Abstract

The Martian Moons eXploration (MMX) mission will study the Martian moons Phobos and Deimos, Mars, and their environments. The mission scenario includes both landing on the surface of Phobos to collect samples and deploying a small rover for in situ observations. Engineering safeties and scientific planning for these operations require appropriate evaluations of the surface environment of Phobos. Thus, the mission team organized the Landing Operation Working Team (LOWT) and Surface Science and Geology Sub-Science Team (SSG-SST), whose view of the Phobos environment is summarized in this paper. While orbital and large-scale characteristics of Phobos are relatively well known, characteristics of the surface regolith, including the particle size-distributions, the packing density, and the mechanical properties, are difficult to constrain. Therefore, we developed several types of simulated soil materials (simulant), such as UTPS-TB (University of Tokyo Phobos Simulant, Tagish Lake based), UTPS-IB (Impact-hypothesis based), and UTPS-S (Simpler version) for engineering and scientific evaluation experiments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Phobos and Deimos, the two moons of Mars, are the target bodies of Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA)’s Martian Moons eXploration (MMX) mission, scheduled to be launched in 2024 (Kuramoto et al. 2021). The spacecraft will land on Phobos’ surface and collect samples of the surface soil to bring them back to Earth for detailed analysis in terrestrial laboratories. The spacecraft carries the small detachable-type rover, developed by Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (CNES) and the German Aerospace Center (DLR), which will be deployed on Phobos’ surface to perform scientific observations (Michel et al. 2021).

Previous asteroid sample-return missions, such as Hayabusa, Hayabusa-2, and OSIRIS-REx, did not attempt a landing, while they collected samples of the target bodies using a touch-and-go approach (Bierhaus et al. 2018; Tachibana et al. 2013). Such a sampling method was preferred to minimize spacecraft interaction with the surface both in time and spacecraft surface area, reducing potential risks posed by both the low-gravity and the lack of knowledge in terms of surface response to an external action. The sampling method of MMX will be different from the one used in these past missions because the gravity of Phobos is considerably larger (Phobos’ surface gravity is more than 50 times larger than that of Ryugu), preventing immediate ascent after touching down due to engineering constraints. Instead, the MMX mothership will land on the surface of Phobos for a few hours, and thus, the mission team must design both the landing and sampling devices appropriately to comply with the surface conditions on Phobos. Such a type of landing is a big challenge for the team because this is the first time that a mission plans to land on a small natural satellite, and observations to date provide a very limited knowledge of the surface conditions of Phobos. For example, we need to constrain how the surface reacts to an external action, even though the actual composition and structure of the surface soil is still unknown and competing hypotheses can explain the observational data. Nevertheless, reasonable estimates of the possible range of surface conditions are required in order to design a robust mission within given budget constraints.

The MMX team organized the Landing Operation Working Team (LOWT) and the Surface Science and Geology Sub-Science Team (SSG-SST) for handling issues regarding the surface conditions on the Martian satellites. After years of discussions, we decided to take the following approach for engineering purposes: (1) compiling relatively reliable information regarding the possible environment of the surface of Phobos based primarily on reviews of previous works; (2) developing a conceptual model of the horizontal and vertical structures of the near-surface regolith, and (3) developing simulating materials (simulants) of Phobos for engineering tests to provide insights into the properties and mechanical response of the soil. This paper summarizes our assessment of the surface conditions of Phobos developed by the LOWT and SSG-SST activities, which provided the necessary engineering constraints to design the MMX mission.

Surface environment of Phobos

As a part of the LOWT/SSG-SST activities, we reviewed previous publications discussing the surface of Phobos, Deimos, small bodies, and the Moon to constrain plausible surface conditions of Phobos from known data. Main findings are summarized below.

General characteristics of Phobos

The general characteristics of Phobos have been studied by both terrestrial observations and previous Mars missions. As a result, unlike previous asteroid missions, the MMX spacecraft’s design could start with some well-constrained physical properties, some of which are summarized in Table 1. Further, photomosaics, maps, and numerical shape models have been built by several researchers, leading to the knowledge of the total surface area and the average slope angle of Phobos. Note that comprehensive reviews are also found in other works (Jacobson 2010; Kuzmin et al. 2003; Murchie et al. 1999, 2014; Willner et al. 2010).

Global shape and slopes

The surface slopes and roughness are particularly important for designing a landing mission. Large-scale slopes and roughness are determined primarily by the global shape of the body and by orbital parameters. Like the synchronous rotation of our Moon around the Earth, Phobos revolves synchronically around Mars, where the near side is always facing Mars. Phobos has an equatorial and almost circular orbit around Mars with a period of 7 h and 39 min and an eccentricity of 0.015. Unlike similarly sized asteroids, the orbital dynamics and the gravitational heterogeneity of Phobos are particularly complex due to the irregular shape and the strong tidal forces resulting from the short distance between Mars and Phobos. Importantly, Phobos orbits at an altitude of about 6000 km from the surface of Mars, making it closer to Mars than its Roche limit (i.e., the tidal force would destroy the satellite if it behaved like a fluid).

The total mass of Phobos is insufficient to make it a spherical body. We also do not expect any heat flux driven from the deeper subsurface. However, we note that the plasma and magnetic field perturbations observed by Phobos 2 spacecraft can be interpreted as outgassing from Phobos (Dubinin et al. 1990) whose nature is not ascertained yet because the Mars Global Surveyor (MGS) orbiter and the Hubble Space Telescope did not detect any evidence of such outgassing (Oieroset et al. 2010; Showalter et al. 2006). Phobos’ overall shape is very irregular due to several large craters, which cause significant variations in local slopes. Even with a classically developed numerical shape model, determining the local gravity direction is not simple due to its close proximity to Mars (Ballouz 2019) and its inferred heterogeneity. A large-scale density heterogeneity of Phobos is likely given the libration observations (Le Maistre et al. 2019). Nevertheless, we calculate the gravity field with a constant density value for Phobos’ entire body to evaluate the slope angle’s-frequency distribution. We find that slopes with respect to the local gravity are mostly less tilted than 40 degrees (Scheeres et al. 2019; Wang and Wu 2020; Willner et al. 2014), with plenty of < 10 degrees slope areas (Fig. 1) preferred by a lander and a rover.

The above estimates of the gravity and tilt are based on a shape model, whose averaged facet area is about 104 m2 (Willner et al. 2014). However, the size of the spacecraft is only 14 m across. Thus, in terms of landing hazard evaluation, we need further discussions on the surface roughness at a higher resolution, discussed in an accompanying paper (Takemura et al. 2021).

Composition of the surface of Phobos

The composition of Phobos is not constrained unambiguously. Phobos’ spectral properties have been investigated at both visible-to-near-infrared and mid-infrared wavelengths (Fraeman et al. 2012, 2014; Murchie et al. 1999; Pieters et al. 2014; Rivkin et al. 2002). Phobos is generally spectrally featureless and very dark, sharing essentially the same characteristics as P- and D-type asteroids (Fraeman et al. 2014). In this sense, the low albedo value can be explained by the presence of organic compounds, as found on meteorites like CM2 chondrites. We also note that the overall spectral characteristics of D-type asteroids and the Tagish Lake meteorite are similar in terms of the brightness, the redness, and the overall shape of spectra (Hiroi et al. 2001; Pajola et al. 2013). Thus, Tagish lake and CM2 chondrites could be good compositional analog materials for Phobos.

Estimating the composition of Phobos largely depends on weak characteristic absorptions in observed reflectance spectra. The overall shapes of the reflectance spectrum may also be useful to evaluate the nature of Phobos’ material. We compiled and resampled reflectance spectra of 369 asteroids and 741 meteorites from mostly the RELAB database (Pieters and Hiroi 2004) to perform principal component and cluster analyses using 16 standard schemes to calculate the relative distance of reflectance spectra (Miyamoto et al. 2018). The results indicate (1) the spectral characteristics of both the blue and red units are not that different from each other; (2) their reflectance spectra characteristics are mostly similar to those of Tagish lake and CM2 chondrites; and (3) the reflectance spectra of Phobos are plotted at the edge of the cluster of darker asteroids (Fig. 2).

Correlation-based mutual distances of 556 meteorites, 259 asteroids, and Phobos’s blue and red units visualized by t-SNE approach, which shows the correlations between C-type asteroids and C-type meteorites. Colors represent types of asteroids and meteorites as denoted in the bottom. Inset is the closeup of the upper middle part of the plot, which shows both the red and the blue units of Phobos is best matched with the Tagish Lake meteorite, which is surrounded by the greenish rectangle

We note that the absorption features in 1.65–3.5 µm match quite well to mature lunar soils and heated carbonaceous chondrites (Rivkin et al. 2002). Also, the darkness and the featureless spectra of Phobos could be explained by shock-darkened silicates (Pieters et al. 2008). MGS thermal emission spectrometer (TES) observations of Phobos indicate that the Tagish Lake meteorite may not be the best mid-IR spectral analog for Phobos and the TES spectra are best matched by the silicate transparency feature found for finely grained particulate basalt and other features observed from phyllosilicate components (Glotch et al. 2018). Thus, the results of previous observations can be interpreted differently along with two hypotheses of the formation of Phobos: a captured asteroid and an in situ formation (Usui et al. 2020).

We interpret these results as follows: (a) if Phobos is a gravitationally captured asteroid, the origin of Phobos is basically an asteroid similar to the parent bodies of those meteorites, such as Tagish Lake and CM chondrites; (b) if the giant-impact hypothesis is correct, Phobos is composed of both Mars and impactor fragments, with impactor fragments dominating the spectral characteristics. The latter may be supported by theoretical studies of Phobos and Deimos’ formations, which favor the giant-impact hypothesis, suggesting that about 50% of the materials forming Phobos originate from Mars, although this percentage must be taken with caution as numerical simulations of giant impacts are extremely challenging and still rely on various simplifications (Hyodo et al. 2017).

Behaviors of dust particles

The weak gravitational field of Phobos may enhance perturbations of dust particle trajectories on the surface. Dust particles could be released from the surface due to some reason: i.e., outgassing from subsurface (Hu et al. 2017), impact shaking invoked by impact or gravitational interaction with other celestial bodies (Richardson et al. 2020), cracking due to thermal fatigue (Dombard et al. 2010), or electrostatic repulsing invoked by solar EUV irradiation (Lee 1996).

The asteroid 433 Eros has been precisely observed by NEAR (Veverka et al. 2000). Although the spectral types of Eros and Phobos are different, the heliocentric distance, size, and estimated gravitational acceleration of Eros are similar to that of Phobos. Thus, the observation result on Eros is worth considering as a reference for Phobos.

Veverka et al. (2001) found several craters on the asteroid 433 Eros being filled with dust grains. Colwell et al. (2005) and following studies (e.g., Senshu et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2016) proposed the possibility that the characteristic structure called “pond” is formed by electrostatic dust levitation. Solar EUV irradiation to the bedrock and dust grains charges them up by photoelectron emission. Dust grains can be launched from the surface due to electrostatic repulsion and eventually they settle in a concave structure to form a dust pond (Hargitai and Kereszturi 2015). On the contrary, Hartzell and Scheeres (2011) pointed out that only the electrostatic force by itself is not sufficient to force dust particles detach from the surface against cohesive force. Thus the lateral dust particle transportation might need external trigger such as impact.

The typical size of a “pond” structure on Eros is smaller than 100 m (Robinson et al. 2001) and it is not clear whether or not there are similar structures on Phobos. The MMX mission will allow us to detect their possible presence by providing data on crater floors in the equatorial regions of Phobos, where lateral dust transfer is possible like on Eros.

Dust deposition rate at the surface

Phobos may have experienced accumulations of dust particles over time because of its proximity to Mars. As a result, the surface of Phobos has evolved differently relative to the surface of small bodies and the Moon. Surface irregularities and the dust environment are likely to be totally different from other known bodies and continuous depositions of dust particles may affect the functions of the lander and the rover.

To estimate the current flux of the dust deposition on the very surface of Phobos, we consider ejecta particles produced by micrometeorite impacts. We estimate ejecta velocity from impact cratering scaling laws (Housen and Holsapple 2011), using for projectile’s conditions, a model of impact fluxes and velocities of micrometeoroids. The upper limit of the deposition rate is realized in the case of impacts on sand (gravity regime) while the lower limit is estimated in the case of impacts on rock (strength regime).

We also assume cratering scaling laws both in the gravity regime (for giving the upper limit) and in the strength regime (for giving the lower limit). We then assume that ejected particles are deposited if their ejection velocities are lower than Phobos’ escape velocity. Assuming a wide range of strength values for the materials on Phobos (from 0.01 to 10 MPa), we can calculate the total volume of ejected materials, whose velocity is slower than the escape velocity, for a single impact event.

Micrometeorite flux on the surface of Phobos is estimated to be 10–16 g/cm2/s (Grün et al. 1985; Divine 1993), in agreement with the estimated interplanetary dust flux to Mars (5.2 × 106 kg/year) based on Flynn (1997) and the most recent estimate of both asteroidal and cometary dust fluxes to Mars of 2.96 ± 0.23 × 106 kg/year (Borin et al. 2017). We expect that the impact velocity of micrometeorites on the surface of Phobos can range from 8.5 km to 15 km/s (Divine 1993), which includes the estimated impact velocities of asteroids on Mars of 9.4 km/s (Ivanov 2001). Our calculation then gives statistical estimates of the total deposited ejecta volume from impacts based on the current frequency distributions of micrometeoroids, which results in the averaged dust deposition rate when divided by Phobos’ surface area. Depending on the average impact velocity of micrometeoroids (U), the deposition rates vary from less than 14 µm/year (U = 8.5 km) to 26 µm/year (U = 15 km). We conclude that the dust deposition rates on Phobos are less than ~ 20 µm/year.

The fate of the ejected materials at speeds faster than Phobos’ escape velocity is strongly influenced by the Martian gravity field. Significantly different from other similarly sized asteroids, particles once ejected from Phobos can be captured in orbits around Mars. The escape velocity from the Mars system at the current orbit of Phobos is 3.03 km/s, which is similar to the average orbital velocity of Phobos (2.14 km/s) but significantly faster than the escape velocity from Phobos (4–10 m/s). Thus, most ejected particles are expected to be captured into orbits around Mars and later possibly re-impact Phobos (Ramsley and Head 2013a). The estimated re-impact velocity is significantly slower than the impact velocities from solar system projectiles (Ramsley and Head 2013b), which could form homogenized depositions on the surface because the perturbation by the re-impact would be limited.

Nature of the Phobos regolith

Regolith of small bodies and satellites

The Moon and asteroids’ surfaces are covered by loose deposits of fragmented debris, commonly called regolith (Walsh 2018). Lunar regolith has been studied intensively through Apollo missions. Trenches and core tubes into the regolith reveal that it is stratified with many buried cobbles and boulders. The surface is continuously and extensively impacted by micrometeorites, resulting in the breaking up of soil particles, the melting of some portions of the soil, and the mixing with lithic fragments. The surface materials are subsequently altered and reworked by a combination of chemical and physical processes until they are buried by fresh ejecta or broken up by further impacts. Over billions of years, such processes form the uppermost lunar regolith that consists of loose but somewhat cohesive, gray-colored, very-fine-grained, and mechanically disintegrated materials. The typical grain size of the surface regolith ranges from < 40 μm to > 800 μm with a median of about 70 μm. Individual lunar soil particles are glass-bonded agglutinates or fragments of various rocks and minerals. The chemical composition of the lunar soil ranges from basaltic (mafic) to anorthositic and includes a small (< 2%) meteoritic component (Niihara et al. 2019). Importantly, even though lunar soils’ chemical compositions vary considerably, variations in mechanical properties such as grain size, density, packing, and compressibility appear to be small.

Regolith on asteroids and comets has also been studied by previous missions, and more than 10 bodies have been observed at close distances (Britt et al. 2019; Chapman, 1996; Lauretta et al. 2019; Russell et al. 2012; Watanabe et al. 2019). Based on these proximity observations, we now know that the surface of an asteroid is covered by regolith whose properties can be very different from one object to the next depending on a number of factors including the asteroid’s mineralogy and its gravity field (size). This regolith evolves and transforms over its history as a result of diverse processes, including impact cratering (e.g., Schmedemann et al. 2014), earlier internal aqueous and thermal alterations (e.g., Wilson et al. 1999), mass movements (e.g., Miyamoto et al. 2007), thermal fatigue (e.g., Delbo et al. 2014) and space weathering (e.g., Sasaki et al. 2001). These processes are often driven by the fundamental mineralogical differences between asteroids which range from primtive to igneous materials. These surface processes result in characteristic evolutions of regolith on small bodies, including a certain homogeneity/heterogeneity in material chemistry, mechanical variations, a range of particle sizes from sub-microns to meter-scale, sometimes up to boulder sizes (e.g., Lauretta et al. 2019; Saito et al. 2006; Sugita et al. 2019). The knowledge of regolith properties and processes is essential for science, landing safety, and selecting landing sites (Yano et al. 2006).

Particle size and its vertical structure of Phobos regolith

Unlike the Moon, Phobos’ orbital configuration allows almost all ejecta from Phobos to re-impact on Phobos after orbiting Mars for years (Ramsley and Head 2013a). Repeated ejections and depositions of impact ejecta on Phobos may contribute to forming a geographically isotropic regolith (Ramsley and Head 2013a), which may explain the smooth-looking surface texture in high-resolution images. The particles orbiting Mars may be perturbed by Martian gravity and solar radiation pressure, which can deplete fragments < 300 µm before re-impacting on Phobos. In this case, Phobos’ surface materials may be deficient in fine-particles smaller than 300 µm (Ramsley and Head 2013a).

On the other hand, as observed on the Moon, surface rocks on Phobos may be broken by collisions of repetitious small impact events. The median survival time of rock fragments > 2 m in diameter is estimated to be about 40–80 Ma on the Moon (Basilevsky et al. 2013). Diurnal temperature cycling and associated stress may also contribute to the destruction of rocks (Delbo et al. 2014). Given the differences in the impact environments, the survival times of rock fragments on Phobos are slightly shorter than those on the Moon. In this sense, Phobos’ surface may contain plenty of fine particles as observed on the Moon.

A significant difference in survival times between the leading and trailing hemispheres was theoretically suggested (Basilevsky et al. 2015). Interestingly, such a difference in regolith maturity is not evident in higher-resolution images. This apparent homogeneity may be caused by the limited image resolution, but it could be due to particles’ homogenization by certain horizontal motions of surface particles. Such activities may be caused by periodic variations in dynamic slopes driven by orbital eccentricity (Ballouz et al. 2019) or by about 1-µm-scale dust, which could cover the surface of Phobos (Popel et al. 2019).

Arecibo 2380 MHz radar data indicate that Phobos’ radar albedo can be very low (OC radar albedo, opposite-sense circular polarization to that transmitted, is 0.021 ± 0.006). This implies that the bulk density of the surface can be 1600 ± 300 kg/m3 (Busch et al. 2007), which is smaller than the range of possible bulk densities of Phobos of about 1867–1885 kg/m3 (Willner et al. 2010). This low surface density suggests that the top of the surface can be covered by low bulk-density materials such as accumulated dust or lag, implying a high porosity of the upper layer.

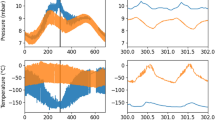

Another useful information to estimate the particle size-distribution is surface thermal inertia, which is estimated to be 40–70 J m−2 K−1 s−1/2 based on Viking observations (Lunine et al. 1982) or 20–40 J m−2 K−1 s−1/2 based on Phobos 2 observations (Kührt et al. 1992); these suggest that the average particle diameter is expected to be < 2 mm in most regions. Assuming a thermal inertia of 55 J m−2 K−1 s−1/2, the most probable particle diameter and porosity values are < 1 mm and > 53%, respectively (Sakatani et al. 2012).

Another approach to understanding regolith properties is to understand the formation of geologic structures on Phobos, namely the systems of grooves that are found, both parallel and criss-crossing networks of linear features that appear to correlate with the increasing tidal strain (Hurford et al. 2016) as Phobos spirals closer to Mars due to tidal friction. It has long been suggested (Yoder et al. 1982) that these features may be granular fissures, and in order to match these features, a low surface cohesion is required. Note that some resemble secondary crater chains.

Accounting for these considerations, we assume for our reference model that the regolith of Phobos holds the characteristics listed in Table 2 and that the surface of the regolith has at least three layers (Fig. 3): (1) a thin, extremely under-dense uppermost layer (< 3 cm in thickness) of micron-scale accumulated dust; (2) a 10-cm- to 3-m-thick regolith layer with particles accumulated at relatively high porosity, and (3) a > 10-m-thick regolith layer with lower porosity.

Development of Phobos simulant

Necessity of simulant

Mechanical properties of the surface soil, such as bearing capacity, bulk frictional coefficient, and other parameters related to granular material behavior, are essential for designing a lander, a rover, and a sampler. However, theoretical estimates of these parameters are generally a challenge due to our limited understanding of granular material’s behavior under a low-gravity environment. For example, the bearing capacity depends on several parameters, including the cohesion, the effective weight of the soil, and the external friction angle, which may significantly vary with depth. Even on Earth, these values are estimated empirically with additional safety factors. Furthermore, fundamental assumptions regarding the soil deformations resulting from local shear failure may have further limitations when applied to the dynamic situation under a low-gravity environment, where the timing of interacting particles and artifacts (such as landing pad and rover wheels) can differ significantly. Thus, answering engineering needs regarding essential parameters for grasping the bulk response of soils to artifacts under the low-gravity environment remains a great challenge.

In the civil engineering field, mechanical properties of soil are experimentally measured before developing mission hardware. However, this is usually very difficult for planetary exploration. Even though NASA’s Stardust and JAXA’s Hayabusa and Hayabusa2 spacecraft successfully returned samples from small bodies, those extra-terrestrial materials are too precious to perform the measurements and experiments necessary for the above purposes. Some fundamental parameters may be evaluated using meteorites, but their availability is also limited. Thus, materials aimed at simulating these solid bodies (simulants) become important substitutes for obtaining reasonable constraints on original material behavior (Britt et al. 2019; Zeng et al. 2019).

Simulants have been used in previous space missions for engineering purposes. For example, the well-known products JSC-1 (Willman et al. 1995), JSC Mars-1 (Allen et al. 1998), and NU-LHT (Stoeser et al. 2008) are used to simulate lunar and Martian surface materials (for more details, see Planetary Simulant Database at the Center for Lunar and Asteroid Surface Science web-page at https://simulantdb.com). Simulants of asteroids are different from those of the Moon and Mars because asteroids have different histories and much lower surface gravities than planetary bodies and the Moon. Moreover, asteroids’ properties are known only for the few asteroids that have been visited by spacecraft, and even for those, the mechanical properties of the regolith are not well understood. Nevertheless, using meteorites as asteroid analogues, well-prepared asteroid simulants have been produced at many different research facilities (Metzger et al. 2019), including the Center for Lunar and Asteroid Surface Science (CLASS) at the University of Central Florida (UCF) (Britt et al. 2019). In fact, developing and measuring the physical properties of simulants has become an essential aspect in the design of new asteroid missions (Zeng et al. 2019) and even for ongoing missions (Miyamoto and Niihara 2020).

Development of Phobos simulants

As we discussed in “Nature of the Phobos regolith”, our partial understanding of the nature of Phobos regolith is insufficient to constrain the mineralogical compositions of Phobos regolith. Even if the chemical and mineralogical compositions were precisely understood, the behavior of the bulk soil could not be fully determined without knowing particle sizes, particle shapes, and their distributions. However, current observations do not allow constraining those parameters. Nevertheless, some combinations of those parameters are not physically possible, so we can at least eliminate such combinations. For example, microscopic porosity and friction angle depend on mineral composition and shape of particles, and thus we can use this dependency to define realistic sets of those parameters. An additional effort needs to be made to limit the parameter space to a range that can be covered by experiments.

Therefore, we decided to take a practical approach to evaluate the bulk behavior of the surface soil and its interactions with a spacecraft/rover. We first developed blocks of simulated materials with appropriate chemical compositions and mineral abundances based on observational constraints, especially on the reflectance spectra. We then modified the particle shapes and size distributions to make the materials match the likely ranges of bulk properties of surface soil, such as the bulk density, the bulk internal friction angle, and the grain sizes, which are weakly constrained from observations.

To cover the two considered scenarios for the origin of Phobos (capture and giant impact) that are still consistent with current observational data (Usui et al. 2020), at least two types of materials needed to be prepared.

Observations by the high-resolution imaging science experiment (HiRISE) and high-resolution stereo camera (HRSC), respectively, onboard Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) and Mars Express, indicate a level of color heterogeneity of the areas in and around Stickney crater. However, the spectral characteristics of these areas are very similar, and thus the mechanical properties of the surface soil may not be that different in these areas (Hemmi and Miyamoto 2020). We also note that the amount of Mars ejecta delivered to Phobos within 500 Myr is estimated to be ~ 1700 ppm in Phobos regolith (Hyodo et al. 2019). This is a significant amount for the MMX science, but still negligible for the surface soil’s bulk material properties.

We conclude that the best choices for simulated materials for engineering purposes are materials whose compositions are similar to either (1) Tagish Lake (carbonaceous chondrite of petrologic type 2 that is ungrouped; C2-ung) and CM2 chondrites for the captured asteroid scenario for the origin of Phobos or (2) mixtures of phyllosilicate and Mars-originated materials such as basalts or dunites for the giant-impact scenario. Therefore, through our interaction with UCF, we developed two types of simulants such as a Tagish Lake-based simulant (UTPS-TB; Univ Tokyo Phobos Simulant, Tagish lake-based) and mixtures of UTPS-TB and mars-like materials as powders of dunite/basalts (UTPS-IB; Univ Tokyo Phobos Simulant, impact hypothesis based). We also developed a simpler version of the simulant (UTPS-S).

UTPS-TB: Univ Tokyo Phobos simulant, Tagish Lake based

UTPS-TB (University of Tokyo Phobos simulant, Tagish Lake based) is a simulant based on the asteroid capture theory. The dark and featureless reflectance spectra of Phobos in the visible and near-infrared wavelengths are interpreted as indicating that the overall constituent materials of Phobos could be analogous to carbonaceous chondrite-like materials. As discussed in Chapter 3, we assume that Tagish Lake meteorite is the best analog material from the similarity in the reflectance spectra to Phobos and we thus aimed at developing materials with a similar mineral abundance.

After the fall of the Tagish Lake meteorite (10 kg) in 2000, numerous mineralogical and cosmochemical works have been performed. This chondrite has a trace amount of chondrules, while the majority (> 60 vol.%) is a fine matrix composed of phyllosilicate material made of Mg-rich phyllosilicates (saponites and serpentine; Mg# = Mg/(Mg + Fe) = ~ 0.80) (Bland et al. 2004; Izawa et al. 2010; Nakamura et al. 2003; Zolensky et al. 2002).

As we discussed above, we decided not to try to develop materials precisely matching the meteorite. We obtained several tons of different types of ore to develop simulants, including dunite from the Hidaka area, powdery magnetite from the Kamaishi area, limestone and dolomite from the Kuzū area, pyrite from the Awashiro area, and asbestos-free serpentinite from the Ube area. Although majority of matrix component of Tagish Lake meteorite is saponite (Zolensky et al. 2002; Nakamura et al. 2003), we used Mg-rich serpentinite because of the easiness of acquisition. Such raw materials are stored at our storage field in the Kakioka campus of the University of Tokyo in Ishioka-shi, Ibaraki prefecture, Japan, where about 460,000 m2 of open space is available.

We, then, crushed Mg-rich phyllosilicates (asbestos-free serpentinite), Mg-rich olivine, magnetite, Fe–Ca–Mg carbonates, and Fe–Ni sulfides into very fine particles by using various crushers depending on the strengths of materials. We darkened the crushed rocks using nano-particle carbon that has a very flat spectrum in the visible range. In fact, carbonaceous chondrites have variations in their color, which result from different abundances of carbon and might affect reflectance characteristics (Kring et al. 1996). Tagish Lake, the darkest among all meteorites, contains more than 3.6 wt.% of carbon with 4% reflectance (Brown et al. 2000) (Figs. 5 and 6). Thus, to simulate this reflectance signature, we mixed nano-particle carbon with polymer organic materials. All the constituents were mixed under wet conditions and then dried completely. The initial liquid content is adjusted to control the compressible strength. The bulk mineral abundances of UTPS-TB and Tagish Lake are summarized in Table 3.

The procedure for the development of the UTPS-TB is as follows:

-

1)

Crushing the serpentinite to sizes under 4 cm at the mining company mostly for the ease of handling.

-

2)

Placing the rocks in the sun to remove water, then drying them in an air-conditioned room.

-

3)

Crushing the rocks to sizes under 100 μm (with a majority under 45 μm), using the cage-mill and roller-mill.

-

4)

Mixing the powdered rocks of different minerals in wet condition.

-

5)

Adding nano-carbon suspension water with organic matter to adjust the color.

-

6)

Baking the mixed materials under 100 °C in an oven to make blocks, each of a mass about ~ 10 kg.

-

7)

Crushing the blocks with hammers and a stamp-mill.

-

8)

Sieving and mixing to adjust the particle size-distributions.

UTPS-IB: Univ Tokyo Phobos simulant, impact-hypothesis based

UTPS-IB (Univ Tokyo Phobos Simulant, Impact-hypothesis Based) is a simulant based on the giant impact theory. We developed this simulant based on the idea that, as a result of the asteroid giant impact on Mars, material from the Martian crust and upper mantle was excavated and distributed in orbit around Mars together with a fraction of the asteroid material, generating a debris disk in which re-assembly occurred, eventually forming Phobos and Deimos. Based on this scenario, Phobos’ constituent materials are likely mixtures of asteroidal materials and debris originated from Martian crust and mantle materials. Following this scenario, we mixed UTPS-TB, dunite, and basalt, which are assumed to represent impactor asteroid material, Martian mantle materials, and Martian crust, respectively.

We mixed basalt and dunite with the weight ratio of 1:1 as Martian crust and upper mantle materials. We then darkened them with nanophase carbon (adjusted for carbon contents of 4% in weight) to simulate the darkening of Phobos by FeS and/or carbon material after it was formed. The simulant is used for spectral measurement to test how it differs from UTPS-TB. We find that carbon and fine particles of sulfide materials (even in low abundance) covering the surface of constituent materials cause dark color and features signature. In summary, the procedure for the development of the UTPS-IB is as follows:

-

1)

Crushing the dunite and basalt rocks to sizes under 4 cm at the mining company mostly for the ease of handling.

-

2)

Placing the rocks in the sun to remove water, then drying them in an air-conditioned room.

-

3)

Crushing the rocks with a jaw crusher.

-

4)

Crushing the blocks of UTPS-IB simulant.

-

5)

Sieving and mixing to adjust the particle size-distributions.

UTPS-S: Univ Tokyo Phobos simulant, simpler version

UTPS-TB and UTPS-IB are designed to be very dark and fragile to simulate the Tagish Lake meteorite. Thus, handling these simulants requires some special care. For example, due to the nature of powdery materials, they can easily absorb water vapor. Also, they can easily fly through the air by wind and stay on the floor. Furthermore, they leave dark stains on hands, containers, and instruments. Therefore, for some conventional engineering tests at an early stage, much more manageable materials are preferred. As our estimates of mechanical properties of Phobos’ soil are still within a large parameter space, materials with properties at some endpoints within the observational constraints are sufficient for mechanical tests, even if their optical characteristics are not necessarily similar to Phobos soils.

We prepared various powdery materials by crushing rocks of serpentinite, dunite, silica sands, pyrites, magnetites, dolomites, calcites, and other phyllosilicates as well as UPTS-TB and -IB for measuring the strength of fine materials. We then selected the materials and determined mixing ratios for our simplified simulants, covering a wide range of mechanical strengths. We baked these materials and UTPS-TB and UTPS-IB under 110 °C in an oven for more than 24 h before roughly estimating each soil’s strength by a penetration test with a sample tube with an outside diameter of 50 mm and an inside diameter of 10 mm (in a way similar to the standard penetration test). We performed the penetration tests at least three times for averaging. Based on these results, we developed UTPS-S (Univ Tokyo Phobos Simulant, Simpler version) to simulate the mechanical behaviors of UTPS-TB and UTPS-IB.

We developed three types of UTPS-S simulants. UTPS-S1 is mostly a powdery material with two types of crushed serpentinite, which is the major constituent of the Tagish Lake meteorite and CM2 chondrites. UTPS-S2 is composed of a 1:1 mixture of both serpentinite and dunite powders of 2–4 mm in diameter. UTPS-S3 is also a 1:1 mixture of both serpentinite and dunite powders of under 4 mm in diameter. Note that UTPS-S is developed for mechanical tests, so the optical characteristics are totally different from (significantly brighter than) UTPS-TB.

Particle size distributions of simulants

Particle size distributions of Phobos’ soil are difficult to constrain from available observations. As discussed in “Particle size and its vertical structure of Phobos regolith”, we assume that the surface soil is composed of three layers, starting from 0 to 3 cm depth of micrometer-sized fluffy dust particles, then high-porosity debris from 10 cm to 3 m depth, and finally more than 10 m of stable regolith. Our focus is in the upper several meters, where the lander and the rover interact with the surface. Thus, we assumed the following conceptual models for the particle size distributions for the upper regolith of Phobos (Figure 4). Our references behind the models 1, 2, and 3 are lunar surface regolith, possible regolith of the smooth area of Itokawa, and those between 1 and 2, respectively.

We use the Japanese standard sieve series with mesh opening of 32, 53, 75, 106, 250, 500, 1000, and 2000 μm to sieve crushed materials. After sieving, we mixed them to adjust the particle size distributions to follow the models 1–3 for UTPS-TB. As for the UTPS-S, we took different particle size-frequency distributions, as discussed above, to simulate the bulk behaviors of UTPS-TB.

Preliminary results of properties of UTPS simulants

The general appearance of the UTPS-TB is very similar to the Tagish Lake meteorite. Figure 5 shows a centimeter-sized block of UTPS-TB in comparison with a Tagish Lake meteorite of similar size.

Optical and backscattered electron images of UTPS-TB (A–C) simulant and Tagish Lake meteorite (D–F). UTPS-TB simulate petrographical signature: phenocrysts of silicate and opaque minerals are embedded in a loosely jammed fine grained (< 20 µm) serpentine matrix. UTPS-TB simulates mineral abundance and visible and near-infrared reflectance of Tagish Lake meteorite

Figure 6 shows the reflectance spectrum of Phobos simulant in the visible-to-near infrared wavelength range to compare with those of Phobos’s blue and red units, and the reflectance spectrum at wavelength from 0.5 to 20 µm to compare with that of the Murchison meteorite. These suggest that the UTPS-TB shares the same optical characteristics as both Phobos and CM2 meteorites as expected. The reflectance spectrum of the UTPS-IB simulant is also similar to that of carbonaceous chondrites and UTPS-TB. Thus, both UTPS-TB and UTPS-IB are reasonable simulants for Phobos’ optical characteristics based on different origin scenarios.

We measured the grain density, the poured bulk density (i.e., the bulk density just poured into a cylinder), and the tapped density (the bulk density after tapped the cylinder) of each simulant. The grain density is measured by the pycnometer method (typically used for non-porous solids) with a pycnometer of 25 ml and an electronic balance with 0.1 mg readability at room temperature. Typical values are summarized in Table 4. The grain density of UTPS-TB measured by the pycnometer method is 2.8–2.9 g/cm3, which is consistent with the Tagish Lake meteorite (grain density of 2.5 ~ 2.9; Hildebrand et al. 2006).

The bulk density of a few cm-sized blocks of UTPS-TB is measured using 65-μm glass beads following the method proposed for meteorites (Consolmagno et al. 2008). We find that the bulk apparent density of the block is 1.68 ± 0.03 g/cm3, which means the micro-porosity of the block is 40.8 ± 1.0% based on the grain density of UTPS-TB (2.84 g/cm3). Figure 5 shows the SEM (backscattered electron) image of Tagish Lake (left) and UT Phobos Simulant (UTPS-TB), whose appearances, including the sizes of matrixes and cracks, are similar. Such similarity may explain the similarities in the bulk density of UTPS-TB and the Tagish Lake meteorites.

Poured bulk densities and tapped densities of various simulants are listed in Table 5. Note that these values are, as expected, lower than the packed bulk density, which may be achieved at deeper parts of Phobos (i.e., at the layer 3 or deeper in Fig. 4). Thus, we assumed that the density of simulants should be lower than the averaged density of Phobos (1.860 ± 0.013 g/cm3).

The angles of repose of simulants are measured by the pouring method with the base acrylic ring of 5 cm in diameter poured from 8 mm diameter funnel for 50 g simulant. The overall shapes of the cone are measured from video images to obtain the averaged value of the angle of repose. Table 5 shows the summary of the measurements. We checked the particle shapes by looking at microscope images of particles. Aspect ratios for 2- to 4-mm sized particles of UTPS-TB and UTPS-S2 are 1.47 ± 0.02 and 1.62 ± 0.02, respectively.

The tensile strength and compressive strength were measured at a loading rate of 0.001 mm/s for a cylinder with a diameter of 20 mm and a height of 6 − 21 mm. The results were 0.222 ± 0.087 MPa and 1.11 ± 0.31 MPa, respectively (Shiomoto et al. 2020). Note that the reported compressible strength of Tagish Lake varies from 0.7 MPa and larger, so we typically arranged the compressible strength to be as large as about 1 MPa (Brown et al. 2000; Tsuchiyama et al. 2009).

Concluding remarks

The design of the rover, the lander (mother spacecraft), and its sampling approach requires the following knowledge of the surface conditions: the thermal inertia, the emissivity, and the albedo of the soil influence the spacecraft thermal conditions. Specifications needed for the navigation of the mothership and the rover include spectral albedo in the visible wavelengths and small-scale topographic irregularities. Those for landing operations and rover operations include the gravity vector, surface accelerations, as well as surface inclinations and local surface roughness. Those for safe and stable landing include dust deposition rate, meteoroid flux, and regolith electrostatic conditions, which are important to evaluate the possible deposition of dust on solar panels. Other important parameters are regolith particle size, density, vertical structure, ground strength parameters (such as cohesion, internal friction angle, bearing capacity), friction between footpad and regolith, ground deformation parameters (Young’s modulus, Poisson’s ratio), as well as terra-mechanical parameters for the mechanical properties of the regolith.

The Landing Operation Working Team (LOWT) and the Surface Science and Geology Sub-Science Team (SSG-SST) are organized for handling scientific and engineering issues regarding the surface conditions and environments of the Martian satellites. Through the LOWT activities, we categorized the related parameters into three groups, such as (1) relatively precisely known parameters, (2) reasonably estimated parameters, and (3) parameters that remain a challenge to be evaluated. Parameters of the group (1) such as the dimension, the mass, and the volume of Phobos, constrain orbital parameters. The group (2) parameters include the local gravity, the local slope angle, the surface temperature, the magnetic field, the chemical variations, the dust deposition rate, and the meteorite flux. The group (3) parameters include regolith’s mechanical properties, such as the vertical structure and particle-size distributions of regolith.

The mechanical properties of regolith, including the coefficient of settlement, bearing capacity, and strength, are essential for designing the landing pad, the sampler, and the rover. However, the expected range of these values is even more difficult to constrain as they also depend on the packing density and particle size distributions that are other big unknowns. To practically evaluate the bulk behavior of the soil against artifacts, we developed three types of Phobos simulants (UTPS-TB, UTPS-IB, and UTPS-S). These are used for engineering tests to provide insights into properties of the soil.

The optical characteristics of each of the simulants are similar to the surface of Phobos. This similarity is useful to simulate small topography of Phobos in the laboratory. Figure 7 shows the simulated surface of Phobos with various size-distributions of UTPS-TB, which we assume to best represent the surface conditions of Phobos. Such a simulated surface was useful for simulating the navigation of spacecraft and scientific evaluations of images in earlier phases of the mission design (Miyamoto and Niihara 2020).

Our work led to the development of more than 1000 kg of simulants, which offer unique opportunities for international collaborators to perform scientific and engineering studies in preparation to and during space missions as well as for data interpretation. The simulants are provided to the MMX engineering team and scientists in Japan and Europe and stored in the storage area for further investigations in the future. Previous missions to asteroids and comets discovered many unexpected facts about the surface conditions of these bodies. When this happens, a simulant of the target body might need to be modified to reflect the new observational data, which occurred during the Hayabusa2 mission.

Availability of data and materials

Some simulant materials may remain in Miyamoto’s lab and available to share for scientific research.

References

Allen CC, Jager KM, Morris RV, Lindstrom DJ, Lindstrom MM, Lockwood JP (1998) JSC Mars-1: a Martian soil simulant. Space 98:469–476

Andert TP, Rosenblatt P, Pätzold M, Häusler B, Dehant V, Tyler GL, Marty JC (2010) Precise mass determination and the nature of Phobos. Geophys Res Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009gl041829

Ballouz RL, Baresi N, Crites ST, Kawakatsu Y, Fujimoto M (2019) Surface refreshing of Martian moon Phobos by orbital eccentricity-driven grain motion. Nat Geosci 12(4):229–234. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-019-0323-9

Basilevsky AT, Head JW, Horz F (2013) Survival times of meter-sized boulders on the surface of the Moon. Planet Space Sci 89:118–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pss.2013.07.011

Basilevsky AT, Head JW, Horz F, Ramsley K (2015) Survival times of meter-sized rock boulders on the surface of airless bodies. Planet Space Sci 117:312–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pss.2015.07.003

Bierhaus EB, Clark BC, Harris JW, Payne KS, Dubisher RD, Wurts DW, Hund RA, Kuhns RM, Linn TM, Wood JL, May AJ, Dworkin JP, Beshore E, Lauretta DS (2018) The OSIRIS-REx spacecraft and the touch-and-go sample acquisition mechanism (TAGSAM). Space Sci Rev. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-018-0521-6

Bland PA, Cressey G, Menzies ON (2004) Modal mineralogy of carbonaceous chondrites by X-ray diffraction and Mössbauer spectroscopy. Meteorit Planet Sci 39(1):3–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1945-5100.2004.tb00046.x

Borin P, Cremonese G, Marzari F, Lucchetti A (2017) Asteroidal and cometary dust flux in the inner solar system. Astron Astrophys. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201730617

Britt DT, Cannon KM, Donaldson Hanna K, Hogancamp J, Poch O, Beck P, Martin D, Escrig J, Bonal L, Metzger PT (2019) Simulated asteroid materials based on carbonaceous chondrite mineralogies. Meteorit Planet Sci 54(9):2067–2082. https://doi.org/10.1111/maps.13345

Brown PG, Hildebrand AR, Zolensky ME, Grady M, Clayton RN, Mayeda TK, Tagliaferri E, Spalding R, MacRae ND, Hoffman EL, Mittlefehldt DW, Wacker JF, Bird JA, Campbell MD, Carpenter R, Gingerich H, Glatiotis M, Greiner E, Mazur MJ, McCausland PJ, Plotkin H, Rubak Mazur T (2000) The fall, recovery, orbit, and composition of the Tagish Lake meteorite: a new type of carbonaceous chondrite. Science 290(5490):320–325. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.290.5490.320

Busch MW, Ostro SJ, Benner LAM, Giorgim JD, Magri C, Howell ES, Nolan MC, Hine AA, Campbell DB, Shapiro II, Chandler JF (2007) Arecibo radar observations of Phobos and Deimos. Icarus 186(2):581–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2006.11.003

Chapman CR (1996) S-type asteroids, ordinary chondrites, and space weathering: the evidence from Galileo’s fly-bys of Gaspra and Ida. Meteorit Planet Sci 31(6):699–725. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1945-5100.1996.tb02107.x

Colwell J, Gulbis A, Horanyi M, Robertson S (2005) Dust transport in photoelectron layers and the formation of dust ponds on Eros. Icarus 175(1):159–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2004.11.001

Consolmagno GJ, Britt DT, Macke RJ (2008) The significance of meteorite density and porosity. Chem Erde-Geochem 68(1):1–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemer.2008.01.003

Delbo M, Libourel G, Wilkerson J, Murdoch N, Michel P, Ramesh KT, Ganino C, Verati C, Marchi S (2014) Thermal fatigue as the origin of regolith on small asteroids. Nature 508(7495):233–236. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13153

Divine N (1993) 5 Populations of interplanetary meteoroids. J Geophys Res-Planet 98(E9):17029–17048. https://doi.org/10.1029/93je01203

Dombard AJ, Barnouin OS, Prockter LM, Thomas PC (2010) Boulders and ponds on the Asteroid 433 Eros. Icarus 210(2):713–721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2010.07.006

Dubinin EM, Lundin R, Pissarenko NF, Barabash SV, Zakharov AV, Koskinen H, Schwingenshuh K, Yeroshenko YG (1990) Indirect evidences for a gas dust torus along the phobos Orbit. Geophys Res Lett 17(6):861–864. https://doi.org/10.1029/GL017i006p00861

Flynn GJ (1997) The contribution by interplanetary dust to noble gases in the atmosphere of Mars. J Geophys Res-Planet 102(E4):9175–9182. https://doi.org/10.1029/96je03883

Fraeman AA, Arvidson RE, Murchie SL, Rivkin A, Bibring JP, Choo TH, Gondet B, Humm D, Kuzmin RO, Manaud N, Zabalueva EV (2012) Analysis of disk-resolved OMEGA and CRISM spectral observations of Phobos and Deimos. J Geophys Res-Planet. https://doi.org/10.1029/2012je004137

Fraeman AA, Murchie SL, Arvidson RE, Clark RN, Morris RV, Rivkin AS, Vilas F (2014) Spectral absorptions on Phobos and Deimos in the visible/near infrared wavelengths and their compositional constraints. Icarus 229:196–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2013.11.021

Glotch TD, Edwards CS, Yesiltas M, Shirley KA, McDougall DS, Kling AM, Bandfield JL, Herd CDK (2018) MGS-TES spectra suggest a basaltic component in the regolith of Phobos. J Geophys Res-Planet 123(10):2467–2484. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018je005647

Grün E, Zook HA, Fechtig H, Giese RH (1985) Collisional balance of the meteoritic complex. Icarus 62(2):244–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/0019-1035(85)90121-6

Hargitai H, Kereszturi A (2015) Encyclopedia of planetary landforms, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-1-4614-3133-6, 2497pp

Hartzell CM, Scheeres DJ (2011) The role of cohesive forces in particle launching on the Moon and asteroids. Planet Space Sci 59(14):1758–1768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pss.2011.04.017

Hemmi R, Miyamoto H (2020) Morphology and morphometry of sub-kilometer craters on the nearside of Phobos and implications for regolith properties. Trans Japan Soc Aero Space Sci 63(4):124–131. https://doi.org/10.2322/tjsass.63.124

Hildebrand AR, McCausland PJA, Brown PG, Longstaffe FJ, Russell SDJ, Tagliaferri E, Wacker JF, Mazur MJ (2006) The fall and recovery of the Tagish Lake meteorite. Meteorit Planet Sci 41(3):407–431. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1945-5100.2006.tb00471.x

Hiroi T, Zolensky ME, Pieters CM (2001) The Tagish Lake meteorite: a possible sample from a D-type asteroid. Science 293(5538):2234–2236. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1063734

Housen KR, Holsapple KA (2011) Ejecta from impact craters. Icarus 211(1):856–875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2010.09.017

Hu X, Shi X, Sierks H, Fulle M, Blum J, Keller HU, Kührt E, Davidsson B, Güttler C, Gundlach B, Pajola M, Bodewits D, Vincent JB, Oklay N, Massironi M, Fornasier S, Tubiana C, Groussin O, Boudreault S, Höfner S, Mottola S, Barbieri C, Lamy PL, Rodrigo R, Koschny D, Rickman H, A’Hearn M, Agarwal J, Barucci MA, Bertaux JL, Bertini I, Cremonese G, Da Deppo V, Debei S, De Cecco M, Deller J, El-Maarry MR, Gicquel A, Gutierrez-Marques P, Gutiérrez PJ, Hofmann M, Hviid SF, Ip WH, Jorda L, Knollenberg J, Kovacs G, Kramm JR, Küppers M, Lara LM, Lazzarin M, Lopez-Moreno JJ, Marzari F, Naletto G, Thomas N (2017) Seasonal erosion and restoration of the dust cover on comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko as observed by OSIRIS onboard Rosetta. Astron Astrophys. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201629910

Hurford TA, Asphaug E, Spitale JN, Hemingway D, Rhoden AR, Henning WG, Bills BG, Kattenhorn SA, Walker M (2016) Tidal disruption of Phobos as the cause of surface fractures. J Geophys Res: Planets 121(6):1054–1065. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015je004943

Hyodo R, Genda H, Charnoz S, Rosenblatt P (2017) On the impact origin of Phobos and Deimos. I. Thermodynamic and physical aspects. Astrophys J. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/aa81c4

Hyodo R, Kurosawa K, Genda H, Usui T, Fujita K (2019) Transport of impact ejecta from Mars to its moons as a means to reveal Martian history. Sci Rep-Uk. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-56139-x

Ivanov BA (2001) Mars/Moon cratering rate ratio estimates. Space Sci Rev 96(1–4):87–104. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011941121102

Izawa MRM, Flemming RL, King PL, Peterson RC, McCausland PJA (2010) Mineralogical and spectroscopic investigation of the Tagish Lake carbonaceous chondrite by X-ray diffraction and infrared reflectance spectroscopy. Meteorit Planet Sci 45(4):675–698. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1945-5100.2010.01043.x

Jacobson RA (2010) The orbits and masses of the Martian satellites and the Libration of Phobos. Astron J 139(2):668–679. https://doi.org/10.1088/0004-6256/139/2/668

Kring DA, Melosh HJ, Hunten DM (1996) Impact-induced perturbations of atmospheric sulfur. Earth Planet Sci Lett 140(1–4):201–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/0012-821x(96)00050-7

Kührt E, Giese B (1989) A thermal-model of the Martian satellites. Icarus 81(1):102–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/0019-1035(89)90128-0

Kührt E, Giese B, Keller HU, Ksanfomality LV (1992) Interpretation of the Krfm-infrared measurements of Phobos. Icarus 96(2):213–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/0019-1035(92)90075-I

Kuramoto K et al (2021) Martian moons exploration MMX: sample return mission to Phobos elucidating formation processes of habitable planet. Earth Planets Space. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-021-01545-7

Kuzmin RO, Shingareva TV, Zabalueva EV (2003) An engineering model for the Phobos surface. Solar Syst Res 37(4):266–281. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025074114117

Lauretta DS, DellaGiustina DN, Bennett CA, Golish DR, Becker KJ, Balram-Knutson SS, Barnouin OS, Becker TL, Bottke WF, Boynton WV, Campins H, Clark BE, Connolly HC, d'Aubigny CYD, Dworkin JP, Emery JP, Enos HL, Hamilton VE, Hergenrother CW, Howell ES, Izawa MRM, Kaplan HH, Nolan MC, Rizk B, Roper HL, Scheeres DJ, Smith PH, Walsh KJ, Wolner CWV, Highsmith DE, Small J, Vokrouhlicky D, Bowles NE, Brown E, Hanna KLD, Warren T, Brunet C, Chicoine RA, Desjardins S, Gaudreau D, Haltigin T, Millington-Veloza S, Rubi A, Aponte J, Gorius N, Lunsford A, Allen B, Grindlay J, Guevel D, Hoak D, Hong J, Schrader DL, Bayron J, Golubov O, Sanchez P, Stromberg J, Hirabayashi M, Hartzell CM, Oliver S, Rascon M, Harch A, Joseph J, Squyres S, Richardson D, McGraw L, Ghent R, Binzel RP, Al Asad MM, Johnson CL, Philpott L, Susorney HCM, Cloutis EA, Hanna RD, Ciceri F, Hildebrand AR, Ibrahim EM, Breitenfeld L, Glotch T, Rogers AD, Ferrone S, Thomas CA, Fernandez Y, Chang W, Cheuvront A, Trang D, Tachibana S, Yurimoto H, Brucato JR, Poggiali G, Pajola M, Dotto E, Epifani EM, Crombie MK, Lantz C, de Leon J, Licandro J, Garcia JLR, Clemett S, Thomas-Keprta K, Van Wal S, Yoshikawa M, Bellerose J, Bhaskaran S, Boyles C, Chesley SR, Elder CM, Farnocchia D, Harbison A, Kennedy B, Knight A, Martinez-Vlasoff N, Mastrodemos N, McElrath T, Owen W, Park R, Rush B, Swanson L, Takahashi Y, Velez D, Yetter K, Thayer C, Adam C, Antreasian P, Bauman J, Bryan C, Carcich B, Corvin M, Geeraert J, Hoffman J, Leonard JM, Lessac-Chenen E, Levine A, McAdams J, McCarthy L, Nelson D, Page B, Pelgrift J, Sahr E, Stakkestad K, Stanbridge D, Wibben D, Williams B, Williams K, Wolff P, Hayne P, Kubitschek D, Barucci MA, Deshapriya JDP, Fornasier S, Fulchignoni M, Hasselmann P, Merlin F, Praet A, Bierhaus EB, Billett O, Boggs A, Buck B, Carlson-Kelly S, Cerna J, Chaffin K, Church E, Coltrin M, Daly J, Deguzman A, Dubisher R, Eckart D, Ellis D, Falkenstern P, Fisher A, Fisher ME, Fleming P, Fortney K, Francis S, Freund S, Gonzales S, Haas P, Hasten A, Hauf D, Hilbert A, Howell D, Jaen F, Jayakody N, Jenkins M, Johnson K, Lefevre M, Ma H, Mario C, Martin K, May C, Mcgee M, Miller B, Miller C, Miller G, Mirfakhrai A, Muhle E, Norman C, Olds R, Parish C, Ryle M, Schmitzer M, Sherman P, Skeen M, Susak M, Sutter B, Tran Q, Welch C, Witherspoon R, Wood J, Zareski J, Arvizu-Jakubicki M, Asphaug E, Audi E, Ballouz RL, Bandrowski R, Bendall S, Bloomenthal H, Blum D, Brodbeck J, Burke KN, Chojnacki M, Colpo A, Contreras J, Cutts J, Dean D, Diallo B, Drinnon D, Drozd K, Enos R, Fellows C, Ferro T, Fisher MR, Fitzgibbon G, Fitzgibbon M, Forelli J, Forrester T, Galinsky I, Garcia R, Gardner A, Habib N, Hamara D, Hammond D, Hanley K, Harshman K, Herzog K, Hill D, Hoekenga C, Hooven S, Huettner E, Janakus A, Jones J, Kareta TR, Kidd J, Kingsbury K, Koelbel L, Kreiner J, Lambert D, Lewin C, Lovelace B, Loveridge M, Lujan M, Maleszewski CK, Malhotra R, Marchese K, McDonough E, Mogk N, Morrison V, Morton E, Munoz R, Nelson J, Padilla J, Pennington R, Polit A, Ramos N, Reddy V, Riehl M, Salazar S, Schwartz SR, Selznick S, Shultz N, Stewart S, Sutton S, Swindle T, Tang YH, Westermann M, Worden D, Zega T, Zeszut Z, Bjurstrom A, Bloomquist L, Dickinson C, Keates E, Liang J, Nifo V, Taylor A, Teti F, Caplinger M, Bowles H, Carter S, Dickenshied S, Doerres D, Fisher T, Hagee W, Hill J, Miner M, Noss D, Piacentine N, Smith M, Toland A, Wren P, Bernacki M, Munoz DP, Watanabe SI, Sandford SA, Aqueche A, Ashman B, Barker M, Bartels A, Berry K, Bos B, Burns R, Calloway A, Carpenter R, Castro N, Cosentino R, Donaldson J, Cook JE, Emr C, Everett D, Fennell D, Fleshman K, Folta D, Gallagher D, Garvin J, Getzandanner K, Glavin D, Hull S, Hyde K, Ido H, Ingegneri A, Jones N, Kaotira P, Lim LF, Liounis A, Lorentson C, Lorenz D, Lyzhoft J, Mazarico EM, Mink R, Moore W, Moreau M, Mullen S, Nagy J, Neumann G, Nuth J, Poland D, Reuter DC, Rhoads L, Rieger S, Rowlands D, Sallitt D, Scroggins A, Shaw G, Simon AA, Swenson J, Vasudeva P, Wasser M, Zellar R, Grossman J, Johnston G, Morris M, Wendel J, Burton A, Keller LP, McNamara L, Messenger S, Nakamura-Messenger K, Nguyen A, Righter K, Queen E, Bellamy K, Dill K, Gardner S, Giuntini M, Key B, Kissell J, Patterson D, Vaughan D, Wright B, Gaskell RW, Le Corre L, Li JY, Molaro JL, Palmer EE, Siegler MA, Tricarico P, Weirich JR, Zou XD, Ireland T, Tait K, Bland P, Anwar S, Bojorquez-Murphy N, Christensen PR, Haberle CW, Mehall G, Rios K, Franchi I, Rozitis B, Beddingfield CB, Marshall J, Brack DN, French AS, McMahon JW, Jawin ER, Mccoy TJ, Russell S, Killgore M, Bandfield JL, Clark BC, Chodas M, Lambert M, Masterson RA, Daly MG, Freemantle J, Seabrook JA, Craft K, Daly RT, Ernst C, Espiritu RC, Holdridge M, Jones M, Nair AH, Nguyen L, Peachey J, Perry ME, Plescia J, Roberts JH, Steele R, Turner R, Backer J, Edmundson K, Mapel J, Milazzo M, Sides S, Manzoni C, May B, Delbo M, Libourel G, Michel P, Ryan A, Thuillet F, Marty B, Team O-R (2019) The unexpected surface of asteroid (101955) Bennu. Nature 568 (7750):55–60. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1033-6

Le Maistre S, Rivoldini A, Rosenblatt P (2019) Signature of Phobos’ interior structure in its gravity field and libration. Icarus 321:272–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2018.11.022

Lee P (1996) Dust levitation on asteroids. Icarus 124(1):181–194. https://doi.org/10.1006/icar.1996.0197

Lunine JI, Neugebauer G, Jakosky BM (1982) Infrared observations of Phobos and Deimos from Viking. J Geophys Res 87(Nb12):297–305. https://doi.org/10.1029/JB087iB12p10297

Metzger PT, Britt DT, Covey S, Schultz C, Cannon KM, Grossman KD, Mantovani JG, Mueller RP (2019) Measuring the fidelity of asteroid regolith and cobble simulants. Icarus 321:632–646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2018.12.019

Michel P et al (2021) The MMX rover: performing in-situ surface investigations on Phobos. Earth Planets Space. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-021-01464-7

Miyamoto H, Niihara T (2020) Simplified simulated materials of asteroid ryugu for spacecraft operations and scientific evaluations. Nat Resour Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11053-020-09626-2

Miyamoto H, Yano H, Scheeres DJ, Abe S, Barnouin-Jha O, Cheng AF, Demura H, Gaskell RW, Hirata N, Ishiguro M, Michikami T, Nakamura AM, Nakamura R, Saito J, Sasaki S (2007) Regolith migration and sorting on asteroid Itokawa. Science 316(5827):1011–1014. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1134390

Miyamoto H, Hong PK, Niihara T, Kuritani T, Fukumizu K, Hino H, Nagata K, Akaho S, Rodriguez JAP, Ryodo H, Sugita S, Okada M (2018) Reflectance spectra of Asteroids and Meteorites: their classifications and statistical comparisons. J Phys: Conf Series. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1036/1/012003

Murchie S, Thomas N, Britt D, Herkenhoff K, Bell JF (1999) Mars pathfinder spectral measurements of Phobos and Deimos: comparison with previous data. J Geophys Res-Planet 104(E4):9069–9079. https://doi.org/10.1029/98je02248

Murchie SL, Britt DT, Pieters CM (2014) The value of Phobos sample return. Planet Space Sci 102:176–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pss.2014.04.014

Nakamura T, Noguchi T, Zolensky ME, Tanaka M (2003) Mineralogy and noble-gas signatures of the carbonate-rich lithology of the Tagish Lake carbonaceous chondrite: evidence for an accretionary breccia. Earth Planet Sci Lett 207:83–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-821X(02)01127-5

Niihara T, Beard SP, Swindle TD, Schaffer LA, Miyamoto H, Kring DA (2019) Evidence for multiple 4.0–3.7 Ga impact events within the Apollo 16 collection. Meteorit Planet Sci 54(4):675–698. https://doi.org/10.1111/maps.13237

Oieroset M, Brain DA, Simpson E, Mitchell DL, Phan TD, Halekas JS, Lin RP, Acuna MH (2010) Search for Phobos and Deimos gas/dust tori using in situ observations from Mars Global Surveyor MAG/ER. Icarus 206(1):189–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2009.07.017

Pajola M, Lazzarin M, Dalle Ore CM, Cruikshank DP, Roush TL, Magrin S, Bertini I, La Forgia F, Barbieri C (2013) Phobos as a D-type captured asteroid, spectral modeling from 0.25 to 4.0 μm. Astrophys J. https://doi.org/10.1088/0004-637x/777/2/127

Pätzold M, Andert T, Jacobson R, Rosenblatt P, Dehant V (2014) Phobos: observed bulk properties. Planet Space Sci 102:86–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pss.2014.01.004

Pieters CM, Hiroi T (2004) RELAB (Reflectance Experiment Laboratory): a NASA Multiuser Spectroscopy Facility. Paper presented at the 35th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, Houston

Pieters CM, Klima RL, Hiroi T, Dyar MD, Lane MD, Treiman AH, Noble SK, Sunshine JM, Bishop JL (2008) Martian dunite NWA 2737: integrated spectroscopic analyses of brown olivine. J Geophys Res-Planet. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007je002939

Pieters CM, Murchie S, Thomas N, Britt D (2014) Composition of surface materials on the moons of mars. Planet Space Sci 102:144–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pss.2014.02.008

Popel SI, Golub’ AP, Zakharov AV, Zelenyi LM (2019) Dusty plasmas at Martian satellites. J Phys Conf Ser. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1147/1/012110

Ramsley KR, Head JW (2013a) Mars impact ejecta in the regolith of Phobos: bulk concentration and distribution. Planet Space Sci 87:115–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pss.2013.09.005

Ramsley KR, Head JW (2013b) The origin of Phobos grooves from ejecta launched from impact craters on Mars: tests of the hypothesis. Planet Space Sci 75:69–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pss.2012.10.007

Richardson JE, Steckloff JK, Minton DA (2020) Impact-produced seismic shaking and regolith growth on asteroids 433 Eros, 2867 Šteins, and 25143 Itokawa. Icarus. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2020.113811

Rivkin AS, Brown RH, Trilling DE, Bell JF, Plassmann JH (2002) Near-infrared spectrophotometry of Phobos and Deimos. Icarus 156(1):64–75. https://doi.org/10.1006/icar.2001.6767

Robinson MS, Thomas PC, Veverka J, Murchie S, Carcich B (2001) The nature of ponded deposits on Eros. Nature 413(6854):396–400. https://doi.org/10.1038/35096518

Russell CT, Raymond CA, Coradini A, McSween HY, Zuber MT, Nathues A, De Sanctis MC, Jaumann R, Konopliv AS, Preusker F, Asmar SW, Park RS, Gaskell R, Keller HU, Mottola S, Roatsch T, Scully JEC, Smith DE, Tricarico P, Toplis MJ, Christensen UR, Feldman WC, Lawrence DJ, McCoy TJ, Prettyman TH, Reedy RC, Sykes ME, Titus TN (2012) Dawn at vesta: testing the protoplanetary paradigm. Science 336(6082):684–686. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1219381

Saito J, Miyamoto H, Nakamura R, Ishiguro M, Michikami T, Nakamura AM, Demura H, Sasaki S, Hirata N, Honda C, Yamamoto A, Yokota Y, Fuse T, Yoshida F, Tholen DJ, Gaskell RW, Hashimoto T, Kubota T, Higuchi Y, Nakamura T, Smith P, Hiraoka K, Honda T, Kobayashi S, Furuya M, Matsumoto N, Nemoto E, Yukishita A, Kitazato K, Dermawan B, Sogame A, Terazono J, Shinohara C, Akiyama H (2006) Detailed images of asteroid 25143 Itokawa from Hayabusa. Science 312(5778):1341–1344. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1125722

Sakatani N, Ogawa K, Iijima YI, Honda R, Tanaka S (2012) Experimental study for thermal conductivity structure of lunar surface regolith: effect of compressional stress. Icarus 221(2):1180–1182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2012.08.037

Sasaki S, Nakamura K, Hamabe Y, Kurahashi E, Hiroi T (2001) Production of iron nanoparticles by laser irradiation in a simulation of lunar-like space weathering. Nature 410(6828):555–557. https://doi.org/10.1038/35069013

Scheeres DJ, Van Wal S, Olikara Z, Baresi N (2019) Dynamics in the Phobos environment. Adv Space Res 63(1):476–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2018.10.016

Schmedemann N, Kneissl T, Ivanov BA, Michael GG, Wagner RJ, Neukum G, Ruesch O, Hiesinger H, Krohn K, Roatsch T, Preusker F, Sierks H, Jaumann R, Reddy V, Nathues A, Walter SHG, Neesemann A, Raymond CA, Russell CT (2014) The cratering record, chronology and surface ages of (4) Vesta in comparison to smaller asteroids and the ages of HED meteorites. Planet Space Sci 103:104–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pss.2014.04.004

Senshu H, Kimura H, Yamamoto T, Wada K, Kobayashi M, Namiki N, Matsui T (2015) Photoelectric dust levitation around airless bodies revised using realistic photoelectron velocity distributions. Planet Space Sci 116:18–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pss.2015.03.009

Shiomoto J, Nakamura A, Hasegawa N, Miyamoto H, Niihara T (2020) Laboratory collisional disruption experiments of D-type asteroids analogue targets. Paper presented at the JpGU-AGU Joint Meeting 2020

Showalter MR, Hamilton DP, Nicholson PD (2006) A deep search for Martian dust rings and inner moons using the Hubble Space Telescope. Planet Space Sci 54(9–10):844–854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pss.2006.05.009

Simonelli DP, Wisz M, Switala A, Adinolfi D, Veverka J, Thomas PC, Helfenstein P (1998) Photometric properties of Phobos surface materials from Viking images. Icarus 131(1):52–77. https://doi.org/10.1006/icar.1997.5800

Stoeser DB, Wilson SA, Fikes J, McLemore C, Rickman D (2008) Development of lunar highland regolith simulants, NU-LHT-1M, -2M. Geochimica Et Cosmochimica Acta Supplement 72:A902

Sugita S, Honda R, Morota T, Kameda S, Sawada H, Tatsumi E, Yamada M, Honda C, Yokota Y, Kouyama T, Sakatani N, Ogawa K, Suzuki H, Okada T, Namiki N, Tanaka S, Iijima Y, Yoshioka K, Hayakawa M, Cho Y, Matsuoka M, Hirata N, Hirata N, Miyamoto H, Domingue D, Hirabayashi M, Nakamura T, Hiroi T, Michikami T, Michel P, Ballouz RL, Barnouin OS, Ernst CM, Schroder SE, Kikuchi H, Hemmi R, Komatsu G, Fukuhara T, Taguchi M, Arai T, Senshu H, Demura H, Ogawa Y, Shimaki Y, Sekiguchi T, Muller TG, Hagermann A, Mizuno T, Noda H, Matsumoto K, Yamada R, Ishihara Y, Ikeda H, Araki H, Yamamoto K, Abe S, Yoshida F, Higuchi A, Sasaki S, Oshigami S, Tsuruta S, Asari K, Tazawa S, Shizugami M, Kimura J, Otsubo T, Yabuta H, Hasegawa S, Ishiguro M, Tachibana S, Palmer E, Gaskell R, Le Corre L, Jaumann R, Otto K, Schmitz N, Abell PA, Barucci MA, Zolensky ME, Vilas F, Thuillet F, Sugimoto C, Takaki N, Suzuki Y, Kamiyoshihara H, Okada M, Nagata K, Fujimoto M, Yoshikawa M, Yamamoto Y, Shirai K, Noguchi R, Ogawa N, Terui F, Kikuchi S, Yamaguchi T, Oki Y, Takao Y, Takeuchi H, Ono G, Mimasu Y, Yoshikawa K, Takahashi T, Takei Y, Fujii A, Hirose C, Nakazawa S, Hosoda S, Mori O, Shimada T, Soldini S, Iwata T, Abe M, Yano H, Tsukizaki R, Ozaki M, Nishiyama K, Saiki T, Watanabe S, Tsuda Y (2019) The geomorphology, color, and thermal properties of Ryugu: implications for parent-body processes. Science 364(6437):252. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw0422

Tachibana S, Sawada H, Okazaki R, Takano Y, Okamoto C, Yano H, Team H-S (2013) The sampling system of hayabusa-2: improvements from the hayabusa sampler. Paper presented at the 44th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, The Woodlands

Takemura T, Miyamoto H, Hemmi R, Niihara T, Michel P (2021) Small-scale topographic irregularities on Phobos: image and numerical analyses for MMX mission. Earth Planets Space. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-021-01463-8

Thomas PC (1993) Gravity, tides, and topography on small satellites and asteroids: application to surface features of the martian satellites. Icarus 105(2):326–344. https://doi.org/10.1006/icar.1993.1130

Tsuchiyama A, Mashio E, Imai Y, Noguchi T, Miura Y, Yano H, Nakamura T (2009) Strength Measurement of Carbonaceous Chondrites and Micrometeorites Using Micro Compression Testing Machine. Paper presented at the 72nd Annual Meeting of the Meteoritical Society, Nancy

Usui T, Bajo K, Fujiya W, Furukawa Y, Koike M, Miura YN, Sugahara H, Tachibana S, Takano Y, Kuramoto K (2020) The importance of Phobos sample return for understanding the mars-moon system. Space Sci Rev. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-020-00668-9

Veverka J, Robinson M, Thomas P, Murchie S, Bell JF 3rd, Izenberg N, Chapman C, Harch A, Bell M, Carcich B, Cheng A, Clark B, Domingue D, Dunham D, Farquhar R, Gaffey MJ, Hawkins E, Joseph J, Kirk R, Li H, Lucey P, Malin M, Martin P, McFadden L, Merline WJ, Miller JK (2000) NEAR at eros: imaging and spectral results. Science 289(5487):2088–2097. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.289.5487.2088

Veverka J, Thomas PC, Robinson M, Murchie S, Chapman C, Bell M, Harch A, Merline WJ, Bell JF 3rd, Bussey B, Carcich B, Cheng A, Clark B, Domingue D, Dunham D, Farquhar R, Gaffey MJ, Hawkins E, Izenberg N, Joseph J, Kirk R, Li H, Lucey P, Malin M, McFadden L, Miller JK, Owen WM Jr, Peterson C, Prockter L, Warren J, Wellnitz D, Williams BG, Yeomans DK (2001) Imaging of small-scale features on 433 Eros from NEAR: evidence for a complex regolith. Science 292(5516):484–488. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1058651

Walsh KJ (2018) Rubble pile asteroids. Annu Rev Astron Astr 56(1):593–624. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-astro-081817-052013

Wang Y, Wu XJ (2020) Analysis of Phobos’ dynamical environment considering effects of ephemerides and physical libration. Mon Not R Astron Soc 497(1):416–434. https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/staa1948

Wang X, Schwan J, Hsu HW, Grün E, Horányi M (2016) Dust charging and transport on airless planetary bodies. Geophys Res Lett 43(12):6103–6110. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016gl069491

Watanabe S, Hirabayashi M, Hirata N, Hirata N, Noguchi R, Shimaki Y, Ikeda H, Tatsumi E, Yoshikawa M, Kikuchi S, Yabuta H, Nakamura T, Tachibana S, Ishihara Y, Morota T, Kitazato K, Sakatani N, Matsumoto K, Wada K, Senshu H, Honda C, Michikami T, Takeuchi H, Kouyama T, Honda R, Kameda S, Fuse T, Miyamoto H, Komatsu G, Sugita S, Okada T, Namiki N, Arakawa M, Ishiguro M, Abe M, Gaskell R, Palmer E, Barnouin OS, Michel P, French AS, McMahon JW, Scheeres DJ, Abell PA, Yamamoto Y, Tanaka S, Shirai K, Matsuoka M, Yamada M, Yokota Y, Suzuki H, Yoshioka K, Cho Y, Tanaka S, Nishikawa N, Sugiyama T, Kikuchi H, Hemmi R, Yamaguchi T, Ogawa N, Ono G, Mimasu Y, Yoshikawa K, Takahashi T, Takei Y, Fujii A, Hirose C, Iwata T, Hayakawa M, Hosoda S, Mori O, Sawada H, Shimada T, Soldini S, Yano H, Tsukizaki R, Ozaki M, Iijima Y, Ogawa K, Fujimoto M, Ho TM, Moussi A, Jaumann R, Bibring JP, Krause C, Terui F, Saiki T, Nakazawa S, Tsuda Y (2019) Hayabusa2 arrives at the carbonaceous asteroid 162173 Ryugu-A spinning top-shaped rubble pile. Science 364(6437):268–272. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aav8032

Willman BM, Boles WW, McKay DS, Allen CC (1995) Properties of lunar soil simulant JSC-1. J Aerospace Eng 8(2):77–87. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)0893-1321(1995)8:2(77)

Willner K, Oberst J, Hussmann H, Giese B, Hoffmann H, Matz KD, Roatsch T, Duxbury T (2010) Phobos control point network, rotation, and shape. Earth Planet Sci Lett 294(3–4):541–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2009.07.033

Willner K, Shi X, Oberst J (2014) Phobos’ shape and topography models. Planet Space Sci 102:51–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pss.2013.12.006

Wilson L, Keil K, Browning LB, Krot AN, Bourcier W (1999) Early aqueous alteration, explosive disruption, and reprocessing of asteroids. Meteorit Planet Sci 34(4):541–557. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1945-5100.1999.tb01362.x

Yang X, Yan JG, Andert T, Ye M, Patzold M, Hahn M, Jin WT, Li F, Barriot JP (2019) The second-degree gravity coefficients of Phobos from two Mars Express flybys. Mon Not R Astron Soc 490(2):2007–2012. https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stz2695

Yano H, Kubota T, Miyamoto H, Okada T, Scheeres D, Takagi Y, Yoshida K, Abe M, Abe S, Barnouin-Jha O, Fujiwara A, Hasegawa S, Hashimoto T, Ishiguro M, Kato M, Kawaguchi J, Mukai T, Saito J, Sasaki S, Yoshikawa M (2006) Touchdown of the Hayabusa spacecraft at the Muses Sea on Itokawa. Science 312(5778):1350–1353. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1126164

Yoder CF (1982) Tidal rigidity of Phobos. Icarus 49(3):327–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/0019-1035(82)90040-9

Zeng X, Li X, Martin DJP, Tang H, Yu W, Yang K, Wang Z, Wang S (2019) The Itokawa regolith simulant IRS-1 as an S-type asteroid surface analogue. Icarus 333:371–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2019.06.011

Zolensky ME, Nakamura K, Gounelle M, Mikouchi T, Kasama T, Tachikawa O, Tonui E (2002) Mineralogy of Tagish Lake: an ungrouped type 2 carbonaceous chondrite. Meteorit Planet Sci 37(5):737–761. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1945-5100.2002.tb00852.x

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the ore and industrial machinery companies of Ube Kyourisu Sangyou Inc., Fusukawa Industrial Machinery Systems Co. Ltd., Sanshin Mining Ind. Co. Ltd., and Hatanaka Syouwa Inc. for providing various types of rock and minerals and their professional knowledge. We especially appreciate Yoshizawa Lime Industry Co., Ltd. for providing raw materials and professional expertise on crushing processes. We appreciate Prof. Katsunori Fukui for his help in obtaining raw materials. This work is financially supported by JAXA/ISAS. P.M. and M.A.B acknowledges CNES for funding support. E.A. acknowledge support from University of Arizona. DTB acknowledges support from the NASA the Solar System Exploration Research Virtual Institute (SSERVI) and the Center for Lunar and Asteroid Surface Science (CLASS) under Cooperative Agreement 80NSSC19M0214.

Funding

This work is financially supported by JAXA/ISAS. P.M. and M.A.B acknowledge CNES for funding support. E.A. acknowledges support from University of Arizona.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions