Abstract

Phobos and Deimos occupy unique positions both scientifically and programmatically on the road to the exploration of the solar system. Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) plans a Phobos sample return mission (MMX: Martian Moons eXploration). The MMX spacecraft is scheduled to be launched in 2024, orbit both Phobos and Deimos (multiple flybys), and retrieve and return >10 g of Phobos regolith back to Earth in 2029. The Phobos regolith represents a mixture of endogenous Phobos building blocks and exogenous materials that contain solar system projectiles (e.g., interplanetary dust particles and coarser materials) and ejecta from Mars and Deimos. Under the condition that the representativeness of the sampling site(s) is guaranteed by remote sensing observations in the geologic context of Phobos, laboratory analysis (e.g., mineralogy, bulk composition, O-Cr-Ti isotopic systematics, and radiometric dating) of the returned sample will provide crucial information about the moon’s origin: capture of an asteroid or in-situ formation by a giant impact. If Phobos proves to be a captured object, isotopic compositions of volatile elements (e.g., D/H, 13C/12C, 15N/14N) in inorganic and organic materials will shed light on both organic-mineral-water/ice interactions in a primitive rocky body originally formed in the outer solar system and the delivery process of water and organics into the inner rocky planets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The Mars-moon system is a most promising target for exploration in the broad field of planetary science: e.g., geology, geochemistry, astrobiology, and comparative planetology. The international Mars science community has set a long-term goal toward achieving Mars sample return (MSR) and human exploration (Banfield 2018). MSR will address questions on the origin (e.g., source of building blocks), interior evolution (e.g., crust-mantle differentiation and mantle dynamics), the potential biological history (e.g., nature and extent of habitability and preservation of biosignature), and geologic history of Mars with an emphasis on the role of water (Beaty et al. 2019). Previous Mars exploration missions have provided compelling evidence for the presence of liquid water during the earliest geologic era (Noachian: >∼3.9 Ga) of Mars. Observations of dense valley networks, evaporites (e.g., gypsum) and hydrous minerals (e.g., clays) that are commonly formed by aqueous processes imply that, at some time in the past, Mars had an Earth-like active hydrological cycle with lakes, oceans, possibly also aquifers and groundwater, and had the potential for life (Carr 2006; Ehlmann et al. 2016; Usui 2019).

Along with the geological similarities, Earth and Mars are the only terrestrial planets in the inner solar system that have moons. The moons are witness plates for planet formation processes. Lunar exploration and studies of lunar samples (Apollo and meteorites) in the lab provided significant knowledge of the formation and co-evolution of the Earth-Moon system: e.g., the giant impact and magma ocean hypotheses for terrestrial planet formation, and the late veneer hypothesis for the delivery of water into the inner solar system (e.g., Taylor et al. 2006; Day et al. 2016). These hypotheses may also be tested for the Mars system by virtue of studying Phobos and Deimos. However, our understanding of Phobos and Deimos is sparse mainly due to the complete lack of successful missions dedicated to the exploration of Phobos/Deimos as well as the lack of meteorites from these bodies. The Soviet Union’s Phobos 2 spacecraft acquired television images and infrared spectra at ∼700 m/pixel resolution (Avanesov et al. 1989; Bibring et al. 1990). Subsequent observations have been made by Earth-based telescopes and Mars orbiters/landers reporting a surface spectral similarity to D-type asteroid (e.g.,Murchie and Erard 1996; Simonelli et al. 1998; Cantor et al. 1999; Thomas et al. 2011; Fraeman et al. 2012; Fraeman et al. 2014). Therefore, Phobos and Deimos occupy unique positions both scientifically and programmatically on the road to the exploration of the solar system (Murchie et al. 2014).

The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) plans a Martian moons’ sample return mission (MMX: Martian Moons eXploration) (Kuramoto et al. 2018; Usui et al. 2018); MMX is the 3rd Japanese sample return mission, following Hayabusa (Fujiwara et al. 2006) and Hayabusa2 (Watanabe et al. 2019). The origin(s) of Phobos and Deimos is still a matter of significant debate, with the most likely candidates being: 1) the capture of asteroids (e.g., Hartmann 1990; Higuchi et al. 2017) or 2) in-situ formation by either co-accretion (Safronov et al. 1986) or by a giant impact (e.g., Rosenblatt et al. 2016; Hesselbrock and Minton 2017; Hyodo et al. 2017) on Mars (Table 1). In either case, samples from a Martian moon returned by MMX will provide the necessary ground truth to test these theories and to offer an opportunity to directly explore the building blocks or juvenile crust/mantle components of Mars. This new knowledge of Phobos/Deimos and Mars will be further leveraged by constraining the initial condition of the Mars-moon system and has potential for offering vital insights regarding the sources and delivery process of volatiles including water and organics to the inner rocky planets. This paper describes the science goals, mission profile and science payload of the MMX mission (Sect. 2), summarizes the expected characteristics of the returned samples and the prospective scientific outcome from the laboratory analysis (Sects. 3-5), and describes an assessment of contamination control issues (Sect. 6).

2 Mission Overview

2.1 Mission Goals and Objectives

MMX has two main science goals: Goal-1) to reveal the origin of the Martian moons and make progress in the understanding of planetary system formation and material transport in the solar system, and Goal-2) to observe processes that impact the circumplanetary and surface environments of Mars (Fig. 1). These mission goals lead to the five mission objectives (MO): MO-1.1) to determine whether the origin of Phobos was by capture of an asteroid or by in-situ formation following a giant impact on Mars; MO-1.2) to understand material transport within the Mars-system during the moon formation stage; MO-1.3) to constrain the origin of Deimos; MO-2.1) to obtain a basic picture of surface processes acting on airless small bodies in orbit around Mars; MO-2.2) to gain critical new insight on Mars surface environment evolution; and MO2.3) to better understand the behavior of the Mars atmosphere-surface system and water cycle dynamics. To accomplish the science goals and objectives, the MMX team has defined a mission profile, has selected a comprehensive suite of remote-sensing and in-situ instruments, designed the Phobos regolith sampling system, and will conduct laboratory analyses of returned samples. Analyses of endogenous Phobos constituent materials and exogeneous late accreted materials would specifically achieve the mission goals-1 and -2, respectively (Sect. 3).

2.2 Mission Profile and Science Payload

The MMX spacecraft is scheduled to be launched in 2024, orbit Phobos and Deimos, perform multiple flybys, and retrieve and return >10 g of Phobos regolith back to Earth in 2029 (Kawakatsu et al. 2017). The spacecraft will consist of propulsion, exploration, and return modules (total launch mass = ∼4,000 kg). The chemical propulsion system is utilized for Mars orbit injection and an escape maneuver. The outward interplanetary flights will take ∼1 year by the most efficient Hohmann-like transfer. The spacecraft will remain in circum-Mars orbits for approximately 3 years for survey and exploration, followed by the ∼1 year homeward interplanetary journey to Earth. The Phobos exploration phase will include multiple landing/sampling operations, each taking ∼2.5 hours. To prevent sample contamination from thruster plume products and regolith particles that could be ejected from the surface during a thrust descent, the spacecraft will employ ballistic descent to reach a point directly above a landing site before a final free-fall descent without a thruster jet (Kawakatsu et al. 2017; Kawakatsu et al. 2019).

Seven nominal science instruments comprise several payloads for the remote sensing observations (Kuramoto et al. 2018): 1) a narrow-angle camera (TElescopic Nadir imager for GeOmOrphology, TENGOO) (JAXA) (Kameda et al. 2019), 2) a wide-angle multi-spectral camera (Optical RadiOmeter composed of CHromatic Imagers, OROCHI) (JAXA) (Kameda et al. 2019), 3) a near-infrared spectrometer (0.9-3.6 μm) MMX Infrared Spectrometer, MIRS (CNES), 4) a light detection and ranging instrument (LIDAR) (JAXA), 5) a dust instrument for particle sizes >10 μm (Circum-Martian Dust Monitor, CMDM) (JAXA) (Kobayashi et al. 2018), 6) a gamma-ray and neutron instrument (Mars-moon Exploration with GAmma rays and Neutrons, MEGANE) (NASA) (Lawrence et al. 2019), and 7) an ion mass spectrometer (Mass Spectrum Analyzer, MSA) (JAXA). Along with these seven instruments, the MMX spacecraft will carry and deploy a Rover (CNES/DLR) for in-situ surface exploration (Ulamec et al. 2019). The rover will carry several instruments for in-situ observations, including a Raman spectrometer, radiometer as well as navigation and wheel cameras.

2.3 Sampling System

Samples collected by MMX are expected to represent a mixture of endogenous and exogenous materials in Phobos’ regolith. The former represents Phobos’ building blocks that record information of the moon’s origin, while the latter is expected to contain solar system projectiles and ejecta derived from Mars and Deimos (Ramsley and Head 2013; Nayak et al. 2016; Hyodo et al. 2019). Although the depth profile of Phobos regolith regarding material distribution is unknown, the ratio of [exogenous /endogenous] abundances is expected to be highest at the top-most regolith layer, which is where sampling will occur.

MMX plans to employ a double sampling approach: (C) coring and (P) pneumatic. The C-sampler has more than two core soil tubes deployed by a robotic arm; each core has a volume large enough to collect >10 g regolith. The cores would provide access to material beneath the surface (>2 cm) but would collect a mixture of surface and sub-surface materials. The P-sampler, on the other hand, selectively samples the surface veneer and provides a reference of surface components for the C-sampler. The P-sampler will also increase the chance of retrieving invaluable Martian and Deimos materials. Each core sample retrieved by the C-sampler and surface materials collected by the P-sampler will be separately stored in different canisters and returned to Earth. Thus, the C- and P-samplers would constitute complementary approaches to addressing the MMX mission goals.

The double sampling system not only enhances the scientific merits of MMX, but also reduces risks associated with the coring system. The nominal landing operation will execute both C- and P-sampling at each landing site. However, lacking knowledge of physical and chemical properties and conditions of the surface of Phobos (e.g., compositions, temperature gradient/variation, porosity, grain size distribution), we will prepare for scenarios in which the C-sampler cannot penetrate deep enough into a thin regolith layer covering a rigid basement and/or that it cannot be extracted once it has penetrated. Under any conceivable surface conditions, the P-sampler will work effectively and independently to collect fine-grained regolith particles.

3 Expected Characteristics of Returned Samples

3.1 Phobos’ Original Building Blocks

3.1.1 A Case of the Captured Asteroid Hypothesis

The characteristics of the returned endogenous samples depend on Phobos’ origin (Table 1). In the case of captured asteroid origin (e.g., Hartmann 1990; Higuchi et al. 2017), the returned samples would be analogous to a certain type of chondrites, IDPs (interplanetary dust particles), or even comets, depending on where these moons originally formed in the early solar system. If they formed in the outer solar system (beyond the snow line), they could potentially contain abundant hydrous secondary phases and organic molecules. Such phases could have formed by water-rock-organic interaction under low-temperature conditions in the parent asteroid of Phobos, represented by H-, C-, and N-rich bulk chemistry (Alexander et al. 2012; Krot et al. 2015). Outer solar system formation could be also indicated by crystalline/amorphous silicate dust mixtures with a solar nebular origin, as found with the comet Wild-2 samples returned by the Stardust spacecraft (Brownlee et al. 2006). On the other hand, if the Martian moons formed in the inner solar system (inside of the snow line), they probably consist mostly of anhydrous phases with lower bulk volatile contents and characteristic isotopic differences. These two extreme cases for the captured model may be tested on the basis of the heliocentric gradients of volatile isotopes and abundances (e.g., CO2/H2O, D/H, 15N/14N and noble gases) and the isotopes of rock-forming elements of O, Cr, and Ti in the solar system (Figs. 2, 3, and 4) (Trinquier et al. 2007; Trinquier et al. 2009; Qin et al. 2010; Warren 2011; Marty 2012; Fujiya et al. 2019).

Histogram of the CO2/H2O mole ratios of ice in CM chondrites and comets. The CO2/H2O ratios of ice in CM chondrites are calculated from carbonate abundances and hydrogen contents. Modified after Fujiya et al. (2019)

D/H and 15N/14N ratios among solar system reservoirs and objects. The hatched area in A is enlarged B. Modified after Marty (2012)

3.1.2 A Case of In-Situ Formation

If Phobos and Deimos formed in-situ by a giant impact (like the Earth’s moon) (e.g., Rosenblatt et al. 2016; Hesselbrock and Minton 2017; Hyodo et al. 2017), the returned samples would be characterized by high-temperature and possibly high-pressure shocked phases and/or glassy/recrystallized phases. Due to the high-temperature impact process (e.g., ∼2000 K, Hyodo et al. 2017), endogenous organic materials would be unlikely to be present to a significant degree in the regolith. The bulk chemistry could range from a mafic to ultramafic composition with high abundances of highly siderophile elements, possibly representing a mixture of Martian silicate portions (crust/mantle) and the impactor (Hyodo et al. 2017). The bulk-silicate Mars is characterized by elevated volatile (e.g., Na and K) and siderophile (e.g., Mn, Cr, and W) elements and depletions in chalcophile elements (e.g., Cu), relative to the bulk silicate Earth (Dreibus and Wanke 1985; Taylor 2013). Such a volatile-rich nature relative to the Earth and Moon is evident in ratios of K/Th and K/U (volatile/refractory incompatible element) (Fig. 5) and the K/Th ratio of Phobos surface will be measured by MEGANE (Lawrence et al. 2019). On the other hand, in-situ formation by co-accretion with Mars would provide a bulk chemistry represented by the chondritic bulk Mars.

K/Th and K/U ratios of terrestrial bodies within the inner Solar System plotted as a function of heliocentric distance (McCubbin et al. 2012)

3.2 Late Accreted Materials

The regolith of Phobos is likely to contain ejecta derived from Mars and Deimos due to Phobos’ location in Mars’ orbit (Ramsley and Head 2013; Nayak et al. 2016; Hyodo et al. 2019). Though the exact nature of Deimos-originating material is unknown, the spectral similarity between Deimos and the dominant red unit of Phobos suggests that Deimos-originating materials resemble the endogenous Phobos materials (Fraeman et al. 2012); note that Phobos’ surface shows two distinct units named “blue unit” and “red unit” after the relative slopes of their reflectance spectra (Murchie and Erard 1996). We may have difficulty in discriminating Deimos-originating materials from the Phobos regolith unless detailed remote sensing observations by MMX clarify the distinction between the two moons. On the other hand, Mars-originating materials would differ from the endogenous Phobos materials even if Phobos was formed by a giant impact. The endogenous Phobos material formed by a giant impact should have sampled both crust and mantle reservoirs of Mars (Hyodo et al. 2017), whereas the later Mars-originating materials would have mostly derived from the near-surface of Mars (Hyodo et al. 2019). The Martian near-surface materials have oxygen (\(\Delta ^{17}\)O), hydrogen (D/H), and carbon (\(\delta ^{13}\)C) isotopic compositions that are distinct from those of the Martian crust and mantle reservoirs (Leshin et al. 1996; Farquhar and Thiemens 2000; Usui et al. 2012; Agee et al. 2013; Webster et al. 2013; Usui et al. 2015).

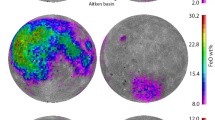

The surface of Mars is dominated by a basaltic crust mainly composed of olivine, pyroxene, and plagioclase (McSween et al. 2009) (Fig. 6). Although these igneous phases are common in chondrites and achondrites, their chemistries are distinct (e.g., Fe/Mg and Fe/Mn ratios, and anorthite component) (Karner et al. 2003; Karner et al. 2006). The Martian crust also contains a variety of sedimentary rocks, including both clastic rocks (sandstone and siltstone, shale and mudstone, and conglomerate) and chemically deposited rocks (mostly evaporitic sulfate, and some carbonate) (McSween 2015). Sedimentary rocks in ancient terranes potentially contain organic compounds (Eigenbrode et al. 2018). Global mapping of sedimentary rocks suggests the secular desiccation and acidification of the near-surface environment (Bibring et al. 2006; Ehlmann and Edwards 2014) (Fig. 7). The surface mineralogy of early Noachian terranes is characterized by clay minerals such as Fe/Mg smectites, suggesting water-rich and near-neutral fluid conditions. The occurrence and distribution of carbonates and sulfates in the late Noachian to early Hesperian suggest a transition of fluid chemistry to more acidic conditions in this period. The young Amazonian terranes are dominated by anhydrous ferric oxides such as hematite, suggestive of acidic and drier conditions. Meteorite impacts would have randomly sampled these Martian surficial materials, some of which would have subsequently been deposited on the surface of Phobos as late accreting materials in the regolith (Hyodo et al. 2019).

Compositions of Martian igneous rocks (McSween 2015)

Timeline of the evolution of magnetosphere, atmosphere, hydrosphere, cryosphere, and surface mineralogy of Mars. Age distribution of Martian meteorites are also plotted (Hyodo et al. 2019)

4 Key Analysis of Phobos Sample Return Mission

Compelling evidence for Phobos’ origin will be provided by high precision isotopic analyses of lithophile elements. Stable isotopic systematics of O, Cr, Ti, and Mo clearly differentiate the carbonaceous and non-carbonaceous reservoirs (Fig. 2), which are proposed to be spatially distinguished either side of Jupiter’s orbit (Trinquier et al. 2007; Trinquier et al. 2009; Qin et al. 2010; Warren 2011; Kruijer et al. 2017). A suite of these isotope analyses, except for Mo, can be carried out using a <100 mg fraction of the returned samples (Table 2). Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS) techniques further permit grain-by-grain characterization by high-spatial-resolution and high-precision O isotope analysis with a primary ion beam of ∼15 μm in size and analytical uncertainties of ∼0.5\(\permil \) for \(\Delta ^{17}\)O values (Kita et al. 2010; Yurimoto et al. 2011), potentially providing individual histories of each collected grain. Isotopic data will also be carefully examined alongisde petrographic and mineralogical observations to help discriminate the exogenous materials. For example, major element mineral chemistry of olivine and pyroxene, phases that are common in planetary materials, is distinct between asteroids (chondrite/achondrite parent bodies) and Mars (Brearley 1998; McSween and Treiman 1998; Mittlefehldt et al. 1998). Other lines of evidence for Phobos’ origin would also come from the presence/lack of refractory inclusions, amorphous silicates, presolar grains, or organic materials with anomalous H, C, and N isotopic compositions.

Radiometric dating of the returned samples would provide chronological constraints on the origin of Phobos. Mineral isochrons of 87Rb-87Sr, 147,146Sm-143,142Nd, 176Lu-176Hf, and 238,235U-206,207Pb systems obtained by Thermal Ionization Mass Spectrometry (TIMS) and Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) could yield formation ages (e.g., timing of crystallization) of individual fragments in the returned regolith sample (e.g., Amelin et al. 2002; Borg et al. 2005; Lapen et al. 2010). Bulk isochron defined by co-genetic fragments in the regolith sample could yield a formation age of the source (e.g., timing of the giant impact). Chronological study of short-lived nuclides (e.g., 146Sm-142Nd, 182Hf-182W, 53Mn-53Cr) would provide more precise knowledge of formation ages (e.g., Kleine et al. 2002; Trinquier et al. 2008; Kruijer et al. 2014). The 40K(39Ar)-40Ar age could represent the timing of a secondary impact on Phobos. Should a statistically meaningful number of 40K(39Ar)-40Ar ages be obtained, they would provide the chronometric ground truth for the crater density distribution obtained by MMX’s remote sensing observations. Furthermore, in-situ dating of secondary phases (e.g., 53Mn-53Cr age of carbonate) would provide the timing of secondary aqueous alteration events (Fujiya et al. 2012). Temperature of aqueous alteration would be estimated by C-O clumped isotope thermometry (e.g., Halevy et al. 2011).

Organic analysis plays an essential role in the Phobos sample return mission because the regolith of Phobos is expected to contain mature organics derived from the surface of Mars (Eigenbrode et al. 2018; Hyodo et al. 2019). If Phobos is a captured asteroid that formed in the outer solar system then the regolith could also contain a mixture of primitive compounds originating from its parent body (Table 1). In such a case, the MMX sample will expand knowledge about the primitive asteroids Ryugu and Bennu, the target bodies of Hayabusa 2 (Watanabe et al. 2019) and OSIRIS-REx (Lauretta et al. 2019) sample return missions, respectively. The MMX sample would be further important for organic astrochemistry, because Phobos has stayed in Mars’ orbit (∼1.5 AU), maintaining average surface temperatures lower than those of near-Earth asteroids Ryugu and Bennu.

Considering our experience with these sample return missions, Phobos sample return requires a comprehensive framework to maximize the scientific harvest through a seamless pathway from non-destructive to semi-destructive and destructive analysis (Table 2). In this workflow, bulk chemical analysis and molecular-based organic analysis will contribute to the careful documentation of volatile organic gas, soluble organic matter, insoluble organic matter, and remaining organic chemistry. For example, compound-specific isotope analyses of hydrogen (D/H), carbon (13C/12C), and nitrogen (15N/14N) by destructive (e.g., gas chromatography/isotope ratio mass spectrometry) and non-destructive (e.g., cavity ring-down spectroscopy) techniques would provide quantitative estimates of the low-temperature reactions between inorganic phases and organic molecules, many of which occur during aqueous alteration of anhydrous phases (Pizzarello et al. 2001; Kminek et al. 2002). The behavior of elements, isotopes, and molecules in micron-scale regions of interest can be measured by two dimensional-liquid chromatography/fluorescence detector system (2D-LC/FLD) and gas chromatography mass spectrometry (2D-GC/MS) in order to monitor these small-scale organic-mineral-water/ice interactions. These mass spectrometry analyses will complement spectroscopic analytical techniques of scanning transmission x-ray microscopy (STXM), and micro-Raman and infrared (IR) spectroscopy (e.g., Yabuta et al. 2014; Kitajima et al. 2015).

5 Sample Representativeness

To reveal the origin of the Martian moons (Goal-1, Fig. 1), one should evaluate the representativeness of the returned sample in the geologic context of Phobos understood from remote sensing observations; otherwise, the origin of individual grains analyzed by detailed laboratory analyses cannot directly reveal the moon’s origin. The surface of Phobos is geologically diverse, which is evident in the spectral difference between the blue unit located around Stickney crater and the red unit found on the remainder of Phobos’ surface (Murchie and Erard 1996). Basilevsky et al. (2014) suggest that the red and blue materials might have formed from large blocks originating in the interior of Phobos, although the actual cause of the spectral difference between the red and blue units is still unclear. A comprehensive and high spatial resolution analysis of reflectance spectra obtained by OROCHI and MIRS will document the distribution and mutual relations of the red and blue units in detail. Furthermore, subsurface (<1 m) chemical information of Phobos’ surface obtained by MEGANE and in-situ surface observations to be provided by the rover in the vicinity of the landing site will establish the representativeness of the returned sample.

6 Sample Assessment for Martian Moon Sample Return

Sample return missions offer sample analysis potential that is not otherwise achievable in-situ via the present generation of robotic planetary exploration missions. Nonetheless, preserving the integrity of returned samples to produce meaningful results requires that terrestrial contamination is understood, controlled, and minimized. Planetary protection regulations also serve to prevent the returned samples from contaminating the Earth. Thus, any sample return mission must take into account contamination assessment through design, manufacture, construction, testing, launch, flight and recovery.

MMX will be the first mission to return Phobos regolith to Earth. Sample return of Phobos regolith was classified as an unrestricted Earth-return mission by the Committee on Space Research (COSPAR) (Fujita et al. 2019; Kurosawa et al. 2019). Although MMX is unrestricted, the Phobos regolith is expected to contain a variety of volatile-bearing phases and organics, similar to the C-class asteroid target for the Hayabusa2 mission (Table 1). Thus, MMX has inherited the contamination assessment, control procedures, and practical knowledge of Hayabusa2 (Tachibana et al. 2014; Okazaki et al. 2017; Sawada et al. 2017).

Hayabusa2 is an unrestricted Earth-return mission from the carbonaceous asteroid 162173 Ryugu (Watanabe et al. 2019). The sample catcher and container of Hayabusa2 are designed to avoid terrestrial contamination of volatile and non-volatile organic and inorganic materials into the returned sample container (Okazaki et al. 2017; Sawada et al. 2017). To maintain the interior pressure and the chemical information of the initial gas components originating from the Ryugu sample, the maximum leak rate permitted to mitigate the atmospheric contamination is <1 Pa for 100 hours at one atmosphere. These conditions will preserve the isotope analyses of highly volatile elements such as H, N, and noble gases. For the assembly, test, and launch operations (ATLO) for Hayabusa2, spacecraft cleanliness was carefully monitored. Immediately upon return to Earth, the Hayabusa2 sample container will be brought to the curation facility at ISAS/JAXA for the recovery and initial classification of the sample (Tachibana et al. 2014). The assessment of the organic terrestrial contamination in the curation facility was conducted by analyzing amino acids as an indicator molecule collected on witness coupons (∼ below the order of pico mole \(\mbox{cm}^{-2}\,\mbox{day}^{-1}\)) (Sugahara et al. 2018).

Each sample return mission has a different contamination control policy, as defined by the mission requirements. For MMX, accurate analyses of stable isotope ratios of O, Cr, and Ti in bulk samples are given the highest priority because these are the most important indicators of sample origin (Mission Goal-1) (Fig. 2). We must reduce possible contamination of these elements throughout the mission by <1/1000 of the expected amounts in the samples so that we can distinguish isotopic signatures characterized by individual meteorite groups. Moreover, Mars-originating exogenous materials in the Phobos regolith are expected to contain sedimentary phases that would be rich in volatile elements. Their pristine geochemical information, such as water contents of clays and isotopic compositions of volatiles (H, C, N, O, and S), would also provide important clues for understanding the co-evolution of circum-Mars environments (Mission Goal-2) (Fig. 7).

We will leverage previously acquired knowledge from Hayabusa2 to optimize MMX’s ATLO and curation protocols for the Phobos sample return. A critical difference in the sample assessment between MMX and Hayabusa2 is the returned sample mass; the expected minimum sample amounts are 0.1 g for Hayabusa2 and 10 g for MMX. The larger sample amount for MMX should reduce the relative degree of terrestrial contamination because the “cleanliness” is defined by a relative fraction of foreign material to the returned sample in an amount that degrades the ability to analyze the chemistry and mineralogy of the sample. For example, NASA’s OSIRIS-REx asteroid sample return mission set the contamination allowance level of the organic carbon contaminants to ±30% precision and accuracy on measurements based on the National Research Council’s recommendation (Dworkin et al. 2018).

7 Conclusions

MMX has two mission goals: 1) to reveal the origin of the Martian moons and 2) to observe processes that impact on the evolution of the circum-Mars environment (Fig. 1). These mission goals will be achieved by comprehensive remote sensing observations of Phobos and Deimos and by laboratory analyses of a regolith sample returned from Phobos. Operation of C- and P-samplers will provide access to both Phobos’ subsurface building blocks (> 2 cm deep) and the top-most regolith layer, resulting in a total of >10 g of Phobos regolith returned to Earth. The regolith of Phobos likely represents a mixture of endogenous Phobos materials and exogenous materials that accumulated after the moon’s formation. Laboratory analyses of these two kinds of materials would allow successful achievement of the critical mission goals.

The characteristics of the endogenous Phobos materials depend on the moon’s origin. In the case of the captured asteroid scenario, they would be analogous to a certain type of chondrites. On the other hand, if Phobos formed in-situ by a giant impact, the endogenous Phobos materials should contain high-temperature phases with the bulk chemistry possibly representing a mixture of Martian silicate reservoirs (crust and mantle) and the impactor. In addition to such contrasting characteristics of the endogenous Phobos materials, stable isotopic systematics of O, Cr, and Ti will further differentiate the source of Phobos’ building blocks. The exogenous late accreted materials are expected to contain Mars-originating materials. Because the Mars-originating materials could be derived from several geologic units on the surface of Mars by random samplings through impacts, which could be potentially corroborated by radiometric dating of the returned samples, they would provide valuable information about the change in surface environments through the history of Mars.

References

C.B. Agee et al., Unique meteorite from early Amazonian Mars: water-rich basaltic breccia Northwest Africa 7034. Science 339, 780–785 (2013)

C.M.O.D. Alexander et al., The provenances of asteroids, and their contributions to the volatile inventories of the terrestrial planets. Science 337, 721–723 (2012)

Y. Amelin et al., Lead isotopic ages of chondrules and calcium-aluminium-rich inclusions. Science 297, 1678–1683 (2002)

G.A. Avanesov et al., Television observations of Phobos. Nature 341, 585–587 (1989)

D. Banfield, Mars Science Goals, Objectives, Investigations, and Priorities: 2018 Version, Mars Exploration Program Analysis Group (MEPAG) (2018). https://mepag.jpl.nasa.gov/reports/MEPAG%20Goals_Document_2018.pdf

A. Basilevsky et al., The surface geology and geomorphology of Phobos. Planet. Space Sci. 102, 95–118 (2014)

D.W. Beaty et al., The potential science and engineering value of samples delivered to Earth by Mars sample return: international MSR Objectives and Samples Team (iMOST). Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 54, S3–S152 (2019)

J.-P. Bibring et al., ISM observations of Mars and PHOBOS-first results, in Lunar and Planetary Science Conference Proceedings, vol. 20 (1990), pp. 461–471

J.P. Bibring et al., Global mineralogical and aqueous mars history derived from OMEGA/Mars express data. Science 312, 400–404 (2006)

L.E. Borg et al., Constraints on the U-Pb isotopic systematics of Mars inferred from a combined U-Pb, Rb-Sr, and Sm-Nd isotopic study of the Martian meteorite Zagami. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 69, 5819–5830 (2005)

A.J. Brearley, Chondritic meteorites, in Planetary Materials (1998)

D. Brownlee et al., Comet 81P/Wild 2 under a microscope. Science 314, 1711–1716 (2006)

B.A. Cantor et al., Phobos disk-integrated photometry: 1994–1997 HST observations. Icarus 142, 414–420 (1999)

M.H. Carr, The Surface of Mars (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2006)

J.M. Day et al., Highly siderophile elements in Earth, Mars, the Moon, and asteroids. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 81, 161–238 (2016)

G. Dreibus, H. Wanke, Mars, a volatile-rich planet. Meteoritics 20, 367–381 (1985)

J. Dworkin et al., OSIRIS-REx contamination control strategy and implementation. Space Sci. Rev. 214, 19 (2018)

B.L. Ehlmann, C.S. Edwards, Mineralogy of the Martian surface. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 42, 291–315 (2014)

B. Ehlmann et al., The sustainability of habitability on terrestrial planets: insights, questions, and needed measurements from Mars for understanding the evolution of Earth-like worlds. J. Geophys. Res., Planets 121, 1927–1961 (2016)

J.L. Eigenbrode et al., Organic matter preserved in 3-billion-year-old mudstones at Gale crater, Mars. Science 360, 1096–1101 (2018)

J. Farquhar, M.H. Thiemens, Oxygen cycle of the Martian atmosphere-regolith system: \(\Delta ^{17}\)O of secondary phases in Nakhla and Lafayette. J. Geophys. Res., Planets 105, 11991–11997 (2000)

A. Fraeman et al., Analysis of disk-resolved OMEGA and CRISM spectral observations of Phobos and Deimos. J. Geophys. Res., Planets 117, E00J15 (2012)

A. Fraeman et al., Spectral absorptions on Phobos and Deimos in the visible/near infrared wavelengths and their compositional constraints. Icarus 229, 196–205 (2014)

K. Fujita et al., Assessment of the probability of microbial contamination for sample return from Martian moons I: departure of microbes from Martian surface. Life Sci. Space Res. 23, 73–84 (2019)

A. Fujiwara et al., The rubble-pile asteroid Itokawa as observed by Hayabusa. Science 312, 1330–1334 (2006)

W. Fujiya et al., Evidence for the late formation of hydrous asteroids from young meteoritic carbonates. Nat. Commun. 3, 627 (2012)

W. Fujiya et al., Migration of D-type asteroids from the outer Solar System inferred from carbonate in meteorites. Nat. Astron. 3, 910–915 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-019-0801-4

I. Halevy et al., Carbonates in the Martian meteorite Allan Hills 84001 formed at \(18\pm 4\) C in a near-surface aqueous environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 16895–16899 (2011)

W.K. Hartmann, Additional evidence about an early intense flux of C asteroids and the origin of Phobos. Icarus 87, 236–240 (1990)

A.J. Hesselbrock, D.A. Minton, An ongoing satellite–ring cycle of Mars and the origins of Phobos and Deimos. Nat. Geosci. 10, 266 (2017)

A. Higuchi et al., Temporary capture of asteroids by an eccentric planet. Astrophys. J. 153, 155 (2017)

R. Hyodo et al., On the impact origin of Phobos and Deimos. I. Thermodynamic and physical aspects. Astrophys. J. 845, 125 (2017)

R. Hyodo et al., Transport of impact ejecta from Mars to its moons as a means to reveal Martian history. Sci. Rep. 9, 19833 (2019)

S. Kameda et al., Telescopic Camera (TENGOO) and Wide-Angle Multiband Camera (OROCHI) Onboard Martian Moons eXploration (MMX) Spacecraft, in The 50th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2019). Abstract #2292

J. Karner et al., Olivine from planetary basalts: chemical signatures that indicate planetary parentage and those that record igneous setting and process. Am. Mineral. 88, 806–816 (2003)

J. Karner et al., Comparative planetary mineralogy: pyroxene major- and minor-element chemistry and partitioning of vanadium between pyroxene and melt in planetary basalts. Am. Mineral. 91, 1574–1582 (2006)

Y. Kawakatsu et al., Mission Concept of Martian moons exploration (MMX), in Proceedings in the 68th International Astronautical Congress. IAC-17-A3.3A.5 (2017). http://www.iafastro.org/events/iac/iac-2017/

Y. Kawakatsu et al., Mission design of Martian Moons eXploration (MMX), in 70th International Astronautical Congress. IAC-18-A3.3A.8 (2019). http://www.iafastro.org/events/iac/iac-2019/

N.T. Kita et al., High precision SIMS oxygen three isotope study of chondrules in LL3 chondrites: role of ambient gas during chondrule formation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 6610–6635 (2010)

F. Kitajima et al., A micro-Raman and infrared study of several Hayabusa category 3 (organic) particles. Earth Planets Space 67, 20 (2015)

T. Kleine et al., Rapid accretion and early core formation on asteroids and the terrestrial planets from Hf-W chronometry. Nature 418, 952–955 (2002)

G. Kminek et al., Amino acids in the Tagish Lake meteorite. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 37, 697–701 (2002)

M. Kobayashi et al., In situ observations of dust particles in Martian dust belts using a large-sensitive-area dust sensor. Planet. Space Sci. 156, 41–46 (2018)

A. Krot et al., Sources of water and aqueous activity on the chondrite parent asteroids, in Asteroids IV (2015), pp. 635–660

T. Kruijer et al., Protracted core formation and rapid accretion of protoplanets. Science 344, 1150–1154 (2014)

T.S. Kruijer et al., Age of Jupiter inferred from the distinct genetics and formation times of meteorites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114, 6712–6716 (2017)

K. Kuramoto et al., Martian Moons Exploration (MMX) conceptual study update, in The 49th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2018). Abstract #2143

K. Kurosawa et al., Assessment of the probability of microbial contamination for sample return from Martian moons II: the fate of microbes on Martian moons. Life Sci. Space Res. 23, 85–100 (2019)

T.J. Lapen et al., A younger age for ALH84001 and its geochemical link to shergottite sources in Mars. Science 328, 347–351 (2010)

D.S. Lauretta et al., The unexpected surface of asteroid (101955) Bennu. Nature 568, 55–60 (2019)

D.J. Lawrence et al., Measuring the elemental composition of Phobos: the Mars-moon exploration with GAmma rays and NEutrons investigation for the Martian moons eXploration mission. Earth Space Sci. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EA000811

L.A. Leshin et al., Hydrogen isotope geochemistry of SNC meteorites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 60, 2635–2650 (1996)

B. Marty, The origins and concentrations of water, carbon, nitrogen and noble gases on Earth. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 313–314, 56–66 (2012)

F.M. McCubbin et al., Is Mercury a volatile-rich planet? Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L09202 (2012)

H.Y. McSween, Petrology on Mars. Am. Mineral. 100, 2380–2395 (2015)

H.Y. McSween, A.H. Treiman, Martian meteorites, in Planetary Materials, vol. 36, ed. by J.J. Papike (Mineralogical Society of America, Washington, 1998), p. 53

H.Y. McSween et al., Elemental composition of the Martian crust. Science 324, 736–739 (2009)

D.W. Mittlefehldt et al., Non-chondritic meteorites from asteroidal bodies, in Planetary Materials, vol. 36, ed. by J.J. Papike (Mineralogical Society of America, Washington, 1998), pp. 1–195

S. Murchie, S. Erard, Spectral properties and heterogeneity of Phobos from measurements by Phobos 2. Icarus 123, 63–86 (1996)

S.L. Murchie et al., The value of Phobos sample return. Planet. Space Sci. 102, 176–182 (2014)

M. Nayak et al., Effects of mass transfer between Martian satellites on surface geology. Icarus 267, 220–231 (2016)

R. Okazaki et al., Hayabusa2 sample catcher and container: metal-seal system for vacuum encapsulation of returned samples with volatiles and organic compounds recovered from C-type asteroid Ryugu. Space Sci. Rev. 208, 107–124 (2017)

S. Pizzarello et al., The organic content of the Tagish Lake meteorite. Science 293, 2236–2239 (2001)

L. Qin et al., Contributors to chromium isotope variation of meteorites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 1122–1145 (2010)

K.R. Ramsley, J.W. Head, Mars impact ejecta in the regolith of Phobos: bulk concentration and distribution. Planet. Space Sci. 87, 115–129 (2013)

P. Rosenblatt et al., Accretion of Phobos and Deimos in an extended debris disc stirred by transient moons. Nat. Geosci. 9, 581–583 (2016)

V. Safronov et al., Protosatellite swarms, in Satellites (University of Arizona Press, Tucson, 1986), pp. 89–116

H. Sawada et al., Hayabusa2 sampler: collection of asteroidal surface material. Space Sci. Rev. 208, 81–106 (2017)

D.P. Simonelli et al., Photometric properties of Phobos surface materials from Viking images. Icarus 131, 52–77 (1998)

H. Sugahara et al., Amino acids on witness coupons collected from the ISAS/JAXA curation facility for the assessment and quality control of the Hayabusa2 sampling procedure. Earth Planets Space 70, 194 (2018)

S. Tachibana et al., Hayabusa2: scientific importance of samples returned from C-type near-Earth asteroid (162173) 1999 JU3. Geochem. J. 48, 571–587 (2014)

G.J. Taylor, The bulk composition of Mars. Chem. Erde 73, 401–420 (2013)

S.R. Taylor et al., Earth-moon system, planetary science, and lessons learned. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 60, 657–704 (2006)

N. Thomas et al., Spectral heterogeneity on Phobos and Deimos: HiRISE observations and comparisons to Mars Pathfinder results. Planet. Space Sci. 59, 1281–1292 (2011)

A. Trinquier et al., Widespread 54Cr heterogeneity in the inner solar system. Astrophys. J. 655, 1179 (2007)

A. Trinquier et al., Mn-53-Cr-53 systematics of the early Solar System revisited. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 72, 5146–5163 (2008)

A. Trinquier et al., Origin of nucleosynthetic isotope heterogeneity in the solar protoplanetary disk. Science 324, 374–376 (2009)

S. Ulamec et al., A rover for the JAXA MMX Mission to Phobos, in 70th International Astronautical Congress. IAC-19-A3.4.B8 (2019). http://www.iafastro.org/events/iac/iac-2019/

T. Usui, What geology and mineralogy tell us about water on Mars, in Astrobiology (Springer, Berlin, 2019), pp. 345–352

T. Usui et al., Origin of water and mantle–crust interactions on Mars inferred from hydrogen isotopes and volatile element abundances of olivine-hosted melt inclusions of primitive shergottites. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 357–358, 119–129 (2012)

T. Usui et al., Meteoritic evidence for a previously unrecognized hydrogen reservoir on Mars. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 410, 140–151 (2015)

T. Usui et al., Martian Moons eXploration (MMX): Japanese Phobos Sample Return Mission, in 42nd COSPAR Scientific Assembly, Pasadena, California, USA (2018). http://cospar2018.org/

P.H. Warren, Stable-isotopic anomalies and the accretionary assemblage of the Earth and Mars: a subordinate role for carbonaceous chondrites. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 311, 93–100 (2011)

S. Watanabe et al., Hayabusa2 arrives at the carbonaceous asteroid 162173 Ryugu—a spinning top–shaped rubble pile. Science 364, 268–272 (2019)

C.R. Webster et al., Low upper limit to methane abundance on Mars. Science 342, 355–357 (2013)

H. Yabuta et al., X-ray absorption near edge structure spectroscopic study of Hayabusa category 3 carbonaceous particles. Earth Planets Space 66, 156 (2014)

H. Yurimoto et al., Oxygen isotopic compositions of asteroidal materials returned from Itokawa by the Hayabusa mission. Science 333, 1116–1119 (2011)

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to B. Marty, H.Y. McSween, and an anonymous reviewer for constructive reviews and M. Anand for editorial handling. We thank the MMX Science Board and the MMX study team for insightful discussions for this project. We also thank M. Zolensky, P. Mitchel, and N. Chabot for comments on the early version of this manuscript, and R. Fukai for compiling meteorite data used in Fig. 2. Our work was supported by ISAS/JAXA as a part of Phase-A activity of MMX and by a Grant-in-Aid from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science to TU (17H06459, 15KK0153). TU gives special thanks to Europlanet for the opportunity to present our work at the ISSI workshop “Role of Sample Return in Addressing Major Outstanding Questions in Planetary Sciences”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Role of Sample Return in Addressing Major Questions in Planetary Sciences

Edited by Mahesh Anand, Sara Russell, Yangting Lin, Meenakshi Wadhwa, Kuljeet Kaur Marhas and Shogo Tachibana

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Usui, T., Bajo, Ki., Fujiya, W. et al. The Importance of Phobos Sample Return for Understanding the Mars-Moon System. Space Sci Rev 216, 49 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-020-00668-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-020-00668-9