Abstract

TERT promoter (TERTp) mutations are found in the majority of World Health Organization (WHO) grade IV adult IDH wild-type glioblastoma (IDH-wt GBM). Here, we characterized the subset of IDH-wt GBMs that do not have TERTp mutations. In a cohort of 121 adult grade IV gliomas, we identified 109 IDH-wt GBMs, after excluding 11 IDH-mutant cases and one H3F3A -mutant case. Within the IDH-wt cases, 16 cases (14.7%) were TERTp wild-type (TERTp-wt). None of the 16 had BRAF V600E or H3F3A G34 hotspot mutations. When compared to TERTp mutants, patients with TERTp-wt GBMs, were significantly younger at first diagnosis (53.2 years vs. 60.7 years, p = 0.0096), and were more frequently found to have cerebellar location (p = 0.0027). Notably, 9 of 16 (56%) of TERTp-wt GBMs contained a PIK3CA or PIK3R1 mutation, while only 16/93 (17%) of TERTp-mutant GBMs harbored these alterations (p = 0.0018). As expected, 8/16 (50%) of TERTp-wt GBMs harbored mutations in the BAF complex gene family (ATRX, SMARCA4, SMARCB1, and ARID1A), compared with only 8/93 (9%) of TERTp-mutant GBMs (p = 0.0003). Mutations in BAF complex and PI3K pathway genes co-occurred more frequently in TERTp-wt GBMs (p = 0.0002), an association that has been observed in other cancers, suggesting a functional interaction indicative of a distinct pathway of gliomagenesis. Overall, our finding highlights heterogeneity within WHO-defined IDH wild-type GBMs and enrichment of the TERTp-wt subset for BAF/PI3K-altered tumors, potentially comprising a distinct clinical subtype of gliomas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most frequent and deadly primary brain tumor, accounting for approximately 45–50% of all primary malignant brain tumors [17, 18]. GBM is a heterogeneous entity, with a wide mutational spectrum. There has been an ever-increasing focus on molecular classification in GBM, to develop insights into the biology of this tumor and to subsequently improve diagnosis and treatment.

To emphasize the importance of molecular markers, the 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) revised neuropathological criteria identifies three categories of grade IV diffuse glioma. Two categories of GBM arise based on clustered genetic alterations, histologic variants, and clinical data [15], IDH wild-type and IDH mutant. An additional category of H3F3A K27 M mutant midline glioma has been designated grade IV, due the often poor prognosis of patients with these tumors. While IDH and H3F3A mutations identify gliomas with a distinct molecular origin, the remaining IDH wild-type subgroup of GBM, as it is defined currently, still contains significant heterogeneity. Emerging evidence indicates that TERT promoter (TERTp) mutations, which are common in these tumors, could additionally be useful clinically to classify IDH wild-type GBMs into subgroups with specific clinical courses [7, 12].

Here, we evaluated TERTp wild-type (TERTp-wt) GBMs to compare them to their TERTp mutant counterpart GBMs. We performed sequencing on a broad panel of genes and evaluated for the presence of fusions in a cohort of GBMs, to evaluate the mutational profile of TERTp-wt GBMs. In addition, we examined the clinical characteristics of this group.

Material and methods

The study was reviewed and approved by the human subjects’ institutional review boards of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Massachusetts General Hospital (P10–454) and complied with HIPAA guidelines. We retrospectively reviewed the genomic database at our institution for adult GBM cases submitted for genotyping using the SNaPshot panel version 2. Demographic, treatment and follow-up data were retrospectively collected.

SNaPshot next generation sequencing archer® FusionPlex®

Specimens were subjected to genomic analysis utilizing SNaPshot6, a hybrid capture based method for single nucleotide variant (SNV) and insertion/deletion (indel) detection in tumor DNA. SNaPshot targets 108 genetic loci frequently mutated in 15 cancer genes, including TERT promoter, IDH1/2, TP53, ATRX, PIK3CA, PIK3R1, NF1, and STAG2. The detailed list of all genes included in the SNaPshot v2 panel is shown in Additional file 1.

Archer® FusionPlex®

Extracted tumor RNA were interrogated for fusions by the Archer® FusionPlex® Solid Tumor (AK0034) kit [25]. This technology utilizes an anchored multiplex polymerase chain reaction (AMP) technique that detects gene rearrangements in a fusion partner agnostic manner. FASTQ data analysis, including fusion calling, was performed by ArcherDx Analysis software v5.0.6 using default parameters. The detailed list of all genes included in Archer® FusionPlex® is shown in Additional file 1.

MGMT promoter methylation

DNA was extracted from frozen tumor tissue and subjected to bisulfite treatment. Two separate methylation-specific PCR reactions were performed, one using primers specific for methylated MGMT promoter sequences, and a second using PCR primers specific for unmethylated MGMT promoter sequences [8].

ATRX immunohistochemistry methods

ATRX immunohistochemistry was preformed using ATRX Cat # BSB-3295 from Bio SB. RTU (ready to use) pretreatment ER2 (EDTA ph 9.0) for 15 min. The clone BSB-108 was used, as previously reported [21].

Statistical analysis

The statistical association of TERTp-wt GBM with other factors, including age, sex, other genomic alterations, and location of tumor, were analyzed using the Fisher exact test. The association of TERTp-wt GBM with ATRX immunohistochemistry, MGMT promoter methylation status, and presence of fusion gene by solid fusion panel were each also evaluated. Cases with unavailable molecular or IHC data were excluded from the final correlation analysis.

The data were analyzed using the Fisher exact test. Description of overall survival (OS) was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier product limit method. A two-tailed P value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Patient demographic and tumor characteristics

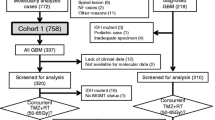

We identified 121 adult GBM cases with available molecular and immunohistochemistry data between 2016 and 2018 (Additional file 2). We excluded histologic GBMs containing IDH R132 and H3F3A mutations from statistical analyses (n = 11 and n = 1, respectively), for the reasons noted above [15].

Within this cohort (n = 109), the average age of patients was 60 years (range 18–84 years). Genetic alterations in the TERT gene were detected in 93 tumors; 92 were TERTp mutant (84.4%), and an additional case had a TERT-SUB fusion. The remaining 16 patients (14.7%) had TERTp-wt GBM (Fig. 1 and Additional file 2). The average age of patients with TERTp-wt GBMs was 53.2 years, which was significantly younger than the average age of their counterparts with TERTp mutant GBMs (60.7 years, p = 0.0096), and significantly older than the average age of patients with IDH mutant GBMs (38.6 years, p = 0.0041).

Across the cohort of IDH-wt GBM, the male to female ratio was 1.66. TERTp-wt GBMs did manifest a numerically higher proportion of male patients (13/16, 87.5%), compared with 55/93 male patients (59%) with TERTp mutant GBMs, but this difference was not statically significant (p = 0.103).

We examined the location of the primary tumor presentation. In the TERTp-wt group, the primary tumors were mainly found in a supratentorial (13) and thalamic/midline location (1), but also in a cerebellar site (3 cases). In contrast, in the TERTp mutant group, the tumors were exclusively located supratentorially (91) or thalamic/midline (2), with none found in the cerebellum. Consequently, a significant correlation between TERTp-wt status and cerebellar location (p = 0.0027) was observed. Of note, one of the cerebellar GBMs occurred in a patient with a NF1 germline mutation (Neurofibromatosis type 1).

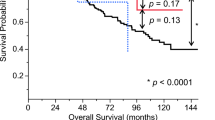

The median time of follow-up in surviving patients was 189 days for the TERTp-wt group and 246 days for the TERTp mutant group. Due to the short follow-up time, survival analyses may be underpowered to detect differences. Nonetheless, no detectable difference in survival was observed between the two groups (p = 0.74).

Genetic and epigenetic correlation

We examined genetic and epigenetic correlations between TERTp-wt versus mutant tumors. Four TERTp mutant cases were found to harbor a hotspot BRAF V600E mutation, which is characteristic of epithelioid GBM [14]. NF1 mutations were more commonly seen in TERTp-wt GBMs (6/16, 37.5%), in comparison with 18/93 (19%) in the TERTp mutant GBM cohort, however, this was not a statistically significant difference (p = 0.11). Also, we did not observe a significant difference in MGMT promoter methylation status in the TERTp-wt group vs. the mutant group (7/14 vs. 36/90, p = 0.56).

Activating alterations in the PI3K pathway (mainly PIK3CA or PIK3R1) were detected in 25 out of 109 cases in the cohort (23%) (Additional file 3). Interestingly, we observed a strong correlation between TERTp-wt status and mutations targeting the PI3K pathway: 9/16 (56%) of TERTp-wt GBMs contained a PI3K pathway alteration, while only 16/93 (17%) of mutant GBMs harbored these alterations (p = 0.0018) (Fig. 1). Furthermore, we detected an inverse correlation between PIK3CA/PIK3R1 and EGFR alterations. Only 2/25 cases (8%) with a PI3K pathway alteration had an EGFR mutation or EGFRvIII, whereas 38/82 of PI3K wild-type GBM had an EGFR alteration (46.3%, p = 0.0003).

Moreover, as expected, ATRX mutations were detected by sequencing in 6/16 (37.5%) TERTp-wt GBMs, while only 6/93 (6.5%) of TERTp mutant GBMs had an ATRX mutation. Consequently, this manifested as a significant correlation between TERTp-wt status and ATRX mutation (p = 0.0022). Of note, our workflow for assigning mutation was highly sensitive, leading to potential false positive assignments of ATRX candidate alterations that may not functionally inactivate the protein product. The further assessment of ATRX loss-of-expression using immunohistochemistry revealed a similarly significant result: 4/13 (31%) of TERTp-wt GBMs had ATRX loss vs. 0/80 mutant GBMs (p = 0.0002) (Fig. 2).

Finally, we noted that 8/16 (50%) of TERTp-wt GBMs harbored mutations in the BAF complex gene family (SMARCA4, SMARCB1, ATRX, and ARID1A), compared with only 8/93 of TERTp mutant GBMs (p = 0.0002). Given the role of ATRX in telomere maintenance, mutations in either group (ATRX vs SWI/SNF) may be unrelated. Nevertheless, we found that this association remained significant when excluding ATRX (3/16 (18.8%) of TERTp-wt GBMs harboring mutations compared with only 2/93 of TERTp mutant GBMs, p = 0.022). When combined with our analyses above, we detected a significant difference in co-occurrence between mutations in the BAF complex and PI3K pathway genes by comparing the TERTp-wt (n = 5/16) and TERTp mutant groups (n = 1/93, p = 0.0002) (Fig. 3).

Discussion

The WHO 2016 established an IDH wild-type subgroup of GBM, comprising the majority of adult grade IV gliomas, yet, this diagnostic grouping still contains significant heterogeneity. In an effort to better sub-classify IDH-wt GBMs, we used a broad panel of genes to genotype a large cohort of these neoplasms. In our analyses, we show that the TERTp-wt subgroup of IDH-wt GBM contains a distinct clinical and molecular profile.

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of extensive recent work studying adult high-grade gliomas. Over the last several years, a strong relationship has been demonstrated between mutational status and clinical, radiological, and molecular characteristics in adult diffuse gliomas [1, 2, 7]. Recently, Eckel-Passow et al. identified five main glioma molecular groups based on three alterations: 1p/19q co-deletion, and TERTp and IDH mutations. The groups had different ages of onset, survival, and associations with germline variants [7]. In addition, Aibaidula et al. specifically examined the adult IDH wild-type lower-grade gliomas, demonstrating significant heterogeneity within this group, with differences in prognosis based on further molecular classification by biomarkers such as TERTp mutation, EGFR amplification, H3F3A mutation, and MYB amplification [1]. Focusing on GBM, Arita et al. highlighted the importance of TERTp mutation, IDH mutation, and MGMT promoter methylation status on prognosis [2]. Furthermore, Stichel et al. demonstrated the potential of EGFR amplification, combined chromosome 7 gain and chromosome 10 loss, and TERTp mutations for classifying IDH wild-type GBM [24].

TERTp mutant GBMs show increased telomerase activation due to the increased TERT expression. In comparison, it is well-established that IDH mutant astrocytic gliomas often display the characteristic phenotype termed “alternative lengthening of telomeres” or ALT, associated with mutations in ATRX [10, 11, 13]. Another study that attempted to further sub-classify the 5 integrated WHO glioma groups by ATRX and TERT promoter status showed that ATRX alterations were enriched in TERTp-wt GBM [19]. A further study of the TERTp-wt subgroup by Diplas et al. identified SMARCAL1 as an additional mechanism of telomere maintenance within this subgroup [6].

In agreement with prior studies, we observed that TERTp-wt patients are significantly younger than their TERTp mutant counterparts [7] (Additional file 4). In addition, we identified a significantly higher rate of cerebellar GBM in the TERTp-wt compared with the TERTp mutant patients. Our finding is consistent with prior studies that have shown that cerebellar GBMs occur in patients that are younger than patients with supratentorial GBMs, and have decreased frequency in TERTp mutations and more frequent NF1 mutations [16, 20]. Taken together with our findings, these data support the proposal that cerebellar GBMs may comprise a distinct subclass of tumor, which may arise via an alternative molecular etiology when compared to supratentorial TERTp mutant GBM.

PI3K pathway alterations are frequently detected in gliomas, most commonly in grade IV lesions [4, 9]. Our data demonstrate that TERTp-wt GBMs are significantly enriched for PI3K pathway mutations compared with TERTp mutant GBM. Moreover, mutations in ARID1A and other components of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex (collectively known as the BAF complex), have been previously reported to be frequent in various cancer types (e.g. endometriosis-associated ovarian cancers, endometrial cancers and non-gynecological tumors) [3, 5, 22, 23]. Interestingly, in these cancers, alterations of gene encoding for components of the BAF complex frequently co-occur with activating mutations in PIK3CA [3, 23]. It has been additionally reported that dysregulation of the PI3K signaling pathway and loss of function of ARID1A may have a combination effect on tumor development [5, 22]. We speculate that this association may extend to a specific subset of gliomas, namely TERTp-wt GBM cases, which we find are enriched for BAF complex alterations and activating mutations in genes within the PI3K pathway. Following the logic of WHO 2016 classification, our findings suggest the potential definition of a molecular subtype of high-grade glioma, with implications for the utilization of targeted therapy in these patients [22].

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study identifies frequent PI3K pathway and BAF complex genetic alterations as co-occurring hallmarks of TERTp-wt GBM, potentially reflecting a unique molecular etiology of these tumors. If further validated, these findings may have significant implications for the sub-classification of IDH-wt GBM. Optimal management of these patients remains to be defined, but at a minimum, our data suggest that TERTp-mutant and TERTp-wt GBMs should be analyzed separately in future clinical studies, as they likely comprise distinct subclasses of neoplastic disease.

References

Aibaidula A, Chan AK, Shi Z, Li Y, Zhang R, Yang R et al (2017) Adult IDH wild-type lower-grade gliomas should be further stratified. Neuro-Oncology 19:1327–1337

Arita H, Yamasaki K, Matsushita Y, Nakamura T, Shimokawa A, Takami H et al (2016) A combination of TERT promoter mutation and MGMT methylation status predicts clinically relevant subgroups of newly diagnosed glioblastomas. Acta Neuropathol Commun 4:79

Bosse T, Ter Haar NT, Seeber LM, v Diest PJ, Hes FJ, Vasen HF et al (2013) Loss of ARID1A expression and its relationship with PI3K-Akt pathway alterations, TP53 and microsatellite instability in endometrial cancer. Mod Pathol 26:1525–1535

Broderick DK, Di C, Parrett TJ, Samuels YR, Cummins JM, McLendon RE et al (2004) Mutations of PIK3CA in anaplastic oligodendrogliomas, high-grade astrocytomas, and medulloblastomas. Cancer Res 64:5048–5050

Chandler RL, Damrauer JS, Raab JR, Schisler JC, Wilkerson MD, Didion JP et al (2015) Coexistent ARID1A-PIK3CA mutations promote ovarian clear-cell tumorigenesis through pro-tumorigenic inflammatory cytokine signalling. Nat Commun 6:6118

Diplas BH, He X, Brosnan-cashman JA, Liu H, Chen LH, Wang Z et al (2018) The genomic landscape of TERT promoter wildtype-IDH wildtype glioblastoma. Nat Commun 9:2087

Eckel-Passow JE, Lachance DH, Molinaro AM, Walsh KM, Decker PA, Sicotte H et al (2015) Glioma groups based on 1p/19q, IDH, and TERT promoter mutations in tumors. N Engl J Med 372:2499–2508

Esteller M, Garcia-Foncillas J, Andion E, Goodman SN, Hidalgo O, Vanaclocha V et al (2000) Inactivation of the DNA-repair gene MGMT and the clinical response of gliomas to alkylating agents. N Engl J Med 343:1350–1354

Gallia GL, Rand V, Siu IM, Eberhart CG, James CD, Marie SK et al (2006) PIK3CA gene mutations in pediatric and adult glioblastoma multiforme. Mol Cancer Res 4:709–714

Jiao Y, Killela PJ, Reitman ZJ, Rasheed AB, Heaphy CM, de Wilde RF et al (2012) Frequent ATRX, CIC, FUBP1 and IDH1 mutations refine the classification of malignant gliomas. Oncotarget 3:709–722

Kannan K, Inagaki A, Silber J, Gorovets D, Zhang J, Kastenhuber ER et al (2012) Whole-exome sequencing identifies ATRX mutation as a key molecular determinant in lower-grade glioma. Oncotarget 3:1194–1203

Killela PJ, Pirozzi CJ, Healy P, Reitman ZJ, Lipp E, Rasheed BA et al (2014) Mutations in IDH1, IDH2, and in the TERT promoter define clinically distinct subgroups of adult malignant gliomas. Oncotarget 5:1515–1525

Killela PJ, Reitman ZJ, Jiao Y, Bettegowda C, Agrawal N, Diaz LA Jr et al (2013) TERT promoter mutations occur frequently in gliomas and a subset of tumors derived from cells with low rates of self-renewal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:6021–6026

Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Aisner DL, Birks DK, Foreman NK (2013) Epithelioid GBMs show a high percentage of BRAF V600E mutation. Am J Surg Pathol 37:685–698

Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK et al (2016) The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol 131:803–820

Nomura M, Mukasa A, Nagae G, Yamamoto S, Tatsuno K, Ueda H et al (2017) Distinct molecular profile of diffuse cerebellar gliomas. Acta Neuropathol 134:941–956

Ohgaki H, Kleihues P (2005) Population-based studies on incidence, survival rates, and genetic alterations in astrocytic and oligodendroglial gliomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 64:479–489

Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Liao P, Rouse C, Chen Y, Dowling J et al (2014) CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2007-2011. Neuro Oncol 16(Suppl 4):iv1–i63

Pekmezci M, Rice T, Molinaro AM, Walsh KM, Decker PA, Hansen H et al (2017) Adult infiltrating gliomas with WHO 2016 integrated diagnosis: additional prognostic roles of ATRX and TERT. Acta Neuropathol 133:1001–1016

Picart T, Barritault M, Berthillier J, Meyronet D, Vasiljevic A, Frappaz D et al (2018) Characteristics of cerebellar glioblastomas in adults. J Neuro-Oncol 136:555–563

Reuss DE, Sahm F, Schrimpf D, Wiestler B, Capper D, Koelsche C et al (2015) ATRX and IDH1-R132H immunohistochemistry with subsequent copy number analysis and IDH sequencing as a basis for an "integrated" diagnostic approach for adult astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma and glioblastoma. Acta Neuropathol 129:133–146

Samartzis EP, Gutsche K, Dedes KJ, Fink D, Stucki M, Imesch P (2014) Loss of ARID1A expression sensitizes cancer cells to PI3K- and AKT-inhibition. Oncotarget 5:5295–5303

Samartzis EP, Noske A, Dedes KJ, Fink D, Imesch P (2013) ARID1A mutations and PI3K/AKT pathway alterations in endometriosis and endometriosis-associated ovarian carcinomas. Int J Mol Sci 14:18824–18849

Stichel D, Ebrahimi A, Reuss D, Schrimpf D, Ono T, Shirahata M et al (2018) Distribution of EGFR amplification, combined chromosome 7 gain and chromosome 10 loss, and TERT promoter mutation in brain tumors and their potential for the reclassification of IDHwt astrocytoma to glioblastoma. Acta Neuropathol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-018-1905-0

Zheng Z, Liebers M, Zhelyazkova B, Cao Y, Panditi D, Lynch K et al (2014) Anchored multiplex PCR for targeted next-generation sequencing. Nat Med 20:1479–1484

Funding

This work is supported by U.S. NIH T32 CA009216 (to Dr. E. Williams), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – Projektnummer: 401837860 (to Dr. T. Juratli) and by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award (to Dr. D. Cahill).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EAW carried out the research studies. EWA and AJI performed the sequence alignment. SST and TP participated in the sequence alignment. EAW, JJM, TAJ, and DPC designed the study. EAW and TAJ performed the statistical analysis. EAW, TAJ and DPC drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

A detailed list of all genes included in the SNaPshot v2 panel. (DOCX 14 kb)

Additional file 2:

A table including patients’ and tumor characteristics. (XLSX 20 kb)

Additional file 3:

A table listing all detected PI3K alterations in the cohort. The majority of alterations were reported in COSMIC (https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic/browse/genome) and/or occured at hospot locations in TumorPortal (http://www.tumorportal.org/). Reference human transcripts used: ENST00000263967.3 (PIK3CA) and ENST00000521381.1 (PIK3R1). (XLSX 11 kb)

Additional file 4:

Age distribution according to TERTp mutations. (TIF 462 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Williams, E.A., Miller, J.J., Tummala, S.S. et al. TERT promoter wild-type glioblastomas show distinct clinical features and frequent PI3K pathway mutations. acta neuropathol commun 6, 106 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-018-0613-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-018-0613-2