Abstract

Background

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is a rare heritable connective tissue disorder primarily characterised by skeletal deformity and fragility, and an array of secondary features. The purpose of this review was to capture and quantify the published evidence relating specifically to the clinical, humanistic, and economic impact of OI on individuals, their families, and wider society.

Methods

A systematic scoping review of 11 databases (MEDLINE, MEDLINE in-progress, EMBASE, CENTRAL, PsycINFO, NHS EED, CEA Registry, PEDE, ScHARRHUd, Orphanet and Google Scholar), supplemented by hand searches of grey literature, was conducted to identify OI literature published 1st January 1995–18th December 2021. Searches were restricted to English language but without geographical limitations. The quality of included records was assessed using the AGREE II checklist and an adapted version of the JBI cross-sectional study checklist.

Results

Of the identified 7,850 records, 271 records of 245 unique studies met the inclusion criteria; overall, 168 included records examined clinical aspects of OI, 67 provided humanistic data, 6 reported on the economic impact of OI, and 30 provided data on mixed outcomes. Bone conditions, anthropometric measurements, oral conditions, diagnostic techniques, use of pharmacotherapy, and physical functioning of adults and children with OI were well described. However, few records included current care practice, diagnosis and monitoring, interactions with the healthcare system, or transition of care across life stages. Limited data on wider health concerns beyond bone health, how these concerns may impact health-related quality of life, in particular that of adult men and other family members, were identified. Few records described fatigue in children or adults. Markedly few records provided data on the socioeconomic impact of OI on patients and their caregivers, and associated costs to healthcare systems, and wider society. Most included records had qualitative limitations.

Conclusion

Despite the rarity of OI, the volume of recently published literature highlights the breadth of interest in the OI field from the research community. However, significant data gaps describing the experience of OI for individuals, their families, and wider society warrant further research to capture and quantify the full impact of OI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is a rare, heritable connective tissue disorder with multiple manifestations. Individuals with OI typically have low bone mass and skeletal fragility, and are susceptible to fractures of the long bones, vertebral compression, variable bone deformities, scoliosis and growth deficiency [1].

OI can also result in an array of secondary features including blue sclerae, hearing loss, dentinogenesis imperfecta, basilar invagination, cardiovascular and pulmonary abnormalities [1].

The condition presents as a range of phenotypes, classified according to clinical presentation, radiographic features, patterns of inheritance [2] and genetics [1]. The estimated prevalence is approximately 0.4–1.1 per 10,000 individuals based on population survey and patient registry data [3,4,5].

A multidisciplinary approach to the medical management of OI remains unrealised; current treatment aims are the reduction of fractures and improvement in mobility and function [6]. The only currently utilised pharmacologic interventions are bisphosphonates, which reduce bone turnover and may prevent or delay bone pain and reduce fracture rates, and analgesics, specifically for pain management. Non-pharmacological interventions comprise surgery, including rodding surgery, and physiotherapy [7, 8].

Living with OI may have a significant impact on the physical, social, and emotional wellbeing of individuals as well as their families and caregivers [9,10,11]. Although a sizeable body of evidence describing the impact of OI on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) exists, gaps have been identified in past records, including: an understanding of wider health concerns beyond bone health [12, 13], the impact of other manifestations of OI on HRQoL, and the impact of OI on affected family members caring for affected individuals and other family members, especially non-affected siblings. Only few studies have examined facets of the socioeconomic impact of OI on patients and their caregivers, associated costs to healthcare systems and wider society, and none currently offer a comprehensive picture of the economic impact of OI. A number of systematic literature reviews (SLRs) relating to OI have been published in the last 10 years [9, 14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]; 1 recent review reported on the impact of OI on families [9].

To our knowledge, no scoping review has comprehensively captured the breadth of the published evidence and data gaps relating to the OI patient journey. Therefore, the aim of this systematic scoping review is to capture the breadth of literature describing the clinical, HRQoL and economic impact of OI on individuals with OI, their families and caregivers, and wider society.

Methods

A systematic scoping review of the literature was performed following Centre for Reviews and Disseminations (CRD) systematic review guidance and is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendations [24, 25]. The protocol of this review has been registered with PROSPERO (registration number CRD42021225786). The data synthesis focussed on the scope of the literature following JBI recommendations for scoping reviews [26].

This systematic scoping review consisted of 3 review questions: What is the patient clinical journey as experienced by people living with OI?, What is the humanistic impact of OI as experienced by people living with OI, their families, and caregivers?, and What is the economic impact of OI as experienced by people living with OI, their families, caregivers, and healthcare providers?.

Literature searches

Eleven databases were searched for relevant records published between 1st January 1995–18th December 2021: MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), PsycINFO, National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED), Center for the Evaluation of Value and Risk in Health (CEA registry), Paediatric Economic Database Evaluation (PEDE), School of Health and Related Research Utilities Database (ScHARRHUd), Orphanet and Google Scholar. Additional manual searches of grey literature were performed. The search terms are presented in the Additional file 1: materials (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Selection of eligible studies

English language records were included if they examined the clinical impact or patient journey of adults or children with OI, the humanistic impact of OI on adults, children, or their families and caregivers, or the economic impact on individuals with OI, families and caregivers of people with OI and wider society. Primary outcomes of interest included key clinical events and health conditions, wider health concerns beyond fractures; equity concerns; socio-economic mediators for access to treatment; diagnosis and monitoring; interactions with the healthcare system; disease specific and generic HRQoL outcomes; utility measures; factors affecting HRQoL; patient reported outcomes; direct and indirect healthcare costs; healthcare resource use (HCRU); and non-healthcare costs. To answer the clinical review questions, clinical guidelines; patient registry data; patient and healthcare provider surveys; cohort studies (≥ 50 patients); cross-sectional studies (≥ 50 patients) and case–control studies (≥ 50 patients) were included. For the humanistic and economic sections, randomised-controlled trials (RCTs); non-RCTs; cohort studies; patient registry data; patient survey data; cross-sectional studies; case–control studies; case series (≥ 10 patients); economic evaluations; and HCRU or cost studies were included. A comprehensive description of eligibility criteria is provided in the Additional file 1: materials (Additional file 1: Table S2).

Duplicates were removed using Endnote algorithms and a manual screening by 1 reviewer, who also rapidly screened all titles within Endnote to remove records that clearly did not meet the eligibility criteria. At all screening stages, duplicate records, such as interim records or congress proceedings of research for which full text records were also identified, were excluded to minimise reporting bias.

Titles and abstracts of the remaining records were screened by 2 independent reviewers to identify potentially relevant records. Disagreements were resolved independently by a third reviewer. Full texts of all remaining records were screened in the same manner.

Data extraction

The following categories of data were extracted from the included studies: record identifiers, publication type, aim of the publication/study, study design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, recruitment procedures, participant characteristics (age, sex, ethnicity, country, socio-economic status, disease characteristics, comorbidities, diagnosis method), study setting (country and venue type) and outcome data or results (unit of assessment/analysis, characteristics of each pre-specified outcome, type of analysis, results of study analysis, any additional outcomes).

Quality assessment

Guidelines were assessed with the AGREE II (Appraisal for Guidelines Research and Evaluation II) checklist [27]. All other records were assessed using a custom tool adapted from the JBI (Joanna Briggs Institute) checklist for cross-sectional studies [28] (Additional file 1: Table S3).

Narrative synthesis

Included records were collated, combined, and summarised in a qualitative synthesis. Results were drawn together by category (OI patient journey/clinical impact, humanistic impact of OI, economic impact of OI) and observed effects and inconsistencies across studies were explored. Outcome data were grouped where possible to enable descriptive analysis. The narrative synthesis was undertaken by one author and reviewed by all co-authors.

For the purpose of this review, individuals younger than 18 years of age were considered children and such reports were grouped in the paediatric sections.

Results

The PRISMA diagram for the selection of eligible records is shown in Fig. 1. Overall, 271 records (67 abstracts, 204 full texts) of 245 unique studies met the inclusion criteria. Most records reported on clinical conditions (n = 168, 61.8%) (Additional file 1: Table S4), or humanistic outcomes (n = 67, 24.6%) (Additional file 1: Table S5). Only 6 records reported on economic outcomes (2.2%) (Additional file 1: Table S6). Additionally, 30 (11.1%) records reported on mixed topics (Additional file 1: Table S7).

Clinical events and conditions in individuals with OI

Overall, 171 records of 153 unique studies (47 abstracts, 124 full texts) on clinical events and conditions were included (Table 1). A detailed narrative synthesis of included records is presented in Table 1. Studies mostly used a cross-sectional design (Fig. 2). Data on children were included in 71 records (41.5%), 40 records (23.4%) included adults, and 55 (32.2%) included mixed populations. In 5 (2.9%) records the study population was unclear. Most well-described themes included bone, joint and musculoskeletal conditions (n = 97, 56.7%), anthropometric measures (n = 62, 36.3%), oral conditions (n = 45, 26.3% of records), mobility (n = 34, 19.9%), audiological conditions (n = 21, 13.5%), ophthalmological conditions (n = 29, 17.0%), cardiovascular conditions (n = 15, 8.8%) and pulmonary conditions (n = 11, 6.4%).

Less commonly described conditions included diabetes (n = 1, 0.1%), abnormal platelet counts (n = 1), gastrointestinal (GI) tract issues (n = 2, 1.2%), neurological problems (n = 2, 1.2%), kidney stones (n = 3, 1.8%), bruising and skin conditions (n = 4, 2.3%), treatment-related conditions (n = 4, 2.3%), sleep-related conditions (n = 4, 2.3%), women’s health (n = 5, 2.9%), survival (n = 5, 2.9%) and muscle strength (n = 7, 4.1%).

Diagnosis and monitoring

The diagnosis of OI was discussed in 36 records of 34 unique studies (10 abstracts, 26 full texts) (Table 2). Children were included in 15 records (41.7%), mixed populations in 16 (44.4%), adults in 3 (8.3%) [29,30,31] and an unclearly defined population in 1 (2.8%). One publication (2.8%) did not include a patient population. Best described were diagnostic techniques, including clinical history or radiographic assessment (n = 20), genetic testing (n = 10), and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scans (n = 7). Fewer records included other diagnostic techniques, such as skin biopsy or collagen analysis (n = 4), blood tests (n = 3) and prenatal diagnosis (n = 4). Equal amounts of records reported on genetic testing in 2010–2015 and 2016–2020. Additionally, age at diagnosis (n = 11), diagnostic pathways (n = 5), and misdiagnosis or diagnostic uncertainty (n = 5) were explored.

In comparison to records including data on diagnosis, fewer records describing the monitoring of patients with OI were included (n = 5; 2 abstracts, 3 full texts). Such records mostly described monitoring techniques and procedures (n = 5), including DEXA scans, vision exams, blood pressure readings, blood tests, body mass index (BMI), height or weight measurements, dental exams, bone turnover marker measurements, range of motion or patient reported measurements [13, 32,33,34,35]. One record also provided insights on monitoring frequency [35].

Current care practice

Data on current care practice were included in 74 records of 70 unique studies (12 abstracts, 62 full texts) (Table 3). Most records reported on children (n = 39, 52.7%); fewer reported on adults (n = 13, 17.6%) and mixed populations (n = 22, 29.7%). Themes included pharmacological interventions (n = 58), surgical interventions (n = 29), other interventions (n = 7) and pregnancy and birth (n = 5).

Included records on pharmacological interventions focussed on bisphosphonate use (n = 57), while the use of other medications, including vitamins or supplements (n = 10), analgesics (n = 3) or blood pressure and other medications (n = 2 each) was less well documented. Records of surgical interventions mostly included information on rodding procedures (n = 48). Other types of surgery (n ≤ 7 each for all other surgery types), use of physiotherapy (n = 5) and other non-pharmacological interventions and delivery methods (n = 5) were not well described.

Interactions with healthcare professionals

Of 15 unique records (4 abstracts, 11 full texts) [13, 30, 33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45], most included children (n = 7, 46.7%); fewer records including adults or mixed populations were identified (n = 4, 26.7% each). Records described the utilisation of services (n = 10) [13, 30, 36,37,38,39,40,41, 45, 46], experience with services (n = 3) [35, 41, 42], progression through the healthcare system (n = 2) [33, 35] and interactions with specific healthcare professionals or consultants (n = 9) [13, 33,34,35,36,37, 41,42,43]. While many records described ante- and postnatal care (n = 4) (39) [40, 45, 46], occupational and physical therapy (n = 4) [37, 41,42,43] and multidisciplinary care approaches (n = 5) [13, 33,34,35], fewer records described dental care [36] and outpatient care (n = 1 each) [38].

Guidance for clinical practice for individuals with OI

Across 13 unique, full text records of guides for clinical practice most (n = 8, 61.5%) were not specific to OI (Table 4). Of the 13 included records, 7 were published prior to 2013 and all guidance for clinical practice were published for Northern and Western Europe, the USA and Australia.

Most such records covered mixed populations (n = 9, 69.2%). 4 were specific to children (30.8%). OI-unspecific records covered the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis, skeletal dysplasias or spinal pathology, exercise recommendations for children with chronic conditions, use of bisphosphonates in children, treatment of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw and the use of DEXA scans in children with chronic disease.

The 5 OI-specific clinical practice guides (38.5%) covered the physical training and rehabilitation of children with OI, the transition of young adults from paediatric to adult care, and best practice for the molecular and genetic diagnosis of OI. Only 1 record published in 2000 described best management practices specific to OI [47].

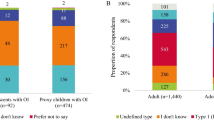

HRQoL of adults with OI

Of 32 records (2 abstracts, 30 full texts) of 48 unique studies most (n = 28) described adults (87.5%) and 4 (12.5%) mixed populations. Across studies that provided the sex of participants (n = 31), women were overrepresented (median: 59.0%). Few records focussed on young or older adults. No OI-specific tools were used; most often, results of the SF-36 tool were reported. Other tools were used in 1–3 records each (Fig. 3). Most records provided insights on the physical (n = 28) and mental health (n = 23) of adults with OI. Additionally, pain (n = 7), fatigue (n = 5) and social functioning (n = 6) were described (Fig. 3). A detailed narrative synthesis of this topic is documented in Table 5.

HRQoL of children with OI

Of 51 records (13 abstracts, 38 full texts) of 48 unique studies that described the HRQoL of children with OI, 41 records (80.4%) included children and 10 (19.6%) included a mixed population. In those records providing the sex of participants (n = 44), the proportion of male and female participants was balanced (median: 50.0%).

A variety of tools were used, none of which were OI specific (Fig. 4). Records focused predominantly on physical functioning (n = 43); fewer records included data on social functioning (n = 16), pain (n = 16) and mental health (n = 18) (Fig. 4). Few focused on fatigue (n = 3) and other domains, including cognition, speech, physical appearance, dyspnoea, overall wellbeing, eating habits, care experience and barriers to physical activity (n = 12). A detailed narrative synthesis of this topic is documented in Table 6.

Tools used to assess paediatric HRQoL domains and number of records on each domain. CHAQ Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire, HRQoL Health-related quality of life, PEDI Paediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory, PedsQL Paediatric Quality of Life Inventory, PODCI Paediatric Outcomes Data Collection Instrument, SPPC Self-Perception Profile for Children, VAS Visual Analogue Scale

HRQoL of caregivers of individuals with OI

Of 17 records of 16 unique studies (3 abstracts, 14 full texts) 14 included the sex of participants. Across such records, most participants were female (median: 66.7%). Most caregivers were either mothers or fathers to the care recipients. Two records included 4 siblings total [48, 49]. Care recipients in all studies were children; one study additionally reported on caregivers of 3 young adults (21–30 years of age) [50]. Records discussed themes of psychological wellbeing, familial and external support and relationships, care experience, physical wellbeing, and caregivers’ perception of OI (Fig. 5). The detailed narrative synthesis of this topic is documented in Table 7.

Economic outcomes of individuals with OI

Economic data were included in 11 records of 11 unique studies (2 abstracts, 9 full texts) [39, 51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60]. All featured data on the economic impact of OI, but only 7 were specific to the condition [39, 51, 53, 55, 56, 59, 60]. Seven records included children, and 2 each included adults or mixed populations. Most reported US or UK data and provided information on resource utilisation (n = 7) [39, 51, 53, 55, 57,58,59], direct medical costs (n = 10) [51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60], such as treatment and hospitalisation costs, and indirect medical costs (n = 2) [57, 60], such as out of pocket expenses and travel expenses. Few records included direct costs beyond hospitalisation-associated expenditure and resource utilisation. None included information on costs associated with co-payments or home modifications.

Quality assessment of the included studies

The majority of the included records assessed according to the JBI fell short of fulfilling all requirements (Fig. 6): for 68.5%, inclusion criteria were not reported (n = 106, 40.8%) or reported partially (n = 72, 27.7%). Most records (n = 159, 61.2%) provided partial descriptions of the study setting and subjects. For 31.5% (n = 82) the validity of the employed outcome measures was unclear. Notably, in most records, potential bias sources were not acknowledged 68.1% (n = 177) and in a further 25.0% (n = 65) they were only acknowledged partially; in most instances no strategies were employed to mitigate bias (82.3%, n = 214).

Among the 11 included guides for clinical practice in OI (Fig. 7), 54.5% (n = 6) did not provide explicit links between recommendations and supporting evidence, and 45.5% (n = 5) did not describe methods with which recommendations were formulated clearly. Furthermore 90.9% (n = 10) did not provide clear criteria for included evidence.

Discussion

This systematic scoping review provides first comprehensive overview of the available literature on the impact of OI on individuals with OI, their families, caregivers, and wider society, including clinical, humanistic, and economic data and can therefore inform future research directions.

Existing reviews of OI literature do not provide a systematic overview of the scope of published records, but rather follow a narrative design [61,62,63], or aim to answer specific research questions [9, 11, 18,19,20,21, 64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72]. Therefore, the aim of this review was to determine the breadth of literature available and provide a snapshot of the evidence it covers. With this approach, data gaps could be identified to guide the direction of future studies.

This work finds that, while the high number of identified records suggests a high research interest into OI, many aspects of the condition that affect individuals, caregivers and healthcare systems are currently insufficiently documented or understood. The quality assessment of included records found that most records did not identify, or address, bias and a considerable number did not describe inclusion criteria for study participants and evidence or included samples. This limitation is persistent across research topics and constrains the generalisability of study findings.

Additionally, the high proportion of cross-sectional study designs, reporting inconsistencies across studies, and the predominance of records from Northern America and Northern Europe hinders our understanding of the global impact of OI for individuals, families and healthcare systems.

Choosing a scoping approach allowed us to capture the breadth of evidence on OI, both quantitative and qualitative, thereby allowing us to identify some rarely reported research. However, the diversity and high number of included records limited the depth of analysis we were able to undertake. Additionally, the focus on English language records presents a limitation which we have attempted to mitigate through the inclusion of a wide variety of databases.

While some clinical conditions, such as bone-related events and conditions are well-documented, others that may negatively affect the HRQoL of individuals with OI, are often not covered in the literature. This systematic scoping review uncovered limited information on women’s health, treatment-related adverse events, and pulmonary-, GI-, kidney-, sleep-, and skin-related conditions.

Recent publications underline the importance of research into the conditions identified as data gaps in this field: in one study individuals reported that their HRQoL has been affected by urinary tract, skin, GI, and neurological conditions [13]. Additionally, other studies point to pulmonary conditions being among the most commonly reported causes of death in individuals with OI [73, 74]. Furthermore, understanding the benefits and adverse effects of treatments for individuals with rare metabolic conditions has been identified as a priority research question in a joint collaboration of patients, carers and healthcare professionals [75].

We identified few records of interactions with the healthcare system, the majority of which included data from North-western Europe or Northern America. Of those, few records included patients’ experience with services and their progression through the healthcare system. In records that described interactions with healthcare professionals, few described genetic testing, outpatient care, operative interventions, and dental care. Similarly, few included records included information on prenatal testing, blood and DNA analysis, and misdiagnosis or diagnostic uncertainty. The monitoring of individuals with OI or ongoing care was not well documented. Similarly, guidance on most care topics for individuals with OI is limited and often unspecific to OI.

HRQoL is well documented for individuals with OI, however more records of women and children, especially with milder OI types, were identified, while fewer records of young adults, men, and those with OI types 3 and 4 were found. A variety of tools were applied in the studies, which limits our ability to compare and generalise findings across studies. Few adult studies used tools that were specific to long-term disability, pain, or fatigue associated with long-term conditions, but physical and mental functioning were well described. Among paediatric records, use of disability-specific tools to assess physical functioning was prevalent, however, pain, fatigue, and mental health in children with OI were not well described.

Records on the HRQoL of caregivers featured a high number of interview-based studies and limited documentation of caregiver- and care-recipient characteristics, which may hinder the generalisability of study findings. Furthermore, few records included fathers, siblings and other family members or families of young adult and adult care recipients.

Few records included data on the economic impact of OI on individuals, healthcare systems and wider society. Most focussed on hospitalisation and associated costs, whereas indirect costs, and outpatient care consumption and costs are less well documented. Therefore, the identified data does not allow an accurate assessment of OI-associated costs and expenses.

Patient groups are unequally represented across outcomes assessed in this review: more records described clinical conditions, current care practice and HRQoL in children; similarly, OI specific clinical practice guidelines were mostly available for children or adolescents. In patient HQoL studies adult men, adolescents and older adults were underrepresented. Few studies provided data on the wellbeing of male caregivers or family members of individuals with OI. The lack of evidence for these population groups compromises any attempts at evidence-based care and is well documented to decrease the generalisability of findings, quality of care and hinder the access to effective interventions [76].

Conclusion

This work shows that despite the interest of the research community and the persistent patient need, many research areas remain to be explored to better understand the impact of OI and accurately depict individuals’ experiences. Among such gaps, future research into health concerns beyond bone health, the long-term effects of OI treatment and changing medical needs throughout an individual’s life can help to better understand and care for individuals with the condition. Additionally, a better understanding of pain and fatigue experiences, as well as the HRQoL of caregivers and families affected by OI, can aid in planning and directing services. Lastly, OI may pose a considerable economic burden to individuals and society; however, few records assess the costs associated with OI treatment and care outside of the hospital setting. An in-depth documentation of such costs could help to address concerns of affected individuals and their families.

Funding and resources for research on rare diseases are limited. However, this review represents a first step to mitigate data paucity through the identification of specific research gaps within OI. Based on these gaps we have designed and conducted an online-based survey targeted at individuals with OI, their caregivers, and close relatives [77]. We hope that the findings from the survey will help the healthcare community gain insights into the clinical, economic, and humanistic burden of this condition.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ADL:

-

Activities of daily living

- AGREE:

-

Appraisal of guidelines research evaluation

- APEG:

-

Australasian paediatric endocrine group

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CEA:

-

Center for the evaluation of value and risk in health

- CENTRAL:

-

Cochrane central register of controlled trials

- CHAQ:

-

Childhood health assessment questionnaire

- CRD:

-

Centre for reviews and dissemination

- DEXA:

-

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

- EMQN:

-

European molecular genetics quality network

- EQ-5D-5L:

-

Euroqol 5-dimension questionnaire 5 levels

- FIM:

-

Functional independence measure

- GI:

-

Gastrointestinal

- HCP:

-

Health care professional

- HCRU:

-

Healthcare resource use

- HRQoL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- JBI:

-

Joanna Briggs Institute

- MoD:

-

Mode of delivery

- NHS EED:

-

National health service economic evaluation database

- OI:

-

Osteogenesis imperfecta

- PEDE:

-

Paediatric economic database evaluation

- PEDI:

-

Paediatric evaluation of disability inventory

- PedsQL:

-

Paediatric quality of life inventory

- PODCI:

-

Paediatric outcomes data collection instrument

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- PROMIS:

-

Patient-reported outcomes measurement

- PROSPERO:

-

International prospective register of systematic reviews

- RCT:

-

Randomised controlled trial

- ScHARRHUd:

-

School of health and related research utilities database

- SF-36:

-

Short Form 36

- SPPC:

-

Self-perception profile for children

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

References

Marini JC, et al. Osteogenesis imperfecta. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17052.

Sillence DO, Senn A, Danks DM. Genetic heterogeneity in osteogenesis imperfecta. J Med Genet. 1979;16(2):101–16.

Orioli IM, Castilla EE, Barbosa-Neto JG. The birth prevalence rates for the skeletal dysplasias. J Med Genet. 1986;23(4):328–32.

Stevenson DA, et al. Analysis of skeletal dysplasias in the Utah population. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158(5):1046–54.

Andersen PE, Hauge M. Osteogenesis imperfecta: a genetic, radiological, and epidemiological study. Clinic Genetics. 1989;36(4):250–5.

Thomas IH, DiMeglio LA. Advances in the classification and treatment of osteogenesis imperfecta. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2016;14(1):1–9.

Marr C, Seasman A, Bishop N. Managing the patient with osteogenesis imperfecta: a multidisciplinary approach. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2017;10:145–55.

Brizola E, T Felix, and J Shapiro, Pathophysiology and therapeutic options in osteogenesis imperfecta: an update. Research and reports in endocrine disorders, 2016.

Hill M, et al. Exploring the impact of osteogenesis imperfecta on families: a mixed-methods systematic review. Disabil Health J. 2019;12(3):340–9.

Dogba MJ, et al. The impact of severe osteogenesis imperfecta on the lives of young patients and their parents - a qualitative analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:153.

Tsimicalis A, et al. The psychosocial experience of individuals living with osteogenesis imperfecta: a mixed-methods systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(8):1877–96.

Swezey T, et al. Incorporating the patient perspective in the study of rare bone disease: insights from the osteogenesis imperfecta community. Osteoporos Int. 2019;30(2):507–11.

Tosi LL, et al. Initial report of the osteogenesis imperfecta adult natural history initiative. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:146.

Hennedige AA, et al. Systematic review on the incidence of bisphosphonate related osteonecrosis of the jaw in children diagnosed with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Oral Maxillofac Res. 2013;4(4): e1.

Ashournia H, et al. Heart disease in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta - a systematic review. Int J Cardiol. 2015;196:149–57.

Rijks EB, et al. Efficacy and safety of bisphosphonate therapy in children with osteogenesis imperfecta: a systematic review. Horm Res Paediatr. 2015;84(1):26–42.

Sinikumpu JJ, et al. Severe osteogenesis imperfecta type-III and its challenging treatment in newborn and preschool children. A Syst Rev Injury. 2015;46(8):1440–6.

Shi CG, Zhang Y, Yuan W. Efficacy of bisphosphonates on bone mineral density and fracture rate in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Ther. 2016;23(3):e894-904.

Sá-Caputo DC, et al. Whole-body vibration exercise improves functional parameters in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta: a systematic review with a suitable approach. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2017;14(3):199–208.

Constantino CS, et al. Effect of bisphosphonates on function and mobility among children with osteogenesis imperfecta: a systematic review. JBMR Plus. 2019;3(10): e10216.

Celin MR, et al. Do bisphosphonates alleviate pain in children? Syst Rev Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2020;18(5):486–504.

Contaldo M, et al. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws and dental surgery procedures in children and young people with osteogenesis imperfecta: a systematic review. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;121(5):552.

Holme TJ, et al. Paediatric olecranon fractures: a systematic review. EFORT Open Rev. 2020;5(5):280–8.

Moher D, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339: b2535.

Tacconelli E. Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(4):226.

Peters MDJ, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis. 2020;18(10):2119–26.

Brouwers MC, Kerkvliet K, Spithoff K. The AGREE reporting checklist: a tool to improve reporting of clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016;352: i1152.

Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E, Sears K, Sfetcu R, Currie M, Qureshi R, Mattis P, Lisy K, Mu PF. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. Joanna briggs institute reviewer's manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute. 2017;5.

Dar S et al Management of osteogenesis imperfecta in adulthood-a single centre experience. Society for …, 2018.

Stewart S, et al. Birth and growth of the multidiscipl inary osteogenesis imperfecta service. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:S589.

Wekre LL, et al. A population-based study of demographical variables and ability to perform activities of daily living in adults with osteogenesis imperfecta. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(7):579–87.

Sepúlveda AM, et al. Vertebral fractures in children with type I osteogenesis imperfecta. Revista Chilena de Pediatria. 2017;88(3):348–53.

Hagberg M K Lowing, and B Malmgren Team management of young persons with osteogenesis imperfecta. European Calcified …, 2014.

Narayanan VK, et al. A survey of current care for children and adults with osteogenesis imperfecta in glasgow. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97:A102–3.

Aubry-Rozier B, et al. Osteogenesis imperfecta: towards an individualised interdisciplinary care strategy to improve physical activity and quality of life. Swiss Med Wkly. 2020;150: w20285.

Clark R, Burren CP, John R. Challenges of delivery of dental care and dental pathologies in children and young people with osteogenesis imperfecta. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2019;20(5):473–80.

Hoyer-Kuhn H, et al. A specialized rehabilitation approach improves mobility in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2014;14(4):445–53.

de Graaff F, et al. Decrease in outpatient department visits and operative interventions due to bisphosphonates in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Child Orthop. 2011;5(2):121–5.

Ruiter-Ligeti J, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in women with osteogenesis imperfecta: a retrospective cohort study. J Perinatol. 2016;36(10):828–31.

Bellur S, et al. Cesarean delivery is not associated with decreased at-birth fracture rates in osteogenesis imperfecta. Genet Med. 2016;18(6):570–6.

Galloway P, A Nixon, and L Rayner Assessment of multidisciplinary care of children with osteogenesis imperfecta at The Royal Manchester Children. 9th International …, 2019.

Moreira CLM, ACB Gilbert, and M Lima Physiotherapy and patients with osteogenesis imperfecta: an experience report. Fisioterapia em …. 2015: SciELO Brasil.

Moreira C, M Angelica, and F D Lima (2011) Independent walk in osteogenesis imperfecta. Acta Ortop …. 2011: pdfs.semanticscholar.org.

Ali AS, et al. Bisphosphonate therapy improves biochemical, radiological and clinical parameters in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. Pakistan Paediatric J. 2010;34(3):148–53.

Yimgang DP, Shapiro JR. Pregnancy outcomes in women with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29(14):2358–62.

Yimgang DP, Brizola E, Shapiro JR. Health outcomes of neonates with osteogenesis imperfecta: a cross-sectional study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29(23):3889–93.

Antoniazzi F, et al. Osteogenesis imperfecta: practical treatment guidelines. Paediatr Drugs. 2000;2(6):465–88.

Wiggins S, Kreikemeier R. Bisphosphonate therapy and osteogenesis imperfecta: the lived experience of children and their mothers. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2017;22(4):12192.

Santos MCD, et al. Family experience with osteogenesis imperfecta type 1: the most distressing situations. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(19):2281–7.

Dogba MJ, et al. Involving families with osteogenesis imperfecta in health service research: joint development of the OI/ECE questionnaire. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(1): e0147654.

Darbà J and A Marsà Hospital incidence, management and direct cost of osteogenesis imperfecta in Spain: a retrospective database analysis. J Med Econ 2020; 23(12): 1–6.

Forestier-Zhang L, et al. Health-related quality of life and a cost-utility simulation of adults in the UK with osteogenesis imperfecta, X-linked hypophosphatemia and fibrous dysplasia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2016;11(1):160.

Belyea CM, Knox JB. Spinal fusion in children with osteogenesis imperfecta: a nationwide retrospective comparative cohort study over a 12-year period. Current Orthopaedic Practice. 2020;31(1):72–5.

Rush ET, et al. Evaluation and comparison of safety, convenience and cost of administering intravenous pamidronate infusions to children in the home and ambulatory care settings. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2012;25(5–6):493–7.

Kolovos S and M K Javaid Hospital admissions of patients with osteogenesis imperfecta in the English NHS. Osteoporosis …. 2020: ora.ox.ac.uk.

Meena BL, Panigrahi I, Marwaha RK. Vitamin d deficiency in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99:A275.

Saraff V, et al. Efficacy and treatment costs of zoledronate versus pamidronate in paediatric osteoporosis. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103(1):92–4.

Kreikemeier RM, Gosnell H, Halbur LM, Rush ET. A retrospective review of initial bisphosphonate infusion in an inpatient vs. outpatient setting for bisphosphonate naïve patients. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metabolism. 2017;30(10):1105–10.

Vitale MG, et al. Osteogenesis imperfecta: determining the demographics and the predictors of death from an inpatient population. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(2):228–32.

Murphy A, A Howard, and E Sochett Financial burden in families of children with osteogenesis imperfecta (OI). 8th International …, 2017.

Kopplin E, Watkins E. Osteogenesis imperfecta: a review of denosumab research. JBJS J Orthopaedics Phys Assist. 2021;9(1):2000033.

Carré F, et al. Hearing impairment and osteogenesis imperfecta: literature review. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2019;136(5):379–83.

Rousseau M, Retrouvey JM. Osteogenesis imperfecta: potential therapeutic approaches. PeerJ. 2018;6: e5464.

Dahan-Oliel N, et al. Quality of life in osteogenesis imperfecta: a mixed-methods systematic review. Am J Med Genet A. 2016;170(1):62–76.

Nghiem T, et al. Pain experiences of children and adolescents with osteogenesis imperfecta: an integrative review. Clin J Pain. 2017;33(3):271–80.

Scollan JP, et al. The outcomes of nonelongating intramedullary fixation of the lower extremity for pediatric osteogenesis imperfecta patients: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2017;37(5):e313–6.

Sridharan K, Sivaramakrishnan G. Interventions for improving bone mineral density and reducing fracture risk in osteogenesis imperfecta: a mixed treatment comparison network meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2018;13(3):190–8.

Ying ZM, Hu B, Yan SG. Oral bisphosphonate therapy for osteogenesis imperfecta: a systematic review and meta-analysis of six randomized placebo-controlled trials. Orthop Surg. 2020;12(4):1293–303.

Dwan K, et al. Bisphosphonate therapy for osteogenesis imperfecta. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;7:CD005088.

Li G, et al. Systematic review of the effect of denosumab on children with osteogenesis imperfecta showed inconsistent findings. Acta Paediatr. 2018;107(3):534–7.

Nghiem T, et al. Pain experiences of adults with osteogenesis imperfecta: an integrative review. Canadian J Pain. 2018;2(1):9–20.

Prado HV, Teixeira SA, Rabello F, Vargas-Ferreira F, Borges-Oliveira AC, Abreu LG. Malocclusion in individuals with osteogenesis imperfecta: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis. 2022;28(2):314–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.13715

McAllion SJ, Paterson CR. Causes of death in osteogenesis imperfecta. J Clin Pathol. 1996;49(8):627–30.

Folkestad L, et al. Mortality and causes of death in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta: a register-based nationwide cohort study. J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31(12):2159–66.

Mickute G, et al. Rare musculoskeletal diseases in adults: a research priority setting partnership with the James Lind Alliance. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15(1):117.

National Academies of Sciences, E. and Medicine, improving representation in clinical trials and research: building research equity for women and underrepresented groups, ed. K. Bibbins-Domingo and A. Helman. 2022, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 280.

Rauch, F. The IMPACT survey has produced a self-reported, 2,276-respondent dataset of individuals with OI, their caregivers and close relatives. in 14th international conference on osteogenesis imperfecta. 2022. Dublin.

Goudriaan WA, et al. Incidence and treatment of femur fractures in adults with osteogenesis imperfecta: an analysis of an expert clinic of 216 patients. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2020;46(1):165–71.

Lindahl K, et al. Genetic epidemiology, prevalence, and genotype-phenotype correlations in the Swedish population with osteogenesis imperfecta. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23(8):1042–50.

Hald J D, L Folkestad, and J Andersen, Osteogenesis imperfecta in adults: a cross sectional trial. European Calcified …, 2014.

Hoseinbeyki M, S Moradifard, and F Mirkhani A preliminary data of a prospective study on Iranian patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. 9th International …, 2019.

Hupin E, K Edwards, and M Chueng Do children with mild to moderate osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) with abdominal muscle weakness have a higher incidence of pars defects? A physiotherapy pilot. 7th International …, 2015.

Kadhim M, et al, Vitamin D status in pediatric patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. Pediatr Therapeut …. 2011: researchgate.net.

Oduah G O, The clinical presentation and management of South African children with osteogenesis imperfecta. 2014: wiredspace.wits.ac.za.

Oduah GO, GB Firth, and JM Pettifor, Management of osteogenesis imperfecta at the Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital. SA Orthopaedic Journal. 2017: scielo.org.za.

Rusinska A. and I Michalus, Difficulties in diagnostics and clinical classification of osteogenesis imperfecta in Poland. 8th International …, 2017.

Scheres LJ. Bone mass density, bone metabolism, lifetime fractures and bisphosphonate use in an adult Osteogenesis Imperfecta population: an explorative study (Doctoral dissertation). 2014: umcg.studenttheses.ub.rug.nl.

Yakhyaeva G and L Namazova-Baranova, Osteogenesis imperfecta in children in the Russian Federation. Community, Diversity …, 2016.

Castro LC, et al. Osteogenesis imperfecta - clinical outcomes after a 4-year experience with cyclical intravenous pamidronate therapy. Bone. 2009;45:S59.

Binh HD, et al. The clinical features of osteogenesis imperfecta in Vietnam. Int Orthop. 2017;41(1):21–9.

Payet J, Cormier C. Clinical characteristics and vitamin D insufficiency in a population of 54 adults with osteogenesis imperfecta. Annals Rheumatic Disease. 2013;71:441.

Hatz D, et al. The incidence of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011;31(6):655–60.

Swinnen FK, et al. Association between bone mineral density and hearing loss in osteogenesis imperfecta. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(2):401–8.

Peddada KV, et al. Fracture patterns differ between osteogenesis imperfecta and routine pediatric fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2018;38(4):e207–12.

Tayne S, Smith PA. Olecranon fractures in pediatric patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Pediatr Orthop. 2019;39(7):e558–62.

Hald JD, et al. Osteogenesis imperfecta and the teeth, eyes, and ears-a study of non-skeletal phenotypes in adults. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29(12):2781–9.

Engelbert RH, et al. Osteogenesis imperfecta in childhood: prognosis for walking. J Pediatr. 2000;137(3):397–402.

Charnas LR, Marini JC. Neurologic profile in osteogenesis imperfecta. Connect Tissue Res. 1995;31(4):S23–6.

Li M, et al. Efficacy of alendronate on children with osteogenesis imperfecta. Bone. 2010;47:S410.

Oliveira TP, et al. Evaluation of patients with osteogenesis imperfecta treated on a bone fragility outpatient clinic. Arch Osteoporos. 2012;7:S199–200.

Tabanfar L, Diagnostic dilemma: mild and moderate forms of osteogenesis imperfecta. 2015: digitalcommons.slc.edu.

Martin E, et al. Characteristics of the osteogenesis imperfecta registry population. J Investig Med. 2010;58(1):203–4.

McKiernan FE. Musculoskeletal manifestations of mild osteogenesis imperfecta in the adult. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(12):1698–702.

Dung VC, Armstrong K, Ngoc CT, Thao BP, Khanh NN, Trang NT, Hoan NT, Dat NP, Munns C. Effect of osteogenesis imperfecta on children and their families. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol. 2013;2013(1):1.

Celin MR, Kruger KM, Caudill A, Nagamani SC, Centers LC, Harris GF, Smith PA, Brittle Bone Disorders Consortium. A Multicenter study of intramedullary rodding in osteogenesis imperfecta. JBJS Open Access. 2020;5(3)

Tosi LL, et al. Assessing disease experience across the life span for individuals with osteogenesis imperfecta: challenges and opportunities for patient-reported outcomes (PROs) measurement: a pilot study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14(1):23.

Atta I, et al. Effect of intravenous pamidronate treatment in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2014;24(9):653–7.

Engelbert RHH, et al. Osteogenesis imperfecta in childhood: Impairment and disability - a follow-up study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80(8):896–903.

Feehan AG, et al. A comparative study of quality of life, functional and bone outcomes in osteogenesis imperfecta with bisphosphonate therapy initiated in childhood or adulthood. Bone. 2018;113:137–43.

Vanz AP, et al. Health-related quality of life of children and adolescents with osteogenesis imperfecta: a cross-sectional study using PedsQL™. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18(1):95.

Hald JD, et al. Health-related quality of life in adults with osteogenesis imperfecta. Calcif Tissue Int. 2017;101(5):473–8.

Munns CF, et al. Delayed osteotomy but not fracture healing in pediatric osteogenesis imperfecta patients receiving pamidronate. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(11):1779–86.

Lindahl K, et al. Decreased fracture rate, pharmacogenetics and BMD response in 79 Swedish children with osteogenesis imperfecta types I, III and IV treated with Pamidronate. Bone. 2016;87:11–8.

Hald JD, et al. Skeletal phenotypes in adult patients with osteogenesis imperfecta-correlations with COL1A1/COL1A2 genotype and collagen structure. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27(11):3331–41.

Li LJ, et al. Genotype-phenotype relationship in a large cohort of osteogenesis imperfecta patients with COL1A1 mutations revealed by a new scoring system. Chin Med J (Engl). 2019;132(2):145–53.

Zhytnik L, et al. COL1A1/2 pathogenic variants and phenotype characteristics in ukrainian osteogenesis imperfecta patients. Front Genet. 2019;10:722.

Greeley CS, et al. Fractures at diagnosis in infants and children with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Pediatr Orthop. 2013;33(1):32–6.

Trejo P, et al. Diaphyseal femur fractures in osteogenesis imperfecta: characteristics and relationship with bisphosphonate treatment. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32(5):1034–9.

Koumakis E, Dellal A, Debernardi M, Cortet B, Debiais F, Javier RM, Thomas T, Mehsen-Cetre N, Cohen-Solal M, Fontanges E, Laroche M. Osteogenesis imperfecta: fracture characteristics during pregnancy and post-partum. Bone Reports. 2020;13:100319.

Folkestad L, et al. Fracture rates and fracture sites in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta: a nationwide register-based cohort study. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32(1):125–34.

Ohata Y, et al. Comprehensive genetic analyses using targeted next-generation sequencing and genotype-phenotype correlations in 53 Japanese patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. Osteoporos Int. 2019;30(11):2333–42.

Lin HY, et al. Genotype and phenotype analysis of Taiwanese patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:152.

Patel RM, et al. A cross-sectional multicenter study of osteogenesis imperfecta in North America - results from the linked clinical research centers. Clin Genet. 2015;87(2):133–40.

Scheres LJJ, et al. Adults with osteogenesis imperfecta: Clinical characteristics of 151 patients with a focus on bisphosphonate use and bone density measurements. Bone Rep. 2018;8:168–72.

Wekre LL, Eriksen EF, Falch JA. Bone mass, bone markers and prevalence of fractures in adults with osteogenesis imperfecta. Arch Osteoporos. 2011;6(1–2):31–8.

Al Agha A, et al. Vitamin d status in children and adolescents with osteogenesis imperfecta. Osteoporos Int. 2015;26(2):S457–8.

Kallur A, et al. To asses the incidence of low vitamin D levels in children with osteogenesis imperfecta and to determine its effect on bone healing and number of fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:S137.

Lindahl K, Rubin CJ, Åström E, Malmgren B, Kindmark A, Ljunggren Ö. Genotype–phenotype correlations and pharmacogenetic studies in 140 Swedish families with osteogenesis imperfecta. Bone. 2012;50(1):1.

Zambrano MB, et al. Study of the determinants of vitamin d status in pediatric patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Am Coll Nutr. 2016;35(4):339–45.

Bains JS, et al. A multicenter observational cohort study to evaluate the effects of bisphosphonate exposure on bone mineral density and other health outcomes in osteogenesis imperfecta. JBMR Plus. 2019;3(5): e10118.

Rauch F, et al. Bone mass, size, and density in children and adolescents with osteogenesis imperfecta: effect of intravenous pamidronate therapy. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18(4):610–4.

Ben Amor IM, et al. Skeletal clinical characteristics of osteogenesis imperfecta caused by haploinsufficiency mutations in COL1A1. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(9):2001–7.

Cheung MS, et al. Cranial base abnormalities in osteogenesis imperfecta: phenotypic and genotypic determinants. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(2):405–13.

Rauch F, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations in nonlethal osteogenesis imperfecta caused by mutations in the helical domain of collagen type I. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18(6):642–7.

de Lima MV, et al. Roentgenographic evaluation of the spine in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(47): e1841.

To MKT, Scoliosis in osteogenesis imperfecta a single centre cross sectional study. Combined Meeting of Asia Pacific Spine Society and …. 2019.

Zhytnik L, et al, Rib cage anomalies in a cohort of osteogenesis imperfecta patients. 9th International …, 2019.

Anissipour AK, et al. Behavior of scoliosis during growth in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(3):237–43.

Maioli M, et al. Genotype–phenotype correlation study in 364 osteogenesis imperfecta Italian patients. Eur J Hum Genet. 2019;27(7):1090–100.

Graff K, et al. Spatio-temporal parameters and body of gait and body deformations in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. Gait Posture. 2020;81:113–4.

Ahn J, et al. Acetabular protrusio in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta: risk factors and progression. J Pediatr Orthop. 2019;39(10):e750–4.

Radunovic Z, Wekre LL, Steine K. Right ventricular and pulmonary arterial dimensions in adults with osteogenesis imperfecta. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109(12):1807–13.

Wekre LL, et al. Spinal deformities and lung function in adults with osteogenesis imperfecta. Clin Respir J. 2014;8(4):437–43.

Aarabi M, et al. High prevalence of coxa vara in patients with severe osteogenesis imperfecta. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26(1):24–8.

Violas P, et al. Acetabular protrusion in osteogenesis imperfecta. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22(5):622–5.

Fassier AM, et al. Radial head dislocation and subluxation in osteogenesis imperfecta. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(12):2694–704.

Tam A, et al. A multicenter study to evaluate pulmonary function in osteogenesis imperfecta. Clin Genet. 2018;94(6):502–11.

Janus GJ, et al. Osteogenesis imperfecta in childhood: MR imaging of basilar impression. Eur J Radiol. 2003;47(1):19–24.

Kovero O, et al. Skull base abnormalities in osteogenesis imperfecta: a cephalometric evaluation of 54 patients and 108 control volunteers. J Neurosurg. 2006;105(3):361–70.

Ashwin C, et al. Learning effect on perinatal post-mortem magnetic resonance imaging reporting: single reporter diagnostic accuracy of 200 cases. Prenat Diagn. 2017;37(6):566–74.

Yonko EA, et al. Respiratory impairment impacts QOL in osteogenesis imperfecta independent of skeletal abnormalities. Arch Osteoporos. 2020;15(1):153.

Amako M, et al. Functional analysis of upper limb deformities in osteogenesis imperfecta. J Pediatr Orthop. 2004;24(6):689–94.

Brizola E, et al. Clinical features and pattern of fractures at the time of diagnosis of osteogenesis imperfecta in children. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2017;35(2):171–7.

Arponen H, et al. Prevalence and natural course of craniocervical junction anomalies during growth in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(5):1142–9.

Rusinska A, et al. Clinical heterogeneity of osteogenesis imperfecta: diagnostic difficulties on the basis of our own experience. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(1):S297.

DeVile C, et al. Management of scoliosis in children with severe, complex and atypical osteogenesis imperfecta. Arch Dis Child. 2019;104:A49.

Chagas CE, et al. Do patients with osteogenesis imperfecta need individualized nutritional support? Nutrition. 2012;28(2):138–42.

Arponen H, Changes in cranial base and craniocervical junction during growth in healthy individuals and in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. 2012: helda.helsinki.fi.

Wadanamby S, D Connolly, and P Arundel, Monitoring skull base abnormalities in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. 9th International …, 2019.

Semler O, et al. Wormian bones in osteogenesis imperfecta: Correlation to clinical findings and genotype. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152(7):1681–7.

Sato A, et al. Scoliosis in osteogenesis imperfecta caused by COL1A1/COL1A2 mutations - genotype-phenotype correlations and effect of bisphosphonate treatment. Bone. 2016;86:53–7.

McAllion SJ, Paterson CR. Musculo-skeletal problems associated with pregnancy in women with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;22(2):169–72.

Song Y, et al. Health-related quality of life in children with osteogenesis imperfecta: a large-sample study. Osteoporos Int. 2019;30(2):461–8.

Engelbert RH, et al. Osteogenesis imperfecta in childhood: impairment and disability. Pediatrics. 1997;99(2):E3.

Kok DHJ, et al. Bone mineral density in developing children with osteogenesis imperfecta. Acta Orthop. 2013;84(4):431–6.

Aglan MS, et al. Anthropometric measurements in Egyptian patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158(11):2714–8.

Castro LC, et al. Overweight and obesity in children and adolescents with moderate and severe forms of osteogenesis imperfecta. Hormone Res Paediatrics. 2017;88:259–60.

Germain-Lee EL, et al. Cross-sectional and longitudinal growth patterns in osteogenesis imperfecta: implications for clinical care. Pediatr Res. 2016;79(3):489–95.

Jensen BL, Lund AM. Osteogenesis imperfecta: clinical, cephalometric, and biochemical investigations of OI types I, III, and IV. J Craniofac Genet Dev Biol. 1997;17(3):121–32.

Radunovic Z, et al. Cardiovascular abnormalities in adults with osteogenesis imperfecta. Am Heart J. 2011;161(3):523–9.

Veilleux LN, et al. Muscle anatomy and dynamic muscle function in osteogenesis imperfecta type I. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(2):E356–62.

Barber LA, et al. Longitudinal growth curves for children with classical osteogenesis imperfecta (types III and IV) caused by structural pathogenic variants in type I collagen. Genet Med. 2019;21(5):1233–9.

Graff K, Syczewska M. Developmental charts for children with osteogenesis imperfecta, type I (body height, body weight and BMI). Eur J Pediatr. 2017;176(3):311–6.

Jain M, et al. Growth characteristics in individuals with osteogenesis imperfecta in North America: results from a multicenter study. Genet Med. 2019;21(2):275–83.

Mata Caballero R, et al. Cardiovascular abnormalities in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta: Casecontrol study. European Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;17:61.

Palomo T, et al. Body composition in children and adolescents with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Pediatr. 2016;169:232–7.

Rodrigues TB, et al. No difference in the proportion of overweight and obesity among pediatric patients with osteogenesis imperfecta throughout a ten-year period. Hormone Res Paediatrics. 2019;92:43–4.

Semler O, et al. Short stature in osteogenesis imperfecta is not caused by deficiencies in IGF1 or IGF-BP3. Hormone Res Paediatr. 2015;84:348.

Gjørup H, J D Hald, and T Harsløf, Craniofacial morphology and dental occlusion in adults with osteogenesis imperfecta: a comparison according to severity of …. European …, 2017.

Kruger K M, A Caudill, and MR Celin, Mobility in osteogenesis imperfecta: a multicenter North American Study. Am J …. 2020: ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

Rauch D, et al. Assessment of longitudinal bone growth in osteogenesis imperfecta using metacarpophalangeal pattern profiles. Bone. 2020;140: 115547.

Rush ET, et al. Echocardiographic phenotype in osteogenesis imperfecta varies with disease severity. Heart. 2017;103(6):443–8.

Hernández Jiménez V, et al. Structural and functional changes in the heart of adult patients with osteogenesis imperfecta: Case-control study. Med Clin (Barc). 2018;151(10):397–9.

Pinheiro BS, et al. Echocardiographic study in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. Cardiol Young. 2020;30(10):1490–5.

Zambrano MB, et al. Anthropometry, nutritional status, and dietary intake in pediatric patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Am Coll Nutr. 2014;33(1):18–25.

Semler O, H Hoyer-Kuhn, and C Stark, Results of a specialized rehabilitation approach in osteogenesis imperfecta. 7th International …, 2015.

Arponen H, et al. Fatigue and disturbances of sleep in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta - a cross-sectional questionnaire study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19(1):3.

Montpetit K, Lafrance ME, Glorieux FH, Fassier F, Hamdy R, Rauch F. Predicting ambulatory function at skeletal maturity in children with moderate to severe osteogenesis imperfecta. European J Pediatr. 2021;180:233–9.

Waltimo-Sirén J, et al. Craniofacial features in osteogenesis imperfecta: a cephalometric study. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;133(2):142–50.

Kuurila K, et al. Hearing loss in finnish adults with osteogenesis imperfecta: a nationwide survey. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2002;111(10):939–46.

Lund A, et al. Dental manifestations of osteogenesis imperfecta and abnormalities of collagen I metabolism. J Craniofac Genet Dev Biol. 1998;18(1):30–7.

Ma M, et al. Caries prevalence and experience in individuals with osteogenesis imperfecta: a cross-sectional multicenter study. Spec Care Dentist. 2019;39(2):214–9.

Staun Larsen L, Thuesen KJ, Gjørup H, Hald JD, Væth M, Dalstra M, Haubek D. Reduced mesiodistal tooth dimension in individuals with osteogenesis imperfecta: a cross-sectional study. Acta Odontol Scand. 2021;79(4):262–7.

Thuesen KJ, et al. The dental perspective on osteogenesis imperfecta in a Danish adult population. BMC Oral Health. 2018;18(1):175.

Apolinário AC, et al. Dental panoramic indices and fractal dimension measurements in osteogenesis imperfecta children under pamidronate treatment. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2016;45(4):20150400.

Andersson K, et al. Mutations in COL1A1 and COL1A2 and dental aberrations in children and adolescents with osteogenesis imperfecta - a retrospective cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(5): e0176466.

Gjørup H, K H Bendixen, and J D Hald, Dental occlusion and temporomandibular disorders in adults with osteogenesis imperfecta. on Osteogenesis …, 2017.

Gjørup H, JD Hald, and M Schmidt, Dentinogenesis imperfecta in adults with osteogenesis imperfecta. … on Osteogenesis , 2014.

Nguyen MS, et al, Dental findings of persons with osteogenesis imperfecta in Vietnam. Stoma Edu …. 2020: pdfs.semanticscholar.org.

Okawa R, et al. Oral manifestations of Japanese patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. Pediatr Dent J. 2017;27(2):73–8.

Saeves R, et al. Oral findings in adults with osteogenesis imperfecta. Spec Care Dentist. 2009;29(2):102–8.

Malmgren B, Norgren S. Dental aberrations in children and adolescents with osteogenesis imperfecta. Acta Odontol Scand. 2002;60(2):65–71.

Najirad M, et al. Oral health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with osteogenesis imperfecta: cross-sectional study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018;13(1):187.

Najirad M, et al. Malocclusion traits and oral health-related quality of life in children with osteogenesis imperfecta: a cross-sectional study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2020;151(7):480-490.e2.

Bendixen KH, et al. Temporomandibular disorders and psychosocial status in osteogenesis imperfecta - a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2018;18(1):35.

Gjørup H, Beck-Nielsen SS, Hald JD, Haubek D. Oral health-related quality of life in X-linked hypophosphataemia and osteogenesis imperfecta. J Oral Rehabil. 2021;48(2):160–8.

Chetty M, et al. Dentinogenesis imperfecta in Osteogenesis imperfecta type XI in South Africa: a genotype-phenotype correlation. BDJ Open. 2019;5:4.

Petersen K, Wetzel WE. Recent findings in classification of osteogenesis imperfecta by means of existing dental symptoms. ASDC J Dent Child. 1998;65(5):305–9.

Malmgren B, et al. Tooth agenesis in osteogenesis imperfecta related to mutations in the collagen type I genes. Oral Dis. 2017;23(1):42–9.

Brizola E, Staub AL, Félix TM. Muscle strength, joint range of motion, and gait in children and adolescents with osteogenesis imperfecta. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2014;26(2):245–52.

Daly K, et al. The prognosis for walking in osteogenesis imperfecta. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78(3):477–80.

Tosi L, et al Information system (PROMIS) instruments allow documentation of important components of the disease experience among individuals with Osteogenesis Imperfecta. 8th International …, 2017.

Coêlho G, Luiz LC, Castro LC, David AC. Postural balance, handgrip strength and mobility in Brazilian children and adolescents with osteogenesis imperfecta. Jornal de Pediatria. 2021;2(97):315–20.

Feinstein E, J Shapiro, and AW Francis, Patient reported prevalence of eye disease in osteogenesis imperfecta. … & Visual Science, 2014.

Swinnen FK, et al. Audiologic phenotype of osteogenesis imperfecta: use in clinical differentiation. Otol Neurotol. 2012;33(2):115–22.

Machol K, et al. Hearing loss in individuals with osteogenesis imperfecta in North America: results from a multicenter study. Am J Med Genet A. 2020;182(4):697–704.

da Costa Otavio AC, et al. Osteogenesis imperfecta and hearing loss: an analysis of patients attended at a benchmark treatment center in southern Brazil. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;277(4):1005–12.

Pedersen U. Hearing loss and stapedectomy in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. Connect Tissue Res. 1995;31(4):S49-53.

Swinnen FK, et al. Osteogenesis Imperfecta: the audiological phenotype lacks correlation with the genotype. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011;6:88.

Radunovic Z, Steine K. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease and cardiac symptoms: left and right ventricular function in adults with osteogenesis imperfecta. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31(11):1386–92.

Li L, et al. Aortic vascular properties in pediatric osteogenesis imperfecta: a two-dimensional echocardiography derived aortic strain study. European Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16:98.

Alaei M, Mosallanejad A, Fallah S, Shakiba M, Saneifard H, Alaei F, Shiari R, Sobouti B. Echocardiographic findings in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. Caspian J Pediatr. 2019;5(1):329–33.

Folkestad L, et al. Cardiovascular disease in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta - a nationwide, register-based cohort study. Int J Cardiol. 2016;225:250–7.

Mata Caballero R, et al. Cardiovascular functional abnormalities in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. European Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;17:106.

Wu PC, Liu DH. Validation of osteoporosis simple tool to identify primary osteoporosis in Taiwan men. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28:S569.

Philip RK, Qadri S. Severe forms of osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) in infants and the role of respiratory syncitial virus (RSV) immunoprophylaxis with palivizumab. Archiv Disease Childhood. 2012;97:517–18.

Pasieka HB, et al. Decreased collagen quantity rather than quality is more predictive of cutaneous manifestations in osteogenesis imperfecta. J Investig Dermatol. 2014;134:S104.

Simoes VRF, et al. High prevalence of nephrolithiasis and hypercalciuria in women with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Bone Miner Res. 2018;33:299.

Salter L, Offiah AC, Bishop N. Elevated platelet counts in a cohort of children with moderate-severe osteogenesis imperfecta suggest that inflammation is present. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103(8):767–71.

Glorieux FH, Rauch F. Muscle function in osteogenesis imperfecta type IV. J Bone Mineral Res. 2015;30:2150.

Paterson CR, Ogston SA, Henry RM. Life expectancy in osteogenesis imperfecta. BMJ. 1996;312(7027):351.

Singer RB, Ogston SA, Paterson CR. Mortality in various types of osteogenesis imperfecta. J Insur Med. 2001;33(3):216–20.

Michalus I, Z Nowicka, and W Pietras Anemia-novel clinically significant finding during intravenous pamidronate therapy of children diagnosed with osteogenesis imperfecta. 9th International …, 2019.

Goeller J K, et al. Perioperative management of pediatric patients with osteogenesis imperfecta undergoing orthopedic procedures. Current Anesthesiology …, 2017.

Hill C, et al. Sleep-related problems in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. 2019: bmjopenrespres.bmj.com.

Cubert R, et al. Osteogenesis imperfecta: mode of delivery and neonatal outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(1):66–9.

Liu Y, et al. Gene mutation spectrum and genotype-phenotype correlation in a cohort of Chinese osteogenesis imperfecta patients revealed by targeted next generation sequencing. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28(10):2985–95.

Vyskocil V, Pavelka T. Differential diagnosis of connective tissue disorders, marfan ehlers-danlos syndrome, osteogeneosis imperfecta and benign joint hyperelasticity. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(1):S06.

Youngblom E, Murray ML, Byers PH. Current practices and the provider perspectives on inconclusive genetic test results for osteogenesis imperfecta in children with unexplained fractures: elsi implications. J Law Med Ethics. 2016;44(3):514–9.

Ruck J, et al. Fassier-Duval femoral rodding in children with osteogenesis imperfecta receiving bisphosphonates: functional outcomes at one year. J Child Orthop. 2011;5(3):217–24.

Bianchi ML, et al. Bone health in children and adolescents with chronic diseases that may affect the skeleton: the 2013 ISCD pediatric official positions. J Clin Densitom. 2014;17(2):281–94.

Byers PH, et al. Genetic evaluation of suspected osteogenesis imperfecta (OI). Genet Med. 2006;8(6):383–8.

Cianferotti L, Brandi ML. Guidance for the diagnosis, prevention and therapy of osteoporosis in Italy. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2012;9(3):170–8.

Galindo-Zavala R, et al. Expert panel consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of secondary osteoporosis in children. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2020;18(1):20.

Mueller B, et al. Consensus statement on physical rehabilitation in children and adolescents with osteogenesis imperfecta. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018;13(1):158.

Rossini M, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis, prevention and management of osteoporosis. Reumatismo. 2016;68(1):1–39.

Ruggiero SL, et al. American association of oral and maxillofacial surgeons position paper on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws-2009 update. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67(5 SUPPL.):2–12.

Shapiro JR, Germain-Lee EL. Osteogenesis imperfecta: effecting the transition from adolescent to adult medical care. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2012;12(1):24–7.

Simm PJ, et al. Consensus guidelines on the use of bisphosphonate therapy in children and adolescents. J Paediatr Child Health. 2018;54(3):223–33.

van Brussel M, et al. The Utrecht approach to exercise in chronic childhood conditions: the decade in review. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2011;23(1):2–14.

van Dijk FS, et al. EMQN best practice guidelines for the laboratory diagnosis of osteogenesis imperfecta. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20(1):11–9.

White KK, et al. Best practice guidelines for management of spinal disorders in skeletal dysplasia. Orphanet J Rare Diseases. 2020;15:1.

Gooijer K, Harsevoort AG, van Dijk FS, Withaar H, Janus GJ, Franken AA. A baseline measurement of quality of life in 322 adults with osteogenesis imperfecta. JBMR plus. 2020;4(12):e10416.

Orlando G, Pinedo-Villanueva R, Reeves ND, Javaid MK, Ireland A. Physical function in UK adults with osteogenesis imperfecta: a cross-sectional analysis of the RUDY study. Osteoporosis Int. 2021;32:157–64.

Folkestad L, Hald JD, Hansen S, Gram J, Langdahl B, Abrahamsen B, Brixen K. Bone geometry, density, and microarchitecture in the distal radius and tibia in adults with osteogenesis imperfecta type I assessed by high-resolution pQCT. J Bone Mineral Res. 2012;27(6):1405–12.

Matsushita M, et al. Impact of fracture characteristics and disease-specific complications on health-related quality of life in osteogenesis imperfecta. J Bone Miner Metab. 2020;38(1):109–16.

Widmann RF, et al. Quality of life in osteogenesis imperfecta. Int Orthop. 2002;26(1):3–6.

Bronheim R, Khan S, Carter E, Sandhaus RA, Raggio C. Scoliosis and cardiopulmonary outcomes in osteogenesis imperfecta patients. Spine. 2019;44(15):1057–63.

Balkefors V, et al. Functioning and quality of life in adults with mild-to-moderate osteogenesis imperfecta. Physiother Res Int. 2013;18(4):203–11.

Khan SI, et al. Cardiopulmonary status in adults with osteogenesis imperfecta: intrinsic lung disease may contribute more than scoliosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020;478(12):2833–43.

Widmann RF, Bitan FD, Laplaza FJ, Burke SW, DiMaio MF, Schneider R. Spinal deformity, pulmonary compromise, and quality of life in osteogenesis imperfecta. Spine. 1999;24(16):1673.

Nicolaou N, et al. Use of the Sheffield telescopic intramedullary rod system for the management of osteogenesis imperfecta: clinical outcomes at an average follow-up of nineteen years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(21):1994–2000.

Rodríguez Celin, M. and V. Fano, Osteogenesis imperfecta: Level of independence and of social, recreational and sports participation among adolescents and youth. Arch Argent Pediatr, 2016. 114(3): p 248–51.

Montpetit K, et al. Activities and participation in young adults with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2011;4(1):13–22.

Arponen H, et al. Is sleep apnea underdiagnosed in adult patients with osteogenesis imperfecta? -a single-center cross-sectional study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018;13(1):231.

Moshkovich O, et al. Development of the OIQoL-A: a health-related quality of life measure for adults with osteogenisis imperfecta. Value in Health. 2017;20(9):A538.

Paiva, DFd, Perceptions of people with osteogenesis imperfecta about the interventions of the occupational therapy and its possibilities of care. Brazilian Journal of …, 2018.

Chevrel G, et al. Effects of oral alendronate on BMD in adult patients with osteogenesis imperfecta: a 3-year randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(2):300–6.

Harsevoort AGJ, et al. Fatigue in adults with Osteogenesis Imperfecta. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21(1):6.

Ablon J. Personality and stereotype in osteogenesis imperfecta: behavioral phenotype or response to life’s hard challenges? Am J Med Genetics Part A. 2003;122(3):201–14.

Seikaly MG, et al. Impact of alendronate on quality of life in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25(6):786–91.

Engelbert RHH, et al. Functional outcome in osteogenesis imperfecta: disability profiles using the PEDI. Pediatr Phys Ther. 1997;9(1):18–22.

Engelbert RH, Uiterwaal CS, Gerver WJ, van der Net JJ, Pruijs HE, Helders PJ. Osteogenesis imperfecta in childhood: impairment and disability. A prospective study with 4-year follow-up. Archiv Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(5):772–8.

Engelbert RH, et al. Osteogenesis imperfecta in childhood: perceived competence in relation to impairment and disability. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(7):943–8.

Luiz L and G Coelho, Handgrip strength as functionality and independence indicative in Osteogenesis Imperfecta. 9th international conference on children, 2019.

Tolboom N, et al. Osteogenesis imperfecta in childhood: effects of spondylodesis on functional ability, ambulation and perceived competence. Eur Spine J. 2004;13(2):108–13.

Rauch F, et al. Pamidronate in children and adolescents with osteogenesis imperfecta: effect of treatment discontinuation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(4):1268–74.

Ashby E, et al. Functional outcome of forearm rodding in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Pediatr Orthop. 2018;38(1):54–9.

Löwing K, et al. Effect of intravenous pamidronate therapy on everyday activities in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96(8):1180–3.

Murali CN, et al. Pediatric outcomes data collection instrument is a useful patient-reported outcome measure for physical function in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. Genet Med. 2020;22(3):581–9.

Graf A, et al. Gait characteristics and functional assessment of children with type I osteogenesis imperfecta. J Orthop Res. 2009;27(9):1182–90.

Caudill A, et al. Ankle strength and functional limitations in children and adolescents with type I osteogenesis imperfecta. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2010;22(3):288–95.

Huang RP, et al. Functional significance of bone density measurements in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(6):1324–30.

Kok DH, et al. Quality of life in children with osteogenesis imperfecta treated with oral bisphosphonates (Olpadronate): a 2-year randomized placebo-controlled trial. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166(11):1155–61.

Elona TS, Mentari M, Pulungan AB. “Correlation between frequency of bone fracture and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in children with osteogenesis imperfect”. Abstracts from the 9th Biennial Scientific Meeting of the Asia Pacific Paediatric Endocrine Society (APPES) and the 50th Annual Meeting of the Japanese Society for Pediatric Endocrinology (JSPE). Int J Pediatr Endocrinol. 2017;(Suppl 1):15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13633-017-0054-x.

Tsimicalis A, et al. Pain and quality of life of children and adolescents with osteogenesis imperfecta over a bisphosphonate treatment cycle. Eur J Pediatr. 2018;177(6):891–902.

Raimann A, et al Health-related quality of life in paediatric patients with Osteogenesis imperfecta. Bone Reports. 2020: Elsevier.

Garganta MD, et al. Cyclic bisphosphonate therapy reduces pain and improves physical functioning in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19(1):344.

Rochmah N, Faizi M. Pediatric quality of life inventory in children with osteogenesis imperfect in Dr soetomo hospital surabaya. Hormone Res Paediatr. 2018;90:181.

Lazow MA, et al. Stress, depression, and quality of life among caregivers of children with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Pediatr Health Care. 2019;33(4):437–45.

Nguyen, T.H., et al., Study of functional independence of patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. Annals Trans Med, 2017. 5(S2): p AB107-AB107.