Abstract

Objective

To synthesize current understanding of how community-based health worker (CHW) programs can best be designed and operated in health systems.

Methods

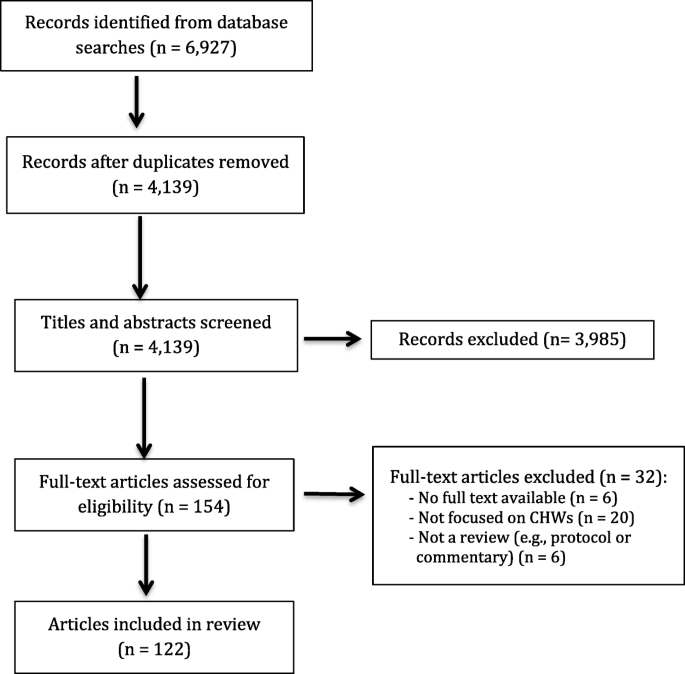

We searched 11 databases for review articles published between 1 January 2005 and 15 June 2017. Review articles on CHWs, defined as non-professional paid or volunteer health workers based in communities, with less than 2 years of training, were included. We assessed the methodological quality of the reviews according to AMSTAR criteria, and we report our findings based on PRISMA standards.

Findings

We identified 122 reviews (75 systematic reviews, of which 34 are meta-analyses, and 47 non-systematic reviews). Eighty-three of the included reviews were from low- and middle-income countries, 29 were from high-income countries, and 10 were global. CHW programs included in these reviews are diverse in interventions provided, selection and training of CHWs, supervision, remuneration, and integration into the health system. Features that enable positive CHW program outcomes include community embeddedness (whereby community members have a sense of ownership of the program and positive relationships with the CHW), supportive supervision, continuous education, and adequate logistical support and supplies. Effective integration of CHW programs into health systems can bolster program sustainability and credibility, clarify CHW roles, and foster collaboration between CHWs and higher-level health system actors. We found gaps in the review evidence, including on the rights and needs of CHWs, on effective approaches to training and supervision, on CHWs as community change agents, and on the influence of health system decentralization, social accountability, and governance.

Conclusion

Evidence concerning CHW program effectiveness can help policymakers identify a range of options to consider. However, this evidence needs to be contextualized and adapted in different contexts to inform policy and practice. Advancing the evidence base with context-specific elements will be vital to helping these programs achieve their full potential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Community-based health worker (CHW) programs are undergoing a resurgence, as these health workers are envisioned to be culturally adept members of comprehensive and people-centered primary health care teams that will enable universal health care [1]. The last decade has seen both the introduction as well as the re-invigoration of national CHW programs in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [2, 3]. These programs involve the delivery of community-based health services by paid or volunteer health workers with fewer than 2 years training. There is a rapid growth of evidence on the effectiveness of community-based interventions [4, 5], positive experiences with reinvigorated national CHW programs [2], and renewed interest in stronger national CHW programs [6]. Health systems in LMICs and high-income countries (HICs) are expanding their utilization of CHWs in order to meet population health needs, improve access to services, address health inequities, and improve health system performance and efficiency [7]. Policymakers need evidence-based guidance to further develop this cadre of the health workforce. As a first step in developing policy guidance on health policy and systems support to optimize CHW programs, the World Health Organization (WHO) commissioned a systematic review of available reviews related to CHWs.

This systematic review synthesizes existing reviews on CHWs in order to map what is known about these programs. We present evidence on the roles and capacities of CHWs as well as the health system enablers that can support their functionality. We reviewed heterogeneous evidence to identify the types of interventions that CHWs provide, as well as optimal approaches to training, support, supervision, and remuneration, and health system integration (i.e., recognition in national health care planning, regulation, and implementation) [8].

Methods

Search strategy

We searched for articles published between 1 January 2005 and 15 June 2017 in 11 electronic databases: PubMed, Embase, PASCAL Biomed, the Cochrane Library, Ovid’s Global Health, WHO Global Health Regional Libraries, the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Epistemonikos, Health Systems Evidence, PROSPERO, and the National Guideline Clearinghouse of the US Department of Health and Human Services. Searches were developed and conducted by an academic librarian (co-author MG) and peer reviewed by a second librarian prior to implementation.

The systematic literature search used a combination of controlled vocabulary and keywords for two concepts: (1) reviews and (2) community-based health workers (e.g., “community health worker”, “lay health worker”, “close-to-community provider”). We used the validated systematic review filter for PubMed [9] and expanded it to catch 30 key articles. Similarly for Embase, we used the validated Wilcynski and Haynes, “small drop in specificity, substantive gain in sensitivity” systematic review query [10] and expanded it with additional terms (metanalysis; review:ti), to include, for example, all titles with the word “review” in them. In the other nine databases, we did not use pre-developed review filters but instead used simpler search strings for the concept “review.” We did not limit to language. All titles and abstracts relevant to our study were retrieved and searched for full text. See Additional file 1 for the full PubMed search strategy.

Eligibility criteria, screening, and article selection

Articles were included if they were (a) reviews and (b) focused on CHWs. We included systematic reviews as well as non-systematic reviews (such as realist, narrative, scoping, and literature reviews), because many non-systematic reviews provided insight into CHW program design and health system integration. Our inclusive approach brought together reviews on CHWs that used a wide range of synthesis methods to comment on many features of CHW programs, going beyond the effectiveness focus of systematic meta-analysis. We defined CHWs as health workers based in communities (i.e., conducting outreach from their homes and beyond primary health care facilities or based at peripheral health posts that are not staffed by doctors or nurses), who are either paid or volunteer, who are not professionals, and who have fewer than 2 years training but at least some training, if only for a few hours. Adhering closely to this definition led us to include some programs, such as those for peer supporters and traditional birth attendants with some training, that reflect divergent and context-specific understandings of the term “CHW.” We excluded articles that did not directly mention CHWs or mentioned them only in passing without information on their role. Article titles and abstracts were divided and assigned for independent review to two authors from among KS, HBP, SWB, KDR, and GP, with a third author from among the same group selected on a revolving basis to resolve disputes. Full texts of retained articles underwent a final screening for eligibility.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Included articles were divided among KS, HBP, SWB, KDR, and GP for detailed data extraction. Data extractors used a pilot-tested framework (in Excel) that synthesized content on the following topics, adapted from the 2006 World Health Report’s framework on the working life of health care providers [11]: CHW roles and capacities, training, deployment, performance measurement, remuneration and incentives, support and supervision, cost effectiveness, community embeddedness, logistical support and supplies, and integration into health systems. KS spot-checked the data extraction by frequently returning to original articles for verification.

Two authors (SWB and MG) assessed the methodological quality of the systematic reviews using the 11-item validated Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) criteria [12]. They began by both rating the same 10 systematic reviews and then compared and discussed their ratings to obtain consensus on how to proceed. They then divided the remaining systematic reviews between them and rated a random sample of 10% in duplicate to check agreement. Disagreements were limited and resolved through discussion. For two AMSTAR items, we assessed the articles according to the original (strict) AMSTAR criteria and also for adapted (relaxed) criteria that we developed to more appropriately assess the quality of included systematic reviews. See Additional file 2 for an explanation of the ratings. The non-systematic reviews used a diverse range of non-systematic approaches to evidence synthesis across a wide array of research questions, making the application of a standardized quality criteria inappropriate.

Throughout this report, we use the term CHW although many review articles and individual studies used different terms such as close-to-community provider or trained traditional birth attendant.

Results

From 4 139 unique references identified in our search, 122 reviews met our inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Additional file 3 provides an overview of the included reviews, which can be searched and filtered for regional focus, review type (non-systematic, systematic, meta-analysis), population focus, health issue, nature of the intervention, findings on CHW capacities and/or intervention outcomes, and AMSTAR rating. Additional file 4 presents a summary of the main findings of all included articles. Additional file 5 presents complete references of included and excluded articles.

Of the 122 included reviews, 75 were systematic (including 34 meta-analyses) and were assessed using the AMSTAR quality criteria (Additional files 2 and 3). Seven of the 11 AMSTAR indicators of quality were met by the vast majority of the systematic reviews included in our study, while the remaining four AMSTAR quality indicators (duplicate data screening and data extraction, gray literature searched, publication bias discussed; and included and excluded studies listed) were less commonly met.

Most of the reviews focused on LMICs (n = 83) and a range of primary health care (n = 14), child health (n = 13), and maternal and child health (n = 14) interventions. High-income country reviews (n = 29) tended to focus on non-communicable diseases (n = 12) and reaching specific underserved groups (n = 7) (Table 1).

We now present findings from the reviews on considerations for CHW programmatic design and operation in health systems. We first present evidence on CHW functions and their contributions to improving health outcomes. We then report on health system enablers that can support CHW functionality, including optimal approaches to training, support, supervision, remuneration, and health system integration.

CHW roles and capacities

CHWs perform a variety of health system functions, which can be clustered into six general categories (Table 2).

The number, complexity, and range of functions CHWs perform vary substantially among programs according to context-specific needs and opportunities; functions also evolve over time [13]. While there is no optimal set of tasks or workload level that maximizes CHW productivity, one review [14] cited studies that found that too many responsibilities reduce CHW productivity and service quality, and CHWs in these situations are forced to choose which tasks to perform based on factors such as feasibility, remuneration, or preference. The authors of this review conclude that CHWs are more likely to succeed when they have a clear role and a limited number of tasks. In LMICs, CHWs commonly provide curative services, and there is some evidence that being tasked with curative tasks as opposed to solely providing health education or psychosocial support may increase CHW motivation in LMIC settings [15].

Among the reviews that assessed CHW contributions to addressing specific health issues, most found that CHWs can improve health outcomes (Table 3) but many noted concerns about the low quality of included studies and emphasized the importance of health systems enablers such as training and support, discussed in later sections of this article. The reviews were heterogeneous, examining diverse CHW programs and analyzing effectiveness across a range of health outcome measures. As a result, a meta-synthesis across the reviews was unfeasible. Thus, while Table 3 summarizes evidence on CHW contributions to health outcomes, we encourage readers to refer to each individual review in Additional file 3 and Additional file 4 for details.

As shown in Table 3, CHWs can make important contributions to improving health, particularly in extending care to underserved groups, and can successfully handle complex health counseling and biomedical tasks. However, CHWs can only meet their potential in performing these roles and improving health outcomes when supported by a range of health system enablers, discussed next.

Training

The proper amount and type of training required by CHWs must be understood in relation to the health system context, the CHWs’ pre-existing capacities, and the roles that CHWs are expected to play. Table 4 presents findings from the review literature on core considerations in CHW training domains.

Training should seek to impart both technical competency and socially oriented capacities such as skills in communication and counseling as well as awareness of the importance of confidentiality [15,16,17]. Awareness of the social and political determinants of health [18] and problem-solving skills were also identified as being important [19]. One review noted that theoretical, classroom-based competency-oriented CHW training to promote immunization in India is an inappropriate approach [20]. Other reviews suggest that some competencies such as record keeping or correctly interpreting malaria test results can be introduced in the classroom but require supportive supervision and hands-on practice to be implemented properly in the field [20, 21].

Training increases CHW knowledge and skills [22] and can positively influence CHW motivation, job satisfaction, and performance [23, 24]. However, there was no direct evidence linking training to health outcomes in one review that looked for it [25], nor is there evidence that different aspects of training or different training approaches affect CHW performance [24]. One pathway through which training can contribute to CHW motivation is by increasing community confidence in their CHWs and ultimately increasing CHWs’ confidence in their capacity to perform their duties [20, 24]. Relatedly, short and insufficient training erodes CHW confidence and reduces community trust and uptake of their CHW’s services [26].

Supervision

Supervision was often mentioned as critical for the effectiveness of CHWs, and there is some evidence regarding the benefits of supervision on CHW performance [14, 15, 23, 27, 28]. However, few details of the supervisory structure (type of supervisor, frequency of supervision, and type of training and support provided to supervisors) contributing to success were mentioned [15], and few studies have tested which approaches work best or how they are best implemented [15, 29,30,31]. Poor-quality supervision and low recognition from the health system can undermine community embeddedness and reduce CHW motivation [32,33,34]. Negative interactions of CHWs with higher-level health system actors (such as punitive supervision styles) can discourage and demotivate CHWs [33]. Supervision is often one of the “weakest links” in a CHW program, and CHW programs commonly give inadequate attention to ensuring high-quality supervision [14, 35], with negative implications for CHW empowerment [36]. Table 5 summarizes findings from the review literature on support and supervision.

Level of education prior to becoming a CHW

There is some evidence that CHWs with higher levels of formal education prior to becoming CHWs are more effective (for example, in record-keeping, diagnosing childhood illness, and appropriately counseling clients), but more highly educated CHWs may also be more likely to drop out after deployment [24]. One review concluded that completion of primary school should be a minimum educational requirement for entering CHW training to meet the needs of underserved communities far from health centers [35].

Performance measurement

The reviews included in our study provided very little evidence linking routine supervisory performance appraisal to CHW performance as measured by researchers [15]. However, formal supervisory checklists may increase the efficiency of identifying CHWs who are most in need of further training or supervision [20].

Logistical support and supplies

Regular provision of logistical support and supplies (such as drugs and educational materials) is essential to maintain CHW program effectiveness, productivity, and respect of CHWs by the community [26, 37]. Lack of supplies is demotivating for CHWs [14, 15, 35, 38]. Table 6 summarizes findings from the review literature on logistics and supplies.

Remuneration and incentives

Monetary remuneration (such as salaries, financial incentives, or income from selling commodities) and non-monetary incentives (such as respect, trust, recognition, and opportunities for personal growth, learning, and career advancement) are important motivators for CHWs [15, 19, 23, 33, 39]. In Kok et al.’s [15] review on intervention design factors that influence CHW performance, 25 of the 81 studies with information on incentives reported that CHWs were dissatisfied with their incentives. Satisfaction (or dissatisfaction) with incentives was closely linked to CHW motivation and performance (or lack thereof). Improved financial remuneration can reduce attrition among CHWs in LMICs [23, 40]. CHW rights and the need of CHWs for reliable financial remuneration were discussed in only one review, which highlighted Indian CHWs’ consistent (and unmet) demand for salaried positions [41]. Table 7 summarizes findings from the review literature on remuneration and incentives.

Deployment

There is no simple formula for determining the optimal size of a CHW’s catchment population. Instead, decisions about catchment area population should be based on a variety of context-specific considerations: frequency of contact required; nature of the services provided; expected weekly time commitment from the CHW; and local geography (including proximity of households), weather, and transport availability [14, 15, 24]. One review [42] found that for interventions consisting of home visits only, there was no consistent effect of the size of the catchment population and neonatal mortality impact. However, when the interventions involved community mobilization as well, the reduction in neonatal mortality was greater when the catchment population for the CHW was smaller. Another related finding was that a high workload can lead to CHW demotivation [23].

Community embeddedness

Fourteen reviews highlighted aspects of community embeddedness as important enablers of CHW program success [14, 15, 19, 23, 34, 35, 37, 40, 43,44,45,46,47,48]. CHWs are embedded in communities when community members trust and respect them and feel a sense of ownership over the program, such as can be achieved by giving communities a role in CHW selection and definition of CHW activities [19]. The community’s acceptance of CHWs and their sense that the CHW program is locally appropriate and “owned” is associated with CHW retention, motivation, performance, accountability, and support, and ultimately with the acceptability and uptake of CHWs’ health-related work [14, 15, 19, 23, 38, 40, 47, 49]. Locally trusted CHWs can serve as an effective link between health facilities, health workers, and communities [50], and CHWs who are embedded in their communities can provide services to difficult-to-reach populations [20, 40]. However, CHW embeddedness can lead to CHWs being caught in tensions between the community and the health system as well as between social and biomedical issues [51]. Table 8 summarizes findings from the review literature on community embeddedness.

Cost-effectiveness

Research from LMICs has found that shifting aspects of HIV care from higher-level health workers to CHWs is cost-effective [50, 52, 53]. There is some evidence of cost-effectiveness for community case management of malaria by CHWs compared to standard malaria treatment at a health facility [21, 33], for the provision of mental health care by CHWs in LMICs [54], and for the delivery of multiple primary health care interventions [55]. However, one review noted that costing methods varied across studies, making it difficult to generate clear conclusions. The same review also noted that the opportunity costs borne by CHWs for volunteering their time were inadequately accounted for [33]. Table 9 summarizes findings from the review literature on cost-effectiveness.

In HICs, interventions delivered by CHWs to reduce triggers for childhood asthma brought cost savings [56, 57]. Another HIC study reported cost savings associated with peer support for breastfeeding [58]. Three reviews found inconclusive or no evidence on cost-effectiveness: vaccination promotion in LMICs [59], control of vascular diseases in HICs [60], and outreach to underserved groups in the USA [25].

Integration into health systems

The integration of CHW programs into the health system is reported in many reviews to be a key enabler [14, 15, 17, 19, 23, 24, 26, 32, 34, 35, 38, 61]. Pallas et al. [23] highlight that the integration of CHW programs into the agendas of the ministry of health, NGOs, and international donors can strengthen CHW programs and can also help bolster programs in times of political upheaval, loss of external donor funding, and reduced prioritization by the ministry of health. Integration that fosters respectful collaboration and communication between CHWs and higher-level staff can enable the health system to benefit from the unique, practical knowledge that CHWs have and can support CHW retention; this integration can enhance the acceptability and credibility of CHW programs [14, 15, 19, 24, 38, 44]. Table 10 summarizes findings from the review literature on health system integration.

Discussion

CHWs perform many roles in high-, middle-, and low-income country health systems and contribute to improving a range of health outcomes. However, their capacity is directly contingent on the support they receive from the health system. This review of reviews identifies a number of broad health system supports that optimize CHW programs and can be considered in light of context-specific factors to support health policy decision-making. It finds that CHW tasks should be clearly defined and should require a time commitment appropriate to the incentives/remuneration and support provided. Training should seek to impart both technical competency and socially oriented skills such as communication and counseling, including on confidentiality. Training appears to be more effective in imparting competencies by integrating hands-on practical components rather than just providing classroom learning and should be closely linked to ongoing supportive (rather than punitive or bureaucratic) supervision. Regular provision of supplies, such as medicines, communication tools and teaching aids, and transportation support, is essential for maintaining CHW program effectiveness. The review finds strong support for ensuring community embeddedness, as this is associated with CHW retention, motivation, performance, accountability, and support -- and ultimately affects the acceptability and uptake of CHWs’ health-related work. Linking CHWs to a supportive and functioning referral facility is often vital to CHW program effectiveness. Furthermore, programs must develop appropriate financial and non-financial incentives that take into account a range of factors, including the health system’s resource availability, CHW needs, rights, and expectations, and the tasks and time commitments required. The size of a CHW’s catchment population should be determined in response to the local reality, including population density, travel required, and workload.

As many countries are in the process of implementing new national CHW programs or strengthening current ones, the evidence synthesized in this review can help optimize these efforts. Ultimately, CHW programs are highly context specific. There are no standard blueprints that can be used to design and implement a CHW program. When developing programs, decisions must be made based on national, sub-national, district, and local realities.

This review also enabled the identification of several gaps in the review evidence. Relatively more (and higher quality) evidence is available on the effectiveness of CHWs in delivering specific health interventions than on effective approaches and cross-cutting strategies to integrate and support CBPs in health systems and optimize their performance [62]. There is little discussion in the review literature on the rights and needs of CHWs (with notable exceptions [36, 41]), on effective approaches to training and supervision, on CHWs as community change agents, as multisectorial actors, and on the influence of health system decentralization, social accountability, and governance.

Effectively addressing population needs for Universal Health Coverage with realistically available resources requires harnessing opportunities from the education and deployment of CHWs as members of inter-professional primary health care teams [1]. Countries should develop policies and mechanisms to integrate CHWs with the health system so as to enable these cadres to benefit from health system support and to enable the health system to achieve optimal benefit from CHWs [63]. Health system integration should foster respectful communication and collaboration between CHWs and other health system actors.

Integration of CHWs with health systems requires their inclusion into public policies, including those related to national human resources for health planning, governance, legal frameworks, and financing for health services. The requisite inputs of human and financial resources should be factored in at planning and budgeting stages and should be reflected in national health workforce and health sector strategies.

Policy dialogue about creating a strong role for CHWs in health systems must also address human and labor rights issues surrounding the CHW workforce [64], the favorable consequences of employment of large numbers of CHWs for economic growth and social development [64,65,66], as well as for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals [67].

This review faced some limitations. In including a range of study types—meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and non-systematic reviews (e.g., scoping, narrative, realist reviews)—and synthesizing findings across a broad range of issues and contexts, it was not possible to assess the overall risk of bias in the findings or to systematically account for the variable quality of the included reviews. Furthermore, presenting findings synthesized from a range of reviews necessitated a high level of abstraction and limited our capacity to present specific and important details and findings from individual studies. We encourage readers to examine AMSTAR quality scores and strength of evidence assessments in Additional file 3 for specific articles and to return to the source materials referenced for more information on topics of interest. Our definition of CHWs may not match definitions used by other teams, leading to inclusions and exclusions that may not fit the needs of all readers. In including research from high-, middle-, and low-income countries, some findings from drastically different settings may be difficult to transfer and apply. In addition, we focused only on academic, peer-reviewed literature, likely missing out on important findings from the gray literature.

Conclusion

The findings from this review can be adapted to national contexts, where the available resources to support CHW programs are highly variable. Developing and strengthening CHW programs will involve taking into account existing evidence of CHW program effectiveness, weighing options in light of a country’s existing primary health care system and needs, making informed decisions involving all stakeholders, designing and implementing the best program possible, and then adjusting course on the basis of experience, monitoring and evaluation, and findings from rigorous implementation research. Future progress in improving CHW programs will depend not only on synthesizing existing evidence but also on supporting and funding research to continually advance the contextualized evidence on how to design and implement CHW programs to maximize effectiveness [68]. CHWs can play a key role in strengthening health systems to provide universal, comprehensive, and people-centered care that is equitable, culturally appropriate, and economically feasible [1].

Abbreviations

- AMSTAR:

-

Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews

- CHW:

-

Community-based health worker

- HIC:

-

High-income country

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- LMIC:

-

Low- and middle-income country

- NCD:

-

Non-communicable disease

- TBA:

-

Traditional birth attendant

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

WHO. The World Health Report 2008. Primary Health Care - now more than ever, vol. 26. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/2008/whr08_en.pdf

Perry HB, Zulliger R, Scott K, Javadi D, Gergen J, Shelley K, et al. Case studies of large-scale community health worker programs: examples from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, Iran, Nepal, Niger, Pakistan, Rwanda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Washington, DC; 2017. Available from: http://www.mcsprogram.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/CHW-CaseStudies-Globes.pdf

Schneider H, Okello D, Lehmann U. The global pendulum swing towards community health workers in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review of trends, geographical distribution and programmatic orientations, 2005 to 2014. Hum Resour Health. 2016;14(1):65.

Perry HB, Zulliger R, Rogers MM. Community health workers in low-, middle-, and high-income countries: an overview of their history, recent evolution, and current effectiveness. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:399–421.

Black RE, Taylor CE, Arole S, Bang A, Bhutta ZA, et al. Comprehensive review of the evidence regarding the effectiveness of community-based primary health care in improving maternal, neonatal and child health: 8. summary and recommendations of the Expert Panel. J Glob Health. 2017;7(1):010908.

Bhutta Z, Lassi ZS, Pariyo G, Huicho L. Global experience of community health workers for delivery of health related millennium developmental goals: a systematic review, country case studies, and recommendations for integration into national health systems. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: http://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/publications/alliance/Global_CHW_web.pdf

Hannay J, Heroux J. Community health workers and a culture of health: lessons from U.S. and global models - a learning report. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2016. Available from: https://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/reports/2016/rwjf430963.

Singh P. One million community health workers: global technical taskforce report. The Earth Institute, Columbia University; 2013. Available from: http://1millionhealthworkers.org/files/2013/01/1mCHW_TechnicalTaskForceReport.pdf.

Shojania KB, Bero LA. Taking advantage of the explosion of systematic reviews: an efficient MEDLINE search strategy. Eff Clin Pr. 2001;4(4):157–62.

Wilczynski N, Haynes R. Hedges Team. Embase search strategies achieved high sensitivity and specificity for retrieving methodologically sound systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(1):29–33.

WHO. Working together for health: The World Health Report 2006, vol. 19. Genea: World Health Organization; 2006. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/2006/whr06_en.pdf.

Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells G a, Boers M, Andersson N, Hamel C, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7(10):10.

South J, Meah A, Bagnall A-M, Jones R. Dimensions of lay health worker programmes: results of a scoping study and production of a descriptive framework. Glob Health Promot. 2013;20(1):5–15.

Jaskiewicz W, Tulenko K. Increasing community health worker productivity and effectiveness: a review of the influence of the work environment. Hum Resour Health. 2012;10(1):38.

Kok MC, Dieleman M, Taegtmeyer M, Broerse JEW, Kane SS, Ormel H, et al. Which intervention design factors influence performance of community health workers in low- and middle-income countries? A systematic review. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30(9):1207–27.

Glenton C, Scheel IB, Lewin S, Swingler GH. Can lay health workers increase the uptake of childhood immunisation? Systematic review and typology. Trop Med Int Heal. 2011;16(9):1044–53.

Glenton C, Colvin CJ, Carlsen B, Swartz A, Lewin S, Noyes J, et al. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of lay health worker programmes to improve access to maternal and child health: qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;10:CD010414.

Pereira IC, Oliveira MAC. O trabalho do agente comunitário na promoção da saúde: revisão integrativa da literatura. Rev Bras Enferm. 2013;66(3):412–9.

Campbell C, Scott K. Retreat from Alma Ata? The WHO’s report on Task Shifting to community health workers for AIDS care in poor countries. Glob Public Health. 2011;6(2):125–38.

Patel AR, Nowalk MP. Expanding immunization coverage in rural India: a review of evidence for the role of community health workers. Vaccine. 2010;28(3):604–13.

Ruizendaal E, Dierickx S, Peeters Grietens K, Schallig HDFH, Pagnoni F, Mens PF. Success or failure of critical steps in community case management of malaria with rapid diagnostic tests: a systematic review. Malar J. 2014;13:229.

Ribeiro Sarmento D. Traditional Birth Attendance (TBA) in a health system: what are the roles, benefits and challenges: a case study of incorporated TBA in Timor-Leste. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2014;13(1):12.

Pallas SW, Minhas D, Pérez-Escamilla R, Taylor L, Curry L, Bradley EH, et al. Community health workers in low- and middle-income countries: what do we know about scaling up and sustainability? Am J Public Health. 2013;103(7):74–82.

Kok MC, Kane SS, Tulloch O, Ormel H, Theobald S, Dieleman M, et al. How does context influence performance of community health workers in low- and middle-income countries? Evidence from the literature. Heal Res Policy Syst. 2015;13(1):13.

Viswanathan M, Kraschnewski J, Nishikawa B, Morgan LC, Thieda P, Honeycutt A, et al. Outcomes of community health worker interventions. Evidence Report/Technology assessment. No 181. 2009. Prepared for: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD by RTI International–University of North Carolina Evidence-based Practice Center, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina.

Sunguya BF, Mlunde LB, Ayer R, Jimba M. Towards eliminating malaria in high endemic countries: the roles of community health workers and related cadres and their challenges in integrated community case management for malaria: a systematic review. Malar J. 2017;16(1):10.

Bosch-Capblanch X, Marceau C. Training, supervision and quality of care in selected integrated community case management (iCCM) programmes: a scoping review of programmatic evidence. J Glob Health. 2014;4(2):20403.

Celletti F, Wright A, Palen J, Frehywot S, Markus A, Greenberg A, et al. Can the deployment of community health workers for the delivery of HIV services represent an effective and sustainable response to health workforce shortages? Results of a multicountry study. AIDS. 2010;24(suppl 1):S45–57.

Bosch-Capblanch X, Garner P. Primary health care supervision in developing countries. Trop Med Int Heal. 2008;13(3):369–83.

Bosch-Capblanch X, Liaqat S, Garner P. Managerial supervision to improve primary health care in low- and middle-income countries (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;9:CD006413.

Hill Z, Dumbaugh M, Benton L, Ka K, Strachan DL, Asbroek A, et al. Supervising communtiy health workers n low-income countries- a review of impact and implementation issues. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:1–10.

Bemelmans M, Baert S, Negussie E, Bygrave H, Biot M, Jamet C, et al. Sustaining the future of HIV counselling to reach 90–90-90: a regional country analysis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19:20751.

Paintain LS, Willey B, Kedenge S, Sharkey A, Kim J, Buj V, et al. Community health workers and stand-alone or integrated case management of malaria: a systematic literature review. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;91(3):461–70.

Baatiema L, Sumah AM, Tang PN, Ganle JK. Community health workers in Ghana: the need for greater policy attention. BMJ Glob Health. 2016;1(4):e000141.

WHO, Global Health Workforce Alliance. Global experience of community health workers for delivery of health related millennium development goals. Geneva; World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: http://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/publications/alliance/Global_CHW_web.pdf.

Kane S, Kok M, Ormel H, Otiso L, Sidat M, Namakhoma I, et al. Limits and opportunities to community health worker empowerment: a multi-country comparative study. Soc Sci Med. 2016;164:27–34.

Smith HJ, Colvin CJ, Richards E, Roberson J, Sharma G, Thapa K, et al. Programmes for advance distribution of misoprostol to prevent post-partum haemorrhage: a rapid literature review of factors affecting implementation. Health Policy and Planning. 2016;31:102–13.

Zulu JM, Kinsman J, Michelo C, Hurtig AK. Integrating national community-based health worker programmes into health systems: a systematic review identifying lessons learned from low- and middle-income countries. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(987):1–17.

Ma Q, Tso LS, Rich ZC, Hall BJ, Beanland R, Li H, et al. Barriers and facilitators of interventions for improving antiretroviral therapy adherence: a systematic review of global qualitative evidence. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(1):1–13.

Miyake S, Speakman EM, Currie S, Howard N. Community midwifery initiatives in fragile and conflict-affected countries: a scoping review of approaches from recruitment to retention. Health Policy and Planning. 2017;32:21–33.

Bhatia K. Community health worker programs in India: a rights-based review. Perspect Public Health. 2014;134(5):276–82.

Gogia S, Ramji S, Gupta P, Gera T, Shah D, Mathew JL, et al. Community based newborn care: a systematic review and meta-analysis of evidence. Indian Pediatr. 2011;48(7):537–46.

Brownstein JN, Chowdhury FM, Norris SL, Horsley T, Jack L, Zhang X, et al. Effectiveness of community health workers in the care of people with hypertension. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(5):435–47.

Källander K, Tibenderana JK, Akpogheneta OJ, Strachan DL, Hill Z, Asbroek A, et al. Mobile health (mhealth) approaches and lessons for increased performance and retention of community health workers in lowand middle-income countries: a review. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(1):1–13.

Mercer C, Byrth J, Jordan Z. The experiences of Aboriginal health workers and non-Aboriginal health professionals working collaboratively in the delivery of health care to Aboriginal Australians: a systematic review. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Reports. 2014;12(3):274–418.

Darmstadt GL, Lee ACC, Cousens S, Sibley LM, Bhutta ZA, Donnay F, et al. 60 million non-facility births: who can deliver in community settings to reduce intrapartum-related deaths? Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2009;107:S89–S112.

Vouking MZ, Tamo VC, Mbuagbaw L. The impact of community health workers (CHWs) on Buruli ulcer in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;15(19):1–7.

Kane SS, Gerretsen B, Scherpbier R, Dal Poz M, Dieleman M. A realist synthesis of randomised control trials involving use of community health workers for delivering child health interventions in low and middle income countries. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10(1):286.

Darmstadt GL, Baqui AH, Choi Y, Bari S, Rahman SM, Mannan I, et al. Validation of community health workers’ assessment of neonatal illness in rural Bangladesh. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87(1):12–9.

Mwai G, Mburu G, Torpey K, Frost P, Ford N, Seeley J. Role and outcomes of community health workers in HIV care in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:1–14.

Bornstein VJ, Stotz EN. Concepções que integram a formação e o processo de trabalho dos agentes comunitários de saúde: uma revisão da literatura. Cien Saude Colet. 2008;13(1):259–68.

Kredo T, Adeniyi FB, Bateganya M, Pienaar ED. Task shifting from doctors to non-doctors for initiation and maintenance of antiretroviral therapy (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;7:CD007331.

Mdege ND, Chindove S, Ali S. The effectiveness and cost implications of task-shifting in the delivery of antiretroviral therapy to HIV-infected patients: a systematic review. Health Policy Plan. 2013;28(3):223–36.

van Ginneken N, Tharyan P, Lewin S, Rao G, Meera S, Pian J, et al. Non-specialist health worker interventions for the care of mental, neurological, and substance-abuse disorders in low- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;11:CD009149.

Vaughan K, Kok MC, Witter S, Dieleman M. Costs and cost-effectiveness of community health workers: evidence from a literature review. Hum Resour Health. 2015;13(1):71.

Raphael JL, Rueda A, Lion KC, Giordano TP. The role of lay health workers in pediatric chronic disease: a systematic review. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13(5):408–20.

Postma J, Karr C, Kieckhefer G. Community health workers and environmental interventions for children with asthma: a systematic review. J Asthma. 2009;46(1):564–76.

Kaunonen M, Hannula L, Tarkka MT. A systematic review of peer support interventions for breastfeeding. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(13–14):1943–54.

Corluka A, Walker DG, Lewin S, Glenton C, Scheel IB. Are vaccination programmes delivered by lay health workers cost-effective? A systematic review. Hum Resour Health. 2009;7:81.

Small N, Blickem C, Blakeman T, Panagioti M, Chew-Graham Ca., Bower P. Telephone based self-management support by “lay health workers” and “peer support workers” to prevent and manage vascular diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:533.

Boyce MR, O’Meara WP. Use of malaria RDTs in various health contexts across sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):470.

Maher D, Cometto G. Research on community-based health workers is needed to achieve the sustainable development goals. Bull World Heal Organ. 2016;94(11):786.

WHO. Global strategy on human resources for health: workforce 2030. Synthesis paper of the thematic working groups. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016. Available from: http://www.who.int/hrh/resources/pub_globstrathrh-2030/en/.

ILO. C149 – Nursing Personnel Convention, 1977 (No. 149). Convention concerning Employment and Conditions of Work and Life of Nursing Personnel. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Office; 1977. Available from: http://www.ilo.org/dyn/.

WHO. Working for health and growth: Investing in the health workforce. Geneva, Switzerland: High-Level Commission on Health Employment and Economic Growth. World Health Organization; 2016. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250047/9789241511308-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

WHO, Horton R, Araujo EC, Bhorat H, Bruysten S, Jacinto CG, et al. Final report of the expert group to the High-Level Commission on Health Employment and Economic Growth. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250040/9789241511285-eng.pdf?sequence=1

United Nations. Sustainable Development Goal 8: Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all. Geneva, Switzerland: 2015. Available from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg8

Frymus D, Kok M, Koning K De, Quain E. Community health workers and universal health coverage: knowledge gaps and a need based global research agenda by 2015. Geneva, Switzerland: Global Health Workforce Alliance. 2013. Available from: http://www.who.int/entity/workforcealliance/knowledge/resources/CHWsResearch_Agenda_by2015.pdf.

Dale J, Caramlau I, Lindenmeyer A, Williams SM. Peer support telephone call interventions for improving health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;1:CD006903.

Lizarondo L, Kumar S, Hyde L, Skidmore D. Allied health assistants and what they do: a systematic review of the literature. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2010;3:143–53.

Stanhope J, Pearce C. Role, implementation, and effectiveness of advanced allied health assistants: a systematic review. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2013;6:423–34.

Jones CCG, Jomeen J, Hayter M. The impact of peer support in the context of perinatal mental illness: a meta-ethnography. Midwifery. 2014;30(5):491–8.

Rahman A, Fisher J, Bower P, Luchters S, Tran T, Yasamy MT. Interventions for common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:593–601.

Petersen I, Fairall L, Egbe CO, Bhana A. Optimizing lay counsellor services for chronic care in South Africa: a qualitative systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;95(2):201–10.

Horey D, Street AF, O’Connor M, Peters L, Lee SF. Training and supportive programs for palliative care volunteers in community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;7(7):CD009500.

Kamal-Yanni MM, Potet J, Saunders PM. Scaling-up malaria treatment: a review of the performance of different providers. Malar J. 2012;11(1):414.

Flynn DE, Johnson C, Sands A, Wong V, Figueroa C, Baggaley R. Can trained lay providers perform HIV testing services? A review of national HIV testing policies. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):20.

Noordam AC, Barberá Laínez Y, Sadruddin S, van Heck PM, Chono AO, Acaye GL, et al. The use of counting beads to improve the classification of fast breathing in low-resource settings: a multi-country review. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30(6):696–704.

Wadler BM, Judge CM, Prout M, Allen JD, Geller AC. Improving breast cancer control via the use of community health workers in South Africa: a critical review. J Oncol. 2011:150423.

Scott V, Gottschalk LB, Wright KQ, Twose C, Bohren MA, Schmitt ME, et al. Community health workers’ provision of family planning services in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review of effectiveness. Stud Fam Plan. 2015;46(3):241–61.

Malarcher S, Meirik O, Lebetkin E, Shah I, Spieler J, Stanback J. Provision of DMPA by community health workers: what the evidence shows. Contraception. 2011;83(6):495–503.

Sibley LM, Sipe TA, Barry D. Traditional birth attendant training for improving health behaviours and pregnancy outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8(8):CD005460.

Silveira Feyer IS, Monticelli M, Volkmer C, Burigo RA. Brazilian scientific publications of obstetrical nurses on home delivery: systematic literature review 1 Publicações Científicas Brasileiras De Enfermeiras Obstétricas Sobre Parto Domiciliar: Revisão Sistemática Publicaciones Científicas Brasileiras De. Text Context Nurs. 2013;22(1):247–56.

Sazawal S, Black RE. Effect of pneumonia case management on mortality in neonates, infants, and preschool children: a meta-analysis of community-based trials. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3(9):547–56.

Amouzou A, Morris S, Moulton LH, Mukanga D. Assessing the impact of integrated community case management (iCCM) programs on child mortality: review of early results and lessons learned in sub-Saharan Africa. J Glob Health. 2014;4(2):20411.

Kabaghe AN, Visser BJ, Spijker R, Phiri KS, Grobusch MP, van Vugt M. Health workers’ compliance to rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) to guide malaria treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Malar J. 2016;15(1):163.

Hou S-I, Roberson K. A systematic review on US-based community health navigator (CHN) interventions for cancer screening promotion--comparing community- versus clinic-based navigator models. J Cancer Educ. 2015;30(1):173–86.

Little TV, Wang ML, Castro EM, Jimenez J, Rosal MC. Community health worker interventions for Latinos with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Curr Diab Rep. 2014;14(12):1–16.

Cherrington A, Ayala GX, Amick H, Scarinci I, Allison J, Corbie-Smith G. Applying the community health worker model to diabetes management: using mixed methods to assess implementation and effectiveness. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19(4):1044–59.

Hunt CW, Grant JS, Appel SJ. An integrative review of community health advisors in type 2 diabetes. J Community Health. 2011;36(5):883–93.

Gogia S, Sachdev HPS. Home-based neonatal care by community health workers for preventing mortality in neonates in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. J Perinatol. 2016;36(S1):S55–73.

Bhutta ZA, Soofi S, Cousens S, Mohammad S, Memon ZA, Ali I, et al. Improvement of perinatal and newborn care in rural Pakistan through community-based strategies: a cluster-randomised effectiveness trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9763):403–12.

Lassi ZS, Bhutta ZA. Community-based intervention packages for reducing maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality and improving neonatal outcomes (Review). Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2015;(3):CD007754.

Sibley LM, Sipe TA. Transition to skilled birth attendance: is there a future role for trained traditional birth attendants? J Health Popul Nutr. 2006;24(4):472–8.

Hall BJ, Rachel KS, Mellanye B, Sze L, Qingyan T, Doherty M, et al. Barriers and facilitators to interventions improving retention in HIV care: a qualitative evidence meta-synthesis. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(6):1755–67.

Tso LS, Best J, Beanland R, Doherty M, Lackey M, Ma Q, et al. Facilitators and barriers in HIV linkage to care interventions: qualitative evidence review. AIDS. 2016;30(10):1639–53.

Mutamba BB, van Ginneken N, Smith Paintain L, Wandiembe S, Schellenberg D. Roles and effectiveness of lay community health workers in the prevention of mental, neurological and substance use disorders in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. BMC Heal Serv Res. 2013;13:412.

Costa EF, Guerra PH, dos Santos TI, Florindo AA. Systematic review of physical activity promotion by community health workers. Prev Med. 2015;81:114–21.

Gibbons MC, Tyrus NC. Systematic review of U.S.-based randomized controlled trials using community health workers. Prog Community Heal Partnerships Res Educ Action. 2007;1(4):371–81.

Norris SL, Chowdhury FM, Van Le K, Horsley T, Brownstein JN, Zhang X, et al. Effectiveness of community health workers in the care of persons with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2006;23:544–56.

Agarwal S, Perry HB, Long LA, Labrique AB. Evidence on feasibility and effective use of mHealth strategies by frontline health workers in developing countries: systematic review. Trop Med Int Heal. 2015;20(8):1003–14.

Braun R, Catalani C, Wimbush J, Israelski D. Community health workers and mobile technology: a systematic review of the literature. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):4–9.

Stacciarini J-MR, Rosa A, Ortiz M, Munari DB, Uicab G, Balam M. Promotoras in mental health. Fam Community Health. 2012;35(2):92–102.

Rhodes SD, Foley KL, Zoneta CS, Bloom FR. Lay health advisor interventions among Hispanics/Latinos: a qualitative systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(5):418–27.

Prost A, Colbourn T, Seward N, Azad K, Coomarasamy A, Copas A, et al. Women’s groups practising participatory learning and action to improve maternal and newborn health in low-resource settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;381(9879):1736–46.

Hoeft TJ, Fortney JC, Patel V, Unützer J. Task-sharing approaches to improve mental health care in rural and other low-resource settings: a systematic review. J Rural Heal. 2016;0:1–15.

Wouters E, Van Damme W, van Rensburg D, Masquillier C, Meulemans H. Impact of community-based support services on antiretroviral treatment programme delivery and outcomes in resource-limited countries: a synthetic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):194.

Shommu NS, Ahmed S, Rumana N, Barron GRS, McBrien KA, Turin TC. What is the scope of improving immigrant and ethnic minority healthcare using community navigators: a systematic scoping review. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):6.

Zhou K, Fitzpatrick T, Walsh N, Kim JY, Chou R, Lackey M, et al. Articles Interventions to optimise the care continuum for chronic viral hepatitis: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(12):1409–22.

Abbott LS, Elliott LT. Eliminating health disparities through action on the social determinants of health: a systematic review of home visiting in the United States, 2005–2015. Public Health Nurs. 2017;34(1):2–30.

McCollum R, Gomez W, Theobald S, Taegtmeyer M. How equitable are community health worker programmes and which programme features influence equity of community health worker services? A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:419.

Giugliani C, Harzheim E, Duncan MS, Duncan BB. Effectiveness of community health workers in Brazil: a systematic review. J Ambul Care Manage. 2011;34(4):326–38.

Ehiri JE, Gunn JKL, Center KE, Li Y, Rouhani M, Ezeanolue EE. Training and deployment of lay refugee/internally displaced persons to provide basic health services in camps: a systematic review. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:23902.

Gilmore B, McAuliffe E. Effectiveness of community health workers delivering preventive interventions for maternal and child health in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):847.

Christopher JB, Le May A, Lewin S, Ross DA. Thirty years after Alma-Ata: a systematic review of the impact of community health workers delivering curative interventions against malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoea on child mortality and morbidity in sub-Saharan Africa. Hum Resour Health. 2011;9:27.

Gogia S, Sachdev HS. Home visits by community health workers to prevent neonatal deaths in developing countries: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(9):658–66.

Wilson A, Gallos ID, Plana N, Lissauer D, Khan KS, Zamora J, et al. Effectiveness of strategies incorporating training and support of traditional birth attendants on perinatal and maternal mortality: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;343:d7102.

Lewin S, Munabi-Babigumira S, Glenton C, Daniels K, Bosch-Capblanch X, van Wyk BE, et al. Lay health workers in primary and community health care for maternal and child health and the management of infectious diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;3(3):CD004015.

Lee ACC, Chandran A, Herbert HK, Kozuki N, Markell P, Shah R, et al. Treatment of infections in young infants in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of frontline health worker diagnosis and antibiotic access. PLoS Med. 2014;11(10):e1001741.

Oyo-Ita A, Wiysonge CS, Oringanje C, Nwachukwu CE, Oduwole O, Meremikwu MM. Interventions for improving coverage of childhood immunisation in low- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;7:CD008145.

Glenton C, Khanna R, Morgan C, Nilsen ES. The effects, safety and acceptability of compact, pre-filled, autodisable injection devices when delivered by lay health workers. Trop Med Int Heal. 2013;18(8):1002–16.

Maravilla JC, Betts KS, Abajobir AA, Couto e Cruz C, Alati R. The role of community health workers in preventing adolescent repeat pregnancies and births. J Adolesc Health. Elsevier Inc. 2016;59:378–90.

Dawson AJ, Buchan J, Duffield C, Homer CSE, Wijewardena K. Task shifting and sharing in maternal and reproductive health in low-income countries: a narrative synthesis of current evidence. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29(3):396–408.

Chapman DJ, Morel K, Anderson AK, Damio G, Pérez-Escamilla R. Breastfeeding peer counseling: from efficacy through scale-up. J Hum Lact. 2010;26(3):314–26.

Palmas W, March D, Darakjy S, Findley SE, Teresi J, Carrasquillo O, et al. Community health worker interventions to improve glycemic control in people with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2015:1004–12.

Wells KJ, Luque JS, Miladinovic B, Vargas N, Asvat Y, Roetzheim RG, et al. Do community health worker interventions improve rates of screening mammography in the United States? A systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(8):1580–98.

Wahlbeck K, Cresswell J, Peija S, Parkkonen J. Interventions to mitigate the effects of poverty and inequality on mental health. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52(5):505–14.

Singla DR, Kohrt BA, Murray LK, Anand A, Chorpita BF, Patel V. Psychological treatments for the world: lessons from low- and middle-income countries. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2017;13:149–81.

Kew KM, Carr R, Crossingham I. Lay-led and peer support interventions for adolescents with asthma (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(8):CD012331.

Corley AG, Thornton CP, Glass NE. The role of nurses and community health workers in confronting neglected tropical diseases in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2016;10:1–24.

Reisman J, Arlington L, Jensen L, Louis H, Suarez-Rebling D, Nelson BD. Newborn resuscitation training in resource-limited settings: a systematic literature review. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2):e20154490.

Fulton BD, Scheffler RM, Sparkes SP, Auh EY, Vujicic M, Soucat A. Health workforce skill mix and task shifting in low income countries: a review of recent evidence. Hum Resour Health. 2011;9(1):1-11.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dena Javadi (Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, World Health Organization) and Elie Akl (American University in Beirut) for their helpful comments and inputs in the conceptualization and quality assurance of this analysis. We thank Valerie Caldas for her help with Additional file 3 and the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments.

Funding

This study was funded by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), through grants managed by the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research and the Global Health Workforce Alliance, partnerships hosted and administered by the World Health Organization. The funding body had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GC and HBP conceptualized and designed the study. MG developed and conducted the database searches. KS, SWB, GP, KDR, and HBP screened the references identified through the database searches using the inclusion and exclusion criteria and extracted data from the included articles. MG and SWB applied the quality assessment tool (AMSTAR) criteria to all included systematic reviews. KS analyzed and synthesized data and drafted the manuscript, under HBP’s guidance. HBP, GC, MG, KS, SWB, GP, and KDR provided critical intellectual feedback and assisted in revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

PUBMED search strategy. (DOCX 168 kb)

Additional file 2:

AMSTAR quality appraisal. (DOCX 37 kb)

Additional file 3:

Searchable Excel database summary of all reviews. (XLSX 351 kb)

Additional file 4:

Summary information by topic from the 122 reviews. (DOCX 129 kb)

Additional file 5:

Included and excluded articles. (DOCX 55 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Scott, K., Beckham, S.W., Gross, M. et al. What do we know about community-based health worker programs? A systematic review of existing reviews on community health workers. Hum Resour Health 16, 39 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-018-0304-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-018-0304-x