Abstract

Background

Trypanosoma cruzi is a protozoan parasite characterized by extensive genetic heterogeneity. There are currently six recognised, genetically distinct, monophyletic clades designated discrete typing units (DTUs). TcI has the broadest geographical range and most genetic diversity evidenced by a wide range of genetic markers applied to isolates spanning a vast geographical range across Latin America. However, little is known of the diversity of TcI that exists within sylvatic mammals across the geographical expanse of Brazil.

Results

Twenty-nine sylvatic TcI isolates spanning multiple ecologically diverse biomes across Brazil were analyzed by the application of multilocus sequence typing (MLST) using four nuclear housekeeping genes. Results revealed extensive genetic diversity and also incongruence among individual gene trees. There was no association of intralineage genotype with geography or with any particular biome, with the exception of isolates from Caatinga that formed a single cluster. However, haplotypic analyses of METIII and LYT1 constitutive markers provided evidence of recombination events in two isolates derived from Didelphis marsupialis and D. albiventris, respectively. For diversity studies all possible combinations of markers were assessed with the objective of selecting the combination of gene targets that are most resolutive using the minimum number of genes. A panel of just three gene fragments (DHFR-TS, LYT1 and METIII) discriminated 26 out of 35 genotypes.

Conclusions

These findings showed geographical association of genotypes clustering in Caatinga but more characteristically TcI genotypes widely distributed without specific association to geographical areas or biomes. Importantly, we detected the signature of recombination events at the nuclear level evidenced by haplotypic analysis and incongruence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, the causative agent of Chagas disease, is a vector-borne zoonosis transmitted by hematophagous triatomine bugs (Hemiptera: Reduviidae: Triatominae). They are maintained in the sylvatic environment by a wide range of mammalian hosts species and endemic from southern USA to southern Argentina [1, 2]. The primary route of infection in humans is contact with infected triatomine bug faeces that are deposited on the skin during the blood meal. Infection occurs when parasites enter mammal hosts through skin lesions, the insect bite wound or directly through the mucosa. Domiciliated infestation of triatomine bugs has not been reported from the Amazon basin but enzootic transmission from non-domiciliated adult triatomines is known to occur [3]. Moreover sporadic human infection by T. cruzi is re-emerging as a food-borne disease in areas that were not previously endemic for Chagas disease. In the Amazon, oral infection is associated primarily with the ingestion of infected açaí juice and bacaba juice [4,5,6]. Also, in Venezuela, an outbreak of over 100 cases of acute Chagas disease was caused by the ingestion of fresh guava juice in one school in Cacaras [7] due to poor hygiene measures in the preparation of the fruit juice.

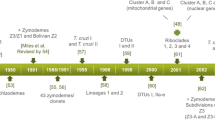

A salient feature of T. cruzi is extensive genetic heterogeneity [8,9,10,11]. The species is currently subdivided into six genetically discrete typing units (DTUs), TcI to TcVI [12, 13], and an additional clade associated with bats (TcBat) has been proposed [14]. TcI and TcII are ancient lineages that diverged from a common ancestor approximately 1–3 million years ago [10]. TcV and TcVI clearly have a relatively recent hybrid origin derived from TcII and TcIII [15]. According to some authors, TcIII and TcIV also originated from a more ancient hybridization of TcI and TcII [16, 17], although others claim that it is not the case [10, 18].

TcI is widespread from the southern USA to northern Argentina and Chile and infects many different mammal host including humans, domestic and sylvatic species, transmitted by triatomine bug vectors. TcI is the most frequently sampled DTU in wild transmission cycles, although it was also observed in domestic cycles [19, 20] and is the dominant DTU in terms of Chagas disease transmission in endemic regions north of the Amazon Basin [21]. In Brazil, TcI represents 58% of recovered sylvatic T. cruzi isolates [8]. Moreover, in Brazil, the distribution of DTUs does not appear to have an association with particular biomes or geographical areas [8]. Some species including bats and, in particular, marsupials (Didelphis spp.) are considered to be ancient reservoir hosts of T. cruzi [22]. Didelphids are nomadic sylvatic/synanthropic species and widely distributed throughout Brazil’s biomes, inhabiting both terrestrial and arboreal niches [8]. They are omnivorous and highly adaptable, capable of colonizing environments degraded by humans and are classically associated with the T. cruzi I genotype [23]. However, they are also able to harbor other T. cruzi DTUs. Hence, Didelphis spp. are exposed to T. cruzi infection across different transmission cycles and act as bioaccumulators of TcI intralineage genotypes [8].

The genetic diversity present in TcI has been assessed by a plethora of molecular methods including random amplification of polymorphic DNA (RAPD), multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (MLEE), internal transcribed spacer (ITS), and polymorphisms in minicircles and in the miniexon gene [23,24,25,26,27,28]. Several studies based on the microsatellite motif of spliced ladder intergenic regions (SL-IR) indicate the existence of five groups within TcI (Ia-Ie) and potential associations to anthropogenic or wild environments [16, 28,29,30,31,32]. However, a review of the SL-IR classification of five subgroups of TcI showed that there was no conclusive evidence of genetic structuring between domestic and wild isolates, but rather an association with geographical distribution [33, 34]. Ramirez et al. [35], using nuclear gene targets and MLST, demonstrated the existence of two TcI groups in Colombian isolates: one associated with the wild transmission cycle (TcI SILV) and the other with domestic transmission (TcI DOM). The latter has previously been classified as TcIa and TcI VENDom [28, 36]. Ramirez & Hernandez [37] provided evidence for a possible subdivision of TcI (into DOM and SILV), although they also stated that the substancial diversity present in TcI did not allow conclusive identification of TcIDom as a robust near-clade.

MLST involves the sequencing of constitutive gene fragments. Initially applied to bacteria and yeast, and subsequently adapted and applied to diploid organisms, including Trypanosoma cruzi [38, 39] and Leishmania spp. [40]. The major advantage of MLST analysis is that sequence data are unequivocal with sufficient resolution for epidemiological diversity and population studies [38]. Furthermore, results are objective and easily accessible for some pathogens via online database repositories such as MLST.net [38]. Previously, and specific to T cruzi, Yeo et al. [38] applied MLST analysis using nine constitutive genes to evaluate the diversity across different DTU’s. Additionally, Lauthier et al. [39] assessed diversity on T. cruzi, using ten markers. Moreover, Messenger et al. [41] developed an MLST maxicircle typing scheme using ten gene targets applied to TcI isolates from disparate locations revealing extensive mitochondrial introgression and heteroplasmy. Furthermore, to analyze the variability of TcI in Colombia, Ramirez et al. [35], applied MLST analysis to 13 constitutive genes.

Brazil is a vast country, containing an enormous diversity of habitats and high biodiversity. Yet, little is known of the intra-DTU diversity of TcI in mammals, and more specifically in Didelphis spp., in Brazil. We investigate the potential for TcI subpopulation associations in the context of species of the marsupial genus Didelphis and their role in transmission cycles and as bioaccumulators of T. cruzi. We apply MLST analysis of four housekeeping genes, to assess the genetic heterogeneity of TcI isolates obtained from Didelphis spp. that were captured in four different Brazilian biomes spanning a vast geographical range.

Methods

Parasite isolates

A total of twenty nine TcI isolates, available in the Coleção de Trypanosomas de mamiferos silvestres, domesticos e vetores (ColTryp) at the Laboratório de Biologia de Tripanosomatídeos do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz/FIOCRUZ, were sampled from Didelphis marsupialis, D. albiventris and D. aurita, captured in four Brazilian biomes: Atlantic Forest, Amazon, Caatinga and Cerrado (Fig. 1 and Table 1). TcI isolates that had previously been confirmed as TcI using Mini-Exon polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [42] by ColTryp, were genotyped by MLST with appropriate reference sequences.

Details of the origin and geographical distribution of the isolates are given in Table 1 and Fig. 1, respectively.

MLST: Choice of loci

Four nuclear TcI gene fragments were selected for MLST analysis. The choice of targets was based on a previous work conducted by Yeo et al. [38] that showed the intralineage discriminatory capacity of 9 nuclear genes applied to T. cruzi. The four genes selected were: DHFR-TS (dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase); RB19 (RNA-binding protein-19), METIII (metacyclin-III), and LYT1 (lytic pathway protein).

Molecular methods

PCRs were performed using different reaction conditions following Yeo et al. [38] with some modifications. For DHFR-TS, initial denaturation was at 94 °C for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 1 min and 72 °C for 2 min. The cycle conditions for amplification of RB19, METIII and LYT1 genes were: 94 °C for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, with an annealing temperature of 53 °C (RB19), 51 °C (METIII) or 57 °C (LYT1) for 30 s, and an extension of 72 °C for 45 s. All reactions had a final additional extension of 72 °C for 10 min. Each 25 μl total reaction volume contained: 50 ng genomic DNA, 0.2 μM of each primer, 2 mM of each dNTPs, 50 mM MgCl2 solution and 1 U Taq (BIO-21086, Bioline, London, UK). The products were visualized on agarose (2%) stained with ethidium bromide. PCR products were purified using Illustra GFX PCR DNA and Gel Band Purification Kits (GE Healthcare, Little, Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK). Bi-directional sequencing was performed using PCR primers and Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing v.3.1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster city, CA, USA) in an ABI PRISM 3730 DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems) using standard protocols. Bio Edit v.7.0.4.1 [43] and DNASTAR Lasergene SeqMan v.7.0.0 programs were used to align and edit DNA sequences. Heterozygous positions were identified manually by the presence of two coincident peaks at the same locus (“split peaks”), verified in both forward and reverse directions and scored according to one-letter International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) nomenclature. All edited sequences were deposited in the GenBank database under the accession numbers MG228275–MG228358 and MG868953–MG868980 (Table 1).

Data analyses for MLST

Gene sequences were analyzed to investigate intralineage diversity, evidence of recombination via phylogenetic incongruence at the level of individual diplotypes and haplotypes, and also to determine the best combination and minimum combination of loci that enable identification of the maximum number of diploid sequence types (DSTs). MLSTest software [44] was initially applied to calculate the typing efficiencies (TE) and discriminatory power (DP) for each target. TE is defined as the number of identified genotypes divided by the number of polymorphic sites within the target locus [45]. DP is defined as the probability that two strains are distinguishable when chosen at random from a population of unrelated strains [39].

Trypanosoma cruzi is a minimally diploid organism and as such heterozygosity renders MLST analysis more difficult than in haploid organisms. As mentioned above, heterozygosity was inferred from electropherograms by a double peak (two bases) at the same variable bi-allelic site [46]. One consequence of multiple bi-allelic sites is the presence of ambiguous allelic phases within loci and also ambiguous combinations of alleles across separate loci. However, it is possible for diploid sequence data (without phase resolution) to be concatenated across multiple loci [38, 45] and subsequently subjected to distance-based phylogenetic methods for the study of lineage assignment and of recombination. Here we apply an average state methodology described by Diosque et al. [45]. In more detail, the genetic distance between T and Y (heterozygosity composed of T and C) is considered as the mean distance between the T and the possible resolutions of Y (distance T-T = 0 and distance T-C = 1, average distance = 0.5, see Diosque et al. [45] and MLSTest software [44] for further details.

Incongruence between phylogenetic trees derived from individual gene targets was analyzed via incongruence length difference (ILD) tests, in MLSTest software [44]. ILD tests evaluate differences between expected and observed incongruences between loci in the context of random unstructured homoplasy. All combinations from 2 to 4 fragments were analyzed using the optimization algorithm scheme in MLSTest which identifies the minimum combination of loci producing the maximum number of DSTs.

Phylogenetic analyses, for individual and concatenated genes sequences were performed using neighbor-joining (NJ) trees, implemented in MLSTest v.1.0 [44]. NJ trees were constructed using uncorrected p-distances, considering heterozygous sites as average states. One thousand bootstrap replications were used to evaluate branch support.

To infer haplotypes for each gene, diploid sequence data were analized using PHASE software v.2.1 [47]. This program is based on a modified Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm which identified and assembles all unambiguous haplotypes. Bayesian phylogenetic analysis was subsequently performed (MrBayes), implemented through TOPALi v.2.5 [48], using the best-fit model selected, Hasegawa-Kishino-Yano plus gamma distributed rate variation among sites (HKY + G), based on the Bayesian information criterion. Five MCMC runs were carried out in parallel for one million generations with sampling every 100 generations and 25% burn in.

Reference sequences were obtained from LSHTM collaborators, from Yeo et al. [38] comprising TcI [C8 cl1, SAXP18 cl1, 9210601P cl1, PI (CJ007), PII (CJ005)] and also Tu18cl2 (TcII) and GenBank sequence (X10/1, CP015651.1). In addition to phylogenetic incongruence between single gene trees, analysis of allelic recombination to detect allelic gene mosaics at the level of individual genes was undertaken. Isolates with unambiguous phases were applied through the software package RDP3 (recombination detection program) [49], incorporating the following methods: RDP [50], Bootscanning [51], GENECONV [52], Maximum Chi Square method [53, 54], the Chimaera method [53], the Sister Scanning Method [55], the 3SEQ method [56].

Results

Genetic diversity and discriminatory power of MLST by diploid sequence typing

We observed a significant genetic diversity in the context of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), as well as differences and variations in discriminatory powers (DP) of the four constitutive gene fragments under study (Table 2).

For individual genes, the number of polymorphic sites ranged from 4 (DHFR-TS) to 14 (LYT1) and the associated number of alleles ranged from 4 (DHFR-TS) to 14 (LYT1 and RB19). The most resolutive marker, i.e. distinguishing most genotypes, was RB19 (TE = 2), which also possessed the highest discriminatory power (DP = 0.92). LYT1 and DHFR-TS were the least resolutive genes (TE = 1), with DHFR-TS also possessing the lowest DP value of 0.31. The DP of 4 concatenated targets by MLST was 0.993, discriminating 33 out 35 isolates.

Single locus phylogenies and MLST

Phylogenetic trees were generated for each marker (Additional file 1: Figure S1 and Additional file 2: Figure S2) to assess diversity and incongruence in topology. In more detail, DHFR-TS isolates formed a single cluster, indicative of limited variation, a finding in agreement with TE and DP figures for this target. All isolates grouped with reference sequences, with the exception of one isolate (8622) from Caatinga (Additional file 1: Figure S1). RB19 revealed the presence of several clusters, although with relative low bootstrap support. Two clusters displayed bootstrap support > 50%: one containing 3 isolates from the Cerrado biome (9425, 8552, 9149), and the other cluster including 3 isolates from Amazonia (12667, 10272, 12625), one from the Atlantic Forest (G41) and 2 reference sequences (B187, X10). LYT1 produced a single cluster containing all 10 isolates from Caatinga (bootstrap value = 61%) (Additional file 2: Figure S2). Here again, 8552 and 9149 samples from Cerrado grouped together (bootstrap value = 64%). Within LYT1, reference sequences X10 (Bolivian T. infestans), C8 (Bolivian T. infestans) and SAXP18 (Peruvian Didelphis marsupials) clustered with moderate and high support (bootstrap values of 87 and 98%, respectively). The METIII tree (Additional file 1: Figure S1) supported a single cluster (bootstrap support > 58%) and grouped the sample 12668 from the Amazon region and 6812 from Caatinga with the reference sequences 9210160 (Didelphis marsupials, US) and X10, respectively.

Trees generated with LYT1 and RB19 (Additional file 2: Figure S2) and METIII (Additional file 1: Figure S1) genes, also exhibited topological inconsistencies. For example, within LYT1 the subgroup containing all isolates from the Caatinga biome was not observed in other trees. The Atlantic Forest isolate G41 was similarly positioned in both LYT1 and METIII topologies within Amazonian, Cerrado and Atlantic Forest isolates. In contrast, G41 was positioned in a well-defined cluster for RB19 which contained isolates solely from the Amazon region (bootstrap value of 53%) (Additional file 2: Figure S2).

Intra DTU I diversity

The resolutive power for all four genes was assessed by concatenation to produce a single phylogeny. Generally, clusters consisted of a mixture of isolates from geographically disparate regions with the exception of the isolates originating from the Caatinga biome. In more detail, five clusters with moderate bootstrap support were observed (Fig. 2).

Neighbor-joining tree based on the concatenation of 4 MLST fragments. NJ trees were constructed using uncorrected p-distances and considering heterozygous sites as average states. Branch values represent bootstrap values (1000 replications). Circles with colors represent the municipalities in each biome where samples were obtained: Amazon (red); Caatinga (green); Atlantic Forest (yellow); Cerrado (blue)

Cluster a (bootstrap value of 56%) exclusively included isolates from the Caatinga biome, as observed previously with LYT1. Cluster b (bootstrap value of 62%) included isolates from very distant regions, including the Atlantic Forest (G41 - Rio de Janeiro) and Amazonia (12667 - Curralinho), indicating the wide distribution of this TcI genotype. Cluster c (bootstrap value of 51%) grouped Atlantic Forest isolates (Rio de Janeiro) and a single isolate from Cerrado (Goias) further evidencing the wide distribution of the TcI genotypes (Fig. 1). Cluster d (bootstrap value of 60%) (Fig. 2) was comprised of remaining isolates from the Cerrado biome. Lastly, cluster e (bootstrap value of 57%) included the reference sequences X10, C8 and SAXP, as previously observed in the LYT1 phylogeny.

Applying measures of incongruence across all combinations reveal the four fragment datasets are significantly incongruent (P < 0.05). However, on excluding RB19 the P-value for ILD was not significant (BIONJ-ILD = 0.4) indicating that DHFR-TS, LYT1 and MET III are broadly congruent (Fig. 3).

Intralineage recombination

To further assess evidence for recombination, the allelic origins for each target were investigated. Haplotypes and associated phylogenies were generated for each of the three gene fragments (LYT1, METIII and RB19). Based on these haplotypes we observed evidence of genetic recombination among isolates in two genetic targets.

The haplotypic trees for METIII revealed the putative homozygous donors genotypes, situated in different clusters and their corresponding heterozygous profiles (Fig. 4). Specifically, heterozygous isolate 12640 contained alleles that are consistent with putative donor haplotypes from homozygous isolates 12625 and 12668. Putative donor homozygous SNP profiles and the corresponding heterozygous profiles are presented in the Additional file 3: Table S1.

Secondly LYT1 demonstrated heterozygous haplotypes for isolate 9149 and D7, which clustered with its putative homozygous donors 8552 and 9425, and 6737 and 6716, respectively (Fig. 5). Putative donor-homozygous SNP profiles and the corresponding heterozygous profiles are presented in the Additional file 4: Table S2. Although this gives evidence of recombination at the level of allelic inheritance, for example through the segregation of alleles, we did not observe evidence of allelic recombination (mosaic alleles) through the RDP approach.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the genetic diversity present in Brazilian TcI isolates, obtained from Didelphis spp. using an MLST approach. Our results confirmed the existence of significant genetic diversity within TcI in Brazilian didelphids [29, 32, 36]. Although we observed some evidence of geographical association in the Caatinga biome forming a single cluster (LYT1 target) there was a general lack of population structure in association to any particular biome or habitat. Moreover, isolates originated from Didelphis spp. from geographically disparate areas and biomes possessed identical or similar genotypes.

MLST applied to 35 sequences (including reference sequences) indicated that the concatenation of the four gene fragments was highly discriminatory, identifying 33 out of 35 possible DSTs; however, a reduced panel of markers that included DHFR-TS, METIII and LYT1 can discriminate 26 of 35 DSTs (Fig. 3). LYT1 was the most polymorphic of the four fragments analyzed, in agreement with Ramirez et al. [36] and Yeo et al. [38]. However, a caveat to routine use of this target is the difficulty in optimizing reaction conditions to produce consistent quality sequence data, also observed by Yeo et al. [38].

RB19, with 7 polymorphic sites, possessed the highest typing efficiency (TE = 2), indicating that it is an excellent candidate for TcI diversity studies. Conversely, DHFR-TS was the least polymorphic. Yeo et al. [38] applied this marker for intralineage diversity studies finding it useful for discriminating DTUs TcVI and TcV. Despite the low number of SNPs we observed that the DP increased (0.25–0.31) with the inclusion of the DHFR-TS. However, in the context of a TcI specific cohort we suggest alternative, more discriminatory markers to DHFR-TS, be considered.

We also observed incongruences between phylogenetic trees, constructed with individual gene fragments, one explanation for which would be genetic recombination. Our data showed that isolates appeared in different clusters in the individual trees (Additional file 1: Figure S1 and Additional file 2: Figure S2). The existence of incongruences between constitutive gene trees has previously been observed in different lineages [19, 40, 45, 57] and it is considered a marker of populations that have undergone genetic recombination. The evidence for recombination is further supported by haplotypic phylogenies that infer allelic inheritance from homozygous donor genotypes. Importantly, for MET III and LYT1, heterozygous isolates were observed with their corresponding homozygous SNP donor genotypes (Additional file 3: Table S1 and Additional file 4: Table S2). We also examined haplotype sequences using various recombination detection algorithms (through RDP3), applied to individual alleles; we found no evidence of mosaics. As already observed by Yeo et al. [38], this result is not unexpected as the allelic recombination (mosaics) may be a rare event in comparison to inheritance by segregation of allelic haplotypes from and homozygous parental donors [38, 46]. TcV and TcVI, known recombinants of TcII and TcIII, were originally characterized by SNP distribution, in this way. Recombination in Tcl has been proven experimentally in a landmark publication [58], and in natural populations [20, 35, 41]. The frequency of recombination is unknown and may be common [41, 59] or rare [60, 61]. To obtain more refined results in the future, it would be important to include a much larger cohort of isolates with further cloning for downstream recombination analysis.

Concatenation of the four genes resulted in clustering all Caatinga isolates and excluded isolates from the other biomes, suggesting a geographical association at some level. It is worth noting that the area in question is rather extended, e.g. the municipalities of Jaguaruana and Sao Reimundo Nonato are separated by a distance of nearly 900 km (much more than the typical hosts displacement) and numerous barriers to hosts movement, including cities and roads [62]. The presence of similar genotypes over a wide area is in agreement with previous studies [63].

We generally observed similar genotypes spanning vast geographical distances, which is likely indicative of host/vector dispersion or clonal propagation over time against a background of intermittent recombination. As a further case in point, genetically similar genotypes were also present in both Atlantic Forest and Amazonia (cluster b, Fig. 2) forming a discrete subcluster, despite the corresponding localities being separated by a huge geographical distance. Amazonian isolates 12625 (Abaetetuba) and 10272 (Cachoeira do Arari) were clustered together despite their localities being separated by Bahia de Marajo, providing further evidence that similar genotypes span substantial distances across geographical barriers (Fig. 2). From our data, it is clear that different genotypes circulate sympatrically and infect multiple Didelphis spp. Of note, some of the localities, such as Abaetetuba and Curralinho in the state of Para, correspond to outbreak areas of Chagas disease [64]. Noticeably, Abaetetuba (Amazonian 12640, 12625) has had several outbreaks of Chagas disease reported [65]. Moreover, Llewellyn et al. [36] and also Ramirez et al. [35] identified specific genotypes involved in domestic and sylvatic transmission cycles in Venezuela (by microsatellites) and Colombia (by MLST), respectively. However, to investigate this possibility in Brazil a larger cohort of isolates originated from vectors, mammals, sylvatic and domestic isolates would be required.

We also observed local genotypic diversity as all isolates from the Cerrado biome (n = 4) were obtained from the same municipality (Apore), yet, only three of them grouped in the same cluster indicating localized diversity (Fig. 2). This phenomenon was observed by Lima et al. [63] who also detected extensive genetic diversity, in mainly sylvatic hosts, by the application of microsatellite analysis to isolates from the Cerrado biome (Tocantins), in which case these isolates clustered with isolates from the Atlantic Forest. Hence, the recurring theme from TcI in didelphids, presented here and also from also other TcI studies in Brazil, is one of extensive diversity but also with genetically similar isolates being present in disparate regions.

The presence of multiclonality in single hosts is known to occur [60, 66] and is a potential confounder for the genetic analysis from DNA from uncloned isolates. However, evidence from this particular cohort suggests that multiclonality can be ruled out as an explanation of the observed results. Specifically, as stated above, RDP analysis testing for recombination at the level of alleles (intra-allelic recombination) did not detect allelic mosaics in the clonal controls or the field isolates, which would likely be observed in the presence of mixed clones in individual isolates. Moreover, the evidence for recombination is derived from discrete allelic contributions from potential donor homozygous genotypes (and not allelic mosaics), further supporting the case for genetically discrete isolates over that of admixtures. Finally, these data show that similar genotypes span huge geographical distances. This is also suggestive of genetically discrete isolates and not admixtures of different clones. Together these results provide robust evidence for genetic diversity between discrete isolates within TcI.

The main epidemiological implication of our findings, is that there is no observed association between the distribution of subpopulations of TcI and the appearance of outbreaks of CD. Moreover, in Brazil, TcI has been classically associated with the sylvatic transmission cycle. This is, in part, due to its high prevalence in mammals and its high dispersion [42]. However, TcI has also been detected in human cases [67], in which it originated from sylvatic mammals including Didelphis spp. These marsupials are found in all forest strata in all biomes of Brazil. Additionally, they are known to dwell habitats in the proximity of human activity. These facts, together with their ability to harbour diverse TcI genotypes as seen in this study, clearly imply that understanding the role of the didelphids is of central importance to a more thorough elucidation of the TcI transmission cycles in Brazil.

Conclusions

We conducted a MLST study using four nuclear genes applied to a panel of TcI isolates obtained from three didelphid hosts and spanning four ecologically disparate Brazilian biomes. Our results revealed considerable intra DTU genetic diversity using a sensitive panel of MLST markers and demonstrated a lack of clear associations of TcI genotypes to geographical location or transmission cycle. The one exception are isolates from Caatinga which clustered together. These data suggest that multiple TcI genotypes circulate sympatrically in mammalian host species, transmission cycles and probably insect vectors. We also infered the presence of intralineage genetic recombination by SNP distribution patterns and phylogenies at two loci (METIII and LTY1) in two isolates derived from D. marsupialis and D. albiventris, thus substantiating the important role of didelphids in TcI transmission in Brazil.

Abbreviations

- aCD:

-

acute Chagas disease

- ColTryp:

-

Coleção de Trypanosomas de mamiferos silvestres, domesticos e vetores

- DHFR-TS :

-

Dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase

- DP:

-

Discrimination power

- DST:

-

Diploid sequence types

- DTU:

-

Discrete typing units

- ILD:

-

Incongruence length difference

- ITS:

-

Internal transcribed spacer

- LYT1 :

-

Lytic pathway protein

- MCMC:

-

Markov chain -Monte Carlo

- METIII :

-

Metacyclin-III

- MLEE:

-

Multilocus enzyme electrophoresis

- MLST:

-

Multilocus sequence typing

- NJ:

-

Neighbor-joining

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- RAPD:

-

Random amplification of polymorphic DNA

- RB19 :

-

RNA-binding protein-19

- RDP:

-

Recombination detection program

- SL-IR:

-

Spliced lader intergenic region

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- TcI:

-

Trypanosoma cruzi I

- TE:

-

Typing efficiency

References

Lent H, Wygodzinsky P. Revision of the Triatominae (Hemiptera, Reduviidae) and their significance as vectors of Chagas disease. B Am Mus Nat Hist. 1979;163:125–520.

Noireau F. Wild Triatoma infestans, a potential threat that needs to be monitored. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104(Suppl. 1):60–4.

Aguilar HM, Abad-Franch F, Dias JCP, Junqueira ACV, Coura JR. Chagas disease in the Amazon region. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2007;102(Suppl 1):47–56.

Jansen AM, Roque ALR. Domestic and wild mammalian reservoir. In: Telleria J, Tibayrenc M, editors. American trypanosomiasis Chagas disease: one hundred years of research. 2nd ed. Oxford: Elsevier; 2010. p. 249–76.

Roque ALR, Xavier SCC, da Rocha MG, Duarte AC, D’Andreas PS, Jansen AM. Trypanosoma cruzi transmission cycle among wild and domestic mammals in three areas of orally transmitted Chagas disease outbreaks. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79(5):742–9.

Coura JR, Junqueira AC, Fernandes O, Valente SA, Miles MA. Emerging Chagas disease in Amazonian Brazil. Trends Parasitol. 2002;18(4):171–6.

de Noya BA, Díaz-Bello Z, Colmenares C, Ruiz-Guevara R, Mauriello L, Zavala-Jaspe R, et al. Large urban outbreak of orally acquired acute Chagas disease at a school in Caracas, Venezuela. J Infect Dis. 2010;201(9):1308–15.

Jansen AM, Xavier SC, Roque AL. The multiple and complex and changeable scenarios of the Trypanosoma cruzi transmission cycle in the sylvatic environment. Acta Trop. 2015;151:1–15.

Macedo AM, Machado CR, Oliveira RP, Pena SD. Trypanosoma cruzi: genetic structure of populations and relevance of genetic variability to the pathogenesis of Chagas disease. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2004;99(1):1–12.

De Freitas JM, Augusto-Pinto L, Pimenta JR, Bastos-Rodrigues L, Gonçalves VF, Teixeira SMR, et al. Ancestral genomes, sex, and the population structure of Trypanosoma cruzi. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2(3):e24.

Revollo S, Oury B, Laurent J-P, Barnabé C, Quesney V, Carrière V, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi: impact of clonal evolution of the parasite on its biological and medical properties. Exp Parasitol. 1998;89(1):30–9.

Brisse S, Barnabe C, Tibayrenc M. Identification of six Trypanosoma cruzi phylogenetic lineages by random amplified polymorphic DNA and multilocus enzyme electrophoresis. Int J Parasitol. 2000;30(1):35–44.

Zingales B, Andrade SG, Briones MR, Campbell DA, Chiari E, Fernandes O, et al. A new consensus for Trypanosoma cruzi intraspecific nomenclature: a second revision meeting recommends TcI to TcVI. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104:1051–4.

Marcili A, Lima L, Cavazzana M Jr, Junqueira ACV, Veludo HH, Maia Da Silva F. A new genotype of Trypanosoma cruzi associated with bats evidenced by phylogenetic analyses using SSU rDNA, cytochrome b and histone H2B genes and genotyping based on ITS1 rDNA. Parasitology. 2009;136:641–55.

Westenberger SJ, Barnabe C, Campbell DA, Sturm NR. Two hybridization events define the population structure of Trypanosoma cruzi. Genetics. 2005;171:527–43.

Ramirez JD, Duque MC, Guhl F. Phylogenetic reconstruction based on cytochrome b (cytb) gene sequences reveals distinct genotypes within Colombian Trypanosoma cruzi I populations. Acta Trop. 2011;119(1):61–5.

Sturm NR, Vargas NS, Westenberger SJ, Zingales B, Campbell DA. Evidence for multiple hybrid groups in Trypanosoma cruzi. Int J Parasitol. 2003;33(3):269–79.

Tomasini N, Diosque P. Evolution of Trypanosoma cruzi: clarifying hybridisations, mitochondrial introgressions and phylogenetic relationships between major lineages. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2015;110(3):403–13.

León CM, Hernandez C, Montanilla M, Ramirez JD. Retrospective distribution of Trypanosoma cruzi I genotypes in Colombia. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2015;110(3):387–93.

Ramírez JD, Guhl F, Messenger L, Lewis M, Montilla M, Cucunubá Z, et al. Contemporary cryptic sexuality in Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol Ecol. 2012;21(17):4216–26.

Brenière SF, Waleckx E, Barnabé C. Over six thousand Trypanosoma cruzi strains classified into discrete typing units (DTUs): attempt at an inventory. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(8):e0004792.

Jansen AM, Santos de Pinho AP, Lisboa CV, Cupolillo E, Mangia RH, Fernandes O. The sylvatic cycle of Trypanosoma cruzi: a still unsolved puzzle. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1999;94(Suppl. 1):203–4.

O'Connor O, Bosseno MF, Barnabé C, Douzery EJ, Brenière SF. Genetic clustering of Trypanosoma cruzi I lineage evidenced by intergenic miniexon gene sequencing. Infect Genet Evol. 2007;7(5):587–93.

Souto RP, Fernandes O, Macedo AM, Campbell DA, Zingales B. DNA markers define two major phylogenetic lineages of Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;83(2):141–52.

Spotorno O AE, Córdova L, Solari IA. Differentiation of Trypanosoma cruzi I subgroups through characterization of cytochrome b gene sequences. Infect Genet Evol. 2008;8:898–900.

Salazar A, Schijman AG, Triana-Chávez O. High variability of Colombian Trypanosoma cruzi lineage I stock as revealed by low-stringency single primer-PCR minicircle signatures. Acta Trop. 2006;100(1–2):110–8.

Brandao A, Samudio F, Fernandes O, Calzada JE, Sousa OE. Genotyping of Panamanian Trypanosoma cruzi stocks using the calmodulin 3'UTR polymorphisms. Parasitol Res. 2008;102(3):523–6.

Herrera C, Bargues MD, Fajardo A, Montilla M, Triana O, Vallejo GA, Guhl F. Identifying four Trypanosoma cruzi I isolate haplotypes from different geographic regions in Colombia. Infect Genet Evol. 2007;7(4):535–9.

Falla A, Herrera C, Fajardo A, Montilla M, Vallejo G, Guhl F. Haplotype identification within Trypanosoma cruzi I in Colombian isolates from several reservoirs, vectors and humans. Acta Trop. 2009;110(1):15–21.

Cura CI, Mejía-Jaramillo AM, Duffy T, Burgos JM, Rodriguero M, Cardinal MV, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi I genotypes in different geographical regions and transmission cycles based on a microsatellite motif of the intergenic spacer of spliced-leader genes. Int J Parasitol. 2010;40(14):1599–607.

Tomasini N, Lauthier JJ, Monje Rumi MM, Ragone PG, Alberti D’Amato AA, Pérez Brandan C, et al. Interest and limitations of spliced leader intergenic region sequences for analyzing Trypanosoma cruzi I phylogenetic diversity in the Argentinean Chaco. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11(2):300–7.

Ramírez JD, Duque MC, Montilla M, Cucunubá ZM, Guhl F. Multilocus PCR-RFLP profiling in Trypanosoma cruzi I highlights an intraspecific genetic variation pattern. Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12(8):1743–50.

Herrera C, Guhl F, Falla A, Fajardo A, Montilla M, Vallejo AG, Bargues MD. Genetic variability and phylogenetic relationships within Trypanosoma cruzi I isolated in Colombia based on miniexon gene sequences. J Parasitol Res. 2009; https://doi.org/10.1155/2009/897364.

Mejía-Jaramillo AM, Peña VH, Triana-Chávez O. Trypanosoma cruzi: biological characterization of lineages I and II supports the predominance of lineage I in Colombia. Exp Parasitol. 2009;121(1):83–91.

Ramirez JD, Tapia-Calle G, Guhl F. Genetic structure of Trypanosoma cruzi in Colombia revealed by a high-throughput nuclear multilocus sequence typing (nMLST) approach. BMC Genet. 2013;14:96.

Llewellyn MS, Miles MA, Carrasco HJ, Lewis MD, Yeo M, Vargas J, et al. Genome-scale multilocus microsatellite typing of Trypanosoma cruzi discrete typing unit I reveals phylogeographic structure and specific genotypes linked to human infection. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(5):e1000410.

Ramirez JD, Hernandez C. Trypanosoma cruzi I: towards the need of genetic subdivision? Part II. Acta Trop. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.05.005.

Yeo M, Mauricio IL, Messenger LA, Lewis MD, Llewellyn MS, Acosta N, et al. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) for lineage assignment and high resolution diversity studies in Trypanosoma cruzi. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5(6):e1049.

Lauthier JJ, Tomasini N, Barnabé C, Rumi M, D’Amato AMA, Ragone PG, et al. Candidate targets for multilocus sequence typing of Trypanosoma cruzi: validation using parasite stocks from the Chaco region and a set of reference strains. Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12(2):350–8.

Mauricio IL, Yeo M, Baghaei M, Doto D, Pratlong F, Zemanova E, et al. Towards multilocus sequence typing of the Leishmania donovani complex: resolving genotypes and haplotypes for five polymorphic metabolic enzymes (ASAT, GPI, NH1, NH2, PGD). Int J Parasitol. 2006;36(7):757–69.

Messenger LA, Llewellyn MS, Bhattacharyya T, Franzén O, Lewis MD, Ramírez JD, et al. Multiple mitochondrial introgression events and heteroplasmy in Trypanosoma cruzi revealed by maxicircle MLST and next generation sequencing. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6(4):e1584.

Fernandes O, Mangia RH, Lisboa CV, Pinho AP, Morel CM, Zingales B, et al. The complexity of the sylvatic cycle of Trypanosoma cruzi in the Rio de Janeiro state (Brazil) revealed by the non-transcribed spacer of the min-exon gene. Parasitology. 1999;118:161–6.

Hall TA. Bioedit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment edit and analysis program for windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser. 1999;41:95–8.

Tomasini N, Lauthier JJ, Llewellyn MS, Diosque P. MLSTest: novel software for multi-locus sequence data analysis in eukaryotic organisms. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;20:188–96.

Diosque P, Tomasini N, Lauthier JJ, Messenger LA, Rumi MM, Ragone PG, et al. Optimized multilocus sequence typing scheme (MLST) for Trypanosoma cruzi. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(8):e3117.

Tavanti A, Gow NA, Maiden MC, Odds FC, Shaw DJ. Genetic evidence for recombination in Candida albicans based on haplotype analysis. Fungal Genet Biol. 2004;41(5):553–62.

Stephens M, Smith NJ, Donnelly P. A new statistical method for haplotype reconstruction from population data. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:978–89.

Milne I, Lindner D, Bayer M, Husmeier D, McGuire G, Marshall DF, et al. TOPALi v2: a rich graphical interface for evolutionary analyses of multiple alignments on HPC cluster and multi-core desktops. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:126–7.

Martin DP, Williamson C, Posada D. RDP2: recombination detection and analysis from sequence alignments. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:260–2.

Martin D, Rybicki E. RDP: detection of recombination amongst aligned sequences. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:562–3.

Salminen MO, Carr JK, Burke DS, McCutchan FE. Identification of breakpoints in intergenotypic recombinants of HIV type 1 by bootscanning. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1995;11:1423–5.

Sawyer S. Statistical tests for detecting gene conversion. Mol Biol Evol. 1989;6:526–38.

Posada D, Crandall KA. Evaluation of methods for detecting recombination from DNA sequences: computer simulations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13757–62.

Smith JM. Analyzing the mosaic structure of genes. J Mol Evol. 1992;34:126–9.

Gibbs MJ, Armstrong JS, Gibbs AJ. Sister-scanning: a Monte Carlo procedure for assessing signals in recombinant sequences. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:573–82.

Boni MF, Posada D, Feldman MW. An exact nonparametric method for inferring mosaic structure in sequence triplets. Genetics. 2007;176:1035–47.

Rozas M, De Doncker S, Coronado X, Barnabe C, Tibyarenc M, Solari A, Dujardin JC. Evolutionary history of Trypanosoma cruzi according to antigen genes. Parasitology. 2008;135:1157–16.

Gaunt MW, Yeo M, Frame IA, Stothard JR, Carrasco HJ, Taylor MC, et al. Mechanism of genetic exchange in American trypanosomes. Nature. 2003;421:936–9.

Ramírez JD, Llewellyn MS. Reproductive clonality in protozoan pathogens - truth or artefact? Mol Ecol. 2014;23(17):4195–202.

Tibayrenc M, Ayala FJ. Reproductive clonality of pathogens: a perspective on pathogenic viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasitic protozoa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(48):e3305–13.

Tibayrenc M, Ayala FJ. How clonal are Trypanosoma and Leishmania? Trends Parasitol. 2013;29(6):264–9.

Crouzeilles R, Lorini ML, Grelle CEV. Inter-habitat moviment for atlantic forest species and the dificulty to build ecoprofiles. Oecologia Australis. 2010;14(4):872–900.

Lima V, Jansen AM, Messenger LA, Miles MA, Llewellyn MS. Wild Trypanosoma cruzi I genetic diversity in Brazil suggests admixture and disturbance in parasite populations from the Atlantic Forest region. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:263.

Nobrega AA, Garcia MH, Tatto E, Obara MT, Costa E, Sobel J, et al. Oral transmission of Chagas disease by consumption of açaí palm fruit, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(4):653–5.

Roque AL, Xavier SCC, Gerhardt M, Silva MF, Lima VS, D'Andrea PS, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi among wild and domestic mammals in different areas of the Abaetetuba municipality (Pará State, Brazil), an endemic Chagas disease transmission area. Vet Parasitol. 2013;193(1–3):71–7.

Llewellyn MS, Rivett-Carnac JB, Fitzpatrick S, Lewis MD, Yeo M, Gaunt MW, et al. Extraordinary Trypanosoma cruzi diversity within single mammalian reservoir hosts implies a mechanism of diversifying selection. Int J Parasitol. 2011;41(6):609–14.

Xavier SCC, Roque ALR, Bilac D, de Araújo VAL, NetoSFC LES, et al. Distantiae transmission of Trypanosoma cruzi: a new epidemiological feature of acute Chagas disease in Brazil. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(5):e2878.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Valdirene Santos Lima for the support in the experimental technique. Ana Carolina Paulo Vicente and Michel Abanto, Laboratory of Molecular Genetics of Microorganisms of the Fiocruz of Rio de Janeiro, for the support in the sequencing of the samples and assistance in the collection of genetic information; to Samanta das Chagas for the collaboration with the map and the PDTIS/Fiocruz sequencing platform for sequence our samples.

Funding

A MSc master’s degree and a doctoral grant were provided by CNPq to FR. AMJ is a “Cientista do Nosso Estado”, provided by FAPERJ and is financially supported by CNPq (“Bolsista de Produtividade, nível 1”, CNPq). AMI is financially supported by CNPq e FAPERJ. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The newly generated sequences were submitted to the GenBank database under the accession numbers MG228275–MG228302 (DHFR-TS); MG228303–MG228330 (RB19); MG228331-MG228358 (LYT1) and MG868953-MG868980 (METIII).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MY designed the experiments. FR performed the experiments and wrote the first version of manuscript. AMI, AMJ and FR analyzed the results. FR, AMI, AMJ and MY contributed to the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. No special permission was required for the present study. We used DNA extracted from the cultures obtained from animals collected during previous field expeditions conducted by our group.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional files

Additional file 1

Figure S1 Phylogenetic incongruence between individual nuclear markers applied to 35 TcI Brazilian isolates. a NJ phylogenetic reconstruction using DHFR-TS. b NJ phylogenetic reconstruction using METIII. (PDF 122 kb)

Additional file 2

Figure S2 Phylogenetic incongruence between individual nuclear markers applied to 35 TcI Brazilian isolates. a NJ phylogenetic reconstruction using LYT1. b NJ phylogenetic reconstruction using RB19. (PDF 122 kb)

Additional file 3

Table S1 SNP data showing putative donor and recipient isolates for METIII. Sequences containing heterozygous SNPs (R) and putative homozygous donor (D) genotypes. (XLSX 12 kb)

Additional file 4

Table S2 SNP data showing putative donor and recipient isolates for LYT1. Sequences containing heterozygous SNPs (R) and putative homozygous donor (D) genotypes. (XLSX 8 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Roman, F., Iñiguez, A.M., Yeo, M. et al. Multilocus sequence typing: genetic diversity in Trypanosoma cruzi I (TcI) isolates from Brazilian didelphids. Parasites Vectors 11, 107 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-018-2696-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-018-2696-9