Abstract

Background

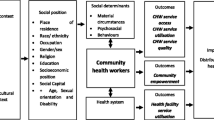

There has been a substantial increase in publications and interest in community health workers (CHWs) in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) over the last years. This paper examines the growth, geographical distribution and programmatic orientations of the indexed literature on CHWs in LMIC over a 10-year period.

Methods

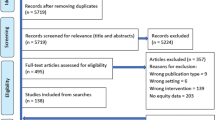

A scoping review of publications on CHWs from 2005 to 2014 was conducted. Using an inclusive list of terms, we searched seven databases (including MEDLINE, CINAHL, Cochrane) for all English-language publications on CHWs in LMIC. Two authors independently screened titles/abstracts, downloading full-text publications meeting inclusion criteria. These were coded in an Excel spreadsheet by year, type of publication (e.g. review, empirical), country, region, programmatic orientation (e.g. maternal-child health, HIV/AIDS, comprehensive) and CHW roles (e.g. prevention, treatment) and further analysed in Stata14. Drawing principally on the subset of review articles, specific roles within programme areas were identified and grouped.

Findings

Six hundred seventy-eight publications from 46 countries on CHWs were inventoried over the 10-year period. There was a sevenfold increase in annual number of publications from 23 in 2005 to 156 in 2014. Half the publications were reporting on initiatives in Africa, a third from Asia and 11 % from the Americas (mostly Brazil). The largest single focus and driver of the growth in publications was on CHW roles in meeting the Millennium Development Goals of maternal, child and neonatal survival (35 % of total), followed by HIV/AIDS (16 %), reproductive health (6 %), non-communicable diseases (4 %) and mental health (4 %). Only 17 % of the publications approached CHW roles in an integrated fashion. There were also distinct regional (and sometimes country) profiles, reflecting different histories and programme traditions.

Conclusions

The growth in literature on CHWs provides empirical evidence of ever-increasing expectations for addressing health burdens through community-based action. This literature has a strong disease- or programme-specific orientation, raising important questions for the design and sustainable delivery of integrated national programmes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

As has now been noted by many, the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) era saw a global resurgence of interest in the role of community health workers (CHWs) in health systems, an interest that is set to continue in new global health agendas [1]. The mobilization of international funding from bilateral, multilateral and private philanthropic sources has greatly increased investment in programmes to meet the MDG targets. Further, through the popularization of the concept of “task shifting”, the involvement of lay and community health workers has emerged as a rational strategy for addressing the vast shortfall in human resources impeding the roll-out of programmes in many countries.

A feature of countries that made the most progress in the health of their populations has been their investment in strategies that engage households and communities directly as part of primary health care [2]. An expanding list of countries with large-scale and stable CHW programmes and a growing evidence base on the effectiveness of CHWs in achieving specific health outcomes [3–6] have brought renewed global confidence in CHWs. A number of significant international consensus statements have recommended that CHW programmes be integrated into health systems, increasingly linking these to the concept of universal health coverage (UHC) [7–9].

Driven by different imperatives and needs, CHW initiatives have taken a variety of regional- and country-specific forms. Some, such as the Brazilian Programa Saúde da Famiília, Ethiopia’s health extension workers and the Behvarzs of Iran, have been part of broader social, political and health sector change. In several Asian countries (Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal), CHW programmes have been established in response to the public health challenge of high maternal, neonatal and under-5 mortality. In the HIV-affected countries of southern Africa, home-based care and support emerged organically through local community and non-governmental organizations as a response to overwhelming care and social needs. In other African countries, Global Health Initiatives and partnerships focused on malaria and childhood illness have been influential. CHWs and CHW programmes are thus a broad umbrella concept and practice under which a diverse array of programmatic priorities, roles and forms of community involvement in health and health care delivery exist.

How are this diversity and the global pendulum swing towards CHWs reflected in the research on CHWs and CHW programmes? We report on a scoping review of trends, geographical distribution and programmatic orientations in the indexed literature on CHWs in low- and middle-income countries over a 10-year period (2005–2014). A scoping review aims to “map the existing literature in a field of interest in terms of the volume, nature and characteristics of the primary research” [10]. The purpose of this review is thus not to appraise or synthesize the evidence base for effectiveness, feasibility or impact of CHWs, or to assess the quality of research, but rather to present a descriptive account of the contours of a rapidly evolving and heterogenous field.

Specifically, we were animated by the following questions:

-

1.

What are the trends in numbers of publications on CHWs?

-

2.

Which countries and regions are represented in these trends?

-

3.

What is the profile of health programmes and global health agendas (e.g. maternal-child health, HIV/TB)?

-

4.

What types of CHW roles (e.g. prevention, treatment, social mobilization) are being foregrounded?

-

5.

What does it suggest for future thinking on CHW programmes?

Our definition of a CHW for the purpose of this review is that proposed by Naimoli et al. [11] as “a health worker who receives standardized training outside the formal nursing or medical curricula to deliver a range of basic health, promotional, educational, and outreach services, and who has a defined role within the community system and larger health system.” In this review, we focus on those cadres whose activities are primarily community- rather than facility based.

Methods

Scoping review methodology

The review methodology followed broadly the steps proposed by Levac et al. [12]. HS and UL developed the scoping review questions (and coding schemes) based on previous literature reviews. After an initial search, the volume of new literature in recent years immediately became apparent. Since we were primarily interested in trends and patterns, we decided to limit the scope of the search to the indexed literature and focus on a 10-year period. In October 2015, we searched the following electronic databases through EBSCOhost: Academic Search Premier, Africa-Wide Information, CINAHL, PsycINFO, SocINDEX and MEDLINE, for all English-language publications on CHWs, indexed from 2005 to 2014, and in countries defined by the World Bank as low- and middle income (http://data.worldbank.org/news/new-country-classifications-2015). We also searched the Cochrane database for systematic reviews on CHWs.

Recognizing the wide diversity of forms and titles of CHWs across the globe, we developed an inclusive list of search terms (Table 1). However, we deliberately excluded certain terms, such as traditional birth attendants and facility-based lay counsellors, as these would have touched on significant other bodies of literature.

The search was conducted sequentially with all the EBSCOhost databases except MEDLINE searched together in the first step, followed by the search of MEDLINE in a second step. Each step yielded 5635 and 1445 hits, respectively.

From October 2015 to January 2016, two authors (HS and DO) independently screened the titles and abstracts obtained in these searches, based on the inclusion criteria (Table 1). In this initial process, we selected a total of 897 publications, which were entered in a database (Mendeley) and full texts downloaded. Entries were then independently coded by two authors (HS and DO) in an Excel spreadsheet following the scheme outlined in Table 2. In an iterative process that involved removing publications that did not meet the inclusion criteria, and adding relevant publications identified in the subset of review papers, a final total of 678 publications was selected for analysis.

Coding relied on the abstract in the first instance, with further verification based on the full-length article, if the abstract was not sufficient. We categorized each entry into year of publication, country and region, and type of publication—empirical, review or “analysis”. Empirical pieces reported research findings (qualitative or quantitative), and reviews were formal appraisals of the literature based on an identifiable search strategy. Some papers used “review” in the title in a more colloquial sense but were substantive reflections or commentaries, drawing on the literature, but not adopting a structured review strategy. We categorized these papers as “analyses”. Publications were also categorized by programmatic focus based on the conventionally accepted approaches (such as maternal-child health, malaria, reproductive health, comprehensive), drawing firstly on the title and abstract, and if this was not stated by scanning the full-length paper for a description of CHW roles. Additional file 1: Table S1 gives a detailed breakdown of the items included under each of the codes. We also noted the type of role such as treatment or prevention or both—performed by the CHWs. The coded items in the Excel spreadsheet were imported into Stata (Version 14) for descriptive quantitative analysis. A qualitative, thematic analysis of key roles within each programmatic area was done, drawing on the subset of review and multi-country articles in the first instance, followed by reading of individual papers if the reviews were judged not sufficient.

Limitations

The findings reported are not a full inventory of all research and publications on CHWs but rather the trends and patterns of a delimited body of literature in the field, through one search process. Given the volume of publications, we did not conduct a grey literature search. However, we recognize there are significant and influential publications [9, 13–15] and consensus statements [7, 16] in this sphere, whose insights have not necessarily made their way into the indexed literature.

Choices were made in the classification of the paper’s programmatic focus. For example, the prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) interventions, because they overlap with general maternal health (breastfeeding, antenatal care), were classified under maternal-child health (MCH) rather than HIV/TB. On the other hand, studies evaluating intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in children (IPTc) were classified under malaria because they most often emerged from a malaria programmatic focus. However, integrated community case management interventions, combining pneumonia and malaria treatment of children, were classified under MCH. The specific choices are reflected in Additional file 1: Table S1.

To limit the scope of the review, we also excluded facility-based cadres as it would have meant assessing a growing body of work on task shifting within health facilities, especially in HIV-affected countries where lay counsellors have become an integral part of primary health care teams. Unfortunately, this also excluded significant developments in the field of mental health (see, for example, [17, 18]).

This review does not address a key preoccupation in the literature on the support and systems dimensions of CHW programmes, such as supervision, retention, motivation, monitoring and financing of CHWs.

Findings

Overall profile, trends and geographical distribution

Of the 678 papers, 604 (89 %) were empirical pieces, 55 (8 %) were reviews and 19 (3 %) were analyses. There was a nearly sevenfold growth in annual number of publications over the period, from 23 in 2005 to 156 in 2014 (Fig. 1).

The papers reported experiences in 46 countries (Additional file 2: Figure S1), with 17 countries contributing at least 10 publications each, amongst them the globally recognized national CHW initiatives (Table 3). Half of the publications came from the Africa Region, just under a third from the Asia/Pacific Region, and 6.5 % had a global perspective. Iran was the only country contributing experiences from the Middle East Region, and the Brazilian programme accounted for 80 % of publications from Latin America, possibly reflecting the English-language bias of the review (Additional file 3: Table S2). Three middle-income countries—South Africa, India and Brazil—each contributed 60 or more papers, together making up 30 % of the total publications.

Programmatic focus

The profile of programmatic foci in the publications, by region and country, is summarized in Table 3 and provided in full in Additional file 3: Table S2.

Maternal-child health focus

By far the most commonly reported CHW roles were those focused on maternal-child health (MCH), accounting for over a third of the total papers as well as the subset of reviews. When comparing the first and second halves of the review period, MCH was also the biggest driver of growth in publications (Fig. 2). The global emergence and promotion of integrated community case management (iCCM) of childhood illness, particularly in Africa, is the single most important element in this. iCCM is a community and CHW-based child survival strategy, adopted by WHO and UNICEF [16]. Three special editions on iCCM were produced in the review period, one in 2012 (American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene) and two in 2014 (Ethiopian Medical Journal, Journal of Global Health), accounting for the spikes in publications in those 2 years (Fig. 1).

CHW roles in MCH were clustered into three broad areas:

-

Maternal and newborn health, including birth preparedness and distribution of misoprostol to prevent post partum haemorrhage in home deliveries [19, 20]; postnatal home visiting, umbilical cord care, thermal care, promotion of exclusive breast feeding and treatment of neonatal infection; [21–23] and support to mothers and infants for the prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV [24–26].

-

Promotion of child health, including uptake of immunization [27]; nutrition, including breast feeding, micronutrient supplementation and supplemental feeding [28]; community management of malnutrition [29]; and early childhood development [30, 31].

-

Treatment of childhood illness [32, 33] in particular the iCCM strategy [34]. iCCM combines the diagnosis and treatment of malaria with artemisinin combination therapy (ACT), pneumonia with oral antibiotics and diarrhoea with zinc and oral rehydration salts (ORS). It has been facilitated by the development of rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) for malaria, thus allowing for more accurate diagnosis of fever in young children.

iCCM has been promoted by WHO and UNICEF across sub-Saharan Africa and integrated to varying degrees in country CHW initiatives [35]. It was the most common theme in comparative or cross-country publications from Africa (19 out of 34 papers). While MCH was also a dominant focus of CHW studies from Asia, these programmes were orientated to maternal and newborn health and were more preventive and promotive in approach. They also tended to be tailored programmes, developed in context-specific ways and involving a greater level of community mobilization and participation in their design [36]. In contrast to the African continent, there were no multi-country empirical studies from Asia.

Comprehensive focus

Seventeen percent of publications approached CHW roles comprehensively. Publications in this category included systematic reviews addressing the effectiveness of CHWs across a number of programmatic areas, including maternal-child health, HIV and TB [3, 6]. They also included reports or evaluations of provincial or national programmes, amongst them the recognized ones listed in Table 3 (see, for example, [37–40]).

In general, the comprehensive programmes were large-scale government initiatives that combined disease/programme-specific tasks with social, environmental and health surveillance roles. The activities spanned prevention, promotion, treatment and community mobilization. Table 4 outlines the roles of three typical cadres, the health extension workers (HEWs) in Ethiopia, the health surveillance assistant (HSAs) in Malawi and the Behvarzs in Iran. These cadres are government employed and receive basic training ranging from 3 months (HSA) to 1 year (HEW) and 2 years (Behvarz).

As the evidence base on CHW roles and access to diagnostic and treatment technologies expand, a key risk in comprehensive programmes is role overload. A number of papers addressed this, outlining the need to maintain realistic expectations and workloads of CHWs and proposing new ways of configuring community-based services, such as specialization of functions and a division of labour [41, 42]. Related to this is the ongoing preoccupation with maintaining an appropriate balance between prevention, treatment, facilitating access and community mobilization [43].

Other programmatic foci

The next biggest programmatic focus of publications was on HIV/AIDS and TB (16 %). More than three quarters (76 %) of the publications with this focus came from the heavily AIDS-affected countries of sub-Saharan Africa (particularly South Africa) (Additional file 3: Table S2). The CHW roles in HIV/AIDS and TB were mostly oriented towards care, counselling, adherence and social support and promoting patient self-management, with some elements of prevention and promotion [44]. In an earlier period, they were focused on palliative home-based care and on implementing the WHO-advocated “DOTS” (Directly Observed, Short Course treatment) for TB [45, 46]. With the advent of antiretroviral therapy, roles shifted towards home-based HIV testing; referral for, or home initiation of, antiretroviral therapy (ART); and community-based adherence support and follow-up of care for ART [47, 48] and TB treatment [49], increasingly as integrated programmes [50, 51]. In a number of countries, the mobilization of community health workers for HIV/AIDS appears to have emerged as a parallel development alongside other programmatic initiatives, producing a mixed profile of lay health work and posing challenges of local coordination and integration [52, 53].

Ten percent of publications reported on the role of CHWs in the control of malaria (apart from their contribution to iCCM). These included community case management or home management of malaria with or without the use of rapid diagnostic tests [54], distribution of intermittent preventive treatment (IPT) to pregnant women and children [55–57] and the promotion of insecticide-impregnated bed nets [58].

CHWs have long established roles in family planning (often referred to as community-based distributors) and commonly provided as vertical programmes [59]. Several papers reported on experiences with CHWs providing injectable contraceptives [4], including the more recent contraceptive implants (Implanon) [60]. CHWs have also been involved in promoting cervical [61] and breast cancer screening [62, 63].

Other established specialist CHW roles reported in the period include the distributors of ivermectin to treat river blindness in the “community-directed interventions” [64] developed by the WHO/TDR-supported African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control. Similar roles were also reported for other “neglected tropical diseases” such as schistosomiasis [65] and trachoma [66]. CHWs were also deployed in the early detection of Buruli ulcer [67] and visceral leishmaniasis [68] in high-burden areas.

Emerging programme foci

Reflecting changing demographic and epidemiological profiles, a small but steady number of publications across years and regions addressed CHW roles in non-communicable diseases. They included primary preventive programmes for cardiovascular disease and diabetes, focusing on lifestyle risk factors such as physical activity, diet and smoking cessation in Thailand [69], India [70], Pakistan [71], Brazil [72] and Ghana [73]; community-based screening, referral and follow-up in Kenya [74], South Africa [75], Iran [76], Brazil [77] and Pakistan [78]; and population surveillance for NCDs in India [79]. There were no reviews within or across low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) of CHW roles in chronic disease care in the period.

A number of empirical papers and reviews reported on the integration of mental health into existing CHW initiatives [5]. In Pakistan, Lady Health Workers successfully provided cognitive-based therapies for perinatal depression [80]. In Malawi and Kenya, CHWs were given general training in mental health awareness, identification and family support [81, 82]. In Brazil, community health agents screened for dementia and depression in the elderly [83, 84]. In India, community-based care for schizophrenia and dementia sufferers was evaluated as part of “collaborative care” (in a team with professionals) [85, 86].

Regional variations

Programmatic emphases varied between regions (Fig. 3). In Africa, with high burdens of malaria and HIV, publications were more evenly distributed between HIV/TB, malaria and MCH. In Asia, MCH dominated as a programmatic focus, although with significant nodes of development in mental health and NCDs. The comprehensive orientation of the Latin American publications reflects the influence of the Brazilian Family Health Programme, which is delivered with the close support of health professionals and primary health care facilities.

Types of roles

Where this was identifiable (n = 615 papers), the roles of CHWs along the promotion-prevention-treatment continuum were coded. These were broadly clustered in four areas (Fig. 4): (1) diagnosis and treatment (notably in iCCM and malaria); (2) prevention and promotion, spanning the distribution of preventive technologies (such as contraceptives), to education (such as newborn health, breast feeding), to processes of social mobilization; (3) screening, referral and surveillance activities, such as early detection of cancers or chronic disease; and (4) counselling, care and adherence support for adults receiving treatment for chronic conditions (such as HIV/TB, mental illness). One quarter of the papers reported roles spanning two or more of these areas, with several papers suggesting the importance of combined roles in the community legitimacy of CHWs [43, 87].

Within-country plurality

Publications most often focused on evaluating or describing the work of one type of CHW. However, even in countries with recognized national programmes, the papers from this country, when brought together as a collection, portrayed a more diverse reality. In Ethiopia, for example, where the health extension workers (HEWs) are the recognized CHWs, at least two other community-based workers in communities were described: the community-based reproductive agents delivering contraceptive technologies [88] and community AIDS volunteers linked to NGOs and ART treatment programmes [53, 89]. Within the Health Extension Programme itself, HEWs relate to a cascade of community actors: they mobilize volunteer community health workers, also referred to as the Health Development Army, who, in turn, nominate female household members for training as “model households” [39, 90].

In Uganda, where community health workers are volunteers, and where roles and functions were less clearly defined nationally, the 34 papers in the collection described a plethora of disease- or programme-specific workers and interventions, including iCCM, maternal and new born health, reproductive health, malaria, onchocerciasis, antiretroviral therapy for HIV and palliative care.

Standing and Chowdhury [91] describe how community health workers in Bangladesh are positioned in dense and plural local health care environments, where they are but one player amongst the many informal, formal and traditional sources of care and healing which community members draw on. In such contexts, CHWs play a variety of different roles—as a generic provider linked to an agency (such as Building Resources Across Communities (BRAC)), specialized workers (e.g. reproductive health distributors), as agents that mediate relationships between households and the formal health system or as expert patients.

Discussion

There has been a large growth in publications on CHWs in recent years, most notably since 2011. This growth has been driven by the MDGs, especially those related to child survival, which have placed heavy emphasis on community-based activities. The integrated community case management strategy, in particular, was the product of a concerted global agenda setting process by an “epistemic community” of international NGOs, multilateral and bilateral agencies and academic actors, who developed and promoted a package of feasible interventions targeted at the major causes of child mortality [92].

Despite the extensive reliance on lay heath workers and greater levels of international funding flowing to HIV/AIDS [93], there were fewer publications, whether empirical, comparative or review, addressing this programme area. There are a number of possible reasons for this: the review period may have missed an earlier generation of publications on community caregivers and counsellors; strategies such as the “community system strengthening” framework of the Global Fund for AIDS, TB and Malaria [94] and UNAIDS’ “90-90-90” treatment targets [95] have not focused specifically on CHWs as players; HIV-treatment programmes tend to be facility based; and the HIV response also has a shorter history than the child survival interventions, which evolved into the iCCM package in an iterative process over many years and which built on a long-standing MCH focus in primary health care.

As low- and middle-income countries confront a new generation of health challenges such as non-communicable diseases, mental health and violence and injury, the repertoire of possible CHW roles is ever-expanding. There is a danger of role fragmentation and overload and a need to re-think roles in new and more complex ways. Layered approaches where roles are distributed amongst a number of cadres from expert patient to volunteer to remunerated cadres may be required [39, 91]. Similarly, strategies of specialization [41] and the balance between disease-specific and integrated approaches need to be defined. In the process, there is a risk that the social and environmental health roles of CHWs get crowded out by technical and treatment roles of core cadres, especially if the latter are incentivized [43].

The CHW programmes and interventions reported also reflected different orientations along a continuum of technical/biomedical to social/participatory and with different mixes of prevention, promotion, treatment and social mobilization. Some approached CHW roles as a set of predefined intervention packages, while in others CHW roles emerged as tailored programmes specific to local and national contexts, sometimes developed through action-learning methodologies. These differences suggest different kinds of relationship to community. They tended to follow regional and country lines indicating their different histories, programmatic traditions and discourses. This is worthy of further examination.

Similarly, the initiatives reported had varying degrees of closeness to government and the formal health system. Most LMIC health systems have experimented with and developed policy on CHWs. However, the extent to which reports (whether programme specific or comprehensive) were embedded in or reported on official, national CHW programmes varied considerably. As the number of initiatives grows, the need for national and local coordination and stewardship becomes more urgent. While some of the papers touched on these broader system questions, it is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss these.

Conclusions

The growth in literature on CHWs provides empirical evidence of increasing expectations for addressing health burdens through CHWs and community-based action. However, as Tulenko et al. point out, these developments have been heavily donor dependent, resulting in a fragmented environment where disease-specific responses dominate [8]. This raises important questions of sustainability and the need to integrate the plethora of new initiatives into coherent national programmes and local primary health care systems [35, 96].

Abbreviations

- ART:

-

Antiretroviral therapy

- BRAC:

-

Building Resources Across Communities (formerly Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee)

- CHW:

-

Community health worker

- HEW:

-

Health extension worker

- iCCM:

-

Integrated community case management

- LMIC:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- MCH:

-

Maternal-child health

- NCD:

-

Non-communicable disease

References

Campbell J, Admasu K, Soucat A, Tlou S. Maximizing the impact of community-based practitioners in the quest for universal health coverage. Bull World Health Organ. 2015;93(9):590A.

Balabanova D, Mills A, Conteh L, Akkazieva B, Banteyerga H, Dash U, et al. Good health at low cost 25 years on: lessons for the future of health systems strengthening. Lancet. 2013;381(9883):2118–33.

Lewin S, Munabi-Babigumira S, Glenton C, Daniels K, Bosch-Capblanch X, van Wyk BE, et al. Lay health workers in primary and community health care for maternal and child health and the management of infectious diseases (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(3):CD004015.

Malarcher S, Meirik O, Lebetkin E, Shah I, Spieler J, Stanback J. Provision of DMPA by community health workers: what the evidence shows. Contraception. 2011;83(6):495–503.

Mutamba BB, van Ginneken N, Paintain LS, Wandiembe S, Schellenberg D. Roles and effectiveness of lay community health workers in the prevention of mental, neurological and substance use disorders in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:412.

Perry H, Zulliger R, Rogers M. Community health workers in low-, middle-, and high-income countries: an overview of their history, recent evolution, and current effectiveness. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:399–421.

Third Global Forum on HRH. Joint commitment to harmonized partners action for community health workers and frontline health workers. Global Health Workforce Alliance: Third Global Forum on Human Resources for Health. Recife, Brazil; 2013.

Tulenko K, Mogedal S, Afzal MM, Frymus D, Oshin A, Pate M, et al. Community health workers for universal health-care coverage: from fragmentation to synergy. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:847–52.

Dahn B, Woldemariam A, Perry H, Maeda A, von Glahn D, Panjabi R, Merchant N, Vosburg K, Palazuelos D, Lu C, et al. Strengthening primary health care through community health workers: investment case and financing recommendations. Geneva: Office of UN Secretary General’s Special Envoy for Financing the Health Millennium Development Goals and for Malaria; 2015. Technical Report.

Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5:371–85.

Naimoli JF, Frymus DE, Wuliji T, Franco LM, Newsome MH. A community health worker ‘logic model’: towards a theory of enhanced performance in low- and middle-income countries. Hum Resour Health. 2014;12(1):56.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69.

Global Health Workforce Alliance. Global experience of community health workers for delivery of health related Millennium Development Goals: a systematic review, country case studies, and recommendations for integration into national health systems. Geneva: Global Health Workforce Alliance; 2010.

Earth Institute. One million community health workers: technical task force report. New York: Earth Institute, Columbia University; 2011.

Perry H, Crigler L, Hodgins S. Developing and strengthening community health worker programs at scale a reference guide and case studies for program managers and policy makers. Baltimore: Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program (MCHIP); 2014.

UNICEF, World Health Organization. WHO/UNICEF joint statement: integrated community case management an equity-focused strategy to improve access to essential treatment services for children. New York: UNICEF/WHO; 2012.

Patel V, Weiss HA, Chowdhary N, Naik S, Pednekar S, Chatterjee S, et al. Lay health worker led intervention for depressive and anxiety disorders in India: impact on clinical and disability outcomes over 12 months. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(6):459–66.

Shinde S, Andrew G, Bangash O, Cohen A, Kirkwood B, Patel V. The impact of a lay counselor led collaborative care intervention for common mental disorders in public and private primary care: a qualitative evaluation nested in the MANAS trial in Goa, India. Soc Sci Med. 2013;88:48–55.

Pagel C, Lewycka S, Colbourn T, Mwansambo C, Meguid T, Chiudzu G, et al. Estimation of potential effects of improved community-based drug provision, to augment health-facility strengthening, on maternal mortality due to post-partum haemorrhage and sepsis in sub-Saharan Africa: an equity-effectiveness model. Lancet. 2009;374(9699):1441–8.

Morrison J, Tumbahangphe KM, Budhathoki B, Neupane R, Sen A, Dahal K, et al. Community mobilisation and health management committee strengthening to increase birth attendance by trained health workers in rural Makwanpur, Nepal: study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2011;12(1):128–39.

Lassi ZS, Haider BA, Bhutta ZA. Community-based intervention packages for reducing maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality and improving neonatal outcomes (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(11):CD007754.

Waiswa P, Peterson SS, Namazzi G, Ekirapa EK, Naikoba S, Byaruhanga R, et al. The Uganda Newborn Study (UNEST): an effectiveness study on improving newborn health and survival in rural Uganda through a community-based intervention linked to health facilities—study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2012;13(1):1–16.

Rahman A, Haq Z, Sikander S, Ahmad I, Ahmad M, Hafeez A. Using cognitive-behavioural techniques to improve exclusive breastfeeding in a low-literacy disadvantaged population. Matern Child Nutr. 2012;8(1):57–71.

Kim MH, Ahmed S, Preidis GA, Abrams EJ, Hosseinipour MC, Giordano TP, et al. Low rates of mother-to-child HIV transmission in a routine programmatic setting in Lilongwe, Malawi. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e64979.

le Roux IM, Tomlinson M, Harwood JM, O’Connor MJ, Worthman CM, Mbewu N, et al. Outcomes of home visits for pregnant mothers and their infants: a cluster randomized controlled trial. AIDS. 2013;27(9):1461–71.

Sando D, Geldsetzer P, Magesa L, Lema IA, Machumi L, Mwanyika-Sando M, et al. Evaluation of a community health worker intervention and the World Health Organization’s Option B versus Option A to improve antenatal care and PMTCT outcomes in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: study protocol for a cluster-randomized controlled health systems implementation trial. Trials. 2014;15:359.

Glenton C, Scheel IB, Lewin S, Swingler GH. Can lay health workers increase the uptake of childhood immunisation? Systematic review and typology. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16(9):1044–53.

Jilcott SB, Ickes SB, Ammerman AS, Myhre JA. Iterative design, implementation and evaluation of a supplemental feeding program for underweight children ages 6–59 months in Western Uganda. Matern Child Heal J. 2010;14(2):299–306.

Kimani-Murage EW, Kyobutungi C, Ezeh AC, Wekesah F, Wanjohi M, Muriuki P, et al. Effectiveness of personalised, home-based nutritional counselling on infant feeding practices, morbidity and nutritional outcomes among infants in Nairobi slums: study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:445.

Rahman A, Iqbal Z, Roberts C, Husain N. Cluster randomized trial of a parent-based intervention to support early development of children in a low-income country. Child Care Heal Dev. 2009;35(1):56–62.

Yousafzai AK, Rasheed MA, Rizvi A, Armstrong R, Bhutta ZA. Effect of integrated responsive stimulation and nutrition interventions in the Lady Health Worker programme in Pakistan on child development, growth, and health outcomes: a cluster-randomised factorial effectiveness trial. Lancet. 2014;384(9950):1282–93.

Marsh DR, Gilroy KE, Van de Weerdt R, Wansi E, Qazi S. Community case management of pneumonia: at a tipping point? Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(5):381–9.

Christopher JB, Le MA, Lewin S, Ross DA. Thirty years after Alma-Ata: a systematic review of the impact of community health workers delivering curative interventions against malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoea on child mortality and morbidity in sub-Saharan Africa. Hum Resour Health. 2011;9:27.

Amouzou A, Morris S, Moulton LH, Mukanga D. Assessing the impact of integrated community case management (iCCM) programs on child mortality: review of early results and lessons learned in sub-Saharan Africa. J Glob Health. 2014;4:2.

Bennett S, George A, Rodriguez D, Shearer J, Diallo B, Konate M, et al. Policy challenges facing integrated community case management in Sub‐Saharan Africa. Trop Med Int Heal. 2014;19(7):872–82.

Prost A, Colbourn T, Seward N, Azad K, Coomarasamy A, Copas A, et al. Women’s groups practising participatory learning and action to improve maternal and newborn health in low-resource settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;381(9879):1736–46.

Aghajanian A, Mehryar AH, Ahmadnia S, Kazemipour S. Impact of rural health development programme in the Islamic Republic of Iran on rural-urban disparities in health indicators. East Mediterr Heal J. 2007;13(6):1466–75.

Giugliani C, Harzheim E, Duncan MS, Duncan BB. Effectiveness of community health workers in Brazil: a systematic review. J Ambul Care Manage. 2011;34(4):326–38.

Banteyerga H. Ethiopia’s health extension program: improving health through community involvement. MEDICC Rev. 2011;13(3):46–9.

El Arifeen S, Christou A, Reichenbach L, Osman FA, Azad K, Islam KS, et al. Community-based approaches and partnerships: innovations in health-service delivery in Bangladesh. Lancet. 2013;382(9909):2012–26.

Smith S, Deveridge A, Berman J, Negin J, Mwambene N, Chingaipe E, et al. Task-shifting and prioritization: a situational analysis examining the role and experiences of community health workers in Malawi. Hum Resour Health. 2014;12:24.

Jaskiewicz W, Tulenko K. Increasing community health worker productivity and effectiveness: a review of the influence of the work environment. Hum Resour Health. 2012;10(1):38.

Sundararaman T, Ved R, Gupta G, Samatha M. Determinants of functionality and effectiveness of community health workers: results from evaluation of ASHA program in eight Indian states. BMC Proc. 2012;6 Suppl 5:O30.

Celletti F, Wright A, Palen J, Frehywot S, Markus A, Greenberg A, et al. Can the deployment of community health workers for the delivery of HIV services represent an effective and sustainable response to health workforce shortages? Results of a multicountry study. AIDS. 2010;24 Suppl 1:S45–57.

Datiko DG, Lindtjorn B. Health extension workers improve tuberculosis case detection and treatment success in southern Ethiopia: a community randomized trial. PLoS One. 2009;4(5):e5443.

Clarke M, Dick J, Zwarenstein M, Lombard CJ, Diwan VK. Lay health worker intervention with choice of DOT superior to standard TB care for farm dwellers in South Africa: a cluster randomised control trial. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9(6):673–9.

Hermann K, Van Damme W, Pariyo GW, Schouten E, Assefa Y, Cirera A, et al. Community health workers for ART in sub-Saharan Africa: learning from experience—capitalizing on new opportunities. Hum Resour Health. 2009;7(31):1–11.

Decroo T, Rasschaert F, Telfer B, Remartinez D, Laga M, Ford N. Community-based antiretroviral therapy programs can overcome barriers to retention of patients and decongest health services in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Int Heal. 2013;5(3):169–79.

Atkins S, Lewin S, Jordaan E, Thorson A. Lay health worker-supported tuberculosis treatment adherence in South Africa: an interrupted time series study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15(1):84–9.

Mwai GW, Mburu G, Torpey K, Frost P, Ford N, Seeley J. Role and outcomes of community health workers in HIV care in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18586.

Uwimana J, Zarowsky C, Hausler H, Jackson D. Training community care workers to provide comprehensive TB/HIV/PMTCT integrated care in KwaZulu-Natal: lessons learnt. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17(4):488–96.

Aantjes C, Quinlan T, Bunders J. Integration of community home based care programmes within national primary health care revitalisation strategies in Ethiopia, Malawi, South-Africa and Zambia: a comparative assessment. Glob Heal. 2014;10(85):42–68.

Maes K, Kalofonos I. Becoming and remaining community health workers: perspectives from Ethiopia and Mozambique. Soc Sci Med. 2013;87:52–9.

Okwundu C, Nagpal S, Musekiwa A, Sinclair D. Home- or community-based programmes for treating malaria (review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(5).

Msyamboza KP, Savage EJ, Kazembe PN, Gies S, Kalanda G, D’Alessandro U, et al. Community-based distribution of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine for intermittent preventive treatment of malaria during pregnancy improved coverage but reduced antenatal attendance in southern Malawi. Trop Med Int Heal. 2009;14(2):183–9.

Bojang KA, Akor F, Conteh L, Webb E, Bittaye O, Conway DJ, et al. Two strategies for the delivery of IPTc in an area of seasonal malaria transmission in the Gambia: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2011;8(2):e1000409.

Tine RCK, Ndour CT, Faye B, Cairns M, Sylla K, Ndiaye M, et al. Feasibility, safety and effectiveness of combining home based malaria management and seasonal malaria chemoprevention in children less than 10 years in Senegal: a cluster-randomised trial. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2014;108(1):13–21.

Das A, Friedman J, Kandpal E, Ramana GN V, Gupta RK D, Pradhan MM, et al. Strengthening malaria service delivery through supportive supervision and community mobilization in an endemic Indian setting: an evaluation of nested delivery models. Malar J England. 2014;13:482.

Prata N, Weidert K, Fraser A, Gessessew A. Meeting rural demand: a case for combining community-based distribution and social marketing of injectable contraceptives in Tigray, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e68794.

Asnake M, Henry EG, Tilahun Y, Oliveras E. Addressing unmet need for long-acting family planning in Ethiopia: uptake of single-rod progestogen contraceptive implants (Implanon) and characteristics of users. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;123 Suppl 1:e29–32.

Holanda Jr F, Castelo A, Veras TMCW, de Almeida FML, Lins MZ, Dores GB. Primary screening for cervical cancer through self sampling. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;95(2):179–84.

Hyoju SK, Agrawal CS, Pokhrel PK, Agrawal S. Transfer of clinical breast examination skills to female community health volunteers in Nepal. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev. 2011;12(12):3353–6.

Wadler BM, Judge CM, Prout M, Allen JD, Geller AC. Improving breast cancer control via the use of community health workers in South Africa: a critical review. J Oncol. 2011;2011:150423.

Katabarwa M, Habomugisha P, Eyamba A, Agunyo S, Mentou C. Monitoring ivermectin distributors involved in integrated health care services through community-directed interventions—a comparison of Cameroon and Uganda experiences over a period of three years (2004–2006). Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(2):216–23.

Omedo MO, Matey EJ, Awiti A, Ogutu M, Alaii J, Karanja DM, et al. Community health workers’ experiences and perspectives on mass drug administration for schistosomiasis control in western Kenya: the SCORE Project. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87(6):1065–72.

Jenson A, Gracewello C, Mkocha H, Roter D, Munoz B, West S. Gender and performance of community treatment assistants in Tanzania. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2014;26(5):524–9.

Vouking MZ, Tamo VC, Mbuagbaw L. The impact of community health workers (CHWs) on Buruli ulcer in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;15:19.

Das VNR, Pandey RN, Pandey K, Singh V, Kumar V, Matlashewski G, et al. Impact of ASHA training on active case detection of visceral leishmaniasis in Bihar. India PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(5):1–5.

Winangnon S, Sriamporn S, Senarak W, Saranrittichai K, Vatanasapt P, Moore MA. Use of lay health workers in a community-based chronic disease control program. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2007;8(3):457–61.

Balagopal P, Kamalamma N, Patel TG, Misra R. A community-based participatory diabetes prevention and management intervention in rural India using community health workers. Diabetes Educ. 2012;38(6):822–34.

Nishtar S, Badar A, Kamal MU, Iqbal A, Bajwa R, Shah T, et al. The Heartfile Lodhran CVD prevention project—end of project evaluation. Promot Educ. 2007;14(1):17–27.

Bittencourt L, Scarinci IC. Is there a role for community health workers in tobacco cessation programs? Perceptions of administrators and health care professionals. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(5):626–31.

Abanilla PKA, Huang K-Y, Shinners D, Levy A, Ayernor K, Aikins A de-G, et al. Cardiovascular disease prevention in Ghana: feasibility of a faith-based organizational approach. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89(9):648–56.

Vedanthan R, Kamano JH, Naanyu V, Delong AK, Were MC, Finkelstein EA, et al. Optimizing linkage and retention to hypertension care in rural Kenya (LARK hypertension study): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15(1):1–21.

Tsolekile LP, Puoane T, Schneider H, Levitt NS, Steyn K, Africa S, et al. The roles of community health workers in management of non-communicable diseases in an urban township. Afr J Prm Heal Care Fam Med. 2014;6(1):1–8.

Farzadfar F, Murray CJL, Gakidou E, Bossert T, Namdaritabar H, Alikhani S, et al. Effectiveness of diabetes and hypertension management by rural primary health-care workers (Behvarz workers) in Iran: a nationally representative observational study. Lancet. 2012;379(9810):47–54.

Cabral NL, Franco S, Longo A, Moro C, Buss TA, Collares D, et al. The Brazilian Family Health Program and secondary stroke and myocardial infarction prevention: a 6-year cohort study. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(12):e90–5.

Jafar TH, Islam M, Hatcher J, Hashmi S, Bux R, Khan A, et al. Community based lifestyle intervention for blood pressure reduction in children and young adults in developing country: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340(c2641):1–7.

Menon J, Joseph J, Thachil A, Attacheril TV, Banerjee A. Surveillance of noncommunicable diseases by community health workers in Kerala. Glob Heart. 2014;9(4):409–17.

Rahman A, Malik A, Sikander S, Roberts C, Creed F. Cognitive behaviour therapy-based intervention by community health workers for mothers with depression and their infants in rural Pakistan: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9642):902–9.

Kauye F, Chiwandira C, Wright J, Common S, Phiri M, Mafuta C, et al. Increasing the capacity of health surveillance assistants in community mental health care in a developing country, Malawi. Malawi Med J Malawi. 2011;23(3):85–8.

Jenkins R, Kiima D, Okonji M, Njenga F, Kingora J, Lock S. Integration of mental health into primary care and community health working in Kenya: context, rationale, coverage and sustainability. Ment Health Fam Med. 2010;7(1):37–47.

Ramos-Cerqueira ATA, Torres AR, Crepaldi AL, Oliveira NIL, Scazufca M, Menezes PR, et al. Identification of dementia cases in the community: a Brazilian experience. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(10):1738–42.

Nogueira EL, Rubin LL, Giacobbo S de S, Gomes I, Neto AC. Screening for depressive symptoms in older adults in the Family Health Strategy, Porto Alegre, Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 2014;48(3):368–77.

Dias A, Dewey ME, D’Souza J, Dhume R, Motghare DD, Shaji KS, et al. The effectiveness of a home care program for supporting caregivers of persons with dementia in developing countries: a randomised controlled trial from Goa, India. PLoS One. 2008;3(6):e2333.

Chatterjee S, Naik S, John S, Dabholkar H, Balaji M, Koschorke M, et al. Effectiveness of a community-based intervention for people with schizophrenia and their caregivers in India (COPSI): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9926):1385–94.

Haines A, Sanders D, Lehmann U, Rowe AK, Lawn JE, Jan S, et al. Achieving child survival goals: potential contribution of community health workers. Lancet. 2007;369(9579):2121–31.

Prata N, Gessessew A, Cartwright A, Fraser A. Provision of injectable contraceptives in Ethiopia through community-based reproductive health agents. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89(8):556–64.

Rasschaert F, Philips M, Van Leemput L, Assefa Y, Schouten E, Van Damme W. Tackling health workforce shortages in antiretroviral treatment scale-up—experiences from Ethiopia and Malawi. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57(2):109–12.

Yitayal M, Berhane Y, Worku A, Kebede Y. Health extension program factors, frequency of household visits and being model households, improved utilization of basic health services in Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:156.

Standing H, Chowdhury AMR. Producing effective knowledge agents in a pluralistic environment: what future for community health workers? Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(10):2096–107.

Dalglish SL, George A, Shearer JC, Bennett S. Epistemic communities in global health and the development of child survival policy: a case study of iCCM. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30(2):ii12–25.

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Financing global health 2014: shifts in funding as the MDG era closes. Seattle: IHME; 2015.

The Global Fund. Community systems strengthening framework. 2014.

UNAIDS. 90-90-90—an ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2014.

Sarriot E, Morrow M, Langston A, Weiss J, Landegger J, Tsuma L, et al. A causal loop analysis of the sustainability of integrated community case management in Rwanda. Soc Sci Med. 2015;131(2015):147–55.

Mangham-Jefferies L, Mathewos B, Russell J, Bekele A. How do health extension workers in Ethiopia allocate their time? Hum Resour Health. 2014;12:61.

Kok MC, Muula AS. Motivation and job satisfaction of health surveillance assistants in Mwanza, Malawi: an explorative study. Malawi Med J. 2013;25(1):5–11.

Javanparast S, Baum F, Labonte R, Sanders D, Heidari G, Rezaie S. A policy review of the community health worker programme in Iran. J Public Health Policy. 2011;32(2):263–76.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The scoping review was supported by the SAMRC/UWC Health Services to Systems Unit.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

HS led the review. DO conducted the literature search and DO and HS screened the abstracts and coded the entries. HS conducted the analysis and drafted the article. UL provided advice at all stages. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Coding of papers by theme. (DOCX 16 kb)

Additional file 2: Figure S1.

Distribution of publications by region and country. (DOCX 15 kb)

Additional file 3: Table S2.

Distribution of publications by region, country and programmatic focus. (DOCX 77 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Schneider, H., Okello, D. & Lehmann, U. The global pendulum swing towards community health workers in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review of trends, geographical distribution and programmatic orientations, 2005 to 2014. Hum Resour Health 14, 65 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-016-0163-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-016-0163-2