline with the incubation time extending (Reichstein et al. 2000), and the regime function of mineralization variables would substitute each other at different incubation stages (Giardina and Ryan 2000; Rasmussen et al. 2006). Considering the complex properties of different SOC fractions and the uncertainty of their correlation to mineralization variables, the incubation experiment with a longer time period (more than one year) is of vital importance to clarify the mechanisms underlying SOC mineralization of different forest ecosystems.

The forest type will manipulate the quality and quantity of SOM through the above- and belowground litter inputs (Fissore et al. 2008). The first objective of this study was to quantify the pool sizes of labile and recalcitrant SOC and their contribution to the total amount of mineralized SOC for different forest types. Secondly, we aimed to explore the predominant factor controlling the mineralization magnitude of SOC and its fraction. It was hypothesized that the magnitude of SOC mineralization is largely determined by substrate availability in the late incubation stage, and that the incubation factors will affect the supply of SOM to soil microbial decomposers.

Methods

Study site and soil sampling

This study has been carried out in the Taiyueshan Long-Term Forest Ecology Research Station, which is located at the National Forest Park of Lingkongshan (36°33′–36°42′ N, 111°59′–112°07′ E; elevation ranging from 1100 to 1950 m a.s.l.). This forest park is located about 200 km southwest of Taiyuan in the Shanxi Province of northern China. The geographic and meteorological conditions and species composition of the forest communities for this study area had already been introduced in detail by (Zhou et al. 2013). The tree species extensively distributed across this forest park are Pinus tabulaeformis Carrière, Quercus wutaishanica Mayr, Betula dahurica Pall, Betula platyphylla Suk, Juglans mandshurica Maxim, Tilia mongolica Maxim, Populus davidiana Dode, Malus baccata Borkh. The major shrub species are Corylus mandshurica Maxim, Corylus heterophylla Fisch, Acer ginnala Maxim, Lespedeza bicolor Turcz, Philadelphus incanus Koehne, Rosa bella Rehd. The herbaceous community mainly consists of Carex lanceolata Boott, Spodiopogon sibiricus Trin, Rubia chinensis Regel et Maack, Thalictrum petaloideum Linn, Melica pappiana Hempel.

Five forest plots of 20 m × 20 m were established in 2013, for each of three forest types: a Pinus tabulaeformis forest, a Quercus wutaishanica forest, and a mixed forest of P. tabulaeformis and Q. wutaishanica. The plots were laid out along the topography of the Xiaoshegou catchment area, at a distance of 3 km west of the research station. Five soil samples at 20 cm depth were taken using a 4-cm diameter soil auger to assess the soil condition of each forest plot in late August; these samples were then mixed and combined into a single sample after passing through a 2 cm sieve screen to separate rocks and debris. Each composite soil sample was separated into two sub-samples. One sub-sampled was transported in an ice-cooled container to the Key Laboratory for Forest Resources & Ecosystem Processes of the Beijing Forestry University. Soil physicochemical properties were analyzed with air-dried soil of 20 g being ground and passed through a 0.18-mm sieve screen. SOC content was analyzed via the standard Mebius method (Nelson and Sommers 1982). TN content was analyzed following the Kjeldahl digestion procedure and ammonium nitrogen (NH4 - N) was colorimetrically measured by the alkali method with a Tector KJeltec 1025 Distilling system (Gallaher et al. 1976). The soil pH was measured in deionized H2O with a water to soil ratio of 2.5:1 using the Sartorius AG method (PB-10, Sartorius, Germany). The water holding capacity (WHC) was determined by saturating 20 g fresh soil above a filter paper in a 10-cm glass funnel, and then permitting the water to drain for 4–6 h before being weighed (n = 5). The saturated soils were then oven-dried at 105 °C to a constant mass, until the WHC was equal to the percentage of water retained after several hours’ drainage (for 100% WHC). Soil microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen contents were measured using the chloroform-fumigation method with a mean calibration factor kC of 0.38 (Vance et al. 1987a, 1987b). Concurrently with soil sampling, soil bulk density was measured by dividing the mass of oven-dried soil (at 105 °C) by the cylinder volume (100 cm3) after subtracting the detritus volume for each forest plot.

Incubation and measurement of SOC mineralization rate

The second sub-sampled soil was immediately (< 2 d) delivered in a cooler with blue ice to the Key Laboratory of Ecosystem Network Observation and Modeling, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The sub-sampled soil of each forest plot was divided into eighteen 40 g equivalent aliquots; the soil moisture content (SMC) of every six aliquots was individually adjusted to 30, 60 and 90% WHC. The moisture-adjusted soil samples were placed in 200 cm3 plastic flasks with lids perforated to allow gas diffusion, and connected directly to the CO2 measurement system. After getting static and equilibrated for 5 days, six soil samples separately at 30, 60 and 90% of WHC for each forest plot were respectively incubated for 387 days in a microcosm with temperatures of 5 °C, 10 °C, 15 °C, 20 °C, 25 °C and 30 °C and a stable air moisture content (n = 5 per incubator). To prevent anaerobiosis, the perforated hole of the flask lid was not sealed until 24 h before the measurement of soil organic carbon mineralization rate. Throughout the whole incubation period, the flask was periodically weighed and the required proportion of deionized water was added to maintain soil moisture content at 30%, or 60%, or 90% of WHC.

The measurement of SOC mineralization started at different time intervals after the equilibrated soil samples had been incubated in microcosms. The instantaneous rate of SOC mineralization was measured as CO2 efflux from soil within flask on day 1, 3, 5, 8, 16, 23, 29, 36, 43, 57, 75, 118, 151, 180, 225, 252, 293, 361, 387 in sequence. Sixteen flasks of soil samples were placed in an electronic water bath at the same temperature as that at which the soil samples were incubated. These flasks were connected to a PRI-8800 Automatic Temperature Control Soil Flux System (PRI-8800; Pre-Eco, Beijing, China). This automated system was mainly composed of a Li-Cor CO2 analyzer (Li-7000), an air-flow controller, soda-lime equipment to manipulate the initial CO2 concentration, and a data collector. Comprehensive information and the schematic configuration of this automated system were introduced in detail by He et al. (2013). The SOC mineralization rate was estimated using the following equation:

where R s represents the instantaneous rate of SOC mineralization (μg C∙g− 1 soil∙h− 1); L refers to the slope of the CO2 concentration; V is the volume of the incubation flask and gas tube (cm3); m is the dry weight of the soil sample (g); α is the transformation parameter of the CO2 mass; β is the transformation coefficient of time.

Based on the SOC mineralization rate, the cumulative mineralized SOC for a specific period of time was also calculated following the empirical function below.

where C cum C cum is the cumulative mineralized SOC (mg C∙g− 1 SOC); SOC f SOC f refers to soil organic carbon content (g∙kg− 1) for the corresponding forest plot; R si and Rs(i + 1) are the instantaneous rates of SOC mineralization measured consecutively at time i and i + 1, as calculated by Eq. (1).

Calculation of soil carbon fractions

Different soil carbon pools were estimated by the first-order kinetic one-compartment and two-compartment models based on the relationship of cumulative mineralized SOC and the time length of the incubation period. Firstly, the potentially mineralizable carbon pool in soil was calculated via fitting the mean cumulative mineralized carbon data at a different incubation temperature and moisture for each forest type to the following model (Sanford and Smith 1972; Rey and Jarvis 2006):

where C cum (t) is the mean cumulative mineralized SOC until time t (mg C∙g− 1 SOC), C0 is the ‘potential’ mineralizable C (mg C∙g− 1 SOC), k0 is the decomposition rate constant for mineralization carbon (day− 1), and t is the incubation time (day).

Secondly, the first-order two-compartment model was applied to calculate labile carbon fraction and recalcitrant carbon fraction (Andrén and Paustian 1987; Rey and Jarvis 2006). This equation was displayed as below:

where C cum (t) is the mean cumulative carbon mineralized during the incubation period time t (mg C∙g− 1 SOC), C1 is the labile carbon fraction (mg C∙g− 1 SOC), C2 is the recalcitrant carbon fraction (mg C∙g− 1 SOC), k1 and k2 are the first-order kinetic decomposition rate constants for the labile and recalcitrant carbon fractions (day− 1) respectively. The cumulative mineralized SOC (the emitted CO2) is expressed on a basis of SOC content (mg C∙g− 1 SOC) when fitting models (3) and (4) to the incubation data, and the modeled result essentially represents the SOC fraction that was mineralized. More detailed information about the law to employ these models may be found in Rasmussen et al. (2006) and Rey and Jarvis (2006).

In order to get the reasonable parameters from functions (3) and (4), several criteria were set up: that (i) k0 and k1 were larger than 0, and that (ii) k1 was larger than k2, and that (iii) C0, C1 and C2 were larger than zero. Additionally, one assumption was followed that (C1 + C2) was equal to 1000 mg C∙g− 1 SOC (i.e. the two carbon fractions add up to the total amount of initial organic carbon in the sample). Based on the functions (2), (3) and (4) and the estimations of different carbon pools, the quantity of mineralized recalcitrant carbon was assumed to be the difference between the total amount of mineralized carbon and that of C0 (potential mineralizable C) or C1 (labile carbon fraction). In the present study, C0 was used to estimate the amount of mineralized recalcitrant carbon, as most C1 could not meet the criterion (iii) at a moisture content of 30% for all forest types (Additional file 1).

Statistical analyses

The data presented in the tables and figures represent the mean value under different incubation conditions for each forest type. The differences of soil carbon pools for various incubation conditions and forest types were tested using one way ANOVA or multi-factor analysis of variance. Equations (3) and (4) were fitted using non-linear regression analysis (‘nls’ of R language). The starting value for each parameter was obtained from the published literature. Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) was applied using the function ‘cca’ in the vegan package of R. All of the statistical analyses were done using the software R3.4.0. The figures in this paper were compiled using SigmaPlot 10.0 and R software.

Results

Cumulative mineralized carbon

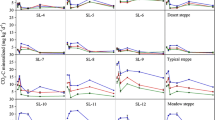

The cumulative carbon mineralized (C cum , C respired per g initial SOC) over the incubation period (387 days) significantly varied with forest type, incubation temperature and soil moisture content, but no significant interaction effect was found on C cum among these three variables (Table 1). Under the same incubation temperature, C cum showed an increasing trend with SMC from 30 to 60 to 90% for each forest type; the forest of Q. wutaishanica had a higher C cum value than those of the P. tabulaeformis forest and the mixed forest, under similar incubation conditions except at 5 °C; a parabolic correlation existed between C cum and incubation temperature at the same SMC gradient for each forest type. The highest value of C cum was 96.74, 109.20, and 100.08 mg C∙g− 1 SOC respectively for the P. tabulaeformis forest, the Q. wutaishanica forest, and the mixed forest under an incubation condition of 15 °C and 90% SMC (Fig. 1; Additional file 2).

Potential mineralizable carbon

Potential mineralizable carbon (C0) was calculated by fitting the first-order kinetic one-compartment model to the data of C cum . The estimation of C0 was lowest at 3.70 mg C∙g− 1 SOC at 10 °C and 30% SMC, and highest at 4.51 mg C∙g− 1 SOC under 15 °C and 90% SMC for the P. tabulaeformis forest, it varied from 3.60 mg C∙g− 1 SOC (20 °C + 30% SMC) to 4.24 (25 °C + 90% SMC) mg C∙g− 1 SOC for the Q. wutaishanica forest, and ranged from 3.59 mg C∙g− 1 SOC (30 °C + 60% SMC) to 4.75 (5 °C + 30% SMC) mg C∙g− 1 SOC for the mixed forest (Table 2). Although the results of multi-factor analysis of variance indicated that C0 and its decomposition rate constant (k0) were markedly influenced by forest type, incubation temperature and SMC, there was not a clear trend of C0 changing with increasing temperature. SMC had a weak positive effect on C0 (Table 3).

The decomposition rate constant (k0) was prominently affected and significantly increased by SMC under the same temperature gradient, and kept increasing slightly with temperature under the same SMC for each forest type. Obviously, k0 under 30 °C and 90% SMC condition was highest at 25.06 × 10− 3, 33.93 × 10− 3 and 32.04 × 10− 3 day− 1 for the P. tabulaeformis forest, the Q. wutaishanica forest, and the mixed forest, respectively (Table 4).

We only presented the data of C1, k1 and k2 at 60%, 90% SMC as supportive materials, since the first-order kinetic two-compartment model did not fit well the data of C cum at 30% SMC for all forest types. C1 was on average lower than C0 by one unit.

Contribution of recalcitrant carbon to the cumulative mineralized carbon

The amount of recalcitrant carbon mineralized during the incubation period was indirectly calculated from the cumulative mineralized carbon (C cum ) minus the potential mineralizable carbon (C0). The value of mineralized recalcitrant carbon varied from 18.48 mg C∙g− 1 SOC at 30 °C and 30% SMC for the mixed forest to 104.98 mg C∙g− 1 SOC at 15 °C and 90% SMC for the oak forest (Table 5). Similar to C cum and C0, the mineralized recalcitrant carbon was also greatly influenced by forest type, incubation temperature and SMC (Table 6).

The mineralized recalcitrant carbon took over more than 80% of cumulative mineralized carbon for all forest types, under any incubation condition. This percentage was significantly manipulated and markedly increased by SMC for each forest type and temperature gradient (Table 7).

Soil biophysical properties and their effects on carbon mineralization

Soil resource content and physicochemical properties were influenced by forest type: the Q. wutaishanica forest had higher values than the P. tabulaeformis forest in SOC, TN, but was lower in SBD (Table 8).

The results of the canonical correspondence analysis indicated that the recalcitrant carbon mineralization was affected jointly by forest type, SOC, SBD, SMBN and soil pH, and its 68.33% variance was mainly ascribed to these five factors (P = 0.003). SOC and SBD had a converse effect and clustered along the first axis explaining 50.42% of the total variance, and SMBN and pH along the second axis comprising 20.02% of the total variance. SBD played an important role in determining the recalcitrant carbon mineralization in the P. tabulaeformis forest, SOC and pH were important factors in the Q. wutaishanica forest, and SMBN and pH had a great function in the mixed forest (Fig. 2).

Discussion

The magnitude of SOC mineralization and its fraction

Although invariant correlations were not detected between the amount of mineralized SOC and some incubation variables, there existed a constant and gradually increasing trend of cumulative mineralized SOC with incubation time in the present study. The longer the incubation time period, the larger the amount of mineralized SOC. At the end of this incubation experiment, the broadleaved forest at 15 °C and 90% SMC was found to have the highest value of mineralized SOC at 109.20 mg C∙g− 1 SOC, which was about four times higher than the lowest value of the mixed forest soil at 30 °C and 30% SMC. The total amount of the mineralized SOC in the present study averaged 58.37 mg C∙g− 1 SOC across all incubation conditions, which was in agreement with other results of Rey et al. (2005, 2008) and of the permafrost peatland in northeast China (Wang et al. 2010). This mean value of total mineralized SOC also fell well within the range of mineralized carbon compiled by Hamdi et al. (2013). The results of the present study agree with other research results where SOC had been mineralized under similar incubation conditions.

The cumulative mineralized carbon had a curvilinear relationship with the incubation time, and was fitted to the first order kinetic one-compartment or two-compartment model to estimate the soil carbon fractions for each forest type. Only the estimates from the one-compartment model were presented in this study, as the two-compartment model did not fit well the data of cumulative carbon mineralized at 30% SMC. The potential mineralizable carbon (C0) averaged 4.00 mg C∙g− 1 SOC, contributing on average 8.36% to the total mineralized carbon across all incubation conditions, and taking over 0.4% of soil carbon. Its decomposition constants (k0) varied around 1.23 × 10− 2 day− 1 for all incubation conditions. As recalcitrant carbon was assumed to be SOC or cumulative mineralized carbon minus potential mineralizable carbon, it contributed more than 90% to the SOC pool and almost 99% to the total mineralized carbon. The lowest proportion of labile SOC was also found by the studies of Yang et al. (2006), Rey and Jarvis (2006), but k0 was slightly lower in the report of Rey and Jarvis (2006). This variation in k0 value may be ascribed to the different moisture content during the incubation process.

The effects of temperature and moisture on SOC mineralization rate

Temperature and moisture content are two important variables manipulating the magnitude of SOC mineralization. When other factors, e.g. soil moisture and pH, are in optimal status, carbon mineralization often exponentially increases with temperature, and their correlation is frequently described by the Arrhenius function or the Michaelis-Menten model (Davidson et al. 2012). In this study, the cumulative mineralized carbon was significantly influenced by the incubation temperature, however, it reached the highest value at 15 °C under each moisture gradient for all forest types. In most cases, no significant difference was found in the total amount of mineralized carbon between 30 °C and 5 °C, except at 30 and 90% SMC for the P. tabulaeformis forest and at 30% SMC for the mixed forest.

The above discrepancy between the changing trend of cumulative mineralized carbon and incubation temperature was mainly attributed to the complexity of soil carbon fraction. In the present study, the labile carbon (C0 or C1) constituted a small amount of the SOC pool, and the larger proportion of mineralized carbon mainly derived from the recalcitrant carbon pool. The carbon pool mineralized during the first 60 days of the incubation period equaled the estimated labile carbon pool, and the instantaneous mineralization rate positively increased with temperature during this first incubation stage (≥ 70 days), and then the mineralization rate began decreasing and was lowest at 30 °C as the incubation time was longer than 70 days. The lower amount of cumulative mineralized carbon at 30 °C may be accounted for by the faster depletion of labile carbon during the prior incubation stage and the difficult availability of recalcitrant carbon at the late incubation stage. The reason for carbon mineralization keeping a higher value at 15 °C was mainly because the mean annual temperature fluctuates around 15 °C in this study area, and because microbial organisms will maintain a higher activity for a longer period at this temperature gradient.

The soil moisture content significantly increased carbon mineralization in the present incubation experiment. Unlike the effect of temperature, the highest moisture content, i.e. 90% SMC, led to the largest amount of cumulative mineralized carbon for all forest types. Soil moisture not only ameliorated the dormant status of microbes, but also increased the dissolution of organic or mineral resources, which in turn supplied a large quantity of substrate to microbial decomposition (Rey et al. 2005; Demoling et al. 2007). Although 60% SMC was suggested to be optimal for microbial activity (Howard and Howard 1993), the higher proportion of sandy particulate modified the aeration of incubating soil samples (Rasmussen et al. 2006), but still promoted the SOC mineralization at 90% SMC.

The effects of forest type and soil properties on SOC mineralization

Forest type is a great biotic manipulator in regulating the turnover of soil organic matter via the quantity and quality of litter input or through the modification of soil biophysical properties. Cellulose and lignin constitute the largest composition of forest ecosystem production, and are the primary determinants of SOM quality and microbial decomposition (Rasmussen et al. 2006; Rey et al. 2008). Generally, the broadleaf forest has a litter production of high quality and quantity, which enhances soil physicochemical properties. In our study, the Q. wutaishanica forest had a higher SOC ant TN content and lower soil bulk density than the P. tabulaeformis forest. Using the data of the measured soil characteristics and the cumulative mineralized carbon, the canonical correspondence analysis indicated that carbon mineralization was significantly influenced by SOC, soil pH, soil microbial biomass nitrogen, and soil bulk density. However, soil bulk density had a negative effect on carbon mineralization along the first CCA axis.

The proportion of labile and recalcitrant carbon specifies the quality of SOC, which determines the magnitude of SOC decomposition. The low quality SOC with more recalcitrant carbon needs a longer time to turnover (Leifeld and Führer 2005). Soil bulk density has a negative correlation with soil organic carbon content, and reflects the mineral soil percentage in the soil regime, the higher its value the slower the carbon mineralization. The change of soil microbial biomass nitrogen may represent the transition of microbial community composition and the substrate use strategy. After the depletion of labile carbon during the first weeks, microbial activity turned to be C-constrained (Demoling et al. 2007). The K-strategist bacteria decomposing recalcitrant carbon (Fontaine et al. 2003) or the fungi using N-rich SOM would become predominant in the microbial community during the late stage of the incubation period (Boberg et al. 2010). Soil pH not only modulates the soil micro-environment and microbial community composition (Strickland and Rousk 2010), but also governs the breakdown processes of SOC decomposition (Riffaldi et al. 1996). The soil mineralization process including the adsorption of SOC by colloids and the substitution between different multivalent cations within organo-mineral complexes (Yuan et al. 2000; Rasmussen et al. 2006) is greatly influenced by soil pH, which ultimately controlled the availability of recalcitrant carbon in the late incubation stage of our experiment.

Conclusions

SOC mineralization was significantly influenced by forest type, incubation temperature and soil moisture content, and reached the highest value for the Q. wutaishanica forest under the incubation condition at 15 °C and 90% soil moisture content. The amount of mineralized SOC slightly increased with soil moisture content and had a parabolic correlationship with the incubation temperature. The simulation results of the first-order kinetic two-compartment model indicated that more than 80% of mineralized SOC derived from the recalcitrant pool of soil organic matter for the temperate forests of northern China.

Abbreviations

- C:

-

Carbon

- C 0 :

-

Potential mineralizable carbon

- CCA:

-

Canonical correspondence analysis

- C cum :

-

Cumulative mineralized SOC

- C r :

-

Mineralized recalcitrant carbon

- DOC:

-

Dissolved organic carbon

- SBD:

-

Soil bulk density

- SMBC:

-

Soil microbial biomass carbon content

- SMBN:

-

Soil microbial biomass nitrogen content

- SMC:

-

Soil moisture content

- SOC:

-

Soil organic carbon

- TN:

-

Total nitrogen content

- WHC:

-

Water holding capacity

References

Andrén O, Paustian K (1987) Barley straw decomposition in the field: a comparison of models. Ecology 68:1190–1200

Boberg JB, Finlay RD, Stenlid J, Lindahl BD (2010) Fungal C translocation restricts N-mineralization in heterogeneous environments. Funct Ecol 24:454–459

Davidson EA, Samanta S, Caramori AA, Savage K (2012) The dual Arrhenius and Michaelis-Menten kinetics model for decomposition of soil organic matter at hourly to seasonal time scales. Globe Change Biol 18:371–384

Demoling F, Figueroa D, Bååth E (2007) Comparison of factors limiting bacterial growth in different soils. Soil Biol Biochem 39:2485–2495

Fang C, Smith P, Moncrieff JB, Smith JU (2005) Similar response of labile and resistant soil organic matter pools to changes in temperature. Nature 433:57–59

Fissore C, Giardina CP, Kolka RK, Trettin CC, King GM, Jurgensen MF, Barton CD, Mcdowell SD (2008) Temperature and vegetation effects on soil organic carbon quality along a forested mean annual temperature gradient in North America. Globe Change Biol 14:193–205

Fontaine S, Mariotti A, Abbadie L (2003) The priming effect of organic matter: a question of microbial competition? Soil Biol Biochem 35:837–843

Gallaher RN, Weldon CO, Boswell FC (1976) A semiautomated procedure for total nitrogen in plant and soil samples. Soil Sci Soc Am J 40:887–889

Giardina CP, Ryan MG (2000) Evidence that decomposition rates of organic carbon in mineral soil do not vary with temperature. Nature 404:858–861

Hamdi S, Moyano F, Sall S, Bernoux M, Chevallier T (2013) Synthesis analysis of the temperature sensitivity of soil respiration from laboratory studies in relation to incubation methods and soil conditions. Soil Biol Biochem 58:115–126

He N, Wang R, Gao Y, Dai J, Wen X, Yu G (2013) Changes in the temperature sensitivity of SOM decomposition with grassland succession: implications for soil C sequestration. Ecol Evol 3:5045–5054

Howard DM, Howard PJA (1993) Relationships between CO2 evolution, moisture-content and temperature for a range of soil types. Soil Biol Biochem 25:1537–1546

Kirschbaum MUF (2000) Will changes in soil organic carbon act as a positive or negative feedback on global warming? Biogeochemistry 48:21–51

Kirschbaum MUF (2006) The temperature dependence of organic-matter decomposition – still a topic of debate. Soil Biol Biochem 38:2510–2518

Leifeld J, Führer J (2005) Temperature response of CO2 production from bulk soils and soil fractions is related to soil organic matter quality. Biogeochemistry 75:433–453

Mills RTE, Tipping E, Bryant CL, Emmett BA (2014) Long-term organic carbon turnover rates in natural and semi-natural topsoils. Biogeochemistry 118:257–272

Nelson DW, Sommers LE (1982) Total carbon, organic carbon, and organic matter. In: Page AL, Miller RH, DR K (eds) Methods of soil analysis. American Society of Agronomy and Soil Science Society, Madison, pp 101–129

Rasmussen C, Southard RJ, Horwath WR (2006) Mineral control of organic carbon mineralization in a range of temperate conifer forest soils. Globe Change Biol 12:834–847

Reichstein M, Bednorz F, Broll G, Kätterer T (2000) Temperature dependence of carbon mineralisation: conclusions from a long-term incubation of subalpine soil samples. Soil Biol Biochem 32:947–958

Rey A, Jarvis P (2006) Modelling the effect of temperature on carbon mineralization rates across a network of European forest sites (FORCAST). Globe Change Biol 12:1894–1908

Rey A, Pegoraro E, Jarvis PG (2008) Carbon mineralization rates at different soil depths across a network of European forest sites (FORCAST). Eur J Soil Sci 59:1049–1062

Rey A, Petsikos C, Jarvis PG, Grace J (2005) Effect of temperature and moisture on rates of carbon mineralization in a Mediterranean oak forest soil under controlled and field conditions. Eur J Soil Sci 56:589–599

Riffaldi R, Saviozzi A, Levi-Minzi R (1996) Carbon mineralization kinetics as influenced by soil properties. Biol Fertil Soils 22:293–298

Sanford G, Smith SJ (1972) Nitrogen mineralization potential of soils. Soil Sci Soc Am Pro 36:465–472

Strickland MS, Rousk J (2010) Considering fungal: bacterial dominance in soils – methods, controls, and ecosystem implications. Soil Biol Biochem 42:1385–1395

Vance ED, Brookes PC, Jenkinson DS (1987a) Microbial biomass measurements in forest soils: determination of k C values and tests of hypotheses to explain the failure of the chloroform fumigation-incubation method in acid soils. Soil Biol Biochem 19:689–696

Vance ED, Brookes PC, Jenkinson DS (1987b) An extraction method for measuring soil microbial biomass C. Soil Biol Biochem 19:703–707

von Lützow M, Kögel-Knabner I, Ekschmitt K, Flessa H, Guggenberger G, Matzner E, Marschner B (2007) SOM fractionation methods: relevance to functional pools and to stabilization mechanisms. Soil Biol Biochem 39:2183–2207

Wang X, Li X, Hu Y, Lü J, Sun J, Li Z, He H (2010) Potential carbon mineralization of permafrost peatlands in great Hing’an mountains, China. Wetlands 30:747–756

Yang L, Pan J, Yuan S (2006) Predicting dynamics of soil organic carbon mineralization with a double exponential model in different forest belts of China. J For Res 17:39–43

Yuan G, Theng BKG, Parfitt RL, Percival HJ (2000) Interactions of allophane with humic acid and cations. Eur J Soil Sci 51:35–41

Zhou Z, Guo C, Meng H (2013) Temperature sensitivity and basal rate of soil respiration and their determinants in temperate forests of North China. PLoS One, e81793 8(12). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0091793

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Chao Guo, Meili Xu and Yi Yu for their assistance with field sampling and soil sample analysis, and we are very grateful to Xiangping Wang, Chunyu Zhang and Quansheng Chen for their advice in using R software. Special acknowledgement is extended to the Key Laboratory of Ecosystem Network Observation and Modeling (CAS) for the permit of laboratory incubation of SOC mineralization. We greatly appreciate the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive advice.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No.YX2014-10) and the Normal Sustainability Fund for the Taiyueshan Long-Term Forest Ecology Research Station (2017-LYPT-DW-148).

Availability of data and materials

All raw data are provided in the Additional files.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HZ carried out the field investigations, analyzed the soil samples in the laboratory, and performed the statistical analysis. ZZ designed the experiment and drafted this manuscript. Both authors agreed to this submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Labile carbon pool and decomposition constants estimated by a two-compartment modelunder different incbuation conditions for three forest types. (DOC 54 kb)

Additional file 2:

Raw data for mineralized SOC during a given incubation period under different conditions for three forest types. (DOCX 27 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, H., Zhou, Z. Recalcitrant carbon controls the magnitude of soil organic matter mineralization in temperate forests of northern China. For. Ecosyst. 5, 17 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-018-0137-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-018-0137-z