Abstract

Background

Cucumber is one of the most popular vegetables, and have little tolerance for water stress. The antioxidant defense system is one of major drought defense and adaptive mechanisms in plants, however, relatively few data are available regarding antioxidant systems in responses of cucumber to water deficit. The effect of short-term drought stress on the antioxidant system, lipid peroxidation and water content in cucumber seedlings roots was investigated.

Results

The results showed that polyethylene glycol (PEG) induced water stress markedly decreased water content of cucumber seedling roots after treatment of 36 h, and caused excessive generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) including superoxide (O2.−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Meanwhile, malondialdehyde (MDA) content increased. Antioxidant enzymes including superoxide dismutases (SOD), peroxidases (POD), catalase (CAT) and ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activities increased in different time and different extent under water stress, while ascorbate (AsA) and glutathione (GSH) content, glutathione reductase (GR), dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR) and monodehydroascorbate reductase (MDHAR) activities all decreased when compared to control.

Conclusions

Therefore, it can be concluded that water stress strongly disrupted the normal metabolism of roots and restrained water absorption, and seemingly enzymatic system played more important roles in protecting cucumber seedling roots against oxidative damage than non-enzymatic system in short-term water deficit stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Water deficit is a major environmental factor restricting plant growth, development and productivity, particularly in arid regions more than any other single environmental factor. It seems the worldwide losses in crop yields from water deficit probably exceed the cumulative loss of all other stresses (Kramer [1983]). Seasonal drought is becoming a severe challenge in agriculture production in the Yangtze River Basin in China. It usually happens from June to August when is critical time for most crops, even worse, it tends to come along with high temperature (Huang et al. [2013]). It is well known that drought stress impairs numerous metabolic and physiological processes in plants (Mahajan and Tuteja [2005]). Water stress results in significant declines in water potential and relative water content (RWC) and directly affects many aspects of plant physiology (Correia et al. [2006]). Drought could induce excessive generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) including superoxide anion (O2.−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and hydroxyl radical (HO−), which could cause deterioration of membrane lipids, proteins and nucleic acids, leading to increased membrane leakage of solutes (Huang et al. [2013]; Shehab et al. [2010]). Thus, oxidative stress is one of the major causes of cellular damage in plants during stress (Miller et al. [2010]). However, to remove ROS and maintain redox homeostasis, plants have evolved a complex array of antioxidant defense systems to prevent oxidative injury resulting from high levels of ROS, which includes antioxidative enzymes superoxide dismutases (SOD), peroxidases (POD), catalase (CAT), glutathione reductase (GR) and ascorbate peroxidase (APX), dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR), and monodehydroascorbate reductase (MDHAR) (Asada [2006]), low molecular mass antioxidants ascorbate (AsA), glutathione (GSH), and some compatible solutes such as betaines and proline (Foyer and Noctor [2005]; Veljovic-Jovanovic et al. [2006]). Previous studies have shown that drought tolerant cultivars generally have enhanced constitutive antioxidant enzyme activity under drought stress in comparison with sensitive cultivars (Sun et al. [2013]). Maintaining a higher level of antioxidative enzyme activities may contribute to drought induction by increasing the capacity against oxidative damage (Sharma and Dubey [2005]).

Cucumber is one of the most popular vegetables, and it is considered a shallow-rooted crop and has been reported to have little tolerance for water stress. The antioxidant defense system is one of major drought defense and adaptive mechanisms in plants (An and Liang [2013]). To the best of our knowledge, however, relatively few data are available regarding antioxidant systems in responses of cucumber to water deficit. Therefore, in the present study, we investigated the effect of water deficit on antioxidant systems of cucumber seedlings.

Methods

Plant material and treatments

The experiments were carried out in the environment-controlled greenhouse. Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L., cv. Jinyou No. 1) seeds were placed in sterile Petri plates on filter paper moistened with distilled water. They were allowed to germinate in the dark in a thermostatically-controlled chamber at 29 ± 1°C for approximately 30 h. The germinated seeds were sown in 50 cells plug trays containing peat moss and perlite (1:1, v/v) at 1200 μmol m−2 s−1 photosynthetic photo flux density and 14/10 h (25–30/16–20°C) day/night regime. Relative humidity fluctuated between 60 and 75%. At the two-leaf stage, seedlings were removed from the plastic plates, and the roots were rinsed with distilled water. Uniformly sized healthy seedlings were selected and transferred into troughs (40 × 30 × 13 cm) filled with 10 L of full-strength Hoagland’s nutrient solution, which was aerated for 40 min each hour. After pre-culturing for 3 d, the seedlings were treated with the following methods: (1) control [CK (full-strength Hoagland’s nutrient solution)]; (2) 5% polyethylene glycol 6000 (PEG) treatment [5% PEG (full-strength Hoagland’s nutrient solution containing 5% PEG)]; (3) 10% PEG treatment [10% PEG (full-strength Hoagland’s nutrient solution containing 10% PEG)]; each treatment has nine containers, and each container includes 6 plants, providing a total of 54 plants per treatment. Root samples of CK and 10% PEG treatment were harvested in triplicate at 0, 12, 24 and 36 h after the treatment initiation and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C for the subsequent analyses. After 36 h of treatment, plant roots per treatment were collected for the determination of water content (WC).

Determination of WC of root

Roots of cucumber seedlings were washed with tap water two to three times, rinsed twice with distilled water, gently blotted dry with a paper towel, and weighed for fresh weight. Oven dried at 70°C to constant dry weight. WC of roots was calculated according to the formula WC = [(Fresh weight-dry weight)/ Fresh weight] × 100%.

Enzyme extraction and assays

For the enzyme assays, 0.3 g roots were ground with 2 mL ice-cold 25 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.8) containing 0.2 mM EDTA, 2 mM ascorbate and 2% PVP. The homogenates were centrifuged at 4°C for 20 min at 12,000 × g and the supernatant was used for enzyme activity assay. All steps in the preparation of the enzyme extract were carried out at 4°C. SOD activity assay was based on the method described by Giannopotitis and Ries ([1977]). POD activity was measured using modification of the procedure of Egley et al. ([1983]) , the reaction mixture in a total volume of 2 mL contained 25 mM (pH 7.0) sodium phosphate buffer, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.05% guaiacol (2-ethoxyphenol), 1.0 mM H2O2 and 100 μL enzymes extract. The increase of absorbance due to oxidation of guaiacol was measured at 470 nm. APX activity was determined according to Nakano and Asada ([1981]). CAT activity was done according to Cakmak and Marschner ([1992]). GR activity was measured as a decrease in A340 due to oxidation of NADPH according to Foyer and Halliwell ([1976]). MDHAR activity was determined following Hossain et al. ([1984]) with slight modification. The reaction mixture contained 50 mM of Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.5), 1 mM of NADH, 5 mM of ascorbic acid, 0.15 U of ascorbate oxidase and 30 μL of enzymes extract. The activity was calculated from the change in absorbance at A340 for 2 min when the extinction coefficient was 6.2 mM−1 cm−1. DHAR activity was determined following Nakano and Asada ([1981]) with some modifications. The reaction mixture contained 50 mM of KH2PO4 buffer (pH 7.0), 50 mM of GSH, 10 mM of DHA and 50 μL of enzyme extract. The activity was calculated from the change in absorbance at A265 for 2 min when the extinction coefficient was 14 mM−1 cm−1.

Determination of free radical production

The O2.− production rate was measured according to Elstner and Heupel ([1976]) by monitoring the nitrite formation from hydroxylamine in the presence of O2.−, with some modifications. One g root segments was homogenized with 3 mL of 65 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.8), 0.1 mL of 10 mM hydroxylamine hydrochloride, and 1 mL supernatant. After incubation at 25°C for 20 min, ethyl ether in the same volume was added and centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 5 min. A standard curve with NO2− was used to calculate the production rate of O2.− from the chemical reaction of O2.− and hydroxylamine. H2O2 content was measured by the titanium method (Patterson et al. [1984]). MDA content was measured by the thiobarbituric acid reaction method (Heath and Packer [1968]).

Assay of antioxidants

AsA content was measured in extracts according to the method of Jiang and Zhang ([2001]). GSH content was determined as described by Griffith ([1980]).

Statistical analysis

All data presented are the mean values. All experiments were conducted using three replicates at least. All data were statistically analyzed by the analysis of variance (ANOVA) with SAS software (SAS Institute, Cary, United States) using Duncan’s multiple range test at the 0.05 level of significance.

Results and discussions

Water state and oxidative free radical production in the roots of cucumber seedlings subjected to a short term water stress

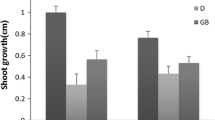

Drought stress reduces leaf size, stem extension and root proliferation, disturbs plant water relations and reduces water-use efficiency (Farooq et al. [2009]). In the present investigation, leaves of cucumber showed severely wilted appearance after 36 h under PEG treatment, and WC of roots was decreased dramatically (Figure 1).

Effect of water deficit stress on water content (WC) (%) of cucumber seedling roots. CK- control; 5% PEG- 5% polyethylene glycol 6000 (PEG) treatment; 10% PEG- 10% polyethylene glycol 6000 (PEG) treatment. Values represent the mean ± SE (n = 6). Letters indicate significant differences at P < 5% according to Duncan’s multiple range tests

Generation of ROS are common events during drought (Farooq et al. [2009]). Among ROS, H2O2, as a more stable ROS, can diffuse across biological membranes and severely damages plant metabolism under stress conditions (Ashraf [2009]). Here, the production rate of O2.− and H2O2 content both increased in the cucumber roots under water stress, especially after 36 h (Figure 2A and B). Membrane injury is a consequence of lipid peroxidation. Increasing MDA content is a good reflection of oxidative damage to membrane lipids. In drought-stressed plants, the MDA content increased, and was significantly higher than in the non-drought controls after 24 or 36 h (Figure 2C), indicating that the membrane was damaged by ROS and pronounced cell membrane peroxidation occurred under PEG-induced stress.

Effect of water deficit stress on free radical production and MDA content of cucumber seedling roots. A- O2.− production rate; B- H2O2 content; C- MDA content; CK- control; 10% PEG- 10% polyethylene glycol 6000 (PEG) treatment. Values represent the mean ± SE (n = 3). Letters indicate significant differences at P < 5% according to Duncan’s multiple range tests

The enzymatic antioxidation system in cucumber seedling roots in responses to a short term water stress

Antioxidative enzymes like SOD, POD and CAT play a significant role in conferring drought tolerance (Hameed et al. [2013]). In this study, compared with control, SOD activity increased markedly in cucumber seedling roots exposed to water stress at 12 h. An increase in SOD activity, which is commonly taken as an indicator of an increased ROS level. However, SOD activity was lower than the control after 24 h or 36 h and significant difference was found at 24 h of treatment (Figure 3A). The POD, CAT and APX activities exhibited increasing trends in response to drought stress (Figure 3B-3D). It is well known that APX and GR are the key enzymes participating in scavenging H2O2 within a cell via the Asada-Halliwell pathway (Foyer et al. [1994]). During the whole treatment period, the GR activity was lower than control under stress and there was apparent difference between water stress and control at 24 h, but thereafter no prominent decrease was observed after 36 h (Figure 3E). The promotion of antioxidant activity is probably a defense response. Nevertheless, as shown here and by others (Lee et al. [2009]), these enzymes usually did not match the increasing ROS production under severe drought stress.

Effect of water deficit stress on enzyme activity of cucumber seedling roots. A- SOD activity; B- POD activity; C- CAT activity; D- APX activity; E- GR activity; F- DHAR activity; G- MDHAR activity; CK- control; 10% PEG- 10% polyethylene glycol 6000 (PEG) treatment. Values represent the mean ± SE (n = 3). Letters indicate significant differences at P < 5% according to Duncan’s multiple range tests.

Responses of the non-enzymatic antioxidation systems in cucumber seedling roots to a short term water stress

The AsA-GSH cycle is one of the important protection systems against ROS in different cell compartments. Water stress led to a decrease of MDHAR activity within 24 h of treatment, but after 36 h, MDHAR activity under water stress was apparently higher than the control. DHAR activity had the similar trend with MDHAR activity (Figure 3F and G). Meanwhile, ASA and GSH content decreased under water stress (Figure 4A and B), which was one of reasons of the ROS accumulation in roots. Niu et al. ([2013]) stated that the ASA - deficient vtc1 mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana was more sensitive to drought stress than the wild - type. The low intrinsic ASA of the vct1 mutant decreased enzymatic antioxidant defense systems under drought stress. GR activity decreased was accompanied by a lower GSH content, suggesting that predominantly GSH oxidation took place under water stress. Similarly, drought induced oxidative stress in rice anthers leading to a PCD and pollen abortion along with down-regulation of antioxidants has been reported (Nguyen et al. [2009]). The decrease in the ASA and GSH content can be connected with disturbances of ASA and GSH biosynthesis, such as the decrease of MDHAR and DHAR activities. It can also be related to their oxidation in ROS scavenging cycles.

Effect of water deficit stress on antioxidants content of cucumber seedling roots. A- ASA content; B- GSH content; CK- control; 10% PEG- 10% polyethylene glycol 6000 (PEG) treatment. Values represent the mean ± SE (n = 3). Letters indicate significant differences at P < 5% according to Duncan’s multiple range tests.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present results suggested that water deficit interrupted the ROS balance between generation and elimination in cucumber roots, which strongly disrupted the normal metabolism of roots and restrained the water absorption. Finally, plants become wilted and their stems did not stand upright. Interestingly, we also found that the enzymatic system (SOD, POD, CAT and APX), partially, enhanced the ROS-scavenging capacity to some extent in short-term water deficit stress, while non-enzymatic system (ASA and GSH) exhibited a relative decease of ROS-scavenging in this experiment. Seemingly it showed that the enzymatic system played more important roles in protecting cucumber seedling roots against oxidative damage than non-enzymatic system in short-term water deficit stress. However, extended studies are needed to understand a precise mechanism.

Authors’contributions

LD and XW performed these experiments. HFF and CXD designed the research, analyzed data and wrote the paper. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Abbreviations

- APX:

-

Ascorbate peroxidase:

- AsA:

-

Ascorbic acid:

- CAT:

-

Catalase:

- DHAR:

-

Dehydroascorbate reductase:

- GR:

-

Glutathione reductase:

- GSH:

-

Reduced glutathione:

- H2O2:

-

Hydrogen peroxide:

- MDA:

-

Malondialdehyde:

- MDHAR:

-

Monodehydroascorbate reductase:

- O2.−:

-

Superoxide anion:

- POD:

-

Peroxidase:

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species:

- SOD:

-

Superoxide dismutase:

References

An YY, Liang ZS: Drought tolerance of Periploca sepium during seed germination: antioxidant defense and compatible solutes accumulation. Acta Physiol Plant 2013, 35: 959–967. 10.1007/s11738-012-1139-z

Asada K: Production and scavenging of reactive oxygen species in chloroplasts and their functions. Plant Physiol 2006, 141: 391–396. 10.1104/pp.106.082040

Ashraf M: Biotechnological approach of improving plant salt tolerance using antioxidants as markers. Biotechnol Adv 2009, 27: 84–93. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2008.09.003

Cakmak I, Marschner H: Magnesium deficiency and high light intensity enhance activities of superoxide dismutase, ascrobate peroxidase, and glutathione reductase in bean leaves. Plant Physiol 1992, 98: 1222–1227. 10.1104/pp.98.4.1222

Correia MJ, Osório ML, Osório J, Barrote I, Martins M, David MM: Influence of transient shade periods on the effects of drought on photosynthesis, carbohydrate accumulation and lipid peroxidation in sunflower leaves. Environ Exp Bot 2006, 58: 75–84. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2005.06.015

Egley GH, Paul RN, Vaughn KC, Duke SO: Role of peroxidase in the development of water-impermeable seed coats in Sida spinosa L. Planta 1983, 157: 224–232. 10.1007/BF00405186

Elstner EF, Heupel A: Inhibition of nitrate formation from hydroxylammoniumchloride: a simple assay for superoxide dismutase. Anal Biochem 1976, 70: 616–620. 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90488-7

Farooq M, Wahid A, Kobayashi N, Fujita D, Basra SMA: Plant drought stress: effects, mechanisms and management. Agron Sustain Dev 2009, 29: 185–212. 10.1051/agro:2008021

Foyer CH, Halliwell B: The presence of glutathione and glutathione reductase in chloroplasts: a proposed role in ascorbic acid metabolism. Planta 1976, 133: 21–25. 10.1007/BF00386001

Foyer CH, Lelandais M, Kunert KJ: Photooxidative stress in plants. Physiol Plant 1994, 92: 696–717. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1994.tb03042.x

Foyer CH, Noctor G: Oxidant and antioxidant signalling in plants: a re-evaluation of the concept of oxidative stress in a physiological context. Plant Cell Environ 2005, 28: 1056–1071. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01327.x

Giannopotitis CN, Ries SK: Superoxide dismutase in higher plants. Plant Physiol 1977, 59: 309–314. 10.1104/pp.59.2.309

Griffith OW: Determination of glutathione and glutathione disulfide using glutathione reductase and 2-vinylpyridine. Anal Biochem 1980, 106: 207–212. 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90139-6

Hameed A, Goher M, Iqbal N: Drought induced programmed cell death and associated changes in antioxidants, proteasea and lipid peroxidation in wheat leaves. Biol Plant 2013, 57: 370–374. 10.1007/s10535-012-0286-9

Heath RL, Packer L: Photoperoxidation in isolated chloroplasts. I. Kinetics and stoichiometry of fatty acid peroxidation. Arch Biochem Biophys 1968, 125: 189–198. 10.1016/0003-9861(68)90654-1

Hossain MA, Nakano Y, Asada K: Monodehydroascorbate reductase in spinach chloroplasts and its participation in the regeneration of ascorbate for scavenging hydrogen peroxide. Plant Cell Physiol 1984, 25: 385–395.

Huang CJ, Zhao SY, Wang LC, Anjum SA, Chen M, Zhou HF, Zou CM: Alteration in chlorophyll fluorescence, lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzymes activities in hybrid ramie ( Boehmeria nivea L.) under drought stress. Aust J Crop Sci 2013, 7: 594–599.

Jiang MY, Zhang JH: Effect of abscisic acid on active oxygen species, antioxidative defence system and oxidative damage in leaves of maize seedlings. Plant Cell Physiol 2001, 42: 1265–1273. 10.1093/pcp/pce162

Kramer PJ: Plant Water Relations. Academic Press, New York; 1983.

Lee BR, Li LS, Jung WJ, Jin YL, Avice JC, Ourry A, Kim TH: Water deficit-induced oxidative stress and the activation of antioxidant enzymes in white clover leaves. Biol Plant 2009, 53: 505–510. 10.1007/s10535-009-0091-2

Mahajan S, Tuteja N: Cold, salinity and drought stresses: An overview. Arch Biochem Biophys 2005, 444: 139–158. 10.1016/j.abb.2005.10.018

Miller G, Suzuki N, Ciftci-Yilmaz S, Mittler R: Reactive oxygen species homeostasis and signaling during drought and salinity stresses. Plant Cell Environ 2010, 33: 453–467. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02041.x

Nakano Y, Asada K: Hydrogen peroxide scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol 1981, 22: 867–880.

Nguyen GN, Hailstones DL, Wilkes M, Sutton BG: Drought-induced oxidative conditions in rice anthers leading to a programmed cell death and pollen abortion. J Agron Crop Sci 2009, 195: 157–164. 10.1111/j.1439-037X.2008.00357.x

Niu Y, Wang YP, Li P, Zhang F, Liu H, Zheng GC: Drought stress induces oxidative stress and the defense system in ascorbate - deficient vct1 mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana . Acta Physiol Plant 2013, 35: 1189–1200. 10.1007/s11738-012-1158-9

Patterson BD, MacRae EA, Ferguson IB: Estimation of hydrogen peroxide in plant extracts using titanium (IV). Anal Biochem 1984, 139: 487–492. 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90039-3

Sharma P, Dubey RS: Drought induces oxidative stress and enhances the activities of antioxidant enzymes in growing rice seedlings. Plant Growth Regul 2005, 46: 209–221. 10.1007/s10725-005-0002-2

Shehab GG, Ahmed OK, El-beltagi HS: Effects of various chemical agents for alleviation of drought stress in rice plants ( Oryza sativa L.). Not Bot Hort Agrobot Cluj 2010, 38: 139–148.

Sun J, Gu J, Zeng J, Han S, Song AP, Chen FD, Fang WM, Jiang JF, Chen SM: Changes in leaf morphology, antioxidant activity and photosynthesis capacity in two different drought-tolerant cultivars of chrysanthemum during and after water stress. Sci Hortic 2013, 161: 249–258. 10.1016/j.scienta.2013.07.015

Veljovic-Jovanovic S, Kukavica B, Stevanovic B, Navari-Izzo F: Senescence- and drought-related changes in peroxidase and superoxide dismutase isoforms in leaves of Ramonda serbica . J Exp Bot 2006, 57: 1759–1768. 10.1093/jxb/erl007

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31101539; No. 31201658).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests of this research.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, HF., Ding, L., Du, CX. et al. Effect of short-term water deficit stress on antioxidative systems in cucumber seedling roots. Bot Stud 55, 46 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40529-014-0046-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40529-014-0046-6