Abstract

Background

Degenerative cervical myelopathy (DCM) is caused by degenerative or congenital changes to the discs and soft tissues of the cervical spine, which leads to chronic compression of the spinal cord. The current treatment for moderate to severe DCM consists of surgical decompression, which, while effective in most cases, can result in neuroinflammation and spinal cord reperfusion injury, leading to perioperative neurological complications and suboptimal neurological recovery. The primary objective of this study was to assess, in a translationally relevant animal model of DCM, the efficacy of perioperative methylprednisolone (MP) in enhancing neurological recovery and to evaluate its effect on the inflammatory response following decompression.

Methods

DCM was induced in C57BL/6 mice. Briefly, an aromatic polyether material was implanted underneath the C5-C6 laminae to cause progressive compression of the cervical spinal cord due to focal ossification. Decompressive surgery was undertaken at 12 weeks post initial biomaterial implantation. Animals received one dose of MP (30 mg/kg) or vehicle 30 min before decompression and at 2 weeks after decompression. Acute analysis of secreted cytokines and spinal cord microvasculature was complemented with immunohistochemistry for glial and neuronal cell markers. Locomotor outcomes were measured using the CatWalk system. The composition of circulating white blood cells was analyzed by flow cytometry.

Results

A single dose of MP before decompression significantly sped locomotor recovery (*p < 0.05) and reduced the incidence of perioperative motor complications, without affecting the composition of circulating white blood cells. Histological assessment of the spinal cord showed significant neuronal preservation and a modest reduction in parenchymal inflammation.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that MP reduces perioperative neurological complications following decompressive surgery for DCM by protecting neurons from inflammation, without compromising the composition of circulating immune cells. We propose that MP, which is commonly used for neurological disorders including spinal cord injury, be considered as a perioperative adjunct to decompressive surgery to attenuate neurological complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Degenerative cervical myelopathy (DCM) is an overarching term used to describe the most common forms of non-traumatic cervical spinal cord myelopathy (including cervical spondylotic myelopathy and ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament). DCM, which increases in prevalence with aging, is caused by degenerative or congenital changes to the discs and soft tissues of the cervical spine, which leads to chronic compression of the spinal cord [1]. Importantly, increased recruitment and excessive activation of different immune cells (activated microglia/macrophages, T cells and neutrophils), accompanied by the production of inflammatory cytokines in the spinal cord, have been shown to contribute to the progression of DCM [2, 3].

DCM is associated with significant neurological dysfunction, including gait impairment, loss of manual dexterity, and pain [1]. The current treatment, particularly with moderate to severe impairment [4], consists of surgical decompression [5]. However, approximately 4% of patients who undergo decompression develop perioperative neurological complications, including worsening of myelopathy and delayed C5 palsy [5]. Moreover, while most patients show neurological recovery with decompressive surgery, approximately 20% of patients fail to show neurological improvement, with a minority exhibiting continued neurological decline. Additionally, our DCM mouse model has demonstrated that post-decompression neurological decline is associated with the presence of an ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) and increased activation of the immune system [6, 7]. Thus, neuroprotective or neuroregenerative strategies, which complement surgical decompression and rehabilitation approaches, would enhance the management of patients with DCM.

In the present study, we hypothesized that reducing neuroinflammation following decompression for DCM would attenuate perioperative neurological decline and promote enhanced neural recovery. To examine this hypothesis, we used a mouse model of DCM that is associated with severe neuroinflammation [7]. This model is intended to mimic patients who present with chronically progressive DCM. The anti-inflammatory treatment selected for this study was methylprednisolone (MP), which has long-standing use in clinical practice as an anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective treatment for traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI) [8]. Patients with cervical SCI and low baseline severity of injury have been shown to benefit the most from MP treatment [9]; however, the use of MP for SCI has been questioned by some clinicians due to heterogeneous findings reported in the literature [10]. In animal models of SCI, MP has also been shown to preserve neurons and limit axonal dieback, as well as reduce microglia/macrophages and cytokine levels immediately following injury [11]. In addition to its use in SCI, the use of perioperative corticosteroids as a complementary approach to decompressive surgery has been shown to reduce pain as well as the duration of postoperative hospitalization in patients with lumbar and cervical radiculopathy due to degenerative conditions [12, 13]. Given this background, we sought to examine the repurposing of MP as a potential neuroprotective treatment for DCM as a complement to surgical decompression.

In the present study, we examined the effectiveness of MP treatment to reduce inflammation following decompression in a mouse model of DCM at the C5-C6 level. We observed perioperative MP treatment accelerated locomotor recovery by preserving the number of neurons, while modest effects on inflammation were observed. There was also a reduction in the incidence of perioperative motor complications (defined as reduced ankle movement and plantar stepping, forepaw palsy, and upper/lower limb stiffness and/or weakness) following MP treatment. Importantly, no harmful side effects (including increased incidence of wound infection and death) or changes in the peripheral white blood cell composition were observed after MP treatment.

Methods

Animals

The Animal Use Committee at the University Health Network (UHN; Toronto, Canada) approved the study protocol, and experiments were carried out in accordance with the committee recommendations. Adult 8-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the Ontario Council Institute (Canada) for use in this study. Investigators remained blinded to the treatment groups for the duration of the study.

Spinal cord compression and decompression

DCM was induced in mice as previously described [7]. Briefly, an aromatic polyether material was implanted underneath the C5-C6 laminae to cause chronic and progressive compression of the cervical spinal cord due to focal ossification. This compression model mimics ossification of the ligamentum flavum, one of the known causes of DCM [1]. At 12 weeks post-compression (i.e. post-material implantation), mice underwent decompression using a microdrill to remove the osteoid formation between the aromatic polyether and laminae. All surgical procedures were performed under anesthesia using 2% isoflurane. Following deep anesthesia with isoflurane, animals were sacrificed at 24 h, 2 weeks, or 5 weeks after surgical decompression.

Experimental groups

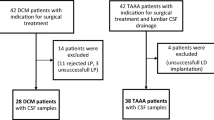

Animals were decompressed at 12 weeks following compression and randomly assigned to one of two experimental groups: (1) decompression with saline treatment (herein referred to as saline) and (2) decompression with MP treatment (30 mg/kg). MP treatment was given intravenously (i.v.) 30 min before surgical decompression and 2 weeks following decompression (Fig. 1). A second cohort of animals that did not undergo decompression (naive group) was used to assess the effect of decompression on the peripheral immune cell composition at 2 and 5 weeks following decompression.

Automated gait analysis

The CatWalk XT 10.6 system (Noldus, The Netherlands) was used to assess locomotion of DCM and decompressed animals, as described previously [7]. Stance phase, stride length, and swing speed were analyzed in both forepaws and hindlimbs at 2 and 5 weeks following decompression. Runs (2–3 per animal) were averaged and included in the analysis if they had a duration between 0.50 and 5 s, without significant differences in speed between runs [7, 14]. No food restriction or reward was used to motivate mice to perform the task.

Blood collection and flow cytometric analysis

Repeated blood sampling of mice was performed via saphenous vein puncture without anesthesia. Blood samples were collected using a 23G needle with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)-coated tubes to avoid blood coagulation [15] and were analyzed by flow cytometry [16]. Samples were collected at 12 weeks of DCM, and at 24 h, 2 weeks, and 5 weeks after decompression. Red blood cells where lysed in red blood cell lysis buffer [7] and washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cells were first stained with viability dye (Fixable viability dye eFluor 780, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 20 min, followed by extracellular staining with fluorescent antibodies to distinguish granulocytes, monocytes, and T cells in the blood. The antibodies used were as follows: Ly6C-Pacific blue (clone HK1.4; BioLegend), Ly6G-PerCP/Cy5.5 (clone 1A8; BioLegend), CD11b- FITC (clone M1/70; BioLegend), CD3-PE (clone 17A2; BioLegend), and CCR2-PE (clone 475301; R&D Systems). Matching isotype controls were used to set the gates during data acquisition and analysis. Data were acquired using a BD LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo X 10 (Trestar).

Luminex assay

Cervical spinal cord homogenates from a 0.3 cm long section of tissue centered at the compression area were prepared following transcardial perfusion with PBS, as previously described [7]. Levels of selected cytokines (IL-1α and β, TNF-α, IL-4, IL-10 and IL-6) were measured using a mouse cytokine array at 24 h after decompression (Eve Technologies, Calgary, AB, Canada).

Immunohistological analysis of the spinal cord

Animals were transcardially perfused with PBS, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. The spinal cords were dissected out (0.6 cm long section centered at the compression epicenter), post-fixed, and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose/PBS for 48 h. Coronal sections (30 μm thick) were prepared and blocked (10% non-fat milk, 1% BSA, 0.3% triton X-100 in PBS) for 1 h at room temperature (RT). Incubation with primary antibody was performed overnight (at 4 °C), followed by 1 h incubation with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 1:200) and the corresponding secondary antibody at RT. The following primary antibodies were used: NeuN conjugated to Alexa-Fluor 555 (1:250; clone A60, Millipore), Iba1 (1:300, Wako, 019-19741), GFAP-conjugated to Cy3 (1:300, Sigma-Aldrich, MAB3402C3), and Olig-2 (1:500; AB9610, Millipore Sigma). NeuN+ cells were automatically quantified over a 3240 μm area centered at the lesion epicenter in gray matter using the cell counter plug-in from ImageJ, whereas Iba1+ cells were manually counted in the dorsal and ventral horns. The area of the dorsal and ventral horns evaluated for GFAP immunoreactivity was traced using ImageJ software in a constant square region of 89 × 89 μm, as described before [7]. Olig-2 area in the gray matter was automatically quantified using a customized script and normalized to the area of DAPI staining, as a reproducible measure of Olig-2 cells accounting for background signal and overlapping cells. All images were acquired using either a × 10, × 20, or × 40 objective lens with a Nikon eclipse Ti C2+ inverted confocal microscope with the NIS element imaging software version 4.20.

In vivo power Doppler imaging

The spinal cord microvasculature was assessed with power Doppler imaging at 24 h and 2 weeks after surgical decompression, as previously described [17]. Static field of views (20 sagittal slices) that encompassed the entire lesion (130 × 90 px) were cropped from each sagittal stack and batch cropped in Photoshop CS6™. The resulting cropped images were then thresholded for the Doppler signal and batch-measured in ImageJ software using a customized script. The Doppler area of each sagittal slice was computed by taking the product of the total area of each image and the percent area of Doppler signal. The sum, termed the total Doppler area (TDA), was used to reflect the total functional vascularity of each sagittal stack.

Statistical analysis

The results were analyzed using Prism 5.0 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA) and SPSS version 22 (IBM, Armonck, NY, USA) software. Histology, Doppler, and Luminex results comparing two groups were analyzed using a t test. Flow cytometry and CatWalk results were analyzed using either a one or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post-hoc test. All data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Results were considered significant at a p value ≤ 0.05.

Results

Methylprednisolone mitigates perilesional spinal cord inflammation

We designed a randomized, blinded experiment where animals were divided into two groups that received two i.v injections of either MP or saline at two different time points, as shown in Fig. 1. We focused our assessments during the first 24 h and 2 weeks following decompression due to the development of IRI and high activation of the immune system observed in our animal model around these two time points [6, 7]. Although MP treatment has been shown to reduce inflammation after traumatic SCI [11], at 24 h after decompression in DCM the production of inflammatory cytokines (IL-1α, IL-1β, and TNF-α) was only modestly reduced in the MP group (n = 4), and only reached significance for IL-1α (Fig. 2a) compared to the saline treated group (n = 5). The expression of cytokines with anti-inflammatory (IL-4 and IL-10) and pleiotropic functions (IL-6) was not affected by MP treatment (Fig. 2a). Previous studies have demonstrated MP’s immunosuppressive effects by showing reduced macrophage/microglia proliferation following traumatic SCI [18]. For this reason, we quantified the number of Iba1+ cells in the spinal cord at 2 weeks after decompression. MP treatment slightly reduced the number of Iba1+ cells in the gray matter compared to the saline-treated group (n = 9 for both groups; paired t test, p = 0.14); however, this was not significant (Fig. 2b).

Methylprednisolone treatment diminishes acute cytokine production. a Expression of selected inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines was measured in the spinal cord at 24 h after decompression using a Luminex assay. Overall, MP treatment significantly decreased the levels of IL-1α (*p < 0.05). b Immunohistological analysis of the number of Iba1+ cells around the C5-C7 region at 2 weeks after decompression. Their number in the dorsal and ventral horns showed a non-significant reduction after MP treatment. Representative images for each treatment group are shown as well as a schematic of a spinal cord depicting the area analyzed. The white arrows indicate Iba1+ cells in the spinal cord. Data were analyzed using an unpaired Student’s t test and are presented as mean ± SEM

Glial cell recruitment is not altered by methylprednisolone treatment after decompression

The immunosuppressive effects of MP have been shown to alter GFAP expression following traumatic SCI [19]. However, at 2 weeks after decompression, MP treatment (n = 9) only slightly reduced astrogliosis in the gray matter compared to the saline-treated group (n = 9), but these differences were not significant (Fig. 3).

Astrogliosis is not significantly affected by MP treatment. GFAP immunoreactivity in the dorsal and ventral horns was analyzed around the C5-C7 region at 2 weeks after decompression. A non-significant reduction in GFAP immunoreactivity was observed after MP treatment. Representative images for each treatment group and a spine schematic depicting the area analyzed are shown. Data were analyzed using an unpaired Student’s t test and are presented as mean ± SEM. Scale bar = 25 μm. FOV, field of view

Early functional vascularity is not altered by methylprednisolone

Vascular compromise and neuroinflammation have been implicated in the progression of DCM [7, 20, 21]. To examine this, we measured functional vascularity using Power Doppler imaging at 24 h (saline n = 5; MP n = 4) and 2 weeks (n = 9 for both groups) after decompression. At both time points, no significant differences between MP and saline treated groups were observed (Fig. 4a, b). Interestingly, vascular function (at 2 weeks) showed increased recovery compared with the 24 h assessment for both MP and saline groups (Fig. 4a, b).

Methylprednisolone treatment does not affect functional vascularity. a, b Functional vascularity was measured using power Doppler at 24 h (a) and 2 weeks (b) after decompression. No significant changes were observed at any analyzed time points between the treatment groups. Data were analyzed using an unpaired Student’s t test and are presented as mean ± SEM

Reduced number of circulating white blood cells after decompression

Trauma or surgery can induce a stress response, which encompasses changes in both the endocrine and immune system [22, 23]. In order to characterize the changes in the circulating immune cells following surgery, we compared the composition of white blood cells in decompressed and age-matched naive animals at 2 and 5 weeks after decompression (Fig. 5a). At 2 weeks after decompression, there were no significant differences in monocytes, granulocytes, or T cell numbers (Fig. 5b–d). However, at 5 weeks after decompression, the number of all cell types was significantly reduced in decompressed animals (n = 8) compared to age-matched naive animals (n = 3–8) (Fig. 5b–d).

Peripheral white blood cell numbers decrease after decompression. a Scheme of the time points assessed for blood collection based on weeks after decompression (i), the bony formation between the material and laminae was removed at 12 weeks after implantation to achieve decompression (ii–iii), and summary of the experimental groups (iv). At 5 weeks after decompression, the number of all cell types (b–d) was significantly reduced (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01), without significant changes observed at 2 weeks. Data were analyzed by a two-way ANOVA and are presented as mean ± SEM of 3–4 independent experiments

Methylprednisolone does not compromise white blood cell composition

The immunosuppressive action of steroids, especially MP, has generated concern regarding the increased risk of infections, particularly when administered in conditions where the peripheral immune system is already suppressed, such as traumatic SCI [24, 25]. Since we did not find any signs of peripheral immune suppression following decompression, we hypothesized that systemic administration of MP early after decompression would not compromise the peripheral immune response. To examine this, we quantified the number of granulocytes, monocytes, and T cells before (n = 33) and after MP treatment with flow cytometry. At 24 h after decompression, the number of granulocytes and monocytes was not significantly altered by either decompression alone or between the MP and saline treatments (Fig. 6a, b). Further, the number of T cells was not altered by MP treatment compared with the saline-treated group. However, MP increased the number of T cells compared with levels before decompression (Fig. 6c, *p < 0.05). At 2 weeks after decompression, the number of granulocytes, monocytes and T cells was reduced compared with the 24-h assessment. Granulocytes and monocytes were slightly elevated in the MP-treated group compared with the saline group, without reaching significance (Fig. 6a, b). No significant changes were reported in any of the above white blood cell populations at 5 weeks after decompression (Fig. 6).

Methylprednisolone treatment does not affect the number of peripheral white blood cells. Blood samples were longitudinally collected at − 1 week, 24 h, 2 and 5 weeks after decompression and assessed by flow cytometry. The number of granulocytes (a), monocytes (b), and T cells (c) was not affected by MP treatment compared with the saline group. Representative flow charts for each cell type at 2 weeks after decompression are shown with quantification. Data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA and are presented as mean ± SEM

Methylprednisolone treatment leads to improvements in early locomotor outcomes after surgical decompression

Gait impairment is one of the first symptoms to present in patients with DCM [26]. We assessed changes in select forepaw and hindlimb gait parameters using the CatWalk system in DCM animals (n = 33) at 2 and 5 weeks after surgical decompression. One week before surgical decompression (pre-decompression baseline), no significant differences were observed in stance phase, swing speed, and stride length between DCM animals (data not shown). At 2 weeks after surgical decompression, we observed that animals treated with MP had a walking pattern similar to non-injured animals in contrast with the saline group that showed persistent deficits (Fig. 7a). Interestingly, MP treatment sped the temporal recovery of stride length as compared with the saline-treated group (Fig. 7b, *p < 0.05), but it did not affect stance phase (Fig. 7c) and swing speed (Fig. 7d). Nevertheless, the improvement in stride length did not persist at 5 weeks after decompression, where gait parameters reached similar values to the naive non-injured animals (n = 4) (Fig. 7b–d). These results suggest that the first dose of MP might have an early neuroprotective effect that enhances recovery of some locomotor parameters after decompression, without long-term effects. Of note, there was a reduction in the incidence of postoperative locomotor complications following decompression after MP treatment (Table 1). Specifically, at 24 h after surgery, 16.7% (3 out of 18) of the animals receiving the control treatment presented with motor complications (reduced ankle movement and plantar stepping and upper or lower extremity stiffness), whereas only 5.5% (1 out of 18) of animals treated with MP showed similar complications (p = 0.3).

Methylprednisolone treatment speeds recovery of gait. Locomotor recovery was quantified using the CatWalk system at 2 and 5 weeks after decompression. a Representative footprints of saline- and MP-treated animals at 2 weeks after decompression are shown. b Stride length in the forepaws was only significantly improved at 2 weeks after decompression, without significant changes at 5 weeks. No significant changes were observed in the hindlimbs (c–d). Stance phase and swing speed were not significantly affected in the forepaws and hindlimbs of the two treatment groups at any analyzed time point. Dotted line represents naive non-injured animals. Data were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA and are presented as mean ± SEM

Methylprednisolone treatment induces neuronal cell preservation

Chronic compression of the cervical spinal cord leads to a reduction in blood flow to the cord and thereby results in the loss of spinal cord motor neurons [6, 7, 27]. In order to assess neuronal preservation, we used the neuronal markers NeuN and Olig-2 to quantify the number of positive cells around the C5-C7 region using immunohistochemistry. Our results show MP significantly preserved the number of NeuN+ cells in the spinal cord compared with the saline-treated group at 2 weeks following decompression (n = 9 for both groups) (Fig. 8a). Furthermore, oligodendrocytes are known to undergo apoptosis during the progression of DCM [3], but are protected after MP treatment [28]. However, peri-operative treatment with MP did not alter the expression of oligodendrocytes compared with the saline-treated group at 2 weeks after decompression (Fig. 8b).

Methylprednisolone treatment promotes neuronal preservation in DCM. Immunohistochemical analysis of the decompressed spinal cord around the C5-C7 region. a Number of NeuN+ cells and representative images of the two treatment groups. NeuN+ cells were significantly increased compared with the saline-treated group at 2 weeks after decompression. b The percentage of Olig2+/DAPI+ area was not significantly different between the two treatment groups. Data were analyzed using an unpaired Student’s t test and are presented as mean ± SEM. Scale bars = 25 μm (a) and 500 μm (b). The arrows in a and b indicate a positive cell for each staining. FOV, field of view

Discussion

In this study, we showed that perioperative MP treatment following decompressive surgery for DCM accelerates locomotor recovery through enhanced neuronal preservation and reductions in inflammation, without compromising the composition of peripheral immune cells populations. Traumatic SCI has been shown to elicit systemic and parenchymal activation of the immune response that can contribute to organ dysfunction and post-injury complications [29] [25]. However, it is not known whether DCM, the most common form of non-traumatic SCI, has similar immune system activation. Therefore, we addressed the effectiveness of a combinatorial treatment paradigm to target delayed DCM decompression surgery. Previously, our lab has shown successful repurposing of the sodium-glutamate blocker Riluzole, an FDA-approved drug for the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, in mitigating ischemia-reperfusion injury in an experimental animal model of DCM [6]. This work was the foundation for the CSM-PROTECT clinical trial aimed at evaluating the efficacy of Riluzole in combination with decompression [30]. However, considering significant inflammation associated with delayed decompression, this study (for the first time) assessed the potential combinatorial use of the anti-inflammatory drug MP. Overall, MP treatment sped locomotor recovery and enhanced neuronal preservation, without compromising peripheral white blood cell composition.

Major surgical procedures can lead to alterations to the hemodynamic, endocrine, and immune functions of the body. Specifically, this leads to an initial activation of the peripheral immune system along with enhanced blood flow to muscle, liver, and ischemic organs [22]. These changes are followed by a phase of depressed immune function and recovery [31]. It is important to understand the duration of these phases following surgical decompression in order to determine the optimal time window and route (e.g., systemic or local) of administration for potential peri- and/or postoperative treatments that will enhance the effectiveness of decompression. In our DCM mouse model, excessive activation of the inflammatory response in the spinal cord has been associated with long-lasting symptoms and poor functional outcomes after decompression [7]. Interestingly, at 5 weeks after decompression in the present study, the number of white blood cells from the adaptive and innate immune system was significantly decreased. Although the systemic changes associated with decompression are different compared with other central nervous system (CNS) injury models, such as SCI, stroke, or multiple sclerosis (MS) [32,33,34,35,36]; a decreased number of T cell subsets has been reported as part of the normal response after major surgeries in patients [37]. In the context of traumatic SCI, mixed results associated with MP usage have led to significant controversy. When administered within the first 8 h after traumatic SCI, MP has been reported to improve neurological outcomes and short term motor scores [9, 38, 39]. However, aggregate evidence from different studies suggests a lack of effect in long-term motor recovery [39]. Despite evidence suggesting that steroids compromise the composition of the peripheral immune system in non-injured as well as injured conditions [24, 40,41,42], which raises concerns of possible negative side effects, the current guidelines for the management of acute SCI recommends MP treatment within the first 8 h of injury [8].

We have previously shown that there is an increased inflammatory response following delayed decompression for DCM, which can reduce the beneficial effects of surgical decompression [6, 7]. In the present study, MP administration resulted in, overall, small effects on the production of inflammatory cytokines, recruitment of Iba1+ cells and astrogliosis within the spinal cord. Albeit modest, these changes could lead to a more permissive environment that will allow neuronal preservation and an improved rate of functional recovery. This was reflected by an increased number of neurons in the MP-treated group, as compared to saline-treated animals. Similarly, in experimental models of traumatic SCI and ischemic optic neuropathy, MP treatment has been shown to preserve the number of neurons from apoptosis [43] and to reduce inflammation early after injury [11, 44]. Such regimens have been shown to accelerate the recovery of blood barrier integrity, reduce tissue damage, and attenuate recruitment of macrophages into the injured tissue [11, 44, 45]. MP may also be directly acting over neurons and their networks, potentially attenuating axonal excitability loss through the 5-HT1A receptor [46]. These receptors are key players of the locomotor network in vertebrates responsible for a regular locomotor pattern, whose function that can be inhibited by the production of nitric oxide [47]. Similarly, patients receiving corticosteroids for lumbar decompression or cervical radiculopathy have been shown to experience a shorter duration of postoperative hospitalization and pain [12] [13]. In our model, MP effects on the inflammatory response were modest and did not translate to long-term gait improvement. This could be partially explained by the short half life of MP [48] or the frequency of MP delivery. Future studies will need to address whether a repeated low-dose MP injection protocol will be able to induce long-term gait improvements and assess the effects of such a protocol on the peripheral immune response.

Our study has certain limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, although mouse models are commonly used in research, the composition of peripheral white blood cells between humans and mice is different. Human white blood cells are enriched in granulocytes and monocytes, whereas mouse white blood cells are rich in B and T cells [49]. Therefore, the inflammatory response following surgical decompression for DCM may differ between mice and humans. Secondly, DCM patients may have other co-morbidities, including cardiovascular disease and diabetes, which are not present in our animal model. Thus, the potential clinical translation of this work to DCM patients will need to control for other potential side effects of steroids.

Importantly, the incidence of motor complications was reduced after decompression with MP treatment. Given that 1 out of 3 (34.9%) [50] patients undergoing decompression for DCM can develop postoperative complications, which are not only neurological in nature, the use of complementary treatments for decompression, such as MP, that can reduce this incidence rate are encouraged.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the current study provides a deeper understanding of the peripheral immunological response following delayed decompression, and a detailed assessment of the role of MP in locomotor recovery following delayed surgical decompression. Larger studies, including prospective controlled trials in DCM patients, will be needed to better understand MP effects on the incidence of complications and enhancement of locomotor recovery, as well as the potential use of other anti-inflammatory drugs.

Abbreviations

- 5-HT1A :

-

5-Hidroxitriptamina 1A

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- DAPI:

-

4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DCM:

-

Degenerative cervical myelopathy

- EDTA:

-

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- GFAP:

-

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- Iba1:

-

Ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1

- IL-10:

-

Interleukin-10

- IL-1α:

-

Interleukin 1-alpha

- IL-1-β:

-

Interleukin 1-beta

- IL-4:

-

Interleukin-4

- IL-6:

-

Interleukin-6

- IRI:

-

Ischemia-reperfusion injury

- MP:

-

Methylprednisolone

- MS:

-

Multiple sclerosis

- NeuN:

-

Neuronal nuclear protein

- Olig-2:

-

Oligodendrocyte transcription factor 2

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PFA:

-

Paraformaldehyde

- SCI:

-

Spinal cord injury

- SEM:

-

Standard error of the mean

- TDA:

-

Total Doppler area

- TNF-α:

-

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha

References

Nouri A, Tetreault L, Singh A, Karadimas SK, Fehlings MG. Degenerative cervical myelopathy: epidemiology, genetics, and pathogenesis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015;40:E675–93.

Hirai T, Uchida K, Nakajima H, Guerrero AR, Takeura N, Watanabe S, Sugita D, Yoshida A, Johnson WE, Baba H. The prevalence and phenotype of activated microglia/macrophages within the spinal cord of the hyperostotic mouse (twy/twy) changes in response to chronic progressive spinal cord compression: implications for human cervical compressive myelopathy. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64528.

Yu WR, Liu T, Kiehl TR, Fehlings MG. Human neuropathological and animal model evidence supporting a role for Fas-mediated apoptosis and inflammation in cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Brain. 2011;134:1277–92.

Fehlings MG, Tetreault LA, Riew KD, Middleton JW, Aarabi B, Arnold PM, Brodke DS, Burns AS, Carette S, Chen R, et al. A clinical practice guideline for the management of patients with degenerative cervical myelopathy: recommendations for patients with mild, moderate, and severe disease and nonmyelopathic patients with evidence of cord compression. Global Spine J. 2017;7:70S–83S.

Fehlings MG, Tetreault LA, Kurpad S, Brodke DS, Wilson JR, Smith JS, Arnold PM, Brodt ED, Dettori JR. Change in functional impairment, disability, and quality of life following operative treatment for degenerative cervical myelopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Spine J. 2017;7:53S–69S.

Karadimas SK, Laliberte AM, Tetreault L, Chung YS, Arnold P, Foltz WD, Fehlings MG. Riluzole blocks perioperative ischemia-reperfusion injury and enhances postdecompression outcomes in cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:316ra194.

Vidal PM, Karadimas SK, Ulndreaj A, Laliberte AM, Tetreault L, Forner S, Wang J, Foltz WD, Fehlings MG. Delayed decompression exacerbates ischemia-reperfusion injury in cervical compressive myelopathy. JCI Insight. 2017;2(11). https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.92512. [Epub ahead of print].

Fehlings MG, Wilson JR, Tetreault LA, Aarabi B, Anderson P, Arnold PM, Brodke DS, Burns AS, Chiba K, Dettori JR, et al. A clinical practice guideline for the management of patients with acute spinal cord injury: recommendations on the use of methylprednisolone sodium succinate. Global Spine J. 2017;7:2013S–211S.

Evaniew N, Belley-Cote EP, Fallah N, Noonan VK, Rivers CS, Dvorak MF. Methylprednisolone for the treatment of patients with acute spinal cord injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurotrauma. 2016;33:468–81.

Fehlings MG, Wilson JR, Harrop JS, Kwon BK, Tetreault LA, Arnold PM, Singh JM, Hawryluk G, Dettori JR. Efficacy and safety of methylprednisolone sodium succinate in acute spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Global Spine J. 2017;7:116S–37S.

Tang P, Zhang Y, Chen C, Ji X, Ju F, Liu X, Gan WB, He Z, Zhang S, Li W, Zhang L. In vivo two-photon imaging of axonal dieback, blood flow, and calcium influx with methylprednisolone therapy after spinal cord injury. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9691.

Ghasemi M, Masaeli A, Rezvani M, Shaygannejad V, Golabchi K, Norouzi R. Oral prednisolone in the treatment of cervical radiculopathy: a randomized placebo controlled trial. J Res Med Sci. 2013;18:S43–6.

Aljabi Y, El-Shawarby A, Cawley DT, Aherne T. Effect of epidural methylprednisolone on post-operative pain and length of hospital stay in patients undergoing lumbar microdiscectomy. Surgeon. 2015;13:245–9.

Machado AS, Darmohray DM, Fayad J, Marques HG, Carey MR. A quantitative framework for whole-body coordination reveals specific deficits in freely walking ataxic mice. Elife. 2015;4. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.07892.

Hem A, Smith AJ, Solberg P. Saphenous vein puncture for blood sampling of the mouse, rat, hamster, gerbil, guinea pig, ferret and mink. Lab Anim. 1998;32:364–8.

Ulndreaj A, Tzekou A, Mothe AJ, Siddiqui AM, Dragas R, Tator CH, Torlakovic EE, Fehlings MG. Characterization of the antibody response after cervical spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34(6):1209-26. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2016.4498. [Epub 2016 Dec 21].

Badner A, Vawda R, Laliberte A, Hong J, Mikhail M, Jose A, Dragas R, Fehlings M. Early intravenous delivery of human brain stromal cells modulates systemic inflammation and leads to vasoprotection in traumatic spinal cord injury. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2016;5:991–1003.

Schroter A, Lustenberger RM, Obermair FJ, Thallmair M. High-dose corticosteroids after spinal cord injury reduce neural progenitor cell proliferation. Neuroscience. 2009;161:753–63.

Liu WL, Lee YH, Tsai SY, Hsu CY, Sun YY, Yang LY, Tsai SH, Yang WC. Methylprednisolone inhibits the expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein and chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans in reactivated astrocytes. Glia. 2008;56:1390–400.

Karadimas SK, Moon ES, Yu WR, Satkunendrarajah K, Kallitsis JK, Gatzounis G, Fehlings MG. A novel experimental model of cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM) to facilitate translational research. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;54:43–58.

Yu WR, Baptiste DC, Liu T, Odrobina E, Stanisz GJ, Fehlings MG. Molecular mechanisms of spinal cord dysfunction and cell death in the spinal hyperostotic mouse: implications for the pathophysiology of human cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;33:149–63.

Kohl BA, Deutschman CS. The inflammatory response to surgery and trauma. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2006;12:325–32.

Desborough JP. The stress response to trauma and surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85:109–17.

Ulndreaj A, Chio JC, Ahuja CS, Fehlings MG. Modulating the immune response in spinal cord injury. Expert Rev Neurother. 2016;16:1127–9.

Brommer B, Engel O, Kopp MA, Watzlawick R, Muller S, Pruss H, Chen Y, DeVivo MJ, Finkenstaedt FW, Dirnagl U, et al. Spinal cord injury-induced immune deficiency syndrome enhances infection susceptibility dependent on lesion level. Brain. 2016;139:692–707.

Malone A, Meldrum D, Bolger C. Gait impairment in cervical spondylotic myelopathy: comparison with age- and gender-matched healthy controls. Eur Spine J. 2012;21:2456–66.

Kurokawa R, Murata H, Ogino M, Ueki K, Kim P. Altered blood flow distribution in the rat spinal cord under chronic compression. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36:1006–9.

Xu J, Chen S, Chen H, Xiao Q, Hsu CY, Michael D, Bao J. STAT5 mediates antiapoptotic effects of methylprednisolone on oligodendrocytes. J Neurosci. 2009;29:2022–6.

Sun X, Jones ZB, Chen XM, Zhou L, So KF, Ren Y. Multiple organ dysfunction and systemic inflammation after spinal cord injury: a complex relationship. J Neuroinflammation. 2016;13:260.

Fehlings MG, Wilson JR, Karadimas SK, Arnold PM, Kopjar B. Clinical evaluation of a neuroprotective drug in patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy undergoing surgical treatment: design and rationale for the CSM-Protect trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013;38:S68–75.

Gaudilliere B, Fragiadakis GK, Bruggner RV, Nicolau M, Finck R, Tingle M, Silva J, Ganio EA, Yeh CG, Maloney WJ, et al. Clinical recovery from surgery correlates with single-cell immune signatures. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:255ra131.

Haeusler KG, Schmidt WU, Fohring F, Meisel C, Helms T, Jungehulsing GJ, Nolte CH, Schmolke K, Wegner B, Meisel A, et al. Cellular immunodepression preceding infectious complications after acute ischemic stroke in humans. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;25:50–8.

Prass K, Meisel C, Hoflich C, Braun J, Halle E, Wolf T, Ruscher K, Victorov IV, Priller J, Dirnagl U, et al. Stroke-induced immunodeficiency promotes spontaneous bacterial infections and is mediated by sympathetic activation reversal by poststroke T helper cell type 1-like immunostimulation. J Exp Med. 2003;198:725–36.

Riegger T, Conrad S, Schluesener HJ, Kaps HP, Badke A, Baron C, Gerstein J, Dietz K, Abdizahdeh M, Schwab JM. Immune depression syndrome following human spinal cord injury (SCI): a pilot study. Neuroscience. 2009;158:1194–9.

Meisel C, Schwab JM, Prass K, Meisel A, Dirnagl U. Central nervous system injury-induced immune deficiency syndrome. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:775–86.

Romme Christensen J, Bornsen L, Ratzer R, Piehl F, Khademi M, Olsson T, Sorensen PS, Sellebjerg F. Systemic inflammation in progressive multiple sclerosis involves follicular T-helper, Th17- and activated B-cells and correlates with progression. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57820.

Slade MS, Simmons RL, Yunis E, Greenberg LJ. Immunodepression after major surgery in normal patients. Surgery. 1975;78:363–72.

Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Collins WF, Holford TR, Young W, Baskin DS, Eisenberg HM, Flamm E, Leo-Summers L, Maroon J, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of methylprednisolone or naloxone in the treatment of acute spinal-cord injury. Results of the second national acute spinal cord injury study. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1405–11.

Evaniew N, Noonan VK, Fallah N, Kwon BK, Rivers CS, Ahn H, Bailey CS, Christie SD, Fourney DR, Hurlbert RJ, et al. Methylprednisolone for the treatment of patients with acute spinal cord injuries: a propensity score-matched cohort study from a Canadian multi-center spinal cord injury registry. J Neurotrauma. 2015;32:1674–83.

Pountain GD, Keogan MT, Hazleman BL, Brown DL. Effects of single dose compared with three days’ prednisolone treatment of healthy volunteers: contrasting effects on circulating lymphocyte subsets. J Clin Pathol. 1993;46:1089–92.

Martin-Vaquero P, da Costa RC, Allen MJ, Moore SA, Keirsey JK, Green KB. Proteomic analysis of cerebrospinal fluid in canine cervical spondylomyelopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015;40:601–12.

Aldrighetti L, Pulitano C, Arru M, Finazzi R, Catena M, Soldini L, Comotti L, Ferla G. Impact of preoperative steroids administration on ischemia-reperfusion injury and systemic responses in liver surgery: a prospective randomized study. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:941–9.

Li D, Wang G, Han D, Bi J, Li C, Wang H, Liu Z, Gao W, Gao K, Yao T, et al. MP resulting in autophagic cell death of microglia through zinc changes against spinal cord injury. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:6090316.

Huang TL, Wen YT, Chang CH, Chang SW, Lin KH, Tsai RK. Early methylprednisolone treatment can stabilize the blood-optic nerve barrier in a rat model of anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (rAION). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58:1628–36.

Takami T, Oudega M, Bethea JR, Wood PM, Kleitman N, Bunge MB. Methylprednisolone and interleukin-10 reduce gray matter damage in the contused Fischer rat thoracic spinal cord but do not improve functional outcome. J Neurotrauma. 2002;19:653–66.

Sasaki T, Sakuma J, Ichikawa T, Matsumoto M, Tiwari P, Young W, Kodama N. Effects of methylprednisolone on axonal depression induced by hypoxia, gamma-aminobutyric acid, and (+/−)-8-hydroxy-dipropylaminotetralin hydrobromide. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:1477–83. discussion 1483

Grillner S. The motor infrastructure: from ion channels to neuronal networks. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:573–86.

Uhl A, Czock D, Boehm BO, Zellner D, Mertz A, Keller F. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of methylprednisolone after one bolus dose compared with two dose fractions. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27:281–7.

Rongvaux A, Takizawa H, Strowig T, Willinger T, Eynon EE, Flavell RA, Manz MG. Human hemato-lymphoid system mice: current use and future potential for medicine. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31:635–74.

Fehlings MG, Kopjar B, Ibrahim A, Tetreault LA, Arnold PM, Defino H, Kale SS, Yoon ST, Barbagallo GM, Bartels RHM, et al. Geographic variations in clinical presentation and outcomes of decompressive surgery in patients with symptomatic degenerative cervical myelopathy: analysis of a prospective, international multicenter cohort study of 757 patients. Spine J. 2018;18(4):593–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2017.08.265. [Epub 2017 Sep 6].

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Sadiya Yousef, Maria Bisa, and Maria Monroy for their assistance with animal treatments. We would like to thank Tim Worden for assistance editing this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the 21st Century Research Grant from the Cervical Spine Research Society and the Krembil Research Institute postdoctoral fellowship (PMV). MGF is supported by the Gerry and Tootsie Halbert Chair in Neural Repair and Regeneration, the Krembil Foundation and DeZwirek Family Foundation.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MGF and PMV conceived the study and the experimental design. AU and PMV performed the sample collection and flow cytometry experiments. PMV performed the neurobehavioral tests, immunohistochemistry experiments, and some cell quantification and surgeries. AB performed the power Doppler imaging experiments and analysis. JH performed the analysis of Doppler images and cell quantification. All the authors contributed to writing the manuscript, as well as read and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The Animal Use Committee at the University Health Network (UHN; Toronto, Canada) approved the study protocol, and all experiments were carried out in accordance with the committee recommendations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Vidal, P.M., Ulndreaj, A., Badner, A. et al. Methylprednisolone treatment enhances early recovery following surgical decompression for degenerative cervical myelopathy without compromise to the systemic immune system. J Neuroinflammation 15, 222 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-018-1257-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-018-1257-7