Abstract

In this paper, a kind of fractional-order predator–prey (FOPP) model with a constant prey refuge and feedback control is considered. By analyzing characteristic equations, we carry out detailed discussion with respect to stability of equilibrium points of the considered FOPP model. Besides, the effects of prey refuge and feedback control are also studied by numerical analysis. Our study reveals that prey refuge and feedback control can be used to adjust the biomass of prey species and predator species such that prey species and predator species finally reach a better state level.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The investigation of the predator–prey model with prey refuge is an interesting and popular topic; here prey refuge can be reviewed as any strategy that decreases the risk of predation, including but not limited to burrows, prey aggregations, and heavy vegetation. Some eminent researchers [1–6] have studied the effects of prey refuge for integer-order predator–prey models and concluded that the prey refuge has a positive stabilizing effect on the predator–prey interaction, and prey individuals can be partially protected from predation. Ma [5] considered a kind of integer-order predator–prey system with a constant prey refuge, as follows:

where \(x(t)\) and \(y(t)\) are the respective population densities of the prey and predator at time t, and the parameters related to system (1) are positive. The author in [5] showed that if \(0< R< K-\frac{d}{e}\) is satisfied, then the unique positive equilibrium of model (1) is globally asymptotically stable; if \(R>K-\frac{d}{e}\) is satisfied, then the predator-extinction equilibrium of model (1) is locally asymptotically stable. Chen et al. [6] pointed out the proof in [5] was not perfect, and they derived sufficient criteria which ensure the global asymptotical stability of the positive equilibrium by employing the Lyapunov function method.

Fractional-order systems are not only an extension of conventional integer-order systems in mathematics but also have some merits that integer-order systems do not have, such as memory and hereditary properties [7, 8]. As is well known, many biological systems possesses memory [9]. Compared with integer-order systems, fractional-order systems can more accurately describe population models and reveal the relations between prey species and predator species [10–14]. In addition, fractional-order derivatives have been widely applied to several interdisciplinary fields [15–18]. In [10], Ahmed et al. considered a kind of fractional-order predator–prey (FOPP) system, as follows:

where \(0< q\leq1\), \({}_{0}^{c}D_{t}^{q}\) is the Caputo fractional-order derivative. The authors studied the local asymptotic stability of the equilibrium points.

Note that equilibrium value of the considered system is sometimes not the one we want, and maybe a smaller value is what we need in some situations [19]. In this case, we may change the system structurally by introducing a feedback control variable [20, 21], which can be implemented by employing biological control strategy. During the last decade, population models and epidemic models with feedback controls have been widely investigated; see [22–24] and the references cited therein. In [22–24], the authors showed that feedback controls have no influence on the permanence or global stability for the addressed systems. However, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, to this day, still no scholar has investigated the dynamic behavior of FOPP model with feedback control. Motivated by the above considerations, in this paper, we first consider the following FOPP model incorporating a constant prey refuge and feedback control:

where \(x(t)\) and \(y(t)\) are the respective population densities of the prey and predator at time t, \(u(t)\) denotes the feedback control variable for prey population at time t; r is the intrinsic growth rate of prey population, a is the intraspecific competition coefficient of prey population, b is the attack rate of predators to prey population, e is the efficiency of the predators converting consumed prey into new predator, d is the mortality rate of the predators, R denotes the quantity of hiding prey.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we introduce some notations, definitions and lemmas. In Sect. 3, we give the equilibrium points of FOPP model (3), and we discuss their stability. In Sect. 4, we present some key findings by numerical simulations. Finally, we give a conclusion in Sect. 5.

2 Preliminaries

We introduce some useful definitions and lemmas in this section, which are necessary for our latter study.

Definition 1

([7])

The fractional integral for a function ζ is defined as

where \(\Gamma(\cdot)\) is the well-known Gamma function, which is defined by \(\Gamma(z)=\int_{0}^{\infty}e^{-t}t^{z-1}\,dt\).

Definition 2

([7])

The Caputo fractional derivative for a function ζ is defined by

where n is a positive integer, \(n-1< q< n\). Particularly, when \(0< q<1\),

Lemma 1

([7])

If the Caputo fractional derivative \({}_{t_{0}}^{c}D_{t}^{q}\zeta(t)\) is integrable, then

Especially, for \(0< q\leq1\), one can obtain

Lemma 2

([25])

Let \(V(t)\) be a continuous function on \([0,+\infty)\) and satisfying

where \(0< q<1\) and θ is a constant. Then

Lemma 3

([26])

Consider the following fractional-order system:

where \(0< q<1\) and \(z\in\mathbb{R}^{n}\). The equilibrium points of system (4) can be calculated by solving the following equation: \(f(z)=0\). These points are locally asymptotically stable if all eigenvalues \(\lambda_{i}\) of the Jacobian matrix \(J=\frac{\partial f}{\partial z}\) evaluated at the equilibrium points satisfy the Matignon conditions:

The stable and unstable regions for \(0< q<1\) are shown in Fig. 1.

Stability region of the fractional-order system (4), where \(0< q\leq1\)

3 Equilibrium points and their stability

In this section, we study the asymptotic stability of the equilibrium points of system (3). For achieving equilibrium points of system (3), let

By a simple calculation, we list all possible equilibrium points:

-

(i)

For system (3) there always exists the trivial equilibrium point \(E_{0}(0,0,0)\).

-

(ii)

If \(rk>cm\) holds, then for system (3) there exists a predator-extinction equilibrium point \(E_{1}(x^{0},0,u^{0})\), where \(x^{0}=\frac {rk-cm}{ak}\), \(u^{0}=\frac{m(rk-cm)}{ak^{2}}\).

-

(iii)

If \(0< R<\frac{r}{a}-\frac{cm}{ak}-\frac{d}{e}\) holds, then for system (3) there exists a positive equilibrium point \(E_{2}(x^{*},y^{*},u^{*})\), where \(x^{*}=\frac{eR+d}{e}\), \(y^{*}=\frac {a(eR+d)(\frac{r}{a}-\frac{cm}{ak}-R-\frac{d}{e})}{bd}\), \(u^{*}=\frac {m(eR+d)}{ek}\).

In the following, we will discuss the stability properties of the equilibrium points \(E_{0}\), \(E_{1}\) and \(E_{2}\), respectively. At any equilibrium point \(E(x_{eq},y_{eq},u_{eq})\), the Jacobian matrix of system (3) is

Theorem 1

The trivial equilibrium point \(E_{0}\) of system (3) is locally asymptotically stable if either of the following criteria is satisfied:

- \((\mathrm{H}_{1})\) :

-

\(k\geq r\) and \(rk< cm\).

- \((\mathrm{H}_{2})\) :

-

\(k< r\), \(rk< cm\), \((k+r)^{2}<4cm\) and \(0< q<\frac {2}{\pi}\arctan(\frac{\sqrt{4(cm-rk)-(k-r)^{2}}}{r-k})\).

Proof

At \(E_{0}\), the Jacobian matrix of system (3) is

and the characteristic equation for \(J(E_{0})\) is

The eigenvalues of (7) are

Obviously, \(\lambda_{2}\) is always negative. Now we discuss the eigenvalues \(\lambda_{1}\) and \(\lambda_{3}\), it is clear that the cases \(k>r\), \(k=r\) and \(k< r\) are possible, so we consider three separate cases.

Case A. \(k>r\).

-

(ia)

\(rk< cm\). If \(\Delta_{1}\geq0\), we can derive from (8) that three eigenvalues \(\lambda _{1}\), \(\lambda_{2}\) and \(\lambda_{3}\) are negative, which imply that the equilibrium point \(E_{0}\) is locally asymptotically stable for all \(0< q<1\). In fact, \(\vert \arg(\lambda_{1,2,3}) \vert =\pi>\frac{q\pi}{2}\) for all \(0< q<1\), which satisfy the condition of Lemma 3. If \(\Delta_{1}<0\), then \(\lambda_{1}\) and \(\lambda_{3}\) are complex conjugates with negative real parts, which imply \(\vert \arg(\lambda _{1,3}) \vert =\arctan(\frac{\sqrt{-\Delta_{1}}}{r-k})+\pi>\frac{q\pi}{2}\) for all \(0< q<1\). According to Lemma 3, we know that the equilibrium point \(E_{0}\) is locally asymptotically stable.

-

(ib)

\(rk=cm\). From (7), we know that one eigenvalue must be zero and remaining two eigenvalues are negative. Then \(E_{0}\) is marginally stable.

-

(ic)

\(rk>cm\). Then \(\Delta_{1}=(k+r)^{2}-4cm>0\). From (8), we see that one of the eigenvalues \(\lambda_{1}\) and \(\lambda_{3}\) is positive and the other eigenvalue is negative. Let \(\lambda_{3}<0\) and \(\lambda _{1}>0\), which imply \(\vert \arg(\lambda_{3}) \vert =\pi>\frac{q\pi}{2}\) and \(\vert \arg (\lambda_{1}) \vert =0<\frac{q\pi}{2}\) for all \(0< q<1\). Hence \(E_{0}\) is unstable.

Case B. \(k=r\).

-

(iia)

\(rk< cm\). Then \(\Delta_{1}<0\) and (7) has pure imaginary roots \(\lambda_{1}=2\sqrt{cm-rk}i\) and \(\lambda_{3}=-2\sqrt{cm-rk}i\), which mean \(\vert \arg(\lambda_{1,3}) \vert =\frac{\pi}{2}>\frac{q\pi}{2}\) for all \(0< q<1\). Since \(\lambda_{2}<0\), according to Lemma 3, we know that the equilibrium point \(E_{0}\) is locally asymptotically stable.

-

(iib)

\(rk=cm\). From (7), we see that \(\lambda_{1}=\lambda_{2}=0\) and \(\lambda_{3}\) is negative. Then \(E_{0}\) is marginally stable.

-

(iic)

\(rk>cm\). From (7), we know that \(\lambda_{3}=-2\sqrt {rk-cm}\) and \(\lambda_{1}=2\sqrt{rk-cm}\), which imply \(\vert \arg(\lambda _{3}) \vert =\pi>\frac{q\pi}{2}\) and \(\vert \arg(\lambda_{1}) \vert =0<\frac{q\pi}{2}\) for all \(0< q<1\). Hence \(E_{0}\) is unstable.

Case C. \(k< r\).

-

(iiia)

\(rk< cm\). If \(\Delta_{1}\geq0\), then the two eigenvalues \(\lambda_{1}\) and \(\lambda_{3}\) are positive which imply \(\vert \arg(\lambda_{1,3}) \vert =0<\frac{q\pi}{2}\) for all \(0< q<1\). Thus the equilibrium point \(E_{0}\) is unstable. If \(\Delta_{1}<0\), then \(\lambda_{1}\) and \(\lambda_{3}\) are complex conjugates with positive real parts. According to Lemma 3, we know that the equilibrium point \(E_{0}\) is locally asymptotically stable if \(\vert \arg (\lambda_{1,3}) \vert =\arctan(\frac{\sqrt{-\Delta_{1}}}{r-k})>\frac{q\pi}{2}\) is satisfied.

-

(iiib)

\(rk=cm\). It is clear that (7) has a positive eigenvalue \(\lambda_{1}=r-k\), which means \(\vert \arg(\lambda_{1}) \vert =0<\frac{q\pi }{2}\) for all \(0< q<1\). Hence \(E_{0}\) is unstable.

-

(iiic)

\(rk>cm\). Then \(\Delta_{1}=(k+r)^{2}-4cm>0\). From (7), we see that one of the eigenvalues \(\lambda_{1}\) and \(\lambda_{3}\) is positive and the other eigenvalue is negative. Thus the equilibrium point \(E_{0}\) is unstable. This completes the proof of Theorem 1.

□

Remark 1

\(k< r\), \(rk< cm\), \((k+r)^{2}<4cm\), one has \(\vert \arg(\lambda _{1,3}) \vert =\arctan(\frac{\sqrt{-\Delta_{1}}}{r-k})<\frac{\pi}{2}\), where \(\Delta_{1}=(k-r)^{2}-4(cm-rk)\), thus \(q<\frac{2}{\pi}\arctan(\frac{\sqrt {4(cm-rk)-(k-r)^{2}}}{r-k})<\frac{2}{\pi}\times\frac{\pi}{2}=1\).

Remark 2

We notice from Theorem 1 that prey refuge has no influence on the asymptotical stability of trivial equilibrium point \(E_{0}\). In addition, we can see from the proof of Theorem 1 that even if the eigenvalues of the characteristic equation have positive real parts, the trivial equilibrium point \(E_{0}\) of fractional-order system (3) is still locally asymptotically stable when condition \((\mathrm {H}_{2})\) is satisfied. However, for the corresponding integer-order system, namely \(q=1\), if the eigenvalues of the characteristic equation have positive real parts, then the trivial equilibrium point \(E_{0}\) is unstable.

Theorem 2

The predator-extinction equilibrium point \(E_{1}\) of system (3) is locally asymptotically stable if either of the following criteria is satisfied:

- \((\mathrm{H}_{3})\) :

-

\(k^{2}+rk-2cm\geq0\), \(R>\frac{r}{a}-\frac {cm}{ak}-\frac{d}{e}\) and \(rk>cm\).

- \((\mathrm{H}_{4})\) :

-

\(k^{2}+rk-2cm<0\), \(R>\frac{r}{a}-\frac {cm}{ak}-\frac{d}{e}\), \(rk>cm\), \((k^{2}+rk-2cm)^{2}<4k^{2}(rk-cm)\) and \(0< q<\frac{2}{\pi}\arctan(\frac{\sqrt {4k^{2}(rk-cm)-(k^{2}+rk-2cm)^{2}}}{2cm-k^{2}-rk})\).

Proof

At \(E_{1}\), the Jacobian matrix of system (3) is

and the characteristic equation for \(J(E_{1})\) is

The eigenvalues of (9) are

where

Obviously, \(\lambda_{2}\) is negative if \(R>\frac{r}{a}-\frac{cm}{ak}-\frac {d}{e}\). Now we discuss the eigenvalues \(\lambda_{1}\) and \(\lambda_{3}\), it is clear that the cases \(k^{2}+rk-2cm>0\), \(k^{2}+rk-2cm=0\) and \(k^{2}+rk-2cm<0\) are possible, respectively, so we consider three separate cases.

Case D. \(k^{2}+rk-2cm>0\).

-

(iv)

\(rk>cm\). If \(\Delta_{2}\geq0\), we can derive from (10) that the three eigenvalues \(\lambda_{1}\), \(\lambda_{2}\), \(\lambda_{3}\) are negative if \(R>\frac {r}{a}-\frac{cm}{ak}-\frac{d}{e}\), which imply that the equilibrium point \(E_{1}\) is locally asymptotically stable for all \(0< q<1\). In fact, \(\vert \arg(\lambda_{1,2,3}) \vert =\pi>\frac{q\pi}{2}\) for all \(0< q<1\), which satisfy the condition of Lemma 3. If \(\Delta_{2}<0\), then \(\lambda_{1}\) and \(\lambda_{3}\) are complex conjugates with negative real parts, which imply \(\vert \arg(\lambda _{1,3}) \vert =\arctan(\frac{k\sqrt{-\Delta_{2}}}{2cm-k^{2}-rk})+\pi>\frac{q\pi }{2}\) for all \(0< q<1\). According to Lemma 3, we know that the equilibrium point \(E_{1}\) is locally asymptotically stable.

Case E. \(k^{2}+rk-2cm=0\).

-

(v)

\(rk>cm\). Then \(\Delta_{2}<0\), and (9) has pure imaginary roots \(\lambda_{1}=2\sqrt{rk-cm}i\) and \(\lambda_{3}=-2\sqrt{rk-cm}i\), which mean \(\vert \arg(\lambda_{1,3}) \vert =\frac{\pi}{2}>\frac{q\pi}{2}\) for all \(0< q<1\). If \(R>\frac{r}{a}-\frac{cm}{ak}-\frac{d}{e}\) holds, then we have \(\lambda_{2}<0\). According to Lemma 3, we know that the equilibrium point \(E_{1}\) is locally asymptotically stable.

Case F. \(k^{2}+rk-2cm<0\).

-

(vi)

\(rk>cm\). If \(\Delta_{2}\geq0\), then the two eigenvalues \(\lambda_{1}\) and \(\lambda_{3}\) are positive which imply \(\vert \arg(\lambda_{1,3}) \vert =0<\frac{q\pi}{2}\) for all \(0< q<1\). Thus the equilibrium point \(E_{1}\) is unstable. If \(\Delta_{2}<0\), then \(\lambda_{1}\) and \(\lambda_{3}\) are complex conjugates with positive real parts. In addition, if \(R>\frac {r}{a}-\frac{cm}{ak}-\frac{d}{e}\) holds, then we have \(\lambda_{2}<0\). According to Lemma 3, we know that the equilibrium point \(E_{1}\) is locally asymptotically stable if \(\vert \arg(\lambda_{1,3}) \vert =\arctan(\frac {k\sqrt{-\Delta_{2}}}{2cm-k^{2}-kr})>\frac{q\pi}{2}\) is satisfied. This completes the proof of Theorem 2.

□

Remark 3

When \(k^{2}+rk-2cm<0\), \(rk>cm\), \((k^{2}+rk-2cm)^{2}<4k^{2}(rk-cm)\), one has \(\vert \arg(\lambda_{1,3}) \vert =\arctan (\frac{\sqrt{4k^{2}(rk-cm)-(k^{2}+rk-2cm)^{2}}}{2cm-k^{2}-rk})<\frac{\pi}{2}\), thus \(q<\frac{2}{\pi}\arctan(\frac{\sqrt {4k^{2}(rk-cm)-(k^{2}+rk-2cm)^{2}}}{2cm-k^{2}-rk})< \frac{2}{\pi}\times\frac {\pi}{2}=1\).

Finally, we discuss the local stability of the positive equilibrium point of system (3). The Jacobian matrix of system (3) evaluated at the equilibrium \(E_{2}\) is given by

Therefore, the characteristic equation of \(J(E_{2})\) is given by

where

\(D(P)\) denotes the discriminant of the cubic polynomial \(P(\lambda)\), as follows:

Using the results of [27, 28], we have the following proposition.

Proposition 1

The positive equilibrium point \(E_{2}\) is asymptotically stable if either of the following criteria is satisfied:

- \((\mathrm{H}_{5})\) :

-

If \(D(P)>0\), \(F_{1}>0\), \(F_{3}>0\), \(F_{1}F_{2}-F_{3}>0\).

- \((\mathrm{H}_{6})\) :

-

If \(D(P)<0\), \(F_{1}\geq0\), \(F_{2}\geq0\), \(F_{3}>0\), \(0< q<\frac{2}{3}\).

- \((\mathrm{H}_{7})\) :

-

If \(D(P)<0\), \(F_{1}>0\), \(F_{2}>0\), \(F_{1}F_{2}=F_{3}\) for all \(q\in(0,1)\).

Remark 4

We know from Theorems 1 and 2, Proposition 1 that the stability region of system (3) with fractional order \(q\in(0,1)\) is always larger than that of the corresponding integer-order system (\(q=1\)). In addition, with the increment of the fractional order q in the interval \((0,1)\), the corresponding stability region becomes smaller.

4 Numerical simulations

The PECE (Predict, Evaluate, Correct, Evaluate) scheme [29, 30], as a generalization of Adams–Bashforth–Moulton algorithm, is an efficient method to solve fractional-order differential equations. In this section, we apply the PECE scheme for the numerical solution of system (3), which not only confirms our theoretical results but also shows some new findings.

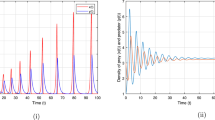

We consider system (3) with parameter values given in case 1 in Table 1 and the initial values are \((10+10k, 1+k,100+200k)\) (\(k=1,2,3\)). For this set of parameter values, the system (3) only exists the trivial equilibrium point \(E_{0}(0,0,0)\). Obviously, condition \((\mathrm{H}_{1})\) holds, we derive from Theorem 1 that the trivial equilibrium point \(E_{0}\) of system (3) is locally asymptotically stable; see Fig. 2(a) and (b). We can see from Fig. 2(a) and (b) that the trivial equilibrium point \(E_{0}\) is not only locally asymptotically stable but also globally asymptotically stable.

We consider system (3) with parameter values given in case 2 in Table 1 and the initial values are \((4+4k, 4+8k,20+20k)\) (\(k=1,2,3\)). For this set of parameter values, the system (3) has two equilibrium points: \(E_{0}(0,0,0)\) and \(E_{1}(10,0,45)\). We can easily verify that the equilibrium point \(E_{0}\) is unstable and only condition \((\mathrm{H}_{3})\) holds, it follows from Theorem 2 that the predator-extinction equilibrium point \(E_{1}\) of system (3) is locally asymptotically stable; see Fig. 3(a) and (b). We can see from Fig. 3(a) and (b) that the predator-extinction equilibrium point \(E_{1}\) is not only locally asymptotically stable but also globally asymptotically stable.

We consider system (3) with parameter values given in case 3 in Table 1 and the initial values are \((10+10k, 1+2k,5+2k)\) (\(k=1,2,3\)). For this set of parameter values, the system (3) has three equilibrium points: \(E_{0}(0,0,0)\), \(E_{1}(90,0,45)\) and \(E_{2}(14,2.66,7)\). By simple calculation, we know that the equilibrium points \(E_{0}\) and \(E_{1}\) are both unstable, only condition \((\mathrm{H}_{5})\) holds, that is,

we obtain from Proposition 1 that the positive equilibrium point \(E_{2}\) of system (3) is locally asymptotically stable; see Fig. 4(a) and (b). We can see from Fig. 4(a) and (b) that the positive equilibrium point \(E_{2}\) is not only locally asymptotically stable but also globally asymptotically stable.

Remark 5

We can see from Figs. 2–4 that feedback control plays an important role in determining the stability of the equilibrium points, feedback control can make extinct populations (prey species and predator species) become coexistent. In addition, by choosing the suitable values of feedback control variables, we can make both prey species and predator species finally reach a better state level, which is suitable for them to survive and develop.

Next, we will depict the impact of fractional order q on the stability of system (3). For the parameters of case 3 in Table 1, we vary parameter q and fix the other parameters. Figure 5(a)–(d) show the solution curves and the phase portrait of system (3) with \(q=0.4\), \(q=0.7\) and \(q=1.0\).

Impact of fractional order q on system (3) with \((x_{0},y_{0},u_{0})=(10,1,5)\)

Remark 6

We can find from Fig. 5(a)–(d) that the convergence of system (3) with \(q=1.0\) is faster than \(q=0.7\), and the convergence of system (3) with \(q=0.7\) is faster than \(q=0.4\), which indicate that the convergence of system (3) becomes fast with the increment of parameter q (\(0< q\leq1\)).

Finally, we will display the impact of prey refuge on each population and feedback control when the positive equilibrium point of system (3) exists. For the parameters of case 3 of Table 1, we vary parameter R, and fix the other parameters. We find from Fig. 6(a) and (c) that \(x^{*}(R)\) and \(u^{*}(R)\) are strictly increasing functions of R, respectively. We also find from Fig. 6(b) that \(y^{*}(R)\) is strictly increasing for \(R\in[0,41]\) and strictly decreasing for \(R\in[41,86]\). Thus, \(y^{*}(R)\) can reach its maximum value at \(R=41\), and the maximum value is 5.0625.

Impact of prey refuge R on system (3) with \((x_{0},y_{0},u_{0})=(30,5,9)\)

Remark 7

Fig. 6(a) shows that prey refuge has positive effect on the prey population. Figure 6(b) shows that the prey refuge initially has a positive effect and later has a negative effect on the predator population. Maybe the reason is that, with the increment of prey refuge, prey individuals are prevented from predation and lead to the increment of prey species, meanwhile the predator density also increases due to the rich food resources. However, when the prey refuge parameter R is greater than a critical value, then an increasing amount of prey refuge can only decrease the predator density and this has happened due to a lack of sufficient food resources.

5 Conclusions

In this paper, we consider a FOPP model incorporating a constant prey refuge and feedback control. We analyze the existence of different equilibrium points, and some criteria are derived to ensure the asymptotical stability of these equilibrium points. Finally, numerical simulations are carried out to illustrate the theoretical results and show that prey refuge and feedback control play important roles in adjusting coexistence of prey species and predator species.

References

Maynard-Smith, J.: Models in Ecology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1974)

Huang, Y., Chen, F., Li, Z.: Stability analysis of a prey–predator model with Holling type III response function incorporating a prey refuge. Appl. Math. Comput. 182, 672–683 (2006)

Chen, F., Chen, L., Xie, X.: On a Leslie–Gower predator–prey model incorporating a prey refuge. Nonlinear Anal., Real World Appl. 10, 2905–2908 (2009)

Ma, Z., Li, W., Zhao, Y., Wang, W., Zhang, H., Li, Z.: Effects of prey refuges on a predator–prey model with a class of functional responses: the role of refuges. Math. Biosci. 218, 73–79 (2009)

Ma, Z.: The research of predator–prey models incorporating prey refuges. Ph.D. Thesis, Lanzhou University, P.R. China (2010)

Chen, F., Ma, Z., Zhang, H.: Global asymptotical stability of the positive equilibrium of the Lotka–Volterra prey–predator model incorporating a constant number of prey refuges. Nonlinear Anal., Real World Appl. 13, 2790–2793 (2012)

Kilbas, A., Srivastava, H., Trujillo, J.: Theory and Application of Fractional Differential Equations. Elsevier, New York (2006)

Podlubny, I.: Fractional Differential Equations. Academic Press, San Diego (1999)

Moustafa, M., Mohd, M., Ismail, A., Abdullah, F.: Dynamical analysis of a fractional-order Rosenzweig–MacArthur model incorporating a prey refuge. Chaos Solitons Fractals 100, 1–13 (2018)

Ahmed, E., El-Sayed, A., El-Saka, H.: Equilibrium points, stability and numerical solutions of fractional-order predator–prey and rabies models. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 325, 542–553 (2007)

Li, H., Zhang, L., Hu, C., Jiang, Y., Teng, Z.: Dynamic analysis of a fractional-order single-species model with diffusion. Nonlinear Anal., Model. Control 22, 303–316 (2017)

Matouk, A., Elsadany, A., Ahmed, E., Agiza, H.: Dynamical behavior of fractional-order Hastings–Powell food chain model and its discretization. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 27, 153–167 (2015)

Huang, C., Cao, J., Xiao, M., Alsaedi, A., Alsaadi, F.: Controlling bifurcation in a delayed fractional predator–prey system with incommensurate orders. Appl. Math. Comput. 293, 293–310 (2017)

Li, H., Zhang, L., Hu, C., Jiang, Y., Teng, Z.: Dynamical analysis of a fractional-order predator–prey model incorporating a prey refuge. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 54, 435–449 (2017)

Heaviside, O.: Electromagnetic Theory. Chelsea, New York (1971)

El-Mesiry, A., Ahmed, E.: On a factional model for earthquakes. Appl. Math. Comput. 178, 207–211 (2006)

Li, H., Jiang, Y., Wang, Z., Hu, C.: Global stability problem for feedback control systems of impulsive fractional differential equations on networks. Neurocomputing 161, 155–161 (2015)

Velmurugan, G., Rakkiyappan, R., Cao, J.: Finite-time synchronization of fractional-order memristor-based neural networks with time delays. Neural Netw. 73, 36–46 (2016)

Gopalsamy, K., Wen, P.: Feedback regulation of logistic growth. Int. J. Math. Sci. 16, 177–192 (1993)

Aizerman, M., Gantmacher, F.: Absolute Stability of Regulator Systems. Holden-Day, San Francisco (1964)

Lefschetz, S.: Stability of Nonlinear Control Systems. Academic Press, New York (1965)

Xu, J., Teng, Z.: Permanence for a nonautonomous discrete single-species system with delays and feedback control. Appl. Math. Lett. 23, 949–954 (2010)

Muroya, Y.: Global stability of a delayed nonlinear Lotka–Volterra system with feedback controls and patch structure. Appl. Math. Comput. 239, 60–73 (2014)

Li, H., Zhang, L., Teng, Z., Jiang, Y., Muhammadhaji, A.: Global stability of an SI epidemic model with feedback controls in a patchy environment. Appl. Math. Comput. 321, 372–384 (2018)

Chen, J., Zeng, Z., Jiang, P.: Global Mittag-Leffler stability and synchronization of memristor-based fractional-order neural networks. Neural Netw. 51, 1–8 (2014)

Petras, I.: Fractional-Order Nonlinear Systems: Modeling, Analysis and Simulation. Higher Education Press, Beijing (2011)

Matouk, A.: Chaos, feedback control and synchronization of a fractional-order modified autonomous Van der Pol-Duffing circuit. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 16, 975–986 (2011)

Mondal, S., Lahiri, A., Bairagi, N.: Analysis of a fractional order eco-epidemiological model with prey infection and type 2 functional response. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 40, 6776–6789 (2017)

Diethelm, K., Ford, N., Freed, A.: A predictor–corrector approach for the numerical solution of fractional differential equations. Nonlinear Dyn. 29, 3–22 (2002)

Diethelm, K., Ford, N., Freed, A.: Detailed error analysis for a fractional Adams method. Numer. Algorithms 36, 31–52 (2004)

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the editors and anonymous referees for their valuable suggestions and comments, which greatly improved the presentation of this paper.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This work is supported by Natural Science Foundation of Xinjiang (Grant No. 2017D01C082).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, HL., Muhammadhaji, A., Zhang, L. et al. Stability analysis of a fractional-order predator–prey model incorporating a constant prey refuge and feedback control. Adv Differ Equ 2018, 325 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-018-1776-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-018-1776-7