Abstract

Background

Increasing numbers of patients are receiving haplo-identical stem cell transplantation (haplo-SCT) for treatment of acute leukemia with reduced intensity (RIC) or myeloablative (MAC) conditioning regimens. The impact of conditioning intensity in haplo-SCT is unknown.

Methods

We performed a retrospective registry-based study comparing outcomes after T-replete haplo-SCT for patients with acute myeloid (AML) or lymphoid leukemia (ALL) after RIC (n = 271) and MAC (n = 425). Regimens were classified as MAC or RIC based on published criteria.

Results

A combination of post-transplant cyclophosphamide (PT-Cy) with one calcineurin inhibitor and mycophenolate mofetil (PT-Cy-based regimen) for graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis was used in 66 (25 %) patients in RIC and 125 (32 %) in MAC groups. Patients of RIC group were older and had been transplanted more recently and more frequently for AML with active disease at transplant. Percentage of engraftment (90 vs. 92 %; p = 0.58) and day 100 grade II to IV acute GVHD (24 vs. 29 %, p = 0.23) were not different between RIC and MAC groups. Multivariable analyses, run separately in AML and ALL, showed a trend toward higher relapse incidence with RIC in comparison to MAC in AML (hazard ratio (HR) 1.34, p = 0.09), and no difference in both AML and ALL in terms of non-relapse mortality (NRM) chronic GVHD and leukemia-free survival. There was no impact of conditioning regimen intensity in overall survival (OS) in AML (HR = 0.97, p = 0.79) but a trend for worse OS with RIC in ALL (HR = 1.44, p = 0.10). The main factor impacting outcomes was disease status at transplantation (HR ≥ 1.4, p ≤ 0.01). GVHD prophylaxis with PT-Cy-based regimen was independently associated with reduced NRM (HR 0.63, p = 0.02) without impact on relapse incidence (HR 0.99, p = 0.94).

Conclusions

These data suggest that T-replete haplo-SCT with both RIC and MAC, in particular associated with PT-Cy, are valid options in first line treatment of high risk AML or ALL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Haplo-identical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (haplo-SCT) is an attractive transplant procedure since it provides a possibility of transplantation to almost all patients needing an allogeneic SCT. Historical approaches of haplo-SCT performed with unmanipulated bone marrow stem cell grafts, standard myeloablative conditioning, and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis were associated with high risks of graft rejection and severe GVHD due to uncontrolled bi-directional recipient and donor allo-reactivity [1–4]. Although the development of T cell depleted haplo-SCT has allowed to control the risk of severe GVHD, the poor T cell immune reconstitution observed in these patients is associated with a high incidence of life-threatening infections [5–10]. In the last decade, several strategies of T cell replete bone marrow (BM) or peripheral blood (PB) haplo-SCT have been developed with both reduced intensity (RIC) and fully intensive myeloablative conditioning (MAC) regimens and variable GVHD prophylaxis strategies [11–26]. While some groups have used a combination of anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) with immunosuppressive agents with or without monoclonal antibodies such as rituximab and basiluximab [11–16], others have adopted the Baltimore’s strategy [17–26] of in vivo T cell depletion by the administration of high doses of cyclophosphamide (Cy) on days 3 and 4 post-SCT (PT-Cy). These approaches have improved immune reconstitution and reduced non-relapse mortality (NRM) of haplo-SCT [20, 27–29]. In single center experiences, these new haplo-SCT platforms allow similar transplant outcomes than allo-SCT performed with HLA-matched donors [30–37]. However, the optimal conditioning regimen for haplo-SCT in acute leukemia remains a question of debate.

In HLA-matched related or unrelated allogeneic SCT for acute leukemia, several studies have reported a dose-dependent effect of the intensity of the conditioning regimen on disease control [38–40]. In this context, the reduced risk of relapse after MAC is counterbalanced by higher NRM leading to similar overall survival in MAC and RIC [41–48]. In T-replete haplo-SCT, low risks of acute and chronic GVHD, resulting in <20 % NRM at 1 to 5 years after RIC and MAC, have been reported [17–26]. Relapse incidence, however, varies from 35 to 60 % at 1-year post-transplant and remained the major event after haplo-SCT performed with RIC and PT-Cy [17–19, 23, 26]. Although these differences could be related to disease risk at transplant [24, 25, 49], these observations raise the question of the role of the conditioning regimen intensity on leukemic control and transplant outcomes after T-replete haplo-SCT.

To address this question, we performed a large retrospective registry study to compare the transplant outcomes of 696 patients receiving a haplo-SCT after RIC (n = 271) to those transplanted after MAC (n = 425) for acute leukemia.

Results

Patient, disease, and transplant characteristics

Details of patients, disease, and transplant characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Six hundred and ninety-six patients with AL were included in the study. Two hundred and seventy-one patients received RIC and 425 MAC regimen before haplo-SCT between 2001 and 2012. Patients of the RIC group were older with median age of 53 years (range, 18–76) in comparison to 38 years (range, 18–4) for the MAC group (p < 0.0001). Only 45 % of the patients were ≤50 years of age in the RIC group vs. 70 % in the MAC group (p < 0.0001). The median follow-up of surviving patients in the RIC group was 15 (range, 1–73) months, while that of the MAC group was 22 (range, 1–142) months (p = 0.007). Significantly higher numbers of patients were transplanted for acute myeloid (AML) in the RIC than in the MAC group (80 vs. 67 %), while more lymphoid leukemia (ALL) recipients were documented in the MAC cohort (33 vs. 20 %; p < 0.0001). There were more patients in CR1 in the MAC group (41 vs. 29 %) and with active disease in RIC compared to MAC groups (47 vs. 31 %; p < 0.0001). The other pre-transplant characteristics were similar between RIC and MAC groups, and the majority of patients were transplanted from 2008 to 2012 in both groups (91.5 % in RIC and 82.6 % in MAC) (Table 1).

The indication for haplo-SCT was high risk disease in the majority of patients in both groups, with 71 and 59 % of patients in RIC and MAC groups, respectively, transplanted in advanced phase or active disease.

Details of transplant characteristics, conditioning, and GVHD prophylaxis regimens are summarized in Table 2. The majority of patients in the RIC group received PB stem cells (65 %) compared to a similar distribution of PB and BM as stem cell source in the MAC cohort (52.5 and 47.5 %, respectively; p = 0.001). The percentage of patients receiving in vivo T cell depletion, mainly performed with Thymoglobulin, was not significantly different between the two groups (p = 0.26). Apart from in vivo T cell depletion, GVHD prophylaxis consisted of the combination of one calcineurin inhibitor with mycophenolate mofetyl (MMF) alone, or in association with methotrexate (MTX) +/− Basiluximab (anti-CD25) or post-transplant cyclophosphamide (PT-Cy). A calcineurin inhibitor + MMF and/or MTX +/− Basimuximab was used in 31 and 54 % of the patients in the RIC and MAC groups, respectively, while the association of a calcineurin inhibitor + MMF with PT-Cy (PT-Cy + CsA/Tacro + MMF) was applied in 25 and 32 % of patients of the RIC and MAC groups, respectively. Another frequent combination was sirolimus and MMF, used in 33 % of patients of the RIC group (Table 2). The choice of conditioning and GVHD prophylaxis was dependent on centers’ protocols and strategies of transplantation.

Donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI) was reported in 24 (8.9 %) in RIC and 36 (8.5 %) in MAC groups. Among those, DLI was pre-emptive for 11 patients (4 % of patients) in RIC and 14 (3 %) in MAC groups.

Engraftment and GVHD

Conditioning regimen specific engraftment and GVHD are summarized in Table 3. Ninety percent of patients in the RIC group engrafted vs. 92 % in the MAC group (p = 0.58). The median day for ANC > 500/μL was 17 (range, 3–75) and 18 (range, 6–63) days in MAC and RIC groups, respectively (p = 0.007). The incidences of day 100 grade II–IV (29 vs. 24 %; p = 0.23) and III–IV (10.7 vs. 10.9 %; p = 0.96) acute GVHD were not significantly different between MAC and RIC groups, respectively. As shown in Table 5, in multivariate analysis, the only factor associated with increased grade II–IV acute GVHD was the use of PB in comparison to BM stem cells (hazard ratio (HR) 1.96; 95 % CI, 1.32–2.92; p = 0.0008). Two-year incidence of chronic GVHD was similar between the different conditioning groups: 25 % (95 % CI, 19–31) in RIC vs. 32 % (95 % CI, 28–37) in MAC groups; (p = 0.14). There was no difference of incidence of cGVHD in AML and ALL groups (Table 4). In multivariate analysis, chronic GVHD was not significantly different between RIC and MAC groups (HR 0.80; 95 % CI, 0.56–1.14; p = 0.21). The only factor associated with chronic GVHD was the use of PB in comparison to BM stem cells (HR 1.64; 95 % CI, 1.16–2.30; p = 0.005) (Table 5).

Toxicity and NRM

There was no difference in NRM at 2 years between RIC and MAC groups in univariate (33 %; 95 % CI, 29–38; after RIC vs. 31 %; 95 % CI, 27–36 after MAC; p = 0.88) and multivariate analyses (HR 0.95; 95 % CI, 0.69–1.31; p = 0.76) (Table 5) in the total population of patients. When analyzed separately, there was no difference neither between AML and ALL in univariate analysis (31.6 %; 95 % CI, 27–36; in AML vs. 33 %; 95 % CI, 28–37 in ALL; p = 0.87) (Table 4). In addition, in multivariate analysis, the intensity of the conditioning had no significant impact on NRM in AML and ALL groups (Table 5).

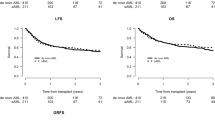

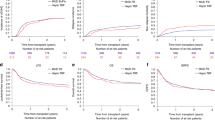

Among all patients, in univariate analysis, there was no difference in NRM at 2 years between the two groups for patients transplanted in CR1 (Table 4 and Fig. 1), in ≥CR2 or with active disease (Table 4). In multivariate analysis, however, active disease at transplant was associated with a higher risk of NRM (HR 1.86; 95 % CI, 1.34–2.59; p = 0.0002), while the use of PT-Cy + CsA/Tacro + MMF was associated with decreased NRM as compared to other GVHD prophylaxis (HR 0.63; 95 % CI, 0.44–0.92; p = 0.02) (Table 5 and Fig. 3). There was no impact of recipient age at transplant, type of disease (ALL vs. AML), source of stem cells (PB vs. BM), and year of transplant (Table 5).

The main causes of NRM were infectious complications in 53 (32 %) vs. 75 (33 %) patients and GVHD in 23 (14 %) vs. 36 (16 %) of patients in RIC vs. MAC groups, respectively. Death from organ toxicity was very low in both groups. In particular, sinusoidal obstructive syndrome (SOS) was reported in 2 (1.2 %) and 5 (2.2 %) of patients in RIC and MAC groups, respectively.

Relapse

Overall RI at 2 years was comparable between AML and ALL (36.1 % in AML and 40 % in ALL, p = 0.43) (Table 4). However, since disease status at transplant was significantly different between the two conditioning groups (Table 1), relapse incidence and survivals were analyzed separately for all patients transplanted in CR1, ≥ CR2, and with active disease (Table 4). Overall RI at 2 years for patients transplanted in CR1, ≥ CR2, and with active disease were 23.9, 33.1, and 53.6 %, respectively. In univariate analysis, RI at 2 years was similar between RIC and MAC groups for patients in CR1 (30 %; 95 % CI, 19–42 vs. 22 %; 95 % CI, 14–28 %; respectively; p = 0.21) (Table 4 and Fig. 1), in ≥CR2 (39 %; 95 % CI, 26–51 vs. 30 %; 95 % CI, 22–39 %; respectively; p = 0.38) or with active disease (56 %; 95 % CI, 47–65 vs. 52 %; 95 % CI, 42–61 %; respectively; p = 0.52) (Table 4). In multivariate analysis, there was a trend to a slight increase of RI in the RIC vs. MAC group (HR 1.31; 95 % CI, 0.98–1.75; p = 0.07) (Table 5). This trend was particularly observed in AML patients (HR 1.34; 95 % CI, 0.95–1.87; p = 0.09) (Table 5). In addition, the risk of relapse was significantly higher for patients transplanted in ≥CR2 (HR 1.46; 95 % CI, 1.01–2.13; p = 0.05) or with active disease (HR 4.43; 95 % CI, 3.20–6.12; p < 0.0001) compared to CR1, and in ALL compared to AML (HR 1.39; 95 % CI, 1.02–1.91; p = 0.04) (Table 5). Despite reduced NRM, the RI was similar in patients having received PT-Cy + CsA/Tacro + MMF in comparison to other GVHD prophylaxis (HR 0.99; 95 % CI, 0.72–1.36; p = 0.94) (Table 5 and Fig. 2).

Leukemia-free survival

LFS at 2 years was comparable between AML and ALL (32.2 % in AML and 27.2 % in ALL, p = 0.67) (Table 4). Overall LFS at 2 years for all patients transplanted in CR1, ≥CR2, and with active disease were 46.3, 35.7, and 11.4 %, respectively. LFS at 2 years was similar between RIC and MAC groups for patients transplanted in CR1 (39 %; 95 % CI, 26–51 vs. 49 %; 95 % CI, 41–57 %, respectively, p = 0.42) (Table 4 and Fig. 1) or with active disease (11 %; 95 % CI, 5–18 vs. 11 %; 95 % CI, 5–17 %, respectively, p = 0.64) (Table 4). There was a trend towards worse LFS in RIC vs. MAC groups for patients transplanted in ≥CR2 (25 %; 95 % CI, 13–36 vs. 42 %; 95 % CI, 33–52 %; respectively; p = 0.06) (Table 4). However, in multivariate analysis, LFS was no different between RIC and MAC groups for all patients (HR 1.13; 95 % CI, 0.91–1.40, p = 0.27), as well as for AML (HR 1.04; 95 % CI, 0.81–1.34, p = 0.74) and ALL (HR 1.34; 95 % CI, 0.88–2.05, p = 0.17) patients (Table 5). Multivariate analysis showed lower LFS in patients transplanted in ≥CR2 (HR 1.30; 95 % CI, 1.00–1.67; p = 0.05) or with active disease (HR 2.94; 95 % CI, 2.34–3.70; p < 0.0001) compared to CR1, and in ALL compared to AML (HR 1.28; 95 % CI, 1.02–1.61; p = 0.03) (Table 5).

Overall survival

Overall survival (OS) at 2 years was comparable between AML and ALL (37.7 % in AML and 33.3 % in ALL, p = 0.40) (Table 4). Overall OS at 2 years for patients transplanted in CR1, ≥CR2, and with active disease were 53.2, 41, and 16.3 %, respectively. OS at 2 years was similar in RIC and MAC groups for patients transplanted in CR1 (47 %; 95 % CI, 34–60 vs. 55 %; 95 % CI, 48–63 %, respectively, p = 0.64) (Table 4 and Fig. 1) or with active disease (14 %; 95 % CI, 7–21 vs. 19 %; 95 % CI, 11–26 %, respectively, p = 0.60) (Table 4 and Fig. 2). There was a trend towards worse OS in RIC as compared to MAC groups for patients transplanted in ≥CR2 (30 %; 95 % CI, 18–42 vs. 48 %; 95 % CI, 38–58 %; respectively; p = 0.07) (Table 4 and Fig. 2). In multivariate analysis, OS was no different between RIC and MAC groups in the total cohort of patients (HR 1.09; 95 % CI, 0.87–1.36, p = 0.44) (Table 5) and in AML patients (HR 0.97; 95 % CI, 0.75–1.25, p = 0.79). Although not significant, there was a trend for a worse OS with RIC in ALL patients (HR 1.44; 95 % CI, 0.94–2.22, p = 0.10) (Table 5). Of note, 39 % of ALL patients receiving a RIC had active disease at transplantation in comparison to 24 % of those transplanted with MAC (p = 0.03). Multivariate analysis also showed lower OS in patients transplanted in ≥CR2 (HR 1.40; 95 % CI, 1.07–1.83; p = 0.01) or with active disease (HR 2.92; 95 % CI, 2.30–3.72; p < 0.0001) compared to CR1, and in ALL compared to AML (HR 1.30; 95 % CI, 1.03–1.64; p = 0.03) (Table 5).

Discussion

The development of T-replete haplo-SCT for the treatment of hematological malignancies has been considerable over the last 5 to 10 years. Several RIC and MAC regimens have been designed by different groups at the same time with GVHD prophylaxis regimens based either on the Baltimore’s approach using PT-Cy [17–26] or the combination of several immunosuppressive drugs with in vivo T cell depletion with monoclonal antibodies [11–16]. They all demonstrated the feasibility of such transplants with limited NRM (≤20 % at 1 year) and promising survival rates, in particular in patients transplanted in CR [24, 25, 49]. However, comparative studies between the different transplant strategies had not been performed. Our study represents the first large retrospective analysis comparing transplant outcomes between RIC and MAC T-replete haplo-SCT for AML and ALL. In AML, our results show similar LFS and OS in patients receiving RIC and MAC regimens after adjustment for disease risk at transplant. In ALL, there was a trend for worse OS with RIC not related to increase relapse but rather a trend for increase NRM. This might be explained by higher proportions of patients with advanced disease in the RIC group.

In multivariate analysis, two factors impacted LFS and OS: disease status at transplant in all patients and in the AML and ALL subgroups (data not shown), and type of leukemia. Patients transplanted for ALL or in ≥CR2 had higher risk of relapse, while those transplanted with active disease had increased RI and NRM. Reduced anti-leukemic effect of allo-SCT with higher relapse rates in ALL in comparison to AML is well known in both non-haplo and haplo-SCT settings [50, 51]. As reported by other groups, outcome of RIC and MAC haplo-SCT in patients transplanted with active disease are poor, with relapse rates above 50 %, increased NRM, and OS below 20 % [13, 17–19, 22], confirming the need for developing innovative transplant strategies for those patients. In this series, patients transplanted in advanced disease phase (CR2 and beyond) had a higher risk of relapse and lower survival rates in comparison to those transplanted in CR1. We also observed a trend in univariate analysis towards reduced LFS and OS after RIC vs. MAC in this subset of patients. These results are in contradiction with those reported in smaller series of patients allo-grafted with RIC or MAC haplo-SCT [13, 22]. However, in their last reports, the Bacigalupo’s group also showed poorer outcome of patients transplanted in ≥CR2 [24, 32]. Our results confirm better transplant outcomes in patients transplanted in CR1 with an OS of about 50 % at 2 years, independently of the intensity of the conditioning and of recipient age (data not shown). Altogether, these results suggest that haplo-SCT should be considered in the first line of treatment in high risk AML and ALL and can be performed with MAC or RIC according to patient’s age and co-morbidities.

Cumulative incidences of acute and chronic GVHD were similar between RIC and MAC. Grade II–IV acute GVHD occurred in 25 % of patients transplanted with RIC and 29 % of those receiving a MAC, while chronic GVHD was observed in 25 and 32 % of them, respectively. These results are in line with the reported incidences of GVHD after T-replete haplo-SCT associated with different strategies of in vivo T cell depletion [13–15, 17–26] and confirm the reduction of GVHD rates with such strategies in a multicenter experience. The use of PB vs. BM stem cells was associated with increased risk of acute and chronic GVHD but had no impact on the incidence of NRM and survivals. While the use of PB is also associated with increased chronic GVHD in other HLA-matched transplant settings [52, 53], its impact on the incidence of acute GVHD is more debatable. In haplo-SCT with RIC and PT-Cy, Castagna et al. could not find significant increase of acute GVHD with PB in comparison to BM [54]. In this study, the use of PB was associated with higher risk of grade II–IV acute GVHD independently of the intensity of the conditioning regimen and of the use of PT-Cy. Because of the heterogeneity of the conditioning and GVHD prophylaxis regimens, we believe that the potential impact of the stem cell source on the incidence of acute GVHD in haplo-SCT needs further investigation.

NRM was similar between RIC and MAC groups. However, NRM was above 30 % in both groups, including in patients transplanted in CR1, which is higher than the levels below 20 % reported with T-replete haplo-SCT independently of the type of GVHD prophylaxis in single centers’ experiences [12, 13, 17–26]. Apart from disease status, the only factor impacting NRM in multivariate analysis was the use of PT-Cy in association to one calcineurin inhibitor and MMF in the prophylaxis of GVHD. NRM with PT-Cy + CsA/Tacro + MMF was closed to 20 % at 2 years (Fig. 3b), as described by the Baltimore’s group [17–19]. Reduction of NRM with PT-Cy was due to decreased mortality from GVHD (data not shown) without significant reduction in the incidence of acute and chronic GVHD, suggesting that PT-Cy ameliorates the severity of GVHD. While there was a trend for an increased incidence of relapse in RIC vs. MAC in multivariate analysis adjusted for disease risk, as observed in non-haplo-identical SCT [38–40], interestingly, patients receiving PT-Cy + CsA/Tacro + MMF did not have increased risk of relapse. Altogether, these data suggest that the association of PT-Cy with one calcineurin inhibitor and MMF represents a safer platform for GVHD prophylaxis in haplo-SCT with reduced NRM without impact on relapse incidence.

In comparison to the data reported by the Baltimore’s group of haplo-SCT performed with a Fludarabine-Cyclophosphamide-low dose TBI RIC and PT-Cy, the data of RIC with PT-Cy in this multicenter experience confirm that this approach is associated with low risks of GVHD and provides lower NRM. Although, PT-Cy is not associated to an increased risk of relapse, its incidence remains however the major post-transplant event with 30 % incidence at 2 years in patients transplanted in CR1 in our series. Thus, although this platform seems safer, strategies for improvement are needed. In this objective, adaptation of conditioning intensity, the use of PBSC together with post-transplant immunomodulation, and preventive anti-leukemia targeted strategies might improve the outcome.

Conclusions

We recognize that this study has several limitations. First, it is retrospective and registry-based with imperfectly reported cytogenetics data, and the reasons for the choice of the intensity of conditioning regimen and GVHD prophylaxis were unknown but mainly dependent on centers’ protocols and experience. Second, the conditioning regimens and GVHD prophylaxis used were very heterogeneous, and patient characteristics varied among the groups for multiple factors including age, type of leukemia, and disease status at transplantation. Despite these limitations, the results described in this large retrospective study confirm single center experiences of the validity of performing T-replete haplo-CST with MAC or RIC, in particular using PT-Cy as GVHD prophylaxis, in first line treatment of high risk AML and ALL. Prospective comparative studies are required to determine the optimal conditioning and GVHD prophylaxis as well as the place for post-transplant immunomodulation or targeted therapeutic strategies.

Methods

Study design and data collection

This was a retrospective multicenter analysis. Data were provided and approved for this study by the acute leukemia working party (ALWP) of the EBMT group registry. The latter is a voluntary working group of more than 500 transplant centers that are required to report all consecutive stem cell transplantations and follow-ups once a year. Audits are routinely performed to determine the accuracy of the data. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each site and complied with country-specific regulatory requirements. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. All patients provided written informed consent authorizing the use of their personal information for research purposes. Eligibility criteria for this analysis included adult patients (age >18 years) with AL, transplanted between 2001 and 2012, from an HLA-haplo-identical donor with bone marrow (BM) or G-CSF mobilized peripheral blood (PB) stem cells. All donors were HLA-mismatched at least at two loci (≤8/10) (-A, -B, -C, DRB1, -DQB1). Exclusion criteria were previous allogeneic or cord blood transplantation and ex vivo T cell depleted stem cell graft. Variables collected included recipient and donor characteristics (age, gender, CMV serostatus), disease status at transplant, transplant related-factors including conditioning regimen, pre-transplant immunosuppression (in vivo T cell depletion with anti-thymocyte globuline or alemtuzumab vs. none), stem cells source (BM or PB), GVHD prophylaxis (PT-Cy + CsA/Tacro + MMF vs. others), and outcome variables (acute and chronic GVHD, relapse, NRM, leukemia-free survival (LFS), OS, and causes of death). Regimens were classified as MAC or RIC based on published criteria [55]. Grading of acute and chronic GVHD was performed using established criteria [56]. Chronic GVHD was classified as limited or extensive according to usual criteria [57]. The list of institutions reporting data included in this study is provided in the supplemental data (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Statistical analysis

The primary end point of the study was overall (OS) and leukemia-free survival (LFS). Secondary endpoints included disease relapse incidence (RI), non-relapse mortality (NRM), engraftment, incidences, and severity of acute and chronic GVHD. LFS was defined as survival without relapse or progression and NRM as death without relapse/progression. The two groups according to the conditioning regimen were compared by the chi-square method for qualitative variables, whereas the Mann-Whitney test was applied for continuous parameters. Univariate comparisons were done using the log-rank test for OS, LFS, and Gray’s test for RI, NRM, and GVHD cumulative incidences. Multivariate analyses were performed using logistic regression for complete remission (CR) rate and Cox proportional hazards model for all other endpoints. Factors differing in terms of distribution between the two groups and factors associated with a p value less than 0.15 by univariate analysis were included in the final model. All tests were two-sided. The type I error rate was fixed at 0.05 for the determination of factors associated with time to event outcomes. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R 3.1.1 software packages (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

References

Beatty PG, Clift RA, Mickelson EM, Nisperos BB, Flournoy N, Martin PJ, et al. Marrow transplantation from related donors other than HLA-identical siblings. N Engl J Med. 1985;313(13):765–71.

Anasetti C, Amos D, Beatty PG, Appelbaum FR, Bensinger W, Buckner CD, et al. Effect of HLA compatibility on engraftment of bone marrow transplants in patients with leukemia or lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1989;320(4):197–204.

Anasetti C, Beatty PG, Storb R, Martin PJ, Mori M, Sanders JE, et al. Effect of HLA incompatibility on graft-versus-host disease, relapse, and survival after marrow transplantation for patients with leukemia or lymphoma. Hum Immunol. 1990;29(2):79–91.

Kanda Y, Chiba S, Hirai H, Sakamaki H, Iseki T, Kodera Y, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation from family members other than HLA-identical siblings over the last decade (1991-2000). Blood. 2003;102(4):1541–7.

Aversa F, Tabilio A, Velardi A, Cunningham I, Terenzi A, Falzetti F, et al. Treatment of high-risk acute leukemia with T-cell-depleted stem cells from related donors with one fully mismatched HLA haplotype. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(17):1186–93.

Mehta J, Singhal S, Gee AP, Chiang KY, Godder K, Rhee Fv F, et al. Bone marrow transplantation from partially HLA-mismatched family donors for acute leukemia: single-center experience of 201 patients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;33(4):389–96.

Lang P, Greil J, Bader P, Handgretinger R, Klingebiel T, Schumm M, et al. Long-term outcome after haploidentical stem cell transplantation in children. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2004;33(3):281–7.

Waller EK, Giver CR, Rosenthal H, Somani J, Langston AA, Lonial S, et al. Facilitating T-cell immune reconstitution after haploidentical transplantation in adults. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2004;33(3):233–7.

Aversa F, Terenzi A, Tabilio A, Falzetti F, Carotti A, Ballanti S, et al. Full haplotype-mismatched hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: a phase II study in patients with acute leukemia at high risk of relapse. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(15):3447–54.

Aversa F. T cell depleted haploidentical transplantation: positive selection. Pediatric reports. 2011;3 Suppl 2:e14.

Huang XJ, Liu DH, Liu KY, Xu LP, Chen H, Han W, et al. Treatment of acute leukemia with unmanipulated HLA-mismatched/haploidentical blood and bone marrow transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(2):257–65.

Wang Y, Liu DH, Liu KY, Xu LP, Zhang XH, Han W, et al. Long-term follow-up of haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation without in vitro T cell depletion for the treatment of leukemia: nine years of experience at a single center. Cancer. 2013;119(5):978–85.

Lee KH, Lee JH, Lee JH, Kim DY, Seol M, Lee YS, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning therapy with busulfan, fludarabine, and antithymocyte globulin for HLA-haploidentical hematopoietic cell transplantation in acute leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 2011;118(9):2609–17.

Di Bartolomeo P, Santarone S, De Angelis G, Picardi A, Cudillo L, Cerretti R, et al. Haploidentical, unmanipulated, G-CSF-primed bone marrow transplantation for patients with high-risk hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2013;121(5):849–57.

Arcese W, Picardi A, Santarone S, De Angelis G, Cerretti R, Cudillo L, et al. Haploidentical, G-CSF-primed, unmanipulated bone marrow transplantation for patients with high-risk hematological malignancies: an update. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50 Suppl 2:S24–30.

Peccatori J, Forcina A, Clerici D, Crocchiolo R, Vago L, Stanghellini MT, et al. Sirolimus-based graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis promotes the in vivo expansion of regulatory T cells and permits peripheral blood stem cell transplantation from haploidentical donors. Leukemia. 2015;29(2):396–405.

Luznik L, O'Donnell PV, Symons HJ, Chen AR, Leffell MS, Zahurak M, et al. HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation for hematologic malignancies using nonmyeloablative conditioning and high-dose, posttransplantation cyclophosphamide. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14(6):641–50.

Kasamon YL, Luznik L, Leffell MS, Kowalski J, Tsai HL, Bolanos-Meade J, et al. Nonmyeloablative HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation with high-dose posttransplantation cyclophosphamide: effect of HLA disparity on outcome. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16(4):482–9.

Munchel AT, Kasamon YL, Fuchs EJ. Treatment of hematological malignancies with nonmyeloablative, HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation and high dose, post-transplantation cyclophosphamide. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2011;24(3):359–68.

Ciurea SO, Mulanovich V, Saliba RM, Bayraktar UD, Jiang Y, Bassett R, et al. Improved early outcomes using a T cell replete graft compared with T cell depleted haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18(12):1835–44.

Solomon SR, Sizemore CA, Sanacore M, Zhang X, Brown S, Holland HK, et al. Haploidentical transplantation using T cell replete peripheral blood stem cells and myeloablative conditioning in patients with high-risk hematologic malignancies who lack conventional donors is well tolerated and produces excellent relapse-free survival: results of a prospective phase II trial. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18(12):1859–66.

Raiola AM, Dominietto A, Ghiso A, Di Grazia C, Lamparelli T, Gualandi F, et al. Unmanipulated haploidentical bone marrow transplantation and posttransplantation cyclophosphamide for hematologic malignancies after myeloablative conditioning. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(1):117–22.

Raiola A, Dominietto A, Varaldo R, Ghiso A, Galaverna F, Bramanti S, et al. Unmanipulated haploidentical BMT following non-myeloablative conditioning and post-transplantation CY for advanced Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49(2):190–4.

Bacigalupo A, Dominietto A, Ghiso A, Di Grazia C, Lamparelli T, Gualandi F, et al. Unmanipulated haploidentical bone marrow transplantation and post-transplant cyclophosphamide for hematologic malignanices following a myeloablative conditioning: an update. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50 Suppl 2:S37–9.

Cieri N, Greco R, Crucitti L, Morelli M, Giglio F, Levati G, et al. Post-transplantation cyclophosphamide and sirolimus after haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation using a treosulfan-based myeloablative conditioning and peripheral blood stem cells. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(8):1506–14.

Castagna L, Bramanti S, Furst S, Giordano L, Crocchiolo R, Sarina B, et al. Nonmyeloablative conditioning, unmanipulated haploidentical SCT and post-infusion CY for advanced lymphomas. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49(12):1475–80.

Tischer J, Engel N, Fritsch S, Prevalsek D, Hubmann M, Schulz C, et al. Virus infection in HLA-haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: incidence in the context of immune recovery in two different transplantation settings. Ann Hematol. 2015;94(10):1677–88.

Chang YJ, Zhao XY, Huang XJ. Immune reconstitution after haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20(4):440–9.

Shabbir-Moosajee M, Lombardi L, Ciurea SO. An overview of conditioning regimens for haploidentical stem cell transplantation with post-transplantation cyclophosphamide. Am J Hematol. 2015;90(6):541–8.

Kanakry JA, Kasamon YL, Gocke CD, Tsai HL, Davis-Sproul J, Ghosh N, et al. Outcomes of related donor HLA-identical or HLA-haploidentical allogeneic blood or marrow transplantation for peripheral T cell lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(4):602–6.

Di Stasi A, Milton DR, Poon LM, Hamdi A, Rondon G, Chen J, et al. Similar transplantation outcomes for acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome patients with haploidentical versus 10/10 human leukocyte antigen-matched unrelated and related donors. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20(12):1975–81.

Raiola AM, Dominietto A, di Grazia C, Lamparelli T, Gualandi F, Ibatici A, et al. Unmanipulated haploidentical transplants compared with other alternative donors and matched sibling grafts. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20(10):1573–9.

Blaise D, Furst S, Crocchiolo R, El-Cheikh J, Granata A, Harbi S, et al. Haploidentical T cell-replete transplantation with post-transplantation cyclophosphamide for patients in or above the sixth decade of age compared with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation from an human leukocyte antigen-matched related or unrelated donor. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(1):119–24.

Bashey A, Zhang X, Sizemore CA, Manion K, Brown S, Holland HK, et al. T-cell-replete HLA-haploidentical hematopoietic transplantation for hematologic malignancies using post-transplantation cyclophosphamide results in outcomes equivalent to those of contemporaneous HLA-matched related and unrelated donor transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(10):1310–6.

Ciurea SO, Zhang MJ, Bacigalupo AA, Bashey A, Appelbaum FR, Aljitawi OS, et al. Haploidentical transplant with posttransplant cyclophosphamide vs matched unrelated donor transplant for acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2015;126(8):1033–40.

Solomon SR, Sizemore CA, Sanacore M, Zhang X, Brown S, Holland HK, et al. Total body irradiation-based myeloablative haploidentical stem cell transplantation is a safe and effective alternative to unrelated donor transplantation in patients without matched sibling donors. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(7):1299–307.

Bashey A, Zhang X, Jackson K, Brown S, Ridgeway M, Solh M, et al. Comparison of outcomes of hematopoietic cell transplants from T-replete haploidentical donors using post-transplantation cyclophosphamide with 10 of 10 HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1, and -DQB1 allele-matched unrelated donors and HLA-identical sibling donors: a multivariable analysis including disease risk index. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(1):125–33.

Shimoni A, Hardan I, Shem-Tov N, Yeshurun M, Yerushalmi R, Avigdor A, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in AML and MDS using myeloablative versus reduced-intensity conditioning: the role of dose intensity. Leukemia. 2006;20(2):322–8.

de Lima M, Anagnostopoulos A, Munsell M, Shahjahan M, Ueno N, Ippoliti C, et al. Nonablative versus reduced-intensity conditioning regimens in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia and high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome: dose is relevant for long-term disease control after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2004;104(3):865–72.

Magenau JM, Braun T, Reddy P, Parkin B, Pawarode A, Mineishi S, et al. Allogeneic transplantation with myeloablative FluBu4 conditioning improves survival compared to reduced intensity FluBu2 conditioning for acute myeloid leukemia in remission. Ann Hematol. 2015;94(6):1033–41.

Mohty M, Labopin M, Volin L, Gratwohl A, Socie G, Esteve J, et al. Reduced-intensity versus conventional myeloablative conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplantation for patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a retrospective study from the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Blood. 2010;116(22):4439–43.

Marks DI, Wang T, Perez WS, Antin JH, Copelan E, Gale RP, et al. The outcome of full-intensity and reduced-intensity conditioning matched sibling or unrelated donor transplantation in adults with Philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first and second complete remission. Blood. 2010;116(3):366–74.

Aoudjhane M, Labopin M, Gorin NC, Shimoni A, Ruutu T, Kolb HJ, et al. Comparative outcome of reduced intensity and myeloablative conditioning regimen in HLA identical sibling allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for patients older than 50 years of age with acute myeloblastic leukaemia: a retrospective survey from the Acute Leukemia Working Party (ALWP) of the European group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). Leukemia. 2005;19(12):2304–12.

Bachanova V, Marks DI, Zhang MJ, Wang H, de Lima M, Aljurf MD, et al. Ph+ ALL patients in first complete remission have similar survival after reduced intensity and myeloablative allogeneic transplantation: impact of tyrosine kinase inhibitor and minimal residual disease. Leukemia. 2014;28(3):658–65.

Ringden O, Labopin M, Ehninger G, Niederwieser D, Olsson R, Basara N, et al. Reduced intensity conditioning compared with myeloablative conditioning using unrelated donor transplants in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(27):4570–7.

Sebert M, Porcher R, Robin M, Ades L, Boissel N, Raffoux E, et al. Equivalent outcomes using reduced intensity or conventional myeloablative conditioning transplantation for patients aged 35 years and over with AML. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014.

Abdul Wahid SF, Ismail NA, Mohd-Idris MR, Jamaluddin FW, Tumian N, Sze-Wei EY, et al. Comparison of reduced-intensity and myeloablative conditioning regimens for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a meta-analysis. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23(21):2535–52.

Bornhauser M, Kienast J, Trenschel R, Burchert A, Hegenbart U, Stadler M, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning versus standard conditioning before allogeneic haemopoietic cell transplantation in patients with acute myeloid leukaemia in first complete remission: a prospective, open-label randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(10):1035–44.

McCurdy SR, Kanakry JA, Showel MM, Tsai HL, Bolanos-Meade J, Rosner GL, et al. Risk-stratified outcomes of nonmyeloablative HLA-haploidentical BMT with high-dose posttransplantation cyclophosphamide. Blood. 2015;125(19):3024–31.

Bachanova V, Weisdorf D. Unrelated donor allogeneic transplantation for adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a review. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;41(5):455–64.

Huang X, Liu D, Liu K, Xu L, Chen H, Han W, et al. Haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation without in vitro T cell depletion for treatment of hematologic malignancies in children. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(1 Suppl):91–4.

Nagler A, Labopin M, Shimoni A, Niederwieser D, Mufti GJ, Zander AR, et al. Mobilized peripheral blood stem cells compared with bone marrow as the stem cell source for unrelated donor allogeneic transplantation with reduced-intensity conditioning in patients with acute myeloid leukemia in complete remission: an analysis from the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18(9):1422–9.

Gallardo D, de la Camara R, Nieto JB, Espigado I, Iriondo A, Jimenez-Velasco A, et al. Is mobilized peripheral blood comparable with bone marrow as a source of hematopoietic stem cells for allogeneic transplantation from HLA-identical sibling donors? A case-control study. Haematologica. 2009;94(9):1282–8.

Castagna L, Crocchiolo R, Furst S, Bramanti S, El Cheikh J, Sarina B, et al. Bone marrow compared with peripheral blood stem cells for haploidentical transplantation with a nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen and post-transplantation cyclophosphamide. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20(5):724–9.

Bacigalupo A, Ballen K, Rizzo D, Giralt S, Lazarus H, Ho V, et al. Defining the intensity of conditioning regimens: working definitions. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(12):1628–33.

Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, Klingemann HG, Beatty P, Hows J, et al. 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15(6):825–8.

Shulman HM, Sullivan KM, Weiden PL, McDonald GB, Striker GE, Sale GE, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host syndrome in man. A long-term clinicopathologic study of 20 Seattle patients. Am J Med. 1980;69(2):204–17.

Acknowledgements

MM thanks Prof. J.V. Melo (Adelaide, Australia) for critical reading of the manuscript. MM also acknowledges the educational grants received from the “Association for Training, Education and Research in Hematology, Immunology and Transplantation” (ATERHIT). The Saint-Antoine hospital group is supported by several grants from the Hospital Clinical Research Program from the French National Cancer Institute to MM.

A complete list of contributors, as well as members of the European Blood and Marrow Transplantation Group appears on the online data supplement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MTR, BNS, ML, MM, and AN designed the research and/or analyzed data; FB, AB, WA, YK, DB, ZG, DW, PDB, JT, BA, CS, and SG provided clinical data; MTR, BNS, ML, MM, and AN wrote the manuscript; and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Marie T Rubio and Bipin N Savani are joint first co-authors

Mohamad Mohty and Arnon Nagler share senior authorship

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

List of institutions reporting patients’ data for the study. (DOCX 38 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Rubio, M.T., Savani, B.N., Labopin, M. et al. Impact of conditioning intensity in T-replete haplo-identical stem cell transplantation for acute leukemia: a report from the acute leukemia working party of the EBMT. J Hematol Oncol 9, 25 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-016-0248-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-016-0248-3