Abstract

The increasing use of genomics to define the pattern of actionable mutations and to test and validate new therapies for individual cancer patients, and the growing application of liquid biopsy to dynamically track tumor evolution and to adapt molecularly targeted therapy according to the emergence of tumor clonal variants is shaping modern medical oncology., In order to better describe this new therapeutic paradigm we propose the term “Liquid dynamic medicine” in the place of “Personalized or Precision medicine”. Clinical validation of the “Liquid dynamic medicine” approach is best captured by N-of-1 trials where each patient acts as tester and control of truly personalized therapies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In year 1999, Langreth and Waldholz used for the first time used the terminology “personalized medicine” with the aim indeed to identify “the right drug for each unique genetic profile” [1]. Since then, the expressions “personalized medicine”, or “precision medicine” (PM) have become widely used in oncology to indicate medical procedures by which patients receive tailored interventions based on the genetic alterations found in their tumors [2]. Although attempts to attain a unique definition of PM have been made, various definitions now exist in the literature which share the common concept that a genetic test is at the basis of every PM treatment and that this genetic test is required to stratify patients into subgroups which may or may not take advantage from a medical treatment [3, 4]. It is in this context that PM is strictly based on a molecular investigation. However, this does not necessarily correspond to personalization of the care tailored to the patients’ preferences and choices, which often is the cause of confusion [5]. Hence, today the term personalized or precision medicine is interpreted in various ways by the media, health care professionals or patients [6]. Perhaps the most appropriate definition, because it is the most widely used, is the National Institutes of Health’s definition: “The use of the combined knowledge (genetic or otherwise) about a person to predict disease susceptibility, disease prognosis, or treatment response and thereby improve a person’s health” [6].

Genomic biomarker-driven therapy

Holding onto the concept of PM as a genetic biomarker-driven treatment, an increasing number of cases have been accumulated in recent years. Of these, the most cited examples include the use of imatinib for BCR-ABL positive chronic myeloid leukemia or c-Kit positive gastrointestinal tumors [7], anti-HER2 antibodies for HER2 amplified breast or gastric cancers [8], anti-EGFR antibodies for non KRAS mutated colorectal cancers [9], small molecule EGFR inhibitors for EGFR mutated lung cancers [10, 11], BRAF inhibitors or combinations of BRAF and MEK inhibitors for melanoma patients bearing BRAF mutations in their tumors [12] or ALK inhibitors for ALK or ROS translocations in lung cancer [13]. Conventional Phase III trials have shown that when patients are stratified by the use of a genetic test known as “companion diagnostics” to receive targeted therapy, patients testing “positive” for the biomarker experience a superior clinical benefit in terms of progression free survival and/or overall survival as compared to those testing “negative” for the same biomarker. This approach has often allowed accelerated market approval for the corresponding drugs [14]. It must be added that meta-analyses including a total of approximately 85,000 patients have confirmed that the genetic biomarker-driven patient selection is safe and has been associated with improvements in all outcome variables [15,16,17]. In addition, it would be considerate that the increasing use of this molecular approach in both cancer research and clinical practice, bring to a higher expense for target drugs, which are compensated by a less overall costs for the Health System coming from the better patient outcome and reduction of hospital admissions.

However, strictly speaking, these examples of PM are not truly considered “personalized medicine” since they are not tailored to individual patients, but rather to subgroups of patients sharing only one of the several genetic alterations present in their tumors.

The genetic biomarker-driven concept of PM has been challenged by a series of facts and evidence. Firstly, the presence or absence of the specific biomarker does not always result in biological and clinical sensitivity to the corresponding drug. For example, a subset of lung cancer patients which do not bear activating EGFR mutations can achieve clinical responses to EGFR inhibitors [18], or also a good proportion of BRAF mutated melanoma patients do not respond to BRAF inhibitors [19]. The case of BRAF mutations is even more intriguing because activating oncogenic BRAF mutations are found in several other tumors, including colorectal, thyroid, lung cancer but in the majority of those cases they are not predictive of drug response to the same BRAF inhibitors as in melanoma. Mechanistic explanations to these findings are emerging and reside in the presence of additional genetic or epigenetic alterations which may create from case to case “favorable” or “unfavorable” contexts to the action of a specific target therapy. This brings us to the second line of evidence: tumors are in general highly heterogeneous and mutated in several driver genes.

Interpatient and intrapatient heterogeneity

The first level of heterogeneity is interpatient heterogeneity. Tumors of the same histological origin but deriving from different patients, are genetically (and epigenetically) altered and harbor a large number of molecular alterations resulting from an evolutionary process that starts from normal cells through the clonal expansion of cells capable of overcoming the physiological control of cell growth. At this point the necessity, for true “precision oncology”, is to identify all molecular alterations (genomic or not) of cancer that can shape response to treatments [20]. Increased optimism in recent years has been generated by technical improvements and decreased costs of next generation sequencing (NGS). It is now possible, at least in theory, to use gene panels of increasing complexity to identify all driver genetic mutations by NGS and match these mutations to an ever increasing number of approved or experimental drugs capable of targeting these mutations [21, 22]. Applying of this concept is a highly challenging task because of the complexity to accumulate, store, interpret and standardize the data required to leverage genomic data that improves patient treatment [23]. However, this is not yet feasible in clinical practice at the present time and only few organizations have been able to use this approach experimentally with encouraging results [21, 22]. In addition to a highly qualified bioinformatic capable of elaborating data, it is also necessary to assemble and coordinate of a multidisciplinary tumor board comprising oncologists, radiologists, pathologists, geneticists, statisticians, mathematicians, as well as partnering up with several pharmaceutical companies to make their experimental drugs available. Hence, with a few exceptions, although we are able to identify several genomic aberrations in metastatic cancer, the utility of this information still remains largely elusive [23].

Therefore, at this moment in time we cannot talk of the realization of a true “precision medicine” approach. This may be also due to an additional reason, namely the intrapatient heterogeneity of tumors and the ability of cancer genomes to evolve dynamically over time and accumulate different subsets of mutations in different tumor subclones. Sophisticated techniques are able to construct phylogenetic trees of tumors showing the relationships among the various patterns of mutations [24]. Different subclones can change in their relative proportions with time due to selective pressures, endogenous (e.g. immunosurveillance by our immune system), or exogenous (environmental cues or drug treatments). Nowadays more than ever, we can observe as a result of the application of sequential lines of therapy often lasting years in the same metastatic patient, that cancer is becoming a chronic disease. The notion of chronicity means that cancer is continuously evolving and is genetically very different after years of therapy far from the time of the initial diagnosis.

From “personalized or precision medicine” to “liquid dynamic medicine”

One of the most important breakthroughs in the last few years is that it is now technically possible to follow tumor evolution in a non-invasive manner by a procedure called “liquid biopsy” which involves sequencing tumor DNA fragments known as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in blood samples [25]. Liquid biopsies are already in use in selected cases for diagnostic purposes (for example the detection of resistant mutations in EGFR), and we can expect a dramatic rise of clinical applications, given that they can predict disease relapse several weeks before radiological detection of disease recurrence [26]. Hence, we can expect future cancer therapies to not only be genomically driven but also continuously determined by the variations provided by the results of sequential liquid biopsies capable of tracking changes of the emerging dominant subclones to be targeted by the increasing number of matching drugs [27]. On this basis, and according to Bauman’s definition of “liquid-modern society” [28] we would like to propose to replace the expression “personalized or precision medicine” to “liquid dynamic medicine” which better describes this methodological approach. “Liquid dynamic medicine” accurately describes dynamic changes in tumor evolution which imposes dynamic changes in the therapy to apply, but also based on the fact that relevant information is present in body fluids. In the “liquid dynamic medicine” scenario patients (and their associations) play a central role and are key players as the information for therapy directly derives from their blood or other body fluids, to which they are the sole contributors. Also, central to realizing of this scenario is the capability of building and interrogating biobanks of longitudinal body fluid samples [29]. Moreover we believe that the “liquid dynamic medicine” approach will apply to the design and construction of patient-specific cancer vaccines against neoantigens a new fashionable approach to cancer therapy [30].

N-of-1 trials as a tool to implement “liquid dynamic medicine”

Toward the practical realization of this “liquid dynamic medicine” setting the use of unconventional clinical trials is required. Conventional phase I-III clinical trials along with their rigid schemes do fail to respond the need of answering more questions, more efficiently and in less time. They are unable to respond to the need of a dynamic therapy in which the biological features of the disease change with time and also where every patient, due to the growing complexity of using diagnostic testing will be differentiated from all the others. One attempt to solve this issue is by the use of the so called “Master Protocols”, designed to answer multiple questions [31]. PM’s master protocol concept challenges the traditional clinical trial infrastructure through evaluating more than one or two treatments in more than one patient type or disease within the same overall trial structure. Master protocols include umbrella, basket and platform trials. Umbrella trials are designed to study targeted therapies in the context of a single disease. Basket trials study a single targeted therapy in the context of multiple diseases or a disease subtype. Platform trials focus on multiple targeted therapies in the context of a single disease in a perpetual manner, allowing therapies to enter or leave the platform according to a decision algorithm.

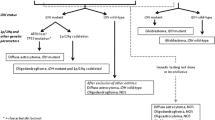

We believe however that also Master Protocols are going to reveal their limitations in the new world of “liquid dynamic medicine” and extreme personalization of care. Indeed, in cases where a combination of molecular alterations is very rare, testing the activity and efficacy of investigational drugs in a sufficient number of patients also within master protocols will be highly challenging. For example, while 5% of patients with a common malignancy (e.g., breast cancer) may be sufficient to conceive and conduct a conventional trial of a new target therapy, enrolling an adequate number of patients in a timely manner to define clinical utility would be extremely difficult if the population in question represented 1% or less of this population, and virtually impossible if one wishes to explore the benefits of treatment in rarer neoplasms. However, this goal could be possible to achieve with studies focusing on a single person – known as N-of-1 trials – which aim to study targeted treatments for tumors in individual patients (Fig. 1) [32]. The option we propose is to compare the time-to-disease progression of an individual cancer patient following treatment with a novel therapy to the time-to-disease progression for the same patient on his/her immediately previous treatment [33]. In other words, in N-of-1 trials the same patient will be the tester of a new therapy and its control arm.

Conclusion

The increasing knowledge of molecular events in cancer cells prompted the identification of targeted therapies which could be able to interfere with tumor growth. A dynamic chess mate appeared to characterize sequential molecular events developing between the onset of mechanisms of resistance and the identification of new therapeutic strategies.

In conclusion, therefore, for testing new oncology therapies based on in depth genomic characterization of patient’ tumors, we propose the use of N-of-1 trials and the promotion of the term “liquid dynamic medicine”.

References

Langreth R, Waldholz M. New era of personalized medicine targeting drugs for each unique genetic profile. Oncologist. 1999;4(5):426–7.

Personalized medicine, Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Personalized_medicine.

Redekop WK, Mladsi D. The faces of personalized medicine: a framework for understanding its meaning and scope. Value Health. 2013;6:Suppl 4–9.

Bria E, Di Maio M, Carlini P, Cuppone F, Giannarelli D, Cognetti F, Milella M. Targeting targeted agents: open issues for clinical trial design. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2009;28:66. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-9966-28-66.

Garattini L, Curto A, Freemantle N. Personalized medicine and economic evaluation in oncology: all theory and no practice? Exp Rev Pharmacoeconom Res. 2015;15(5):733–8.

National Cancer Institute. Personalized medicine. In: NCI dictionary of cancer terns; 2012. Available from: http://www.cancer.gov/dictionary?cdrid=561717.

Druker BJ, Guilhot F, O'Brien SG, Gathmann I, Kantarjian H, Gattermann N, Deininger MW, Silver RT, Goldman JM, Stone RM, et al. Five-year follow-up of patients receiving imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(23):2408–17.

Martin V, Cappuzzo F, Mazzucchelli L, Frattini M. HER2 In solid tumors: more than 10 years under the microscope; where are we now? Future Oncol. 2014;10(8):1469–86.

Vogel A, Hofheinz RD, Kubicka S, Arnold D. Treatment decisions in metastatic colorectal cancer - beyond first and second line combination therapies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;59:54–60.

Lee DH. Treatments for EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): the road to a success, paved with failures. Pharmacol Ther. 2017;174:1–21.

Sherwood J, Dearden S, Ratcliffe M, Walker J. Mutation status concordance between primary lesions and metastatic sites of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer and the impact of mutation testing methodologies: a literature review. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2015;34:92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-015-0207-9. Review

Simeone E, Grimaldi AM, Festino L, Vanella V, Palla M, Ascierto PA. Combination treatment of patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma: a new standard of care. BioDrugs. 2017;31(1):51–61.

Lin JJ, Riely GJ, Shaw AT. Targeting ALK: precision medicine takes on drug resistance. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(2):137–55.

Blackhall F, Cappuzzo F. Crizotinib: from discovery to accelerated development to front-line treatment. Ann Oncol. 2016;27 Suppl(3):35–41.

Schwaederle M, Zhao M, Lee JJ, Eggermont AM, Schilsky RL, Mendelsohn J, Lazar V, Kurzrock R. Impact of precision medicine in diverse cancers: a meta-analysis of phase II clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(32):3817–25.

Schwaederle M, Zhao M, Lee JJ, Lazar V, Leyland-Jones B, Schilsky RL, Mendelsohn J, Kurzrock R. Association of Biomarker-Based Treatment Strategies with Response Rates and Progression-Free Survival in refractory malignant Neoplasms: a meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(11):1452–9.

Falcone G, Felsani A, D'Agnano I. Signaling by exosomal microRNAs in cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2015;34:32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-015-0148-3.

Koinis F, Voutsina A, Kalikaki A, Koutsopoulos A, Lagoudaki E, Tsakalaki E, Dermitzaki EK, Kontopodis E, Pallis AG, Georgoulias V, et al. Long-term clinical benefit from salvage EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients with EGFR wild-type tumors. Clin Transl Oncol. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-017-1702-6.

Welsh SJ, Rizos H, Scolyer RA, Long GV. Resistance to combination BRAF and MEK inhibition in metastatic melanoma: where to next? Eur J Cancer. 2016;62:76–85.

Schütte M, Ogilvie LA, Rieke DT, Lange BMH, Yaspo ML, Lehrach H. Cancer precision medicine: why more is more and DNA is not enough. Public Health Genomics. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1159/000477157.

Hyman DM, Solit DB, Arcila ME, Cheng DT, Sabbatini P, Baselga J, Berger MF, Ladanyi M. Precision medicine at memorial Sloan Kettering cancer center: clinical next-generation sequencing enabling next-generation targeted therapy trials. Drug Discov Today. 2015;20(12):1422–8.

Johnson A, Zeng J, Bailey AM, Holla V, Litzenburger B, Lara-Guerra H, Mills GB, Mendelsohn J, Shaw KR, Meric-Bernstam F. The right drugs at the right time for the right patient: the MD Anderson precision oncology decision support platform. Drug Discov Today. 2015;20(12):1433–8.

Hughes KS, Ambinder EP, Hess GP, Yu PP, Bernstam EV, Routbort MJ, Clemenceau JR, Hamm JT, Febbo PG, Domchek SM, et al. Identifying health information technology needs of oncologists to facilitate the adoption of genomic medicine: recommendations from the 2016 American Society of Clinical Oncology Omics and precision oncology workshop. J Clin Oncol 2017Jul 24:JCO2017741744. doi: https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.74.1744.

Mina M, Raynaud F, Tavernari D, Battistello E, Sungalee S, Saghafinia S, Laessle T, Sanchez-Vega F, Schultz N, Oricchio E, Ciriello G. Conditional selection of genomic alterations dictates cancer evolution and Oncogenic dependencies. Cancer Cell. 2017 Aug 14;32(2):155–168.e6.

Abbosh C, Birkbak NJ, Wilson GA, Jamal-Hanjani M, Constantin T, Salari R, Le Quesne J, Moore DA, Veeriah S, Rosenthal R, et al. Phylogenetic ctDNA analysis depicts early-stage lung cancer evolution. Nature. 2017;545(7655):446–51.

Toledo RA, Cubillo A, Vega E, Garralda E, Alvarez R, de la Varga LU, Pascual JR, Sánchez G, Sarno F, Prieto SH, et al. Clinical validation of prospective liquid biopsy monitoring in patients with wild-type RAS metastatic colorectal cancer treated with FOLFIRI-cetuximab. Oncotarget. 2017;8(21):35289–300.

Bardelli A. Medical research: personalized test tracks cancer relapse. Nature. 2017;545(7655):417–8.

Bauman Z. Globalization: the human consequences. New York: Columbia University Press. September, 1998.

van Ommen GJ, Törnwall O, Bréchot C, Dagher G, Galli J, Hveem K, Landegren U, Luchinat C, Metspalu A, Nilsson C, et al. BBMRI-ERIC as a resource for pharmaceutical and life science industries: the development of biobank-based expert Centres. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23(7):893–900.

Melief CJM. Cancer: precision T-cell therapy targets tumours. Nature. 2017;547(7662):165–7.

Woodcock J, LaVange LM. Master protocols to study multiple therapies, multiple diseases, or both. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):62–70.

Demeyin WA, Frost J, Ukoumunne OC, Briscoe S, Britten N. N of 1 trials and the optimal individualisation of drug treatments: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):90. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0479-6.

Markman M, Kramer K, Alvarez RH, Weiss GJ, Ahn E, Daneker GW. Evaluating the utility of a ‘N-of-1’ precision cancer medicine strategy: the case for ‘time-to-subsequent-disease progression’. Oncology. 2016;91(6):299–301.

Acknowledgements

We thank Tania Merlino for editorial revision of the manuscript.

This article was conceived at the OECI oncology days 2017 in BRNO, 23 June 2017.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

All Authors participated in the elaboration of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional information

Nicola Silvestris and Gennaro Ciliberto are Co-first authors.

Marco A. Pierotti and Giorgio Stanta are Co-last authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Silvestris, N., Ciliberto, G., De Paoli, P. et al. Liquid dynamic medicine and N-of-1 clinical trials: a change of perspective in oncology research. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 36, 128 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-017-0598-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-017-0598-x