Abstract

Introduction

We have almost no information concerning the value of inferior vena cava (IVC) respiratory variations in spontaneously breathing ICU patients (SBP) to predict fluid responsiveness.

Methods

SBP with clinical fluid need were included prospectively in the study. Echocardiography and Doppler ultrasound were used to record the aortic velocity-time integral (VTI), stroke volume (SV), cardiac output (CO) and IVC collapsibility index (cIVC) ((maximum diameter (IVCmax)– minimum diameter (IVCmin))/ IVCmax) at baseline, after a passive leg-raising maneuver (PLR) and after 500 ml of saline infusion.

Results

Fifty-nine patients (30 males and 29 females; 57 ± 18 years-old) were included in the study. Of these, 29 (49 %) were considered to be responders (≥10 % increase in CO after fluid infusion). There were no significant differences between responders and nonresponders at baseline, except for a higher aortic VTI in nonresponders (16 cm vs. 19 cm, p = 0.03). Responders had a lower baseline IVCmin than nonresponders (11 ± 5 mm vs. 14 ± 5 mm, p = 0.04) and more marked IVC variations (cIVC: 35 ± 16 vs. 27 ± 10 %, p = 0.04). Prediction of fluid-responsiveness using cIVC and IVCmax was low (area under the curve for cIVC at baseline 0.62 ± 0.07; 95 %, CI 0.49-0.74 and for IVCmax at baseline 0.62 ± 0.07; 95 % CI 0.49-0.75). In contrast, IVC respiratory variations >42 % in SBP demonstrated a high specificity (97 %) and a positive predictive value (90 %) to predict an increase in CO after fluid infusion.

Conclusions

In SBP with suspected hypovolemia, vena cava size and respiratory variability do not predict fluid responsiveness. In contrast, a cIVC >42 % may predict an increase in CO after fluid infusion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypovolemia is a very frequent clinical situation in the intensive care unit (ICU) and is primarily treated with volume expansion. Unfortunately, only 40–70 % of critically ill patients with acute circulatory failure display a significant increase in their cardiac output (CO) in response to volume expansion [1]. In septic shock, fluid infusion is usually recommended [2] but may be harmful - particularly in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome [3, 4]. It is therefore essential to have reliable tools for predicting the efficacy of volume expansion and thus distinguishing patients who might benefit from volume expansion from those in whom the treatment is likely to be inefficacious. Many studies have focused on the prediction of fluid responsiveness, and many different dynamic markers of fluid responsiveness have been studied in recent years [1, 5–7]. Recent research has also demonstrated that standard static hemodynamic measurements (such as central venous pressure or pulmonary artery occlusion pressure) are of little value in predicting fluid responsiveness [1, 8]. Research has also demonstrated that inferior vena cava (IVC) diameter may predict central venous pressure in intubated, mechanically ventilated patients and in spontaneously breathing patients [9–11]. Inferior vena cava respiratory variability is known to be related to fluid-responsiveness in ICU mechanically ventilated patients and may discriminate between responder patients (i.e., in whom CO increases after fluid infusion) from nonresponders (in whom CO remains at the same level or increases only slightly) [12, 13]. However, data on the accuracy of IVC variations for predicting fluid needs in spontaneously breathing patients are scarce [14]. The aim of the present study was to determine the value of IVC respiratory variability in spontaneously breathing patients for predicting fluid responsiveness (rather than to analyze the relationship between IVC diameter and central venous pressure (CVP)).

Methods

Patients

This prospective study was performed in two ICUs at Amiens University Medical Center (Amiens, France). Nonintubated, nonventilated, spontaneously breathing patients in whom the attending physician decided to perform fluid expansion were consecutively included. The decision by the attending physician to perform fluid expansion in our unit is usually based on the following criteria: clinical signs of acute circulatory failure (systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg, urine output < 0.5 ml/kg, tachycardia, mottled skin) and/or oligoanuria (diuresis below 20 ml/h or 0.5 ml/kg/h) and/or acute kidney failure; and/or clinical and laboratory signs of extracellular dehydration. The exclusion criteria were as follows: clinical signs of hemorrhage, inability to defer fluid challenge for several minutes, arrhythmia, use of compression stockings and a contraindication to passive leg raising (PLR). The study's objectives and procedures were approved by the local investigational review board (comité de protection des personnes Nord Ouest II; Amiens, France). No consent was needed for this observational and non-interventional study.

Study design

All patients were placed in a semirecumbent position for baseline measurements. The SBP, diastolic blood pressure (DBP), pulse pressure (PP) and MBP were measured with an invasive arterial pressure monitoring system (Agilent Component Monitoring System, model M1205A (Agilent, Boeblingen, Germany) and the heart rate (HR) was recorded. Cardiac output and IVC diameters were measured using echocardiography. The bed was then automatically moved to induce PLR of 30° [15]; blood pressure values, HR, IVC diameters and CO were measured two minutes later. The patient was then returned to the initial position and 500 cc of saline solution were administered intravenously over 15 minutes. Blood pressure, HR, and echocardiographic measurements were then repeated.

Measurements

The following clinical characteristics were recorded: age, gender, Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II), weight, McCabe score, clinical problems, primary diagnosis, medical history (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiomyopathy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or pulmonary embolism). Echocardiography was performed using the HP Sonos 2000 and Philips Envisor (Philips Medical Systems, Suresnes, France). In a parasternal two-dimensional (2D) view, the aortic diameter (AoD) was measured at the aortic valve insertion (aortic annulus). The aortic area (AA) was calculated as follows: AA = (π x AoD2) / 4. In an apical five-chamber view, aortic blood flow was recorded using pulsed Doppler, with the sampling volume located at the aortic annulus. The velocity-time integral (VTI) for aortic blood flow was calculated. Stroke volume (SV) and CO were calculated as follows: SV = VTI x AA and CO = SV x HR. Aortic area was considered to be stable throughout the experiment and so was measured at baseline only. It was used to calculate CO during PLR and after fluid infusion. The reported aortic VTI was the average of three to five consecutive measurements over a single respiratory cycle.

The IVC was examined subcostally in a longitudinal section. The IVC diameter was measured in M-mode coupled to 2D mode 2 cm before the IVC joined the right atrium. The M-mode tracing was perpendicular to the IVC. The IVC collapsibility index (cIVC, which reflects the decrease in the diameter upon inspiration) was calculated as (maximum diameter on expiration (IVCmax) – minimum diameter on inspiration (IVCmin))/ IVCmax. The intra- and inter-observer variabilities in the measurement of IVC diameter were 8.4 ± 6.6 % and 5.7 ± 2.7 %, respectively. Intra-observer reproducibility was 4.9 ± 4.3 % and 4.9 ± 4.3 % for CO and VTI, respectively, and interobserver reproducibility was 4.2 ± 3.4 % and 4.2 ± 3.4 %, respectively. All measurements were performed by echocardiography-trained intensivists.

Statistical analysis

All continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to check the normality of data distribution. Relationships between variables were analyzed by linear regression. Intergroup comparisons of continuous and categorical variables were performed with Student's T test and the chi-squared test, respectively.

The patients were classified as responders (in whom CO increased by ≥ 10 % after fluid expansion compared with baseline) and nonresponders (in whom CO increased by < 10 %). Absolute values at baseline and changes in HR, pressure values, VTI (ΔVTI), SV (ΔSV), CO (ΔCO) and IVC diameter during PLR were analyzed. The correlation between these variables and changes in CO after fluid expansion and their value for predicting an increase in CO after fluid expansion were calculated by plotting a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated for all parameters and compared in a Hanley-McNeil test. Sensitivity, specificity, negative and positive predictive values, negative and positive likelihood ratios and the percentage of correct classification were calculated after defining a cut-off value. The threshold for statistical significance was set to p < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed with MedCalc software (version 12.2.1, MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium).

Results

The characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. Fifty-nine patients (30 men and 29 women; mean age: 57 ± 18) were included in the study. They were variously suffering from hypotension or acute circulatory failure (n = 16; 27 %), oligoanuria or acute kidney failure (n = 20; 34 %) or clinical and laboratory signs of dehydration (n = 23; 39 %). Thirty-nine patients (58 %) were admitted to the ICU for non-surgical reasons and 25 patients (42 %) were admitted for surgical reasons. Only two patients were taking vasoactive agents at the time of inclusion.

Twenty-nine patients (49 %) were considered to be responders, with an increase in CO of 10 % or more after fluid challenge. There were no significant differences between responders and nonresponders in terms of demographic and baseline clinical characteristics (Table 1).

The variations in hemodynamic parameters and echocardiographic indices at baseline, during PLR, and after the fluid challenge are shown in Table 2. There were no significant differences between responders and nonresponders at baseline, with the exception of higher aortic VTI in nonresponders (16 cm vs. 19 cm, respectively; p = 0.03). After fluid infusion and after PLR, VTI, SV and (by definition) CO increased in responders but remained stable in nonresponders.

The responders' and nonresponders' echocardiographic parameters for the IVC at baseline and after fluid challenge are shown in Table 3. At baseline, responders had a smaller IVCmin than nonresponders (11 ± 5 vs. 14 ± 5 mm, respectively; p = 0.04) and displayed more marked IVC variations (cIVC 35 ± 16 vs. 27 ± 10 %, p = 0.04). After volume expansion, the two groups of patients differed significantly in terms of all IVC parameters, with again a greater cIVC in responders (35 ± 16 % at baseline and 18 ± 10 % after fluid challenge).

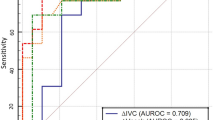

The only significant correlation was between changes in CO during PLR challenge and changes in CO after volume expansion (r = 0.69, p = 0.0001). None of the other variables were correlated with CO changes after volume expansion (Table 4). The highest AUC values were found for ΔCO (0.78 ± 0.06; 95 % confidence interval (CI) [0.66-0.88], cIVC at baseline (0.62 ± 0.07; 95 %CI 0.49-0.74) and IVCmax at baseline (0.62 ± 0.07; 95 %CI 0.49-0.75) (Table 4, Fig. 1).

Receiver operating characteristic curves for discriminating between volume expansion responders and nonresponders. ∆CO change in CO between baseline and after PLR, VCmax maximum inferior vena cava diameter at baseline, cIVC inferior vena cava collapsibility index at baseline, PLR passive leg raising

In practical terms, a reduction in IVC diameter of 42 % or more in spontaneously breathing patients distinguished between responders and nonresponders with high specificity (97 %) and a positive predictive value (90 %) but low sensitivity (Fig. 2, Table 5). We found that IVCmax at baseline had little predictive value for fluid responsiveness (Table 5, Figs. 1 and 3). However, an increase in CO of 9.5 % or more during PLR distinguished responders from nonresponders with high specificity (87 %), a high positive predictive value (79 %), low sensitivity (52 %) and low negative predictive value (65 %) (Fig. 1).

Discussion

Our results demonstrated that neither the IVC diameter nor IVC variability accurately predict fluid responsiveness in spontaneously breathing patients hospitalized in the ICU. Only inspiratory variations of IVC of 42 % or more may accurately predict an increase in CO after fluid infusion.

Echocardiography is a reliable guide to cardiac function in ICU patients - especially in cases of septic shock, in which there may be several overlapping causes of circulatory failure (e.g., hypovolemia, heart failure and vasoplegia) [16–18]. For many years, CVP was used to guide fluid infusion. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines still recommend assessing hypovolemia and fluid therapy by using CVP, which should be between 8 and 12 mmHg (2]. For a certain period of time, IVC diameter was used as a surrogate marker for right atrial pressure (RAP). Indeed, dilatation of the IVC was proven to be a reliable, sensitive marker of elevated CVP [19, 20]. The diameter of the IVC is easily recorded by transthoracic echocardiography in a subcostal view. The diameter is usually measured at end-expiration and end-diastole (with M-mode electrocardiographic (ECG) synchronization in a short-axis view, 2 cm below the right atrium) or at end-expiration (without ECG synchronization, using the two-dimensional long-axis view at the same location in the supine position) [10, 11, 21, 22]. These parameters were found to be well correlated with RAP in spontaneously breathing patients [23, 24]. Conflicting findings have been reported in mechanically ventilated patients: Benjelid et al. observed a good correlation [10], whereas Jue et al. [10] and Nagueh et al. [21] found a much weaker correlation. The IVC diameter at the cavo-atrial junction was also used to estimate CVP in a large cohort of mechanically ventilated patients [9], with a good correlation with RAP. From a practical point of view and considering these studies as a whole, a low IVC diameter (<10-12 mm) usually corresponds to low RAP (<10 mmHg) and seems to be an excellent indicator of fluid needs in patients in septic shock. In the present study, only one patient (a responder) had an IVC diameter below 10 mm.

In spontaneously breathing patients, decreased intrathoracic pressure and increased intra-abdominal pressure during inspiration increase the venous return [25]. The diameter of the IVC may then fall, due to decreased IVC transmural pressure (i.e., the intraluminal pressure less the extraluminal pressure). During insufflation (for the same intrathoracic pressure variation), higher RAP (and, therefore, a greater IVC pressure) will increase the IVC's transmural pressure, resulting in loss of IVC respiratory variability. Many researchers have reported a good correlation between RAP and IVC respiratory variability in spontaneously breathing patients [25–29]. In echocardiographic measurements, the cIVC (reflected by a caval index greater than or equal to 50 %) indicated a RAP value below 10 mmHg and caval indices below 50 % indicated a RAP value of 10 mmHg or more in the study by Kircher et al. [26]. Recently, Breenan et al. [29] reappraised the use of IVC variations to estimate the RAP; they analyzed IVCmax, IVCmin and cIVC during passive respiration and during a sniff test in which the patient was asked to perform a brief, rapid inspiration [29]. A cut-off value of 20 % for the passive cIVC and cut-off value 40 % in the sniff test were able to identify patients with RAP values less than or greater than 10 mmHg (AUC ROC: 0.93 and 0.91, respectively). In Breenan et al.'s study, a small or normal IVC diameter (<21 mm) and a sniff test result greater than 55 % were highly predictive of RAP < 10 mmHg.

In all these studies, RAP was used to assess fluid needs in patients with shock. Although an international working group [2] recently recommended the use of CVP as a marker of fluid responsiveness, this approach is highly controversial in ICU patients with shock [1, 8, 30]. In many studies, RAP and fluid responsiveness were either not correlated or only weakly correlation [1, 8]. Over the last decade, dynamic measurements (rather than static measurements) have become popular for predicting fluid responsiveness [1, 5–7, 12–16, 30–34]. Many different parameters have been found to be highly predictive of greater CO after fluid infusion in mechanically ventilated patients and spontaneously breathing patients. Vieillard Baron et al. demonstrated that the superior vena cava collapsibility index (recorded via transesophageal echocardiography) was very effective for assessing fluid needs in shocked and mechanically ventilated patients [31]. Using transthoracic echocardiography, Feissel et al. [12] and Barbier et al. [13] demonstrated that IVC variations were closely correlated with the CO increase after fluid infusion. Unfortunately, however, no information concerning the efficacy of assessing IVC in spontaneously breathing patients in terms of fluid responsiveness was reported in these publications. From a practical point of view, a cIVC of 42 % or more was a very accurate predictive marker of fluid responsiveness in spontaneously breathing patients. Neither IVCmax nor IVCmin were predictive of fluid responsiveness. These findings are similar to those recently published by Muller et al. (14) who found that cIVC > 40 % permitted the prediction of fluid responsiveness. In contrast, they found that cIVC < 40 % did not rule out fluid needs.

This study has a number of limitations. The study population was small and so a large-scale study must be conducted to confirm these findings. The CVP was not measured as a comparator for fluid responsiveness of patients, although this correlation has been widely confirmed elsewhere. Lastly, a sniff test was not performed.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we analyzed the IVC diameter and its variability in spontaneously breathing patients with suspected hypovolemia. The IVCmax was not predictive of fluid responsiveness. In contrast, we found that cIVC > 42 % may predict an increase in CO after fluid infusion in spontaneously breathing patients in the ICU.

Key messages

-

In ICU spontaneously breathing patients with hypovolemia, respiratory variations of inferior vena cava > 42 % have a high specificity to predict an increase of cardiac output after fluid infusion

Abbreviations

- AA:

-

Aortic area

- AoD:

-

Aortic diameter

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve, cIVC, Inferior vena cava collapsibility index

- CO:

-

Cardiac output

- CVP:

-

Central venous pressure

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- HR:

-

Heart rate

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IVC:

-

Inferior vena cava

- IVCmax:

-

Inferior vena cava maximum diameter

- IVCmin:

-

Inferior vena cava minimum diameter

- PLR:

-

Passive leg raising

- PP:

-

Pulse pressure

- RAP:

-

Right atrial pressure

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- SAPS II:

-

Simplified Acute Physiology Score II

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SV:

-

Stroke volume

- VTI:

-

Velocity-time integral

- ΔCO:

-

Change in SV between baseline and PLR

- ΔSV:

-

Change in SV between baseline and PLR

- ΔVTI:

-

Change in VTI between baseline and PLR

References

Michard F, Teboul JL. Predicting fluid responsiveness in ICU patients: a critical analysis of the evidence. Chest. 2002;121(6):2000–8.

Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM, Bion J, Parker MM, Jaeschke R. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:296–327.

Alsous F, Khamiees M, DeGirolamo A, Amoateng-Adjepong Y, Manthous CA. Negative fluid balance predicts survival in patients with septic shock: a retrospective pilot study. Chest. 2000;117:1749–54.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network, Wiedemann HP, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, Thompson BT, Hayden D, et al. Comparison of two fluid-management strategies in acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(24):2564–75.

Slama M, Masson H, Teboul JL, Arnout ML, Susic D, Frohlich E, et al. Respiratory variations of aortic VTI: a new index of hypovolemia and fluid responsiveness. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283(4):H1729–1733.

Feissel M, Michard F, Mangin I, Ruyer O, Faller JP, Teboul JL. Respiratory changes in aortic blood velocity as an indicator of fluid responsiveness in ventilated patients with septic shock. Chest. 2001;119(3):867–73.

Monnet X, Bleibtreu A, Ferré A, Dres M, Gharbi R, Richard C, et al. Passive leg-raising and end-expiratory occlusion tests perform better than pulse pressure variation in patients with low respiratory system compliance. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(1):152–7.

Osman D, Ridel C, Ray P, Monnet X, Anguel N, Richard C, et al. Cardiac filling pressures are not appropriate to predict hemodynamic response to volume challenge. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(1):64–8.

Arthur ME, Landolfo C, Wade M, Castresana MR. Inferior vena cava diameter (IVCD) measured with transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) can be used to derive the central venous pressure (CVP) in anesthetized mechanically ventilated patients. Echocardiography. 2009;26(2):140–9.

Jue J, Chung W, Schiller NB. Does inferior vena cava size predict right atrial pressures in patients receiving mechanical ventilation? J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1992;5(6):613–9.

Bendjelid K, Romand JA, Walder B, Suter PM, Fournier G. Correlation between measured inferior vena cava diameter and right atrial pressure depends on the echocardiographic method used in patients who are mechanically ventilated. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2002;15(9):944–9.

Feissel M, Michard F, Faller JP, Teboul JL. The respiratory variation in inferior vena cava diameter as a guide to fluid therapy. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(9):1834–7.

Barbier C, Loubières Y, Schmit C, Hayon J, Ricôme JL, Jardin F, et al. Respiratory changes in inferior vena cava diameter are helpful in predicting fluid responsiveness in ventilated septic patients. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(9):1740–6.

Muller L, Bobbia X, Toumi M, Louart G, Molinari N, Ragonnet B, et al. Respiratory variations of inferior vena cava diameter to predict fluid responsiveness in spontaneously breathing patients with acute circulatory failure: need for a cautious use. Crit Care. 2012;16(5):R188.

Teboul JL, Monnet X. Prediction of volume responsiveness in critically ill patients with spontaneous breathing activity. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2008;14(3):334–9.

Vieillard-Baron A, Slama M, Cholley B, Janvier G, Vignon P. Echocardiography in the intensive care unit: from evolution to revolution? Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(2):243–9.

Expert Round Table on Ultrasound in ICU. International expert statement on training standards for critical care ultrasonography. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37(7):1077–83.

Mayo PH, Beaulieu Y, Doelken P, Feller-Kopman D, Harrod C, Kaplan A, et al. American College of Chest Physicians/La Société de Réanimation de Langue Française statement on competence in critical care ultrasonography. Chest. 2009;135(4):1050–60.

Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a Branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18(12):1440–63.

Shala MB, D'Cruz IA, Johns C, Kaiser J, Clark R. Echocardiography of the inferior vena cava, superior vena cava, and coronary sinus in right heart failure. Echocardiography. 1998;15(8):787–94.

Nagueh SF, Kopelen HA, Zoghbi WA. Relation of mean right atrial pressure to echocardiographic and Doppler parameters of right atrial and right ventricular function. Circulation. 1996;93:1160–9.

Nakao S, Come PC, McKay RG, Ransil BJ. Effects of positional changes on inferior vena caval size and dynamics and correlations with right-sided cardiac pressure. Am J Cardiol. 1987;59(1):125–32.

Moreno FL, Hagan AD, Holmen JR, Pryor TA, Strickland RD, Castle CH. Evaluation of size and dynamics of the inferior vena cava as an index of right-sided cardiac function. Am J Cardiol. 1984;53(4):579–85.

Mintz GS, Kotler MN, Parry WR, Iskandrian AS, Kane SA. Real-time inferior vena caval ultrasonography: normal and abnormal findings and its use in assessing right-heart function. Circulation. 1981;64(5):1018–25.

Lloyd Jr TC. Effect of inspiration on inferior vena caval blood flow in dogs. J Appl Physiol. 1983;55(6):1701–8.

Kircher BJ, Himelman RB, Schiller NB. Noninvasive estimation of right atrial pressure from the inspiratory collapse of the inferior vena cava. Am J Cardiol. 1990;66(4):493–6.

Amoore JN, Santamore WP. Venous collapse and the respiratory variability in systemic venous return. Cardiovasc Res. 1994;28:472–9.

Stawicki SP, Braslow BM, Panebianco NL, Kirkpatrick JN, Gracias VH, Hayden GE et al. Intensivist use of hand-carried ultrasonography to measure IVC collapsibility in estimating intravascular volume status: correlations with CVP. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209(1):55–61.

Brennan JM, Blair JE, Goonewardena S, Ronan A, Shah D, Vasaiwala S et al. Reappraisal of the use of inferior vena cava for estimating right atrial pressure. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2007;20(7):857–61.

Marik PE, Baram M, Vahid B. Does central venous pressure predict fluid responsiveness? A systematic review of the literature and the tale of seven mares. Chest. 2008;134(1):172–8.

Vieillard-Baron A, Chergui K, Rabiller A, Peyrouset O, Page B, Beauchet A et al. Superior vena caval collapsibility as a gauge of volume status in ventilated septic patients. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(9):1734–9.

Maizel J, Airapetian N, Lorne E, Tribouilloy C, Massy Z, Slama M. Diagnosis of central hypovolemia by using passive leg raising. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(7):1133–8.

Préau S, Dewavrin F, Soland V, Bortolotti P, Colling D, Chagnon JL et al. Hemodynamic changes during a deep inspiration maneuver predict fluid responsiveness in spontaneously breathing patients. Cardiol Res Pract. 2012;2012:191807.

Mandeville JC, Colebourn CL. Can transthoracic echocardiography be used to predict fluid responsiveness in the critically ill patient? A systematic review. Crit Care Res Pract. 2012;2012:513480.

Acknowledgements

Institution in which the study was performed: Intensive Care Unit, Department of Nephrology, Amiens University Medical Center, Amiens, France, and INSERM U-1088, Jules Verne University of Picardie, Amiens, France.

Financial support: No specific funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

NAi conceived the study, included patients, and wrote a part of the manuscript; JM designed the study, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript; OA included patients, analyzed the data and revised the manuscript; YM analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript; EL performed the statistical analysis and revised the manuscript; ML participated in the design of the study and revised the manuscript; NA revised the manuscript and participated in data analysis; AS revised the manuscript and participated in data analysis; FT analyzed data and revised the manuscript; EL analyzed data and revised the manuscript; HD performed statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript; MS conceived the study and participated in the editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Airapetian, N., Maizel, J., Alyamani, O. et al. Does inferior vena cava respiratory variability predict fluid responsiveness in spontaneously breathing patients?. Crit Care 19, 400 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-015-1100-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-015-1100-9