Abstract

Background

Biological controls with predators of larval mosquito vectors have historically focused almost exclusively on insectivorous animals, with few studies examining predatory plants as potential larvacidal agents. In this study, we experimentally evaluate a generalist plant predator of North America, Utricularia macrorhiza, the common bladderwort, and evaluate its larvacidal efficiency for the mosquito vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in no-choice, laboratory experiments. We sought to determine first, whether U. macrorhiza is a competent predator of container-breeding mosquitoes, and secondly, its predation efficiency for early and late instar larvae of each mosquito species.

Methods

Newly hatched, first-instar Ae. albopictus and Ae. aegypti larvae were separately exposed in cohorts of 10 to field-collected U. macrorhiza cuttings. Data on development time and larval survival were collected on a daily basis to ascertain the effectiveness of U. macrorhiza as a larval predator. Survival models were used to assess differences in larval survival between cohorts that were exposed to U. macrorhiza and those that were not. A permutation analysis was used to investigate whether storing U. macrorhiza in laboratory conditions for extended periods of time (1 month vs 6 months) affected its predation efficiency.

Results

Our results indicated a 100% and 95% reduction of survival of Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus larvae, respectively, in the presence of U. macrorhiza relative to controls within five days, with peak larvacidal efficiency in plant cuttings from ponds collected in August. Utricularia macrorhiza cuttings, which were prey-deprived, and maintained in laboratory conditions for 6 months were more effective larval predators than cuttings, which were maintained prey-free for 1 month.

Conclusions

Due to the combination of high predation efficiency and the unique biological feature of facultative predation, we suggest that U. macrorhiza warrants further development as a method for larval mosquito control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The control of larval mosquitoes with predators and other biological agents has been widely recognized as a promising strategy that can reduce negative environmental impacts associated with chemical control [1, 2]. Several diverse animal taxa have been explored as biological controls of larval mosquitoes including larvivorous fish, amphibians, and aquatic insects such as odonates and even larvae of certain mosquito species [3]. The advantages and disadvantages to each predator species are a function of prey specificity, larvacidal efficiency, and ease of management of applications for sustained periods and across the various habitats of mosquito vector species [4, 5].

Larvivorous fish have successfully controlled larvae in the genus Anopheles in a variety of habitats worldwide [6,7,8,9,10,11], though they have been less successful in the control of Aedes species [12]. This success is largely attributed to the high predation rates of species such as the mosquito fish, Gambusia affinis and G. holbrooki [13]. The disadvantage of mosquito fish is that with repeated introductions to aquatic habitats for mosquito control, there has been little consideration of their impacts on the ecosystem [14], and they have become invasive in pristine aquatic habitats [15]. Invasive mosquito fish impact native fish through indirect competition for resources [15,16,17,18] and direct competition by biting [19]. Other species of catfish have been assessed in domestic water containers with high demonstrated larvacidal efficacy for Aedes mosquitoes [20]. Domestic containers are not sustainable habitat for these fish and they must be replenished, a limitation of the overall feasibility of larvivorous fish for sustained control [5].

There are several options for arthropod predator controls of mosquito larvae that have been explored. Mosquitoes of the genus Toxorhynchites have been identified as predators of other larvae [21]. Their distribution largely overlaps with that of Aedini disease vectors [22, 23] and they colonize otherwise cryptic breeding sites that are difficult to reach for control. Field applications demonstrate limited success [24, 25] or even have resulted in an increase in prey density [26,27,28]. Releases of nymphal dragonflies and damselflies of Odonata as alternative predators have had mixed success [29, 30]. Unlike Toxorhynchites [19], odonates are generalists and can cover a wide range of habitats [31,32,33]. Past studies have reported promising predation rates [34,35,36] even in container habitats [37]. Similarly, copepods of the genus Mesocylops have shown promising results with regards to control of the yellow fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti). In Vietnam, community-involved releases have resulted in local eradications of Ae. aegypti from 40 non-urban communities [38, 39]. Overall however, successful applications of odonates and copepods are limited in number in part because of the difficulty in maintaining large stocks capable of supporting repeated releases in order to sustain biological control [3, 38, 40,41,42,43].

Amphibian tadpoles have demonstrated high larvacidal efficiency, although their predatory efficiency of mosquito larvae has not been estimated in the presence of alternative prey sources [5]. Several disadvantages to tadpoles for biocontrol of Aedes species have been noted, including low survival in small containers, the influence they exert on ecosystems, and the caution needed when considering introductions either in the low likelihood of success or in introducing an invasive species.

An understudied predator-prey association that merits exploration for biological control is that between aquatic plants in the genus Utricularia and mosquito larvae (Fig. 1a–c). Darwin & Darwin [44] first described the ability of Utricularia vulgaris to capture and asphyxiate insect larvae using lentil-shaped bladders. Bladderworts have been described as effective suction feeders of a variety of zooplankton, rotifers, protozoans, Daphnia and even small fish fry [45]. The biological control properties of the plant were noted and described by Matheson [45] and Twinn [46]. Despite this, the application of bladderworts as a biological control of mosquito larvae has been relatively unrecognized and understudied in recent years. Recent reviews of biological control tools for mosquito larvae excluded Utricularia [47] even when focusing on control with larvacidal predators [5] or alternative strategies [48]. Estimates of predation capabilities of bladderworts for mosquito larva are limited, with a notable exception. Utricularia macrorhiza (commonly referred to as U. vulgaris in North American’s literature prior to Taylor [49]) was observed to have high rates of predation on Culex pipiens larvae, ranging between 50–100% [50]. It has since been suggested that using bladderwort as a biological control strategy may be of limited value because of the abundance of alternative prey sources in the natural habitats of Culex pipiens [50,51,52]. These studies have centered on mosquito species that develop in permanent and temporary pools with large volumes of water. There is evidence to suggest that several Utricularia predators may thrive outside of their natural habitat [46, 50, 53, 54], and thus may be applied to the control of container-breeding species.

Utricularia macrorhiza is pictured maintained indoors in small containers in a close up view of a single bladder with trap chamber and trigger appendages labeled (a), expanded view of the plant cutting (b) and with Utricularia macrorhiza close up with bladders on stems digesting Aedes aegypti larvae indicated with red asterisks (c)

Utricularia macrorhiza is widely distributed in North America [55] but has yet to be explored in small water containers such as those utilized by Aedes mosquitoes for larval development. In this study, we explore the potential for aquatic bladderworts in the genus Utricularia (Lentibulariaceae) as predators of Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus. These species have a habitat preference for small man-made containers that are naturally prey-limited [12, 56,57,58], and this preference has been a driving feature of their expansion through urban areas [59, 60].

We first sought to determine if plant cuttings could survive when displaced from their natural habitats for lengthy periods of time and placed in small man-made containers typically inhabited by Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus mosquitoes. We hypothesized that U. macrorhiza would readily predate mosquito larvae regardless of species and larval stage, and effectively reduce mosquito laboratory populations through direct impacts on survival during the larval stages. We tested this hypothesis in no-choice, laboratory rearing experiments, and estimated daily predation efficiency of plant cuttings of standardized bladder density.

Both Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus are historically and currently important vectors of pathogens including dengue, yellow fever, Zika and chikungunya viruses [61, 62], and although few autochthonous cases have been noted recently in their USA range, the distribution and abundance of these vectors is resurging in recent years [63]. The rise of insecticide resistance in natural mosquito populations [64, 65], combined with the discovery of non-target effects of chemical pesticides on other species, including humans [66,67,68] underscores the need to develop alternative, eco-friendly strategies for the management strategies for these vectors.

Methods

Mosquito colony conditions

Laboratory colonies of Ae. aegypti strain originating from Puerto Rico and Ae. albopictus colony, originating from New Orleans, LA, were maintained at 27 °C, 75% RH, with a 16:8 L:D photoperiod. Experimental larvae were hatched from the laboratory colony from generations F10-F18 and placed in experimental conditions within 24 h of hatching.

Bladderwort collection/cultivation

Common bladderwort (U. macrorhiza) was collected throughout the spring, summer and fall seasons of 2017 from 6 freshwater ponds in South Kingstown, RI, USA (Fig. 2). The presence of other species in the genus Utricularia was noted for each pond. Whole plants and segments of approximately 30–45 cm in length were sampled from the edges of ponds by hand and transported in water to the laboratory. Strands of U. macrorhiza were checked and cleared of symbiotic odonates. Plants were placed in container-tubs and left to acclimate to laboratory conditions (at room temperature) for a minimum of a month before being used for experimentation. Bladderworts continuously grow bladders, which become active and decay. A constant number of bladders was therefore not feasible, but strands were chosen for the experimental period which has approximately 100 bladders in order to start the experiments with an initial bladder to larva ratio of 10:1.

Predation of container-dwelling mosquitoes by U. macrorhiza

Experimental eggs were hatched in Picotap-filtered water by multiple-immersion clue. Eggs were briefly submerged and dried for three times prior to hatching to simulate oxygen fluctuation that would be typical under field conditions. We examined the survival rates of container-dwelling mosquitoes in the presence of predating U. macrorhiza under the conditions of 10 larvae per 500 ml of Picotap-filtered water with a 15-cm-long segment of U. macrorhiza with approximately 100 bladders. We recorded the survival status and developmental stage of each individual on a daily basis until death or emergence occurred. Larvae were fed every-other-day with finely ground and sieved fish-food (TetraMin Tropical Flakes, Tetra, Melle, Germany). Food was added on a per-capita basis to each cup [69] such that larvae were provided 0.06 mg/larva on day 1, 1.0 mg/larva on day 3, 1.5 mg/larva on day 5, and 1.8 mg/larva on day 7. Upon emergence, adults were transferred into 2.0 ml microcentrifuge tubes and stored at − 30 °C.

Fourteen replicates were conducted with Ae. aegypti larvae and plant cuttings that had been without prey for one month. Four additional replicates were conducted with Ae. aegypti with cuttings that had been stored in open containers in a windowsill indoors at ambient room conditions without availability of prey for 6 months. Twenty replicates were conducted for Ae. albopictus using cuttings of U. macrorhiza that had been stored 6 months without prey. Because the period without prey is known to alter the number of bladder traps in several species of Utricularia [70,71,72,73], we separated replicates based on the number of months the plants had been stored. However, the initial number of bladders used in experimental cups was standardized to 100 bladders. Therefore, differences observed between 1-month replicates and 6-month replicates are attributed to differences in bladder trapping activity rather than the number of bladders. For each replicate, the number of bladders per U. macrorhiza segment was measured less than 24 h before set-up. The cause of larval mortality was attributed to direct predation when larvae were found wholly or partially inside of bladders. When larvae were found dead outside of bladders cause of death was not noted. The experiment concluded when all U. macrorhiza exposed larvae either died or emerged.

We investigated whether U. macrorhiza, under similar laboratory conditions as previous experiments, was able to predate third- and fourth-instar Ae. aegypti larvae. We placed 8 replicates of ten larvae that were initially third-instar to U. macrorhiza segments. Over the course of the experiment several larvae molted to fourth-instar. After 24 h we recorded total survival and life stage. The aim of this experiment was to assess whether bladders were capable of trapping larger prey. Bladder size is highly variable even within U. macrorhiza. We estimated bladder traps used in this experiment to range from 2–4 mm in width.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted in RStudio v.1.0.143 [74] using the survival package v.2.42-6 [75]. We estimated the effects that exposure to U. macrorhiza had on mosquito survival using the Cox-proportional Hazard model with an Efron approximation and Weibull function [76]. The assumption of proportional hazard was tested using Schoenfeld’s residual test [77]. Bladders predate to satiation and thus their ability to impact mosquito survival is implicitly linked with time. Thus, it was expected that these data would violate the assumption of proportional hazard. While the Mantel-Cox logrank test [78] is the most commonly used statistical method of comparison for survival curves, its usage becomes unsuitable when the hazard ratio does not remain proportional with time, as these data suggested. To account for this violation of the assumption of proportionality with the Mantel-Cox test, we instead used the non-parametric Peto & Peto modification of the Gehan-Wilcoxon test. This method remains robust even when the assumption of proportional hazard is violated [79].

Results

Aedes albopictus replicates exposed to plant predation showed a greater Cox proportional hazard than controls (Fig. 3a; Likelihood ratio test: 239.9, df = 1, P < 0.0001). There was sufficient mortality in control cups, which developed in the absence of predators, to develop Cox proportional hazard estimates (HR = 9.812, CI: 7.06–13.66, P < 2 × 10−16). In cups with the plant predator an average of 71.5% of larvae died within the first 24 h. Over the course of the next four days larvae continued to be preyed upon, with 16% of larvae dying on the second day, 4.5% dying on the third day, 1.5% dying on the fourth day, and a further 1.5% dying on the fifth day. By the end of the fifth day, 95% of all larvae coexisting with U. macrorhiza had died. No further deaths due to predation occurred past the fifth day. Out of the surviving individuals (n = 10), all but one originated from the same experimental container. A non-parametric test of survival hazards comparing predation in experimental cups versus treatments cups shows that predation by U. macrorhiza significantly reduced larval survival (χ2 = 209, df = 1, P < 1 × 10−16).

Survival probability over time (in days) of Ae. albopictus (a) and Ae. aegypti (b) in the presence and absence of U. macrorhiza stored without prey for six months. Dotted lines represent water-only controls. Solid lines represent experimental cups with U. macrorhiza. Black indicates plants were stored for 1 month without prey and green indicates plants were stored for 6 months without prey. For both figures, data are censored as of the day when the last death from predation by U. macrorhiza was observed

Similarly, the presence of the plant predator was found to significantly reduce Ae. aegypti survival under laboratory conditions (χ2 = 308, df = 3, P < 1 × 10−16, Fig. 1c). Across all replicates, the average predation efficiency was highest during the first 24 h, during which, 83.1% of larvae were found consumed within bladder traps. Within 48 h 95.5% of larvae were preyed upon. On days three and four 97.7% and 99.4% of larvae were preyed upon, respectively (Fig. 3b). By day 5 all larvae within cups with a plant predator were consumed. Having been placed within 24 h of hatching, the latest developmental stage achieved by Ae. aegypti larvae in the presence of predating U. macrorhiza was the second instar.

In addition to comparing treatments with and without the plant predator, we considered the number of months that plant cuttings sat without prey. Table 1 presents the results of a permutation model of Ae. aegypti larval survival that accounts for both the time plant cuttings were stored without prey (one month or six months) and treatment (presence or absence of predator) which significantly improved prediction of larval survival probability over a model of treatment alone (F(1, 356) = 25.03, P < 8.87 × 10−7).

A further experiment was conducted to determine whether U. macrorhiza was capable of preying upon third-instar (Additional file 1: Video 1) and fourth-instar (Additional file 2: Video 2) Ae. aegypti larvae. Eight replicates of 10 larvae each were placed into containers with U. macrorhiza. After 24 h the predation efficiency was variable from 60 to 100% consumed, demonstrating that plant predatory bladders were capable of consuming later instars (mean ± SE, 77.5 ± 4.91%).

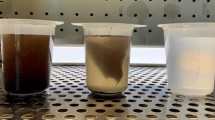

We carried out predation experiments with small cuttings of U. macrorhiza measuring approximately 1.25 cm, with one bladder and placed into the well of a 6-well cell-culture plate with 10 ml of water. We pre-fed the bladder with one larva and counted the number of replicates which predated a second larva of Ae. aegypti or Ae. albopictus over the course of the experiment. We found that larval environments with small cuttings of U. macrorhiza with even a single bladder can effectively reduce larval survival relative to conditions without the plant present (Fig. 4a, b). We also found that a one bladder under these conditions can potentially hold up 3 larvae (Fig. 4c).

Survival probability over time (in days) of Ae. albopictus (a) or Ae. aegypti (b) with small cuttings of U. macrorhiza with two bladders placed in 10 ml of dH20. Pre-fed signifies that bladders were provided one larva of the respective species just prior to the start of the experiment. Image of the experimental set up with the U. macrorhiza cutting having consumed 3 larvae consecutively (heads visible as black dots inside bladder) (c)

Discussion

In this study we evaluated the predation efficiency of U. macrorhiza in two medically important species of Aedes mosquitoes, finding drastic and effective reduction of daily survival for Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus larvae in no-choice predation experiments. The effective control of larval population for both Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus, suggests that U. macrorhiza is a viable option to explore for biocontrol of container-breeding mosquitoes even in small water volumes. Although U. macrorhiza survival and growth were not formally measured under prolonged laboratory conditions, through this study, we determined that the plant is a capable predator of mosquito larvae even after six months after displacement from its original habitat.

We found U. macrorhiza to be capable of preying on first- through third-instar Ae. aegypti larvae. These results are in line with previously published work [80], which suggested that U. macrorhiza can predate mosquitoes at three stages of development. These results were consistent when repeated at smaller water volumes. In comparison to the predation experiments at larger volumes, the survival of larvae exposed to a single bladder on small cuttings of U. macrorhiza is at first glance reduced. However, the bladder to larva ratio in the latter experiment was 1:1, whereas the previous experiments had a ratio of 10:1. While control of larvae at such small water volumes is impractical, these results demonstrate that small water volume is not on its own a limiting factor in the application of U. macrorhiza.

It is possible that U. macrorhiza is capable of effectively preying upon Aedes pupae or large fourth instars; however, the trap sizes observed under laboratory conditions were smaller than those initially collected in the field. As the metamorphic stage, pupae do not forage for food and thus might not interact as frequently with bladders as foraging larvae. However, we expect that fourth instars would be susceptible to U. macrorhiza predation. We observed in third instars that although bladders did not wholly consume them, they were trapped by the siphon, resulting in asphyxiation. Previous work on bladderworts shows that trap size and the ability of the bladders to capture prey is largely dependent on nutrient availability [46, 81,82,83,84]. Predation efficiency on larger prey, including fourth instars likely depends upon the environmental conditions in which it is being measured [80, 85].

Angerilli & Beirne [86] explored another Utricularia species, Utricularia minor, finding similar results that the plant is capable of eliminating Ae. aegypti larvae within 6 days of exposure under artificial container conditions. We found that larval Ae. aegypti were eliminated within four days of exposure to U. macrorhiza, which suggests while there may be some variation between plant species in predation efficiency, there is potential for applying several species within Utricularia to biological control of Ae. aegypti. Similarly, Ae. albopictus larvae were eliminated by day 5. There was one replicate exception for Ae. albopictus, a cup in which U. macrorhiza preyed on only 10% of developing larvae. We attribute the low survival in this replicate to the readily observable poor quality of the cutting used, with greater numbers of senescent bladders. Senescent bladders are known to continue to photosynthesize but do not fire as often or effectively capture prey [87]. Bladders regularly are produced and senesce on cuttings; it is unclear why, but we observed this replicate lost many bladders in the course of the experimental period. The experimental results showed some differences in predation between the two species considered (Fig. 3). Notably, plant predation was sufficient to eliminate larvae prior to the number of days typically needed for larvae to complete larval development.

Bladderworts can exist for extended periods without prey, adaptively shift to carnivory, and increase predatory efficiency as prey density increases. When plants are maintained in the absence of prey for long periods, it can impact the number of bladders [70,71,72,73]. Englund & Harms [88] demonstrated that the investment in predatory biomass (bladders) increases at high prey densities. Subsequently as prey populations dwindle with predation, nutrient enrichment in the plant results in a shift away from carnivory and toward photosynthesis. Indeed, bladderworts exhibit the highest rates of photosynthesis among submerged plants [89]. This suggests that long-term maintenance of nutrient poor conditions is essential to stimulate bladder production [90]. Our results indicated that extended periods without prey did not negatively impact the ability of all but one experimental cup to predate larvae of Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus. Facultative predation, and plasticity in energy allocation toward different growth strategies differentiates bladderworts from other animal predators currently in use for biological control. While not all oviposition sites of Ae. aegypti or Ae. albopictus will be practical or appropriate for control by a photosynthetic plant, we expect U. macrorhiza to be appropriate for a variety of sunlit water storage vessels which individuals are unable or unwilling to empty.

It is possible that bladderworts may be used alongside other chemical and biological control tools. Bladderworts have not yet been explored in conjunction with other control agents, but have been found to be highly resistant to certain insecticides, pesticides and herbicides [91,92,93]. Bladderworts are not expected to be vulnerable to the most commonly deployed larvacidal biological control measures, Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis (Bti) or Bacillus sphaericus, due the bacteria’s specificity to larvae of some Diptera [94, 95]. Indeed, water pools containing Utricularia plants are preferred as oviposition sites by damselflies and other mosquito predators [96, 97], suggesting that introducing Utricularia into novel containers may indirectly affect mosquito populations by aiding the natural predators of container-breeders to establish in these otherwise cryptic environments [98,99,100,101,102,103,104]. These results suggest the potential for bladderworts to be useful and merit further experiments to explore the impacts of combination with other biological control methods.

The effectiveness of a predatory biological control agent depends on a variety of factors that include the biological features of predators and predation efficiency as well as aspects of the management of stocks for biocontrol applications. Biological features relevant to control of larvae include habitat overlap, prey specificity, predatory efficiency, and population dynamics and auto-reproduction. Feasible management of predator populations for biological control include ease of growing and maintaining stock, overlap in distribution between predator and prey and survival in prey habitats, auto-reproduction for sustained control, and the cost-effectiveness of the biocontrol measure [105]. One advantage of aquatic bladderworts as a biocontrol is their extended period of efficacy. Previous field experiments have found various Utricularia plants to be effective at controlling macro-invertebrate preys throughout the summer season [106]. The plants are most predacious in July and August [106], suggesting that their main period of efficacy coincides with that of multivoltine mosquito vectors [107, 108]. The synchrony in seasonality between aquatic bladderworts and mosquito vectors suggests that early releases of the plants may be sufficient to inhibit the development of vectors within accessible container habitats during peak season. In contrast, applications of other common biocontrol measures such as Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis, Toxorhynchites, or odonates generally require two or more seasonal applications to be effective [43, 109,110,111].

As bladderworts are globally widely distributed generalist predators across every continent except Antarctica [55]. All Ae. aegypti- and Ae. albopictus-colonized continents have Utricularia plant species that are suitable for vector-control. The plant here studied, U. macrorhiza, is broadly distributed in North America, Central America and North Asia [55], while Europe and Northern Africa are colonized by a related species also known to predate mosquitoes, U. vulgaris [55, 80]. In Central Africa, Utricularia radiata has recently been identified as a potential biocontrol [54]. To the best of our knowledge, no bladderworts have been examined for their biocontrol properties in South America and Australia, but both continents are considered “hot spots” with regards to Utricularia diversity [112], with various studies documenting the plants’ diets [103, 113], suggesting that finding local alternatives to U. macrorhiza is plausible. The wide distribution of native Utricularia species signifies that this method need not rely on the introduction of non-native species to control mosquitoes in a given area.

Environmental impacts of the use of U. macrorhiza or other Utricularia species should be considered in comparison to the current methods commonly used, both biological and chemical. The proposed application to control Aedes vector species is limited to container-breeding sites rather than natural aquatic systems. The specificity of the bladderworts, predating only aquatic organisms within the container, reduces the impact on non-target organisms. Further, as these are freshwater predators, plant cuttings are not expected to have a negative impact on ecologically beneficial pollinators [114].

Conclusions

This study provides insights into the potential for local predacious bladderworts to work as biological controls of container-breeding mosquitoes, especially in the peri-domestic environment. As an alternative to chemical controls that harm non-target insects, Utricularia produces emergent flowers that are pollinated by insects [115], and thus can supply floral resources for bees. Integrated vector management strategies can reduce impacts on non-target insects, pollinators in particular [114], and any novel method for biocontrol must be evaluated for efficacy in mosquito control as well as its impact on beneficial insects. Future studies should evaluate the feasibility, practicality, and effectiveness of biological control of Aedes larvae using U. macrorhiza and additional Utricularia species under a variety of field conditions. Similarly, interactions between Utricularia plants and other common animal predators utilized for biocontrol should be evaluated to assess interactions that could impact the incorporation of Utricularia into integrated vector management strategies.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets of the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Plants were collected in Rhode Island with permission through a Type I Scientific Collector’s Permit issued by the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management.

References

Yakob L, Funk S, Camacho A, Brady O, Edmunds WJ. Aedes aegypti control through modernized, integrated vector management. PLoS Curr. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1371/currents.outbreaks.45deb8e03a438c4d088afb4fafae8747.

Benelli G, Jeffries CL, Walker T. Biological control of mosquito vectors: past, present, and future. Insects. 2017;7:52.

Shaalan EAS, Canyon DV. Aquatic insect predators and mosquito control. Trop Biomed. 2009;26:223–61.

Carlson J, Keating J, Mbogo CM, Kahindi S, Beier JC. Ecological limitations on aquatic mosquito predator colonization in the urban environment. J Vector Ecol. 2004;29:331.

Kumar R, Hwang JS. Larvicidal efficiency of aquatic predators: a perspective for mosquito biocontrol. Zool Stud. 2006;45:447.

Fletcher M, Teklehaimanot A, Yemane G. Control of mosquito larvae in the port city of Assab by an indigenous larvivorous fish, Aphanius dispar. Acta Trop. 1992;52:155–66.

Homski D, Goren M, Gasith A. Comparative evaluation of the larvivorous fish Gambusia affinis and Aphanius dispar as mosquito control agents. Hydrobiologia. 1994;284:137–46.

Kaneko A, Taleo G, Kalkoa M, Yamar S, Kobayakawa T, Björkman A. Malaria eradication on islands. Lancet. 2000;356:1560–4.

Ghosh SK, Dash AP. Larvivorous fish against malaria vectors: a new outlook. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101:1063–4.

Howard AF, Zhou G, Omlin FX. Malaria mosquito control using edible fish in western Kenya: preliminary findings of a controlled study. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:199.

Chandra G, Bhattacharjee I, Chatterjee SN, Ghosh A. Mosquito control by larvivorous fish. Indian J Med Res. 2008;127:13.

Juliano SA, Philip Lounibos L. Ecology of invasive mosquitoes: effects on resident species and on human health. Ecol Lett. 2005;8:558–74.

Wurtsbaugh WA, Cech JJ. Growth and activity of juvenile mosquitofish: temperature and ration effects. Trans Am Fish Soc. 1983;112:653–60.

Hoddle MS. Restoring balance: using exotic species to control invasive exotic species. Conserv Biol. 2004;18:38–49.

Arthington AH. Ecological and genetic impacts of introduced and translocated freshwater fishes in Australia. Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 1991;48:33–43.

Gamradt SC, Kats LB. The effects of introduced crayfish and mosquito fish on California newts (Taricha torosa). Conserv Biol. 1996;10:1155–62.

Vargas MJ, De Sostoa A. Life history of Gambusia holbrooki (Pisces, Poeciliidae) in the Ebro delta (NE Iberian Peninsula). Hydrobiologia. 1996;341:215–24.

Leyse KE, Lawler SP, Strange T. Effects of an alien fish, Gambusia affinis, on an endemic California fairy shrimp, Linderiella occidentalis: implications for conservation of diversity in fishless waters. Biol Conserv. 2004;118:57–65.

Gophen M, Yehuda Y, Malinkov A, Degani G. Food composition of the fish community in Lake Agmon. Hydrobiologia. 1998;380:49–57.

Wu N, Wang SS, Han GX, Xu RM, Tang GK, Qian C. Control of Aedes aegypti larvae in household water containers by Chinese cat fish. Bull World Health Organ. 1987;65:503–6.

Steffan WA, Evenhuis NL. Biology of Toxorhynchites. Ann Rev Entomol. 1981;26:159–81.

Kraemer MU, Sinka ME, Duda KA, Mylne AQ, Shearer FM, Barker CM, et al. The global distribution of the arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus. Elife. 2015;4:e08347.

Kampen H, Werner D. Out of the bush: the Asian bush mosquito Aedes japonicus japonicus (Theobald, 1901) (Diptera, Culicidae) becomes invasive. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:59.

Trpis M. Development and predatory behavior of Toxorhynchites brevipalpis (Diptera: Culicidae) in relation to temperature. Environ Entomol. 1972;1:537–46.

Lounibos LP. Temporal and spatial distribution, growth and predatory behaviour of Toxorhynchites brevipalpis (Diptera: Culicidae) on the Kenya coast. J Anim Ecol. 1979;48:213–36.

Hubbard SF, O’Malley SLC, Russo R. The functional response of Toxorhynchites rutilus rutilus to changes in the population density of its prey Aedes aegypti. Med Vet Entomol. 1988;2:279–83.

Annis B, Krisnowardojo S, Atmosoedjono S, Supardi P. Suppression of larval Aedes aegypri populations in household water storage containers in Jakarta, Indonesia, through releases of first-instar Toxorhynchites splendens larvae. J Am Mosquito Control Assoc. 1989;5:235–8.

Annis B, Bismo Sarojo UT, Hamzah N, Trenggono B. Laboratory studies laboratory of larval cannibalism in Toxorhynckites amboinensis (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol. 1990;27:777–83.

Corbet PS. Biology of Odonata. Ann Rev Entomol. 1980;25:189–217.

Corbet PS. Dragonflies. Behaviour and ecology of Odonata. Ithaca: Cornell University Press; 1999.

Michiels NK, Dhondt AA. Costs and benefits associated with oviposition site selection in the dragonfly Sympetrum danae (Odonata: Libellulidae). Anim Behav. 1990;40:668–78.

Kalkman VJ, Clausnitzer V, Dijkstra KDB, Orr AG, Paulson DR, van Tol J. Global diversity of dragonflies (Odonata) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia. 2008;595:351–63.

Saha N, Aditya G, Banerjee S, Saha G. Predation potential of odonates on mosquito larvae: implications for biological control. Biol Control. 2012;63:1–8.

Stav G, Blaustein L, Margalit Y. Influence of nymphal Anax imperator (Odonata: Aeshnidae) on oviposition by the mosquito Culiseta longiareolata (Diptera: Culicidae) and community structure in temporary pools. J Vect Ecol. 2000;25:190–202.

Chatterjee SN, Ghosh A, Chandra G. Eco-friendly control of mosquito larvae by Brachytron pratense nymph. J Environ Health. 2007;69:44–9.

Mandal SK, Ghosh A, Bhattacharjee I, Chandra G. Biocontrol efficiency of odonate nymphs against larvae of the mosquito, Culex quinquefasciatus Say, 1823. Acta Trop. 2008;106:109–14.

Sebastian A, Sein MM, Thu MM, Corbet PS. Suppression of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) using augmentative release of dragonfly larvae (Odonata: Libellulidae) with community participation in Yangon, Myanmar. Bul Entomol Res. 1990;80:223–32.

Kay B, Nam VS. New strategy against Aedes aegypti in Vietnam. Lancet. 2005;365:613–7.

Nam VS, Yen NT, Duc HM, Tu TC, Thang VT, Le NH, et al. Community-based control of Aedes aegypti by using Mesocyclops in southern Vietnam. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;86:850–9.

Braks MA, Honório NA, Lourenço-De-Oliveira R, Juliano SA, Lounibos LP. Convergent habitat segregation of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in southeastern Brazil and Florida. J Med Entomol. 2003;40:785–94.

Higa Y, Yen NT, Kawada H, Son TH, Hoa NT, Takagi M. Geographic distribution of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus collected from used tires in Vietnam. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2010;26:1–10.

Locklin JL, Huckabee JS, Gering EJ. A method for rearing large quantities of the damselfly, Ischnura ramburii (Odonata: Coenagrionidae), in the laboratory. Fla Entomol. 2012;95:273–8.

Weterings R, Umponstira C, Buckley HL. Predation rates of mixed instar Odonata naiads feeding on Aedes aegypti and Armigeres moultoni (Diptera: Culicidae) larvae. J Asia Pac Entomol. 2015;18:1–8.

Darwin C, Darwin F. Insectivorous plants. London: John Murray; 1875.

Matheson R. The utilization of aquatic plants as aids in mosquito control. Am Nat. 1930;64:56–86.

Twinn CR. Observations on some aquatic animal and plant enemies of mosquitoes. Can Entomol. 1931;63:51–61.

Bukhari T, Takken W, Koenraadt CJ. Biological tools for control of larval stages of malaria vectors—a review. Biocontrol Sci Tecn. 2013;23:987–1023.

Ong SQ. Dengue vector control in Malaysia: a review for current and alternative strategies. Sains Malays. 2016;45:777–85.

Taylor P. The genus Utricularia. A taxonomic monograph. Kew Bull. 1989;79:613–22.

Baumgartner DL. Laboratory evaluation of the bladderwort plant, Utricularia vulgaris (Lentibulariaceae), as a predator of late instar Culex pipiens and assessment of its biocontrol potential. J Am Mosquito Control Assoc. 1987;3:504–7.

Gordon E, Pacheco S. Prey composition in the carnivorous plants Utricularia inflata and U. gibba (Lentibulariaceae) from Paria Peninsula. Venez Rev Biol Trop. 2007;55:795–803.

Alkhalaf IA, Hübener T, Porembski S. Prey spectra of aquatic Utricularia species (Lentibulariaceae) in northeastern Germany: the role of planktonic algae. Flora. 2009;204:700–8.

Evans AM, Garnham PCC. The funestus series of Anopheles at Kisumu and a coastal locality in Kenya. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1936;30:511–20.

Ogwal-Okeng J, Namaganda M, Bbosa GS, Kaleman J. Using carnivorous plants to control malaria-transmitting mosquitoes. MalariaWorld J. 2013;4:1–3.

Silva SR, Gibson R, Adamec L, Domínguez Y, Miranda VF. Molecular phylogeny of bladderworts: a wide approach of Utricularia (Lentibulariaceae) species relationships based on six plastidial and nuclear DNA sequences. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2018;118:244–64.

Hawley WA. The biology of Aedes albopictus. J Am Mosquito Control Assoc. 1988;1:1–39.

Livdahl TP, Willey MS. Prospects for an invasion: competition between Aedes albopictus and native Aedes triseriatus. Science. 1991;253:189–91.

Benedict MQ, Levine RS, Hawley WA, Lounibos LP. Spread of the tiger: global risk of invasion by the mosquito Aedes albopictus. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2007;7:76–85.

Kraemer MUG, Reiner RC, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Gilbert M, Pigott DM, et al. Past and future spread of the arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4:854–63.

Montarsi F, Martini S, Michelutti A, Da Rold G, Mazzucato M, Qualizza D, et al. The invasive mosquito Aedes japonicus japonicus is spreading in northeastern Italy. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12:120.

Akiner MM, Demirci B, Babuadze G, Robert V, Schaffner F. Spread of the invasive mosquitoes Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in the Black Sea region increases risk of chikungunya, dengue, and Zika outbreaks in Europe. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004664.

Chouin-Carneiro T, Vega-Rua A, Vazeille M, Yebakima A, Girod R, Goindin D, et al. Differential susceptibilities of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus from the Americas to Zika virus. PLoS Neg Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004543.

Powell JR. Mosquitoes on the move. Science. 2016;354:971–2.

Mazid S, Kalita JC, Rajkhowa RC. A review on the use of biopesticides in insect pest management. Int J Sci Adv Technol. 2011;1:169–78.

Kasai S, Caputo B, Tsunoda T, Cuong TC, Maekawa Y, Lam-Phua SG, et al. First detection of a Vssc allele V1016G conferring a high level of insecticide resistance in Aedes albopictus collected from Europe (Italy) and Asia (Vietnam), 2016: a new emerging threat to controlling arboviral diseases. Euro Surveill. 2019;24:1700847.

Grier JW. Ban of DDT and subsequent recovery of reproduction in bald eagles. Science. 1982;218:1232–5.

Koureas M, Tsakalof A, Tsatsakis A, Hadjichristodoulou C. Systematic review of biomonitoring studies to determine the association between exposure to organophosphorus and pyrethroid insecticides and human health outcomes. Toxicol Lett. 2012;210:155–68.

Jakob C, Poulin B. Indirect effects of mosquito control using Bti on dragonflies and damselflies (Odonata) in the Camargue. Insect Conserv Divers. 2016;9:161–9.

Agnew P, Haussy C, Michalakis Y. Effects of density and larval competition on selected life history traits of Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol. 2000;37:732–5.

Richards JH. Bladder function in Utricularia purpurea (Lentibulariaceae): is carnivory important? Am J Bot. 2001;88:170–6.

Manjarrés-Hernández A, Guisande C, Torres NN, Valoyes-Valois V, González-Bermúdez A, Díaz-Olarte J, et al. Temporal and spatial change of the investment in carnivory of the tropical Utricularia foliosa. Aquat Bot. 2006;85:212–8.

Adamec L. By which mechanism does prey capture enhance plant growth in aquatic carnivorous plants: stimulation of shoot apex? Fundam Appl Limnol. 2011;178:171–6.

Ellwood NT, Congestri R, Ceschin S. The role of phytoplankton in the diet of the bladderwort Utricularia australis R.Br. (Lentibulariaceae). Freshwat Biol. 2019;64:233–43.

RStudio Team. RStudio: integrated development for R. Boston: RStudio, Inc; 2016.

Therneau TM. A package for survival analysis in S. v.2.42. 2015. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival.

Thermeau TM, Grambsch PM. Modeling survival data: extending the Cox model. New York: Springer Verlag; 2000.

Grambsch P, Therneau T. Proportional hazards test and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81:515–26.

Harrington DP, Fleming TR. A class of rank test procedures for censored survival data. Biometrika. 1982;69:533–66.

Karadeniz PG, Ercan I. Examining tests for comparing survival curves with right censored data. Stat Transit. 2017;18:311–28.

Gordeev MI, Sibataev AK. Influence of predatory plant bladderwort (Utricularia vulgaris) on the process of selection in malaria mosquito larvae. Russ J Ecol. 1995;26:216–20.

Friday LE. The size and shape of traps of Utricularia vulgaris L. Funct Ecol. 1991;5:602–7.

Knight SE, Frost TM. Bladder control in Utricularia macrorhiza: lake-specific variation in plant investment in carnivory. Ecology. 1991;72:728–34.

Knight SE. Costs of carnivory in the common bladderwort, Utricularia macrorhiza. Oecologia. 1992;89:348–55.

Guiral D, Rougier C. Trap size and prey selection of two coexisting bladderwort (Utricularia) species in a pristine tropical pond (French Guiana) at different trophic levels. Int J Limnol. 2007;43:147–59.

Guisande C, Andrade C, Granado-Lorencio C, Duque SR, Núñez-Avellaneda M. Effects of zooplankton and conductivity on tropical Utricularia foliosa investment in carnivory. Aquat Ecol. 2000;34:137–42.

Angerilli NP, Beirne BP. Influences of some freshwater plants on the development and survival of mosquito larvae in British Columbia. Can J Zool. 1974;52:813–5.

Friday LE. Rapid turnover of traps in Utricularia vulgaris L. Oecologia. 1989;80:272–7.

Englund G, Harms S. Effects of light and microcrustacean prey on growth and investment in carnivory in Utricularia vulgaris. Freshwat Biol. 2003;48:786–94.

Adamec L. Respiration and photosynthesis of bladders and leaves of aquatic Utricularia species. Plant Biol. 2006;8:765–9.

Adamec L. Mineral nutrient relations in the aquatic carnivorous plant Utricularia australis and its investment in carnivory. Fundam Appl Limnol. 2008;171:175–83.

Hanson WR. Effects of some herbicides and insecticides on biota of North Dakota marshes. J Wildl Manage. 1952;16:299–308.

Smith CS, Pullman GD. Experiences using Sonar® AS aquatic herbicide in Michigan. Lake Reserv Manag. 1997;13:338–46.

Brewer JS. Effects of competition, litter, and disturbance on an annual carnivorous plant (Utricularia juncea). Plant Ecol. 1999;140:159–65.

Collins LE, Blackwell A. The biology of Toxorhynchites mosquitoes and their potential as biocontrol agents. Biocontr News Inform. 2000;21:105–16.

Lacey LA, Merritt RW. The safety of bacterial microbial agents used for black fly and mosquito control in aquatic environments. In: Hokkanen HMT, Hajek AE, editors. Environmental impacts of microbial insecticides: need and methods for risk assessment. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2003. p. 151–68.

Sawchyn WW, Gillott C. The biology of two related species of coenagrionid dragonflies (Odonata: Zygoptera) in western Canada. Can Entomol. 1975;107:119–28.

Angerilli NP, Beirne BP. Influences of aquatic plants on colonization of artificial ponds by mosquitoes and their insect predators. Can Entomol. 1980;112:793–6.

Lenz N. The importance of abiotic and biotic factors for the structure of odonate communities of ponds (Insecta: Odonata). Faun Okol Mitt. 1991;6:175–89.

Fincke OM, Yanoviak SP, Hanschu RD. Predation by odonates depresses mosquito abundance in water-filled tree holes in Panama. Oecologia. 1997;112:244–53.

Fincke OM. Organization of predator assemblages in Neotropical tree holes: effects of abiotic factors and priority. Ecol Entomol. 1999;24:13–23.

Yanoviak SP. Container color and location affect macroinvertebrate community structure in artificial treeholes in Panama. Fla Entomol. 2001;84:265–71.

Yanoviak SP. Predation, resource availability, and community structure in Neotropical water-filled tree holes. Oecologia. 2001;126:125–33.

Walker I. Trophic interactions within the Utricularia habitat in the reservoir of the Balbina hydroelectric powerplant (Amazonas, Brazil). Acta Limn Brasil. 2004;16:183–91.

Faithpraise FO, Idung J, Usibe B, Chatwin CR, Young R, Birch P. Natural control of the mosquito population via Odonata and Toxorhynchites. Int J Innov Res Sci Eng Technol. 2014;3:12898–911.

Morrison AC, Zielinski-Gutierrez E, Scott TW, Rosenberg R. Defining challenges and proposing solutions for control of the virus vector Aedes aegypti. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e68.

Harms S. The effect of bladderwort (Utricularia) predation on microcrustacean prey. Freshwat Biol. 2002;47:1608–17.

Friday LE. Measuring investment in carnivory: seasonal and individual variation in trap number and biomass in Utricularia vulgaris L. New Phytol. 1992;121:439–45.

Andreadis TG, Thomas MC, Shepard JJ. Identification guide to the mosquitoes of Connecticut (No. 966). New Heaven: The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station; 2005.

Miyagi I, Toma T, Mogi M. Biological control of container-breeding mosquitoes, Aedes albopictus and Culex quinquefasciatus, in a Japanese island by release of Toxorhynchites splendens adults. Med Vet Entomol. 1992;6:290–300.

Focks DA. Toxorhynchites as biocontrol agents. J Am Mosquito Control Assoc. 2007;23(Suppl. 2):118–28.

Anderson JF, Ferrandino FJ, Dingman DW, Main AJ, Andreadis TG, Becnel JJ. Control of mosquitoes in catch basins in Connecticut with Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis, Bacillus sphaericus, and spinosad. J Am Mosquito Control Assoc. 2011;27:45–56.

Poppinga S, Weisskopf C, Westermeier AS, Masselter T, Speck T. Fastest predators in the plant kingdom: functional morphology and biomechanics of suction traps found in the largest genus of carnivorous plants. AoB Plants. 2016;8:pvl140.

Płachno BJ, Łukaszek M, Wołowski K, Adamec L, Stolarczyk P. Aging of Utricularia traps and variability of microorganisms associated with that microhabitat. Aquat Bot. 2012;97:44–8.

Ginsberg HS, Bargar TA, Hladik ML, Lubelczyk C. Management of arthropod pathogen vectors in North America: minimizing adverse effects on pollinators. J Med Entomol. 2017;54:1463–75.

Proctor M, Yeo P. The pollination of flowers. London: Collins; 1973.

Acknowledgements

The following reagents were obtained through the NIH Biodefense and Emerging Infections Research Resources Repository, NIAID, NIH, MR4 program: Aedes aegypti, Strain Orlando orco2, NR-44376, and Aedes albopictus, Strain ATM-NJ95, eggs, NR-48979. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the USA Government.

Funding

This research was supported by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Hatch Regional project 1021058.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JC and NLC conceived the project. NLC identified plant species from field collections. JC and MN collected plant materials, set up experiments, and collected data, analyzed and interpreted data, and were major contributors to the writing of the manuscript. SV collected plant materials and conducted critical preliminary pilot studies to inform the experimental design. NLC, HG and RL provided manuscript revisions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Video S1.

Third-instar Ae. aegypti larva captured by an Utricularia macrorhiza bladder under artificial container conditions.

Additional file 2: Video S2.

Fourth-instar Ae. aegypti larva captured by an Utricularia macrorhiza bladder under artificial container conditions.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Couret, J., Notarangelo, M., Veera, S. et al. Biological control of Aedes mosquito larvae with carnivorous aquatic plant, Utricularia macrorhiza. Parasites Vectors 13, 208 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04084-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04084-4