Abstract

Background

Mosquitoes are vectors of many pathogens, such as malaria, dengue virus, yellow fever virus, filaria and Japanese encephalitis virus. Wolbachia are capable of inducing a wide range of reproductive abnormalities in their hosts, such as cytoplasmic incompatibility. Wolbachia has been proposed as a tool to modify mosquitoes that are resistant to pathogen infection as an alternative vector control strategy. This study aimed to determine natural Wolbachia infections in different mosquito species across Hainan Province, China.

Methods

Adult mosquitoes were collected using light traps, human landing catches and aspirators in five areas in Hainan Province from May 2020 to November 2021. Species were identified based on morphological characteristics, species-specific PCR and DNA barcoding of cox1 assays. Molecular classification of species and phylogenetic analyses of Wolbachia infections were conducted based on the sequences from PCR products of cox1, wsp, 16S rRNA and FtsZ gene segments.

Results

A total of 413 female adult mosquitoes representing 15 species were identified molecularly and analyzed. Four mosquito species (Aedes albopictus, Culex quinquefasciatus, Armigeres subalbatus and Culex gelidus) were positive for Wolbachia infection. The overall Wolbachia infection rate for all mosquitoes tested in this study was 36.1% but varied among species. Wolbachia types A, B and mixed infections of A × B were detected in Ae. albopictus mosquitoes. A total of five wsp haplotypes, six FtsZ haplotypes and six 16S rRNA haplotypes were detected from Wolbachia infections. Phylogenetic tree analysis of wsp sequences classified them into three groups (type A, B and C) of Wolbachia strains compared to two groups each for FtsZ and 16S rRNA sequences. A novel type C Wolbachia strain was detected in Cx. gelidus by both single locus wsp gene and the combination of three genes.

Conclusion

Our study revealed the prevalence and distribution of Wolbachia in mosquitoes from Hainan Province, China. Knowledge of the prevalence and diversity of Wolbachia strains in local mosquito populations will provide part of the baseline information required for current and future Wolbachia-based vector control approaches to be conducted in Hainan Province.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Wolbachia belongs to the family Ehrlichiaceae in the order Rickettsiales. It is a group of endosymbiotic bacteria which is maternally inherited and found in many species of arthropods and nematodes [1, 2]. It is estimated that Wolbachia naturally infects as many as 25–70% of insect species [3,4,5], including a large range of mosquito vector species that are responsible for transmitting diseases in humans such as malaria, dengue, yellow fever, filariasis and Japanese encephalitis [1, 6, 7]. Wolbachia can induce reproductive manipulation phenotypes, including parthenogenesis, feminization, cytoplasmic incompatibility and male-killing, which increase the endosymbiont’s reproductive success [8,9,10].

Traditional insecticide-based vector control measures are widely used for transmission reduction and disease prevention [11]. Due to widespread mosquito resistance to chemical insecticides [12, 13], new viable alternatives are vital for vector and pathogen transmission control. Wolbachia-based biological control is one of those novel alternatives [14]. It is an ecologically friendly and potentially cost-effective method for the prevention and control of many arboviral infections such as dengue and Zika viruses [15]. In Aedes mosquitoes, Wolbachia can induce cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI), i.e. when Wolbachia-infected male mosquitoes mate with uninfected females, viable offspring are not produced. This serves as the basis for the suppression of field Aedes mosquito population, i.e. mass-rearing and mass release of Wolbachia-infected male mosquitoes to suppress the field Aedes mosquito population while preventing dengue virus transmission, the so-called population suppression strategy [14]. Such a mass release has been conducted in serval countries such as China, Singapore, Australia and the USA [17,18,19,20]. Another strategy is population replacement followed by suppression, aiming to reduce the natural mosquito population size after the Wolbachia infection has been established [14]. Once the Wolbachia infection is at a high frequency, host fitness costs can reduce the size of the population by the reduced mosquito survival or fertility [21]. In addition, when a combination of different strains of Wolbachia is introduced into Aedes mosquito eggs, the dengue virus is unable to replicate in the modified mosquitoes that hatch [22]. These pathogen-blocking effects serve as the principle for direct dengue virus transmission control because the females pass the Wolbachia to their offspring; mass release of pathogen-blocking Wolbachia-infected female Aedes mosquitoes can lead to reduced dengue virus-carrying female Aedes mosquitoes [23, 24]. We have to keep in mind that simple natural infection such as mono-wAlbA or -wAlbB or combined wAlbA and wAlbB may not be enough to fully prevent arboviral infections [25]. In fact, not all the population replacement programs were successful [26], and choosing the right Wolbachia strain is key for the success [14]. All these indicate the importance of research on Wolbachia ecology and population genetics.

Although Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes have been tested as biocontrol agents in the field in China [16], the presence of naturally occurring endosymbionts such as Wolbachia in wild (field-collected) mosquito populations has not been adequately assessed [27,28,29]. Understanding Wolbachia infection prevalence, bacteria strains, infected mosquito species and spatial distribution of infections is essential for developing future vector control and disease prevention strategies.

Hainan Province, the largest island province in the South China Sea, has a tropical climate and is an ideal place for the development and survival of mosquitoes. More than 60 species of mosquitoes were reported in Hainan Province in the 1960s [30], and recent studies reported more than 20 species [31, 32]. Many mosquito-borne diseases, such as malaria, dengue and filariasis, have recently been or still are prevalent in Hainan Province; for example, a dengue fever outbreak occurred there in 2019 [33, 34]. Therefore, from a disease prevention point of view, it would be very useful to understand the prevalence and phylogenetic relationship of Wolbachia among different mosquito species.

This study had two research objectives. The first aim was to examine the natural prevalence of Wolbachia infections among wild mosquitoes collected from areas with different ecological settings in Hainan Province using Wolbachia-specific DNA markers, Wolbachia surface protein (wsp) and PCR-based molecular approaches. The second aim was to determine the genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationships of Wolbachia strains among wild-collected mosquitoes based on wsp, 16S rRNA and cell division protein FtsZ (FtsZ) markers.

Methods

Study sites and mosquito sampling

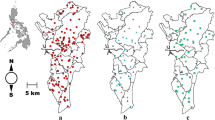

Five study sites with different ecological settings were selected to examine the Wolbachia natural infection status in different mosquito species across Hainan Province between May 2020 and November 2021 (Fig. 1). Three methods were deployed to collect the adult mosquito samples: CDC light trap, human landing catch and hand aspirator. Mosquitoes were morphologically identified using taxonomic keys [35]. A subset of 413 female mosquitoes from different species was preserved in ethyl alcohol at − 20 °C for subsequent molecular species identification, Wolbachia detection and population genetics analyses.

DNA extraction and mosquito species identification

Before DNA extraction, all mosquito samples (n = 413) were surface sterilized with 75% ethanol for 5 min followed by washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) twice. Genomic DNA was extracted from mosquitoes individually using the method published by Chang et al. [36]. The extracted DNA was run on a 1.0% agarose gel electrophoresis to confirm its presence. Then, extracted DNA was stored at − 20 °C or used immediately for PCR.

For mosquito species identification, mosquitoes were first morphologically divided into Anopheles, Culex, Aedes, Armigeres and other species. Molecular identifications of Anopheles sinensis, Culex quinquefasciatus and Aedes albopictus were conducted using species-specific PCR primers (forward: TGTGAACTGCAGGACACATGAA and reverse: AGGGTCAAGGCATACAGAAGGC for An. sinensis [37]; forward: CCTTCTTGAATGGCTGTGGCA and reverse: TGGAGCCTCCTCTTCACGG for Cx. quinquefasciatus [38]; forward: CACCCGTGTATGTGCGATATTA and reverse: TTGGTCGTTCGGTGGTAAAG for Ae. albopictus [39]). For other mosquito species identification, Sanger sequencing was performed to target a fragment of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (cox1) gene using primers LCO1498 (5ʹ-GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG-3ʹ) and HCO2198 (5ʹ-TAAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAAAATCA-3ʹ) [40]. PCR procedures were performed in reaction mixtures consisting of 12.5 μl of DreamTaq™ Green PCR Master Mix (2×) (Thermo Scientific, USA), 1 μl extracted DNA and 1 μl each of 10-μM forward and reverse primers. Double-distilled water was used to top up the reaction mixture to a final volume of 25 μl. PCR amplification of positive and negative controls was also conducted simultaneously. PCR conditions were as follows: 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 53 °C for 45 s and 72 °C for 1 min, with a final elongation step of 72 °C for 10 min.

PCR identification of Wolbachia infections in field-collected mosquitoes

Detection of the Wolbachia endosymbiont in mosquitoes was performed using the most commonly used Wolbachia-specific DNA marker (wsp gene) and PCR-based molecular approaches with forward primer (81F: TGGTCCAATAAGTGATGAAGAAAC) and reverse primer (691R: AAAAATTAAACGCTACTCCA) [41]. To classify Wolbachia groups of infected Ae. albopictus, further PCR amplification of the wsp gene was conducted using wAlbA primers (328F: 5ʹ-CCAGCAGATACTATTGCG-3ʹ and 691R: 5ʹ-AAAAATTAAACG CTACTCCA-3ʹ) for A group and wAlbB primers (183F: 5ʹ-AAGGAACCGAAGTTCATG-3' and 691R: 5'-AAAAATTAAACGCTACTCCA-3') for B group [41]. PCR amplification was performed in a 25-μl reaction volume with 12.5 μl DreamTaq™ Green PCR Master Mix (2×) (Thermo Scientific, USA), 0.5 μl each of the forward and reverse primers at 10 μmol/l, 0.5 μl of template DNA and sufficient nuclease-free water to make 25 μl. PCR conditions were as follows: an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 3 min followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. Five microliters of the PCR products was run on 1.5% agarose gel with a DL2000 DNA marker (Zomanbio, Beijing, China) to confirm the PCR amplification. PCR-amplified fragments of 364 bp and 509 bp for wAlbA and wAlbB, respectively, were revealed under UV light after electrophoresis. Sanger sequencing of PCR products was conducted on a subset of PCR-positive samples to confirm Wolbachia infections.

Genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationship of Wolbachia strains

To determine the genetic diversity and phylogenetics of naturally infected Wolbachia strains in different mosquito species, we conducted DNA sequencing of the three conserved Wolbachia genes: 16S rRNA gene [42,43,44], Wolbachia surface protein (wsp) gene [41] and Wolbachia cell division protein (FtsZ) gene [45]. Primers used are shown in Additional file 1: Table S1. DNA extracted from Haikou adult Aedes albopictus (infected with the wAlbA and wAlbB strains of Wolbachia) was used as a positive control [46] in addition to no-template controls (NTCs). PCR amplifications were performed in reaction mixtures consisting of 12.5 μl of DreamTaq™ Green PCR Master Mix (2×) (Thermo Scientific, USA), 0.5 μl of extracted DNA and 1 μl each of 10-μM wsp forward and reverse primers for Wolbachia PCR screens. Double-distilled water was used to top up the reaction mixture to a final volume of 25 μl. PCR conditions were as follows: 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 45 s for wsp and 16S rRNA gene primers or 60 °C for 45 s for FtsZ cell cycle gene primers, and 72 °C for 1 min, with a final elongation step of 72 °C for 10 min. Nested PCR amplifying the 16S rRNA gene was used to detect Wolbachia in all mosquito samples. The initial PCR employed 16S Wolbachia-specific primers (W-Specf: 5ʹ-CATACCTATTCGAAGGGATAG-3ʹ; W-Specr: 5ʹ-AGCTTCGAG TGAAACCAATTC-3ʹ) and was performed in a 25-µl reaction volume using 2 µl DNA [43]. Then, 2 µl of the initial PCR products was amplified in a 25 µl PCR reaction using specific internal primers (16SNF: 5ʹ-GAAGGGATAGGGTCGGTT CG-3ʹ; 16SNR: 5ʹ-CAATTCCCATGGCGTGACG-3ʹ) [42]. All amplicons were separated by gel electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gel stained with GoodView Nucleic Acid Stain (Sbsbio, Beijing, China) and visualized under an ultraviolet fully automatic digital gel imaging analysis system (Tanon, Shanghai, China). PCR products were submitted to Sangon Biotech (Sangon BiotechCo., Ltd, Shanghai, China) for PCR reaction cleanup, followed by Sanger sequencing to generate both forward and reverse reads, using a 3730XL DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA).

Data analysis

The CodonCode Aligner 9.0.2 (CodonCode Corporation, Centerville, MA, USA) was used to check the sequence quality and trim low-quality bases. Ambiguous sequences were omitted from the results. BioEdit Sequence Alignment Editor software [47] was used to align the sequences. All aligned DNA sequences were compared with other sequences available in the GenBank database to determine the percentage identity using BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), and the most similar sequences were downloaded for phylogenetic analysis. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using MEGA version X software [48]. Phylogenetic relationships were inferred using the UPGMA method. Nucleotide sequences generated in this study have been submitted to GenBank (accession numbers OP279050-OP279063, OP367764-OP367777, OP363894-OP363900, OP393144-OP393149 and OP426265-OP426271).

Results

Mosquito abundance and diversity at study sites

Overall, 413 female individuals belonging to six genera and 15 species were identified from the five collection sites (Table 1). Among them, 173 (41.9%) belonged to Anopheles, 80 (19.4%) to Culex, 112 (27.1%) to Aedes, 43 (10.4%) to Armigeres, 3 (0.7%) to Mansonia and 2 (0.5%) to Toxorhynchites. Among the 15 mosquito species identified, 131 mosquitoes (31.7%) were An. sinensis, 90 (21.8%) Ae. albopictus, 75 (18.2%) Cx. quinquefasciatus, 43 (10.4%) Armigeres subalbatus, 28 (6.8%) Anopheles vagus, 18 (4.4%) Aedes lineatopennis and 28 (6.8%) others (Aedes vexans, Culex tritaeniorhynchus, Cx. gelidus, Cx. pipiens, Anopheles campestris, An. crawfordi, An. kochi, An. tessellatus, Mansonia uniformis and Toxorhynchites splendens) (Table 1). Qiongzhong and Danzhou had the greatest mosquito diversity among the five study sites with eight mosquito species each, and Haikou had the lowest diversity with three species (Additional file 2: Table S2).

All 413 mosquitoes were examined for Wolbachia infection based on the presence/absence of wsp genes. Four species, Ae. albopictus, Cx. quinquefasciatus, Cx. gelidus and Ar. subalbatus, were positive for Wolbachia infection, with an overall infection rate of 36.1% (149/413). Wolbachia infection rates varied substantially among infected species, with the lowest (37.2%) occurring in Ar. subalbatus and the highest (86.7%) in Ae. albopictus (Table 1). In Ae. albopictus, the majority of mosquitoes (64.1%, 50/78) were infected with both wAlbA and wAlbB strains of Wolbachia; mono-strain wAlbA and wAlbB infection rates were 21.1% and 10.0%, respectively (Additional file 3: Table S3). Aedes albopictus in Haikou had the highest infection rate (100%) and Lingao the lowest (65.0%). No Wolbachia infection was detected in any Anopheles mosquitoes.

The prevalence of Wolbachia infection also varied substantially among study sites (Fig. 2). Notably, not all mosquito species were found at all study sites, and sample sizes varied by species and study site (Additional file 3: Table S3); therefore, it is difficult to compare the composition of Wolbachia infections among different sites (Fig. 2).

Genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationship of Wolbachia strains

A subset of 40 Wolbachia-infected female mosquitoes from the four species Ae. albopictus, Ar. subalbatus, Cx. quinquefasciatus and Cx. gelidus was used for DNA sequencing of the host cox1 gene and three Wolbachia-specific genes (wsp, FtsZ and 16S rRNA). A total of 14 cox1 haplotypes were identified from the four mosquito species Ae. albopictus (5), Ar. subalbatus (6), Cx. quinquefasciatus (2) and Cx. gelidus (1). A total of five wsp haplotypes, six FtsZ haplotypes and six 16S rRNA haplotypes were detected from Wolbachia infections (Table 2). At least four Wolbachia strains (alb-wspH1/alb-FtsZH1/alb-16sH1, alb-wspH1/alb-FtsZH1/alb-16sH3, alb-wspH2/alb-FtsZH2/alb-16sH2 and alb-wspH1/alb-FtsZH3/alb-16sH1) were detected in Ae. albopictus, whereas two strains (sub-wspH1/sub-FtsZH1/sub-16sH1 and sub-wspH2/sub-FtsZH2/sub-16sH2) were found in Ar. subalbatus and one in each of Cx. quinquefasciatus (qui-wspH1/qui-FtsZH1/qui-16sH1) and Cx. gelidus (gel-wspH1/gel-FtsZH1/gel-16sH1).

Phylogenetic tree analysis of the mosquito cox1 gene showed clear separation into three clades, corresponding to the three genera (Aedes, Armigeres and Culex) (Fig. 3). Wsp sequences were classified into three groups of Wolbachia strains, corresponding to previously reported types A and B and a new group, namely type C (Fig. 4a). Both FtsZ (Fig. 4b) and 16S rRNA (Fig. 4c) sequences were classified into two clades. When combining the three Wolbachia genes, the sequences of all mosquito specimens (single infection, n = 35) were grouped into three clades, corresponding to types A and B and type C (Fig. 5). The Wolbachia infections of Ae. albopictus were clearly classified into two clades (type A and type B) and which of Cx. gelidus was classified as type C, like those classifications based on wsp gene alone. The majority of Wolbachia infections in Ar. subalbatus were classified into type A, whereas two of them were grouped into type B. All the Wolbachia infections in Cx. quinquefasciatus were grouped into type B infections.

Phylogenetic tree analysis of cox1 haplotypes of different mosquito species collected in Hainan Province. Phylogenetic inference was performed using the UPGMA method. The percentage of replicate trees (> 50) in which the associated haplotypes clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) is shown next to each branch. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Kimura two-parameter method; units are the number of base substitutions per site. Colored dots indicate haplotypes of different species identified in this study; numbers in parentheses indicate the abundance of each haplotype. Species name followed by GenBank accession number is provided for reference

Phylogenetic tree analysis of the haplotypes of three Wolbachia-specific genes detected from mosquitoes in Hainan Province. a wsp gene sequences, b FtsZ gene sequences, c 16 s rRNA gene sequences in Wolbachia strains. Phylogenetic inference was performed using the UPGMA method. The percentage of replicate trees (> 50) in which the associated haplotypes clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) is shown next to each branch. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Kimura two-parameter method; units are the number of base substitutions per site. Colored dots indicate haplotypes of different species identified in this study; numbers in parentheses indicate the abundance of each haplotype. Species name followed by GenBank accession number is provided for reference

Multiple-loci sequence alignment analysis (MLSA) and phylogenetic inference of Wolbachia haplotypes resulting from combining three genes (wsp, FtsZ and 16 s rRNA) detected from mosquitoes in Hainan Province. Phylogenetic inference was performed using the UPGMA method. The percentage of replicate trees (> 50) in which the associated haplotypes clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) is shown next to each branch. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Kimura two-parameter method; units are the number of base substitutions per site. Pink dots indicate individuals infected with wAlbA strain, while blue dots indicated individuals infected wAlbB strain, determined by both wsp gene alone and combining with FtsZ and 16 s rRNA sequencing in Aedes albopictus

Discussion

Aedes mosquitoes are responsible for 96 million dengue cases per year. Although the exact mechanisms are unclear, Wolbachia-modified Aedes aegypti mosquitoes prevent the spread of dengue virus through future bites [49, 50], which shows the potential of Wolbachia as a vector-suppression agent. In this study, we assessed the prevalence of Wolbachia in 15 female mosquito species collected from the field in Hainan, China, i.e. Ae. albopictus, Ae. lineatopennis, Ae. vexans, Ar. subalbatus, Cx. quinquefasciatus, Cx. tritaeniorhynchus, Cx. gelidus, An. sinensis, An. campestris, An. crawfordi, An. kochi, An. tessellatus, An. vagus, Ma. uniformis and T. splendens. Wolbachia was detected in four mosquito species. To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive report to illustrate the presence and phylogeny of Wolbachia bacteria in natural mosquito populations in Hainan Province, including Aedes, Culex, Anopheles, Armigeres, Mansonia and Toxorhynchites mosquitoes, detected using Wolbachia wsp, FtsZ and 16S rRNA PCR amplifications. As expected, the highest Wolbachia infection rate was in Ae. albopictus populations. Our results of total Wolbachia infection rate of 36.1% are comparable to those previously reported from neighboring countries such as Singapore (43.9%) [51], Thailand (61.5%) [52] and Malaysia (46.1) [44].

This study for the first time reported sequence variations of Wolbachia strains in Cx. gelidus mosquitoes. Culex gelidus is an emerging mosquito vector in India, Southeast Asia and Australia with the potential to transmit multiple viruses, including Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), chikungunya (CKV), Ross River (RRV), Sindbis, Tembusu, West Nile (WNV), Kunjin and Murray Valley encephalitis viruses [53,54,55]. Wolbachia infections were previously reported in Cx. gelidus in central Thailand [56], while no infection was found in Cx. gelidus in Sri Lanka [57]. Due to the small number of mosquito specimens in this study, further studies are required to examine the distribution and phylogeny of Wolbachia strains in Cx. gelidus.

High genetic diversity of Wolbachia strains was found in Ae. albopictus and Ar. subalbatus, while low sequence variation was detected in Cx. quinquefasciatus. Most of the Ae. albopictus infections were a mixture of type A and type B Wolbachia, while Cx. quinquefasciatus was only infected with type B. Both type A and type B were detected in Ar. subalbatus, while a novel type C (Cx.gelidus-wspH1) was detected in Cx. gelidus mosquitoes. High rates of co-infection with type A and type B Wolbachia in Ae. albopictus have also been reported in other parts of China [27, 28], Argentina [58], Thailand [59] and Malaysia [60]. Co-infection with wAlbA and wAlbB was not observed in the natural population of Cx. quinquefasciatus in this study. In Indonesia, Shih et al. found that about 30% of Cx. quinquefasciatus were infected with group B Wolbachia and < 1% were infected with groups A and A&B [61]. A high proportion of Ar. subalbatus co-infected with wAlbA and wAlbB has been reported in Guangdong Province, China [62]. Studies found that Ar. subalbatus populations were infected with type A Wolbachia in Sri Lanka [57]. These regional variations in mosquito-Wolbachia interactions may represent an ongoing evolving process, or the infections may be occurring by chance or be associated with local environments. Further investigation is warranted.

In this study, we found no Wolbachia-infected Anopheles mosquitoes, including An. sinensis, An. campestris, An. crawfordi, An. kochi, An. tessellatus and An. vagus; this is similar to studies in Thailand [61], Italy [63], the USA [64] and Sri Lanka [57]. A few studies have found Anopheles mosquitoes infected with Wolbachia, such as in Tanzania [65], sub-Saharan Africa [66], Malaysia [44] and Burkina Faso [67]. Experiments on laboratory-reared Anopheles mosquitoes found that infection of Wolbachia in vector did affect the malaria parasite transmission. For example, Bian et al. found that the infection of Anopheles stephensi with Wolbachia wAlb B led to refractoriness to Plasmodium parasite infection [68]. Hughes et al. found that Wolbachia infections are virulent and inhibit the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum's development in Anopheles gambiae [69]. Shaw et al. found that Wolbachia infections in natural populations of Anopheles coluzzii negatively affected Plasmodium development [70]. It is possible that natural Wolbachia infection is variable in different areas; however, natural Wolbachia infection of wild Anopheles species is uncommon. Instances of Wolbachia infection in Anopheles mosquitoes should be further investigated, as previous studies suggest that the variability of strains found in some mosquito species (e.g. Aedes) may be due to environmental contamination rather than true Wolbachia infection [71]. For example, when collecting adult mosquitoes using CDC light traps, both Culex and Anopheles can be captured, and they are mixed (usually crashed) in the collection bag; contamination can occur at this stage—Culex harbors Wolbachia and Anopheles are contaminated.

We must note that the results from this study cannot be compared with experiments for DENV/ZIKV control in Aedes or Culex for WNV. First, the Wolbachia infection prevalence and strains are not comparable between them, because our data are from natural infection of Wolbachia in mosquitoes and the Wolbachia infections for DENV/ZIKV controls in Aedes are artificial (usually 100% prevalence with a uniform combination of strains) [14, 72]. Second, we do not know if the naturally occurring Wolbachia infection is enough to cause CI or blocking DENV/ZIKA/WNV transmission [73]. In addition, there are plenty of studies focusing on Aedes mosquitoes and Aedes transmitted viruses such as dengue, Zika and chikungunya viruses among others [14]. Only one Wolbachia strain is originally isolated from Culex mosquito against West Nile virus, i.e. wPip from Cx. quinquefasciatus [73]. Although the two Ae. aegypti strains of Wolbachia, wAlb B and wMelPop, have been found to be good for Culex infections [74, 75], wMelPop is no longer being considered for field releases because of previous failures [26]. No specific Wolbachia strain has been found to block or reduce Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) infection intensity [76]. Further investigation is desperately needed to study the Wolbachia infections in Culex mosquitoes transmitting WNV and JEV.

The three genetic markers (16S rRNA, FtsZ and wsp genes) have been widely used for characterization and classification of the insect endosymbiotic Wolbachia by single locus or multilocus sequence alignment (MLSA) analysis [45, 52, 77,78,79]. Eight supergroups have been designated (named A to H) primarily based on sequence data from the 16S rRNA, FtsZ and wsp genes [80, 81]. The majority of mosquito endosymbiotic Wolbachia strains belong to supergroups A and B [82]. In the current study, we observed similar results for the classifications of Wolbachia infection by using wsp gene alone or combining the three genes together, indicating a low or similar genetic diversity of FtsZ and 16S rRNA genes compared to wsp genes. Further investigation may be needed using multilocus sequence typing (MLST) of the five genes (FtsZ, fbpA, hcpA, coxA and gatB) to reduce the confounding effect of genetic recombination [83]. MLST method may be more informative compared to sequencing a single marker, thus providing more accurate classifications of Wolbachia strains.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that Wolbachia infections were present in only a few mosquito species in Hainan Province, including the major dengue vector Ae. albopictus. Given the fact that Wolbachia can reduce the lifespan of some of its hosts, prevent certain pathogens from completing their life cycle and reduce the susceptibility of the host to certain pathogen infections, Wolbachia is being released on a small scale in many countries as an alternative vector control agent. The discovery of novel resident Wolbachia strains in local mosquito species in Hainan may also impact future attempts to expand Wolbachia biocontrol strategies for disease prevention. The long-term effects of introducing Wolbachia into new hosts and its effect on pathogen suppression should be thoroughly investigated.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Nucleotide sequences generated in this study have been submitted to GenBank (accession nos. OP279050-OP279063, OP367764-OP367777, OP363894-OP363900, OP393144-OP393149 and OP426265-OP426271).

References

Hilgenboecker K, Hammerstein P, Schlattmann P, Telschow A, Werren JH. How many species are infected with Wolbachia?–a statistical analysis of current data. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;281:215–20.

Duron O, Bouchon D, Boutin S, Bellamy L, Zhou L, Engelstadter J, et al. The diversity of reproductive parasites among arthropods: Wolbachia do not walk alone. BMC Biology. 2008;6:27.

Kozek WJ, Rao RU. The discovery of Wolbachia in arthropods and nematodes—a historical perspective. Issues in Infectious Diseases. 2007;5:1–14.

Ferri E, Bain O, Barbuto M, Martin C, Lo N, Uni S, et al. New insights into the evolution of Wolbachia infections in filarial nematodes inferred from a large range of screened species. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:20843.

Landmann F. The Wolbachia endosymbionts. Microbiol Spectr. 2019;7:111.

Zug R, Hammerstein P. Still a host of hosts for Wolbachia: analysis of recent data suggests that 40% of terrestrial arthropod species are infected. PloS ONE. 2012;7:e38544.

Werren JH, Baldo L, Clark ME. Wolbachia: master manipulators of invertebrate biology. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:741–51.

Jiggins FM, Hurst GDD, Majerus MEN. Sex ratio distortion in Acraea encedon (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) is caused by a male-killing bacterium. Heredity. 1998;81:87–91.

Weeks AR, Breeuwer JA. Wolbachia-induced parthenogenesis in a genus of phytophagous mites. Proc Biol Sci. 2001;268:2245–51.

Moretti R, Calvitti M. Male mating performance and cytoplasmic incompatibility in a wPip Wolbachia trans-infected line of Aedes albopictus (Stegomyia albopicta). Med Vet Entomol. 2013;27:377–86.

van den Berg H, da Silva Bezerra HS, Al-Eryani S, Chanda E, Nagpal BN, Knox TB, et al. Recent trends in global insecticide use for disease vector control and potential implications for resistance management. Sci Rep. 2021;11:23867.

Hemingway J, Field L, Vontas J. An overview of insecticide resistance. Science. 2002;298:96–7.

Liu N. Insecticide resistance in mosquitoes: impact, mechanisms, and research directions. Annu Rev Entomol. 2015;60:537–59.

Ross PA. Designing effective Wolbachia release programs for mosquito and arbovirus control. Acta Trop. 2021;222:106045.

Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Walker T, ONeill SL. Wolbachia and the biological control of mosquito-borne disease. Embo Rep. 2011;12:508–18.

Zheng X, Zhang D, Li Y, Yang C, Wu Y, Liang X, et al. Incompatible and sterile insect techniques combined eliminate mosquitoes. Nature. 2019;572:56–61.

National Environment Agency. Wolbachia-Aedes mosquito suppression strategy. https://www.nea.gov.sg/corporate-functions/resources/research/wolbachia-aedes-mosquito-suppression-strategy. Accessed 29 Mar 2021.

Beebe NW, Pagendam D, Trewin BJ, Boomer A, Bradford M, Ford A, et al. Releasing incompatible males drives strong suppression across populations of wild and Wolbachia-carrying Aedes aegypti in Australia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118:2106828118.

Crawford JE, Clarke DW, Criswell V, Desnoyer M, Cornel D, Deegan B, et al. Efficient production of male Wolbachia-infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes enables large-scale suppression of wild populations. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38:482–92.

Mains JW, Brelsfoard CL, Rose RI, Dobson SL. Female adult Aedes albopictus suppression by Wolbachia-infected male mosquitoes. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33846.

Moretti R, Marzo GA, Lampazzi E, Calvitti M. Cytoplasmic incompatibility management to support incompatible insect technique against Aedes albopictus. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:649.

Bian G, Xu Y, Lu P, Xie Y, Xi Z. The endosymbiotic bacterium Wolbachia induces resistance to dengue virus in Aedes aegypti. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000833.

Walker T, Johnson PH, Moreira LA, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Frentiu FD, McMeniman CJ, et al. The wMel Wolbachia strain blocks dengue and invades caged Aedes aegypti populations. Nature. 2011;476:450–3.

Bian G, Xu Y, Lu P, Xie Y, Xi Z. The endosymbiotic bacterium Wolbachia induces resistance to dengue virus in Aedes aegypti. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000833.

Ant TH, Mancini MV, McNamara CJ, Rainey SM, Sinkins SP. Wolbachia-Virus interactions and arbovirus control through population replacement in mosquitoes. Pathog Glob Health. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/20477724.2022.2117939.

Nguyen TH, Nguyen HL, Nguyen TY, Vu SN, Tran ND, Le TN, et al. Field evaluation of the establishment potential of w MelPop Wolbachia in Australia and Vietnam for dengue control. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:563.

Hu Y, Xi Z, Liu X, Wang J, Guo Y, Ren D, et al. Identification and molecular characterization of Wolbachia strains in natural populations of Aedes albopictus in China. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13:28.

Zhang D, Zhan X, Wu X, Yang X, Liang G, Zheng Z, et al. A field survey for Wolbchia and phage WO infections of Aedes albopictus in Guangzhou City China. Parasitol Res. 2014;113:399–404.

Wiwatanaratanabutr I, Zhang C. Wolbachia infections in mosquitoes and their predators inhabiting rice field communities in Thailand and China. Acta Trop. 2016;159:153–60.

Wei S, Lin S, Yang C. The 50-year history of the development of health in Hainan Province. Haikou: Southern Press; 2007.

Li S, Jiang F, Lu H, Kang X, Wang Y, Zou Z, et al. Mosquito diversity and population genetic structure of six mosquito species from Hainan Island. Front Genet. 2020;11:602863.

Li Y, Zhou G, Zhong S, Wang X, Zhong D, Hemming-Schroeder E, et al. Spatial heterogeneity and temporal dynamics of mosquito population density and community structure in Hainan Island China. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13:444.

Du J, Zhang L, Hu X, Peng R, Wang G, Huang Y, et al. phylogenetic analysis of the dengue virus strains causing the 2019 dengue fever outbreak in Hainan China. Virol Sin. 2021;36:636–43.

Liu L, Wu T, Liu B, Nelly RMJ, Fu Y, Kang X, et al. The origin and molecular epidemiology of dengue fever in Hainan Province, China, 2019. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:657966.

Dong X, Zhou H, Gong Z. The mosquito fauna of Yunnan. Yunnan: Yunnan Science & Technology Press; 2010.

Chang X, Zhong D, Li X, Huang Y, Zhu G, Wei X, et al. Analysis of population genetic structure of Anopheles sinensis based on mitochondrial DNA cytochrome oxidase subunit I gene fragment. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2015;35:47.

Joshi D, Park MH, Saeung A, Choochote W, Min GS. Multiplex assay to identify Korean vectors of malaria. Mol Ecol Res. 2010;10:748–50.

Diaz-Badillo A, Bolling BG, Perez-Ramirez G, Moore CG, Martinez-Munoz JP, Padilla-Viveros AA, et al. The distribution of potential West Nile virus vectors, Culex pipiens pipiens and Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae), in Mexico City. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:70.

Bargielowski IE, Lounibos LP, Shin D, Smartt CT, Carrasquilla MC, Henry A, et al. Widespread evidence for interspecific mating between Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in nature. Infect Genet Evol. 2015;36:456–61.

Folmer O, Black M, Hoeh W, Lutz R, Vrijenhoek R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol Mar Biol Biotechnol. 1994;3:294–9.

Zhou W, Rousset F, O’Neil S. Phylogeny and PCR-based classification of Wolbachia strains using wsp gene sequences. Proc Biol Sci. 1998;265:509–15.

Shaw WR, Marcenac P, Childs LM, Buckee CO, Baldini F, Sawadogo SP, et al. Wolbachia infections in natural Anopheles populations affect egg laying and negatively correlate with Plasmodium development. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11772.

Werren JH, Windsor DM. Wolbachia infection frequencies in insects: evidence of a global equilibrium? Proc Biol Sci. 2000;267:1277–85.

Wong ML, Liew JWK, Wong WK, Pramasivan S, Mohamed Hassan N, Wan Sulaiman WY, et al. Natural Wolbachia infection in field-collected Anopheles and other mosquito species from Malaysia. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13:414.

Sarwar MS, Jahan N, Shahbaz F. Molecular detection and characterization of Wolbachia pipientis from Culex quinquefasciatus collected from Lahore Pakistan. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;98:154–61.

Guo Y, Song Z, Luo L, Wang Q, Zhou G, Yang D, et al. Molecular evidence for new sympatric cryptic species of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in China: A new threat from Aedes albopictus subgroup? Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:228.

Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser. 1999;41:95–8.

Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35:1547–9.

Turley AP, Moreira LA, O’Neill SL, McGraw EA. Wolbachia infection reduces blood-feeding success in the dengue fever mosquito. Aedes aegypti PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;9:e516.

Ong S. Wolbachia goes to work in the war on mosquitoes. Nature. 2021;598:S32–4.

Ding H, Yeo H, Puniamoorthy N. Wolbachia infection in wild mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae): implications for transmission modes and host-endosymbiont associations in Singapore. Parasit Vect. 2020;13:612.

Kittayapong P, Baisley KJ, Baimai V, O’Neill SL. Distribution and diversity of Wolbachia infections in Southeast Asian mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol. 2000;37:340–5.

Sudeep AB. Culex gelidus: an emerging mosquito vector with potential to transmit multiple virus infections. J Vect Borne Dis. 2014;51:251–8.

Garjito TA, Prihatin MT, Susanti L, Prastowo D, Sa’adah SR, Taviv Y, et al. First evidence of the presence of genotype-1 of Japanese encephalitis virus in Culex gelidus in Indonesia. Parasit Vect. 2019;12:19.

Sudeep AB, Ghodke YS, George RP, Ingale VS, Dhaigude SD, Gokhale MD. Vectorial capacity of Culex gelidus (Theobald) mosquitoes to certain viruses of public health importance in India. J Vector Borne Dis. 2015;52:153–8.

Tiawsirisup S, Sripatranusorn S, Oraveerakul K, Nuchprayoon S. Distribution of mosquito (Diptera: Culicidae) species and Wolbachia (Rickettsiales: Rickettsiaceae) infections during the bird immigration season in Pathumthani province, central Thailand. Parasitol Res. 2008;102:731–5.

Nugapola N, De Silva W, Karunaratne S. Distribution and phylogeny of Wolbachia strains in wild mosquito populations in Sri Lanka. Parasit Vect. 2017;10:230.

Chuchuy A, Rodriguero MS, Ferrari W, Ciota AT, Kramer LD, Micieli MV. Biological characterization of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in argentina: implications for arbovirus transmission. Sci Rep. 2018;8:5041.

Kitrayapong P, Baimai V, O’Neill SL. Field prevalence of Wolbachia in the mosquito vector Aedes albopictus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;66:108–11.

Noor Afizah A, Roziah A, Nazni WA, Lee HL. Detection of Wolbachia from field collected Aedes albopictus Skuse in Malaysia. Indian J Med Res. 2015;142:205–10.

Shih CM, Ophine L, Chao LL. Molecular detection and genetic identification of Wolbachia endosymbiont in wild-caught Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae) mosquitoes from sumatera utara Indonesia. Microb Ecol. 2021;81:1064–74.

Yang D, Ni W, Lai Q, Wang J, Zheng X. Phylogenetic analysis of Wolbachia infection in different mosquito species from different habitats in Guangzhou. Mod Prevent Med. 2019;46:2542–6.

Ricci I, Cancrini G, Gabrielli S, D’Amelio S, Favi G. Searching for Wolbachia (Rickettsiales: Rickettsiaceae) in mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae): large polymerase chain reaction survey and new identifications. J Med Entomol. 2002;39:562–7.

Rasgon JL, Scott TW. An initial survey for Wolbachia (Rickettsiales: Rickettsiaceae) infections in selected California mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol. 2004;41:255–7.

Baldini F, Rouge J, Kreppel K, Mkandawile G, Mapua SA, Sikulu-Lord M, et al. First report of natural Wolbachia infection in the malaria mosquito Anopheles arabiensis in Tanzania. Parasit Vect. 2018;11:635.

Jeffries CL, Lawrence GG, Golovko G, Kristan M, Orsborne J, Spence K, et al. Novel Wolbachia strains in Anopheles malaria vectors from Sub-Saharan Africa. Wellcome Open Res. 2018;3:113.

Baldini F, Segata N, Pompon J, Marcenac P, Shaw WR, Dabire RK, et al. Evidence of natural Wolbachia infections in field populations of Anopheles gambiae. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3985.

Bian G, Joshi D, Dong Y, Lu P, Zhou G, Pan X, et al. Wolbachia invades Anopheles stephensi populations and induces refractoriness to Plasmodium infection. Science. 2013;340:748–51.

Hughes GL, Koga R, Xue P, Fukatsu T, Rasgon JL. Wolbachia infections are virulent and inhibit the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum in Anopheles gambiae. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002043.

Shaw WR, Marcenac P, Childs LM, Buckee CO, Baldini F, Sawadogo SP, et al. Wolbachia infections in natural Anopheles populations affect egg laying and negatively correlate with Plasmodium development. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11772.

Ross PA, Callahan AG, Yang Q, Jasper M, Arif MAK, Afizah AN, et al. An elusive endosymbiont: does Wolbachia occur naturally in Aedes aegypti? Ecol Evol. 2020;10:1581–91.

Ant TH, Herd C, Louis F, Failloux AB, Sinkins SP. Wolbachia transinfections in Culex quinquefasciatus generate cytoplasmic incompatibility. Insect Mol Biol. 2020;29:1–8.

Glaser RL, Meola MA. The native Wolbachia endosymbionts of Drosophila melanogaster and Culex quinquefasciatus increase host resistance to West Nile virus infection. PloS ONE. 2010;5:11977.

Joubert DA, O’Neill SL. Comparison of stable and transient Wolbachia infection models dirk albert in Aedes aegypti to block dengue and west nile viruses. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005275. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0005275.

Hussain M, Lu G, Torres S, Edmonds JH, Kay BH, Khromykh AA, et al. Effect of Wolbachia on replication of West Nile virus in a mosquito cell line and adult mosquitoes. J Virol. 2013;87:851–8.

Jeffries CL, Walker T. The potential use of Wolbachia-based mosquito biocontrol strategies for Japanese Encephalitis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003576. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0003576.

de Oliveira CD, Gonçalves DS, Baton LA, Shimabukuro PH, Carvalho FD, Moreira LA. Broader prevalence of Wolbachia in insects including potential human disease vectors. Bull Entomol Res. 2015;105:305–15.

Chai HN, Du YZ, Qiu BL, Zhai BP. Detection and phylogenetic analysis of Wolbachia in the Asiatic rice leafroller, Cnaphalocrocis medinalis, in Chinese populations. J Insect Sci. 2011;11:123.

Pina T, Sabater-Muñoz B, Cabedo-López M, Cruz-Miralles J, Jaques JA, Hurtado-Ruiz MA. Molecular characterization of Cardinium, Rickettsia, Spiroplasma and Wolbachia in mite species from citrus orchards. Exp Appl Acarol. 2020;81:335–55.

Lo N, Casiraghi M, Salati E, Bazzocchi C, Bandi C. How many wolbachia supergroups exist? Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19:341–6.

Werren JH, Baldo L, Clark ME. Wolbachia: master manipulators of invertebrate biology. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:741–51.

Inácio da Silva LM, Dezordi FZ, Paiva MHS, Wallau GL. Systematic review of Wolbachia Symbiont detection in mosquitoes: an entangled topic about methodological power and true symbiosis. Pathogens. 2021;10:39.

Baldo L, Dunning Hotopp JC, Jolley KA, Bordenstein SR, Biber SA, Choudhury RR, et al. Multilocus sequence typing system for the endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:7098–110.

Acknowledgements

We thank Xianchuan Shen, Xiansong Bian and Dajian Su for their assistance with the field mosquito collection.

Funding

This study was supported by Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation (820RC653), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82060379), Major Science and Technology Program of Hainan Province (ZDKJ202003), Research Project of Hainan Academician Innovation Platform (YSPTZX202004), the Talent Introduction Fund of Hainan Medical University (XRC220012), the Open Foundation of NHC Key Laboratory of Tropical Disease Control, Hainan Medical University (2022NHCTDCKFKT31002), Hainan Province Clinical Medical Center and the National Institutes of Health of the US (U19 AI089672 and U19 AI129326).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Primers for amplification and sequencing.

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Mosquito diversity among the five study areas in Hainan Province, China.

Additional file 3: Table S3.

Infection status of Wolbachia based on PCR results of field-collected Aedes albopictus adults.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Sun, Y., Zou, J. et al. Characterizing the Wolbachia infection in field-collected Culicidae mosquitoes from Hainan Province, China. Parasites Vectors 16, 128 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-023-05719-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-023-05719-y