Abstract

Polypores have been applied in traditional Chinese medicine up to the present day, and are becoming more and more popular worldwide. They show a wide range of bioactivities including anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, antiviral and immuno-enhancing effects. Their secondary metabolites have been the focus of many studies, but the importance of fungal strain for bioactivity and metabolite production has not been investigated so far for these Basidiomycetes. Therefore, we screened several strains from three medicinal polypore species from traditional European medicine: Fomes fomentarius, Fomitopsis pinicola and Piptoporus betulinus. A total of 22 strains were compared concerning their growth rates, optimum growth temperatures, as well as antimicrobial and antifungal properties of ethanolic fruit body extracts. The morphological identification of strains was confirmed based on rDNA ITS phylogenetic analyses. Our results showed that species delimitation is critical due to the presence of several distinct lineages, e.g. within the Fomes fomentarius species complex. Fungal strains within one lineage showed distinct differences in optimum growth temperatures, in secondary metabolite production, and accordingly, in their bioactivities. In general, F. pinicola and P. betulinus extracts exerted distinct antibiotic activities against Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus at minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) ranging from 31-125 μg mL−1; The antifungal activities of all three polypores against Aspergillus flavus, A. fumigatus, Absidia orchidis and Candida krusei were often strain-specific, ranging from 125-1000 μg mL−1. Our results highlight that a reliable species identification, followed by an extensive screening for a ‘best strain’ is an essential prerequisite for the proper identification of bioactive material.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polypores are a diverse group of Agaricomycetes (Basidiomycota) with tough poroid hymenophores. These fungi have been extensively applied in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) up to the present day (Chang 2000; Chang and Wasser 2012; Hobbs 1995; Ying et al. 1987) and are becoming more and more popular also in other parts of the world where they are used as a source for medicinal compounds and therapeutic adjuvants, or as health food supplements. They show a wide range of bioactivities including anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, antiviral and immuno-enhancing effects (Grienke et al. 2014; Molitoris 2005; Paterson 2006). The large number of scientific studies focusing on their bioactivity (Khatun et al. 2011; Lo and Wasser 2011; Xu et al. 2010; Zhao 2013; Zhong and Xiao 2009; Zhou et al. 2011), secondary metabolite production (Hwang et al. 2013; You et al. 2013) and genomics (Floudas et al. 2012; Liu et al. 2012) is therefore not surprising.

Secondary metabolites of medicinal polypores have been the focus of many studies (Grienke et al. 2014; Zjawiony 2004), but the importance of fungal strain for bioactivity and metabolite production has not been investigated so far. Strain-specific differences in bioactivities (on the function of macrophages) were detected for different strains of the Ascomycete Ophiocordyceps sinensis, whose fruit bodies are highly praised as traditional remedy (Meng et al. 2013). Distinct strain differences are also known for anamorphic ascomycetes, e.g. for the secondary metabolite production of Fusarium avenaceum, where substrate is playing an additional important role in the regulation of secondary metabolite biosynthesis (Sørensen and Giese 2013).

Fungal medicinal polypore species belonging to the same genus differ clearly in their metabolite profile (Hseu et al. 1996; Lv et al. 2012).

Species delimitation of polypores was long based upon macro-morphological and ecological characters. However, these classical morphological species concepts have proven to be too wide for many important medicinal polypore species, e.g. for Ganoderma lucidum, G. applanatum, or Laetiporus sulphureus (Banik et al. 2010; Banik et al. 2012; Hseu et al. 1996, Ota et al. 2009). Polypore species, described upon morphology as generalists on several hosts, have often turned out to consist of multiple phylogenetic (cryptic) lineages, and the description of new species if often necessary within such species complexes (Skaven Seierstad et al. 2013). This makes comparison of studies working on metabolites from medicinal polypores forming a morphological species complex especially critical and difficult. It is therefore essential to document, from which habitat and substrate the fruit body was obtained, to deposit a voucher in a public mycological collection and a culture in a public culture collection, in order to check or to re-identify the fungus. Moreover, it is also recommended to sequence barcoding regions of the investigated fungal material, in order to allow for a later verification of the identification of the fungus.

A recent study on the secondary metabolites of the medicinal polypore Laricifomes officinalis was carried out in an exemplary way by also including rDNA ITS sequences of the used strain (Hwang et al. 2013). But screening for optimal strains is rarely carried out, and strain differences within polypore species are usually not taken into account, although it is well known that a large variety of existing alleles are promoting outcrossing of polypores; genetic exchange in dikaryons by somatic recombination creates additional new combinations of alleles (Peabody et al. 2000). This implies that ecologically relevant genetic variation permanently occurs within dikaryotic fungal individuals, allowing for evolutionary adaptation and thus for the evolution of physiologically distinct strains.

To study polypore species with known bioactivities allows for an easy and straightforward comparison of different strains from one species, e.g. for their antimicrobial properties or their metabolic fingerprint. We therefore investigated strain-specific differences of three medicinal polypore species of the traditional European medicine. The applications of these polpores in traditional medicine, and knowledge on their metabolite profile have been extensively reviewed by Grienke et al. (2014).

When using defined commercially available culture strains, interpretation of the results is often difficult due to lack of information, e.g. on the environment, substrate, or on the fruit body morphology. We therefore used newly isolated strains, and extensively documented their habitat, substrate, and the morphology of fruit bodies. This also allowed for a comparison of strains based on both, bioactivities of fruit body extracts and the physiological properties of cultures in vitro.

Physiological properties are often used for species delimitation because they reflect genetic distance: Fomes strains belonging to different species have different physiological properties, like colony growth responses to temperature (McCormick et al. 2013). The question whether also strains within one species, e.g. F. fomentarius, differ in growth responses to temperature was not addressed so far.

The main aim of this work was to study the influence of fungal strain (isolate) of three selected, medicinal polypores on their antimicrobial bioactivity and physiological properties. The bioactivity was assessed for ethanolic extracts from the same fruit bodies, which had been used for isolation of mycelial cultures. Bioactivity was tested against potentially pathogenic fungi and bacteria. Physiological properties of mycelial cultures (colony growth rate and optimum temperature) were investigated under standard in vitro conditions. All polypore strains used were characterized by rDNA ITS sequences, and phylogenetic analyses were carried out to verify species identification. The potential influence of geographic provenance and substrate on strain evolution and properties are discussed.

Material and methods

Organism collection, identification, culture

F. fomentarius, F. pinicola, and P. betulinus fruit bodies were mainly collected in Tyrol, Austria in 2013. Fruit body vouchers were deposited in the Mycological Collection of the Herbarium Innsbruck (IB), cultures were deposited in the Jena Microbial Resource Collection (JMRC), sequences were deposited in GenBank. Voucher numbers, GenBank accession numbers, JMRC collection numbers, plant hosts, as well as habitat information are given in Table 1.

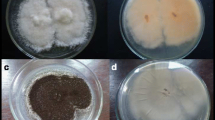

Sterile techniques were used to obtain cultures from the context tissue. Small pieces of context tissue (2.0 mm3) were excised from each basidiome, plated on 2-3 % w/v malt extract agar plates (MEA Art. Nr. X976.2 from Roth Karlsruhe Germany) and incubated for one to three weeks at a temperature of 20°C. Cultures were checked regularly for contaminations. Mycelial plugs of 1-3 mm in diameter were taken from the edge of the mycelium and transferred to new plates, to establish pure cultures and further carrying out growth experiments.

The tissue cultures and stock cultures are maintained at the Institute of Microbiology, University of Innsbruck, Austria. For cryopreservation small parts of well-growing cultures were overlaid with 10 % glycerol (Sigma), incubated for 1 h at room temperature, plugged out and stored at −80°C. Isolates were also stored on malt extract agar (MEA) slants at 4°C. The partial sequences of ITS rRNA genes allowed for the identification of the strains. Sequence data are available from GenBank (Table 1). Phylogenetic analyses were used to confirm the morphological identification of all strains and to test for sequence divergence.

Colony growth temperature experiments

Five isolates of F. fomentarius, and 11 isolates of F. pinicola and 3 isolates of P. betulinus were grown on plates containing 25 mL MEA. After 14 d, four mycelia plugs (5 mm diam.) were taken 1 cm from the leading edge of the colony and transferred to the middle of plates of 9 cm diam. containing 25 mL MEA. Plates were randomly placed into a plastic box, and incubated at six different temperatures (10, 20, 25, 30, 32 and 37°C). Mean colony diameter (mm), minus the 5 mm plug, was measured after 2, 5, 7 and 10 days. The results are expressed as means ± standard deviations of three parallel cultures. Significant differences between colony growth response to temperature on different days were identified using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (p < 0.05) followed by post-hoc Tukey’s HSD test (α = 0.05), using R version 3.1.0 (2014-04-10) for Windows (R Development Core Team, 2014).

DNA amplification and sequence analysis

Molecular identification of isolated mycelia was performed using sequence data of the ITS regions of the ribosomal DNA. Total genomic DNA was isolated from 100 μg of fungal matter (one-month-old mycelial cultures or fresh basidiome) by DNeasy® Plant Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions and then eluted in 50 μl of sterile water. ITS-1, 5.8S rRNA and ITS-2 regions were amplified in a 50 μl volume reaction containing 1-10 ng of genomic DNA, using the primers pair ITS1 and ITS4 in a T gradient Thermal Cycler (primus 96; Peqlab, Germany) according to Peintner et al. (2001). PCR products were sequenced by Microsynth AG (Switzerland) with the primer ITS4. Sequences were analysed using the Sequencher® software (version 5.2.3; Gene Codes, Ann Arbor, MI, USA).

As a first step, Blast searches were conducted in GenBank (http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), and closely related sequences were downloaded. Only a small part of identical sequences were downloaded in order to cover geographical range and substrate preferences. Alignment and phylogenetic analyses were carried out with MEGA 5.2 (Tamura et al. 2011).

Sequences were aligned and manually adjusted in MEGA 5.2 for each genus. To evaluate branch robustness of trees, parsimony-based bootstrap analyses were applied. ML analyses were conducted based on the best ML model estimated. Bootstrap analyses were conducted using 1000 replications, SPR search method, search-level 5. The alignment and phylograms have been submitted to TreeBASE (http://treebase.org).

Ethanolic extraction of fruit bodies

For each strain 1 g of dried and milled fruit body was placed in a glass centrifugation tube and immersed in 30 mL 96% EtOH. The tube was covered with aluminium foil and sonicated for 20 min at room temperature. After centrifuging for 5 min at 3 500 rpm the supernatant was filtered through a Pasteur pipette stuffed with cotton wool. After washing of the fungal material with 10 mL of 96% EtOH, the combined extract was evaporated to dryness. The dry ethanolic extracts were dissolved in 96% EtOH to a final concentration of 10 mg mL−1. These stock solutions were stored at −20°C.

HPLC analysis of fungal extracts

HPLC analyses were carried out using a Shimadzu UFLC XR device at 40°C, a flow rate of 1.0 mL min−1, injection volume was 10 μL, detection wavelength 254 nm. The stationary phase was a Phenomenex® HyperClone ODS (C18) column, 120 Å, 5 μm, 150 × 4.60 mm; mobile phase A: H2O + 0.9% AA + 0.1% FA; mobile phase B: CH3CN + 0.9% AA + 0.1% FA; 0 min: 90% A to 30 min: 2% A, 30-35 min: 2% A.

Bioactivity of fungal extracts

Screenings for antibiotic/antifungal activities of EtOH extracts were carried out in 96-well micro plates. Four bacterial strains (Escherichia coli ATCC 11229, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853, Bacillus subtilis MB37) and four potential pathogenic or toxin-producing fungal species (Absidia orchidis, Aspergillus fumigatus, A. flavus and Candida krusei) were used for quantitative bioassays. All microorganisms were tested separately: Micro plates were inoculated with one test organism, each, and used to either test five fungal extracts at 8 concentrations, or 10 fungal extracts at 4 concentrations. Negative, positive and solvent controls were included on each micro plate.

In vitro antibacterial assays

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined using the broth microdilution method (serial 2fold dilutions) as recommended by the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI 2012). The lowest concentration leading to no growth (i.e. no turbidity), as assessed by macroscopic evaluation was taken as the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC).

Bacterial cultures were maintained on LB agar slants. Each bacterial strain was streaked out on a LB agar plate and incubated for 24 hours at 35 ± 2°C. Four to five single standing colonies were used to inoculate 20-50 mL LB in 100 mL Erlenmeyer flasks. The bacteria were allowed to grow for 6-8 hours at 35 ± 2°C and 150 rpm until a slight turbidity was obtained. The cell density was checked with a cytometer (Thomakammer). Bacteria were diluted in sterile LB to a density of 106 cells mL−1 and vortexed thoroughly. Bacterial suspension was added to the micro plates as described below. Sterility controls for broth and flasks were included, and bacterial inoculum was always streaked out on an LB plate to check for contamination.

Sterile 96-well micro plates (columns 1-12, rows A-H) were filled with 50 μL LB. Starting from column 3 (to 10) serial two-fold dilutions of either fungal extracts or control antibiotic (tetracycline, H3-10) were made, with the highest concentration starting at 1000 μg mL−1 (final). One row received the same volume of solvent (96% EtOH) as introduced with the fungal extracts, while another row received deion. sterile water, to determine any possible inhibiting effect of the solvent on bacterial growth. Afterwards, 50 μL of bacterial suspension were added to each well, except those in the last two columns (11, 12) to a give final cell concentration of 5 × 105 mL−1. Columns 11 and 12 instead received another 50 μL of sterile LB (final volume 100 μL) and worked as broth sterility controls. Columns 1 and 2 received sterile LB and bacterial inoculum and worked as growth controls.

The micro plates were sealed with parafilm® to prevent desiccation and edge effects and incubated for 20 h at 35 ± 2°C. Plates were evaluated by visually checking for growth by comparing the turbidity in the wells with that of the growth and broth control, respectively. Only plates with completely turbid growth, as well as clear broth controls were analysed.

For determination of bactericidal effects 10 μL of each test well showing growth inhibition in the primary screening were transferred into 100 μL fresh LB and incubated for 48 h. The specific concentrations were accepted as bactericidal, if no growth occurred after incubation in a concentration lower than the corresponding MIC.

No technical replicates were integrated in the primary screening in order to save as much of the restricted amount of extracts available. Therefore the lowest test concentration showing an inhibitory effect was repeated in 3 parallels. If this second test showed the same results, the results were considered as verified. If not, the test was repeated with the next highest concentration of the dilution series until the MIC could be verified. Fungal extracts themselves usually increased the turbidity of the medium (debris, pigments), therefore an extra micro plate containing only fungal extracts in LB was set up as a reference to aid visual comparison.

In vitro antifungal assays

For filamentous fungi, a 96-well based micro plate approach was carried out similar to the one described by Troskie et al. (2012). Absidia orchidis, A. flavus and A. fumigatus were cultivated on potato dextrose agar (PDA) until sporulation set in (approx. one week). Spores were harvested in 3 mL Tween20 (0.1% in aqua dest.) and spore density was assessed using a cytometer (Neubauer). The spore solution was diluted in 0.5 × strength potato dextrose broth (PDB) to a density of 105 spores mL-1. Candida krusei was streaked out on a PDA plate, and incubated for 24 h at 35 ± 2°C. Four to five single standing colonies were used to inoculate 20-50 mL PDB in 100 mL Erlenmeyer flasks. The yeasts were allowed to grow for 6-8 h at 35 ± 2°C and 150 rpm until a slight turbidity was obtained. The cell density was checked with a cytometer (Neubauer). Yeasts were diluted in sterile PDB to a cell density of 105 mL−1 and 20 μL well−1 of this yeast inoculum were used to inoculate the micro plates.

Micro plates were filled with 70 μL sterile 1 × strength PDA. Plates were sealed in plastic bags and stored at 4°C until the assay was started. Test substance stock solutions and 0.5 x strength PDB were combined in the wells to final concentrations of 1000, 500, 250 and 125 μg mL−1, respectively. Cycloheximide (serial dilutions starting at 1000 μg mL−1) as well as the serial dilutions of 96% EtOH were integrated on changing positions, and used as negative control (AB susceptibility control) and as solvent inhibition control, respectively. Thereafter, 20 μL of spore solution were added to each well, except to the broth sterility control wells. Micro plates were incubated at 25°C for at least 48 h. Then the wells were checked for fungal growth using a stereo microscope. A subsequent protein staining of the plates with Coomassie Blue G250 was carried out as described by (Troskie et al. 2012) to allow discrimination between fungal biomass and precipitates of fruit body extracts.

Candida krusei micro plates were prepared based on the layout and protocol for filamentous fungi. However only liquid PDB was used, and micro plates were shaken periodically (for 5” every 30’) to avoid on-surface growth.

Results

Hosts, isolation, and cultivation of fungal strains

In sum, nineteen fungal strains were isolated for this study: five strains of F. fomentarius, 11 strains of F. pinicola, and three strains of P. betulinus. Strains were isolated from a narrow geographical area spanning a maximum of hundred kilometres, with a few control strains isolated form the southern side of the Alps, and one strain from the mediterranean area. F. fomentarius was isolated from Fagus sylvatica, Picea abies and Quercus pubescens; F. pinicola was isolated from Abies alba, Alnus incana, Larix decidua and P. abies. P. betulinus was isolated from Betula pubescens only.

HPLC analysis of fruit body extracts

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) of fruit body extracts showed that polypore strains differ in both, qualitative and quantitative secondary metabolite production. F. fomentarius strain IB20130019 was significantly different by showing an extremely poor production of secondary metabolites. F. pinicola strains showed a very high variation in the quantity of secondary metabolites produced (Additional file 1: Figure S1).

Bioactivity of extracts

Bioactivity of F. fomentarius extracts

Fruit body extracts from all strains of F. fomentarius showed minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of 250-500 μg mL−1 against Staphylococcus aureus, and MICs of 125-500 μg mL−1 against A. fumigatus (Ascomycota) and A. orchidis (Zygomycota) (Table 2). The only exception was strain IB20130019, which was isolated from a subalpine habitat and a Fagus sylvatica substrate. This strain was not bacteriostatic at concentrations ≤ 500 μg mL−1, nor fungistatic at ≤ 1000 μg mL−1 against A. orchidis. HPLC chromatograms confirmed that both, the quantity and quality of secondary metabolites produced by this strain IB20130019 are clearly different from secondary metabolites produced by the other strains.

The Mediterranean isolate IB20130033, which belongs to another clade, was the only strain showing an effect against Candida krusei at 1000 μg mL−1. This strain produced significantly higher quantities of secondary metabolites than the other strains (Additional file 1: Figure S1).

Bioactivity of F. pinicola extracts

F. pinicola extracts showed good bacteriostatic and bactericidal bioactivities with MICs of 31-125 μg mL−1 against B. subtilis and of 31-500 μg mL−1 against S. aureus. A general antifungal activity was detected against A. fumigatus, and most F. pinicola strains had also antifungal activity against Absidia orchidis at 500-1000 μg mL−1. Three strains (IB20130026, IB20130030, IB20130037) showed an additional antifungal activity against A. flavus. All these latter strains are from other substrates (Abies, Alnus, Picea, and Larix) than Picea abies.

Bioactivity of P. betulinus extracts

P. betulinus extracts showed a good antibacterial activity against B. subtilis (MIC 62.5 μg mL−1, MBC 500 μg mL−1) and S. aureus (MIC/MBC 31 μg mL−1). Extracts inhibited the growth of Absidia orchidis at 500-1000 μg mL−1, and caused abnormal growth of A. fumigatus.

Growth rates of fungal strains

Colony growth and optimum temperatures of F. fomentarius strains

The three F. fomentarius strains isolated from Picea (IB20130011, IB20130016, and IB20130022) showed similar colony diameters after 7 d of incubation at different temperatures, with optimal growth temperatures of 25 or 30°C, leading to a mean colony diameter of 7.0-8.1 cm (Figure 1A and Additional file 1: Table S1). The growth kinetics at 25°C (i.e. increase in colony diameter per measurement) were also similar for these strains. In comparison, the strain isolated from F. sylvatica (IB20130019) was growing slower on all tested temperatures, with a maximum of 5 cm colony diameter reached after 7 d incubation at 25°C (optimum temperature) and significantly lower growth kinetics (Figure 1B) This can be due to the previous growth on Fagus as a host, or due to the provenance from a subalpine area at 1300 m a. s. l. The strain isolated form Q. pubescens (IB20130033) also differed significantly from all other strains, with a relatively slow growth at 25°C and 30°C compared to the Picea-derived strains, and the highest measured colony diameter compared to all Fomes strains (8.7 ± 0.5 cm) at 32°C. (Figure 1). This strain differs by its provenance from a sub-Mediterranean area, and by growing on Quercus as a host from all other strains.

Mean colony diameter of isolated F. fomentarius strains on MEA (n = 3 per strain). A. After 7 days of incubation at different temperatures. B. Mean growth kinetics at 25°C. ANOVA result at 25°C (optimal growth temperature for major part of strains) p = 1.345e-05. Strains with significant differences after post hoc test: 20130019-20130011 (p = 0.006); 20130019-20130016 (p = 0.001); 20130019-20130022 (p = 0.0003); 2013-0033-20130011 (p = 0.0003); 20130033-20130016 (p = 0.00009); 20130033-20130022 (p = 0.00003).

Colony growth and optimum temperatures of F. pinicola strains

Most F. pinicola strains isolated from Picea had an optimal growth temperature of 25°C after 7d. Only two Picea-derived strains (IB20130018 and IB20130021) differed by having an optimum temperature of 30°C (Figure 2A). However, for these two strains the differences in colony diameter between 25 and 30°C were not significant (Additional file 1: Table S2). Picea strains, although originating from the same substrate, exhibited different growth kinetics (Figure 2B and Additional file 1: Table S2). Strains from Alnus (IB20130026) and Larix (IB20130030) substrates had a strikingly different temperature optimum of 32°C and different growth kinetics (Figures 2A and 2B).

Mean colony diameter of isolated F. pinicola strains on MEA (n = 3 per strain). A. After 7 days of incubation at different temperatures. B. Mean growth kinetics at 25°C. ANOVA result at 25°C (optimal growth temperature) p = 0.000125. Strains with significant differences after post hoc test: 20130026-20130010 (p = 0.028); 20130026-20130015 (p = 0.002); 20130026-20130040 (p = 0.006); 20130026-20130042 (p = 0.04); 20130030-20130010 (p = 0.004); 20130030-20130013 (p = 0.018); 20130030-20130015 (p = 0.0002); 20130030-20130018 (p = 0.04); 20130030-20130021 (p = 0.03); 20130030-20130040 (p = 0.0008); 20130030-20130042 (p = 0.006).

Colony growth and optimum temperatures of P. betulinus strains

The optimum growth temperature for the three isolated P. betulinus strains was at 25°C (Figure 3A and Additional file 1: Table S3), with no significant differences between strains regarding optimum temperature or growth kinetics (Figure 3B), not even for strain IB20130055, although it was isolated from another geographical region.

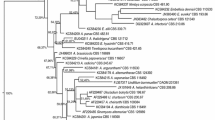

Phylogenetic placement of polypore strains based on rDNA ITS sequences

Phylogenetic placement of F. fomentarius strains

The phylogenetic analysis of F. fomentarius sequences generated for this study showed that the geographic origin and the substrate are important factors driving speciation in this genus of facultative opportunistic phytopathogenic Basidiomycetes. The phylogenetic tree allows for distinction of four well-supported clades within F. fomentarius (BS > 75 %). Fomes fasciatus was used as outgroup (Figure 4).

Phylogenetic placement of F. fomentarius strains inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the Kimura 2-parameter model. The tree with the highest log likelihood (-1266,9966) is shown. Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying Neighbor-Join and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using the Maximum Composite Likelihood (MCL) approach, and then selecting the topology with superior log likelihood value. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. The analysis involved 43 nucleotide sequences. All positions with less than 95% site coverage were eliminated. That is, fewer than 5% alignment gaps, missing data, and ambiguous bases were allowed at any position. There were a total of 505 positions in the final dataset. Bootstrap values above 75 % are given (1 000 replications). Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA6.

Our strains clustered into two clades: the four strains isolated from the alpine range fell within a clade of F. fomentarius sequences with origin in the Northern European countries (Russia, Poland, Latvia, Slovak Republic, Germany, Austria, Slovenia), and F. sylvatica, Alnus spp., Acer negundo and P. abies as substrates. This Northern European clade is sister to a clade of F. fomentarius from the U.S.A and China from Betula spp. substrates.

Our Mediterranean strain (IB20130033) was placed within another, distinct clade of F. fomentarius sequences originating mostly from Southern European countries (Italy, France, Portugal, Slovenia) and other substrates (Platanus x acerifolia, Populus spp., Quercus spp. and Abies). The only exceptions are F. fomentarius sequences from the Slovak Republic. This Southern European clade is sister to a distinct clade of F. fomentarius from China.

Within clade sequence divergence was small, with 0-3 base pair differences between the different strains of F. fomentarius from Northern European countries. Sequence divergence between the Northern and Southern European clade was 9-18 base pairs, and sequence divergence to the outgroup F. fasciatus was 41-62 base pairs.

Phylogenetic placement of F. pinicola strains

F. pinicola is a polypore with very little sequence divergence between strains. Only sequences from USA or Asia showed some sequence divergence in addition to F. ochracea, which forms a distinct clade within F. pinicola, thus making this clade paraphyletic (Figure 5). We found very little sequence divergence between all our strains: Sequence divergence to other isolates of F. pinicola was 1-5 base pairs out of 504 positions, to other species of Fomitopsis (F. meliae, F. palustris) 15-21 base pairs.

Phylogenetic placement of F. pinicola strains inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the Hasegawa-Kishino-Yano model. The tree with the highest log likelihood (-1629.3947) is shown. Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained by applying the Neighbor-Joining method to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using the Maximum Composite Likelihood (MCL) approach. A discrete Gamma distribution was used to model evolutionary rate differences among sites (5 categories (+G, parameter = 0.3750)). The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. The analysis involved 61 nucleotide sequences. All positions with less than 95% site coverage were eliminated. There were a total of 504 positions in the final dataset. Bootstrap values above 75 % are given (1 000 replications). Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA6.

Phylogenetic placement of P. betulinus strains

P. betulinus is a polypore species with little rDNA ITS sequence variation between different strains from a broad geographic area (Europe, Russia, East Asia) and Betula spp. or Acer saccharum as substrate (Figure 6): Within species sequence divergence was very low: P. betulinus sequences differed only in 1-2 out of > 500 base pairs from each other, but had 44-45 differed base pairs when compared to the sister taxon P. soloniensis.

Phylogenetic placement of P. betulinus strains inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the Kimura 2-parameter model. The tree with the highest log likelihood (−529.8218) is shown. Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained by applying the Neighbor-Joining method to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using the Maximum Composite Likelihood (MCL) approach. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. The analysis involved 18 nucleotide sequences. All positions with less than 95% site coverage were eliminated. That is, fewer than 5% alignment gaps, missing data, and ambiguous bases were allowed at any position. There were a total of 256 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA6.

Discussion

Fungal strain matters

Our results confirmed our hypothesis that medicinal polypore strains belonging to the same lineage differ significantly in their qualitative and quantitative secondary metabolite production, and in bioactivity. This confirms earlier studies focusing on other medicinal polypore species showing that the fungal strain used is important for the chemical composition of fruit bodies (Agafonova et al. 2007) and also for the production of bioactive secondary metabolites (Lv et al. 2012; Sørensen and Giese 2013). We therefore recommend that strain selection and preliminary bioactivity testing should become common practice for all studies focusing on constituents and biological effects of medicinal polypores. Fungal strain selection is routinely applied for a wide range of species used for food (Chiu et al. 1999; Liu et al. 2012; Terashima et al. 2002), biotechnology (Geiger et al. 2012), and biocontrol (Cui et al. 2014).

All strains used in this study were isolated from those fruit bodies which were later used for extraction and bioactivity testing. Their colony growth rates were tested under standard conditions in order to investigate strain-specific properties without the influence of different substrates or environmental factors. When considering only strains of F. fomentarius belonging to the same lineage, the quantity and quality of secondary metabolites produced by temperate strains showed clear differences. One strain isolated from Fagus (IB20130019) exhibited significantly different growth characteristics compared to all other strains isolated from Picea: It was growing significantly slower and had a lower optimal temperature. This strain was also extremely differing in metabolite production and bioactivity.

Also F. pinicola strains isolated from Picea had different growth rates and optimum temperatures than strains isolated from other substrates (Abies, Alnus, or Larix) even when originating from the same geographical area. Bioactivity tests confirmed these strain-specific differences, because all strains from other substrates had a stronger antifungal activity than strains isolated from Picea. This suggests that substrate is a strong trigger for or may influence metabolite production. In any case, the strain-specific differences remained stable under standardized conditions (in vitro). Additional studies comparing extracts from wild-grown fruit bodies with extracts from fruit bodies cultivated in vitro (under standard conditions) from the same strain will further elucidate the influence of strain characteristics on the metabolite profile and the respective bioactivities. Testing different environmental parameter and substrates is a suitable method to pre-select strains of medicinal polypores and their growth conditions for upscaling to increase the biosynthesis of bioactive secondary metabolites.

The influence of substrate on bioactivity and metabolites from fruit bodies

Metabolite production is often substrate dependent, and selected bioactive metabolites may be produced on selected substrates only (Shang et al. 2012), or produced in significantly different quantities (Sørensen and Giese 2013). Even minor variations in environment or nutrition have the potential to affect the quantity and diversity of fungal metabolites. The deliberate elaboration of cultivation parameters to influence the secondary metabolism of a strain has been called the OSMAC (one strain, many compounds) approach (Bode et al. 2002). Substrate modifications have already been used to enhance secondary metabolite production and bioactivity of the most popular medicinal polypores, i.e. Reishi (G. lucidum) (You et al. 2012) and Chaga (Inonotus obliquus) (Xu and Zhu 2011). In F. fomentarius, submerged culturing processes were optimized for the production of bioactive polysaccharides (Chen et al. 2008, Chen et al. 2011) and for laccase production (Neifar et al. 2011). Up to now, we are not aware of studies focusing on the effect of substrate on the bioactivity of medicinal polypore fruit bodies. Future studies based on fruit bodies cultivated under controlled conditions and on different substrates will help to elucidate this issue.

The medicinal potential of F. fomentarius, F. pinicola and P. betulinus

Our bioactivity screening generally confirms the potential of F. fomentarius, F. pinicola and P. betulinus as medicinal polypores. Because of their bioactivity against gram-positive bacteria, and their potency as antifungal agent, we especially consider F. pinicola to be worth further investigation on a molecular level. This fungus was widely applied in traditional European medicine, but its benefits and utilisation have been forgotten after the introduction of synthetic drugs. Due to renaissance of naturopathy and also due to increasing bacterial and fungal resistances, working with traditional medicinal fungi is becoming increasingly interesting and rewarding.

Most of our polypore extracts inhibited the growth of the gram-positive bacterium S. aureus and of the potentially pathogenic fungus Absidia orchidis (Mucorales); In addition, we detected varying bioactivities (MICs of 31-1000 μg mL−1) for B. subtilis, Aspergillus flavus, A. fumigatus and Candida krusei. These varying bioactivities are either species-specific, or related to strain properties.

Crude extracts are generally a mixture of active and non-active compounds, and MICs < 100 μg mL−1 generally suggest good antimicrobial activity (Dellavalle et al. 2011; Webster et al. 2008). In this research, MIC values were often lower than 100 μg mL−1, demonstrating strong antibacterial activity of extracts under study. Antifungal activities were slightly higher with lowest values of 125 μg mL−1. The MIC of our F. pinicola extracts against B. subtilis (31-125 μg mL−1) can be considered as very good, especially when compared to MIC values as previously reported for six isolated F. pinicola compounds against B. cereus (16-128 μg mL−1) (Liu et al. 2010). The MICs of our P. betulinus extracts (31-62.5 μg mL−1) are also significant, but slightly higher than the values of 17.5 μg mL−1 achieved based on agar-well diffusion assays, as reported for Serbian P. betulinus extracts against antibiotic-resistant gram-positive bacteria (Bacillus sp., Rhodococcus equi, and S. aureus). We could not detect significant bioactivity against gram-negative bacteria (Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Escherichia coli), as earlier reported for a P. betulinus strain from Serbia (Karaman et al. 2009).

It is difficult to compare results on bioactivity of different studies, because of the different extraction methods, test organisms and test systems applied. Frequently used test systems are the agar cup method (Popova et al. 2009), the agar dilution assay (Guler et al. 2009), a TLC bioassay (Keller et al. 1996), or standard MIC assays based on the broth micro-dilution method (CLSI, 2012) as used in this study. Also in vivo models have been applied (Seniuk et al. 2011; Seniuk et al. 2013). Moreover, research groups use different samples in their test models, e.g. whole fungal extracts (Karaman et al. 2009; Turkoglu et al. 2007), fractions (Lemieszek et al. 2009) or single compounds (Hwang et al. 2013). Finally, species identification and documentation is often fragmentary, thus not allowing for direct comparison of results.

Species delimitation first, then strain selection

The present study highlights the importance of exact species delimitation in medicinal polypores as a prerequisite for correct species identification. For F. pinicola and P. betulinus, the morphological species concepts widely agree with the phylogenetic species delimitation. F. pinicola phylograms showed little genetic differentiation, because this is a highly outcrossing heterothallic fungus, with panmictic conditions (Högberg et al. 1999). Also P. betulinus has very low sequence divergence between strains from geographically distant origins, e.g. Canada, Asia and Europe.

Fomes fomentarius can rather be considered to be a species complex (Judova et al. 2012; Pristas et al. 2013), as corroborated by our phylogenetic analysis: North European, South European, and Asian F. fomentarius strains fall into three distinct lineages, and representatives of each lineage are growing on different host tree species. Therefore, these lineages should be considered as distinct Fomes species representing different lineages of evolution. Our F. fomentarius strain isolated from Quercus from a sub-Mediterranean area (IB20130033) belongs to the well-supported South European clade, and has comparatively large sequence divergence to all our strains from the temperate area. Thus, we consider this Mediterranean F. fomentarius strain as a distinct taxon. This strain also differs from temperate strains by a significantly higher temperature optimum, and different growth rates, thus supporting a hypothesis suggesting that tropical species of wood-decay fungi are characterized by a higher temperature optima for growth (30-40°C) than temperate wood decay fungi (20-30°C) (Magan 2008). Growth rates have been shown to be species-specific in Fomes (McCormick et al. 2013), which is further supporting our hypothesis that this lineage represents a distinct species.

Species delimitation is an important issue in medicinal fungi, because the production of bioactive secondary metabolites is first species-specific, and then depending on strain characteristics. Physiological properties, e.g. growth rates and optimum temperature, are generally useful characters for species delimitation in fungi (Jaklitsch 2009) and have been applied for corticoid (Hallenberg and Larsson 1991) and poroid (McCormick et al. 2013) wood-inhabiting Basidiomycota. Also pigments and other metabolites are good indicators for the distinction of fungal taxa (Breheret et al. 1997; Frisvad et al. 2008). The European name Ganoderma lucidum (= Reishi mushroom), for example, has been widely applied on a global scale, but represents several distinct lineages or species (Wang et al. 2012), which differ in their secondary metabolite profiles (Lv et al. 2012). Also Laetiporus sulphureus, which is another important medicinal polypore, includes several lineages representing distinct species with different geographic origin and from different hosts (Banik et al. 2012). Ecological adaptation through host shifts and substratum specialization is likely to be an important mode of speciation and adaptive radiation in polypores (Skaven Seierstad et al. 2013). A successful screening on bioactive secondary metabolites must therefore be based on two stable pillars: first, a reliable species identification followed by an extensive screening for a suitable or ‘best strain’.

References

Agafonova SV, Olennikov DN, Borovskii GB, Penzina TA (2007) Chemical composition of fruiting bodies from two strains of Laetiporus sulphureus. Chem Nat Compd 43(6):687–688, doi:10.1007/s10600-007-0229-4

Banik MT, Lindner DL, Ota Y, Hattori T (2010) Relationships among North American and Japanese Laetiporus isolates inferred from molecular phylogenetics and single-spore incompatibility reactions. Mycologia 102(4):911–917, doi:10.3852/09-044

Banik MT, Lindner DL, Ortiz-Santana B, Lodge DJ (2012) A new species of Laetiporus from the Caribbean basin. Kurtziana 37:15–21

Bode HB, Bethe B, Hofs R, Zeeck A (2002) Big effects from small changes: possible ways to explore nature's chemical diversity. Chembiochem 3(7):619–627, doi:10.1002/1439-7633(20020703)3:7<619::aid-cbic619>3.0.co;2-9

Breheret S, Talou T, Rapior S, Bessiere JM (1997) Volatile compounds: A useful tool for the chemotaxonomy of Basidiomycetes. Cryptogam Mycol 18:111–114

Chang STMK (2000) Ganoderma lucidum-Paramount among medicinal mushrooms. Discov Innovat 12:97–101

Chang ST, Wasser SP (2012) The role of culinary-medicinal mushrooms on human welfare with a pyramid model for human health. Int J Med Mushrooms 14:95–134, doi:10.1615/IntJMedMushr.v14.i2.10

Chen W, Zhao Z, Chen S-F, Li Y-Q (2008) Optimization for the production of exopolysaccharide from Fomes fomentarius in submerged culture and its antitumor effect in vitro. Bioresource Technol 99:3187–3194, doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2007.05.049

Chen W, Zhao Z, Li Y (2011) Simultaneous increase of mycelial biomass and intracellular polysaccharide from Fomes fomentarius and its biological function of gastric cancer intervention. Carbohyd Polym 85:369–375, doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2011.02.035

Chiu SW, Wang ZM, Chiu WT, Lin FC, Moore D (1999) An integrated study of individualism in Lentinula edodes in nature and its implication for cultivation strategy. Mycol Res 103:651–660, doi:10.1017/S095375629900859X

CLSI (2012) CLSI methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically vol M07-A9. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA

Cui Q, Zhang Y, Zang Y, Nong X, Wang G, Zhang Z (2014) Screening of high toxic Metarhizium strain against Plutella xylostella and its marking with green fluorescent protein World. J Microbiol Biotechn:1–7 doi:10.1007/s11274-014-1700-6

Dellavalle PD, Cabrera A, Alem D, Larranaga P, Ferreira F, Dalla Rizza M (2011) Antifungal activity of medicinal plant extracts against phytopathogenic fungus Alternaria spp. Chil J Agr Res 71:231–239, doi:10.4067/S0718-58392011000200008

Floudas D, Binder M, Riley R, Barry K, Blanchette RA, Henrissat B, Martinez AT, Otillar R, Spatafora JW, Yadav JS, Aerts A, Benoit I, Boyd A, Carlson A, Copeland A, Coutinho PM, de Vries RP, Ferreira P, Findley K, Foster B, Gaskell J, Glotzer D, Gorecki P, Heitman J, Hesse C, Hori C, Igarashi K, Jurgens JA, Kallen N, Kersten P et al (2012) The paleozoic origin of enzymatic lignin decomposition reconstructed from 31 fungal genomes. Science 336:1715–1719, doi:10.1126/science.1221748

Frisvad JC, Andersen B, Thrane U (2008) The use of secondary metabolite profiling in chemotaxonomy of filamentous fungi. Mycol Res 112:231–240, doi:10.1016/j.mycres.2007.08.018

Geiger M, Gibbons J, West T, Hughes SR, Gibbons W (2012) Evaluation of UV-C mutagenized Scheffersomyces stipitis strains for ethanol production. J Lab Automat 17:417–424, doi:10.1177/2211068212452873

Grienke U, Zöll M, Peintner U, Rollinger JM (2014) European medicinal polypores – A modern view on traditional uses. J Ethnopharmacol 154(3):564–583, doi:10.1016/j.jep.2014.04.030

Guler P, Akata I, Kutluer F (2009) Antifungal activities of Fomitopsis pinicola (Sw.:Fr) Karst and Lactarius vellereus (Pers.) Fr. Afr J Biotechnol 8:3811–3813, doi:10.5897/AJB09.719

Hallenberg N, Larsson E (1991) Differences in cultural characters and electrophoretic patterns among sibling species in four different species complexes (Corticiaceae, Basidiomycetes). Mycologia 83(2):131–141

Hobbs C (1995) Medicinal mushrooms: An exploration of tradition, healing and culture. Botanica Press, Santa Cruz

Högberg N, Holdenrieder O, Stenlid J (1999) Population structure of the wood decay fungus Fomitopsis pinicola. Heredity 83:354–360, doi:10.1046/j.1365-2540.1999.00597.x

Hseu RS, Wang HH, Wang HF, Moncalvo JM (1996) Differentiation and grouping of isolates of the Ganoderma lucidum complex by random amplified polymorphic DNA-PCR compared with grouping on the basis of internal transcribed spacer sequences. Appl Environ Microbiol 62:1354–1363

Hwang CH, Jaki BU, Klein LL, Lankin DC, McAlpine JB, Napolitano JG, Fryling NA, Franzblau SG, Cho SH, Stamets PE, Wang Y, Pauli GF (2013) Chlorinated coumarins from the polypore mushroom Fomitopsis officinalis and their activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Nat Prod 76:1916–1922, doi:10.1021/np400497f

Jaklitsch WM (2009) European species of Hypocrea Part I. The green-spored species. Stud Mycol 63:1–91, doi:10.3114/sim.2009.63.01

Judova J, Dubikova K, Gaperova S, Gaper J, Pristas P (2012) The occurrence and rapid discrimination of Fomes fomentarius genotypes by ITS-RFLP analysis. Fungal Biol 116:155–160, doi:10.1016/j.funbio.2011.10.010

Karaman M, Mimica-Dukic N, Knezevic P, Svircev Z, Matavuly M (2009) Antibacterial properties of selected lignicolous mushrooms and fungi from Northern Serbia. Int J Med Mushrooms 11:269–279, doi:10.1615/IntJMedMushr.v11.i3.60

Keller AC, Maillard MP, Hostettmann K (1996) Antimicrobial steroids from the fungus Fomitopsis pinicola. Phytochemistry 41:1041–1046, doi:10.1016/0031-9422(95)00762-8

Khatun S, Islam A, Cakilcioglu U, Chatterjee NC (2011) Research on mushroom as a potential source of nutraceuticals: A review on Indian perspective. Am J Exp Agric 2(1):47–73, doi:10.9734/AJEA/2012/492

Lemieszek MK, Langner E, Kaczor J, Kandefer-Szerszen M, Sanecka B, Mazurkiewicz W, Rzeski W (2009) Anticancer effect of fraction isolated from medicinal birch polypore mushroom, Piptoporus betulinus (Bull.: Fr.) P. Karst. (Aphyllophoromycetideae): in vitro studies. Int J Med Mushrooms 11:351–364, doi:10.1615/IntJMedMushr.v11.i4.20

Liu X-T, Winkler AL, Schwan WR, Volk TJ, Rott M, Monte A (2010) Antibacterial compounds from mushrooms II: lanostane triterpenoids and an ergostane steroid with activity against Bacillus cereus isolated from Fomitopsis pinicola. Planta Med 76:464–466, doi:10.1055/s-0029-1186227

Liu D, Gong J, Dai W, Kang X, Huang Z, Zhang H-M, Liu W, Liu L, Ma J, Xia Z, Chen Y, Chen Y, Wang D, Ni P, Guo A-Y Xiong X (2012) The genome of Ganderma lucidum provides insights into triterpene biosynthesis and wood degradation. PLoS ONE 7:e36146, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036146

Lo H-C, Wasser SP (2011) Medicinal mushrooms for glycemic control in diabetes mellitus: History, current status, future perspectives, and unsolved problems (review). Int J Med Mushrooms 13:401–426, doi:10.1615/IntJMedMushr.v13.i5.10

Lv GP, Zhao J, Duan JA, Tang YP, Li SP (2012) Comparison of sterols and fatty acids in two species of Ganoderma. Chem Cent J 6:10, doi:10.1186/1752-153x-6-10

Magan N (2008) Chapter 4 Ecophysiology: Impact of environment on growth, synthesis of compatible solutes and enzyme production. In: Boddy L, Frankland JC, van West P (eds) British Mycological Society Symposia Series, vol 28. Academic Press, pp 63–78. doi:10.1016/S0275-0287(08)80006-9

McCormick MA, Grand LF, Post JB, Cubeta MA (2013) Phylogenetic and phenotypic characterization of Fomes fasciatus and Fomes fomentarius in the United States. Mycologia 105:1524–1534, doi:10.3852/12-336

Meng L-Z, Lin B-Q, Wang B, Feng K, Hu D-J, Wang L-Y, Cheong K-L, Zhao J Li S-P (2013) Mycelia extracts of fungal strains isolated from Cordyceps sinensis differently enhance the function of RAW 264.7 macrophages J Ethnopharm 148:818–825. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2013.05.017

Molitoris HP (2005) Fungi: companions of man in good and evil. Int J Med Mushrooms 7:49–73, doi:10.1615/IntJMedMushr.v7.i12.70

Neifar M, Kamoun A, Jaouani A, Ellouze-Ghorbel R, Ellouze-Chaabouni S (2011) Application of asymetrical and hoke designs for optimization of laccase production by the white-rot fungus Fomes fomentarius in solid-state fermentation. Enzyme Res 2011:368525–368525, doi:10.4061/2011/368525

Ota Y, Hattori T, Banik MT, Hagedorn G, Sotome K, Tokuda S, Abe Y (2009) The genus Laetiporus (Basidiomycota, Polyporales) in East Asia. Mycol Res 113:1283–1300, doi:10.1016/j.mycres.2009.08.014

Paterson RRM (2006) Ganoderma - A therapeutic fungal biofactory. Phytochemistry 67:1985–2001, doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.07.004

Peabody RB, Peabody DC, Sicard KM (2000) A genetic mosaic in the fruiting stage of Armillaria gallica. Fungal Genet Biol 29:72–80, doi:10.1006/fgbi.2000.1187

Peintner U, Bougher NL, Castellano MA, Moncalvo JM, Moser MM, Trappe JM, Vilgalys R (2001) Multiple origins of sequestrate fungi related to Cortinarius (Cortinariaceae). Biological Abstracts 101(Iss 5, Ref 64553 88):2168–2179

Popova M, Trusheva B, Gyosheva M, Tsvetkova I, Bankova V (2009) Antibacterial triterpenes from the threatened wood-decay fungus Fomitopsis rosea. Fitoterapia 80:263–266, doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2009.02.008

Pristas P, Gaperova S, Gaper J, Judova J (2013) Genetic variability in Fomes fomentarius reconfirmed by translation elongation factor 1-α DNA sequences and 25S LSU rRNA sequences. Biologia 68:816–820, doi:10.2478/s11756-013-0228-9

Seniuk OF, Gorovoj LF, Beketova GV, Savichuk HO, Rytik PG, Kucherov II, Prilutskay AB, Prilutsky AI (2011) Anti-infective properties of the melanin-glucan complex obtained from medicinal tinder bracket mushroom, Fomes fomentarius (L.: Fr.) Fr. (Aphyllophoromycetideae). Int J Med Mushrooms 13:7–18, doi:10.1615/IntJMedMushr.v13.i1.20

Seniuk OF, Gorovoi LF, Kovalev VA, Palamar LA, Krul NI, Zhidkov AV, Chemerskii GF, Kireev SI, Khatuntseva IV (2013) Features of behavioral reactions of chronically irradiated mice in the raised crosswise labyrinth with various genetically determined radiosensitivity and possibilities of their modification by the fungal biopolymer complex. Radiatsionnaia biologiia, radioecologiia / Rossiiskaia akademiia nauk 53:170–182

Shang Z, Li X-M, Li C-S, Wang B-G (2012) Diverse secondary metabolites produced by marine-derived fungus Nigrospora sp. MA75 on various culture media. Chem Biodiversity 9:1338–1348, doi:10.1002/cbdv.201100216

Skaven Seierstad K, Carlsen T, Sætre G-P, Miettinen O, Hellik Hofton T, Kauserud H (2013) A phylogeographic survey of a circumboreal polypore indicates introgression among ecologically differentiated cryptic lineages. Fungal Ecology 6:119–128, doi:10.1016/j.funeco.2012.09.001

Sørensen JL, Giese H (2013) Influence of carbohydrates on secondary metabolism in Fusarium avenaceum. Toxins 5:1655–1663, doi:10.3390/toxins5091655

Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S (2011) MEGA5: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis using Maximum Likelihood, Evolutionary Distance, and Maximum Parsimony Methods. Mol Biol Evol 28(10):2731–2739, doi:10.1093/molbev/msr121

Terashima K, Matsumoto T, Hasebe K, Fukumasa-Nakai Y (2002) Genetic diversity and strain-typing in cultivated strains of Lentinula edodes (the shii-take mushroom) in Japan by AFLP analysis. Mycol Res 106:34–39, doi: 10.1017/S0953756201005007

Troskie AM, Vlok NM, Rautenbach M (2012) A novel 96-well gel-based assay for determining antifungal activity against filamentous fungi. J Microbiol Methods 91:551–558, doi:10.1016/j.mimet.2012.09.025

Turkoglu A, Duru ME, Mercan N, Kivrak I, Gezer K (2007) Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Laetiporus sulphureus (Bull.) Murrill. Food Chemistry 101:267–273, doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.01.025

Wang X-C, Xi R-J, Li Y, Wang D-M, Yao Y-J (2012) The species identity of the widely cultivated Ganoderma, ‘G. lucidum’ (Ling-zhi), in China. PLoS ONE 7:e40857, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040857

Webster D, Taschereau P, Belland RJ, Sand C, Rennie RP (2008) Antifungal activity of medicinal plant extracts; preliminary screening studies. J Ethnopharmacology 115:140–146, doi:10.1016/j.jep.2007.09.014

Xu X, Zhu J (2011) Enhanced phenolic antioxidants production in submerged cultures of Inonotus obliquus in a ground corn stover medium. Biochem Eng J 58–59:103–109, doi:10.1016/j.bej.2011.09.003

Xu K, Liang X, Gao F, Zhong JJ, Liu JW (2010) Antimetastatic effect of ganoderic acid T in vitro through inhibition of cancer cell invasion. Process Biochem 45:1261–1267, doi:10.1016/j.procbio.2010.04.013

Ying J. MX, Ma Q., Zong Y. and Wen H. (1987) Icons of medical fungi from China Science Press, Bejing

You BL, Lee HZ, Chung KR, Lee MH, Huang MJ, Tien N, Chan CW, Kuo YH (2012) Enhanced production of ganoderic acids and cytotoxicity of Ganoderma lucidum using solid-medium culture. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 76:1529–1534, doi:10.1271/bbb.120270

You B-J, Lee M-H, Tien N, Lee M-S, Hsieh H-C, Tseng L-H, Chung Y-L Lee H-Z (2013) A novel approach to enhancing ganoderic acid production by Ganoderma lucidum using apoptosis induction. PLoS ONE 8:e53616, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0053616

Zhao Y-Y (2013) Traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, pharmacokinetics and quality control of Polyporus umbellatus (Pers.) Fries: A review. J Ethnopharmacology 149:35–48, doi:10.1016/j.jep.2013.06.031

Zhong JJ, Xiao JH (2009) Secondary metabolites from higher fungi: discovery, bioactivity, and bioproduction. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol 113:79–150, doi: 10.1007/10_2008_26

Zhou L, Shi P, Chen NH, Zhong JJ (2011) Ganoderic acid Me induces apoptosis through mitochondria dysfunctions in human colon carcinoma cells. Process Biochem 46:219–225, doi:10.1016/j.procbio.2010.08.014

Zjawiony JK (2004) Biologically Active Compounds from Aphyllophorales (Polypore Fungi). J Nat Prod 67:300–310, doi:10.1021/np030372w

Acknowledgements

We thank Georg Walch for helping with the isolation and cultivation of fungal strains, Wolfgang Burgstaller for his useful comments on the manuscript, and Regina Kuhnert for maintaining and curating of the mycological collection IB. This project was financed by the research budget of the Institute of Microbiology, University of Innsbruck.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

UP, UG and JMR participated in the design of the experiment. MNA and KR isolated the polypore strains, identified them, and performed the physiological testing of the strains, UG extracted polypore fruit bodies and performed the HPLC analyses, PD performed all bioactivity testing experiments and analyzed the data, UP made the phylogenetic analyses, PD and UP wrote the manuscript. UG, MNA, and JMR edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

HPLC chromatograms of fruit body extracts and colony growth of fungal strains under different temperatures.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dresch, P., D´Aguanno, M.N., Rosam, K. et al. Fungal strain matters: colony growth and bioactivity of the European medicinal polypores Fomes fomentarius, Fomitopsis pinicola and Piptoporus betulinus . AMB Expr 5, 4 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-014-0093-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-014-0093-0