Abstract

Fluorine-containing compounds are widely used because they have properties required in textiles and coatings for electronic, automotive, and outdoor products. However, fluorinated compounds do not easily break down in nature, which has resulted in their accumulation in the environment as well as the human body. Recently, the enzymatic defluorination of fluorine-containing compounds has gained increasing attention. Here, we review the enzymatic defluorination reactions of fluorinated compounds. Furthermore, we review the enzyme engineering strategies for cleaving C–F bonds, which have the highest dissociation energy found in organic compounds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Because perfluorinated compounds (PFCs) repel both water and oil, they are used as durable repellent treatments for textiles such as outdoor clothes and for home products such as carpets [1]. In addition, PFCs are widely used in the production of fluoropolymers such as polytetrafluoroethylene (trade name, Teflon), which is widely used in coatings for electronic, automotive, and outdoor products [2].

However, PFCs are harmful to both the natural environment and humans as like other well-known pollutants [1, 3,4,5,6]. Furthermore, PFCs are persistent materials that do not readily break down in natural environments [2]. Some PFCs accumulate in the human body, leading to an increase over time of the residual concentration of PFCs in the blood and organs [7]. For these reasons, the biological decomposition of PFCs has gained increasing attention in recent times. The biological transformation of fluorotelomer alcohols (a type of PFC) was well summarized in several review papers [8, 9]. Nevertheless, the biological pathways underlying PFC decomposition, and the corresponding enzymes, have not been well elucidated.

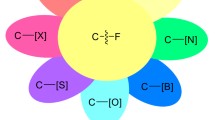

On the other hand, fluorinated compounds such as fluoroacetate and 5′-fluoro-5′-deoxyadenosine have been identified as natural products in nature [10, 11], demonstrating the existence of a biosynthesis pathway for fluorinated compounds in organisms [12]. A representative pathway of this type is the C–F bond forming reaction catalyzed by Streptomyces cattleya fluorinase, which converts inorganic NaF into fluorinated compounds [10, 13, 14]. Fluorinase, 5′-fluoro-5′-deoxyadenosine synthase, catalyzes the conversion of S-adenoxyl methionine to 5′-fluoro-5′-deoxyadenosine in S. cattleya (Fig. 1). In addition to our knowledge of the enzymes catalyzing fluorination reactions, previous studies have also identified enzymes involved in defluorination reactions [15,16,17,18,19].

Here, we review the defluorination reactions of aliphatic and aromatic compounds containing fluorine by native enzymes, including fluoroacetate dehalogenase, fluoroacetate-specific defluorinase, 4-fluorobenzoate dehalogenase, defluorinating enoyl-CoA hydratase/hydrolase, 4-fluorophenol monooxygenase, and peroxygenase-like LmbB2. Furthermore, we review recently developed enzyme engineering strategies for C–F bond cleavage, which give insights into the decomposition of fluorinated compounds. In this review, we do not discuss rarely studied enzymes involved in the biotransformation pathway, such as pyruvate dehydrogenase, maleylacetate reductase, and enol-lactone isomerase [20,21,22].

Defluorination by native enzymes

Fluoroacetate dehalogenase

Although the dissociation energy of C–F bond is among the highest found in nature, defluorination of fluoroacetate was identified in microorganisms, such as Burkholderia, Pseudomonas, Delftia, Rhodopseudomonas, and Moraxella [23,24,25,26]. The C–F bond on fluoroacetate can be cleaved by fluoroacetate dehalogenase in such microorganisms [15]. Fluoroacetate dehalogenase functions to the cleavage of C–Cl bond as well as C–F bond. Kinetic parameters (kcat and KM) of Burkholderia fluoroacetate dehalogenase have been known as 9.1 mM and 35 s−1 for fluoroacetate at 30 °C, while 15 mM and 1.5 s−1 for chloroacetate [27].

The first three dimensional structure of fluoroacetate dehalogenase was determined from Burkholderia sp. FA1 in 2009 [15]. The catalytic triad was identified as Asp104, His271, and Asp128 (Fig. 2). Carboxyl group of Asp104 was suggested as a nucleophile to attack the alpha carbon on fluoroacetate in an SN2 reaction. By this nucleophilic attack, fluoride ion is released from fluoroacetate, while enzyme–substrate (ES) ester intermediate is formed. In subsequent, the resulting ES ester intermediate is hydrolyzed by H2O which is the second nucleophile activated by His271. In a later study using quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical (QM/MM) calculations, it is revealed that two Arg residues at 105th and 108th positions are interacted with carboxyl group of fluoroacetate by hydrogen bond [28]. His149, Trp150, and Tyr212 stabilize fluorine atom via hydrogen bond, which results in reduction of activation energy [28].

The catalytic triad Asp104, His271, and Asp128 on fluoroacetate dehalogenase [15]

In terms of the substrate specificity of fluoroacetate dehalogenase, the importance of Trp150 was asserted by mutation of the amino acid residue [15]. The Trp150Phe mutation resulted in the complete loss of defluorination activity without the lack of dechlorination activity [15]. In a later study using docking simulation and QM/MM calculations, it was suggested that the conformational change for SN2 reaction is favorable in C–F bond rather than C–Cl bond [27, 29]. In the simulation, chloroacetate did not form the reactive conformation for SN2 reaction, because of the longer C–Cl bond [27]. In another study, crystal structures of a Rhodopseudomonas palustris fluoroacetate dehalogenase was determined along the defluorination reaction of fluoroacetate [30]. In such study, Chan and coworkers reported a halide pocket to support three hydrogen bonds which stabilize the fluoride ion in the fluoroacetate dehalogenase-mediated defluorination reaction [30]. Furthermore, the pocket is delicately balanced for fluorine, the smaller halogen atom, for the selectivity of fluoroacetate [30].

Fluoroacetate-specific defluorinase

Fluoroacetate-specific defluorinase has been identified in mammals that lives in area where plants capable of forming fluoroacetate grow [16]. These mammals detoxify fluoroacetate by fluoroacetate-specific defluorinase. Fluoroacetate-specific defluorinase has been purified from liver cytosol in mouse and rat [31, 32]. The defluorination mechanism of fluoroacetate-specific defluorinase is differ from that of fluoroacetate dehalogenase: glutathione is involved in the defluorination reaction by fluoroacetate-specific defluorinase (Fig. 3). Fluoroacetate-specific defluorinase showed similar characteristics to glutathione S-transferase (GST) theta and zeta classes in liver cytosol (GSTT and GSTZ, respectively) [33, 34].

The definition of fluoroacetate-specific defluorinase is still controversial. In a recent study, GSTZ (exactly GSTZ1C) has showed the highest fluoroacetate-specific defluorinase among all GST isozymes, which is just 3% of the total activity of fluoroacetate-specific defluorinase determined in cytosol [35]. Kinetic parameters (Vmax and KM) of fluoroacetate-specific defluorinase activity in rat cytosol have been reported as 27.7 mmol F−/mg protein/h and 3.8 mM for fluoroacetate [35]. In another study, novel fluoroacetate-specific defluorinase, FSD1 was isolated from rat hepatic cytosol [32]. FSD1 showed 81% of the total cytosolic activity of fluoroacetate-specific defluorinase, without GST activity [32]. FSD1 showed about 60% similarity to sorbitol dehydrogenase in amino acid sequence, although defluorination activity of sorbitol dehydrogenase has not been reported [32].

Enzymes involved in defluorination of fluorinated aromatics

Some enzymes are involved in the degradation pathway of aromatics: 4-fluorobenzoate dehalogenase, defluorinating enoyl-CoA hydratase/hydrolase, 4-fluorophenol monooxygenase, and peroxygenase-like LmbB2 (histidyl-ligated heme enzyme) for the degradation of fluorobenzoate, fluorophenol, fluorobenzene, and fluorotyrosine, respectively.

Defluorination of 4-fluorobenzoate and 2-fluorobenzoate is catalyzed by 4-fluorobenzoate dehalogenase [17] and defluorinating enoyl-CoA hydratase/hydrolase [18], respectively. However, the defluorination mechanism of two enzymes is quite differ from each other. In the reaction catalyzed by 4-fluorobenzoate dehalogenase, defluorination of 4-fluorobenzoate is directly conducted without the structural transformation, which was suggested by Oltmanns and coworkers [17]. The research group determined fluoride ion and trace amounts of 4-hydroxybenzoate, the apparent reaction product in the conversion reaction of 4-fluorobenzoate by using cell extracts of Aureobacterium sp. (Fig. 4) [17].

Defluorination reaction of 4-fluorobenzoate by 4-fluorobenzoate dehalogenase [17]

On the other hand, defluorination of 2-fluorobenzoate initiates with substrate activation to yield 2-fluorobenzoyl-CoA, which is further converted to F-1,5-dienoyl-CoA isomers [18]. By defluorinating enoyl-CoA hydratase/hydrolase (DCH/OAH), in the next step, two F-1,5-dienoyl-CoA isomers are hydrated to two different isomers including 6-F-6-OH-1-enoyl-CoA and 2-F-6-OH-1-enoyl-CoA (Fig. 5) [18]. This accompany the subsequent defluorination of unstable 6-F-6-OH-1-enoyl-CoA spontaneously to yield 6-oxo-1-enoyl-CoA by HF-expulsion. Stable 2-F-6-OH-1-enoyl-CoA is further hydrated by defluorinating enoyl-CoA hydrolase, to yield unstable 2-F-2,6-di-OH-cyclohexanoyl-CoA intermediate, which also spontaneously defluorinates to yield 2-oxo-6-OH-cyclohexanoyl-CoA (Fig. 5) [18].

Defluorination pathway of 2-fluorobenzoate [18]. BCR benzoyl-CoA reductase, DCH 5,5-dienoyl-CoA hydratase, OAH bifunctional 6-oxo-1-enoyl-CoA hydrolase

Defluorination of 4-fluorophenol is directly conducted without the structural transformation by 4-fluorophenol monooxygenase encoded from Arthrobacter sp. fpdA2 gene [19]. 4-Fluorophenol monooxygenase catalyzes NADPH-dependent hydroxylation and defluorination of 4-fluorophenol, together with flavin reductase encoded from the fpdB gene (Fig. 6) [19].

Defluorination reaction of 4-fluorophenol by 4-fluorophenol monooxygenase [19]

Enzyme catalyzing the direct defluorination of fluorobenzene has not been reported, yet. First, fluorobenzene is transformed to yield 3-fluoro-cis,cis-muconate through cascade reactions by three enzymes including fluorobenzene dioxygenase, fluorobenzene dihydrodiol dehydrogenase, and fluorocatechol 1,2-dioxygenase (Fig. 7) [36]. Then, defluorination of 3-fluoro-cis,cis-muconate conducts to yield cis-dienelactone by fluoromuconate cycloisomerase [36]. The other fate of 3-fluoro-cis,cis-muconate is the further conversion to yield 4-fluoromucono-lactone, which has been defluorinated into maleylacetate by trans-dienelactone hydrolase (Fig. 7) [36]. In addition, 4-fluoromucono-lactone could be defluorinated by spontaneous conversion to yield cis-dienelactone (Fig. 7).

Defluorination pathway of fluorobenzene [36]

Peroxygenase-like LmbB2 (histidyl-ligated heme enzyme) coded by the lmbB2 gene of the lincomycin biosynthesis gene cluster in Streptomyces lincolnensis catalyzes the defluorination of 3-fluorotyrosine to yield 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA) under the presence of H2O2 (Fig. 8) [37]. At the same time 3-fluoro-5-hydroxyl-l-tyrosine is also produced by oxidative C–H bond cleavage at C5 in the same reaction mediated by LmbB2 (Fig. 8) [37].

Defluorination of 3-fluorotyrosine by peroxygenase-like LmbB2, histidyl-ligated heme enzyme from Streptomyces lincolnensis [37]: a brief reaction, and b reaction mechanism

Enzymes engineering for C–F bond cleavage

Enzyme engineering is a powerful tool for providing new functions to the biological catalysts [38,39,40]. In a recent study, C–F bond cleavage by an engineered enzyme has been reported [41]. In this study, cysteine dioxygenase is engineered by replacing the tyrosine residue at 157th by 3,5-difluoro-tyrosine (Fig. 9a). Cysteine dioxygenase has a protein-derived cysteine–tyrosine cofactor (C–S thioester bond between Cys93 and Tyr157 in human) in the enzyme itself [41, 42]. The C–S thioester bond is formed by post-translational modification. The engineered cysteine dioxygenase catalyzed the defluorination of its own 3,5-difluoro-tyrosine residue at 157th during cofactor formation (Fig. 9b) [41].

Engineering of cysteine dioxygenase for C–F bond cleavage [41]. a 3,5-difluoro-tyrosine. b The cysteine–tyrosine cofactor derived from the defluorination of 3,5-difluoro-tyrosine residue at 157th during cofactor formation through post-translational modification

The C–F bonds have the highest dissociation energy found in organic compounds, which results in no ready breakdown of the substance containing the C–F bond in natural environments. For the reason, some PFCs had been considered as a serious organic pollutant in the Stockholm convention in 2006. Wide use of F-containing compounds has resulted in the widespread pollution in the world, which has been urging us to develop defluorination technologies for decompose the compounds. As described above, the enzymatic defluorination reactions of fluorinated compounds can be catalyzed by employing native and artificially designed enzymes. It is expected that more successful examples of C-F cleavage will appear through the enzyme engineering integrated with synthetic biology techniques. In the near future, native and artificial defluorination enzymes will play a major role in the reduction of the widely spread pollutant containing C–F bond.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Luo L, Kim M-J, Park J, Yang H-D, Kho Y, Chung M-S, Moon B (2019) Reduction of perfluorinated compound content in fish cake and swimming crab by different cooking methods. Appl Biol Chem 62:44

Grandjean P, Clapp R (2014) Changing interpretation of human health risks from perfluorinated compounds. Public Health Rep 129:482–485

Murphy CD, Clark BR, Amadio J (2009) Metabolism of fluoroorganic compounds in microorganisms: impacts for the environment and the production of fine chemicals. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 84:617

Choi G-H, Lee D-Y, Bae J-Y, Rho J-H, Moon B-C, Kim J-H (2018) Bioconcentration factor of perfluorochemicals for each aerial part of rice. J Appl Biol Chem 61:191–194

Ishag AESA, Abdelbagi AO, Hammad AMA, Elsheikh EAE, Elsaid OE, Hur J-H (2017) Biodegradation of endosulfan and pendimethalin by three strains of bacteria isolated from pesticides-polluted soils in the Sudan. Appl Biol Chem 60:287–297

Bulut H, Yıldırım Doğan N (2018) Determination by molecular methods of genetic and epigenetic changes caused by heavy metals released from thermal power plants. Appl Biol Chem 61:189–196

Sunderland EM, Hu XC, Dassuncao C, Tokranov AK, Wagner CC, Allen JG (2019) A review of the pathways of human exposure to poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and present understanding of health effects. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 29:131–147

Butt CM, Muir DC, Mabury SA (2014) Biotransformation pathways of fluorotelomer-based polyfluoroalkyl substances: a review. Environ Toxicol Chem 33:243–267

Young CJ, Mabury SA (2010) Atmospheric perfluorinated acid precursors: chemistry, occurrence, and impacts. Rev Environ Contam Toxicol 208:1–109

Zhao C, Li P, Deng Z, Ou H-Y, McGlinchey RP, O’Hagan D (2012) Insights into fluorometabolite biosynthesis in Streptomyces cattleya DSM46488 through genome sequence and knockout mutants. Bioorg Chem 44:1–7

O’Hagan D, Deng H (2015) Enzymatic fluorination and biotechnological developments of the fluorinase. Chem Rev 115:634–649

Walker MC, Wen M, Weeks AM, Chang MCY (2012) Temporal and fluoride control of secondary metabolism regulates cellular organofluorine biosynthesis. ACS Chem Biol 7:1576–1585

Deng H, O’Hagan D, Schaffrath C (2004) Fluorometabolite biosynthesis and the fluorinase from Streptomyces cattleya. Nat Prod Rep 21:773–784

O’Hagan D, Schaffrath C, Cobb SL, Hamilton JT, Murphy CD (2002) Biochemistry: biosynthesis of an organofluorine molecule. Nature 416:279

Jitsumori K, Omi R, Kurihara T, Kurata A, Mihara H, Miyahara I, Hirotsu K, Esaki N (2009) X-ray crystallographic and mutational studies of fluoroacetate dehalogenase from Burkholderia sp. strain FA1. J Bacteriol 191:2630–2637

Kostyniak PJ, Soiefer AI (1984) The role of fluoroacetate-specific dehalogenase and glutathione transferase in the metabolism of fluoroacetamide and 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene. Toxicol Lett 22:217–222

Oltmanns RH, Müller R, Otto MK, Lingens F (1989) Evidence for a new pathway in the bacterial degradation of 4-fluorobenzoate. Appl Environ Microbiol 55:2499–2504

Tiedt O, Mergelsberg M, Eisenreich W, Boll M (2017) Promiscuous defluorinating enoyl-CoA hydratases/hydrolases allow for complete anaerobic degradation of 2-fluorobenzoate. Front Microbiol 8:2579

Ferreira MIM, Iida T, Hasan SA, Nakamura K, Fraaije MW, Janssen DB, Kudo T (2009) Analysis of two gene clusters involved in the degradation of 4-fluorophenol by Arthrobacter sp. strain IF1. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:7767–7773

Natarajan R, Azerad R, Badet B, Copin E (2005) Microbial cleavage of CF bond. J Fluor Chem 126:424–435

Murphy CD (2010) Biodegradation and biotransformation of organofluorine compounds. Biotechnol Lett 32:351–359

Kiel M, Engesser K-H (2015) The biodegradation vs. biotransformation of fluorosubstituted aromatics. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 99:7433–7464

Goldman P (1965) The enzymatic cleavage of the carbon–fluorine bond in fluoroacetate. J Biol Chem 240:3434–3438

Kawasaki H, Yahara H, Tonomura K (1984) Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of the haloacetate dehalogenase genes from moraxella plasmid pUO1. Agric Biol Chem 48:2627–2632

Liu JQ, Kurihara T, Ichiyama S, Miyagi M, Tsunasawa S, Kawasaki H, Soda K, Esaki N (1998) Reaction mechanism of fluoroacetate dehalogenase from Moraxella sp. J Biol Chem 273:30897–30902

Verschueren KH, Seljee F, Rozeboom HJ, Kalk KH, Dijkstra BW (1993) Crystallographic analysis of the catalytic mechanism of haloalkane dehalogenase. Nature 363:693–698

Nakayama T, Kamachi T, Jitsumori K, Omi R, Hirotsu K, Esaki N, Kurihara T, Yoshizawa K (2012) Substrate specificity of fluoroacetate dehalogenase: an insight from crystallographic analysis, fluorescence spectroscopy, and theoretical computations. Chem Eur J 18:8392–8402

Kamachi T, Nakayama T, Shitamichi O, Jitsumori K, Kurihara T, Esaki N, Yoshizawa K (2009) The catalytic mechanism of fluoroacetate dehalogenase: a computational exploration of biological dehalogenation. Chemistry 15:7394–7403

Li Y, Zhang R, Du L, Zhang Q, Wang W (2016) Catalytic mechanism of C–F bond cleavage: insights from QM/MM analysis of fluoroacetate dehalogenase. Catal Sci Technol 6:73–80

Chan PW, Yakunin AF, Edwards EA, Pai EF (2011) Mapping the reaction coordinates of enzymatic defluorination. J Am Chem Soc 133:7461–7468

Soiefer AI, Kostyniak PJ (1984) Purification of a fluoroacetate-specific defluorinase from mouse liver cytosol. J Biol Chem 259:10787–10792

Tu LQ, Chen YY, Wright PFA, Rix CJ, Bolton-Grob R, Ahokas JT (2005) Characterization of the fluoroacetate detoxication enzymes of rat liver cytosol. Xenobiotica 35:989–1002

Meyer DJ, Coles B, Pemble SE, Gilmore KS, Fraser GM, Ketterer B (1991) Theta, a new class of glutathione transferases purified from rat and man. Biochem J 274(Pt 2):409–414

Board GP, Baker TR, Chelvanayagam G, Jermiin SL (1997) Zeta, a novel class of glutathione transferases in a range of species from plants to humans. Biochem J 328:929–935

Tu LQ, Wright PFA, Rix CJ, Ahokas JT (2006) Is fluoroacetate-specific defluorinase a glutathione S-transferase? Comp Biochem Phys C 143:59–66

Carvalho MF, Ferreira MIM, Moreira IS, Castro PML, Janssen DB (2006) Degradation of fluorobenzene by Rhizobiales strain f11 via ortho cleavage of 4-fluorocatechol and catechol. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:7413–7417

Wang Y, Davis I, Shin I, Wherritt DJ, Griffith WP, Dornevil K, Colabroy KL, Liu A (2019) Biocatalytic carbon–hydrogen and carbon–fluorine bond cleavage through hydroxylation promoted by a histidyl-ligated heme enzyme. ACS Catal 9:4764–4776

Byun S, Park HJ, Joo JC, Kim YH (2019) Enzymatic synthesis of d-pipecolic acid by engineering the substrate specificity of Trypanosoma cruzi proline racemase and its molecular docking study. Biotechnol Bioproc Eng 24:215–222

Maharjan A, Alkotaini B, Kim BS (2018) Fusion of carbohydrate binding modules to bifunctional cellulase to enhance binding affinity and cellulolytic activity. Biotechnol Bioproc Eng 23:79–85

Xu D, Zhao J, Cao G, Wang J, Li Q, Zheng P, Zhao S, Sun J (2018) Removal of feedback inhibition of Corynebacterium glutamicum phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase by addition of a short terminal peptide. Biotechnol Bioproc Eng 23:72–78

Li J, Griffith WP, Davis I, Shin I, Wang J, Li F, Wang Y, Wherritt DJ, Liu A (2018) Cleavage of a carbon-fluorine bond by an engineered cysteine dioxygenase. Nat Chem Biol 14:853–860

McCoy JG, Bailey LJ, Bitto E, Bingman CA, Aceti DJ, Fox BG, Phillips GN (2006) Structure and mechanism of mouse cysteine dioxygenase. PNAS USA 103:3084–3089

Acknowledgements

This study was carried out with the support of “Cooperative Research Program for Agricultural Science & Technology Development (Project No. PJ013321022019)”, Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea. YSJ was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT) through the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea (NRF-2019R1A4A1029125).

Funding

This study was carried out with the support of “Cooperative Research Program for Agricultural Science & Technology Development (Project No. PJ013321022019)”, Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea. YSJ was supported by a Grant from the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT) through the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea (NRF-2019R1A4A1029125).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YSJ and JHK designed the project. HJS, SWK, and YSJ wrote the manuscript. JHK and DCS revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Seong, H.J., Kwon, S.W., Seo, DC. et al. Enzymatic defluorination of fluorinated compounds. Appl Biol Chem 62, 62 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13765-019-0469-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13765-019-0469-6